Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

G.R. No. 174173 March 7, 2012 MA. MELISSA A. GALANG, Petitioner, JULIA MALASUGUI, Respondent

Transféré par

Joseph Santos GacayanDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

G.R. No. 174173 March 7, 2012 MA. MELISSA A. GALANG, Petitioner, JULIA MALASUGUI, Respondent

Transféré par

Joseph Santos GacayanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

G.R. No.

174173

March 7, 2012

MA. MELISSA A. GALANG, Petitioner, vs. JULIA MALASUGUI, Respondent. DECISION PEREZ, J.: Before the Court is a Petition for Review on Certiorari1 of the Decision2 of the Twenty First Division of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA G.R. SP No. 62700 dated 18 April 2006, granting the Special Civil Action for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the 1997 Revised Rules of Civil Procedure filed by Julia Malasugui and reversing the Resolution of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) Fifth Division. The dispositive portion of the assailed decision reads: WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant petition is GRANTED. The RESOLUTION dated June 29, 2000 of public respondent National Labor Relations Commission (Fifth Division) is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. Private respondent Liza Galang is hereby ORDERED to pay petitioner Julia Malasugui the following: salary differential in the amount of P19,554.23; 13th month pay differential in the amount of P4,620.50; separation pay equivalent to one month salary for every year of continuous service; and full backwages from the time of her illegal dismissal up to the date of finality of this judgment. 3 Respondent has this story: On 26 June 1993, Julia Malasugui (Malasugui) was hired by Ma. Melissa A. Galang (Galang) to take care, oversee and man the premises of the Davao Royal Garden Compound (Pangi Property) the main compound of Galang where the orchids and other ornamental plants used for the business were nursed and propagated. Aside from taking care of the plants, she was required by Galang to be present at the premises at seven thirty in the morning until five thirty in the afternoon every day, including Saturdays, Sundays and Holidays without any day-offs.4 Galang would visit the premises at least thrice a week and give her instructions on what to do and what were the things to be prioritized. Among these instructions were tending, watering and spraying with chemicals various orchid varieties, packing the orchids for export purposes and cleaning the surroundings of the half-hectare premises.5 From 1993-1995, Malasugui was paid by Galang P40.00 as daily wage and after three years, it was increased toP70.00 per day until February 1999.6 She was also given one thousand pesos (P1,000.00) bonus every December by Galang.7 Malasugui was later made to stay and live at the premises, particularly in one of the bunk houses within the Pangi property which was vacated by the family driver of Galang, so that she could watch and guard the premises even during nighttime. 8 However, she had to buy her food.9 In November 1998, she became sick with severe cough and asked for financial assistance from Galang for medical check-up. The coughing became incessant which prompted Galang to bring her to a doctor and made to undergo a series of examinations including chest radiographic examination. Thereafter, she was terminated from work and barred from entering the Pangi property on 27 January 1999.10 The allegations of respondent were corroborated by the neighbors of the Pangi property, namely: Nestor Siarot (Siarot) and Ledwina M. Mendoza (Mendoza). Siarot in his affidavit attested that he was an employee of PG Lumber, the office of which is adjacent to the Pangi property. He attested that he knows that Malasugui slept within the premises and tended to the plants and orchids, either by watering, cultivating or spraying the same with chemicals; and that Galang is the owner of the Davao Royal Garden and Malasugui received instructions from her.11

Mendoza, in turn, confirmed Siarots statement. She said that she personally knows that Malasugui was an employee of Davao Royal Garden, a business establishment engaged in the business of growing of orchids and that in the course of her employment Malasugui was made to stay inside the premises of the Pangi property.12 On the other hand is the version of the defense: Petitioner Galang narrated that she is the owner of Davao Royal Garden, a sole proprietorship engaged in the retailing of ornamental plants, consisting of receiving of cut-flowers from farmers or suppliers, packing them for shipment, and shipping them to the buyers.13 However, Galang did not hire respondent Malasugui. Her mother Elsa Galang (Elsa) is an orchid hobbyist who is engaged in the propagation of orchid plants and occasionally sells them to her friends and acquaintances.14 In 1993, her family bought a parcel of land at Matini, Pangi, Davao City (Pangi property) on which they intended to construct their family home. While construction was yet to start, Elsa transferred her orchid collection to the Pangi property. There thus was a need to oversee the property and Elsa decided to allow their laundrywoman Aurora Solis (Solis) to stay in one of the bunk houses within the property to take care of the orchid collection. At the same time, Solis would also assist Galang in her business. The other bunkhouse was then occupied by their family driver.15 Sometime in 1995, Malasugui visited Solis, a relative by affinity, in the Pangi property. She told Solis of her intention to find a job in the city but she had no place to stay in the meantime. Malasugui could not be hired by the Galang. There was no need for another employee since Solis was already taking care of Elsas orchid collection and Galangs orchid business. However, Malasugui was allowed to stay in the bunkhouse occupied by Solis.16 When the family driver left the other bunkhouse, Malasugui occupied it and brought along her family as well. The Galang family tolerated this arrangement for around six years as an act of kindness. During these times, Malasugui did not look for any job as initially intended. They did not require Malasugui to pay for rentals, electricity, water and other utilities.17 Solis, on the other hand, asked Malasugui to help out in her tasks of weeding, watering, spraying chemicals on the orchids as well as cleaning the Pangi property. When Galang inquired why Malasugui was doing such tasks, Solis replied that she asked Malasugui to assist her since she and her family were occupying the property. The assistance rendered by Malasugui was in gratitude for the hospitality of the Galang family.18 Admittedly, Galang occasionally gave money to Malasugui out of charity. She even answered for the medical expenses of Malasugui when the latter became sick of excessive coughing early in 1999. She even made an arrangement with a radiologist for her diagnostic examination but Malasugui did not show up at the appointed time. When confronted by Galang about this, Malasugui packed her belongings and left the Pangi property. She was not asked nor forced to leave the premises by any member of the Galang family.19 Malasugui filed a complaint for illegal dismissal before the National Labor Relations Commission, Regional Arbitration Branch No. XI of Davao City on 8 February 1999 claiming underpayment of wages, holiday pay, separation pay and 13th month differential.20 On 28 September 1999, Labor Arbiter Antonio M. Villanueva rendered judgment21 finding complainants charge of illegal dismissal without merit. The dispositive portion reads: WHEREFORE, in consideration of all the foregoing, judgment is hereby rendered finding complainants charge of illegal dismissal without merit but ordering respondents Davao Royal Garden and Melissa Galang to pay jointly and severally the sum of TWENTY FOUR THOUSAND ONE HUNDRED SEVENTY FOUR PESOS AND SEVENTY THREE CENTAVOS (P24,174.73) to complainant as wage differential and 13th month pay differential. Ordering the dismissal of the claims for holiday pay and separation pay for lack of merit. 22

The Labor Arbiter found that Malasugui was hired to work for Galang in relation to her orchid business. Her tasks of assisting Solis in watering, weeding and cleaning the surroundings led the Labor Arbiter to conclude that with the knowledge and acquiescence of Melissa Galang, Malasugui was made "to suffer or permit to work" within the definition of employee under Article 97(e) of the Labor Code. However, the Labor Arbiter ruled that there was no substantial evidence that Malasugui was illegally dismissed and barred from entering the property after she, without any notice to her employer, packed her belongings and left the Pangi property. Respondent was awarded salary differential and 13th month pay but was denied holiday pay. Galang appealed before the NLRC assailing the finding of the Labor Arbiter that there was an employer-employee relationship between her and Malasugui. On 29 June 2000, the NLRC affirmed with modification the Decision of the Labor Arbiter. The dispositive portion of the resolution reads: WHEREFORE, premises laid, the decision appealed from is hereby MODIFIED by deleting the award of salary differentials. The rest of the Labor Arbiters decision stands.23 The NLRC in its Resolution24 deleted the award of salary differentials on the reason that even though the salary received by the complainant was below that provided by law by Ten Pesos (P10.00) per day, the non-monetary benefits received by her such as lodging, free water, electricity and telephone, if quantified, will be more than enough to compensate the difference. To do otherwise would result in unjust enrichment on the part of Malasugui to the detriment of Galang. The Motion for Reconsideration25 filed by Malasugui was denied by the NLRC in a Resolution dated 29 September 2000. Aggrieved, Malasugui filed a Special Civil Action for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the Revised Rules of Civil Procedure before the CA alleging grave abuse of discretion on the part of NLRC.26 The CA granted the petition filed by Malasugui. It ruled that respondent was illegally dismissed by Galang. It reinstated the award of salary differential to Malasugui in addition to the 13th month pay. Further, because of the ruling of illegal dismissal against Galang, the appellate court awarded separation pay to Malasugui for every year of continuous service and full backwages from the time of her dismissal up to the time of the finality of the judgment. The following are the assignment of errors presented before this Court: THE COURT A QUO ERRED IN DECIDING QUESTIONS OF SUBSTANCE CONTRARY TO LAW AND SETTLED RULINGS OF THE SUPREME COURT IN THE FOLLOWING: A. THE RESPONDENT [MALASUGUI] WAS ILLEGALLY AND CONSTRUCTIVELY DISMISSED FROM EMPLOYMENT DESPITE ABSENCE OF AN EMPLOYER-EMPLOYEE RELATIONSHIP AND THEREFORE ENTITLED TO SEPARATION PAY AND BACKWAGES. B. THE CONCLUSIONS REACHED BY THE COURT OF APPEALS ARE CONTRARY TO THOSE OF THE LABOR ARBITER AND NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION AND ARE MERE CONCLUSIONS PREMISED ON ERRONEOUS ASSUMPTIONS OF FACTS NOT BORNE OUT OF THE RECORD.27 The basic issues are, first, whether or not Malasugui is an employee of Galang; and second if she is an employee, whether or not Malasugui was constructively dismissed. All three, Labor Arbiter, the NLRC and the CA ruled that there was an employer-employee relationship between Galang and Malasugui. We do not see any reason to rule otherwise. This Court is not a trier of facts and does not routinely undertake the reexamination of the evidence presented by the contending parties for the factual findings of the labor officials who have acquired expertise in their own fields are accorded respect and even finality if affirmed on appeal to the Court of Appeals. 28

Such principle cannot, however, apply to the finding of illegal dismissal against Galang. The Labor Arbiter and the NLRC both ruled that there was no illegal dismissal, but the Court of Appeals reversed such findings. We find a need to look into the decision of the CA. When supported by substantial evidence, the findings of fact of the CA are conclusive and binding on the parties and are not reviewable by this Court, unless the case falls under any of the following recognized exceptions: (1) When the conclusion is a finding grounded entirely on speculation, surmises and conjectures; (2) When the inference made is manifestly mistaken, absurd or impossible; (3) Where there is a grave abuse of discretion; (4) When the judgment is based on a misapprehension of facts; (5) When the findings of fact are conflicting; (6) When the Court of Appeals, in making its findings, went beyond the issues of the case and the same is contrary to the admissions of both appellant and appellee; (7) When the findings are contrary to those of the trial court [in this case the administrative bodies of Labor Arbiter and NLRC]; (8) When the findings of fact are conclusions without citation of specific evidence on which they are based; (9) When the facts set forth in the petition as well as in the petitioners' main and reply briefs are not disputed by the respondents; and (10) When the findings of fact of the Court of Appeals are premised on the supposed absence of evidence and contradicted by the evidence on record. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)29 That said and done, we conclude that there was indeed an illegal dismissal of the respondent by the petitioner. We proceed from the premises that (1) as found by the labor arbiter, the NLRC and the CA, there is an employer-employee relationship between petitioner and respondent; and (2) it is a fact that there was a severance of employment. The dispute is on the reason for the severance. Petitioner pleads that there was abandonment. Respondent, as she had charged petitioner at the outset, submits that there was illegal dismissal. Jurisprudence provides that the burden of proof to show that the dismissal was for a just cause is on the employer. Petitioner alleged that respondent packed her bags and left the property after being scolded due to her non-appearance at the medical examination arranged by the petitioner. The submission is that respondent left the premises and abandoned her work. Abandonment is a form of neglect of duty, one of the just causes for an employer to terminate an employee. It is a hornbook precept that in illegal dismissal cases, the employer bears the burden of proof. For a valid termination of employment on the ground of abandonment, the employer must prove, by substantial evidence, the concurrence of the employees failure to report for work for no valid reason and his categorical intention to discontinue employment.30 There is in this case no substantial evidence that will prove respondents categorical intention to discontinue employment. On the contrary, the story of abandonment is simply doubtful. The Court of Appeals was correct in ruling that:

xxxx It is not in accord with normal human experience and too flimsy a reason for petitioner so circumstanced, to just pack up her things and vacate the Pangi property after being queried on why she did not show up at the appointed time with the radiologist. The allegation that private respondent was displeased after incurring expenses for petitioners medical check-up remained unrebutted. Hence, petitioners testimony that she was prevented entry into the Pangi property appeared more credible. xxxx31 Respondent has been in the employ of petitioner for six years when the alleged abandonment happened. Being scolded, if it were true, is hardly a reason for a gardener of six years to just pack up and leave the work premises where she was even allowed to reside, at a time when she was ill and needed medical attention. Indeed, the alleged scolding is itself incredible. The given reason was that respondent failed to show up at her arranged appointment with the radiologist. It is hard to believe that a sick gardener, certainly of minimal means, would refuse the offer of medical services. In fact, the basic allegation in respondents complaint for illegal dismissal was that petitioners "treatment to her became sour especially when she requested that she be examined by a doctor for her cough."32 And, completely belying the petitioners assertion that respondent failed to show up at the appointed time with the radiologist are two certificates issued by Radiologist Susan R. Gaspar stating that on 30 January 1999 and on 1 February 1999 respondent had her chest x-ray taken at the Radiology Section of the Polyclinic Davao.33 In the case of Garcia v. NLRC correctly relied upon by the Court of Appeals, we emphasized that there must be aconcurrence of the intention to abandon and some overt acts from which an employee may be deduced as having no more intention to work.34 Such intent to discontinue the employment must be shown by clear proof that it was deliberate and unjustified.35 In the instant case, the overt act relied upon by petitioner is not only a doubtful occurrence but is, if it did transpire, even consistent with the dismissal from employment posited by the respondent. The factual appraisal of the Court of Appeals is correct. Petitioner was displeased after incurring expenses for respondents medical check-up and, it is credible that, thereafter, respondent was prevented entry into the work premises. This is tantamount to constructive dismissal. 36 Constructive dismissal exists where there is cessation of work because continued employment is rendered impossible, unreasonable or unlikely, as an offer involving a demotion in rank and a diminution in pay. 37Constructive dismissal is a dismissal in disguise or an act amounting to dismissal but made to appear as if it were not.38 In constructive dismissal cases, the employer is, concededly, charged with the burden of proving that its conduct and action or the transfer of an employee are for valid and legitimate grounds such as genuine business necessity.391wphi1 We agree with the Court of Appeals that the incredibility of petitioners submission about abandonment of work renders credible the position of respondent that she was prevented from entering the property. This was even corroborated by the affidavits of Siarot and Mendoza which were made part of the records of this case. The dismissal of respondent places upon petitioner the burden of proof of legality of dismissal. In AMA Computer College-East Rizal v. Ignacio40 as reiterated in Gurango v. Best Chemicals and Plastics, Inc.,41the Court ruled that: In termination cases, the burden of proof rests on the employer to show that the dismissal is for just cause. When there is no showing of a clear, valid and legal cause for the termination of employment, the law considers the matter a case of illegal dismissal and the burden is on the employer to prove that the termination was for a valid or authorized cause. And the quantum of proof which the employer must discharge is substantial evidence. An employees dismissal due to serious misconduct must be supported by substantial evidence. Substantial evidence is that amount of relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion, even if other minds, equally reasonable, might conceivably opine otherwise.421wphi1 In this case, petitioner, instead of proving the legality of dismissal, relied entirely on the defense of abandonment. When such defense fell and failed, illegal dismissal was left undisputed.

Having disposed of the basic issues and found that there is an employee-employer relationship between the parties and that respondent was illegally dismissed, the rest of the disposition of the Court of Appeals will have to be, consequently, affirmed. WHEREFORE, the appeal is DENIED. The 18 April 2006 Decision of the Court of Appeals in CA G.R. SP No. 62700 is hereby AFFIRMED in toto. No cost. SO ORDERED. JOSE PORTUGAL PEREZ Associate Justice G.R. No. 171630 August 8, 2010

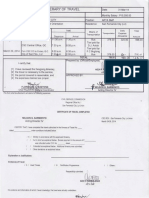

CENTURY CANNING CORPORATION, RICARDO T. PO, JR. and AMANCIO C. RONQUILLO, Petitioners, vs. VICENTE RANDY R. RAMIL, Respondent. DECISION PERALTA, J.: Before this Court is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court seeking to set aside the Decision1 and Resolution2 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP. No. 86939, dated December 1, 2005 and February 17, 2006, respectively. The antecedents are as follows: Petitioner Century Canning Corporation, a company engaged in canned food manufacturing, employed respondent Vicente Randy Ramil in August 1993 as technical specialist. Prior to his dismissal on May 20, 1999, his job included, among others, the preparation of the purchase requisition (PR) forms and capital expenditure (CAPEX) forms, as well as the coordination with the purchasing department regarding technical inquiries on needed products and services of petitioner's different departments. On March 3, 1999, respondent prepared a CAPEX form for external fax modems and terminal server, per order of Technical Operations Manager Jaime Garcia, Jr. and endorsed it to Marivic Villanueva, Secretary of Executive Vice-President Ricardo T. Po, for the latter's signature. The CAPEX form, however, did not have the complete details3 and some required signatures.4 The following day, March 4, 1999, with the form apparently signed by Po, respondent transmitted it to Purchasing Officer Lorena Paz in Taguig Main Office. Paz processed the paper and found that some details in the CAPEX form were left blank. She also doubted the genuineness of the signature of Po, as appearing in the form. Paz then transmitted the CAPEX form to Purchasing Manager Virgie Garcia and informed her of the questionable signature of Po. Consequently, the request for the equipment was put on hold due to Po's forged signature. However, due to the urgency of purchasing badly needed equipment, respondent was ordered to make another CAPEX form, which was immediately transmitted to the Purchasing Department. Suspecting him to have committed forgery, respondent was asked to explain in writing the events surrounding the incident. He vehemently denied any participation in the alleged forgery. Respondent was, thereafter, suspended on April 21, 1999. Subsequently, he received a Notice of Termination from Armando C. Ronquillo, on May 20, 1999, for loss of trust and confidence. Due to the foregoing, respondent, on May 24, 1999, filed a Complaint for illegal dismissal, non-payment of overtime pay, separation pay, moral and exemplary damages and attorney's fees against petitioner and its officers before the Labor Arbiter (LA), and was docketed as NLRC-NCR Case No. 00-05-05894-99.5 LA Potenciano S. Canizares rendered a Decision6 dated December 6, 1999 dismissing the complaint for lack of merit. Aggrieved by the LA's finding, respondent appealed to the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC). Upon recommendation of LA

Cristeta D. Tamayo, who reviewed the case, the NLRC First Division, in its Decision7dated August 26, 2002, set aside the ruling of LA Canizares. The NLRC declared respondent's dismissal to be illegal and directed petitioner to reinstate respondent with full backwages and seniority rights and privileges. It found that petitioner failed to show clear and convincing evidence that respondent was responsible for the forgery of the signature of Po in the CAPEX form. Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration. To respondent's surprise and dismay, the NLRC reversed itself and rendered a new Decision8 dated October 20, 2003, upholding LA Canizares' dismissal of his complaint. Respondent filed a motion for reconsideration, which was denied by the NLRC. Frustrated by this turn of events, respondent filed a petition for certiorari with the CA. The CA, in its Decision dated December 1, 2005, rendered judgment in favor of respondent and reinstated the earlier decision of the NLRC, dated August 26, 2002. It ordered petitioner to reinstate respondent, without loss of seniority rights and privileges, and to pay respondent full backwages from the time his employment was terminated on May 20, 1999 up to the time of the finality of its decision. The CA, likewise, remanded the case to the LA for the computation of backwages of the respondent. Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration, which the CA denied in a Resolution dated February 17, 2006. Hence, the instant petition assigning the following errors: I THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED IN DISREGARDING THE UNANIMOUS FINDINGS OF THE LABOR ARBITER AND THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION SUSTAINING THE LEGALITY OF PRIVATE RESPONDENT'S TERMINATION FROM HIS EMPLOYMENT. II THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED IN NOT HOLDING THAT PETITIONER CORPORATION FAILED TO SATISFY THE BURDEN OF PROVING THAT THE DISMISSAL OF PRIVATE RESPONDENT WAS FOR A VALID OR AUTHORIZED CAUSE. III THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS SERIOUSLY ERRED IN HOLDING THAT FOR LOSS OF TRUST AND CONFIDENCE TO BE A VALID GROUND FOR AN EMPLOYEE'S DISMISSAL, IT MUST BE SUBSTANTIAL AND NOT ARBITRARY, AND MUST BE FOUNDED ON CLEARLY ESTABLISHED FACTS, OVERLOOKING THE RULE THAT THE MERE EXISTENCE OF A BASIS FOR BELIEVING THAT SUCH EMPLOYEE HAS BREACHED THE TRUST AND CONFIDENCE OF HIS EMPLOYER SUFFICES FOR HIS DISMISSAL. IV THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED IN NOT HOLDING THAT ASIDE FROM HIS INVOLVEMENT IN THE FORGERY OF THE CAPITAL EXPENDITURE (CAPEX) FORMS, PRIVATE RESPONDENT'S PAST VIOLATIONS OR ADMITTED INFRACTIONS OF COMPANY RULES AND REGULATIONS ARE MORE THAN SUFFICIENT GROUNDS TO JUSTIFY THE TERMINATION OF HIS EMPLOYMENT WITH PETITIONER CORPORATION. Petitioner's main allegation is that there are factual and legal grounds constituting substantial proof that respondent was clearly involved in the forgery of the CAPEX form, i.e., respondent is the forger of the signature of Po, as he is the custodian and the one who prepared the CAPEX form; the forged signature was already existing when he submitted the same for processing; he has the motive to forge the signature; respondent has the propensity to deviate from the Standard Operating Procedure as shown by the fact that the CAPEX form, with the forged signature of Po, is not complete in details and lacks the required signatures; also, in February 1999, respondent ordered 8 units of External Fax Modem without the required CAPEX form and a PR form.

Petitioner insists that the mere existence of a basis for believing that respondent employee has breached the trust and confidence of his employer suffices for his dismissal. Finally, petitioner maintains that aside from respondent's involvement in the forgery of the CAPEX form, his past violations of company rules and regulations are more than sufficient grounds to justify his termination from employment. In his Comment, respondent alleged that petitioner failed to present clear and convincing evidence to prove his participation in the charge of forgery nor any damage to the petitioner. Anent the first issue raised, petitioner faults the CA in disregarding the unanimous findings of the LA and the NLRC sustaining the legality of respondent's termination from his employment. The rule is that high respect is accorded to the findings of fact of quasi-judicial agencies, more so in the case at bar where both the LA and the NLRC share the same findings. The rule is not, however, without exceptions one of which is when the findings of fact of the labor officials on which the conclusion was based are not supported by substantial evidence. The same holds true when it is perceived that far too much is concluded, inferred or deduced from bare facts adduced in evidence.9 In the case at bar, the NLRC's findings of fact upon which its conclusion was based are not supported by substantial evidence, that is, the amount of relevant evidence, which a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to justify a conclusion. 10 As correctly found by the CA: x x x The record of the case is bereft of evidence that would clearly establish Ramil's involvement in the forgery. They did not even submit any affidavit of witness11 or present any during the hearing to substantiate their claim against Ramil.12 Respondent alleged in his position paper that after preparing the CAPEX form on March 3, 1999, he endorsed it to Marivic Villanueva for the signature of the Executive Vice-President Ricardo T. Po. The next day, March 4, 1999, respondent received the CAPEX form containing the signature of Po. Petitioner never controverted these allegations in the proceedings before the NLRC and the CA despite its opportunity to do so. Petitioner's belated allegations in its reply filed before this Court that Marivic Villanueva denied having seen the CAPEX form cannot be given credit. Points of law, theories, issues and arguments not brought to the attention of the lower court, administrative agency or quasi-judicial body need not be considered by a reviewing court, as they cannot be raised for the first time at that late stage.13 When a party deliberately adopts a certain theory and the case is decided upon that theory in the court below, he will not be permitted to change the same on appeal, because to permit him to do so would be unfair to the adverse party.14 Thus, if respondent retrieved the form on March 4, 1999 with the signature of Po, it can be correctly inferred that he is not the forger. Had the CAPEX form been returned to respondent without Po's signature, Villanueva or any officer of the petitioner's company could have readily noticed the lack of signature, and could have easily attested that the form was unsigned when it was released to respondent. Further, as correctly found by the NLRC in its original decision dated August 26, 2002, if respondent was the one who forged the signature of Po in the CAPEX form, there was no need for him to endorse the same to Villanueva and transmit it the next day. He could have easily forged the signature of Po on the same day that he prepared the CAPEX form and submitted it on the very same day to petitioner's main office without passing through any officer of petitioner. Accordingly, for want of substantial basis, in fact or in law, factual findings of an administrative agency, such as the NLRC, cannot be given the stamp of finality and conclusiveness normally accorded to it, as even decisions of administrative agencies which are declared "final" by law are not exempt from judicial review when so warranted. 15Contrary to petitioners assertion, therefore, this Court sees no error on the part of the CA when it made a new determination of the case and, upon this, reversed the ruling of the NLRC. As to the second issue, the law mandates that the burden of proving the validity of the termination of employment rests with the employer. Failure to discharge this evidentiary burden would necessarily mean that the dismissal was not justified and, therefore, illegal. Unsubstantiated suspicions, accusations, and conclusions of employers do not provide for legal justification for dismissing employees. In case of doubt, such cases should be resolved in favor of labor, pursuant to the social justice policy of labor laws and the Constitution.16

The termination letter17 addressed to respondent, dated May 20, 1999, provides that: We also conducted inquiries from persons concerned to get more information in (sic) this forgery. Some of your statements do not jibe with theirs. x x x However, this information which petitioner allegedly obtained from the "persons concerned" was not backed-up by any affidavit or proof. Petitioner did not even bother to name these resource persons. Petitioner based respondent's dismissal on its unsubstantiated suspicions and conclusion that since respondent was the custodian and the one who prepared the CAPEX forms, he had the motive to commit the forgery. However, as correctly found by the NLRC in its original Decision, respondent would not be benefited by the purchase of the subject equipment. The equipment would be for the use of petitioner company. With respect to the third issue, while We have previously held that employers are allowed a wider latitude of discretion in terminating the services of employees who perform functions which by their nature require the employers' full trust and confidence and the mere existence of basis for believing that the employee has breached the trust of the employer is sufficient,18 this does not mean that the said basis may be arbitrary and unfounded. The right of an employer to dismiss an employee on the ground that it has lost its trust and confidence in him must not be exercised arbitrarily and without just cause.19 Loss of trust and confidence, to be a valid cause for dismissal, must be based on a willful breach of trust20 and founded on clearly established facts. The basis for the dismissal must be clearly and convincingly established, but proof beyond reasonable doubt is not necessary.21 It must rest on substantial grounds and not on the employers arbitrariness, whim, caprice or suspicion; otherwise, the employee would eternally remain at the mercy of the employer. 22 The case of Philippine Airlines, Inc. v. Tongson,23 cited by the petitioner, is not applicable to the present case. In that case, PAL dismissed Tongson from service on the ground of corruption, extortion and bribery in the processing of PAL's passengers' travel documents. We upheld the validity of Tongson's dismissal because PAL's overwhelming documentary evidence reflects an unbroken chain which naturally leads to one fair and reasonable conclusion, that at the very least, respondent was involved in extorting money from PAL's passengers. We further said that even if there is no direct evidence to prove that the employees actually committed the offense, substantial proof based on documentary evidence is sufficient to warrant their dismissal from employment. In the case at bar, there is neither direct evidence nor substantial documentary evidence pointing to respondent as the one liable for the forgery of the signature of Po.1avvphi1 The cited case of Deles Jr. v. National Labor Relations Commission24 is also inapplicable. Therein dismissed employee, Deles Jr., himself admitted during the company investigation that he tampered with the company's sensitive equipment (the JTF Gravitometer No. 5). Thus, there existed sufficient basis for the finding that therein employee breached the trust and confidence of his employer. As for the final issue raised, petitioner's reliance on respondent's previous tardiness in reporting for work as a ground for his dismissal is likewise not meritorious. The correct rule has always been that such previous offense may be used as valid justification for dismissal from work only if the infractions are related to the subsequent offense upon which the basis of termination is decreed.25 His previous offenses were entirely separate and distinct from his latest alleged infraction of forgery. Hence, the same could no longer be utilized as an added justification for his dismissal. Besides, respondent had already been sanctioned for his prior infractions. To consider these offenses as justification for his dismissal would be penalizing respondent twice for the same offense.26 Respondent's illegal dismissal carries the legal consequences defined under Article 279 of the Labor Code, that is, an employee who is unjustly dismissed from work shall be entitled to reinstatement without loss of seniority rights and other privileges, and to the payment of his full backwages, inclusive of allowances, and to his other benefits or their monetary equivalent, computed from the time his compensation was withheld from him up to the time of his actual reinstatement.27

However, the Court finds that it would be best to award separation pay instead of reinstatement, in view of the strained relations between petitioner and respondent. Respondent was dismissed due to loss of trust and confidence and it would be impractical to reinstate an employee whom the employer does not trust, and whose task is to handle and prepare delicate documents. Under the doctrine of strained relations, the payment of separation pay has been considered an acceptable alternative to reinstatement when the latter option is no longer desirable or viable. On the one hand, such payment liberates the employee from what could be a highly oppressive work environment. On the other hand, the payment releases the employer from the grossly unpalatable obligation of maintaining in its employ a worker it could no longer trust. 28 In view of the foregoing, respondent is entitled to the payment of full backwages, inclusive of allowances, and other benefits or their monetary equivalent, computed from the date of his dismissal on May 20, 1999 up to the finality of this decision, and separation pay in lieu of reinstatement equivalent to one month salary for every year of service, computed from the time of his engagement by petitioner on August 1993 up to the finality of the decision.29 The awards of separation pay and backwages are not mutually exclusive and both may be given to the respondent. In Nissan North Edsa Balintawak, Quezon City v. Serrano, Jr.,30 the Court held that: The normal consequences of a finding that an employee has been illegally dismissed are, firstly, that the employee becomes entitled to reinstatement to his former position without loss of seniority rights and, secondly, the payment of backwages corresponding to the period from his illegal dismissal up to actual reinstatement. The statutory intent on this matter is clearly discernible. Reinstatement restores the employee who was unjustly dismissed to the position from which he was removed, that is, to his status quo ante dismissal, while the grant of backwages allows the same employee to recover from the employer that which he had lost by way of wages as a result of his dismissal. These twin remedies reinstatement and payment of backwages make the dismissed employee whole who can then look forward to continued employment. Thus, do these two remedies give meaning and substance to the constitutional right of labor to security of tenure. The two forms of relief are distinct and separate, one from the other. Though the grant of reinstatement commonly carries with it an award of backwages, the inappropriateness or non-availability of one does not carry with it the inappropriateness or non-availability of the other. x x x As the term suggests, separation pay is the amount that an employee receives at the time of his severance from the service and x x x is designed to provide the employee with "the wherewithal during the period that he is looking for another employment." In the instant case, the grant of separation pay was a substitute for immediate and continued re-employment with the private respondent Bank. The grant of separation pay did not redress the injury that is intended to be relieved by the second remedy of backwages, that is, the loss of earnings that would have accrued to the dismissed employee during the period between dismissal and reinstatement. Put a little differently, payment of backwages is a form of relief that restores the income that was lost by reason of unlawful dismissal; separation pay, in contrast, is oriented towards the immediate future, the transitional period the dismissed employee must undergo before locating a replacement job. x x x The grant of separation pay was a proper substitute only for reinstatement; it could not be an adequate substitute both for reinstatement and for backwages. (Emphasis supplied.) 31 The case is, therefore, remanded to the Labor Arbiter for the purpose of computing the proper monetary award due to the respondent. WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 86939, dated December 1, 2005 and February 17, 2006, respectively, are AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION that the order of reinstatement is deleted, and in lieu thereof, Petitioner Century Canning Corporation is DIRECTED to pay respondent separation pay. The case is REMANDED to the Labor Arbiter for the purpose of computing respondent's full backwages, inclusive of allowances, and other benefits or their monetary equivalent, computed from the date of his dismissal on May 20, 1999 up to the finality of the decision, and separation pay in lieu of reinstatement equivalent to one month salary for every year of service, computed from the time of his engagement by petitioner on August 1993 up to the finality of this decision. SO ORDERED. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Associate Justice

10

WE CONCUR: A.M. No. P-95-1167 February 9, 2010

CARMELITA LLEDO, Complainant, vs. ATTY. CESAR V. LLEDO, Branch Clerk of Court, Regional Trial Court, Branch 94, Quezon City,Respondent. RESOLUTION NACHURA, J.: May a government employee, dismissed from the service for cause, be allowed to recover the personal contributions he paid to the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS)? This is the question that confronts this Court in the instant case, the factual antecedents of which are as follows: On December 21, 1998, this Court promulgated a Decision1 in the above-captioned case, dismissing from the service Atty. Cesar V. Lledo, former branch clerk of court of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 94. Cesars wife, Carmelita, had filed an administrative case against him, charging the latter with immorality, abandonment, and conduct unbecoming a public official. During the investigation, it was established that Cesar had left his family to live with another woman with whom he also begot children. He failed to provide support for his family. The investigating judge recommended Cesars dismissal from the service. The Office of the Court Administrator (OCA) adopted the recommendation. The Court, in its December 21, 1998 Decision, disposed of the case in this wise: WHEREFORE, Cesar V. Lledo, branch clerk of court of RTC, Branch 94, Quezon City, is hereby DISMISSED from the service, with forfeiture of all retirement benefits and leave credits and with prejudice to reemployment in any branch or instrumentality of the government, including any government-owned or controlled corporation. This case is REFERRED to the IBP Board of Governors pursuant to Section 1 of Rule 139-B of the Rules of Court. SO ORDERED.2 In a letter3 dated January 15, 1999, Carmelita and her children wrote to then Chief Justice Hilario G. Davide, Jr., begging for humane consideration and asking that part of the money due Cesar be applied to the payment of the arrearages of their amortized house and lot then facing foreclosure by the GSIS. They averred that Cesars abandonment had been painful enough; and to lose their home of 26 years would be even more painful and traumatic for the children. The Court directed the OCA to comment. The OCA recommended that the Courts December 21, 1998 Decision be reconsidered insofar as the forfeiture of Cesars leave credits was concerned, underscoring, however, that said benefits would only be released to Carmelita and her children.4 In a Resolution dated August 3, 1999,5 the Court resolved to deny the motion for reconsideration for lack of merit. On April 3, 2006, Cesar L. Lledo, Jr., Cesars son, wrote a letter6 to then Chief Justice Artemio V. Panganiban. He related that his father had been bedridden after suffering a severe stroke and acute renal failure. He had been abandoned by his mistress and had been under Cesar Jr.s care since 2001. The latter appealed to the Court to reconsider its December 21, 1998 Decision, specifically the forfeiture of leave credits, which money would be used to pay for his fathers medical expenses. Cesar Jr. asked the Court for retroactive application of the Courts ruling subsequent to his fathers dismissal, wherein the Court ruled that despite being dismissed from the service, government employees are entitled to the monetary equivalent of their leave credits since these were earned prior to dismissal.

11

Treating the letter as a motion for reconsideration, the Court, on May 3, 2006, granted the same, specifically on the forfeiture of accrued leave credits.7 Cesar Jr. wrote the Court again on November 27, 2006, expressing his gratitude for the Courts consideration of his request for his fathers leave credits. He again asked for judicial clemency in connection with his fathers claim for refund of the latters personal contributions to GSIS.8 The Court directed the GSIS to comment, within 10 days from notice, on Cesar Jr.s letter.9 For failing to file the required Comment, the Court, in a Resolution dated December 11, 2007,10 required the GSIS to show cause why it should not be held in contempt for failure to comply with the Resolution directing it to file its Comment. The Court reiterated its December 11, 2007 Resolution on June 17, 2008, and directed compliance. In a letter11 dated April 16, 2009, Jason C. Teng, Regional Manager of the GSIS Quezon City Regional Office, explained that a request for a refund of retirement premiums is disallowed. He explained: The rate of contribution for both government and personal shares of retirement premiums was actuarially computed to allow the GSIS to generate enough investment returns to be able to pay off future claims. During actuarial computation, the expected demographics considered the percentages of different types of future claims (and non-claims). As such, if those that were expected to have no future claim (e.g. those with forfeited retirement benefits) were suddenly allowed to receive claims for payment of benefits, this would have a negative impact on the financial viability of the GSIS.1avvphi1 Even as the Court noted the letter in its June 30, 2009 Resolution,12 it further required the Board of Directors of the GSIS (GSIS Board) to file a separate Comment within 10 days from notice. In its Comment,13 the GSIS Board said that Cesar is not entitled to the refund of his personal contributions of the retirement premiums because "it is the policy of the GSIS that an employee/member who had been dismissed from the service with forfeiture of retirement benefits cannot recover the retirement premiums he has paid unless the dismissal provides otherwise." The GSIS Board pointed out that the Courts Decision did not provide that Cesar is entitled to a refund of his retirement premiums. There is no gainsaying that dismissal from the service carries with it the forfeiture of retirement benefits. Under the Uniform Rules in Administrative Cases in the Civil Service, it is provided that:14 Section 58. Administrative Disabilities Inherent in Certain Penalties. a. The penalty of dismissal shall carry with it that of cancellation of eligibility, forfeiture of retirement benefits, and the perpetual disqualification for reemployment in the government service, unless otherwise provided in the decision. However, in the instant case, Cesar Jr. seeks only the return of his fathers personal contributions to the GSIS. He is not claiming any of the benefits that Cesar would have been entitled to had he not been dismissed from the service, such as retirement benefits. To determine the propriety of Cesar Jr.s request, a reexamination of the laws governing the GSIS is in order. The GSIS was created in 1936 by Commonwealth Act No. 186. It was intended to "promote the efficiency and welfare of the employees of the Government of the Philippines" and to replace the pension systems in existence at that time. 15 Section 9 of Commonwealth Act No. 186 states: Section 9. Effect of dismissal or separation from service. Upon dismissal for cause of a member of the System, the benefits under his membership policy shall be automatically forfeited to the System, except one-half of the cash or surrender value, which amount shall be paid to such member, or in case of death, to his beneficiary. In other cases of

12

separation before maturity of a policy, the Government contributions shall cease, and the insured member shall have the following options: (a) to collect the cash surrender value of the policy; or (b) to continue the policy by paying the full premiums thereof; or (c) to obtain a paid up or extended term insurance in such amount or period, respectively, as the paid premiums may warrant, in accordance with the conditions contained in said policy; o[r] (d) to avail himself of such other options as may be provided in the policy.16 In 1951, Commonwealth Act No. 186 was amended by Republic Act (R.A.) No. 660. R.A. No. 660 amended Sections 2(a), (d), and (f); 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; and 16 of Commonwealth Act No. 186. R.A. No. 660 likewise added new provisions to the earlier law, one of which reads: Section 8. The following new sections are hereby inserted in Commonwealth Act Numbered One hundred and eighty-six: II. Retirement Insurance Benefit "Section 11. (a) Amount of annuity. Upon retirement a member shall be automatically entitled to a life annuity payable monthly for at least five years and thereafter as long as he live. (sic) The amount of the monthly annuity at the age of fifty-seven years shall be twenty pesos, plus, for each year of service rendered after the approval of this Act, one and six-tenths per centum of the average monthly salary received by him during the last five years of service, plus, for each year of service rendered prior to the approval of this Act, if said service was at least seven years, one and two-tenths per centum of said average monthly salary: Provided, That this amount shall be adjusted actuarially if retirement be at an age other than fifty-seven years: Provided, further, That the maximum amount of monthly annuity at age fifty-seven shall not in any case exceed two-thirds of said average monthly salary or five hundred pesos, whichever is the smaller amount: And provided, finally, That retirement benefit shall be paid not earlier than one year after the approval of this Act. In lieu of this annuity, he may prior to his retirement elect one of the following equivalent benefits: "(1) Monthly annuity during his lifetime; "(2) Monthly annuity during the joint-lives of the employee and his wife or other designated beneficiary, which annuity, however, shall be reduced upon the death of either to one-half and be paid to the survivor; "(3) For those who are at least sixty-five years of age, lump sum payment of present value of annuity for first five years and future annuity to be paid monthly; or "(4) Such other benefit as may be approved by the System. "(b) Survivors benefit. Upon death before he becomes eligible for retirement, his beneficiaries as recorded in the application of retirement annuity filed with the System shall be paid his own premiums with interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly. If on his death he is eligible for retirement, then the automatic retirement annuity or the annuity chosen by him previously shall be paid accordingly. "(c) Disability benefit. If he becomes permanently and totally disabled and his services are no longer desirable, he shall be discharged and paid his own contributions with interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly, if he has served less than five years; if he has served at least five years but less than fifteen years, he shall be paid also the corresponding employer's premiums, without interest, described in subsection (a) of section five hereof; and if he has served at least fifteen years he shall be retired and be entitled to the benefit provided under subsection (a) of this section. "(d) Upon dismissal for cause or on voluntary separation, he shall be entitled only to his own premiums and voluntary deposits, if any, plus interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly." 17 Thus, Section 11(d) of R.A. No. 660 should be deemed to have amended Commonwealth Act No. 186.

13

In 1977, then President Ferdinand Marcos issued Presidential Decree (P.D.) No. 1146, an act "Amending, Expanding, Increasing and Integrating the Social Security and Insurance Benefits of Government Employees and Facilitating the Payment thereof under Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended, and for other purposes." Section 4 of P.D. No. 1146 reads: Section 4. Effect of Separation from the Service. A member shall continue to be a member, notwithstanding his separation from the service and, unless the terms of his separation provide otherwise, he shall be entitled to whatever benefits which shall have accrued or been earned at the time of his separation in the event of any contingency compensable under this Act. There is no provision in P.D. No. 1146 dealing specifically with GSIS members dismissed from the service for cause, or their entitlement to the premiums they have paid. Subsequently, R.A. No. 8291 was enacted in 1997, and it provides: Section 1. Presidential Decree No. 1146, as amended, otherwise known as the "Revised Government Service Insurance Act of 1977", is hereby amended to read as follows: xxxx SEC. 4. Effect of Separation from the Service. A member separated from the service shall continue to be a member, and shall be entitled to whatever benefits he has qualified to in the event of any contingency compensable under this Act. It is noteworthy that none of the subsequent laws expressly repealed Section 9 of Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended. In fact, none of the subsequent laws expressly repealed the earlier laws. Be that as it may, we must still resolve the issue of whether the same has been impliedly repealed. We answer in the negative. As a general rule, repeals by implication are not favored. When statutes are in pari materia, they should be construed together. A law cannot be deemed repealed unless it is clearly manifested that the legislature so intended it.18 The repealing clause of P.D. No. 1146 reads: Section 48. Repealing Clause. All laws or parts of law specifically inconsistent herewith shall be considered amended or repealed accordingly. On the other hand R.A. No. 8291s repealing clause states: SEC. 3. Repealing Clause. All laws and any other law or parts of law specifically inconsistent herewith are hereby repealed or modified accordingly: Provided, That the rights under existing laws, rules and regulations vested upon or acquired by an employee who is already in the service as of the effectivity of this Act shall remain in force and effect: Provided, further, That subsequent to the effectivity of this Act, a new employee or an employee who has previously retired or separated and is reemployed in the service shall be covered by the provisions of this Act. This Court has previously determined the nature of similarly-worded repealing clauses. Thus: The holding of this Court in Mecano vs. COA is instructive: "The question that should be asked is: What is the nature of this repealing clause? It is certainly not an express repealing clause because it fails to identify or designate the act or acts that are intended to be repealed. Rather, it is an example of a general repealing provision, as stated in Opinion No. 73, s. 1991. It is a clause which predicates the intended repeal under the condition that a substantial conflict must be found in existing and prior acts. The failure to add a specific repealing clause indicates that the intent was not to repeal any existing law, unless an

14

irreconcilable inconsistency and repugnancy exist in the terms of the new and old laws. This latter situation falls under the category of an implied repeal."19 There are two accepted instances of implied repeal. The first takes place when the provisions in the two acts on the same subject matter are irreconcilably contradictory, in which case, the later act, to the extent of the conflict, constitutes an implied repeal of the earlier one. The second occurs when the later act covers the whole subject of the earlier one and is clearly intended as a substitute; thus, it will operate to repeal the earlier law.20 Addressing the second instance, we pose the question: were the later enactments intended to substitute the earlier ones? We hold that there was no such substitution. P.D. No. 1146 was not intended to replace Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended by R.A. No. 660, but "to expand and improve the social security and insurance programs administered by the Government Service Insurance System." 21 Thus, as the above-quoted repealing clause indicates, only the laws or parts of law specifically inconsistent with P.D. No. 1146 were considered amended or repealed.22 In fact, Section 34 of P.D. No. 1146 mandates that the GSIS, as created and established under Commonwealth Act No. 186, shall implement the provisions of that law. Moreover, Section 13 states: Section 13. Retirement Option. Employees who are in the government service upon the effectivity of this Act shall, at the time of their retirement, have the option to retire under this Act or under Commonwealth Act No. 186, as previously amended. Accordingly, Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended, had not been abrogated by P.D. No. 1146. Meanwhile, R.A. No. 8291, although enacted to amend P.D. No. 1146, did not expressly repeal Commonwealth Act No. 186. Under the first instance of implied repeal, we are guided by the principle that in order to effect a repeal by implication, the later statute must be so irreconcilably inconsistent with and repugnant to the existing law that they cannot be reconciled and made to stand together. The clearest case of inconsistency must be made before the inference of implied repeal can be drawn, for inconsistency is never presumed.23 We now examine the effect of the later statutes on the provision specifically dealing with employees dismissed for cause. We again quote Section 11(d) of Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended: (d) Upon dismissal for cause or on voluntary separation, he shall be entitled only to his own premiums and voluntary deposits, if any, plus interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly. Compare this with Section 4 of P.D. No. 1146, to wit: Section 4. Effect of Separation from the Service. A member shall continue to be a member, notwithstanding his separation from the service and, unless the terms of his separation provide otherwise, he shall be entitled to whatever benefits which shall have accrued or been earned at the time of his separation in the event of any contingency compensable under this Act. and Section 1 of R.A. No. 8291, which amended Section 4 of P.D. No. 1146 and the law in force at the time of Cesars dismissal from the service: SEC. 4. Effect of Separation from the Service. A member separated from the service shall continue to be a member, and shall be entitled to whatever benefits he has qualified to in the event of any contingency compensable under this Act. There is no manifest inconsistency between Section 11(d) of Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended, and Section 4 of R.A. No. 8291. The latter provision is a general statement intended to cover members separated from the service whether the

15

separation is voluntary or involuntary, and whether the same was for cause or not. Moreover, the same deals only with the benefits the member is entitled to at the time of separation. For the latter law to be deemed as having repealed the earlier law, it is necessary to show that the statutes or statutory provisions deal with the same subject matter and that the latter be inconsistent with the former. There must be a showing of repugnance, clear and convincing in character. The language used in the later statute must be such as to render it irreconcilable with what had been formerly enacted. An inconsistency that falls short of that standard does not suffice. 24 As mentioned earlier, neither P.D. No. 1146 nor R.A. No. 8291 contains any provision specifically dealing with employees dismissed for cause and the status of their personal contributions. Thus, there is no inconsistency between Section 11(d) of Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended, and Section 4 of P.D. No. 1146, and, subsequently, R.A. No. 8291. The inevitable conclusion then is that Section 11(d) of Commonwealth Act No. 186, as amended, continues to govern cases of employees dismissed for cause and their claims for the return of their personal contributions. Finally, it should be remembered that the GSIS laws are in the nature of social legislation, to be liberally construed in favor of the government employees.25 The money subject of the instant request consists of personal contributions made by the employee, premiums paid in anticipation of benefits expected upon retirement. The occurrence of a contingency, i.e., his dismissal from the service prior to reaching retirement age, should not deprive him of the money that belongs to him from the outset. To allow forfeiture of these personal contributions in favor of the GSIS would condone undue enrichment. Pursuant to the foregoing discussion, Cesar is entitled to the return of his premiums and voluntary deposits, if any, with interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly. WHEREFORE, the foregoing premises considered, the Government Service Insurance System is hereby DIRECTED to return to Atty. Cesar Lledo his own premiums and voluntary deposits, if any, plus interest of three per centum per annum, compounded monthly. SO ORDERED. ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA G.R. No. 188722 February 1, 2012

BANK OF LUBAO, INC., Petitioner, vs. ROMMEL J. MANABAT and the NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, Respondents. DECISION REYES, J.: Nature of the Petition This is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court filed by the Bank of Lubao, Inc. (petitioner) assailing the Decision1 dated April 24, 2009 and Resolution2 dated July 7, 2009 issued by the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP No. 106419. The Antecedent Facts Sometime in 2001, Rommel J. Manabat (respondent) was hired by petitioner Bank of Lubao, a rural bank, as a Market Collector. Subsequently, the respondent was assigned as an encoder at the Bank of Lubaos Sta. Cruz Extension Office, which he manned

16

together with two other employees, teller Susan P. Lingad (Lingad) and May O. Manasan. As an encoder, the respondents primary duty is to encode the clients deposits on the banks computer after the same are received by Lingad. In November 2004, an initial audit on the Bank of Lubaos Sta. Cruz Extension Office conducted by the petitioner revealed that there was a misappropriation of funds in the amount of P3,000,000.00, more or less. Apparently, there were transactions entered and posted in the passbooks of the clients but were not entered in the banks book of accounts. Further audit showed that there were various deposits which were entered in the banks computer but were subsequently reversed and marked as "error in posting". On November 17, 2004, the respondent, through a memorandum sent by the petitioner, was asked to explain in writing the discrepancies that were discovered during the audit. On November 19, 2004, the respondent submitted to the petitioner his letter-explanation which, in essence, asserted that there were times when Lingad used the banks computer while he was out on errands. On December 11, 2004, an administrative hearing was conducted by the banks investigating committee where the respondent was further made to explain his side. Subsequently, the investigating committee concluded that the respondent conspired with Lingad in making fraudulent entries disguised as error corrections in the banks computer. On August 9, 2005, the petitioner filed several criminal complaints for qualified theft against Lingad and the respondent with the Municipal Trial Court (MTC) of Lubao, Pampanga. Thereafter, citing serious misconduct tantamount to willful breach of trust as ground, it terminated the respondents employment effective September 1, 2005. On September 26, 2005, the respondent filed a Complaint3 for illegal dismissal with the Regional Arbitration Branch of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) in San Fernando City, Pampanga. In the said complaint, the respondent, to bolster his claim that there was no valid ground for his dismissal, averred that the charge against him for qualified theft was dismissed for lack of sufficient basis to conclude that he conspired with Lingad. The respondent sought an award for separation pay, full backwages, 13th month pay for 2004 and moral and exemplary damages. For its part, the petitioner insists that the dismissal of the respondent is justified, asserting the February 14, 2006 Audit Report which confirmed the participation of the respondent in the alleged misappropriations. Likewise, the petitioner asserted that the dismissal of the qualified theft charge against the respondent is immaterial to the validity of the ground for the latters dismissal. The Labor Arbiters Decision On February 28, 2007, the Labor Arbiter (LA) rendered a decision4 sustaining the respondents claim of illegal dismissal thus ordering the petitioner to reinstate the respondent to his former position and awarding the latter backwages in the amount of P111,960.00 and 13th month pay in the amount of P6,220.00. The LA opined that the petitioner failed to adduce substantial evidence that there was a valid ground for the respondents dismissal. Further, the February 14, 2006 Audit Report that was adduced by the petitioner in evidence was disregarded by the LA since it was unsigned. The petitioner appealed the foregoing disposition to the NLRC, submitting a new audit report dated April 30, 2007. Pending appeal, the petitioner sent the respondent a letter5 dated April 30, 2007 requiring him to report for work on May 4, 2007 pursuant to the reinstatement order of the LA. The said letter was served to the respondent on May 3, 2007 but he refused to receive the same. The NLRCs Decision On July 21, 2008, the NLRC rendered a Decision6 affirming the February 28, 2007 Decision of the LA. The NLRC held that it was sufficiently established that only Lingad was the one responsible for the said misappropriations. Further, the NLRC asserted that the February 14, 2006 and April 30, 2007 audit reports presented by the petitioner could not be given evidentiary weight as the

17

same were executed after the respondent had already been dismissed. The petitioner sought reconsideration of the said July 21, 2008 Decision but it was denied by the NLRC in its Resolution7 dated September 22, 2009. Subsequently, the petitioner filed a Petition for Certiorari8 with the CA alleging that the NLRC and the LA gravely abused their discretion in ruling that the respondent had been illegally dismissed. The CA Decision On April 24, 2009, the CA rendered the herein assailed decision9 denying the petition for certiorari filed by the petitioner. However, the CA held that the respondent is entitled to separation pay equivalent to one-month salary for every year of service in lieu of reinstatement and backwages to be computed from the time of his illegal dismissal until the finality of the said decision. The CA agreed with the LA and the NLRC that the petitioner failed to establish by substantial evidence that there was indeed a valid ground for the respondents dismissal. Nevertheless, the CA held that the petitioner should pay the respondent separation pay since the latter did not pray for reinstatement before the LA and that the same would be in the best interest of the parties considering the animosity and antagonism that exist between them. The CA stated the following: With respect to monetary awards, a finding that an employee has been illegally dismissed ordinarily entitles him to reinstatement to his former position without loss of seniority rights and to the payment of backwages. In this case, however, private respondent did not pray for reinstatement before the Labor Arbiter. This being the case, the employer should pay him separation pay in lieu [of] reinstatement. This is only just and practical because reinstatement of private respondent will no longer be in the best interest of both parties considering the animosity and antagonism that exist between them brought about by the filing of charges in the criminal as well as in the labor proceedings. Consequently, private respondent is entitled to separation pay equivalent to one month pay for every year of service up to the finality of this judgment, as an alternative to reinstatement. With respect to his backwages, where reinstatement is no longer possible, it shall be computed from the time of the employees illegal termination up to the finality of this decision, without qualification or deduction.10 (citations omitted) Hence, the fallo of the CA Decision reads: WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The assailed Decision and Resolution of the NLRC are AFFIRMED with the MODIFICATION that private respondent is entitled to separation pay equivalent to one month salary for every year of service in lieu of reinstatement and backwages to be computed from the time of his illegal dismissal until the finality of this Decision. SO ORDERED.11 The petitioners Motion for Reconsideration12 was denied by the CA in its Resolution13 dated July 7, 2009. Undaunted, the petitioner instituted the instant petition for review on certiorari before this Court asserting the following arguments: (1) the CA erred in awarding separation pay in favor of the respondent in lieu of reinstatement considering that the appeal before it only involved the issue of the legality or illegality of the respondents dismissal; (2) an award of separation pay to the respondent is not proper in this case considering that, in his complaint, he merely prayed for reinstatement and not payment of separation pay; and (3) the CA erred in awarding backwages in favor of the respondent since it acted in good faith when it terminated the respondents employment. In his Comment,14 the respondent asserted that the CA did not err in ordering the payment of separation pay in his favor in lieu of reinstatement since there is already a strained relationship between him and the petitioner. He intimated that the petitioner had previously filed various criminal charges against him for qualified theft thus effectively rendering his reinstatement to his former position in the Bank of Lubao impracticable. Issues

18

In sum, the issues to be resolved by this Court in the instant case are the following: (1) whether the CA erred in ordering the petitioner to pay the respondent separation pay in lieu of reinstatement; and (2) whether the respondent is entitled to payment of backwages. The Courts Ruling This Court notes that the LA, the NLRC and the CA unanimously ruled that the respondent was illegally dismissed. Factual findings of quasi-judicial bodies like the NLRC, if supported by substantial evidence, are accorded respect and even finality by this Court, more so when they coincide with those of the LA. Such factual findings are given more weight when the same are affirmed by the CA. We find no reason to depart from the foregoing rule. First Issue: Separation Pay in Lieu of Reinstatement At the outset, it should be stressed that a determination of the applicability of the doctrine of strained relations is essentially a factual question and, thus, not a proper subject in the instant petition.15 The well-entrenched rule in our jurisdiction is that only questions of law may be entertained by this Court in a petition for review on certiorari. This rule, however, is not ironclad and admits certain exceptions, such as when, inter alia, the findings of fact are conflicting.16 Here, in view of the conflicting findings of the NLRC and the CA, this Court is constrained to pass upon the propriety of the application of the doctrine of strained relations to justify the award of separation pay to the respondent in lieu of reinstatement. The law on reinstatement is provided for under Article 279 of the Labor Code of the Philippines: Article 279. Security of Tenure. - In cases of regular employment, the employer shall not terminate the services of an employee except for a just cause or when authorized by this Title. An employee who is unjustly dismissed from work shall be entitled to reinstatement without loss of seniority rights and other privileges and to his full backwages, inclusive of allowances, and to his other benefits or their monetary equivalent computed from the time his compensation was withheld from him up to the time of his actual reinstatement. (emphasis supplied) Under the law and prevailing jurisprudence, an illegally dismissed employee is entitled to reinstatement as a matter of right. However, if reinstatement would only exacerbate the tension and strained relations between the parties, or where the relationship between the employer and the employee has been unduly strained by reason of their irreconcilable differences, particularly where the illegally dismissed employee held a managerial or key position in the company, it would be more prudent to order payment of separation pay instead of reinstatement.17 Under the doctrine of strained relations, the payment of separation pay is considered an acceptable alternative to reinstatement when the latter option is no longer desirable or viable. On one hand, such payment liberates the employee from what could be a highly oppressive work environment. On the other hand, it releases the employer from the grossly unpalatable obligation of maintaining in its employ a worker it could no longer trust.18 In such cases, it should be proved that the employee concerned occupies a position where he enjoys the trust and confidence of his employer; and that it is likely that if reinstated, an atmosphere of antipathy and antagonism may be generated as to adversely affect the efficiency and productivity of the employee concerned.19 Here, we agree with the CA that the relations between the parties had been already strained thereby justifying the grant of separation pay in lieu of reinstatement in favor of the respondent. First, it cannot be gainsaid that the petitioners reinstatement to his former position would only serve to intensify the atmosphere of antipathy and antagonism between the parties. Undoubtedly, the petitioners filing of various criminal complaints against the

19

respondent for qualified theft and the subsequent filing by the latter of the complaint for illegal dismissal against the latter, taken together with the pendency of the instant case for more than six years, had caused strained relations between the parties. Second, considering that the respondents former position as bank encoder involves the handling of accounts of the depositors of the Bank of Lubao, it would not be equitable on the part of the petitioner to be ordered to maintain the former in its employ since it may only inspire vindictiveness on the part of the respondent. Third, the refusal of the respondent to be re-admitted to work is in itself indicative of the existence of strained relations between him and the petitioner. In the case of Lagniton, Sr. v. National Labor Relations Commission,20the Court held that the refusal of the dismissed employee to be re-admitted is constitutive of strained relations: It appears that relations between the petitioner and the complainants have been so strained that the complainants are no longer willing to be reinstated. As such reinstatement would only exacerbate the animosities that have developed between the parties, the public respondents were correct in ordering instead the grant of separation pay to the dismissed employees in the interest of industrial peace.21 Time and again, this Court has recognized that strained relations between the employer and employee is an exception to the rule requiring actual reinstatement for illegally dismissed employees for the practical reason that the already existing antagonism will only fester and deteriorate, and will only worsen with possible adverse effects on the parties, if we shall compel reinstatement; thus, the use of a viable substitute that protects the interests of both parties while ensuring that the law is respected.22 Second Issue: Backwages Anent the second issue, the petitioner claimed that the respondent is not entitled to the payment of backwages considering that there was no bad faith on its part when it terminated the latters employment. The petitioner insists that it is within its prerogative to dismiss the respondent on the basis of loss of trust and confidence. We do not agree. The arguments raised by the petitioner with regard to the issue of backwages, essentially, attacks the factual findings of the CA, the NLRC and the LA. As stated earlier, subject to well-defined exceptions, factual questions may not be raised in a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 as this Court is not a trier of facts. The petitioner failed to assert any circumstance which would impel this Court to disregard the findings of fact of the lower tribunals on the propriety of the award of backwages in favor of the respondent. However, the backwages that should be awarded to the respondent should be modified. Employees who are illegally dismissed are entitled to full backwages, inclusive of allowances and other benefits or their monetary equivalent, computed from the time their actual compensation was withheld from them up to the time of their actual reinstatement. But if reinstatement is no longer possible, the backwages shall be computed from the time of their illegal termination up to the finality of the decision.23 Thus, when there is an order of reinstatement, the computation of backwages shall be reckoned from the time of illegal dismissal up to the time that the employee is actually reinstated to his former position.1wphi1 Pursuant to the order of reinstatement rendered by the LA, the petitioner sent the respondent a letter requiring him to report back to work on May 4, 2007. Notwithstanding the said letter, the respondent opted not to report for work. Thus, it is but fair that the backwages that should be awarded to the respondent be computed from the time that the respondent was illegally dismissed until the time when he was required to report for work, i.e. from September 1, 2005 until May 4, 2007. It is only during the said period that the respondent is deemed to be entitled to the payment of backwages. The fact that the CA, in its April 4, 2009 decision, ordered the payment of separation pay in lieu of the respondents reinstatement would not entitle the latter to backwages. It bears stressing that decisions of the CA, unlike that of the LA, are not immediately executory. Accordingly, the petitioner should only pay the respondent backwages from September 1, 2005, the date

20

when the respondent was illegally dismissed, until May 4, 2007, the date when the petitioner required the former to report to work.1wphi1 WHEREFORE, in consideration of the foregoing disquisitions, the instant petition is PARTIALLY GRANTED. The Decision dated April 24, 2009 and Resolution dated July 7, 2009 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 106419 are hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION. The petitioner is ordered to pay the respondent backwages from September 1, 2005 until May 4, 2007. For this purpose, the case is hereby REMANDED to the Labor Arbiter for the computation of the amounts due the respondent. SO ORDERED. BIENVENIDO L. REYES Associate Justice

21

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi