Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

67 Hammond02

Transféré par

Iryna PigovskaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

67 Hammond02

Transféré par

Iryna PigovskaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dating Bonaventure's Inception as Regent Master

Jay M. Hammond

Franciscan Studies, Volume 67, 2009, pp. 179-226 (Article)

Published by Franciscan Institute Publications DOI: 10.1353/frc.0.0041

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/frc/summary/v067/67.hammond02.html

Access Provided by State Library in Aarhus at 06/20/12 8:56PM GMT

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

In light of the careful work of Joshua Benson who argues that the De reductione is the second part to Bonaventures inception sermon,1 this article will date the De reductione by determining when he incepted.2 This is not an easy task because the date of his inception has been a point of confusion within Bonaventurian scholarship. Scholars date it as early as 1248 and as late as 1257. Within those nine years they assign various scenarios regarding his status as regent master. For example, the most common scenario has Bonaventure incepting in 1253 or 1254 and assuming the Franciscan Chair in theology, but only teaching in the Franciscan convent, unrecognized by the university until either 1256 or 1257.3 My thesis is that Bonaventure incepted in April 1254 to replace William of Middleton who relinquished the Franciscan chair in the wake of the Lenten riot of 1253.4 To argue this thesis, the paper divides into three parts. The first will briefly present the various dating for Bonaventures inception. The second will examine all the thirteenth and fourteenth

1 Published in this volume, Joshua Benson, Identifying the Literary Genre of the De reductione artium ad theologiam: Bonaventures Inaugural Lecture at Paris, Franciscan Studies 66 (2008): 149-78. I would like to thank both Joshua Benson and James Ginther for the many conversations regarding Bonaventures chronology during his academic career at Paris. 2 The critical edition for the De reductione artium ad theologiam is: S. Bonaventurae opera theologica selecta, vol. 5, Cura PP. Collegii S. Bonaventurae (Florence: Ad Claras Aquas, 1934), 215-28. 3 The next issue of Franciscan Studies will contain my essay, Dating Bonaventures Recognition as Regent Master, which argues the seculars accepted him into the consortium magistrorum at the time he incepted in 1254. 4 By arguing this thesis, I intend to correct my previous dating of the De reductione in the entry for Bonaventure in the New Catholic Encyclopedia, second edition, vol. 2 (Detroit: Gale, 2003), 483b: Considering the related issue of the self-sufficiency of Aristotelianism, it is also likely that [Bonaventure] wrote at this time (1269-70?) On the Reduction of the Arts to Theology, a mature and compact expression of his synthesis of retracing all knowledge and philosophy to a Christian wisdom-theology based on Scripture. However, a precise date for this text remains elusive, and some scholars date it around 1256.

Franciscan Studies 67 (2009)

179

180

Jay M. HaMMond

century sources that are used for determining Bonaventures chronology so as to establish the evidence for calculating his inception. And third, building upon the evidence gleaned from those witnesses, I will present a narrative chronology that details events surrounding Bonaventures inception in April 1254.

i. various Dating of Bonaventures inception as Master

Scholars assign various dates to his inception, which has caused much confusion. The Quaracchi editors of the Opera omnia, Robinson, Gilson, Moorman, and Crowley claim Bonaventure incepted in 1248;5 Robson alone gives a 1252 date;6 Callebaut, Longpr, the Spanish editors of the Obras de San Buenaventura, Abate, Bonafede, the earlier Brady, the later Hayes, and Hammond give a date of 1253;7 Pelster, Glorieux, the Quaracchi editors of the Opera theologica selecta, Veuthey, the earlier Bougerol, Cousins, Schlosser and

5 S. Bonaventurae opera omnia, vol. 10 (Quaracchi: Collegii S. Bonaventurae, 1902), 42-43; Paschal Robinson, Bonaventure, St. The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907), 649a; Etienne Gilson, The Philosophy of St. Bonaventure (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1938), 10; John Moorman, A History of the Franciscan Order: From Its Origins to the Year 1517 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 140; Theodore Crowley, St. Bonaventure Chronology Reappraisal, Franziskanische Studien 56 (1974): 318, 320, 322. 6 Michael Robson, Saint Bonaventure, in The Medieval Theologians, edited by G. R. Evans (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 187. 7 Andr Callebaut, Lentre de S. Bonaventure dans lOrdre des Frres Mineurs 1243, La France franciscaine 4 (1921): 44-45, 47; Ephrem Longpr, Bonaventure, Saint, Dictionnaire de spiritualit, vol. 1 (Paris: Beauchesne, 1937), c. 1768; Obras de San Buenaventura, vol. 1 (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1945), 9; Giuseppe Abate, Per la storia e la cronologia di S. Bonaventura, O. Min. (c. 1217-1274), Miscellanea Francescana 50 (1950): 97-111; Giulio Bonafede, San Bonaventura (Benevento: Cenacolo Bonaventuriano, 1961), 6; Ignatius Brady, Bonaventure, St., New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967), 658b; Zachary Hayes, Bonaventure: Mystical Writings (New York: Crossroad, 1999), 16; Jay Hammond, Bonaventure, St., New Catholic Encyclopedia, 479b.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

181

Delio opt for 1253 or 1254;8 the later Bougerol, Quinn, the earlier Hayes, Noone, Hauser, and Cullen hold for a 1254 date;9 the later Brady posits a 1255 date;10 Bettoni and Dufeil push the inception back to 1257.11 Table 1 highlights the disparity between the last two studies that focus specifically on Bonaventures chronology during his time at Paris. Table 1: Disputed dates in Bonaventures Chronology12 Key Dates Born Studied Arts Quinn (1972) 1217 1235-1243 Crowley (1974) 1221 1234-38*

8 Franz Pelster, Literargeschichtliche Probleme im Anschlu an die Bonaventuraausgabe von Quaracchi, Zeitschrift fr katholische Theologie 48 (1924): 524-30; Palmon Glorieux, DAlexandre de Hals Pierre Auriol: La suite des matres franciscains de Paris au XIIIe sicle, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 26 (1933): 265-75, 280-81; S. Bonaventurae opera theologica selecta, vol. 5 (Quaracchi, 1934), vii-ix; Lon Veuthey, Bonaventura, S., Enciclopedia filosofica, vol. 1 (Rome: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1957), 745a; Jacques Guy Bougerol, Introduction ltude de saint Bonaventure (Tournai: Descle, 1961), 13; Ewert Cousins, Bonaventure and the Coincidence of Opposites (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1978), 35, and Bonaventure, in The Classics of Western Spirituality (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 7; Marianne Schlosser, Bonaventura begegnen (Augsburg: Sankt-Ulrich-Verlag, 2000), 5; and Ilia Delio, Simply Bonaventure: An Introduction to His Life, Thought and Writings (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2001), 22. 9 Jacques Guy Bougerol, Introduction Saint Bonaventure, second edition (Paris: J. Vrin, 1988), 5; John Quinn, Chronology of St. Bonaventure (1217-1257), Franciscan Studies 32 (1972): 180-81, 186, and Bonaventure, St., in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, vol. 2, ed. Joseph Strayer (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1983), 313; Zachary Hayes, Bonaventure: Mystery of the Triune God, in The History of Franciscan Theology, ed. Kenan Osborne (St. Bonaventure: Franciscan Institute, 1994), 40; Timothy Noone and Rollen Houser, Saint Bonaventure, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bonaventure, 2005); Christopher Cullen, Bonaventure (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 11. 10 Ignatius Brady, The Writings of Saint Bonaventure Regarding the Franciscan Order, in San Bonaventura Maestro di Vita Francescana e di Sapienza Cristiana, vol. 1, ed. Alfonso Pompei (Rome: San Bonaventura, 1976), 91. 11 Efrem Bettoni, S. Bonaventura (Brescia: La Scuola, 1945), 9; MichelMarie Dufeil, Guillaume de Saint-Amour et la Polmique Universitaire Parisienne, 1250-1259 (Paris: ditions A. et J. Picard, 1972), 158. 12 Quinn, Chronology, 186 and Chronology, 322. An asterisk signals where I infer dates from those Crowley provides.

182

Jay M. HaMMond

Baccalarius theologiae Entered Order Licensed as Master Incepted Elected General Minister

1243-1253 1244 1254 1254 1257

1238-1245* 1238 1245 1248 1257

At least the two studies have one date in common, and with that one fixed date of 1257, we turn to examine the thirteenth and fourteenth century witnesses so as to dispel the disparity.

ii. exaMining the sources

Even though the dating for Bonaventures inception spans nine years, there are only seven sources that scholars can use to calculate those dates. More specifically, the majority of scholars support a 1253 or 1254 dating, with the year discrepancy likely deriving from how they calculate the dates in the sources according to medieval/modern calendars.13 Thus, to sort through the tangle of dating, all the evidence will first be presented in full. Then, in light of all the evidence, a scenario for dating Bonaventures inception can be advanced. The thirteenth and fourteenth century sources fall into four groups:14 (1) the Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam (c. 1283);15 (2) the two independent, short lists of General

13 For explanation of the different medieval calendars, see C. R. Cheney and Michael Jones, A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History, New Edition (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000), 4-5; also see Adriano Cappelli, Cronologia, cronografia e calendario perpetuo: Tavole cronografiche e quadri sinottici per verificare le date storiche dal principio dellEra Cristiana ai giorni nostri (Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1960), 8-11. 14 For a brief description of each of the sources see, Moorman, History, 292-94, and Bert Roest, Reading the Book of History: Intellectual Contexts and Educational Functions of Franciscan Historiography, 1226 - c. 1350 (Groningen: Regenboog, 1996), 36-39. 15 Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam, edited by Giuseppe Scalia, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 125, I-II (Turnhout: Bre-

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

183

Ministers: Series Magistrorum Generalium Ordinis Fratrum Minorum (c. 1261-64),16 and Chronicon Abbreviatum de Successione Generalium Ministrorum (c. 1304);17 (3) the three interdependent texts of the Catalogus Generalium Ministrorum,18 Catalogus XV Generalium (c. 1304; also called Catalogus Gonsalvinus),19 and the Chronica XXIV Generalium (c. 1360; also called Chronica Generalum Ministrorum),20 which contain significant variances from one another; and (4) the Chronica Franciscis Fabrianensis (c. 1322; also called Chronica Veneta).21 As will become clear, scholars who advance a 1248 date read Salimbene in light of Fabriano, while those who favor 1253 or 1254 read Salimbene in light of the Catalogus Generalium Ministrorum and related texts. Those who favor a 1257 dating, seem to ignore all these sources, and instead look to the Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis for evidence regarding when Bonaventure became a recognized regent master, which exceeds the scope of this paper.22 A. The Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam (c. 1283) Salimbenes witness provides four pieces of evidence. [John of Parma] hastened the end of the last general chapter that he presided over, because he no longer wished, by any means, to remain Minister General. This chapter was held in Rome, during the feast of the Purification in the year of the Lord 1257. And the

pols, 1998) hereafter abbreviated CCCM. English translation, The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, ed. Joseph Baird, et al. (New York: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1986). 16 Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptorum, 13, 392. Hereafter abbreviated MGH. 17 Tractatus Thomae Vulgo Dicti de Eccleston, De Adventu Fratrum Minorum in Angliam, ed. Andrew Little, in Collection dtudes et de documents sur lhistoire religieuse et littraire du Moyen ge, 7 (Paris: Fischbacher, 1909). 18 MGH, Scriptorum, 32, 664-65. 19 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897), 693-707. 20 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897), 1-575. 21 Giacinto Pagnani, Frammenti della Cronaca del B. Francesco Venimbeni da Fabriano, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 52 (1959): 15377. 22 See footnote 3.

184

Jay M. HaMMond

business of the chapter was completely stalled for one whole day because the Ministers, the Custodians, and the Delegates did not want to allow him to step down from his Office. Finally, Brother John went into the chapter meeting and made known his full desire according to his understanding of the situation. Then seeing the anguish of his spirit, those whose duty it was to see to elections, said to him, though against their will, Father, you have traveled throughout the Order and you know the ways of all the Brothers very well indeed; therefore, you select a suitable Brother to succeed you. And immediately he selected Brother Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, saying that he knew not a better man in the entire Order. And they all immediately agreed, and Bonaventure was elected. But they asked Brother John to continue to preside over this his last chapter, and it was so done. And Brother Bonaventure ruled for seventeen years and did many good works.23 1. The date of Bonaventures election as general minister: 2 February 1257 Salimbenes witness is explicit: Bonaventure was elected in 1257 on the feast of the Purification (2 February). Nota bene, Salimbenes dating follows the mode of the Nativity ac23 Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam, in CCCM 125, 473: Ultimum generale capitulum quod sub eo [John of Parma] celebratum fuit acceleravit, quia penitus nolebat esse minister; et factum est Rome, in festo Purificationis, anno Domini MCCLVII. Et steterunt per unum diem ministri et custodes et discreti, quod in negotiis capituli processum non est, quia penitus nolebant ipsum absolvere. Tunc ingressus locum capituli protulit verba sua secundum quod scivit et voluit dicere. Tunc hi quibus electio incumbebat, videntes angustiam anime eius, quamvis male libenter, dixerunt ei: Pater, vos, qui visitastis Ordinem et cognoscitis mores et conditiones fratrum, assignetis nobis unum ydoneum fratrem, quem constituamus super hoc opus, et vobis succedat. Et statim assignavit fratrem Bonaventuram de Bagnoreto et dixit quod in Ordine meliorem eo non cognoscebat. Et statim omnes consenserunt in eum, et fuit electus. Et rogaverunt fratrem Iohannem quod compleret capitulum. Et factum est ita. Et prefuit frater Bonaventura XVII annis et multa bona fecit. English translation, The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, ed. Joseph Baird, et al., 309.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

185

cording to the Pisan calendar (25 December 24 December), which basically corresponds with the modern calendar.24 2. The length of Bonaventures tenure as general minister: 17 years Salimbenes interval of seventeen years coordinates with Bonaventures election (1257) and death at the Council of Lyon (15 July 1274). Thus, the three dates of election, tenure, and death all triangulate. 3. The date John of Parma licensed Bonaventure: 1248 Brother John of Parma also gave Bonaventure of Bagnoreggio a license so that he could lecture at Paris, because he had never done it anywhere since he was a bachelor without a chair. And then, he gave a lecture on St. Lukes entire gospel, which is beautiful and best. And he wrote four books on the Sentences, which are useful and solemn up to the present day. Then it was the year 1248. Now, however, it is the year of the Lord 1284. Over time, he also wrote many other books, which are owned by many.25 In 1248 John of Parma licensed Bonaventure to lecture at Paris when he was only a bachelor and before he had a chair. The Quaracchi editors of the Opera omnia and Crowley claim that at this time Bonaventure must have been a formed bachelor (baccalareus formatus) because it would make no sense to say the Bonaventure was a mere bachelor without

Quinn, Chronology, 174-76. Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam, in CCCM 125, 458: Item frater Iohannes de Parma dedit licentiam fratri Bonaventure de Balneo Regis ut Parisius legeret; quod nunquam alicubi fecerat, quia bacellarius erat nec adhuc cathedratus. Et tunc fecit lecturam super totum Evangelium Luce, qua pulchra et optima est. Et super Sententias IIII libros fecit, qui usque in hodiernum diem utiles et sollemnes habentur. Currebat tunc annus millesimus CCXLVIII. Nunc autem agitur annus Domini MCCLXXXIIII. Fecit etiam processu temporis et alios multos libros, qui habentur a multis. English translation, The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, ed. Joseph Baird, et al., 299.

24 25

186

Jay M. HaMMond

a chair, which is obvious: an auditor theologiae would never hold a chair. However, there is another scenario that is not void of all meaning (omni sensu caret).26 Salimbenes comment suggests that what John of Parma did was out of the ordinary, that is, Bonaventure was given permission to lecture within the Franciscan convent even though he was not a master. Considering the circumstances of the context, the comment makes a great deal of sense. As Dufeil shows, the Franciscans at Paris maintained one public, external chair and one private, internal chair within the Franciscan studium, which the university did not officially recognize.27 Thus, in 1248 when Odo Rigaud leaves the public chair at Paris to become the archbishop of Rouen, William of Middleton steps up from the private chair to replace him as regent master, and John of Parma appoints Bonaventure, who was not yet a master, to lecture from the private chair. Such a scenario, which accounts for the organizational structure of the Franciscan studium, rejects the necessity for an early inception in 1248. 4. Bonaventures scholastic activities c. 1248. After being licensed, the record reports that Bonaventure then (ex tunc) lectured on the entire Gospel of St. Luke and (et) wrote his Sentences.28 Later university statutes claim that a bachelor was to lecture on Scripture for two years followed by two more years on the Sentences,29 but caution must be taken when applying statutes from 1335 and 1366 to explain

26

Opera omnia, vol. 10, 42-43; Crowley, Chronology Reappraisal,

318. Dufeil, Guillaume de Saint-Amour, 6-9; Bert Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 14, claims that the Franciscans had acting co-regent masters (magisteri in actibus) in the Franciscan studium. 28 Quinn, Chronology, 177, argues that the date of 1248 applies to when Bonaventure commenced the Commentary on Luke and cannot be used to determine when he started on the Sentences. However, the two Catalogi and the Chronica report that Bonaventure began the Sentences in 1251. See footnote 74 and related text. 29 Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis II, edited by Heinrich Denifle (Brussels: Culture et Civilisation, 1964), n. 1188.11, 692. Hereafter all references to the Chartularium are abbreviated CUP.

27

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

187

the practice of 1248: 87 to 118 years earlier.30 Nevertheless, it is important to note two points. First, by the 1240s it became standard practice for a Parisian baccalarius theologiae to lecture on Scripture and the Sentences.31 Second, nothing in Salimbenes mentioning of Bonaventures Luke commentary and four books on the Sentences conflicts with either the trends of the 1240s or with the later legislation of the 14th century. So if the later legislation represents an earlier tradition, a rather precise timeframe for Bonaventures studies can be determined: at least two years for the baccalarius biblicus, 1248-1250, followed by at least two years as baccalarius sententarius, 1250-1252.32 However, as will be shown,33 Bonaventure most likely lectured on Scripture for three years and the Sentences for two years. Ultimately, the precise sequential timeframe of Bonaventures studies takes back seat to the more relevant fact that he had six years to complete his lectures on Scripture and the Sentences, which

For descriptions of theological studies according to the later statues, see Palmon Glorieux, LEnseignement au Moyen ge: Techniques et mthodes en usage la facult de thologie de Paris au XIIIe sicle, Archives dhistoire doctrinale et littraire du moyen ge 43 (1968): 65-186; for more concise reviews, see Gordon Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1968), 164-71, especially 166, and Rashdall, The Universities of Europe, 474-79. 31 Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 123, comments that lectures on Scripture and the Sentences were formalized by c. 1250 in the Franciscan studium at Paris. Later he writes, By 1240, the Sentence commentary had established itself firmly in the Parisian theology faculty as a major element of higher theological education (125). On this point, also see Marie-Dominique Chenu, Matres et bacheliers de luniversit de Paris vers 1240, tudes dhistoire littraire et doctrinale du XIIIe sicle 1 (1932): 11-39. 32 As discussed below (see footnote 107 and related text), such a dating coordinates with Dufeils claim, Guillaume de Saint-Amour, 157-58, that the secular masters issued Quoniam in promotione to block Bonaventures reception into the consortium. Again caution is in order. According to Olga Weijers, Terminologie des universits au XIIIe sicle (Rome: Edizioni dellAteneo, 1987), 175-76, no 13th century university sources make the 14th century threefold distinction for the bachelor: baccalarius biblicus, sententiarius and formatus. For a description of the degree program in the 13th century at Paris, see Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 97-101; however, Roest bases much of his analysis on later legislation. 33 See footnote 74 and related text.

30

188

Jay M. HaMMond

is enough time for him to complete his studies before he replaced William of Middleton in 1254.34 A final point, Crowley also argues that a mere baccalarius biblicus could not have produced the Commentary on Luke.35 Such a comment overlooks one fact, glosses over another, and errs on a third. First, Crowley assumes that Bonaventure was a baccalarius who read as a cursus, restricted to giving only a cursory reading of the text.36 However, Bonaventure probably served as a lector biblicus.37 In the mendicant schools, the lector was in charge of the studium within the convent, and he was often studying theology at the same time he served as lector.38 This is precisely how the position and role of the lector evolved within the Franciscan Order.39 Significantly, the manifesto Excelsi dextra (1254) testifies to the position of the lectores among the regulars: We therefore decided to decree that no convent of the regulars in our college should have two, solemn chairs with acting regent masters teaching simultaneously, not meaning by this statute to prevent the friars from multiplying their own extraordinary lecturers as they might see fit.40 The evidence suggests that when John

34 See footnote 127 and related text. Since the two Catalogi and the Chronica report that Bonaventure read the Sentences in 1251, it is plausible that Bonaventure lectured on Scripture for three years not two. Of course not all his time had to be dedicated to the Luke Commentary. He may have also worked on his Commentarius in librum Sapientiae during the time. The Commentarius in librum Ecclesiastes and the Commentarius in Evangelium Ioannis both contain determinations, which indicate that he delivered those lectures as a master sometime after 1254. 35 Crowley, Chronology, 320, assumes that Salimbenes words qua pulcra et optima est seem better suited to the masterpiece of medieval exegesis in 1248, Commentarius in Evangelium S. Lucae, begun, at least, by Bonaventure in 1248, at the start of his career as Magister Regens 36 It is interesting that Crowley utilizes the same categories that he had just rejected, i.e., baccalarius biblicus, sententiarius and formatus. 37 Weijers, Terminologie, 160-63; also see Mariken Teeuwen, The Vocabulary of the Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages (Turnhout: Brepols, 2003), 85-87. 38 Weijers, Terminologie, 160-61. 39 Hilarin Felder, Geschichte der wissenschaftlichen Studien im Franziskanerorden bis um die Mitte des 13. Jahrhunderts (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1904), 325, 367, 373; and Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 81-97, especially 96, 100, and 105. 40 CUP I, n. 230, 254: Nos igiturprehabita duximus statuendum ut nullus regularium conventus in collegio nostro duas simul sollempnes ca-

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

189

of Parma licensed Bonaventure to lecture in 1248, he was not licensing him as a baccalarius biblicus, but as a lector biblicus who was above a cursus but below a magister.41 In effect, he granted Bonaventure the license as a bachelor so that he could lecture from the internal chair as William of Middletons assistant. In this capacity, Bonaventure would have been responsible for the non-degree lectorate program within the Franciscan studium at Paris,42 which constituted the majority of Franciscan students.43 Second, Crowley dismisses the fact that the Commentary on Luke does not determine, which was the privilege of a master.44 Rather than address this significant omission in the text, he simply rebuffs the suggestion that a non-master Bonaventure wrote the commentary by saying such a claim conflicts with the Quaracchi editors. He adds, The Commentary in its present state is undoubtedly the work of a master and not a beginner.45 But, as suggested, John did not license Bonaventure as a cursus or even as an apprentice lecturer (sublectores), but as a lector biblicus or lector extraordinarius or secundarius whose task it was to explore and elucidate the spiritual senses of Scripture.46 Third, Crowley asks, Is the Commentary in its present state a re-working of a Bachelors lectures? If it is, it is so skillfully done and so thorough that it defies detection. I can find no signs of re-vamping.47 However, manuscripts of the

thedras habere valeat actu regentium magistrorum, non intendentes per hoc statutum eos arctare quominus liceat eis inter fraters suos extraordinarios multiplicare sibi lectores, secundum quod sibi viderint expedire. For explanation of extraordinarius see Weijers, Terminologie, 306-10. 41 If the Epistola de sandaliis apostolorum (Opera omnia, vol. 8, 386a) is authentically Bonaventures, as Conrad Harkins argues (John Pecham and the Mendicant Controversy of the Thirteenth Century, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1973, 143-50), then we have at least one instance where Bonaventure called himself lector. The letter opens: Talis lector tali lectori spiritum intelligentiae sanioris. 42 Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 81-97. 43 Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 17 and 97. 44 Franz Pelster, Literargeschichtliche, 523. 45 Crowley, Chronology, 320. 46 Weijers, Terminologie, 306-10; Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 92. 47 Crowley, Chronology, 320.

190

Jay M. HaMMond

Luke Commentary actually preserve two forms of the text, which provides direct evidence that the commentary underwent stages of redaction: a later form represented in the Quaracchi edition and an earlier form corresponding more to the lectures of a bachelor.48 Thus, the lectures Bonaventure began in 1248 represent the earliest layer of the Luke Commentary and are most likely not the polished text that Salimbene praised as pulchra et optima.49 B. The Series Magistrorum Generalium Ordinis Fratrum Minorum (c. 1261-64) This list provides one piece of evidence, the date of Bonaventures election as general minister: 1257 Brother Crescentius took office in the year 1244 and served for three and a half years, being released from office in 1248. Brother John of Parma succeeded him. Brother John of Parma took office in the year 1248 and served for ten years. He was released from office in 1258 and was succeeded by Bonaventure. Brother Bonaventure took office in the year 1258, being elected as general in chapter on the Feast of the Purification (2 February). He is the seventh general minister.50

Bougerol, Introduction (1988), 179, also assumes that Bonaventure was a baccalarius biblicus. The earlier form is not simply a cursory reading of Luke, the later form accentuates the forma praedicandi. 49 Dominic Monti, Bonaventures Interpretation of Scripture in His Exegetical Works, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1979, argues for three stages of redaction after 1248: (1) 1254-1257 as regent master lecturing at Paris (154), 1260s as General Minister engaging Aristotles thought (54, n. 2), and (3) 1267-1268 as General Minister preaching the Sunday Sermons (155, n. 1). The redaction process would make Crowleys claim that a mere bachelor did not deliver the Commentary on Luke correct, but this fact would not support his interpretation of Bonaventures dating; rather it adds more evidence against it. 50 MGH, Scriptorum, 13, 392: Frater Crescencius cepit anno Domini 1244, et prefuit annis 3 et dimidium, et absolutus est anno Domini 1248, et ei successit frater Iohannes de Parma. Frater Iohannes de Parma cepit anno Domini 1248, et prefuit annis 10, et absolutus est anno Domini 1258, et ei successit Bonaventura. Frater Bonaventura cepit anno Domini 1258. Hic est septimus minister generalis par generale 25 capitulum electus in festo purificationis. English translation, Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, vol.

48

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

191

The fact that the title reads magistrorum rather than ministrorum probably indicates a non-Franciscan author, which may help explain the incorrect dating of when Cresentius left office (1247 not 1248),51 and when John of Parma was elected (again 1247 not 1248).52 That miscalculation results in Bonaventure being elected in 1258 not 1257.53 Yet the mention of his election on the Feast of the Purification (2 February) provides another witness that corroborates with other sources. C. The Chronicon Abbreviatum de Successione Generalium Ministrorum (c. 1304) This chronicle provides two pieces of evidence. After [John of Parma] was released from office, Bother Bonaventure of Bagnoregio was elected at the same chapter as the ninth general.54 He was a great doctor

3: The Prophet, ed. Regis Armstrong, J.A.Wayne Hellmann and William Short (New York: New City Press, 2001), 825. 51 The incorrect dating may also derive from the Chronica fratris Jordani, 76, which dates John of Parmas election to 1248, but this same source correctly dates the chapter of Rome to 1257, on the feast of the Purification. For the text, see Heinrich Boehmer, Chronica Fratris Jordani. Collection dtudes et de documents sur lhistoire littraire du moyen ge, 6 (Paris: Librairie Fischbacher, 1908), and Leonhard Lemmens, Continuatio et finis chronicae fratris Jordani de Jano, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 3 (1910): 47-54. English translation, XIIIth Century Chronicles, ed. Placid Hermann (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1961), 69. 52 For the correct date of John of Parmas election, see Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam, in CCCM 125, 473. English translation, The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, ed. Joseph Baird, 309. Also see Moorman, History, 589. 53 Since this source dates from c. 1261-1264 (marginal notes in the manuscript date it to the pontificate of Urban IV), it would be odd for a Franciscan source to miscalculate Bonaventures election date during his reign as minister. 54 Most of the other sources name Bonaventure as the seventh Minister General after Francis or as the eighth General when Francis is included in the list. This is the only witness that claims he was the ninth. To arrive at nine, Peregrine of Bologna must have included Peter Catani (vicar until 1221), whom Francis appointed after he abdicated in 1220, and Elias, whom Francis appointed after Peters death in 1221, in the count of ministers after Francis. In such a scenario, Elias is counted twice (vicar 1221-27 and general minister 1232-39).

192

Jay M. HaMMond

of theology and known by all. He held office for about sixteen years, and, having been made a Cardinal, was poisoned by a certain religious.55 As a consequence of this poison, he passed to the Lord.56 1. The date of Bonaventures election as general minister: 1257 On the one hand, this witness confirms that Bonaventure was elected at the same chapter that John of Parma was removed from office, which provides indirect support for a 2 February 1257 date. 2. The length of Bonaventures tenure as general minister: 16 years On the other hand, the witness also claims that Bonaventure held office for about sixteen years, which places his death in 1273, one year short of Bonaventures death on July 15, 1274. The Chronicle of the XXIV Generals corrects Peregrines witness: But the more common opinion holds that he ruled for 18 years or thereabout, because more than seventeen years were completed, in as much as it is from the Purification of Saint Mary up to Pentecost.57

55 This is the only source that mentions poisoning as the cause of Bonaventures death. Interestingly, while The Chronicle XXIV Generals certainly knew this source, the authors did not comment on this intriguing detail. 56 Tractatus Thomae Vulgo Dicti de Eccleston, De Adventu Fratrum Minorum in Angliam, ed. Andrew Little, in Collection detudes et de documents sur lhistoire religieuse et littraire du Moyen Age, 7 (Paris: Fischbacher, 1909), 144: Post eius absolutionem in eodem capitulo fuit electus nonus generalis frater Bonaventura de Balneoregio, et fuit magnus doctor in theologia, ut omnibus notum est. Qui stetit in officio fere per XVI annos, et, factus cardinalis, potionatus fuit a quodam religioso, de qua potione migravit ad dominum. English translation FA:ED 3, 829. 57 See footnote 62 and related text.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

193

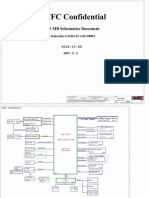

D. The Catalogus Generalium Ministrorum (c. 1304), Catalogus XIV vel XV Generalium (c. 1304), and Chronica XXIV Generalium (c. 1360) These three interrelated sources provide seven pieces of evidence. What follows is a compilation of the three sources. Bolded italic text represents variants from the two earlier Catalogi, the italicized text shows variants from the later Chronica, and the plain text is common to both. To allow for parallel comparison, Table 2 below presents the Latin from the three texts, which report: The most illustrious father, brother Bonaventure of Bagnoregio of the Province of Rome was the seventh to follow after St. Francis. [He] was made the eighth General, elected in the aforementioned chapter of Rome in the year after the incarnation of the Lord 1256, during the celebration of the Purification of Saint Mary. The lord Pope Alexander IV was present. When the General entered the Order as a youth, he was so endowed with the honor of good character, that the great master Alexander himself sometimes said that in him it seemed that Adam had not sinned It is a fact that in the seventh year after entering the Order he lectured on the Sentences at Paris, and in the tenth he received a magisterial chair, and in the twelfth or thirteenth he assumed control of the Order. He governed the Order for eighteen years, and in Lyon at the time of the general council, he died a cardinal at the age of 53, the bishop of Albano. Brother Bonaventure, before he was General, while he held the chair at Paris, defended the true gospel with the clearest disputations and determinations. The General brother Bonaventure, according to the chronicle of brother Peregrine of Bononia, ruled the Order for 16 years. But the more common opinion holds that he ruled for 18 years or thereabouts, because more than seventeen years were completed, in as much as it is from the Purification of Saint Mary up to Pentecost. When this brother [Bonaventure] was assumed to the cardinalate and at the time of the chap-

194

Jay M. HaMMond

ter during the general council of Lyon in 1274, the aforementioned brother Jerome was elected General minister, who was absent because he had not yet returned from being a legate. Table 2: Comparison of the two earlier Catalogues and the later Chronicle

Catalogue of the Catalogue of the 14 Chronicle of the 24 General Ministers or 15 Generals Generals

Septimus a beato Francisco successit praeclarissimus pater frater Bonaventura de Balneoregio. Septimus a beato Francisco successit praeclarissimus pater frater Bonaventura de Balneoregio. Octavus Generalis fuit praeclarissimus pater frater Bonaventura de Balneregio Provinciae Romanae, electus in praedicto capitulo Romae anno ab incarnatione Domini MCCLVI, in festo Purificationis beatae Mariae celebrato, domino Alexandro Papa IV praesente Qui Generalis, cum iuvenis intrasset Ordinem, tanta bonae indolis honestate pollebat, ut magnus ille magister Alexander de Alis disceret aliquando de ipso, quod videbatur Adam in eo non peccasse Hinc factum est, ut in VII anno post ingressum Ordinis Sententias Parisius legeret et in X reciperet cathedram magistralem; in XII vero vel XIII ad regimen Ordinis est assumptus

Qui cum iuvenis intrasset ordinem, tanta bone indolis honestate pollebat, ut magnus ille magister frater Alexander diceret aliquando de ipso, quod in eo videbatur Adam non peccasse Hinc factum est, ut in septimo anno post ingressum ordinis Sententias Parisius legeret et in decimo reciperet cathedram magistralem, et in XII vel XIII ad regimen Ordinis est assumptus.

Qui cum iuvenis intrasset Ordinem, tanta bonae indolis honestate pollebat, ut magnus ille magister Alexander diceret aliquando de ipso, quod in eo videbatur Adam non peccasse ... Hinc factum est, ut in septimo anno post ingressum Ordinis Sententias legeret Parisius et in decimo reciperet cathedram magistralem et in XII vel XIII ad regimen Ordinis est assumptus.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

195

Decem et octo annis rexit Ordinem et in Lugduno tempore generalis concilii obiit cardinalis anno etatis suae LIII, episcopus scilicet Albanensis. Hic antequam esset minister, dum teneret Parisius cathedram, veritatem evangelicam clarissimis disputationibus et determinationibus defensavit.58 Hoc patre ad cardinalatum assumpto et tempore concilii generali capitulo Lugduni congregato 1274, frater Ieronimus predictus absens, quia nondum a legatione redierat, in generalem ministrum ellectus est59

58

Decem et octo annis rexit Ordinem et in Lugduno tempore generalis concilii obiit Cardinalis, anno aetatis suae LIII, episcopus scilicet Albanensis Hic antequam esset Minister, dum teneret Parisius cathedram, veritatem evangelicam clarissimis disputationibus et determinationibus defensavit.60 Hoc fratre ad cardinalatum assumpto et tempore concilii generalis capitulo Lugduni congregato 1274, frater Hieronymus praedictus absens, quia nondum a legatione redierat, in Generalem Ministrum ellectus est.61

Hic Generalis frater Bonaventura secundum chronicam fratris Peregrini de Bononia rexit Ordinem XVI annis vel circa. Sed communior opinio tenet, quod rexit XVIII annis vel circa, quia XVII annis completis et ultra, qantum est a Purificatione beatae Mariae usque ad Pentecosten.62 Iste frater Bonaventura, antequam esset Generalis, dum teneret Parisius cathedram, veritatem evangelicam clarissimis disputationibus et determinationibus defensavit.63

MGH, Scriptorum 32, 664-65. MGH, Scriptorum 32, 666. 60 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897):600. 61 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897): 701. 62 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897): 354. 63 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897): 323-26.

59

196

Jay M. HaMMond

1. Bonaventures place in the succession of general ministers: 7th or 8th The discrepancy between the two earlier Catalogi and the later Chronica is easily explained. The former identify Bonaventure as the seventh Minister General after Francis while the latter includes Francis in the list, which makes Bonaventure the eighth General Minister. 2. The year Bonaventure was elected general minister: 2 February 1257 Of the three sources, only the Chronica provides an explicit date for Bonaventures election, 1256 on the feast of Marys Purification (2 February); but the two Catalogi provide indirect evidence because both mention that Bonaventure ruled for eighteen years (i.e., 1256-1274).64 Nota bene, all three witnesses follow the mode of the Incarnation according to the Florentine calendar (25 March to 24 March), which corresponds to 1257 on a modern calendar.65 Moreover, all three sources recognize the variance between the Pisan and Florentine calendars when they report that Bonaventure was elected in the twelfth or thirteenth year after joining the Order: according to the Florentine calendar, he was elected in the twelfth year, but, according to the Pisan calendar, he was elected in the thirteenth year. This vital point is highlighted by the fact that the Chronicle of the XXIV Generals, in correcting the dating of Peregrine of Bolognas Chronica,66claims Bonaventure ruled for eighteen years if one calculates according to the Florentine mode, but only seventeen years according to the Pisan mode. The year of Bonaventures election is most important because only by identifying this date can the other calculations from these three sources be determined. 3. The year Bonaventure entered the Order: 1244 Much of the confusion over when Bonaventure entered the Order derives from the dual dating contained in these three sources. Table 3 illustrates the problem.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

197

Table 3: Possible dates derived from the dual dating of twelve or thirteen years 12 years 1256 1257 1244 1245 13 years 1243 1244

Unfortunately, modern studies have advanced all three dates as possibilities (1243-1245).67 Since the previous section established 1257 as the date of Bonaventures election, all three witnesses, calculated according to the Florentine calendar, produce a date of 1243, which corresponds to 1244 in the modern mode.68 The dual dating actually corroborates a 1244 date because, as Table 3 shows, only 1244 can accommodate a twelve or thirteen year calculation.69 Determining the correct date for Bonaventures entry into the Order is most crucial because all three sources calculate other key events post ingressum ordinis. They all also mention that Bonaventure entered the Order as an iuvenis.70 The evidence suggests that Bonaventure was twenty-three at the time he entered the Order or twenty-two if one includes his one year novitiate. Since Francis Fabriano reports that Bonaventure completed his Arts degree before

67 For example, Callebaut, Lentre de S. Bonaventure, 42, and Abate, Per la storia e la cronologia, 100, give 1243, while Pelster, Literargeschichtliche, 517, has 1244 or 1245. Later studies fare no better, Brady, Bonaventure, St., 658b, and Hammond, Bonaventure, St., 479a, both have 1243, but Quinn, Chronology, 186, gives 1244. The dating is complicated even more by the fact that Crowley, Chronology, 322, holds for a 1238 dating. 68 See footnote 65 and related text; also see Quinn, Chronology, 176. 69 Quinn, Chronology, 176. 70 Crowley, Chronology, 311-13, belabors the point that Bonaventure was a youth (iuvenis) even though he admits that it is an elastic term applying to anyone over 15 and under 40. If Bonaventure was 23 when he entered the Order, that age certainly qualifies for the name iuvenis. According to Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 91, a student beginning his theological studies at Paris would have been around 21 to 23 years old. The Constitutions of Narbonne list 18 as the normal cut-off for entry into the Order, allowing for those 15 and older in extraordinary cases (Opera omnia, vol. 8, 450b).

198

Jay M. HaMMond

joining the Order,71 Bonaventure, if he followed the University statutes,72 likely began studying the Arts in 1235 and must have been at least twenty in 1241.73 Such a chronology coordinates with when Bonaventure became a novice and then professed: born 1221, studies Arts 1235-1241, lectures on the Arts 1241-1243, novitiate 1243, and profession 1244. 4. The year Bonaventure read the Sentences: 1251 All three sources report that in the seventh year Bonaventure read the Sentences at Paris. Thus, if he entered the Order in 1244, Bonaventure read the Sentences in 1251. There is no mention of a timeframe, so more specificity is not possible. However, a 1251 date can coordinate with Salimbene and allows Bonaventure time to complete the Sentences before 1254.74 Thus, he most likely lectured on Scripture for three years (1248-1251) and the Sentences for two years (1252-1253). 5. The year Bonaventure received his magisterial chair: 1254 All three sources forthrightly report that Bonaventure became a master and received a chair at Paris in 1254. Corroborating evidence comes from the Chronicas report of John of Parmas activities in 1254. Therein, the witness records: In the year of our Lord 1254 also at the time brother Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, the strongest defender of truth for the mendicant religion, gained the magisterial

See footnote 90 and related text. CUP I, n. 20, 78. Robert Curzons statute from 1215 states three things: (1) a student must be an auditor for six years, (2) he must lecture for two years, and (3) he must be at least twenty to lecture. Thus, the Arts degree lasted for eight years. 73 CUP I, n. 20, 78 reads, No one may lecture in the arts at Paris before his twenty-first year (Nullus legat Parisius de artibus citra vicesimum primum aetatis suae annum), meaning that the lecturer has to be at least twenty. On this point see, Rashdall, The Universities of Europe, 462, n. 4. 74 See footnote 28 and related text.

71 72

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

199

chair at Paris. Also in the year 1254 75 The date of 1254 reveals two things. First, since the Chronica follows the Florentine mode,76 the inception had to have occurred after 25 March.77 Second, it is clear that the witness means 1254 in the modern mode because the occurrence of Eodem anno MCCLIIII records the death of Innocent IV and the election of Alexander IV in December 1254. In effect, the witness sandwiches the inception between two other 1254 events that can be externally verified. Therefore, the inception occurred sometime after 25 March of 1254, probably around Easter, which was on 12 April. 6. Bonaventures age when he died: 53; born 1221 Significantly the first two Catalogi state that Bonaventure died at the age of 53, but the later Chronica omits this important detail. The omission is all the more obvious when one considers that the Chronica incorporates, virtually verbatim, all the data from the earlier two sources. Why the omission? Abate may provide an answer. He argues that Bonaventure had to be at least 40 in 1257 because the Constitutiones Urbanae (1628), following the earlier tradition, stipulate that a general minister had to be over 40 and under 70.78 Yet, the omission suggests that by c. 1360 generals had to be 40, but c. 1304 it was not yet a regulation. Thus, the Chronica removes the data that conflicts with the current practice at the time the Chronica was written. The fact that Bonaventure did not have to be 40 is supported by the simple fact that John of Parma was only 38 or 39 when elected.79 Hence, Abates evidence for a 1217 date for Bonaventures birth, actually supports a 1221 date, which does not require

75 Analecta franciscana 3 (1897), 277-78: Anno vero Domini MCCLIV Eodem tempore frater Bonaventura de Balneregio, pro Religiosis Mendicantibus defensor fortissimus veritatis, Parisius assecutus est cathedram Magistralem. Eodem anno MCCLIIII 76 See footnote 65 and related text. 77 Quinn, Chronology, 186, n. 44.

200

Jay M. HaMMond

the age of Bonaventures death to be changed from LIII to LVI to make the dates coordinate.80 Abate also argues that Bonaventure had to be at least 35 at the time of his inception to fulfill the 1215 statute of Robert Curzon.81 This would require Bonaventure to be born in 1219. However, considering the circumstances surrounding Bonaventures inception as master, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the University faculty chose not to enforce the statute so Bonaventure could incept at thirty-three. With this rather small allowance, they would gain a great deal: removal of William and any Franciscan claim to two chairs. Moreover, it is clear that Thomas Aquinas incepted two years later even though he was not 35.82 Hence, it is not morally certain that St. Bonaventure was born no later than 1217 because the evidence supports a 1221 dating.83 7. The length of Bonaventures tenure as general minister: 18 years All three sources report that Bonaventure served as general for eighteen years. The Chronica, clarifies the date according to the Florentine mode of the Incarnation: But the more common opinion holds that he ruled for 18 years or thereabout, because more than seventeen years were completed, in as much as it is from the Purification of Saint Mary up to Pentecost.84 Since the Florentine calendar changed years on 25 March, Bonaventure served for 18 years (2 Feb 1257 to 15 July 1274) because seventeen years plus the time between 2 February to 25 March makes eighteen years, which is the point the Chronica tries to clarify.

80 Abate, Per la storia e la cronologia, 107, n. 1, changes the date to make his chronology synchronize. 81 CUP I, n. 20, 79. 82 CUP I, n. 270, 307. Jean-Pierre Torrell, Saint Thomas Aquinas, vol. I (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1996), 5051, comments that Thomas was only thirty-one or thirty-two 83 Quinn, Chronology, 173. In light of the evidence, I must again correct my own earlier dating in the New Catholic Encyclopedia, Second Edition (2002), 479a, which gives a 1217 date. 84 See footnote 62 and related text.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

201

E. The Chronica Franciscis Fabrianensis (c. 1322) This chronicle provides five pieces of evidence. The seventh General Minister after the death of our Saint Francis was Brother Bonaventure of Bagnoreggio, a man of good memory, holy and just, and righteous and God fearing, completed (consummatus) the arts among the Parisians, and made (effectus) master in sacred theology after entering himself into the Order, licensed (licentiatus) under master Alexander, first master of the Order, whom, when in time, all the University of Paris followed, under whom seven of our brothers were licensed and made (effecti) Masters in sacred theology. Now it is said that Bonaventure was a most eloquent man, with an exceptional understanding of sacred Scripture and all of theology, a beautiful homilist to clerics and preacher to the people, in whose presence every language of every land was silent. He was made general minister 33 years after Saint Francis. He was general for 15 years and, while remaining general, was made Cardinal by the lord Pope Gregory X at the council of Lyon.85

Fabriano Ms. 117, 50v. Giacinto Pagnani, Frammenti della Cronaca del B. Francesco Venimbeni da Fabriano, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 52 (1959): 172, cited below as P and Crowley, Chronology, 317, cited below as C: Septimus Generalis Minister post transitum beati Patris nostri Francisci fuit frater Bonaventura de Bagnoleo, vir bonae memoriae [P comma; C no comma] sanctus et iustus, et rectus ac timens Deum [P comma; C no comma] consummatus in artibus apud Parisios et post ingressum ipsius in Ordnem Magister effectus [C comma; P no comma] in sacra Theologia [P comma; C no comma] Licentiatus sub Magistro Alexandro, primo Magistro Ordinis, quem cum esset in saeculo tota Parisiensis Universitas sequebatur, sub quo septem Fratres nostri fuerunt licentiate et Magistri effecti in sacra Theologia. Hic iam dictus frater Bonaventura vir eloquentissimus fuit, mirabilis intellectu sacrae Scripturae et totius sacrae theologiae, pulcherrimus sermocinator ad clerum et praedicator ad populum, in cuius praesentia ubique terrarium omnis lingua silebat. Hic factus est generalis Minister xxxiij anno a transitu beati Francisci. Hic stetit Generalis xv annis et, existens Generalis, factus fuit Cardinalis a domino papa Gregorio decimo in concilio Lu[g]dunensi.

85

202

Jay M. HaMMond

1. Bonaventures place in the succession of general ministers: 7th Like the two Catalogi, Fabriano does not include Francis when calculating Bonaventures number as general minister. He is the seventh after Francis. 2. The date of Bonaventures election as general minister: 1259 This is the first signal that Francis Fabrianos Chronica may be an untrustworthy witness.86 He reports that Bonaventure became general minister thirty-three years after Saint Francis, and served as general for 15 years. The numbers add up, but provide the wrong date for Bonaventures election because, although Fabriano correctly identifies Franciss death on 4 October 1226,87 the thirty-three year interval dates his election to 1259. The mistake is compounded by the fact that the fifteen year interval of service coincides with the date of Bonaventures death in 1274. Nota bene, Fabriano miscalculates by three years according to the Florentine calendar and two years according to the Pisan calendar, neither of which can be fixed by alternative dating via different modes of medieval calendars. All the other sources give 1257 for Bonaventures election. This witness alone gives a 1259 date.88 Thus, Francis Fabrianos evidence regarding Bonaventures election date should be rejected.

86 Nowhere does Crowley, Chronology, acknowledge the error, likely because it undermines Francis Fabriano as a reliable witness, and since Crowley builds his entire argument upon it, if it is untenable, so too is Crowleys interpretation. 87 Pagnani, Frammenti della Cronaca, 169. 88 It is particularly odd that Crowley, who depends so heavily of Franciss report, claims that Bonaventure, with absolute certainty, was elected in 1257 (Chronology, 310, 322). He simply ignores the errors of his favored witness.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

203

3. The sequence of Bonaventures studies: completed arts, entered Order, became master I keep the Latin in the above translation to highlight how it conveys the flow of Bonaventures studies: consummatus in the arts before entering the Order, effectus as master after he entered, and licentiatus by Alexander. The flow is important because Crowley argues that a comma should be placed after magister effectus instead of in sacra Theologia so as to read the text as meaning Bonaventure became a master of the Arts rather than a master of sacred theology. He asserts, When placed after the word effectus, the text loses its slovenly, unrhythmical appearance; it acquires balance, becomes natural and respectful of orderly sequence.89 I beg to differ. Note the alternative readings: Crowley: consummatus in artibus apud Parisios et post ingressum ipsius in Ordnem Magister effectus, in sacra Theologia Licentiatus sub Magistro Alexandro.90 Pagnani: consummatus in artibus apud Parisios et post ingressum ipsius in Ordnem Magister effectus in sacra Theologia, Licentiatus sub Magistro Alexandro.91 The first has consummatus and effectus within the same clause and ignores the conceptual break of et post. In effect, Crowley argues that the text only reports two events: one involving the arts, the other involving licensing. The second separates into three clauses by recognizing the division of et post. Here the text reports three events: consummatus arts, effectus master, and licentiatus Alexander.92 The three past participles neatly structure the sentence and provide an orderly sequence. Moreover, the comma placement after sacra Theologia becomes even more obvious when one notices the exact same construction just a few lines down, sub quo sepCrowley, Chronology, 314-15. Crowley, Chronology, 317. 91 Pagnani, Frammenti della Cronaca, 172. 92 For consideration of licentiatus as technical term referring to a licensed student or scholar, see Teeuwen, Vocabulary, 91.

89 90

204

Jay M. HaMMond

tem Fratres nostri fuerunt licentiate et Magistri effecti in sacra Theologia. Even though Crowley cites the expanded text five times in his footnotes, he ignores this second occurrence of Magistri effecti when constructing his argument.93 Even more problematic is that Crowley, like Abate, alters dates to synchronize Francis Fabriano with the two Catalogi and the Chronica. Following the Quaracchi editors,94 he solves the major difficulty by inserting a V into XII or XIII, which he claims should actually read XVII or XVIII.95 Without any evidence whatsoever, Crowley adds five years to make his chronology compatible. He concedes, it seems to be the only way to reconcile the data at our disposal.96 But in fact, there is an easier explanation: the witness is wrong. Thus, little trustworthy evidence can be gleaned from the Chronica Franciscis Fabrianensis (c. 1322). It does add a corroborating witness that Bonaventure was the seventh general minister after Francis, the plausible claim that he finished his Arts studies before entering the Order, and the basic fact that he became a master in theology; but the remaining evidence can not sequence with the other 13th and 14th century witnesses. Thus, it should be judged inaccurate, and Crowleys interpretation of it discarded.97 4. The date Alexander of Hales licensed Bonaventure: 1245 or earlier Since Alexander of Hales died on 21 August 1245, he would have had to license Bonaventure before this date. Since Fabriano mentions seven other brothers who were licensed and made masters in sacred theology under Alexander, it

Crowley, Chronology, 314-15. Opera omnia, vol. 10, 47-48. 95 Crowley, Chronology, 321-22. 96 Crowley, Chronology, 322. 97 This is particularly unfortunate considering other scholars construct their arguments upon the foundation of Crowleys chronology. For example, Michael Cusato, Esse ergo mitem et humilem corde, hoc est esse vere fratrem minorum: Bonaventure of Bagnoregio and the Reformulation of the Franciscan Charism, in Charisma und religise Gemeinschaften im Mittelalter, ed. Giancarlo Andenna, Mirko Breitenstein and Gert Melville (Mnster: LIT, 2005), 343-82, especially 356ff.

93 94

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

205

is safe to assume the same applies to Bonaventure, i.e., the testimony refers to his terminal licensing and not an earlier, intermediate one, e.g., as a bachelor. However, this is in direct contradiction with Salimbene who reports that Bonaventure was still a bachelor in 1248,98 and the Catalogi/Chronica that state 1254 for Bonaventures inception. Given the other problems with Fabrianos witness, the other sources, which do not conflict with each other, seem to be more reliable. Bonaventure undoubtedly studied under Alexander, but he was not licensed by him in the capacity Fabriano indicates. 5. The length of Bonaventures tenure as general minister: 15 years Fabriano is the only witness to claim Bonaventure served as general for fifteen years. As mentioned above,99 it seems that he may have determined this increment to coincide with Bonaventures death in 1274. Regardless of the reason, the dating is wrong and cannot be corrected by appeal to differing medieval calendar calculations. Thus, this piece of evidence should also be rejected.

suMMary of part i

These seven sources provide the following pieces of evidence: 1221 1235-41 1241-43 1243 Bonaventures birth Studies the Arts at 14 Lectures on the Arts as a bachelor at 20 Master of Arts, enters novitiate; begins status as auditor theologiae100 at 23

See footnote 25 and related text. See footnote 86 and related text. 100 CUP I, n. 20, 80, stipulates that a student had to be an auditor for five years; thus, if Bonaventure began his theology studies in 1243, he would have completed the requirement before he was licensed by John of Parma in 1248. However, the later legislation from Narbonne 1.8 prohibits a novice from studies during the whole time of their probation. Thus, even though it is not entirely clear whether Bonaventure became an auditor in

98 99

206

Jay M. HaMMond

1244 1248 1248-51 1252-53 1253 1254 1257

Profession, officially enters the Order at 24 Licensed lector biblicus by John of Parma at 27 Baccalarius biblicus Baccalarius sententiarius Baccalarius formatus Incepts as master to replace William of Middleton at 33 Elected General Minister at 35 (36 if born before 2 February)

iii. Bonaventures chronology, 1221-1254

Having established the evidence in the previous section, the analysis now turns to provide a narrative treatment of Bonaventures chronology. Bonaventure began his study of the Arts in 1235. Following normal university procedure, he was an auditor for four years, and then lectured for two years (1241-1243).101 Upon becoming a Master in the Arts, he entered the Franciscan Order as a novice in 1243, and continued his studies as a baccalarius theologiae under Alexander of Hales. Significantly, Bonaventures religious vocation marked the next step of his academic journey. Following the year novitiate, he formally entered the Franciscan Order in 1244, and, after completing the standard five years as auditor theologiae,102 John of Parma licensed him to teach in 1248. The license enabled Bonaventure to occupy the Franciscan private chair, which was vacated by William of Middleton who moved to the public chair to replace Odo Rigaud who left Paris to serve as archbishop of Rouen. As lector of the private chair, Bonaventure helped direct the lectorate program in the Franciscan studium, while he continued his own studies. He was a baccalarius biblicus for three years (1248-1251) and a baccalarius sententiarius for two (1252-

1243 or 1244, based on the context of the 1240s, I posit a 1243 date; Quinn, Chronology, 178, 186, concurs. 101 See footnote 72 and related text. 102 See footnote 100 and related text.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

207

1253). Yet by 1250, the fragile truce between seculars and mendicants had fractured. Although there was previous acrimony between the seculars and mendicants at the University of Paris,103 the controversy of the 1250s started anew when Innocent IV instructed the Chancellor of Paris to license all qualified students, especially those belonging to religious orders; even if they had not requested a license.104 In response, the seculars at Paris issued Quoniam in promotione on February 1252, which declared that: (1) no regular could be admitted to the consortium magistrorum without affiliation with a studium at Paris; (2) every religious order could only have one chair and one school; and (3) no religious bachelor could become a master unless they had studied at a recognized studium and lectured under the supervision of a regent master recognized by the seculars.105 With the statute, the seculars tried to deprive the Dominicans of one of their chairs and to ensure that the Franciscans could never gain a second.106 In 1253, Bonaventure likely finished lecturing on the Sentences and became a formed bachelor (baccalaureaus formatus), but his inception would have been blocked for two reciprocal reasons: the seculars opposition embodied in Quoniam in promotione,107 and the fact that the Franciscan

103 Andrew Traver, Rewriting History? The Parisian Secular Masters Apologia of 1254, History of Universities 15 (1997-99), 10-12, lists four: the great dispersion of 1229, the question of pluralism in the 1230s, the 1237 issue of who and how the licentia docendi was to be granted, and the condemnations of both Franciscan and Dominican preachers in the early 1240s. 104 CUP, n. 191, 219. For the narrative that follows, see Palmon Glorieux, Le conflict de 1252-7 la lumire du mmoire de Guillaume de St. Amour, in Recherches de Thologie ancienne et mdivale 24 (1957): 36472; Rashdall, The Universities of Europe, 376-91; Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities, 34-44; Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 53-55. 105 CUP, n. 200, 226-27. 106 Traver, Rewriting History? 12. 107 The last two restrictions would have prevented Bonaventure from incepting once he became a Baccalarius formatus in 1253. Dufeil, Guillaume de Saint-Amour, 157-58 actually argues that the secular masters produced this legislation, at least in part, to block Bonaventures entrance into the consortium magistorum because they did not want the Franciscans, like the Dominicans, to attain a second public regency. Also see Rash-dall, Universities, 376-77; Roest, A History of Franciscan Education, 54.

208

Jay M. HaMMond

chair was already occupied by William of Middleton. Thus, Bonaventure simply kept lecturing from the private chair within the Franciscan studium. The situation took a drastic turn following the riotous Lenten festivities in March 1253 during which a student was killed.108 While seeking restitution for the crime, the University announced a cessation of all lectures,109 but three religious (two Dominicans and William of Middleton) continued lecturing. In retaliation against the defiant mendicants, the seculars wrote Nos universitas in April (promulgated 2 September),110 which stipulated that all masters of the consortium must swear an oath to observe the University statutes. After fifteen days, anyone who had not adhered to the statute would be excommunicated and expelled from the consortium.111 The Dominicans agreed to the statute, but only on the condition that their two chairs be perpetually preserved.112 The seculars refused to cede because such a concession would have directly undermined Quoniam in promotione. Once the University resumed lectures after a seven week hiatus, the seculars issued an edict of separation against the three regulars and began the formal process of excommunication.113 The mendicants appealed to the pope. In July, Innocent IV entered the fray by issuing three letters in support of the regular cause. First, Amena flora (1 July), ordered the seculars to readmit the three mendicant masters into the university consortium until the pope could hear the case himself;114 the seculars refused. Transmissa nobis (21 July) followed, which absolved the three excommu-

108 Both Excelsi dextera (CUP I, n. 230, 254) and Quasi lignum vitae (CUP I, n. 247, 280) mention the event; also see Rashdall, The Universities of Europe, 376-83. 109 CUP I, n. 219, 242; also see Excelsi dextera (CUP I, n. 230, 254) and Quasi lignum vitae (CUP I, n. 247, 280), which both mention the event. The power of cessatio was granted in 1231 by Gregory IXs Parens scientiarum (CUP I, n. 79, 136-39). 110 CUP I, n. 219, 242-44. 111 On the issue of the Universitys power to excommunicate, see Traver, Rewriting History? 36, n. 37. 112 CUP I, n. 230, 254-55. 113 See CUP I, n. 224, 248 and n. 230, 255. 114 CUP I, n. 222, 247.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

209

nications against the regulars.115 The final decree, Excelsi dextera (26 August), which explicitly mentions the Dominicans and Franciscans, warned the seculars not to promulgate Nos universitas before 15 August 1254, which would allow time for the pope to mediate the dispute. Accordingly, the pope sent a delegation to Paris to arbitrate the controversy. However, likely unaware of the popes warning, the seculars officially released Nos universitas less than a week later on 2 September. The statute upheld the expulsion of the three mendicant masters and placed the Dominicans and Franciscans under more stringent university control before the start of the Michaelmas term of 1253.116 Significantly, the statute focused its attention on the inception of new masters: no master may presume to hold a principium for any bachelor or to be present at his principium unless it were first clear to him that the same bachelor had been bound to the aforementioned [oath] in the usual way. Furthermore, a bachelor would in no way be accepted by us as a master if he incepted in another way.117 Nos universitas was the last document, issued by either the seculars or the pope, including his legates, that will mention the Franciscans until almost three years later, with the decree of Licet olim (27 June 1256) delivered at Anagni during the condemnation of William of Saint-Amour.118 The ensuing silence from the seculars regarding the Franciscans after September 1253 suggests that reconciliation

CUP I, n. 224, 248. According to the seculars own witness, as reported in Excelsi dextera (CUP I, n. 230, 252-58), this is the last time that the seculars mention the Franciscans as disrupting the authority of the consortium. Thus sometime after this date and before 4 February 1254, John of Parma had reconciled with the seculars. On this point see footnote 120 and related text. 117 CUP, n. 219, 243: nullus magister principium alicujus bachelarii tenere vel ejus principio interesse presumat, nisi prius ei constiterit, quod idem bachelarius ad predicta modo prehabito sit ligatus. Nec idem bachelarius, si alio modo inceperit, magister a nobis aliquatenus habeatur. 118 CUP I, n. 281, 323-24.

115 116

210

Jay M. HaMMond

was achieved. Thus, the seculars would not have protested against Bonaventures principium as long as he abided by the stipulations of Nos universitas. The silence implies that Bonaventure did. The mendicant response to Nos universitas was twofold: one Dominican, one Franciscan. On the one hand, the Dominicans continued their fight against the University.119 On the other, the Franciscans reconciled with their secular colleagues sometime after 2 September 1253 (Nos universitas) and before 4 February 1254 (Excelsi dextera).120 Both Thomas of Eccleston and Salimbene report that John of Parma traveled to Paris and delivered a reconciliatory sermon before the University. Eccleston reports: He quieted the unrest of the brothers at Paris by personally reminding them at the university of the simplicity of their profession and prevailed upon them to revoke their appeal.121 The mention of an appeal suggests that the Franciscans may have been attempting to acquire two public chairs like their Dominican counterparts.122 Salimbenes report is more substantial. After recounting the allegory of the King planting a noble plant in his garden, Salimbene reports that John explained the allegory (the King: God the Father, the plant: the learning of the Paris faculty, and the garden: the lesser brothers of Francis), and then humbly pronounced before the entire university faculty:

119 The secular manifesto Excelsi dextera of 4 February 1254 even claims that the Dominicans rebelled against the University (CUP, n. 230, 256-57), but this must be interpreted prudently because it is reported by the seculars. 120 See footnote 144 and related text. 121 Thomas of Eccleston, Tractatus de Adventu Fratrum Minorem in Angliam, Analecta Franciscana 1 (1885), 244: Ipse frater Parisius personaliter in Universitate, professionis simplicitatem protestans, revocata appellatione quam facerant, reconciliavit. The Tractatus was later reedited by Andrew Little, Fratris Thomae Vulgo Dicti de Eccleston Tractatus de Adventu Fratrum Minorum in Angliam (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1951), 92. English translation, Placid Hermann, XIIIth Century Chronicles (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1961), 160-61. 122 Dufeil, Guillaume de Saint-Amour, 158.

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

211

Although I am unworthy and I serve against my own will, I am Minister General of the Lesser Brothers. You are our lords and our masters; we, your servants, sons, and disciples. And if we have any learning, we wish to acknowledge that it has come from you. I place myself and the Brothers who are under my rule under your discipline and correction. Behold, We are in your hands: deal with us as it seem good and right unto you.123 When they heard these things, they were all satisfied, and their spirit was quieted, which had swelled against124 the brothers.125 John of Parmas willingness to place the Franciscans under the discipline and correction of the University suggests that the Franciscans agreed to abide by the academic regulations of the faculty, which remained the fracture between the Dominicans and the seculars as outlined in Excelsi dextera.126 Thus, the secular-Franciscan reconciliation likely involved: (1) agreement by the Franciscans, in accordance with Quoniam in promotione, to hold only one chair; (2) observance of Nos universitas, binding the Franciscan regent master to obey University statutes; and (3) the removal of William of Middleton as regent master.127 If the

Joshua 9:25. Judges 8:3. 125 Chronica fratris Salimbene de Adam, in CCCM 125, 459: Ego sum generalis minister Ordinis fratrum Minorum, quamvis insufficiens et indignus et contra voluntatem meam, vos estis domini et magistri nostri, nos vero servi vestri, filii et discipuli; et si aliquam scientiam habemus, a vobis volumus cognoscere nos habere. Expono memet ipsum et fratres qui sunt sub manu mea discipline et correctioni vestre. Ecce in manibus vestris sumus. Facite de nobis quod rectum et bonum vobis videtur. Audientes hoc omnes acceperunt satisfactionem, et quievit spiritus eorum, quo tumescebant contra fratres. English translation, The Chronicle of Salimbene de Adam, ed. Joseph Baird, 299-300. 126 See Quinn, Chronology, 179-80, and Rashdall, The Universities of Europe, 383, n. 4. 127 Most likely William remained in Paris, occupying the private chair in the Franciscan studium. It is clear that he was in Paris in the summer of 1255 when Alexander IV commissioned him to complete the Summa fratris (CUP I, n. 286, 328-29). The CUP dating of 28 July 1256 is incorrect. The critical edition of the Bull, found in Summa Theologica, ed. PP. Collegii S. Bonaventurae, vol. 1 (Quaracchi: Collegium S. Bonaventu123 124

212

Jay M. HaMMond

compromise brokered by John of Parma required William to step down, then William and Bonaventure, who was already licensed by John in 1248 to lecture from the private chair, likely swapped their chairs, that is, Bonaventure ascended to the public chair recognized by the university while William, expelled from consortium magistrorum by the secular masters,128 remained in Paris occupying the private chair within the Franciscan studium.129 The compromise necessitated Bonaventures inception before he could officially begin serving as regent master. Moreover, it can be inferred that his forthcoming principium adhered to the aforementioned stipulations regarding principia as outlined in Nos universitas;130 otherwise, the seculars would have branded his inception as illegitimate. In effect, far from opposing Bonaventures inception, the compromise suggests that the seculars would have likely supported his inception because it appeased their ire against William of Middleton, capped the Franciscan chair at one, and ensured that the new regent, as part of his principium, would swear to obey any new statutes issued by the faculty. The compromise likewise satisfied John of Parma who desired peace, which the report of his sermon indicates. After he passed his examinations,131 and with the support of the University faculty,132 the university Chancelrae, 1924), vii-viii, identifies the correct date as 7 October 1255. The Bull is anonymously translated in Franciscan Studies 5 (1945): 350-51, which contains the correct dating. 128 CUP I, n. 219, 242-43; also see Traver, Rewriting History? 13. 129 Such an exchange had already occurred between Alexander of Hales and John of La Rochelle in 1241 when John moved to the public chair and Alexander to the private chair. On this point, see Dufeil, Guillaume de Saint-Amour, 6, and Glorieux, DAlexandre de Hals Pierre Auriol, 268-69. Moreover, it is clear that William was in Paris a year later when Alexander IV commissioned him to finish the Summa fratris; on this point see footnote 127. 130 See footnote 110 and related text. 131 Bougerol, Introduction (1988), 5, claims that Bonaventure completed his examinations for the licentia docendi before 25 November 1253. 132 Robert Curzons 1215 code of statutes defines the related roles of the chancellor and the masters (CUP I, n. 20, 80): the chancellor must confer on all candidates examined and recommended by the majority of the masters Later, Gregory IXs bull Parens scientiarum (CUP I, n. 117, 163) confirms that the faculty had to examine and vote on candidates

Dating Bonaventures inception as regent Master

213

lor granted Bonaventure the licentia docendi in January 1254.133 In that same month two other events relating to Bonaventures licensing and inception occurred. The first provides inferential evidence that Bonaventures licensing was not contested. On 29 January, Innocent IV instructed Aimeric to grant the licentia docendi to the Cistercian Guy of Aumone.134 However, Aimeric ignored the request because he likely lacked faculty support.135 The seculars would not have cooperated with Guys examination because licensing him would directly undermine Quoniam in promotione (February 1252). Thus, Aimerics inaction signals that there were problems regarding the licensing of new regulars, which implies that the faculty and Aimeric did not oppose Bonaventures licensing. Again, I am doubtful that opposition to Bonaventures inception and regency would have been passed over in silence. The second supplies explicit evidence that Bonaventure, at the time of his licensing, was formulating ideas that would later appear in his inception sermon. On 6 January,136 Bonaventure delivered an Epiphany sermon