Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Incremental VALIDITY of Locus of CONTROL

Transféré par

tomorDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Incremental VALIDITY of Locus of CONTROL

Transféré par

tomorDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 19, No. 4, Summer 2005 (2005) DOI: 10.

1007/s10869-005-4519-1

INCREMENTAL VALIDITY OF LOCUS OF CONTROL AFTER CONTROLLING FOR COGNITIVE ABILITY AND CONSCIENTIOUSNESS Keith Hattrup

San Diego State University

Matthew S. OConnell

Select International, Inc.

Jeffrey R. Labrador

Central Michigan University

ABSTRACT: This research examined the criterion-related validity of work-specic locus of control in predicting job performance, including incremental validity after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Data from a student sample and from a large employee sample were used to evaluate the scale properties of measures of locus of control, conscientiousness, and cognitive ability. Two concurrent criterion-related validation studies were then conducted to evaluate the incremental validity of locus of control. In both validation studies, locus of control demonstrated overall and incremental relationships with performance after controlling for ability and conscientiousness, such that employees with higher internal locus of control performed more effectively than externals. KEY WORDS: job performance; locus of control; personality.

INTRODUCTION Prior to the 1990s, many authors concluded that personality was not strongly related to individual job performance (e.g., Guion & Gottier, 1965; Hunter & Hunter, 1984; Schmitt, Gooding, Noe, & Kirsch, 1984).

Address correspondence to Keith Hattrup, Department of psychology, San Deigo State University, 5500 Campanile Dr. San Diego, CA, 92182-4611, USA., E-mail: keattrup@sunstroke.sdsu.edu. 461

0889-3268/05/0600-0461/0 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.

462

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

More recently, interest in the use of personality as a predictor of job performance has grown, in part because of the emergence of a comprehensive taxonomy of personality dimensions (e.g., Digman, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 1987), and meta-analytic evidence of the validity of personality dimensions in predicting job performance (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Tett, Jackson, & Rothstein, 1991). In particular, ve factors, often referred to as the Big 5 or Five Factor Model (FFM), have emerged in studies of the factor structure of personality (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 1985). These factors are: (a) Openness to Experience, (b) Conscientiousness, (c) Extraversion, (d) Agreeableness, and (e) Neuroticism. Of the ve factors, conscientiousness provides the most consistently valid prediction of performance across jobs and organizations (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000). Furthermore, conscientiousness demonstrates incremental validity in predicting job performance after controlling for cognitive ability (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). Nevertheless, a number of researchers have questioned the comprehensiveness of the FFM, identifying additional personality dimensions that appear relevant to job performance (e.g., Hough, 1992; Judge, Erez, & Bono, 1998). Others have suggested that the ve factors may be too broad, and that prediction of job performance may be improved by relying on narrower sub-dimensions of the FFM (e.g., Ashton, 1998; Hough, 1992; Schneider, Hough, & Dunnette, 1996). Of the personality traits that have been suggested to reside outside of the FFM, or that may represent an important sub-dimension of a broader job-relevant personality factor, locus of control has been identied as a potentially valid predictor of job performance (Spector, 1982). Recently, Hough (1992) reported that locus of control correlated signicantly with work outcomes, but was missing entirely from the Big Five (p. 153). A number of studies have demonstrated signicant relationships between work-specic locus of control and measures of job performance (e.g., Blau, 1993; Hough, Eaton, Dunnette, Kamp, & McCloy, 1990; Macan, Trusty, & Trimble, 1996; Spector, 1988). And, a recent meta-analysis by Judge and Bono (2001) reported a corrected correlation between job performance and locus of control that was equal to that of conscientiousness (p. 85). Clearly, locus of control appears to have potential in predicting performance at work. Although evidence supports the criterion-related validity of locus of control, largely unexplored is the incremental validity of locus of control after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Hence, the purpose of the present study is to examine the incremental validity of a measure of work-specic locus of control in predicting job performance, after controlling for general cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Thus, the present study is designed to contribute to our knowledge about

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 463

the role of a specic job-relevant trait in the prediction of job performance after controlling for general cognitive ability and a broad conscientiousness factor. Criterion-Related Validity of Conscientiousness Optimism about the usefulness of personality measures in predicting job performance criteria is largely attributed to two developments. First, it is thought that earlier pessimistic conclusions about the validity of personality were due to the lack of a common framework for organizing personality dimensions (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991). By applying the FFM developed by other researchers (e.g., Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1981; McCrae & Costa, 1987), Barrick and Mount (1991) were able to demonstrate generalizable relationships between conscientiousness and job performance criteria. Subsequent meta-analyses (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1995; Hurtz & Donovan, 2000; Salgado, 1997; Tett et al., 1991) also reported useful criterion-related validities of dimensions of the FFM, particularly conscientiousness. A second development is the recognition that personality measures that are developed on the basis of a job analysis are conceptually more job-relevant and therefore, more likely to be job related (e.g., Weiss & Adler, 1984). Thus, conscientiousness is thought to relate to job performance because of its focus on behaviors that are relevant to effectiveness in organizations. Research has also demonstrated that conscientiousness adds incrementally to the prediction of job performance above that predicted by cognitive ability (e.g., Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). This is because cognitive ability and conscientiousness correlate with somewhat different dimensions of job performance. Whereas cognitive ability correlates highest with performance of core transformation and maintenance activities, or task performance, work orientation and conscientiousness correlate more strongly with behaviors that support and maintain the organizational context, or contextual performance (e.g., Hattrup, OConnell, & Wingate, 1998; Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994; McHenry, Hough, Toquam, Hanson, & Ashworth, 1990). Criterion-Related Validity of Locus of Control Locus of control refers to a generalized expectancy that outcomes, such as the attainment of rewards or the avoidance of punishment, are controlled by ones own actions (internal locus of control) or by external factors (external locus of control) (e.g., Spector, 1982, 1988). Persons with an internal locus of control believe that reinforcements are determined by personal effort, ability, and initiative, whereas persons with an external locus of control tend to believe that reinforcements are determined by

464

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

other persons, luck, or fate (OBrien, 1984). Internal locus of control is negatively related to anxiety (Spector, 1982), which is conceptually similar to the neuroticism dimension of the FFM, and is positively correlated with achievement orientation. Research has shown that individuals with higher internal locus of control report less stress, less anxiety, higher work motivation, and are more likely to emerge as leaders than persons with higher external locus of control (Spector, 1982). Currently, there is a lack of consensus in the literature about the relationship between locus of control and the FFM. Hough (1992) for example, argued that the prediction of job performance requires more than ve broad factors, and that instead, at least nine personality factors are necessary, including locus of control. Similarly, Tett et als. (1991) meta-analysis of the criterion-related validities of personality dimensions in predicting job performance included locus of control as a trait factor that was independent of the FFM. In contrast, Costa and McCrae (1992) suggested that locus of control is a part of the broader conscientiousness factor (see also Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoreson, 2002a,b). More recently, a number of studies has provided evidence that locus of control may be a sub-dimension of a broader Core Self-Evaluations construct, along with self-esteem, self-efcacy, and neuroticism (Bono & Judge, 2003; Erez & Judge, 2001; Judge & Bono, 2001; Judge et al., 2002a,b). According to these authors, core self-evaluations may represent a broad factor neuroticism factor (Bono & Judge, 2003; Erez & Judge, 2001; Judge & Bono, 2001; Judge et al., 2002a,b). Thus, it appears that locus of control has been considered as an independent factor and as a sub-dimension of conscientiousness, neuroticism, or core self-evaluations. Despite some lack of consensus about the relationship of locus of control to the FFM, it is clear that most authors consider locus of control to represent a specic, rather than broad, personality trait. Evidence of relationships between locus of control and job performance has appeared in the literature (OBrien, 1984; Spector, 1982). Hough (1992), for example, reported an average observed correlation of .19 across 11 studies between locus of control and overall job performance, such that internals performed better than externals. Only measures of achievement orientation correlated as highly with overall performance in this study as locus of control. Tett et al. (1991) reported a weaker relationship in their meta-analysis (q = .13) between higher internal locus of control and better job performance, although their results were based on a smaller number of studies (k = 7). A more comprehensive recent meta-analysis by Judge and Bono (2001) reported a corrected validity of .22 (k = 35). Studies of the processes underlying relationships between locus of control and performance suggest that internals perceive higher expectancies that effort will lead to good performance, and that performance

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 465

will lead to valued outcomes, than do externals (e.g., Lied & Pritchard, 1976; Mitchell, Smyser, & Weed, 1975; Szilagyi & Sims, 1975). Hence, internals demonstrate higher task motivation, as long as valued job rewards are perceived to be linked to performance levels (Spector, 1982). Further, internals are more likely than externals to react to stress with behavioral responses rather than emotional reactions (e.g., Anderson, Hellreigel, & Slocum, 1977). Internals also demonstrate more workgroup cooperation, self-reliance, and independence than do externals (e.g., Cravens & Worchel, 1977; Tseng, 1970). Because of its correlation with achievement orientation, motivation, and conscientiousness, it is reasonable to expect positive correlations between internal locus of control and measures of general cognitive ability. Thus, substantial empirical evidence demonstrates that locus of control has direct relationships with job performance. Locus of control also appears to provide incremental prediction after controlling for cognitive ability (Blau, 1993). These ndings underscore a need to further explore the nomological network of work-specic locus of control and its unique relationships with job performance. Of particular interest is the extent to which locus of control adds incrementally to the prediction of job performance after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Given research demonstrating low to moderate correlations between locus of control and conscientiousness (e.g., Morrison, 1997), and signicant relationships between locus of control and job performance (e.g., Blau, 1993), we predict that locus of control will correlate positively with job performance and will add incrementally to the prediction of performance after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. We predict that internals will perform their jobs more effectively than externals, and that this relationship will hold after controlling for the effects of cognitive ability and conscientiousness. As noted above, research has demonstrated that conscientiousness and work orientation relate more strongly to contextual behaviors at work than to behaviors reecting task performance (e.g., Hough et al., 1990; Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994). Hough et al., (1990) also reported stronger relationships between several other personality measures, including locus of control, and measures of effort and leadership, personal discipline, and physical tness and military bearing, than between the same personality scales and measures of technical prociency and general soldiering prociency. These results lead to the expectation that locus of control will relate more strongly to contextual performance than to task performance. The Measurement of Locus of Control A variety of measures of locus of control has appeared in the literature (e.g., Lefcourt, 1976, 1981; Rotter, 1966). Several authors have

466

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

argued that measures that focus on locus of control in a specic domain should correlate more strongly with behavior in the same domain than would general measures (e.g., Lefcourt, 1976, 1981; Stipek & Weisz, 1981). For example, Blau (1993) reported stronger relationships between a work-specic locus of control measure (Spector, 1988) and several job performance criteria, compared to Rotters general measure. Thus, goalspecic measures of locus of control have been developed for a variety of specic purposes or populations (e.g., Crandall, Katkovsky, & Crandall, 1965; Donovan & OLeary, 1978; Montag & Comrey, 1987; Wallston & Wallston, 1981; Wong, Watters, & Sproule, 1978). Given the focus of the present study on the prediction of job performance, a measure of locus of control for outcomes of work-related behaviors is of most relevance. Hence, the present research examines a measure of work-specic locus of control, and measures of conscientiousness and cognitive ability, that were developed as part of a computerized multi-attribute test battery designed for use in the selection of entry- and mid-level production workers.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE WORK-SPECIFIC LOCUS OF CONTROL SCALE Several steps were followed in developing the work-specic locus of control measure. A review of the literature led to the development of an initial pool of 35 items, which were subsequently administered to a sample of 85 applicants for retail sales positions. Responses were provided on a 5-point scale, anchored strongly disagree to strongly agree. Internal consistency reliability analyses were used to identify 16 items, which were then administered to a sample of 54 retail store managers and 40 undergraduate students. After scoring all items so that higher levels of agreement indicated internal locus of control, and lower levels of agreement indicated higher external locus of control, item-total correlations were examined, and a single item was chosen for elimination from the measure. The 15-item scale was then administered to an additional group of 49 applicants for retail sales positions, along with Rotters (1966) locus of control scale. The correlation between the two scales was .50, which is very similar to the correlation observed between the work-specic locus of control measure described by Spector (1988) and Rotters (1966) scale (Blau, 1993; Spector, 1988). As described below, the resulting 15-item scale was then examined using two normative samples, including a sample of college undergraduates and a large sample of job applicants and incumbents in various positions in organizations throughout the United States. Its criterionrelated validity and incremental validity were examined in two local concurrent validation studies.

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 467

NORMATIVE STUDIES Method Samples and Procedures Data were collected from two samples to evaluate the internal consistency and intercorrelations involving the locus of control scale, the proprietary measures of conscientiousness and cognitive ability that were used in the subsequent validation studies, and a published measure of each of the dimensions of the FFM. The rst sample included 77 undergraduate students at a large public university in the Midwestern U.S. Participants in the student sample completed paper-and-pencil versions of the locus of control scale described above, the conscientiousness measure described below, and the International Personality Item Pool indicators of the FFM (Goldberg, 1999; International Personality Item Pool, 2001). The second normative sample included 3491 applicants and incumbents from eight manufacturing rms operating in the Midwestern U.S. The positions encompassed a wide range of entry to mid-level manufacturing, assembly, and operator positions, and included repetitive light, moderate, and heavy manufacturing jobs, as well as more sophisticated operator positions focusing on monitoring and troubleshooting processes. Participants completed the 15-item locus of control measure, along with the proprietary measures of conscientiousness and cognitive ability described below, using a computer. Applicants were administered the measures during pre-employment testing, whereas incumbent participants were randomly selected from the organizations current pool of employees to complete the measures during work hours in a proctored administration. Measures Work-Specic Locus of Control. The 15-item measure described above was administered in both normative samples. The student sample was too small to perform exploratory factor analysis, so this sample was used only to evaluate the intercorrelations between the measures used in this research and a published measure of the FFM. In this student sample, the 15-item locus of control scale had an internal consistency reliability of .56. The same 15-items were administered to the larger employee sample. In this sample, exploratory principal factors analysis with varimax rotation identied anywhere from one to three distinct factors, cumulatively accounting for 19.6, 31.3, and 39.3% of the item variance, respectively. Items were retained for factors if their loadings exceeded .30 on a factor and were at least .10 larger than their loadings on alternative factors. Both the two and three factor solutions separated the subset of

468

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

positively worded items from the subset of reverse-worded items, and the Alpha reliabilities of scales formed from these solutions ranged from .52 to .71. Because neither factor solution was consistent with existing theoretical models of the dimensionality of locus of control, and because there was little empirical support for retaining scales formed from the two and three factor solutions, we evaluated the scale properties of the composite formed from all 15 items. This analysis identied a single item that showed a low item-total correlation (r = .03), and that when deleted, resulted in a 14-item work-specic locus of control measure with an internal consistency reliability of .65. Scale scores were formed after recoding items so that higher levels of agreement indicated higher internal locus of control. The 14-item measure was then used in all subsequent analyses involving the employee sample used in the normative phase of the research, and the two validation studies described below. Conscientiousness. A 23-item work-specic conscientiousness scale described by Hattrup et al., (1998) was included in the battery of tests administered to participants in this research. This measure was designed to reect the broad conscientiousness factor, and hence, included four items reecting hard work/achievement/work ethic, three items related to persistence, six items related to effective use of time (versus wasting time), three items related to detail orientation, four items related to impulse control, two items related to physical appearance/presentation, and one item that reected decisiveness (see Hough & Ones, 2001, for a comparison of facets). Hattrup et al., (1998) reported an internal consistency of .70, and correlations of .23 and .24 between the measure and measures of organizational citizenship and absenteeism, respectively. Items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale anchored Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Internal consistency reliability in the student sample was .72 and was .73 in the employee sample. Cognitive Ability. A 26-item cognitive ability measure was developed to reect three broad domains, including analytical reasoning, numerical reasoning, and applied reasoning. These domains were considered relevant to the jobs of interest given the requirements of each job for problem solving, manipulation of quantitative information, and reliable performance of assembly and production tasks. Items were scored dichotomously, and the sum across the 26 items was used as the composite ability score. The ability measure was administered in the employee normative sample. Internal consistency reliability of 26-item ability measure was .81 in this sample. Five Factor Model. The 50-item IPIP measure of the FFM (Goldberg, 1999; International Personality Item Pool, 2001) was administered to the student sample. The IPIP is a publicly available pool of items that is

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 469

designed, in part, to measure the ve broad factors of the FFM. Participants use a 5-point Likert response scale to indicate the extent to which each item is, as a self-description, very inaccurate to very accurate. The IPIP (International Personality Item Pool, 2001) reports internal consistencies of each of the 10-item factor scales that range between .79 and .87. In the present student sample, internal consistencies ranged between .74 and .91. Results and Discussion Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the measures administered to the student sample. As can be seen, the 23-item conscientiousness measure used in this research demonstrated good convergent validity with the IPIP conscientiousness scale, as indicated by the large correlation between these variables. As expected, the 23-item conscientiousness scale had much lower correlations with the other four dimensions of the FFM. The locus of control scale correlated .15 with the 23-item conscientiousness scale, and .07 with the IPIP conscientiousness scale. Its correlations with the other dimensions of the FFM were also small. Thus, the locus of control scale appears relatively independent of the FFM, suggesting that it may either reside outside the FFM as suggested by Hough (1992), or may represent a specic sub-component of a very broad conscientiousness factor as suggested by Costa and McCrae (1992), or a broad self-evaluations factor (Judge & Bono, 2001). Whatever the conceptual relationships between locus of control and the FFM and core self-evaluations, the results of the present study suggest that the criterion-related validity of locus of control in predicting job performance is not accounted for by the broader dimensions of the FFM.

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency Reliabilities, and Intercorrelations of Variables in the Student Sample (N = 77) Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 23-Item conscientiousness 15-Item locus of control IPIP conscientiousness IPIP extraversion IPIP neuroticism IPIP agreeableness IPIP openness *p < .05. Mean 3.38 3.18 3.58 3.38 3.24 4.27 3.66 SD .36 .31 .58 .36 .81 .50 .53 1 (.72) .15 .74* .27* .26* .20 .21 2 3 4 5 6 7

(.56) .07 .04 .14 .15 .18

(.84) .41* .25* .19 .20

(.89) .05 .13 .24*

(.91) .05 .19

(.87) .10

(.74)

470

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the measures that were administered to the larger employee normative sample. As can be seen, locus of control correlated signicantly with the 23-item conscientiousness measure, suggesting that persons who are higher in conscientiousness are more likely to be high in internal locus of control than persons who are lower in conscientiousness. Internal locus of control also correlated positively with the measure of cognitive ability (r = .08), as did conscientiousness (r = .11). Thus, the data collected in two samples showed a good pattern of convergent and discriminant validity of the locus of control and conscientiousness measures used in this research with measures of the FFM and cognitive ability. Of more direct relevance to the goals of the present study, however, is whether locus of control incrementally predicts job performance after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. These relationships are examined in the validation studies reported below.

VALIDATION STUDY 1 Method Sample and Procedure Participants in this study included 121 operators at a paint processing facility in the U.S., including 106 male employees, 13 female employees, and two others for whom gender information was unavailable. Participants were randomly selected from current employees who had been working in the company for at least 1 year. They completed the cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and locus of control measures described above as part of a larger research project, during work hours in a proctored administration. All three measures were administered and scored by computer. Job performance of the sample was evaluated by immediate supervisors. Participants in this study monitored machines and equipment used in the processing of paints and dyes that are used for coloring various products. Hence, the job required paying attention to

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency Reliabilities, and Intercorrelations of Variables Examined in the Normative Sample (N = 3491) Variable 1. Cognitive ability 2. Conscientiousness 3. Locus of control **p < .01. Mean 13.51 3.92 3.69 SD 4.79 .31 .39 1 (.81) .11** .08** 2 3 4

(.73) .51**

(.65)

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 471

detail, monitoring production processes, and developing unique solutions to novel problems. Measures The cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and locus of control measures described above were administered. Internal consistency reliabilities were .78, .72, and .65, respectively, in the present sample. Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and internal consistency reliabilities of these measures in the present sample. Job Performance. Supervisors rated the job performance of participants using a 10-item graphic rating measure. Each of the 10 items represented a dimension of job performance that had been identied in a job analysis, including initiative, work motivation, leadership, dependability, attention to detail, practical learning, teamwork, technical knowledge, and quantitative and qualitative problem solving. Supervisors used a 10-point rating scale to indicate how effectively the ratee had demonstrated behaviors related to each dimension. An exploratory principal factors analysis with varimax rotation was performed in the sample of 121 participants in the validation sample. Items were assigned to a factor if their loadings on the factor exceeded .30 and were at least .10 different from their loadings on alternative factors. The qualitative problem solving item was eliminated from the analysis because it correlated 1.0 with the quantitative problem solving item. A three factor solution, accounting for about 77% of the variance in the items, appeared most interpretable. The rst factor was comprised of the items measuring leadership, teamwork, and positive attitude, and thus, is consistent with the interpersonal facilitation dimension of contextual performance described by Van Scotter and Motowidlo (1996). The second factor included the conscientiousness, initiative, work motivation, and practial learning items, and thus, is consistent with the job dedication dimension of performance described by Van Scotter and Motowidlo (1996). The third factor included the technical knowledge and quantitative problem solving items, and was most consistent with the dimension of task performance, described by several authors (Borman & Motowidlo, 1993; Motowidlo et al., 1997). Internal consistency reliabilities of the interpersonal facilitation, job dedication, and task performance scales were .85, .81, and .77, respectively. As can be seen in Table 3, intercorrelations among the three job performance scales ranged from .53 to .69. Results and Discussion Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the predictor and criterion variables examined in this study.

472

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

Table 3 Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency Reliabilities, and Intercorrelations of Variables Examined in Validation Study 1 (N = 121) Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Cognitive Ability Conscientiousness Locus of control Task performance Job dedication Interpersonal facilitation *p < .05, **p < .01. Mean 14.40 3.47 3.23 6.03 5.93 5.61 SD 5.09 .29 .36 1.49 1.37 1.41 1 (.78) .09 .18* .23* .27** .25** 2 3 4 5 6

(.72) .57** .02 .18* .14

(.65) .19* .31** .38**

(.77) .69** .53**

(.81) .62**

(.85)

As can be seen, conscientiousness showed a strong relationship with locus of control (r = .57). Cognitive ability correlated signicantly with locus of control but not with conscientiousness. As can be seen in Table 3, cognitive ability was signicantly related to all three performance dimensions, which is somewhat inconsistent with previous research demonstrating stronger correlations between cognitive ability and task performance than between cognitive ability and dimensions of contextual performance (e.g., McHenry et al., 1990; see also Motowidlo et al., 1997). Conscientiousness correlated signicantly only with the job dedication dimension (r = .18), which is consistent with the suggestion of Van Scotter and Motowidlo that job dediction should be predictable from scores on measures of conscientiousness, whereas interpersonal facilitation should be predicted from agreeableness and extraversion. The results are also consistent with previous research demonstrating stronger relationships between conscientiousness or work orientation and contextual performance than between these predictors and task performance (e.g., McHenry et al., 1990; see also Motowidlo et al., 1997; Murphy & Shiarella, 1997). Follow-up tests of differences in dependent correlations (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) showed that conscientiousness was more strongly correlated with the job dedication scale than with the task performance scale, whereas no other differences in the criterion-related validity coefcients for conscientiousness were signicant. Locus of control correlated signicantly with all three performance dimensions, demonstrating more effective task performance, job dedication, and interpersonal facilitation among employees who were higher in internal locus of control. Follow-up tests revealed that locus of control was more strongly correlated with the interpersonal facilitation dimension than with the task performance dimension, although no other differences in correlations involving locus of control and the criteria were signicant. The strong correlation between internal locus of control and interpersonal facilitation is consistent with previous research demonstrating positive relationships between internal locus of control and

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 473

effectiveness in leadership and teamwork roles (e.g., Anderson & Schneier, 1978; Goodstadt & Hjelle, 1973). Table 4 presents results of regressions designed to evaluate the incremental validity of locus of control in predicting the three job performance dimensions. As can be seen, conscientiousness failed to show unique relationships with any of the job performance dimensions when used in conjunction with cognitive ability. This result is inconsistent with ndings that suggest generalizability of the relationship between conscientiousness and job performance across settings (e.g., Barrick & Mount, 1991), and incremental validity of conscientiousness above the effects of cognitive ability (e.g., Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). On the other hand, the results of this study may be consistent with ndings from other research which shows that conscientiousness is often unrelated or negatively related to performance of tasks that require creativity, initiative, and problem solving (e.g., George & Zhou, 2001; Hogan & Hogan, 1995). Effective performance in the job examined in this study required that employees identify unique solutions to novel problems. Rule-bound or rigid adherence to standardized problem solutions would result in incomplete or slower solutions than approaches that involve innovative solutions. As would be expected in such jobs, cognitive ability was signicantly related to ratings of effectiveness, and conscientiousness correlated signicantly only with job dedication. It is important to note, however, that creativity is often considered an aspect of openness, rather than low conscientiousness (see Hough & Ones, 2001). Table 4 shows that locus of control added incrementally to the prediction of all three performance dimensions after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. The positive sign of the regression coefcient for locus of control indicates that participants who scored higher in

Table 4 Regressions of Task Performance, Job Dedication, and Interpersonal Facilitation on Cognitive Ability and Personality Measures in Validation Study 1 (N = 121) Task Performance Independent Variables Step 1 Cognitive ability Conscientiousness Step 2 Cognitive ability Conscientiousness Locus of control *p < .05, **p < .01. b R

2

Job Dedication b R

2

Interpersonal Facil

2

DR

DR

R2 .08**

DR2

.05* .23 .00

*

.10** .25 .16

**

.24 .12 .14** .04*

**

.08* .20* .12 .22*

.03* .22* .01 .26*

.19** .19* .11 .41**

.11**

474

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

internal locus of control demonstrated better task performance, job dedication, and interpersonal facilitation than participants with higher external locus of control, even after controlling for the effects of cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Thus, the results of Study 1 underscore the job-relevance of locus of control as a potentially important predictor of job performance. A second validation study was conducted to assess the generalizability of these effects in a job that was characterized by different demands and performance expectations. VALIDATION STUDY 2 Method Sample and Procedure Participants in this study included 113 male and 29 female production workers at a large automobile manufacturing facility in the U.S. As in the rst validation study, participants were randomly selected from current employees who had been working in the company for at least one year. They completed the assessment as part of a larger research project during work hours in a proctored administration, and were assured that the results would be used only for research purposes. Their job performance was rated by their direct supervisors. Employees worked as Production Team Members, and were trained in a variety of the functions involved in the manufacture of automobiles, including paint, body, nal assembly, trim, and so on. According to a job analysis, effectiveness depended on attention to detail, work pace, and periodic cooperation with coworkers to resolve unexpected problems. Measures Predictors. The measures of cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and locus of control were administered by computer, as described above. Internal consistency reliabilities of the ability, conscientiousness, and locus of control measures were .47, .74, and .58, respectively, in Validation Study 2. The lower reliabilities of the ability and locus of control measures in the second validation study, as compared to the normative sample and rst validation study, are difcult to interpret, but may be partly a result of the lower variances of these two measures in the second validation sample as compared to the other samples. Job Performance. Supervisors rated incumbents performance using a 32-item behavioral observation measure. Items described examples of effective or ineffective behavior in each of seven job areas, including organizational citizenship, work pace, teamwork, quality awareness, problem solving, responsibility, and exibility. Between three and 10

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 475

items were written for each dimension. Supervisors rated the frequency with which each of the 32 behaviors was observed using a 7-point Likert scale, with anchors Never to Always. Exploratory principal factors analysis with varimax rotation failed to converge on an interpretable solution, owing to the large number of very highly correlated items in the measure. We also formed a contextual performance scale by averaging scores on the organizational citizenship, teamwork, responsibility, and exibility subscales; and a task performance scale by averaging scores on the quality awareness, problem solving, and work pace. The correlation between the task and contextual performance scales was .89, and predictors showed almost identical relationships with the two performance dimensions. Thus, results strongly suggest that a composite unidimensional performance measure best ts the pattern of responses in Validation Study 2. The internal consistency reliability (Alpha) of the performance measure in this sample was .97. Results and Discussion Table 5 presents the correlations among locus of control, conscientiousness, cognitive ability, and job performance. As can be seen, conscientiousness and locus of control were signicantly correlated, as was the case in the normative sample and in Study 1. In the present sample, about 21% of the variance was shared between the locus of control measure and the conscientiousness scale, which is similar to the results observed in the normative sample and rst validation sample. As can be seen in Table 5, both conscientiousness and locus of control were signicantly related to the job performance measure. The positive correlation between conscientiousness and performance is consistent with literature that demonstrates positive effects of conscientiousness on performance of tasks that do not require high levels of creativity and innovativeness. The non-signicant correlation between cognitive ability

Table 5 Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency Reliabilities, and Intercorrelations of Variables Examined in Validation Study 2 (N = 142) Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. Cognitive ability Conscientiousness Locus of control Job performance ratings *p < .05, **p < .01. Mean 15.18 3.57 3.44 4.72 SD 2.85 .31 .30 .86 1 (.47) .04 .10 .03 2 3 4

(.74) .46** .28**

(.58) .27**

(.97)

476

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

Table 6 Regressions of Job Performance on Cognitive Ability and Personality Measures in Validation Study 2 (N = 142) Variables Step 1. Cognitive ability Conscientiousness Step 2. Cognitive ability Conscientiousness Locus of control *p < .05, **p < .01. b R2 .08** .02 .28** .11** .01 .20* .18* .03* DR2

and performance may be the result of lower internal consistency of the ability measure in this sample. Table 6 presents the results of regression analyses designed to test the incremental validity of locus of control. As can be seen, conscientiousness had unique effects on performance after controlling for ability. Locus of control also added incrementally to the prediction of performance after controlling for ability and conscientiousness. These ndings are consistent with the results of Study 1, which showed a similar incremental relationship between locus of control and job performance after controlling for both ability and conscientiousness. (Table 4)

GENERAL DISCUSSION The goal of this research was to examine the incremental validity of locus of control in predicting job performance, after controlling for the effects of cognitive ability and conscientiousness. As hypothesized, locus of control showed signicant incremental relationships with job performance after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. The ndings of the present study are consistent with research that has demonstrated signicant validity associated with locus of control when predicting job performance (e.g., Blau, 1993; Hough, 1992; Judge & Bono, 2001). The unique contribution of the present study is in demonstrating incremental relationships between locus of control and job performance, after controlling for both cognitive ability and a measure of conscientiousness. The incremental effects of locus of control on ratings of job performance demonstrate that unique variance in the criterion is accounted for

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 477

by locus of control. From a practical point of view, locus of control explained an additional .03 to .11 proportion of variance in job performance after accounting for ability and conscientiousness. Schmidt and Hunter (1998) reported that conscientiousness added .09 to the proportion of criterion variance explained by cognitive ability, whereas job knowledge measures, assessment centers, and biodata added only .07, .02, and .01, respectively. Results of the present study demonstrate that, after controlling for two constructs commonly used in the selection of personnel, locus of control adds an increment to the proportion of explained job performance variance that compares favorably to the increment added by job knowledge tests, assessment centers, biodata, education, or job experience above cognitive ability alone. Clearly, the results underscore a need for additional research that evaluates relationships between locus of control and the FFM and core self-evaluations, and that tests various theoretical models that include locus of control as a specic trait relevant to work-related behaviors. From a theoretical point of view, the incremental validity of locus of control suggests a need to better ascertain the substantive meaning of the criterion variance that is uniquely explained by locus of control. Studies that have addressed the incremental effects of conscientiousness on job performance have demonstrated that one important reason for the unique effects of conscientiousness is that ability and conscientiousness relate to somewhat different dimensions of job performance (e.g., Motowidlo et al., 1997; Motowidlo & VanScotter, 1994). Results of Study 1 were somewhat consistent with this previous research in that conscientiousness correlated signicantly only with the measure of job dedication, and its correlation with job dedication was signicantly greater than its correlation with task performance. In the same sample, locus of control was more strongly correlated with the interpersonal facilitation dimension of performance than with task performance, suggesting that locus of control may contribute to performance by increasing the likelihood that workers will form positive relationships with others, demonstrate leadership, and exhibit positive attitudes. It is noteworthy that locus of control was the only predictor that related uniquely to job performance criteria in both validation studies. As noted above, ability, but not conscientiousness was related to performance for employees who performed the process monitoring and troubleshooting tasks in Study 1, whereas conscientiousness, but not ability, was related to performance of assembly and teamwork behaviors in Study 2. For the most part, employees in Study 1 monitored automated chemical processing equipment, and were required to troubleshoot equipment failures and develop novel solutions to production problems. Hence, the job required abstract reasoning and problem solving, which is consistent with the recognition that process monitoring and maintenance

478

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

of automated systems is cognitively challenging (e.g., Argote, Goodman, & Schkade, 1983; Hesketh & Neal, 1999; Weick, 1990), and with our nding of a positive correlation between ability and performance in these jobs. Cognitive ability was not signicantly related to performance in the jobs examined in Study 2, however. The jobs examined in Study 2 involved simple production and assembly tasks, and hence, previous research leads to the expectation of a relatively lower correlation between ability and performance than was observed in Study 1, due to the relative lack of signicant cognitive demands (e.g., Hunter & Hunter, 1984). The ndings of the present research with respect to conscientiousness also provided mixed support for previous research. On one hand, conscientiousness related signicantly and incrementally with performance in Study 2. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating incremental relationships between conscientiousness and overall job performance (e.g., Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). In Study 1, however, conscientiousness correlated signicantly with job dedication, but not with task performance or interpersonal facilitation. Hence, results of the present study are consistent with Van Scotter and Motowidlos (1996) suggestion that conscientiousness should relate mainly to job dedication, whereas interpersonal facilitation and task performance are predictable from other constructs. Of course, the studies reported here are not without limitations. Perhaps most signicant is the use of unpublished measures of key constructs in the present study, which is often considered less desirable than using measures with more well-known psychometric properties. However, results demonstrated acceptable levels of internal consistency of each of the measures used in this research, although the internal consistency of the locus of control scale was somewhat lower. Results of the two normative studies and two validation studies were generally consistent with our hypotheses, and with the extant literature. Moreover, the measure of conscientiousness used in this research was shown in a previous study to relate signicantly with measures of organizational citizenship and attendance (Hattrup et al., 1998). The available empirical literature includes a variety of validation studies that use disparate measures of ability and personality constructs, and the use of proprietary measures in eld research is not uncommon. Overall, the evidence obtained in the present research provides strong support for the incremental effects of locus of control on job performance after controlling for cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Researchers should attempt to replicate these ndings in eld settings using a variety of instruments. Carefully designed research that varies measurement methods and constructs will contribute substantially to our understanding of the latent individual difference constructs underlying performance in organizations. It is also hoped that the

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 479

present ndings might contribute to future meta-analytic research designed to identify relationships among various ability and personality constructs and various job performance dimensions. Such research has the potential to provide more power to detect stable relationships at the population level. Although the samples used in both validation studies reported here were moderate in size, some non-signicant results may have been observed due to low statistical power. Researchers are urged to follow-up on the present ndings with additional large sample eld research and meta-analytic investigations. The results of this research clearly demonstrate the need for researchers to look beyond conscientiousness and the FFM, and to consider other specic personality variables that may have considerable usefulness in predicting valued outcomes in organizations. Locus of control appears to offer this potential.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C. R., Hellriegel, D. & Slocum, J. W. (1977). Managerial response to environmentally induced stress. Academy of Management Journal, 201, 260272. Anderson, C. R. & Schneier, C. E. (1978). Locus of control, leader behavior, and leader performance among management students. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 690698. Argote, L., Goodman, P. S. & Schkade, D. (1983). The human side of robotics: How workers react to a robot. Sloan Management Review, 24, 3141. Ashton, M. C. (1998). Personality and job performance: The importance of narrow traits. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 289303. Barrick, M. R. & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big 5 personality dimensions and job performance. Personnel Psychology, 44, 125. Blau, G. (1993). Testing the relationship of locus of control to different performance dimensions. Journal of Organizational and Occupational Psychology, 66, 125138. Costa, P. T. Jr. & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways ve factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 653665. Crandall, V. C., Kratovsky, W. & Crandall, V. J. (1965). Childrens beliefs in their control of reinforcements in intellectual achievement behaviors. Child Development, 36, 91109. Cravens, R. W. & Worchel, P. (1977). The differential effects of rewarding and coercive leaders on group members differing in locus of control. Journal of Personality, 45, 150168. Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the ve factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417440. Donovan, D. M. & OLeary, M. R. (1978). The drinking-related locus of control scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 39, 759784. Erez, A. & Judge, T. A. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations to goal setting, motivation, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 12701279. George, J. M. & Zhou, J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 513524. Goldberg, L. R. (1981). Language and individual differences: The search for universals in personality lexicons. Review of personality and social psychology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage 141166. Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several ve-factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. De

480

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND PSYCHOLOGY

Fruyt & F. Ostendorf (Eds.). Personality psychology in Europe (pp. 728). Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press. Goodstadt, B. E. & Hjelle, L. A. (1973). Power to the powerless: Locus of control and the use of power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27, 190196. Guion, R. M. & Gottier, R. F. (1965). Validity of personality measures in personnel selection. Personnel Psychology, 18, 135164. Hattrup, K., OConnell, M. S. & Wingate, P. H. (1998). Prediction of multidimensional criteria: Distinguishing task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 11, 305319. Hesketh, A. & Neal, A. (1999). Technology and performance. In D. R. Ilgen & E. D. Pulakos (Eds.). The changing nature of performance, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hogan, R. & Hogan, J. (1995). Hogan personality inventory manual. 2nd, Tulsa, OK: Hogan Assessment Systems. Hough, L. M. (1992). The ,Big Five personality variablesconstruct confusion: description versus prediction. Human Performance, 5, 139155. Hough, L. M., Eaton, N. L., Dunnette, M. D., Kamp, J. D. & McCloy, R. A. (1990). Criterionrelated validities of personality constructs and the effect of response distortion on those validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 581595. Hough, L. M. & Ones, D. S. (2001). The structure, measurement, validity, and use of personality variables in industrial, work, and organizational psychology. In N. Anderson, D. S. Ones, H. K. Sinangil, & C Viswesvaran (Eds.). Handbook of industrial, work, and organizational psychology (pp. 233277). London: Sage. Hunter, J. E. & Hunter, R. F. (1984). Validity and utility of alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 7298. Hurtz, G. M. & Donovan, J. J. (2000). Personality and job performance: The Big 5 revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 869879. International Personality Item Pool (2001). A Scientic Collaboratory for the Development of Advanced Measures of Personality Traits and Other Individual Differences (http://ipip.ori.org/). Internet Web Site. Judge, T. A. & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluation traits self-esteem, generalized self-efcacy, locus of control, and emotional stability with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 8092. Judge, T. A., Erez, A. & Bono, J. E. (1998). The power of being positive: The relation between positive self-concept and job performance. Human Performance, 11, 167187. Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E. & Thoreson, C. J. (2002a). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control and generalized self-efcacy indicators of a common construct?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 693710. Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E. & Thoreson, C. J. (2002b). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56, 303331. Lefcourt, H. M. (1976). Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research. New York: Wiley. Lefcourt, H. M. (1981). Research with the locus of control construct: Volume 1, Assessment methods. New York: Academic Press. Lied, T. R. & Pritchard, R. D. (1976). Relationships between personality variables and components of the expectancy-valence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 463467. Macan, T. H., Trusty, M. L. & Trimble, S. K. (1996). Spectors work locus of control scale: Dimensionality and validity evidence. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56, 349357. McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr. (1985). Updating Normans adequate taxonomy: Intelligence and personality dimensions in natural language and in questionnaires. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 710721. McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr. (1987). Validation of the ve-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 8190. McHenry, J. J., Hough, L. M., Toquam, J. L., Hanson, M. A. & Ashworth, S. (1990). Project a validity results: the relationship between predictor and criterion domains. Personnel Psychology, 43, 335354.

KEITH HATTRUP, MATTHEW S. OCONNELL, AND JEFFREY R. LABRADOR 481

Mitchell, T. R., Smyser, C. M. & Weed, S. E. (1975). Locus of control: Supervision and work satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 18, 623631. Montag, I. & Comrey, A. L. (1987). Internality and externality as correlates of involvement in fatal driving accidents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 339343. Morrison, K. A. (1997). Personality correlates of the ve-factor model for a sample of business owners/managers: Associations with scores on self-monitoring, Type A behavior, locus of control, and subjective well-being. Psychological Reports, 80, 255272. Motowidlo, S. J., Borman, W. C. & Schmit, M. J. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 10, 7183. Motowidlo, S. J. & Van Scotter, J. R. (1994). Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 475480. Murphy, K. R. & Shiarella, A. H. (1997). Implications of the multidimensional nature of job performance for the validity of selection tests: Multivariate frameworks for studying test validity. Personnel Psychology, 50, 823854. OBrien, G. E. (1984). Locus of control, work, and retirement. In H. M. Lefcourt (Eds.). Research with the locus of control construct (Vol. 3): Extensions and limitations, New York: Academic Press. Rotter, J. B. (1996). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, (Whole No. 609). Salgado, J. F. (1997). The ve factor model of personality and job performance in the European community. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 3043. Schmidt, F. L. & Hunter, J. E. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research ndings. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 262274. Schmitt, N., Gooding, R. Z., Noe, R. A. & Kirsch, M. (1984). Meta-analysis of validity studies published between 1964 and 1984 and the investigation of study characteristics. Personnel Psychology, 37, 407422. Schneider, R. J., Hough, L. M. & Dunnette, M. D. (1996). Broadsided by broad traits: How to sink science in ve dimensions or less. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 639655. Spector, P. E. (1982). Behavior in organizations as a function of employees locus of control. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 482497. Spector, P. E. (1988). Development of the work locus of control scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61, 335340. Stipek, D. J. & Weisz, J. R. (1981). Perceived personal control and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 51, 101137. Szilagyi, A. D. & Sims, H. P. (1975). Locus of control and expectancies across multiple occupational levels. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 638640. Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N. & Rothstein, M. (1991). Personality measures as predictors of job performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44, 703742. Tseng, M. S. (1970). Locus of control as a determinant of job prociency, employability, and training satisfaction of vocational rehabilitation clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 17, 487491. Van Scotter, J. R. & Motowidlo, S. J. (1996). Interpersonal facilitation and job dedication as separate facets of contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 525531. Wallston, K. A. & Wallston, B. S. (1981). Health locus of control scales. In H. M. Lefcourt (Eds.). Research with the locus of control construct (pp. 189244). New York: Academic Press. Weick, K. E. (1990). Technology as equivoque: Sensemaking in new technologies. In P. S. Goodman, L. S. Sproull & Associates (Eds.). Technology and organizations (pp. 144). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Weiss, H. M. & Adler, S. (1984). Personality and organizational behavior. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.). Research in organizational behavior (pp. 150). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Wong, P. T. P., Watters, D. A. & Sproule, C. F. (1978). Initial validity and reliability of the Trent Attribution Prole as a measure of attribution schema and locus of control. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38, 11291134.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Amex Leadership ApproachDocument31 pagesAmex Leadership ApproachtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- MCK Will Ai Make You A Better Leader 04 2018Document3 pagesMCK Will Ai Make You A Better Leader 04 2018tomorPas encore d'évaluation

- LEADERSHIP Theory and PracticeDocument4 pagesLEADERSHIP Theory and Practicetomor20% (5)

- Strategic BULLYING As A Supplementary Balanced Perspective On Destructive LEADERSHIPDocument12 pagesStrategic BULLYING As A Supplementary Balanced Perspective On Destructive LEADERSHIPtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparing Outcome Measures Derived From Four Research DesignsDocument89 pagesComparing Outcome Measures Derived From Four Research DesignstomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Workforce Training CatalogDocument12 pagesWorkforce Training CatalogtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Selection Optimization and Compensation To Reduce Job Family STRESSORSDocument29 pagesUsing Selection Optimization and Compensation To Reduce Job Family STRESSORStomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Development of A Private Sector Version of The TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP QUESTIONNDocument18 pagesDevelopment of A Private Sector Version of The TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP QUESTIONNtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- International Workshop On NeuroinformaticsDocument27 pagesInternational Workshop On NeuroinformaticstomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Collaborative PMDocument19 pagesCollaborative PMtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive PERFORMANCE Assessment in English LOCAL GovernmentDocument14 pagesComprehensive PERFORMANCE Assessment in English LOCAL GovernmenttomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Investigating Different Sources of ORG CHANGEDocument16 pagesInvestigating Different Sources of ORG CHANGEtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee OWNERSHIP and AccountabilityDocument5 pagesEmployee OWNERSHIP and Accountabilitytomor100% (1)

- Articulating Appraisal SystemDocument25 pagesArticulating Appraisal SystemtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Managerial Experience SND The MEASUREMENTDocument15 pagesManagerial Experience SND The MEASUREMENTtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effects of Job Relevance Commission and HRM EXPERIENCE PDFDocument9 pagesThe Effects of Job Relevance Commission and HRM EXPERIENCE PDFtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Uncertainty During ORG CHANGEDocument26 pagesUncertainty During ORG CHANGEtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Measurement Equivalence and Multisource RatingsDocument27 pagesMeasurement Equivalence and Multisource RatingstomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Personality and Intelligence in Business PeopleDocument11 pagesPersonality and Intelligence in Business Peopletomor100% (1)

- Perspectives On Nonconventional Job Analysis MethodologiesDocument12 pagesPerspectives On Nonconventional Job Analysis MethodologiestomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Leader ResponsivenessDocument15 pagesLeader ResponsivenesstomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Is Personality Related To Assessment Center Performance? - Journal of Business PsychologyDocument13 pagesIs Personality Related To Assessment Center Performance? - Journal of Business PsychologyDavid W. AndersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing Employees in The SERVICE SECTORDocument23 pagesManaging Employees in The SERVICE SECTORtomor100% (1)

- The Dvelopment and Validation of A PERSONOLOGICAL Measure of Work DRIVEDocument25 pagesThe Dvelopment and Validation of A PERSONOLOGICAL Measure of Work DRIVEtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Internationalizing 360 Degree FedbackDocument22 pagesInternationalizing 360 Degree FedbacktomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Influences of Traits and Assessment Methods On HRMDocument16 pagesInfluences of Traits and Assessment Methods On HRMtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Image Theory and The APPRAISALDocument20 pagesImage Theory and The APPRAISALtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Do People Fake On Personality InventoriesDocument21 pagesDo People Fake On Personality InventoriestomorPas encore d'évaluation

- Hierarchical Approach For Selecting PERSONALITYDocument15 pagesHierarchical Approach For Selecting PERSONALITYtomorPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Factors Affecting The Implementation of Green Procurement: Empirical Evidence From Indonesian Educational InstitutionDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting The Implementation of Green Procurement: Empirical Evidence From Indonesian Educational InstitutionYeni Saro ManaluPas encore d'évaluation

- Intel Server RoadmapDocument19 pagesIntel Server Roadmapjinish.K.GPas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument18 pagesPDFDental LabPas encore d'évaluation

- CPI As A KPIDocument13 pagesCPI As A KPIKS LimPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case Study From The: PhilippinesDocument2 pagesA Case Study From The: PhilippinesNimPas encore d'évaluation

- Midterm Quiz 01 - Adjusting Entries From Accrual To Provision For Uncollectible AccountsDocument3 pagesMidterm Quiz 01 - Adjusting Entries From Accrual To Provision For Uncollectible AccountsGarp Barroca100% (1)

- Hardening'-Australian For Transformation: A Monograph by MAJ David J. Wainwright Australian Regular ArmyDocument89 pagesHardening'-Australian For Transformation: A Monograph by MAJ David J. Wainwright Australian Regular ArmyJet VissanuPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 1 PDFDocument18 pages2 1 PDFالمهندسوليدالطويلPas encore d'évaluation

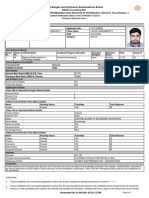

- West Bengal Joint Entrance Examinations Board: Provisional Admission LetterDocument2 pagesWest Bengal Joint Entrance Examinations Board: Provisional Admission Lettertapas chakrabortyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ex 6 Duo - 2021 Open-Macroeconomics Basic Concepts: Part 1: Multple ChoicesDocument6 pagesEx 6 Duo - 2021 Open-Macroeconomics Basic Concepts: Part 1: Multple ChoicesTuyền Lý Thị LamPas encore d'évaluation

- Lec05-Brute Force PDFDocument55 pagesLec05-Brute Force PDFHu D APas encore d'évaluation

- ReleaseNoteRSViewME 5 10 02Document12 pagesReleaseNoteRSViewME 5 10 02Jose Luis Chavez LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comprehensive Review On Renewable and Sustainable Heating Systems For Poultry FarmingDocument22 pagesA Comprehensive Review On Renewable and Sustainable Heating Systems For Poultry FarmingPl TorrPas encore d'évaluation

- Instructions: This Affidavit Should Be Executed by The PersonDocument1 pageInstructions: This Affidavit Should Be Executed by The PersonspcbankingPas encore d'évaluation

- Current Matching Control System For Multi-Terminal DC Transmission To Integrate Offshore Wind FarmsDocument6 pagesCurrent Matching Control System For Multi-Terminal DC Transmission To Integrate Offshore Wind FarmsJackie ChuPas encore d'évaluation

- Q3 Week 1 Homeroom Guidance JGRDocument9 pagesQ3 Week 1 Homeroom Guidance JGRJasmin Goot Rayos50% (4)

- Basic Details: Government Eprocurement SystemDocument4 pagesBasic Details: Government Eprocurement SystemNhai VijayawadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tankguard AR: Technical Data SheetDocument5 pagesTankguard AR: Technical Data SheetAzar SKPas encore d'évaluation

- Negative Sequence Current in Wind Turbines Type 3 1637954804Document6 pagesNegative Sequence Current in Wind Turbines Type 3 1637954804Chandra R. SirendenPas encore d'évaluation

- Claim Age Pension FormDocument25 pagesClaim Age Pension FormMark LordPas encore d'évaluation

- Mobile Fire Extinguishers. Characteristics, Performance and Test MethodsDocument28 pagesMobile Fire Extinguishers. Characteristics, Performance and Test MethodsSawita LertsupochavanichPas encore d'évaluation

- Phet Body Group 1 ScienceDocument42 pagesPhet Body Group 1 ScienceMebel Alicante GenodepanonPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Handmade Carpets EnglishDocument16 pagesIndian Handmade Carpets EnglishVasim AnsariPas encore d'évaluation

- Wheel CylindersDocument2 pagesWheel Cylindersparahu ariefPas encore d'évaluation

- 3UF70121AU000 Datasheet enDocument7 pages3UF70121AU000 Datasheet enJuan Perez PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- 1. Cẩm Nang Sửa Chữa Hệ Thống Điện Xe Honda Civic 2012Document138 pages1. Cẩm Nang Sửa Chữa Hệ Thống Điện Xe Honda Civic 2012Ngọc NamPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Answers Chap 002Document174 pagesFinal Answers Chap 002valderramadavid67% (6)

- Audit Process - Performing Substantive TestDocument49 pagesAudit Process - Performing Substantive TestBooks and Stuffs100% (1)

- As 3789.2-1991 Textiles For Health Care Facilities and Institutions Theatre Linen and Pre-PacksDocument9 pagesAs 3789.2-1991 Textiles For Health Care Facilities and Institutions Theatre Linen and Pre-PacksSAI Global - APACPas encore d'évaluation

- Scout Activities On The Indian Railways - Original Order: MC No. SubjectDocument4 pagesScout Activities On The Indian Railways - Original Order: MC No. SubjectVikasvijay SinghPas encore d'évaluation