Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Michael W. Clune On Masters of The Universe

Transféré par

Dave GreenTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Michael W. Clune On Masters of The Universe

Transféré par

Dave GreenDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

February 26th, 2013 Michael W. Clune on Masters of the Universe What Was Neoliberalism?

Masters of the Universe : Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics by: Daniel Stedman Jones date: 08.27.2012 pp: 424 HOW DID IT HAPPEN? In the early 1970s, Western governments, academia, and the me dia understood the relationship between the state and the market according to th e same liberal consensus that had been in place since the end of World War II. D uring what is commonly called the golden age of capitalism, government, capital, a nd labor had reached the uneasy agreement that markets produced social ruin when left to their own devices. The state was needed to mitigate inequality, to prov ide basic services, and through a combination of monetary and fiscal means to ev en out capitalism s boom-bust cycle. By the early 1980s, all that had changed: the British and American governments, joined by large segments of the media and int elligentsia, declared that the state was the root of social evil, that free mark ets could do nearly everything better than government, and that the economic cri ses of the past were the result of state meddling. This view is often called neoliberalism, a term first used by interwar continental and British economists and philosophers to describe an economic doctrine that f avors privatization, deregulation, and unfettered free markets over public insti tutions and government. These philosophers saw themselves as championing the val ues of classical liberalism in a mid-20th century world threatened by unchecked state power a threat vividly embodied in the totalitarian societies of Nazi Germ any and Stalinist Russia. Writers like Ludwig von Mises and Karl Popper saw hope in the liberalism of J.S. Mill and Adam Smith. They shared the earlier philosop hers skepticism about the capacity of human reason to design functional and ethic al social orders, and were committed to processes of liberated or open exchange to create knowledge and distribute wealth. The meaning of the prefix has aroused a great deal of debate. For thinkers on th e left, neo signals a liberalism shorn of many of the features that made classical liberalism plausible and effective. Recent scholarship on Adam Smith, for examp le, has emphasized the extent to which neoliberal thinkers such as F. A. Hayek f ocus on Smith s celebration of self-organizing markets in The Wealth of Nations wh ile neglecting Smith s argument, in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, for the import ance of non-market values in sustaining social orders. Indeed, the neoliberal em brace of the prospect of a social world almost wholly organized by market relati ons strongly distinguishes this thought from the classical liberal tradition, wh ich fostered a capitalism embedded in the institutions of civil society, the nor ms of civilized communication, and state regulation of the economy. There are two popular accounts of how this philosophy of free markets and minima l government came to determine the economic policies of the US and UK. For the r ight, including the heirs and acolytes of Milton Friedman, the failures of both state socialism and the Keynesian welfare state made the political triumph of ne oliberal ideas inevitable. For the left, including figures like the Marxist geog rapher David Harvey and the activist-journalist Naomi Klein, neoliberal policies were the expression of the interests of capital, which systematically infiltrat ed government in order to reverse postwar regulations. In Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politic

s, the economic historian Daniel Stedman Jones persuasively argues that both the se popular accounts are wrong. That neoliberalism won out was due neither to the failures of the welfare state nor to a master plan pushed by the agents of capita l. The story Stedman Jones tells is considerably more nuanced. He shows neoliber alism s ascendance to be the result of a series of more or less ad hoc moves on th e part of politicians, activists, media figures, and economists in response to a series of political and economic shocks that began in the 1970s. The image of a dramatic face-off between neoliberals and proponents of the postwar center-left consensus is largely an artifact of retrospective right-wing propaganda, which the left seems to have accepted in its essential features. The main lines of Stedman Jones s narrative are as follows: The appearance of stag flation in the 1970s, and the perceived inability of conventional economic wisdo m to account for or mitigate it, made left governments in the US and UK receptiv e to certain technical policy adjustments, collectively known as monetarism, to co mbat inflation. Monetarists believe that control over the money supply should be the chief means that governments use to moderate the fluctuations of a national economy, as opposed to the view (derived from John Maynard Keynes) that both mo netary and fiscal intervention could (and should) be used to tame the business c ycle. The intellectual sponsors of these monetarist policies, Milton Friedman an d his acolytes at the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, an d the University of Chicago economics department, also tended to believe in the power of free markets to organize society more efficiently than the state. But i f both Jimmy Carter s Democratic and James Callaghan s Labor administrations accepte d the monetarist policies, and began to implement them, they rejected the free m arket philosophy. The application of these monetarist policies tamed inflation, but not before dee pening the recession and contributing to the ouster of the Democrats and Labour. The conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan that succee ded them claimed that neoliberal free market thinking had rescued America and Br itain, and that these ideas should be systematically implemented to solve a rang e of economic and social questions going forward. This narrative, that neolibera lism emerged victorious from Keynesianism s inability to deal with stagflation, wo n widespread acceptance. Pushing against this dominant account, Stedman Jones disassembles the monolithic neoliberalism of left and right myth into several conceptually and historically separate elements, which he shows came together in a lucky way at a particular mo ment in history. These elements are: A) A network of intellectuals joined by belief in the power of free markets, ini tially centered on F. A. Hayek s Mont Pelerin Society, later exerted force through conservative and libertarian think tanks and economics departments in Chicago a nd Virginia. B) Milton Friedman s development of monetarism into a viable economic policy rival to the reigning Keynesian approach. C) The economic crises of the 1970s, ranging from the collapse of the Bretton Wo ods agreement, to the OPEC oil shocks, culminating in runaway inflation and high unemployment. Stedman Jones quotes Friedman s statement that the role of thinkers [ ] is primarily to keep options open, to have available alternatives, so when the brute force of events make a change inevitable, there is an alternative available. When the wor st postwar economic crisis discredited Keynesian orthodoxy, Friedman was ready w ith an attractive technical solution. In turn, a transatlantic network of intell ectuals and journalists figures like Ed Fuelner of the Heritage Foundation, Samu el Brittan of the Financial Times, and Peter Jay of the BBC was ready to cast th

e distinction between these policies, not only in technical terms, but also as a n epochal choice between the welfare state and the free market. Rather than emerging from any sort of master plan, it was, in fact, a series of lo cal choices in the face of unyielding inflation, the Carter administration s appoi ntment of Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board in 1979, or the reluctant decision of Hayekian free marketeers to make uneasy peace with social conservatives that led to the neoliberal breakthrough. Stedman Jones traces the rise of neoliberalism to the decision of left-leaning g overnments to adopt monetarist policies. His description of this decision is per haps the most distinctive aspect of his account. To understand how his argument challenges what we think we know of neoliberalism, we need to take a step back, and take a closer look. Discussions of neoliberalism, on both the left and the right, suffer from what P aul Krugman and others have called zombie ideas. These are economic concepts that have been long discredited, but continue to shamble on. On the right, a central zombie idea is that reduced state regulation of markets leads to sustainable eco nomic growth. If you believe this, then the rise of neoliberalism is a no-braine r. Neoliberalism is simply the economic philosophy that works. But why should an yone believe this? The idea that unleashing free markets then leads to good econ omic times should never have survived the Great Depression, and should surely be killed for good by the Great Recession and its aftermath. Meanwhile, a new generation of leftist economists has discovered that their prog ressive brethren suffer from a zombie idea of their own. Mike Beggs, for example , has recently argued that the Marxist economics many on the left continue to fi nd attractive has a fatal flaw. Marx believed in the labor theory of value, the idea that a commodity s value is equal to the labor that goes into it. Generations of Marxist thinkers have built on this foundation to form a picture of the way the world s economy works. Thinkers like David Harvey have used this theory to cre ate a sophisticated explanation of neoliberalism as the natural response of capi tal to changing conditions. If you subscribe to Harvey s Marxist theory, then the rise of neoliberalism is, again, a no-brainer. But as Beggs points out, the conc ept underlying theories like Harvey s was decisively disproved over a century ago, and no one has ever come up with a persuasive defense. Once we see that the no-brainer explanations of neoliberalism are in fact zombie s, then the question becomes truly interesting. How did the governments of the W estern world come to embrace this radical free market philosophy? Stedman Jones answer is: they didn t. What they did accept was monetarism. Monetarism the idea t hat one can smooth out economic cycles by controlling the money supply was inven ted by Milton Friedman, a neoliberal. And virtually everyone on both the left an d the right associates monetarism with the neoliberal commitment to free markets . But, as Stedman Jones argues, these are two very different things, and history turns on this difference. Monetarism is a government policy for manipulating the economy. The free market is the vision of an economy liberated from government control. Understanding how a rather technical policy approach came to be identified with the love of free markets opens an entirely new approach to the fundamental economic and political transformation of our time. And understanding how this identification came to b e resisted allows us to understand the longevity of the biggest zombie of all: t he tendency to blame government for everything that s wrong with the economy. The story of monetarism begins with the way in which Keynesian orthodoxy came to dominate economic policy in the English-speaking democracies. The basic logic o f this orthodoxy is familiar. The Great Depression spectacularly illuminated cap italism s tendency to periodically implode, but the problem was not just that the

cyclical busts seemed to be getting worse and that the resulting unemployment th reatened social stability. Keynes argued that even the eventual recoveries could not be relied on to productively employ the population. He saw a basic gap betw een social goals and the outcomes produced by markets. Government, however, coul d overcome this gap. Through loose monetary policy and spending by the state, we could counter the cyclical waning of demand, restoring full employment. Then, w hen the economy threatened to overheat, we could raise taxes and tighten the mon ey supply to control inflation. Vast wartime spending reversed America s unemployment problem and fueled the prest ige of the Keynesian approach. A Keynesian technocratic elite rose to control the levers of fiscal and monetary policy, hoping to ensure the country would never a gain suffer a devastating depression. This Keynesian faith in the power of gover nment to solve social problems meshed with broader liberal goals to invest in th e nation s infrastructure, to create a health care safety net, to defeat poverty t hat were pursued by successive Democratic and Republican administrations. And wh ile virulent racists and anticommunists increasingly protested these social prog rams, when it came to economic policy, as Nixon famously said, everyone was a Ke ynesian. But the economic technocrats had an Achilles heel. Stedman Jones points out that although Keynes doubted that managing supply and demand could ever become an exa ct science, his heirs came to believe that advances in statistics gave them acce ss to fine-grained, timely economic data, which they could use to strike the swe et spot of low unemployment and low inflation. However, events were soon to prov e their confidence hubristic. Milton Friedman, meanwhile, had been developing an alternative mode of governmen t control over markets, one with much more modest goals, and animated by skepticis m about the ability of any centralized administration to gather accurate and upto-date information about a complex modern economy. He dismissed the Keynesian t echnocrats idea that one could achieve low inflation and full employment, arguing that the application of inevitably crude fiscal tools to lift employment would always tend to increase inflation. It was far better, he thought, to restrict ce ntral economic policy to what it could do well: control inflation by controlling the supply of money. The coming of stagflation, and the seeming incapacity of economic orthodoxy to d eal with it, discredited the Keynesians and lifted the monetarists. Economic pol icy didn t seem to be working, and as the 1970s progressed, the pressure to make a change became irresistible. Monetarists ascended to key policy positions, but t his ascent did not mark the capitulation of center-left governing practices to t he neoliberal faith in free markets, as right-wingers like to claim. The idea th at accepting monetarism meant accepting free markets is the result of a retrospe ctive conflation of monetarism with a theoretically separate set of arguments abo ut the supposed superiority of markets over government intervention in the econo my. At first glance, this seems a strange claim, given both Friedman s status as a pri me exponent of free-market thinking, and the fact that compared with Keynesianis m monetarism represents a relatively restricted mode of government economic inte rvention. Isn t opting for monetarism simply a form of opting for greater freedom for markets? But in fact, as Stedman Jones argues, monetarism is not the same as the neoliber al faith in markets. Monetarism is not nor did it appear to policy makers in the 1970s to be a laissez-faire program. Rather, it is a program for government con trol of economic volatility. Given stagflation, the choice between monetarism an d Keynesianism looked less like an ideological choice and more like a choice bet ween two techniques of state intervention.

The fact that people, at the time, could clearly perceive a distinction between monetarist policy and neoliberal philosophy is illustrated in Hayek s extreme reac tion to Friedman s plan. Hayek advocated the abolition of legal tender, and the sp ontaneous, market-driven creation of private currencies. From the other directio n, Democratic and Labour governments with little interest in freeing markets fro m government could adopt monetarist policy solutions without believing they were admitting the bankruptcy of the welfare state. The latter interpretation was st rictly rear-view, Stedman Jones claims. And had events like the Iran hostage cri sis not intervened, he argues, the story of liberal capitulation and failure mig ht never have served to justify the implementation of genuinely neoliberal polic ies in the 1980s and 1990s. Stedman Jones s careful history offers us a genuinely new account of the rise of n eoliberalism by demonstrating that the link between monetarism and free markets was not obvious it was forged in the fires of conservative ideology. But a flaw in his historical analysis prevents him from drawing the full implications of th is fact. This flaw becomes visible in his conclusion, when he dismisses the desi re for the free market as a delusion and calls for a return to sanity in economic policy. His plea finds many echoes in today s center-left observers of our politic al scene. But while Stedman Jones judges the enthusiasm for free markets as esse ntially inexplicable, a boundless faith in free market logic keeps welling up in the story he tells, thus undercutting his effort to present the rise of neolibe ralism as the result of rational decisions. One can, of course, easily sympathize with his assessment of the desire for a fr ee market. This enthusiasm doesn t seem to have an obvious source. Every historica l event from the advent of the Great Depression under laissez-faire policies, to the advent of the Golden Age of Capitalism under Keynesian statism, to the fina ncial panic of 2008 under deregulation seems to undercut it. Still, he acknowled ges that the conservative success in framing the economic story of the late 1970 s and early 1980s as the triumph of markets over states, for example, drew upon a broad and deep existing enthusiasm for free markets in the population. Stedman Jones never accounts for why. Even more troubling, the love of free markets won t stay in the right political bo x. In his chapter on neoliberal housing policy, for example, he initially contra sts the conservative, proto-neoliberal emphasis on single-family suburban home o wnership with the leftist urban vision of Jane Jacobs. But he soon suggests that the idea of curing urban ills with free market enterprise zones was inspired by t he pro-commerce, anti-planning vision of Jane Jacobs. One comes away from Masters of the Universe with the unsettling impression that many of the players in his story on both sides of the political spectrum are somehow predisposed to enthusi asm about the prospect of free markets. This doesn t exactly undercut his narrativ e of neoliberalism s political triumph, but it does alter our sense of the social and cultural context of this triumph in ways the book only fleetingly acknowledg es. Stedman Jones shows us the gap between the monetarist manipulation of the econom y and the commitment to free markets. One might argue that this gap is more wide ly intuited today than Stedman Jones recognizes. Moreover, skepticism about the proposition that monetarism is a free market solution to economic crisis applies t o other neoliberal policies that are said to promote free exchange. Many on the left, and the right, saw that what was being marketed as free market policy by R eagan and Thatcher was, in fact, an insidious form of government manipulation. M uch of the political resistance of the past three decades has focused on distanc e between a social world, organized by genuinely free exchange, and the forms of government control identified with free markets by successive neoliberal admini strations. The sense of this distance enables people on both the far right and t he far left to claim, with justice, that the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions wer

e founded on lies, that neoliberalism s ascent witnessed not the retreat of govern ment, but its insidious extension. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri s attempt to cl aim the slogan down with big government for the left, and the end the fed signs that appeared at both Occupy and Tea Party rallies, are symptoms of a pervasive beli ef that free exchange has yet to triumph over the state. Clearly, a work of political history like Stedman Jones s does not nor should it retend to delineate the shape of popular free market utopias, to analyze why the idea of free markets is so widely appealing, or to trace the routes of its cult ural dissemination. Yet he leaves us with too many unanswered questions to justi fy his concluding dismissal of it as insanity. We may very well conclude not that free market ideology has coopted the left, bu t that resistance to actually existing capitalism now takes a form inassimilable to the political positions of the early postwar period. Perhaps Jane Jacobs is different from Milton Friedman after all. Perhaps there are two visions of the f ree market, left and right, and we will one day look back on the postwar period as the emergence of a new form of ideological struggle. For now, the scale of th e problem is visible only in the distortions it causes in so sober a history as this one. Recommended Reads Response to "What Was Neoliberalism?": A Debate Between Joshua Clover / Jasper Be rnes and Michael W. Clune by Jasper Bernes, Joshua Clover and Michael W. Clune Privatizing Paradise in the Murder Capital of the World by James McGirk Privatized Prisons: A Human Marketplace by Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones Jon Wiener on How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism by Eric Ho bsbawm "The Age of Revolution" The Great Shock by Brian Collins No More Bubblegum by Mike Davis Shaun Randol interviews Jason Kelly "Private Equity Planet: Jason Kelly on 'The N ew Tycoons'" G.J. Meyer on Thinking the Twentieth Century by Tony Judt and Timothy Snyder "Val ediction" Plutocratic Vistas by George Scialabba Timothy Spangler on Double Entry by Jane Gleeson-White "Every Accountant Tells a Story" Timothy Spangler on Pound Foolish by Helaine Olen "Easy Come, Easy Go: The Dark S ide of Personal Finance" Timothy Spangler on Wealth and Poverty and Free Market Revolution by George Gilde r, Yaron Brook and Don Watkins "The New New Capitalism Comments: Kyle T. Your characterization of Mike Beggs' ideas about the Labour Theory of Value is n ot really honest. You write: "Mike Beggs, for example, has recently argued that the Marxist economics many on the left continue to find attractive has a fatal flaw. Marx believed in the lab or theory of value, the idea that a commodity s value is equal to the labor that g oes into it...But as Beggs points out, the concept underlying theories like Harv ey s was decisively disproved over a century ago, and no one has ever come up with a persuasive defense." Taking a look at Beggs' article, he writes: "I have suggested that there are elements in Capital that point beyond the labor theory of value and towards supply-and-demand analysis,and I believe that any a dequate theory of value needs to do this. It is not such a challenge to the basi p

c results of the labor-value analysis as it may seem, either. Alfred Marshall hi mself argued in an appendix to his Principles of Economics that his marginalist analysis did not undermine Ricardo s theory of long-run value...There is little fo r Marxists to fear from importing the concepts of supply and demand schedules. T he critical importance of labor time does not disappear, but can actually be put on a firmer footing, because it makes possible (1) a more elegant treatment of relative prices than the classical multi-stage analysis in which the impact of l abor, capital and land are dealt with sequentially; and (2) a framework for deal ing with relative prices in both the short and long run, and the relationship be tween them, whereas the classical analysis generally neglects or leaves the shor t run indeterminate." There is a yawning gap between these two statements. Beggs' position seems to be that Marx's methods in Capital are not so much WRONG as they are unwieldy and p oorly suited to examining short-term price fluctuations. Whereas you write that Harvey's arguments are utterly without basis, Beggs argues that in the long-term Marx's LTV is a reasonable basis for analysis. Given that Harvey's analysis is in fact of a long-term development, it is actually your dismissal of his argumen ts that is unfounded. Kyle T. Your assertion that: "We may very well conclude not that free market ideology has coopted the left, b ut that resistance to actually existing capitalism now takes a form inassimilabl e to the political positions of the early postwar period. Perhaps Jane Jacobs is different from Milton Friedman after all.Perhaps there are two visions of the f ree market, left and right, and we will one day look back on the postwar period as the emergence of a new form of ideological struggle. For now, the scale of th e problem is visible only in the distortions it causes in so sober a history as this one." Is also problematic. It is certainly true that high modernist technocracy was re jected by both the left and the right from the 1970s onwards, but "resistance to actually existing capitalism" has (in the critique of neoliberalism and the dem and for regulation) often referred back to the paternalist "political positions of the early postwar period." This is certainly not a consistent position (deman ding liberty and regulation at once) but it is a position that is actually artic ulated in these confused times. Now if we talk about market socialism, which is about as close to a "left vision of the free market" as one could get (outside o f middle-class localist fantasies that abstract their neighbourhoods' Jacobs-sty le markets from all the social and economic conditions that support them) we fin d that aggressive state intervention would absolutely be required to maintain th e idyllic scenario of small producers and merchants carrying on their business ( Given that the natural tendency of actually existing markets is in fact to produ ce monopolies). This is not to say that the market socialist utopian vision is i mpossible to realize, but its existence would have little to do with the suppose dly "self-correcting" and "free" market. Michael W. Clune Please see my response to Clover and Bernes, on this site, for a detailed reply to the claim that I distort Beggs' ideas. Beggs does charitably point out that t he intellectual context of the early 80's gave a certain support to the scholast icism of writers like Harvey. But that moment has passed. If it is in fact the c ase that Beggs believes that Harvey's ignorance of the basics of economic histor y has no effect on the latter's predictions, I must respectfully disagree! But I don't see how this follows from the main thrust of his argument. Robert Hamilton A major source of free marketeers' ascendance was the success of deregulation an d privatisation in transportation and telecommunications. The push toward deregu

lation started under Jimmy Carter in the United States, a few years before Marga ret Thatcher was even elected, with the effective deregulation of the airline in dustry, quickly followed by railways and trucking. A driving force was senator T ed kennedy, not exactly a creature of the right. Deregulation of telecomminications in the U.S.was driven by the courts. In most other countries it started when governments privatised the service provider. The point is, these reforms worked. Prices fell, sometimes dramatically, and, ex cept for the airlines, service improved. Except for a few on the progressive out er fringe, nobody speaks of reversing these reforms. The mistake was to see the free market doctrine work in a few markets and conclu de that it would work in all markets. But hasty generalizations are common in po licy circles. They should not be over-interpreted, as either conspiracies or tri umphs of ideology. jansand It is interesting that there is no acknowledgement of the influence that powerfu l and highly financially endowed corporations have had on the decisions of gover nment and how they have corrupted almost entirely any motivations for the genera l benefit of the populace to be replaced by government responsive to the benefit of the corporate interests. Since politicians are interested in remaining in po wer and corporate funding has seen to it that they may do so the political scene has become completely controlled by those wealthy enough to see to it who remai ns in power. Jon Jermey It's arguable that the Great Depression was triggered by the lag between shares being sold and the price information subsequently reaching those people who woul d have bought them on the way down and arrested their drop. In other words, the share market didn't reach the information requirements for it to be accurately d escribed as 'free'. Al_de_Baran No, it's not "arguable". The stock market crash was only one feature of the Grea t Depression as a whole, and not even the most important one. Also, if "free mar kets" are judged by the technical information-sharing capabilities of the future , then by definition no past market is ever "free". rigaud Free Markets-what a good idea. Why don't we try it. ramesh rghuvanshi Real meaning of neoliberalism is neocolonialism ,after second world war when all colonies of western countries were dislocated they want new way to sale manufac turing goods to poor countries.Luckily ultramodern communication system just lik e Internet, mobile and other fast devices helped them to spread their business w orld over very cheap way.Free market helped rich countries tremendously they are earning more than in colonial era. They higher cyber coolies , hardware coolies very cheap prices.China India ,Philippines are greatest hub of collies and west ern countries are enjoying the huge profit without responsibility of armed threa t.

http://lareviewofbooks.org/article.php?type=&id=1445&fulltext=1&media=

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Globalist's Plan To Depopulate The PlanetDocument16 pagesGlobalist's Plan To Depopulate The PlanetEverman's Cafe100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Dana Property Law OutlineDocument32 pagesDana Property Law Outlinedboybaggin50% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Slavery - The West IndiesDocument66 pagesSlavery - The West IndiesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (2)

- Jurisprudence Notes - Nature and Scope of JurisprudenceDocument11 pagesJurisprudence Notes - Nature and Scope of JurisprudenceMoniruzzaman Juror100% (4)

- Philippine Declaration of IndependenceDocument2 pagesPhilippine Declaration of Independenceelyse yumul100% (1)

- Diplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Document42 pagesDiplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Jeremiah Miko Lepasana100% (1)

- 2nd School Faculty Conference Minutes of MeetingDocument4 pages2nd School Faculty Conference Minutes of MeetingKrizzie Joy CailingPas encore d'évaluation

- Barbri Notes Personal JurisdictionDocument28 pagesBarbri Notes Personal Jurisdictionaconklin20100% (1)

- Pocso ActDocument73 pagesPocso ActRashmi RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- TenancyDocument2 pagesTenancyIbrahim Dibal0% (2)

- Skills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitDocument4 pagesSkills Training on Catering Services cum Provision of Starter KitKim Boyles Fuentes100% (1)

- The Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Document3 pagesThe Problem With Psychiatry, The DSM,'Dave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Abortion BattlegroundDocument4 pagesThe New Abortion BattlegroundDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- On TransienceDocument2 pagesOn TransienceDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Traditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDocument9 pagesTraditional Chinese Medicine Is An OddDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDocument4 pages2013 Quotas and Longline ClosureDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Why This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDocument3 pagesWhy This Gigantic Intelligence ApparatusDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Journey Through The Checkout RacksDocument4 pagesJourney Through The Checkout RacksDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Me, Me, Me' WeddingDocument4 pagesThe Me, Me, Me' WeddingDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Egypt's High Value On VirginityDocument3 pagesEgypt's High Value On VirginityDave Green100% (1)

- The Dead Are More VisibleDocument2 pagesThe Dead Are More VisibleDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Against Environmental PanicDocument14 pagesAgainst Environmental PanicDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Portrait of The Artist As A CavemanDocument8 pagesPortrait of The Artist As A CavemanDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Hieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDocument34 pagesHieber - Language Endangerment & NationalismDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Double Helix Meets God ParticleDocument1 pageDouble Helix Meets God ParticleDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Language and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDocument7 pagesLanguage and The Socialist-Calculation ProblemDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Language As ActionDocument3 pagesLanguage As ActionDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Dis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Document202 pagesDis-Enclosure (The Deconstruction of Christianity)Dave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- France's Cul-De-SacDocument3 pagesFrance's Cul-De-SacDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lost BoysDocument3 pagesThe Lost BoysDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- How A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDocument2 pagesHow A Doctor Came To Believe in Medical MarijuanaDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Big Data Is Not Our MasterDocument2 pagesBig Data Is Not Our MasterDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Red Menace or Paper TigerDocument6 pagesRed Menace or Paper TigerDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- A Dark Night IndeedDocument12 pagesA Dark Night IndeedDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Is 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Document8 pagesIs 'Austerity' Responsible For The Crisis in Europe?Dave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDocument5 pagesThe Constitutional Amnesia of The NSA Snooping ScandalDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Numbers Don't LieDocument4 pagesThe Numbers Don't LieDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lost BoysDocument3 pagesThe Lost BoysDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- To Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDocument3 pagesTo Understand Risk, Use Your ImaginationDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- The High Cost of FreeDocument7 pagesThe High Cost of FreeDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Sympathy DeformedDocument5 pagesSympathy DeformedDave GreenPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Test Subject: Sociolinguistics Lecturer: Dr. H. Pauzan, M. Hum. M. PDDocument25 pagesFinal Test Subject: Sociolinguistics Lecturer: Dr. H. Pauzan, M. Hum. M. PDAyudia InaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Tehran Times, 16.11.2023Document8 pagesTehran Times, 16.11.2023nika242Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. B. R. Ambedkar's Role in Revival of BuddhismDocument7 pagesDr. B. R. Ambedkar's Role in Revival of BuddhismAbhilash SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Aerial Incident of 27 July 1995Document5 pagesAerial Incident of 27 July 1995Penn Angelo RomboPas encore d'évaluation

- KKDAT Form 1Document2 pagesKKDAT Form 1brivashalimar12Pas encore d'évaluation

- Saballa Sophia Conceptmap TLWRDocument2 pagesSaballa Sophia Conceptmap TLWRSophia Claire SaballaPas encore d'évaluation

- International and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and GirlsDocument32 pagesInternational and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and Girlschanlwin2007Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Characteristics of Development Paradigms: Modernization, Dependency, and MultiplicityDocument10 pagesThe Characteristics of Development Paradigms: Modernization, Dependency, and MultiplicityAmeyu Etana Kalo100% (1)

- 11-23-15 EditionDocument28 pages11-23-15 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- U.S. v. Arizona - Lawsuit Re Arizona Immigration Law (SB 1070)Document25 pagesU.S. v. Arizona - Lawsuit Re Arizona Immigration Law (SB 1070)skuhagenPas encore d'évaluation

- Ari The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong JianhuaDocument16 pagesAri The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong Jianhuaapi-232523826Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Melting Pot. Immigration in The USA.Document7 pagesThe Melting Pot. Immigration in The USA.Valeria VacaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and DesignDocument106 pagesGender-Inclusive Urban Planning and DesignEylül ErgünPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindutva As A Variant of Right Wing ExtremismDocument24 pagesHindutva As A Variant of Right Wing ExtremismSamaju GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Residents Free Days Balboa ParkDocument1 pageResidents Free Days Balboa ParkmarcelaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Rise and Goals of the Katipunan Secret SocietyDocument13 pagesThe Rise and Goals of the Katipunan Secret SocietyIsabel FlonascaPas encore d'évaluation

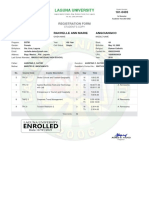

- Laguna University: Registration FormDocument1 pageLaguna University: Registration FormMonica EspinosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Latino MediaDocument358 pagesContemporary Latino MediaDavid González TolosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court rules on legality of Iloilo City ordinances regulating exit of food suppliesDocument3 pagesSupreme Court rules on legality of Iloilo City ordinances regulating exit of food suppliesIñigo Mathay Rojas100% (1)