Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Theory Course, 2011 - 10

Transféré par

Nick ShepherdDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Theory Course, 2011 - 10

Transféré par

Nick ShepherdDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

1 / 85

MUSIC THEORY

tools for creativity & understanding

HOWARD HARRISON 2010

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

2 / 85

If it sounds right, it is right.

Music Theory isnt a set of rules about how things should be - it just observes how music seems to work, and what it seems to be made of. It notices what other musicians do and have done, because we have much to learn from them - after all, it was other musicians that invented the thing in the rst place.

This document is a work in progress, something that started small and that I keep patching and extending as people seem to need it - there will subsequently be a version that includes self-testing exercises, some subjects will be covered in greater depth & it will broaden in scope. In the meantime it tells you much of what you ought to know about scales, modes, intervals and harmony in western music, and much else. I hope it is helpful.

Each stage provides information that will allow you to understand the next, so take it in order unless you are using it for reference purposes. Words in red are key terms or concepts.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

3 / 85

MUSIC THEORY

HOWARD HARRISON 2010

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

4 / 85

CONTENTS

Page numbers might be approximate! 7 SOUND

9 10

THE CHROMATIC SET First Intervals - octave, tone, semitone

11 12 13 13 14 17 18 20 21 22 24 25 27 28 29

SCALES The Major Scale Tetrachords Key Signatures The 12 major Keys Minor Scales - Natural Minor Melodic & Harmonic Minor Scales Relative Major & Minor keys Minor Key Signatures Scale Step Names Key relationships Other Scales - Modes Pentatonic Scales Whole Tone & Octatonic Scales Atonal Music

30

31

32

33

INTERVALS Harmonic & Melodic Intervals Integer Notation Pitch Class Intervals Intervals in tonal music Number & Quality Major & Perfect Intervals Minor Intervals Diminished Intervals Augmented Intervals

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

5 / 85 34 35 36 38 39 40 41 42 43 45 47 48 Consonance & Dissonance Inversions Interval Characters Intervals & Musical Style HARMONY Functional Harmony Diatonic Chords - naming them Primary Chords - The 3-chord trick Secondary Chords Hierarchy of Chords The Dominant Seventh Modal Chord Sets The Classical Minor System Rock & Pop Chord Sequences Other Chords

And more! - CHORD PROGRESSIONS . . . . . .

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

6 / 85

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

7 / 85

SOUND

Hit a drum-skin \ force air between your vocal folds \ pass uctuating electrical signals through a loudspeaker system \ squeeze a reed and blow \ twang a string - whenever you activate a musical instrument you make an elastic material wobble; you make it vibrate. When something vibrates it disturbs the air around it and the ripples that result spread through the air and ultimately disturb your ear-drum. Electrical impulses report the movements of your ear-drum to your brain and at that point the vibrations become sound. Sound is only in your head; if there's no-one there to hear it, a falling tree really does make no sound. If the ripples move your ear-drum at absolutely regular intervals, and if there are more than 20 and less than about 20,000 of them each second, the brain will perceive a steady note. The faster the vibration, the higher the note. We now hear a note with a mysterious quality; although it's obviously higher than the 440 A and therefore different, it is also strangely the same. Because the new note sounds the same-but-different, it feels reasonable to name it after the rst, so this is another, higher A. The distance or interval between two notes related in this way is an octave, and the strange kinship between the two notes is called octave equivalence, a phenomenon that almost all human beings experience and one of the essential building blocks of almost all music.

Long ago, we started nding notes to spread through the space within the octave. We could have chosen any number of notes but most cultures went for 5, 6 or 7 and most probably chose their sets of notes intuitively, as they might have picked owers - because they liked them and the ways in which they related to each other. In ancient Greece, however, Pythagorus noticed that it isn't only the simple 2:I proportions of the octave that please the ear. Two notes whose frequencies are related in the proportion 3:2 are also particularly pleasing and produce what we now call a Perfect Fifth, (C & the G above it, for instance). 4:3 is a Perfect

A string that plays the A below the middle C on a piano vibrates 440 times a second. We say that it has a frequency of '440 cycles per second (cps), or '440Hz' (Hertz). Halve the length of that string and it will vibrate 880 times a second, exactly twice as fast as before.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

8 / 85

Fourth (C to the F above). 5:4 is a Major Third (C to E). Th e s e i n t e r v a l s a r e r e m a r k a b l y consonant. What the Greeks had noticed was that simple mathematical relationships between frequencies please us, particularly when the notes are played together. As harmony began to interest European musicians more and more, they tried many ways of tuning the intervals within the octave. They also devised the chromatic set, a pool of 12 notes from which a variety of 7-note scales could be extracted; many early instruments couldnt play all the possible scales, but an instrument that was designed to play the chromatic set could - in theory, at least. A problem, however; because the 12 notes werent evenly spread through the octave, some scales were more perfectly t u n e d t h a n o t h e r s . Th i s h a d i t s advantages; composers could choose a key for its particular avour, sweet or sour. But it had its disadvantages; keys including more than four ats or sharps were so sour that they were barely usable. This hampered composers who wanted to write music that changed key freely in the course of a piece, and there was a growing interest in this possibility. Slowly, we gravitated towards a tuning system that had been around since Galileo's father had advocated it in 1581; equal temperament, twelve notes spread at mathematically calculated, equal intervals across the octave. Now, the frequency relationships between any two adjacent notes were identical. We had striven for intervals of pristine mathematical and aural perfection but now made a compromise, trading some slightly iffy intervals for the possibility of writing music that could move freely between 12 acceptably tuned keys, each one of them using only a selection of notes from the full set, and each one tuned exactly like the others. This was a move which liberated composers to write ever richer and more exotic harmonies and to take their listeners on safari through many of the 24 available major and minor keys - and then beyond! The incredibly fertile but slightly sour set of twelve notes that we have inherited is the equally tempered chromatic scale or chromatic set.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

9 / 85

the CHROMATIC SET

So - the chromatic set contains the 12 equally spaced notes available to us on most Western instruments. Arranged in ascending or descending order the 12 notes of the chromatic set become the chromatic scale. The distance, or interval, between each of these notes and its nearest neighbour is called a semitone (a frequency relationship of roughly 16:15) As we have tended to use only seven of these 12 notes at a time, it has made practical sense to name the 12 notes using only seven letter names. Seven of these have simple letter names, but notice that they arent distributed evenly through the twelve (well, they couldnt be . . . ).

The 7 notes with simple letter names are called naturals - A natural, B natural and so on. Most of the naturals are a tone apart (i.e. two semitones), but notice that A & B are only a semitone apart, and so are E & F. The 5 remaining notes are named after the naturals that they sit between and this means that they can each have two names. The note between A & B, for instance, can be called A# (A sharp - which simply means the note a semitone higher than A) OR it can be called B (B at), meaning the note a semitone lower than B.

We say that A# is the enharmonic equivalent of B. Similarly; F# = G, G# = A, C# = D, D# = E

Heres the full chromatic set written out twice, with sharp names on the top row, and ats on the bottom.

A A

A# B

B B

C C

C# D

D D

D# E

E E

F F

F#

G# A

A A

G G

And here are the two versions written in standard notation -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

10 / 85

The sign that you see written before the naturals () is a natural sign. As you would expect, its used to indicate that the following note is a natural, and its use is necessary here to cancel the at sign on the note before it. Apart from that, only the names are different; in every other respect these two chromatic scales are identical.

accidentals

Sharp signs #, at signs , and natural signs are all called accidentals when used just before a note. They all apply to the rest of the bar that they appear in but not beyond. (Ive never met anybody who knows why they are called accidentals, which they clearly arent.)

rst INTERVALS

OCTAVE, SEMITONE & TONE

Just to recap - the differing distances between notes are called intervals, and each interval has a name. We will describe all of these possibilities later, but for now you need to know about the following three:

octave

the interval between two notes whose frequencies are related in the ratio 2: I - two As or two C#s for instance. the interval between any two adjacent notes in the chromatic set, (E & F, for instance, or F and F#), and two semitones, the interval between A & B or E & F#.

semitone

tone

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

11 / 85

SCALES

A Scale is a collection of notes written or played in ascending or descending order, starting and nishing on the tonic, the home note for the piece. It provides the basic raw materials from which the melody and chords of a piece can be made. There are hundreds of different scales in use around the world and each one has its own avour and offers certain musical possibilities. Some scales offer exquisite melodic possibilities, for instance; others are a source of interesting chords and allow us to create complex harmonic systems. Most western scales and modes are heptatonic, meaning that they use only seven notes. Its possible to have scales with more or less than seven notes and pentatonic scales (ve-note scales) are particularly common. Here are some scales from various cultures, with the chromatic scale at the top and the other scales all starting on the same note so that you can compare them easily.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

12 / 85

In reality, Indonesian, Middle Eastern and many other scales use notes that simply aren't available in equal temperament, so some of the scales written above are approximations. In almost all Western classical, popular & folk music, however, the contents of almost all scales are now selected from the equally tempered chromatic set.

the MAJOR SCALE

The Major Scale is undoubtedly the best-known and probably the most used of all heptatonic scales. Its crucial to understand how the major scale is built, if only because we dene all other scales by comparing them with the Major Scale.

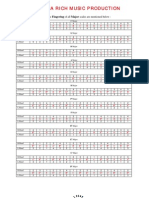

A major scale can start on any note, but then follows this xed, dening sequence of intervals tone - tone - semitone - tone - tone - tone - semitone

Here, for instance, is the C major scale.

and here is an A at major scale - the sequence of intervals is the same.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

13 / 85

TETRACHORDS

In common with other Heptatonic (seven note) scales, the Major scale has a lower tetrachord and an upper tetrachord, its rst and last four notes. Notice that the two tetrachords of a major scale have identical tone-tone-semitone structures, with a gap of one tone between the two tetrachords.

Notice, too, that the Upper Tetrachord starts on the fth step of the scale. This will become very signicant . . . . .

KEY SIGNATURES

There are only 12 major scales, one starting on each step of the chromatic scale. Each one of them uses a unique selection of notes. To indicate which scale you should use, notated music almost always includes a key signature, a bunch of up to 7 sharps or ats placed at the beginning of a piece and then at the beginning of every subsequent line. Some key signatures contain sharps, some contain ats. No major or minor key signatures contain both. Some examples -

The last key signature above includes just one at on the middle B line. In practice, this means that you should play B every time you see a B, regardless of which B it is. The third key signature tells you to play F#, C#, G# & D# and the same rule applies - play these notes every time you see an F, C, G or D. Notes not mentioned in the key signature are assumed to be naturals. This is a really helpful system. It saves a lot of pointless repetition of at and sharp signs in the notation. More importantly, it forwarns the experienced player that they will be using a familiar collection of notes - a G major scale, for instance.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

14 / 85

the 12 MAJOR KEYS

To understand how the key-signature system works, and how the 12 major keys are related, it's worth looking again at the diagram showing the two matching tetrachords of the major scale - (in passing, notice that, as the C major scale is made up entirely of naturals, there is no need for a key signature.)

As the Upper Tetrachord of this C major scale has the same structure as the Lower Tetrachord, it is possible to use it as the Lower Tetrachord of a new major scale starting on G - a G major scale -

In order to keep the tone - tone - semitone structure in the new Upper Tetrachord, the seventh step of this new scale needs to be an F# rather than an F The F# is the only note in this scale that isnt a natural, so we simply write a key signature with one sharp - F# - and this tells the player to play F# when they see any F in this piece (not just the F on the top line of the stave).

The new Upper Tetrachord that this process has produced can be used to begin yet another major scale. It starts on D, so its D major -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

15 / 85

The F# in the Lower Tetrachord is still needed, of course, but, as before, the new 7th step (C) now has to be sharpened to maintain the major-scale structure, and the new key signature has to have an F# and a C# -

We can carry on this process until we run out of sharps. Each new scale will start a fth higher than the last and will include one new sharp at the end of its key signature. Here are the major keys with sharps in their key signatures. Notice that the sharps are always written in the order in which they have been added.

You may have noticed that, as you create each new scale, the sharp that is added at the end of the key signature always refers to the new 7th step. It follows that: The last sharp in a major key-signature is always a semitone below the tonic. The order in which the sharps appear and are written is F# C# G# D# A# E#* B#*

(Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle) Notice also that each new sharp is 5 steps above the last.

* E# is an alternative name for F , and B# the alternative name for C . If this is a surprise, remember that sharp simply means a semitone higher than, and then it makes sense.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

16 / 85

MAJOR KEY SIGNATURES WITH FLATS

Sharp key signatures can only be used for seven of the twelve keys. Flats are needed for the rest. Key signatures with ats work in a similar fashion to sharp signatures, but each key starting a fth below the last, and each one adding one more at to the key signature. Here are the 'at' major key signatures starting from C major again -

Usefully (and logically) the order of key signature ats is the reverse of the order of sharps B E A D G C F

(Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles Father) Notice also that each new at is 5 steps below the last, and that the rst four ats conveniently spell BEAD. In at key signatures, the next-to-the-Iast at names the tonic; For instance, if the key signature shows B, E & A, its the Eb that appears next to last, so you're in E major. Look at the at key signatures above to check this out.

Youll spot that F major doesnt have a next-to-the-last at - youre just going to have to remember that one. You may also have noticed that there are now apparently 15 key signatures this is because F# major has appeared twice - once as F# major, and once as Gb major, which contains exactly the same notes by different names. B major has also appeared as Cb, and C# as Db.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

17 / 85

MINOR SCALES

the NATURAL MINOR Scale

The second best known scale is the minor scale. There are in fact various versions of the minor scale and the simplest is the Natural Minor. Starting on C, it goes like this:

You'll notice that the rst, second, fourth and fth notes are the same as in the C major scale but that steps 3, 6 & 7 are attened - a semitone lower than their Major scale equivalents. So, as we dene all scales by comparing them with the major that would start on the same note, we can say that the Natural Minor scale has a at 3, 6 & 7. You may have also noticed that C natural minor contains the same notes as E at major. It will therefore have the same key signature -

Natural Minor scales can start on any note, of course -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

18 / 85

MELODIC & HARMONIC MINOR SCALES

In practice, many pieces in the minor dont simply use the seven notes of the natural minor scale. Greensleeves is a perfect example of this. Here it is in A minor, which has no key signature -

Notice that the sixth and seventh steps of the scale (F and G naturals) often appear as predicted by the key signature, but that sometimes accidentals are used to indicate that F# and G# should be used instead, despite the fact that F# and G# are the sixth and seventh steps you would expect to nd in A major. This is absolutely typical of a huge number of minor key pieces; the major and minor sixth and seventh steps are used interchangeably, the major versions being indicated with accidentals. This may have arisen because musicians found it effective to accompany minor key melodies using a couple of chords which also include the major sixth and, more particularly, the major seventh steps. In order not to clash with these chords, the melody sometimes has to include a major six and seven, too. In Greensleeves, for instance, the G#s (the major 7s) are almost always used at a point where an E major chord (E - G# - B) is sounding; a melodic G would clash. So why is the sixth step also altered? Sometimes to accommodate a chord with a sharp 6 in it, but, as often as not, its altered in combination with the seventh step, simply to avoid large leaps in what would otherwise be a smoothly owing phrase.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

19 / 85

In an attempt to rationalise this rather uid situation, theorists have constructed the rigid harmonic and melodic minor scales -

The Harmonic Minor

scale is notated with a sharpened seventh step. This scale is regarded as being the source of the chords used in minor key pieces. In contemporary use, this isnt quite true. Nevertheless, for reference, here is A harmonic minor.

(As this scale really only has a theoretical function, why do players of melody instruments practice it so diligently, except to pass exams?)

The Melodic Minor

scale is notated with the major sixth and seventh steps in the rising version of the scale and the attened sixth and seventh steps indicated by the key signature in the descending version. Accidentals are needed in both directions to introduce and then cancel the major 6 & 7.

There is a myth that the major 6 & 7 steps are generally used when melodies are rising, and that the at 6 & 7 are used when melodies are falling, and that this justies the way that the melodic minor is both notated and practised. In reality, the different sixth and seventh steps are used equally in rising and falling melodies, and for the harmony-related reasons given above. Practising the melodic minor as it is usually notated is valuable, but it would surely be more realistic to practice both versions in both directions.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

20 / 85

RELATIVE MAJOR & MINOR KEYS

Here are the key signatures for all twelve possible minor keys, each one starting ve scale steps above the last, but leaving out A# minor, Eb minor & Ab minor, for which there are already enharmonic equivalents. It should look familiar.

You may have identied that this sequence of minor key signatures is essentially the same as the sequence of major key signatures that you came across earlier. Theres nothing obscure about the reason for this: every major scale contains the same basic set of notes as one minor scale. As these these pairs of scales use the same notes, they use the same key signatures and they are considered to have an especially close relationship C major and A minor form one such pair, so we can say that C major is the relative major of A minor, and that A minor is the relative minor of C major. Notice that A is the sixth step of the C major scale.

This is true of all pairs of related scales The tonic of the relative minor is found on the sixth step of the major scale (or three semitones below the tonic). The tonic of the relative major is on the third step of the minor scale (three semitones above).

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

21 / 85

For reference, here's a set of key signatures with relative minors above and relative majors below. .

MINOR KEY SIGNATURES

Its really useful to be able to work out key signatures. Its even better just to know them - there are, after all, only 12 major and 12 minor keys. At the very least, learn all those up to four sharps and ats. There are some handy rules, however, that can be used in various situations. In Parallel major and minor scales (pairs of scales which start on the same note, like C major & C minor) the minor scale has three more ats than the major (& it follows that the relative major has three more sharps than the minor).

(This may need a little explanation. If the major key has sharps in it, the extra three ats in the parallel minor will effectively cancel three of the sharps. If there were four sharps, for instance, three will be cancelled and you will be left with one. If there was only one sharp, one of the new ats will cancel it and the remaining two ats will appear in the key signature. Have a look at the chart of relative majors and minor key signatures if you need to clarify this to yourself.)

Also The tonic of a minor scale is two tones above the last at or one tone below the last sharp of the key signature.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

22 / 85

SCALE STEP NAMES

Before moving on to talk about key relationships, we need to give new names to the steps of the scale. These names will be useful when you come to read about chords in part two, as well.

ABSOLUTE & RELATIVE NAMES

There are various ways of naming notes. Some of them are absolute; a C is always a C, for instance. In most kinds of music, however, there is also a way of naming notes which we can think of as being relative, a way of identifying the position of a note within the scale and its relationship to the other members. For instance, each scale note has a relationship to the tonic and a position in the scale. It follows that the second step of a scale can be called just that step two. The rest of the notes could be similarly named steps three, four, ve and so on. Another relative set of names that you may have come across is doh-re-mifah-so-la-te-doh. In this sol-fa system, the rst step of the scale is doh regardless of what key you are in, and re is the second step, and so on. (Unless youre French . . . . . . . ) Indian music uses a similar set of names Sa - re - ga - ma - pa - dha - ni - sa. These names are ne in many situations but Western musicians have found it useful to use both an absolute name (C, F# etc.) and a relative name for each note, and have favoured a set of names that recognises the signicance of each scale step; in many ways, western music has a hierarchical structure, and these names recognise that -

STEP NAMES

The rst step of the scale, the most signicant of all, to which all the others relate, is the TONIC. I have already hinted that the fth step of the scale has particular importance and a particularly strong 3:2 frequency relationship with the tonic. It is called the DOMINANT.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

23 / 85

The fourth step (which could also be thought of as the note 5 steps below the tonic) has a similar but slightly weaker relationship to the tonic. It is called the SUB-DOMINANT. The third step of scale is halfway between the two poles of the scale, the tonic and the dominant, and it is called the MEDIANT. Combined with the tonic and dominant, it completes the tonic chord of the key. The sixth step of the scale is halfway between the tonic and the sub dominant below it. It is called the SUBMEDIANT. Combined with the tonic and sub-dominant, it completes the subdominant chord.

That leaves just two more steps -Step two is tthe note just above the tonic and is called the SUPERTONIC. Step seven often creates a desire for the tonic in the listener and is called the LEADING-NOTE.

Here are the names applied to the notes of a C major scale, but remember that they can apply to the steps of all major & minor scales, and the modes that we will discuss later.

Step No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Name tonic supertonic mediant subdominant dominant submediant leading note upper tonic

Sol-fa Doh Re Mi Fa Soh La Ti Doh

Indian Sa Re Ga Pa Ma Da Ni Sa

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

24 / 85

KEY RELATIONSHIPS

Relative major & minor

Youve already seen that pairs of major and minor scales which share the same note-content are are considered to be closely related - we say that C major is the relative major of A minor and that D minor is the relative minor of F major, and so on.

Parallel keys

Other pairs of scales are also considered as being related. Major and minor keys starting on the same tonic, for instance, are called parallel keys. We say that C Minor is the parallel minor of C major. Similarly, D major is the parallel major of D minor. If a piece modulates (changes key) from A major to A minor, we can say that it has moved to the parallel minor. It is also common to talk about moving to the tonic minor or the tonic major - it means the same thing.

Dominant - subdominant etc. . . . .

If a piece modulates from C major to G major, we say that it has modulated to the dominant, because G major is the scale / key built on the dominant of C major. Similarly, a shift from C to F major would be a modulation to the subdominant. A shift from C to E would be a modulation to the mediant . . . . and so on.

Close & distant relationships

Some keys are more closely related than others. On the whole, keys are considered to be mostly closely related when the two scales share a tonic or key-signature. Moving to the dominant involves changing only one note, so that relationship is also considered to be a close one. The less that scales have in common, the more distantly related they will be.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

25 / 85

THE CIRCLE OF FIFTHS

If you move from any key to its dominant, and then from the new key to its dominant, and so on, you will eventually nd that you have moved through all twelve possibly keys and returned to the one you started on. This sequence of keys is called the Circle of Fifths because each new tonic is a fth above the last (a fth being the interval between the tonic and fth step of a major or minor scale). This concept has been very important in tonal music, and can be applied to key relationships and to chord sequences (which well look at in much more detail later). Here is the Circle of Fifths for reference -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

26 / 85

OTHER SCALES

the CHURCH MODES

We have discussed the two best-known Western scales, and these are the ones that most theory courses restrict themselves to. However, many other scales used to be used in Europe, including a set of modes. They were used less and less as harmony became the driving force behind our music but they came back into use in many twentieth and twenty-rst century genres. Their use in folk music never declined. The modes in this set have something in common; they each contain 5 tones and 2 semitones, and the 2 semitones are in every case a fth apart. Apart from the Ionian and Aeolian (which are the same as the Major & Natural Minor), the Dorian, Mixolydian and Phrygian modes are the most frequently encountered.

Here is the full set -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

27 / 85

As with all other scales, these modes can start on any note. There is an allnaturals version of each of these modes, and you might like to experiment with them all -

Name

IONIAN MIXOLYDIAN DORIAN AEOLIAN PHRYGIAN LOCRIAN LYDIAN

Content

all-naturals version starts on . .

C

7 3 & 7 3, 6 & 7 2,3,6 & 7 2, 3, 5, 6 & 7

#4

G D A E B F

These modes are associated with (and help to characterise) different styles and have been heavily used in recent music. The Mixolydian, Dorian and Aeolian, for instance, are heavily associated with folk and popular styles, but also modal jazz. The Phrygian is instantly recognised as the Flamenco scale and gets heavily used in Heavy Metal. The Lydian is beautiful but quite rare and associated mainly with East European folk styles. The Locrian is so strange and unstable its rarely used at all.

MODAL KEY SIGNATURES

Key signatures for these modes are no different from major and minor key signatures and simply recognise the pitch content of the piece. Having applied the key signature, there is sometimes confusion about how to name the tonality of modal pieces. The rst step is to identify the tonic by listening to and examining the piece the closing chord and note are a fairly reliable guide. If the tonic is E, then the piece is in 'E something'. The second step is to ask which mode the rest of the notes in the piece make when arranged above E - when you've identied the unique structure of the Dorian or the Phrygian, then you can say that the piece is in 'E Dorian' or 'E Phrygian'.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

28 / 85

PENTATONIC SCALES

Five-note (pentatonic) scales are common and two of them have become so well known that we tend refer to them as The Major Pentatonic and The Minor Pentatonic.

The Major Pentatonic

contains steps 1, 2, 3, 5 & 6 of the major scale. Here is C Major Pentatonic -

This scale crops up in music from Scotland to China, Africa to the Andes. You can play F# Major Pentatonic entirely on the black notes of any keyboard.

The Minor Pentatonic & The Blues Scale

is also very common, and it contains a 1, b3, 4, 5 & b7. Here is A Minor Pentatonic

Notice that it contains the same notes as C Major Pentatonic.

Many musicians think of this as The Blues Scale, but a fuller version of the Blues Scale will include a chromatic link between the 4th & 5th -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

29 / 85

WHOLE TONE & OCTATONIC / DIMINISHED SCALES

There are too many other scales to mention them all. As far as Western music goes, the following two have been much used both in 20th century classical music and jazz improvisation. The rst is the

Whole-tone scale,

most famously used by Claude Debussy. Every interval in the scale is a tone, and it has a curiously centreless, oating quality. This is rarely notated with the key signature - just use accidentals as necessary.

The other is the

Octatonic / diminished scale

an eight-note scale made up of alternating tones and semitones. This appears in the work of many composers (Messiaen, for instance), and is often used by jazz players as the basis of improvisation against diminished chords. Again, a key signature is not appropriate (or possible).

KEY SIGNATURES WITH SHARPS & FLATS COMBINED

Some scales from other musical cultures can only be notated with key signatures that combine sharps and ats. Heres an Indian scale -

ATONAL MUSIC

Much 20th-century music is atonal, meaning that it is not in any key and usually indicating that all 12 notes of the chromatic set are used freely or equally in the music. A key signature makes no sense in this situation, so accidentals must be used throughout the music.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

30 / 85

In tonal music, accidentals only apply for the remainder of the bar that they rst appear in. This convention also applies in some atonal music, but most atonal composers notate their music on the understanding that accidentals only apply to the note that they precede. Its usually clear from the context which of these conventions applies.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

31 / 85

INTERVALS

You have already come across the octave, tone & semitone. There are other intervals, of course, and it would be easy enough to list their sizes and names, but its important to recognise that intervals are much more than spaces between notes. Each one has its own character, value and psychological and emotional impact; styles are dened by the use of certain intervals, forward motion is achieved by the shifting between dissonant and consonant intervals, harmonic systems are constructed around them, the emotional value of each one has been explored across time and disparate cultures. Intervals are really important - well come back to some of their more interesting qualities later..

Harmonic & Melodic Intervals

Intervals can be harmonic or melodic, depending on whether the two notes are heard simultaneously (as part of a harmony) or one-after-the-other (as part of a melody). Harmonic and melodic intervals of the same size have the same names.

INTEGER NOTATION

The simplest way to name intervals is simply to say how many semitones each interval spans. In this system, C to C# is a 1 C to D is a 2 and so on . . . . . . . Falling melodic intervals can be notated with a minus sign, so C up to E C down to E = = 4 -8

This system of naming is particularly appropriate for atonal or post-tonal music - it makes no sense to talk about minor thirds, major sixths and so on when describing music which is neither major nor minor. This is also the way that MIDI programs such as LOGIC identify intervals; if you want to transpose some midi information youll be invited to say how many semitones you want to raise or lower what you have recorded.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

32 / 85

Youll nd a chart comparing numeric intervals with their tonal equivalents on page 00.

PITCH CLASS INTERVALS

In music the term pitch is used to identify a unique note - middle C, for instance, but not the one above it. By contrast, a pitch-class identies all notes of the same name - the pitch-class C means all Cs, G# means all G#s and so on. Pitch-class Intervals measure the shortest distance between two pitch-classes, rather than the actual distance between specic pitches. It follows that 6 is the largest pitch-class interval that is needed. The most appropriate application for this system is to serial music.

INTERVALS IN TONAL MUSIC / Diatonic Intervals

The above makes perfect sense in certain music, but is still true that most of the music that we listen to and perform is tonal, and there is an established system for naming intervals embedded in that system.

Number & Quality Each interval is named in part after the number of scale steps that it spans, always counting from the lowest note. An interval between C and E, for instance, is a third because it spans three letter-names - C, D & E. A to E spans A, B, C, D & E so it is a fth. A to G is a seventh.

This is a simple rule but you may have already spotted a problem. C/E is a third because it spans C, D & E. However, C to E is also a third, because it too spans three scale steps. The two intervals are clearly different, so we

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

33 / 85

need to say what kind of thirds these are to avoid confusion; we have to identify the quality of each interval. Here are some straightforward and then increasingly obscure rules about the full naming of intervals.

MAJOR & PERFECT INTERVALS

If the upper note of an interval can be found in the major scale built on the lower note, the interval is either a Major interval or a Perfect interval. Here are all the possible intervals in C major. Notice that, where you might have expected to nd a major fourth and a major fth you nd a Perfect Fourth and a Perfect Fifth.

MINOR INTERVALS

If you atten the upper note of any of the four major intervals, you produce a

minor interval. This means that we can have a 'minor second', even though it never actually occurs in a minor scale. (The minor third, sixth and seventh do appear in the minor scale.)

DIMINISHED INTERVALS

If you atten a minor interval or a perfect interval, the result is a diminished interval. It's been necessary to notate some of these with 'double ats' and these do what it says on the can so A!, for instance, turns out to be another way of naming a G.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

34 / 85

AUGMENTED INTERVALS

If you sharpen the upper note of a major or perfect interval, the result is an augmented interval. As with some of the diminished intervals, some of these are very uncommon.

You'll have noticed that what is essentially the same interval can have two or more names - compare a Minor 3rd and Augmented 2nd, for instance.

COMPARISON CHART

For reference, here is a chart comparing some ways of naming intervals No. of semitones 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pitch-class intervals 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Diatonic name

Unison / Perfect Unison Minor Second Major Second Minor Third Major Third Perfect Fourth Augmented Fourth / Diminished Fifth Perfect Fifth Minor Sixth Major Sixth Minor Seventh Major Seventh Octave / Perfect Octave

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

35 / 85

CONSONANCE & DISSONANCE

Some intervals are noticeably more consonant than others - easier on he ear, if you like. By contrast, some intervals are dissonant - harder on the ear. These terms are relative; some people have a lower dissonance threshold than others, and feelings about what intervals are consonant have changed over time. The octave is regarded as being the most consonant interval and, if you remember from the very beginning of this document, it is the interval with the simplest mathematical relationship between its two frequencies (2:1). The perfect fth and perfect fourth come next with frequency relationships of 3:2 and 4:3. Different authorities apply different criteria when evaluating the relative consonance and dissonance of some of the remaining intervals. Few, however, disagree that the next group still sound relatively consonant major third minor third major sixth minor sixth (5:4) (6:5) (5:3) (8:5),

and that the most dissonant intervals are major second minor seventh minor second major seventh diminished fth (9:8) (16:9) (16:15) (15:8) (45:32)

Notice that the more consonant intervals feature frequency relationships containing lower numbers.

INVERSIONS

If you take the lower note of any interval and move it up an octave, you have inverted the interval. If you invert a second, the result is the seventh. If you invert a third, the result is a sixth. Similarly, a fourth becomes a fth, a fth a fourth, a sixth a third and, nally, a seventh becomes a second.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

36 / 85

That was a very general statement. What about minor thirds, major thirds, minor sevenths etc? The rule is very simple; When you invert intervals The numbers add up to 9, and Perfect intervals remain Perfect. (P) Major intervals (M) become Minor (m) Minor intervals become Major. Augmented intervals (+) become Diminished (d) Diminished intervals become Augmented.

INTERVALS - THEIR CHARACTERS

Each interval has certain qualities in common with its inversion HARMONIC INTERVALS (when two notes are played simultaneously) Perfect fths and fourths, for instance, are generally thought to sound stable, spacious, clear, even noble. Thirds and sixths are also thought to be stable, but less stable than fths and fourths, also thicker, sweeter and richer. Seconds and sevenths are considered to sound unstable and relatively dissonant. Minor seconds & major sevenths are considered to be the most dissonant. A special mention for the diminished fth / augmented fourth, which is so unstable and dissonant it used to be known as the devils interval and was even forbidden at one time. This interval famously characterised what most people regard as the most dissonant, least tonally stable music of the 20th and 21st centuries.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

37 / 85

MELODIC INTERVALS It isnt far-fetched to suggest that when we hear the two consecutive notes of a melodic interval, we nevertheless relate them harmonically in our minds, and its certainly true that melodic intervals have the same qualities as their harmonic equivalents; melodic perfect fths still suggest solidity and boldness; diminished fths still feel strange, spiky, in need of resolution. Some intervals seem to inspire particular expressive associations; a falling minor third is usually considered sad, while a rising major sixth is generally thought to sound optimistic and aspiring (the opening notes of If I ruled the world . . . make an obvious example). . . . . large & small Its also possible to generalise about the size of melodic intervals. A melody consisting entirely of small intervals will inevitably have a more owing and less abrasive character than one made out of relatively large leaps. Large leaps can be very striking, underline moments of high emotion and markedly raise the energy level - a lot of conjunct motion will produce the opposite effects. Many composers successfully exploit and contrast these two kinds of motion, even within one phrase.

HARMONIC INTERVALS & MUSICAL STYLE

Different harmonic intervals have characterised the music of different periods and its interesting that, in Europe at least, we have gradually accommodated and at times favoured the more dissonant intervals. Heres an excerpt from a little mediaeval piece for two instruments or voices. Harmonically, it is typical of its period. The numbers show what intervals occur between the parts, and a quick glance will tell you how favoured octaves, fths and fourths are, particularly if you look at the intervals which are rhythmically stressed.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

38 / 85

Heres part of a baroque duet by Telemann, historys most prolic composer. There is now a very marked shift to a texture saturated with thirds. Thirds, of course, are the building blocks of major and minor chords, and Telemanns music was conceived in terms of chord progressions, so this is no surprise . . . .

Finally, heres some early 20th-century music by Schoenberg.

Now the picture is not so clear. Schoenberg still uses thirds, but the less stable minor thirds, and he freely uses and emphasises more dissonant, unstable intervals like seconds, sevenths and augmented fourths. While the textures of popular music were to remain saturated with the sweetness and harmonic stability of thirds, a huge amount of 20th Century classical music was to be avoured with the peppery, unstable intervals that Schoenberg had favoured. Its clear that the use of different harmonic intervals lends markedly different avours and helps to characterise different styles, even different periods of music. It also partly determines what is possible in each periods music.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

39 / 85

TRANSPOSITION

If you start singing a favourite tune now, the chances are that you will pitch it higher or lower than the last time you sang it. Even though you start the tune on a different note, the melody remains recognisable because the intervallic structure of the piece is retained; you still move down a major third, up a tone, down a perfect fth etc. regardless of which note you started on. This, for example -

is the same tune as this -

Youll note that the second version of the tune starts a perfect fourth higher than the rst - in fact, every note in the second version is a perfect fourth higher than the corresponding note in the rst. We say that the tune has been transposed up a perfect fourth. The act and technique of moving music in this way is called transposition and whole pieces of music can be transposed; so long as every note in Beethovens 5th Symphony is raised by a semitone, most listeners wont notice the difference. (This has actually happened; in Beethovens time instruments were tuned considerable lower than they are now.)

The ability to transpose music is an essential skill for any arranger or composer. You may have a vocalist who can sing a piece more effectively in a different part of his or her range, for instance - the instrumentalists need to transpose their parts to suit. In another situation, you may want to repeat a section of a piece but in a new key. If you are writing or arranging for transposing instruments such as clarinets, saxes and French Horns, you need to know how to transpose their parts so that they sound at the right pitch. There are various ways you can approach this problem -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

40 / 85

TRANSPOSITION TECHNIQUES

1 Interval by interval

This is perhaps the most laborious transposition method, but sometimes necessary, particularly in music without a key signature. When you have decided how far you need to transpose the music, move every note up or down by the same interval. Here, for example, the rst melody is transposed up a tone, and then down a major third.

Another approach is to decide on the new rst note and then copy the interval sequence from the source melody. In this case, thats down a dim5, up a m3, down a dim5 and so on. Using both approaches allows you to double check that you havent slipped up at any point. And - of course check the results by ear.

Transposing from one key to another.

The most likely transposing job will involve moving material from one key to another: D major might suit your vocalist better than C major, for instance, or a piece might simply be easier to play in C rather than C#. This process is rather easier than the previous one 1) Work out what your new key needs to be. Insert the appropriate key signature in your new score. 2) Work out how many scale steps up or down you need to move from the original version to the transposed version. (E up to G would be a third, and so would Eb to G#). 3) Move every note that number of steps. The new key signature takes care of the intervallic structure . . . Job almost done -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

41 / 85

Heres an example, a tune in E minor thats needs transposing up into G minor:

After inserting the new key-signature (two ats), simply compare the two tonics, in this case E & G. They are a third apart (and it doesnt matter what kind of third). Now slide all the music up a third, (from any space to the space above, or from any line to the line above). The original piece included some accidentals. If you simply copy them across -

it might or might not sound right, and the E# in this example doesnt. You clearly need to think of the accidentals in a different way in this context. In the original tune, the accidentals told you that the C and two Ds should be played a semitone higher than the notes implied by the key signature (i.e. that you should play a C# & D# instead of C & D). When you make the transposition, you need to make sure that the same is still true. In the G minor version, the key signature implies an Eb and an F natural, and as the notes a semitone higher than those are E natural and F#, those are the notes that you now need to notate. The correct transposition is therefore -

Notes for computer users: In Logic etc. you can ask the program to transpose your midi recordings up or down by a specied number of semitones - refer to the comparison chart a few pages back to translate interval names into numbers. In dedicated notation packages like Sibelius, transposition works in a number of ways and you need to be careful which method you use. For instance, if you select a group of notes in Sibelius and then use the arrow keys to raise or lower them, the notes will be moved up or down a space or line at a time, but are unlikely to retain their intervallic structure unless you are transposing by an octave.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

42 / 85

Alternatively, you can select notes and then use the Transpose function. At this point you will be offered the choice to 1) transpose your material up or down by an interval that you specify, or 2) transpose the material to a new key of your choice (assuming that you are creating a score in a key). Both of these methods will retain the intervallic structure correctly, but the notation might or might not be grammatically correct (particularly as regards accidentals) so you will still need to check and edit the music.

Transposing chord symbols

Easy. Transpose the roots of the chord symbols consistently. The sufxes remain unchanged. For instance: Cmaj7 | Fm9 |E |D7 ||

when transposed up a perfect fourth, becomes Fmaj7 | Bbm9 |A |G7 ||

Transposing Instruments

For reasons to do with the historical development of various wind instruments, we have a strange situation where an alto saxophone player might nger and play a written C, but produce the sounding Eb a major sixth below. On a tenor sax, the same ngering and notation will produce a Bb and octave and a tone below. This isnt quite as crazy as it may sound, but it is a situation were stuck with so . . . . .

There are a number of transposing instruments, nowadays mostly in Bb (meaning that a written & ngered C produces a sounding Bb) or in Eb (meaning that a written and ngered C produces a sounding Eb). The commonest transposing instruments are Clarinet (Bb - sounds a tone lower than written) Bass clarinet (Bb - sounds an octave + tone lower than written)

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

43 / 85

Soprano sax (Bb - sounds a tone lower than written) Alto sax (Eb - sounds a major sixth lower than written) Tenor sax (Bb - sounds an octave + tone lower than written) Baritone sax (Eb - sounds an octave + major sixth lower than written) Trumpet and Cornet (Bb - sounds a tone lower than written) French Horn (in F - sounds a perfect fth lower than written) Cor anglais (in F - sounds a perfect fth lower than written) I should also mention that some instruments transpose at the octave the guitar, for instance, sounds an octave lower then written, while the glockenspiel sounds an octave higher.

In order to cope with this situation, the arranger / composer has to transpose the players parts to compensate for this discrepancy. For instance, a Bb clarinet sounds a tone lower than written, so you need to compensate by notating its music a tone higher than you want to hear. Write a D if you want to hear a C, a G# if you want to hear an F#. Just as importantly, youll need to give the transposing instrument its own key signature - write the clarinets music in the key of D major if you want to hear C major, and so on. Played by a clarinet, soprano sax, trumpet or cornet, this E major scale -

sounds like this, a D major scale -

Notes for computer users If you set up your program correctly, you will nd that parts are automatically transposed, along with their appropriate key signatures etc.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

44 / 85

MECHANICAL TRANSPOSITION

Guitars + Capos . . . .

The guitarists capo is a clamp placed on the guitar neck which effectively shortens the ngerboard; a capo placed in the second fret will raise the pitch of the guitar by two semitones. If you now nger and play a C major chord on your shorter, higher pitched instrument, it will sound as a D major chord. The guitar has effectively become a transposing instrument in D. By placing the capo in the third fret, youll make it a transposing instrument in Eb, and so on. This is very useful if youve learned a piece in one key and want to transpose it quickly into another. There will also be situations where you want to use the capo to improve or change the sonority of the guitar, or to allow you to use easier or more effective voicings. If the guitar is to sound in the same key as any other instruments, you will have to transpose its part in order to compensate for the effect of the capo. For instance, if your piece is in Eb major, an awkward key for a guitarist, you can put the capo on the third fret. This raises the pitch of the guitar by three semitones / a minor third. If you then transpose the guitar music down a minor third to compensate for this, you nd yourself reading & playing in the friendlier key of C major, but still sounding in Eb. So -

CAPO 3 sounds -

|| C

|G

|F

||

|| Eb

| Bb

| Ab

||

. . . . and Digital Keyboards Almost all digital keyboards have a transpose function which is even more exible than the guitarists capo because it will transpose down as well as up. Control of this varies, but typically you need to work out how many semitones you want to raise or lower the music by and then, in combination with a transpose button, press the key positioned the same number of semitones above or below middle C. (Refer to the keyboard instructions).

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

45 / 85

HARMONY

Music can be conceived as having a horizontal axis and a vertical axis. Melody and rhythm take place in the horizontal dimension. Harmony is what happens in the vertical axis. Any vertical slice of music containing more than one note is considered to contain harmony, and there is no limit to the number of pitches that might be present in such a slice. The resulting chords will have a variety of characteristics, and these characteristics will help to dene the style, period and genre of the piece. Jazz, for instance, is typically saturated with more complex and more ambiguous chords than would be typical of Mozart or recent rock music; Stockhausens music is typically more dissonant than Debussys. Most styles of music, then, have distinctive vertical characteristics. While the kinds of harmonies permitted or favoured in a particular style might help to dene it and might indeed be crucial to its overall effect on the listener, they are not, however, necessarily structural elements. . . . . Between about 1650 and 1900, however, European musicians developed a number of styles in which the harmonic aspects were of primary structural importance. This Period of Common Practice was, if you like, the period of the chord progression, of major and minor keys, of chords used in a hierarchical relationship, of harmonic journeys to and from the tonic chord and from one key centre and another, so creating a sense of movement and a dening shape for each piece. This very specic kind of harmony is called tonal harmony, or functional harmony, and is Europes greatest gift to the Worlds music.. From the perspective of a Western Classical Music historian, the period of Common Practice is now over, but this kind of harmony still provides the back-bone for most of our popular music, and a good deal else. It has also spread to musical cultures which were untouched by it when the period was supposedly ending. Well discuss other non-functional harmonic possibilities later, but for now well look at the kind of harmony we have been surrounded by all our lives . . . . .

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

46 / 85

FUNCTIONAL HARMONY

Two kinds of chord are fundamental to functional / tonal harmony - major & minor chords.

MAJOR & MINOR CHORDS The 1st, 3rd & 5th notes of any major scale constitute its tonic chord. The 1st, 3rd & 5th notes of any minor scale constitute its tonic chord. For example; C, E & G are the 1st, 3rd & 5th notes of a C major scale, so they are a C major chord when played together. C, Eb & G are the 1st, 3rd & 5th notes of a C minor scale, so they are a C minor chord when played together.

(Note that major chords are named without a sufx, but that minor chords need a lower case m). The three notes of every major or minor chord are called the root, third and fth. All major chords incorporate a major third between the root and the third, and a minor third between the third and the fth. All minor chords incorporate a minor third between the root and the third), and a major third between the third and the fth.

(A major third spans 4 semitones, and a minor third spans 3, so you can also calculate the contents of major and minor chords by taking any starting note and then ascending 4 + 3 semitones for a major chord, and 3 + 4 semitones for a minor chord.)

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

47 / 85

DIATONIC CHORDS Every major scale will yield a number of triads (three-note chords). C major, for instance, yields three major chords, three minor chords and one other - a diminished chord (which will be discussed later).

We can extract these chords from the scale without making any chromatic or other alterations and can therefore say that these chords are diatonic in the key of C major. Naming major & minor diatonic chords 1. Jazz & Pop notation Each chord in a key set such as the one above is named after its root. It is assumed that the chord will be a major chord unless you put a lower-case m after it to indicate a minor chord. This system of notation is now very widespread. 2. Roman numerals You can also name chords after the scale steps that they are built on, and, to avoid confusion, Roman Numerals are used. Note that upper-case numerals indicate major chords, and that lower-case numerals indicate minor chords.

3. Functional names The chord built on the tonic is called the tonic chord. Similarly, the chord built on the dominant (fth step) can be called the dominant chord (or simply the dominant), the chord built on the sub-dominant is called the subdominant chord, and so on . . . . . in C major, then, the following chords are named -

System 1 is excellent in playing situations. Systems 2 & 3 have advantages when it comes to analysing and understanding chord sequences.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

48 / 85

MAJOR KEY PRIMARY CHORDS - THE THREE-CHORD TRICK Of the six major & minor chords above, chords I, IV & V are called the Primary Chords. Thousands, possibly millions of tunes and songs are built around these three chords alone and any musician armed with this knowledge can quickly work out an accompaniment to an unfamiliar song hence the Three Chord Trick. This is a pun on Three Card Trick, of course, and this set of chords is indeed a powerful hand - (see what I did there?) - it contains the tonic - the home chord to which all others must lead and on which the piece will come to rest. the dominant - the chord that we feel creates the strongest sensation of a need for the tonic, and the sub-dominant - which creates the same sensation, perhaps not quite so strongly.

SECONDARY CHORDS The three minor chords are known as the Secondary Chords. They are ii, iii & vi, or the supertonic, mediant and sub-mediant. We feel that these lead less directly and powerfully back to the tonic. Notice, however, that the roots of these three chords are related to each other in the same way that the roots of the primary chords are. Here are the primary & secondary chords in C major.

Youll see that the three secondary chords are built on A, D, & E. Taken on their own, these could be I, IV & V - the 3-chord trick - in A minor. This can be very useful, and many chord progressions employ this fact, shifting the emphasis to the Secondary chords and then back to the Primary chords, all to create that satisfying sense of going away from and then back towards the tonic.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

49 / 85

Here are the Primary & Secondary chords in three different major keys -

HIERARCHY OF CHORDS We are beginning to build a picture, I hope, of a hierarchy of chords, some with a more powerful and close relationship to the tonic than others.

THE DOMINANT SEVENTH It is, of course, possible to extract more than 7 chords from a major scale. Some of these may be interesting and beautiful but might not have a clear tonal function (well return to the idea of non-functional harmony later) -

One particular extra chord is, however, very powerful. By adding a seventh to the dominant chord, you create the dominant seventh, and we feel that this chord creates an even greater desire and expectation of the tonic than the simple dominant. In C major, the dominant seventh chord will contain G, B, D & F, the F being 7 steps (specically a minor 7th) above the root of the chord. This would be notated as G7. In any key the dominant seventh chord can be notated as V7, and is often called the 5-7 chord.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

50 / 85

Here, then, is a fuller set of diatonic chords, in a range of keys - notice the dominant sevenths in each key -

MODAL CHORD SETS Although the Major scale came to have enormous importance, there was a time when it was just the Ionian Mode, only one of a set of modes that are actually still in use. Chord sets can be extracted from these modes in exactly the same way that they were extracted from the major scale. For comparison, here are the Ionian (major) and the four other commonest modes (the Dorian, Phrygian, Mixolydian & Aeolian (Natural Minor)), and the chords built on each step -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

51 / 85

The contents of these ve chord-sets are identical, but the chords change their positions and functions in each new mode. In one key, C is the tonic, but it then takes up position as the sub-tonic, sub-mediant, subdominant and nally the mediant. So how and why does C feel like home in one piece, but not in a piece with identical chord-content? How does the chord of Em, a relatively weak chord in C major, then get promoted to the position of dominant in A Aeolian? It is clear that the way in which chords are deployed in actual music is crucial. Chords acquire their status in each new hierarchy partly by being being placed in signicant positions (beginnings and endings of phrases, for instance), and partly by being approached in ways that point up their importance. If the right things arent emphasised at the right times, the chords lose their functionality, progressions lose their dynamic qualities - and the music is less moving. It is also true that, from mode to mode, the relationships between the roots of the chords remain pretty much the same; tonic, dominant and subdominant are still separated by perfect fths, for instance. The new secondary chords might now be found on different steps and might be a mixture of major and minor chords (the Mixolydian) or all major chords (the Aeolian), but they still form sets whose roots are fth-related. These root relationships to some extent override changes and additions to the chord contents. In other words, a D - G - C sequence tends to work whether the individual chords are minor or major because the movement of roots is so clear and powerful. Try these - they all work -

Here are the same modes that you saw above, now transposed to start on the same tonic -

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

52 / 85

Now you can see more easily what these harmonised modes have in common, where they differ, and where they have signicant and unique features. Only the Ionian (the Major), for instance, includes a major dominant, more powerful than the minor dominant because it includes a leading note only a semitone below the tonic. (In some of the other modes, the chord on the subtonic / leading note works almost as well as the dominant when leading back to the tonic). The Phrygian has a unique supertonic chord built on a at 2; this I - II chord relationship immediately identies the music as Flamenco (or perhaps Heavy Metal ). And so on . . . . . .

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

53 / 85

THE CLASSICAL MINOR SYSTEM So far, so simple. The classical minor is more complex. It is more complex than the major and other modes because it includes a number of melodic and harmonic alternatives. If you look back to the section dealing with the Harmonic & Melodic minor scales, youll see that users of these scales have the option of both a major and a minor 6th, and both a major and minor seventh. In the Melodic Minor, the major 6 & 7 are conventionally notated in the ascending version of the scale, and the minor 6 & 7 are written in the descending version -

This is a set of notes that ironically yields far more chords than the so-called Harmonic Minor, and the reality is that, in one style or another, all of them get used. Omitting the three possible diminished chords, we now have a set of 10 chords -

This set includes all six of the chords from the relative major key as well as the chords associated with the natural minor, and a major dominant 7th, of course.

ROCK & POP CHORD SEQUENCES I should mention here that, in a number of rock & pop styles, its common for pieces in major keys to incorporate some of the chords usually associated with the parallel / tonic minor, particularly the major chords built on the at sixth and at seventh steps. A piece in C major, for instance, might well include Ab and Bb chords. There are other ways in which rock practice differs from that so far described, and Ill deal with this later.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

54 / 85

OTHER CHORDS The chord sets described above may be regarded as basic sets; you will certainly use some or all of the chords from each set in a piece, and these will provide the essential framework of your chord progressions. However, you will have noticed that, in practice, chords from outside these sets do get used. First, some chord-types apart from major and minor that can be extracted from the parent scales -

Open \ Power Chords (5) Major or minor chords with the third missing. Much used in folk music and, of course, rock music, particularly Heavy Metal.

Diminished chords ( / dim / m5) You have already seen that each of the scales and modes discussed above contains a diminished chord. A diminished chord may be described as a minor chord with attened fth, or as two superimposed minor thirds.

Note that there is some confusion about the notation of this chord, and the sufx is often used interchangeably with 7 and dim7. This means that there is no way to distinguish between this three-note chord and the four-note 7 as described below. For clarity, it seems worth keeping the notation as described here, then, but be ready for some inconsistency in practice.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

55 / 85

Minor 7th Chords (m7) A minor chord with an added minor 7th. This chord is tonally ambiguous, effectively containing the notes of a minor chord and an overlapping major chord. Note that the sufx m refers to the basic chord. The 7 is assumed to be a minor 7.

Major 7th Chords (maj7 / M7) A Major chord with an added major 7th. Similarly ambiguous. Here the maj or M refers to the seventh - in the absence of a lower-case m, the basic chord is assumed to be a major chord.

Major 6th Chords (6) A major chord with an added 6th. More ambiguity!

Minor 6th chords (m6) A minor chord with an added major sixth.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

56 / 85

9th Chords (9) A major chord with an added minor seventh and a major 9th. (A 9th is effectively the second step of the scale.) Note that the added 7th is assumed here, even though it isnt named.

Major 9th Chords (maj9 /M9) A Major chord with an added major seventh and major 9th. Note that the maj or M refers to the seventh - the fundamental chord and the 9th are assumed to be major.

Suspended 4th Chords ((sus4) / sus4 / sus) A major or minor chord in which the third is replaced by the fourth.

Now a couple of important chords that cant be derived directly from major or minor scales, or any of the modes.

Augmented Chords (+) A major chord with an augmented (sharpened) fth. This can also be thought of as two superimposed major thirds. In effect, a C+ contains the same notes as an E+ and a G#+ so your choice

of name indicates which note you want to be in the bass. Only four distinctly different augmented chords are possible.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

57 / 85

Diminished 7th Chords (7) A minor chord with a diminished fth and an added diminished 7th. You can also think of this as a pile of minor thirds. The silent-movie suspense chord par excellence.

Only four transpositions of this chord are possible so, as with augmented chords, name the chord after the note that you want in the bass. The above are the chords you are most likely to come across, but many others are possible. After the next couple of paragraphs, you will nd a chart summarising the above (including major and minor and dominant seventh chords), and introducing some other chords, too. You might, of course, come across or create chords not in this chart. To name them, follow these rules, some of which have been covered above -

CHORD NAMING RULES

1.

It is assumed that the underlying chord is major unless you say so that a 7th is a minor 7th unless you say so. It follows that an m sufx applies to the fundamental chord, and that maj or M will apply to the 7th.

2.

It is also assumed that If you specify an added 9th, you mean as well as a seventh. If you specify an added 11th (11), you mean as well as a seventh and a ninth. Extend the rule for 13ths etc. 9ths, 11ths, 13ths and 15ths are major unless you say so.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

58 / 85

3.

Other numbers (most likely 6) also imply notes to be added to the fundamental chord.

4.

Sus implies that a chord note is to be replaced. The commonest sus chord is a sus4, where the fourth step replaces the third, so assume this is what is meant if the sufx is simply sus. The only other likely sus chord is a sus 2, and here the third is replaced by the second.

COMMON CHORD TYPES / SUMMARY

Name

Major

Sufx

none

Example

Description

1st, 3rd, & 5th notes of major scale.

Minor

1st, 3rd, & 5th notes of minor scale.

Open / Power Chord

1st & 5th notes of major or minor scale.

Dominant 7th

Major chord with added minor 7th

Major 7th

maj7 / M7

Major chord with added major 7th

Minor 7th

m7

Minor chord with added minor 7th

Minor with major7

mmaj7

Minor chord with added major 7th

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

59 / 85 Sixth 6 Major chord with added major 6th

Minor 6th

m6

Minor chord with added major 6th

Suspended 4th

sus / sus4

Major or minor chord with third replaced by fourth.

Seventh with sus4

7sus4

Dominant 7th chord with 3rd replaced by fourth

Suspended 2nd

sus2

Major or minor chord with third replaced by second.

Added second

2 / add2

Major chord with added second

9th

Major chord with added minor 7th & major 9th

Flat 9th

b9 / 7b9

Dominant 7th chord with added attened 9th. If not using the 7 in the sufx, make sure the at sign is raised - otherwise youre implying a c-at chord. Major chord with added major 7th & major 9th

Major 9th

maj9 / M9

Minor 9th

m9

Minor chord with added minor 7th & major 9th

Diminished

/ dim

Minor chord with attened fth

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

60 / 85 Diminished 7th 7 / dim7 Minor chord with attened fth and added diminished 7th

Augmented

+ / aug

Major chord with sharpened fth

Augmented 7th

+7 / aug7

Augmented chord with added minor 7th

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

61 / 85

CHORD PROGRESSIONS

As hinted at above, the chords and even the chord-families that we have identied are only the building blocks for something far more signicant. This is, of course, the chord progression / chord sequence / harmonic progression, the phenomenon that provided so much of the structure and the forwarddrive for almost all of the European classical music written during the Period of Common Practice, and for the popular song from that period until the present day. An effective chord progression is more than a string of related chords and interesting changes; having established a sense of home and away, it takes the listener on a satisfying, interesting and often emotionally charged journey. It matches and enhances the phrase-by-phrase-structure of a song melody; at the same time, it interacts with melody in ways that enrich its expressive content, and make it more satisfying aesthetically. What follows is a necessarily supercial look at chord sequences, starting with the shortest possible, and then looking at progressively more complex examples, moving from purely diatonic sequences to those that incorporate non-diatonic chords of one kind and another, and then to those that modulate. In passing, well collect some of the tricks of the trade.

TWO CHORD ROCKING SEQUENCES Many pieces have been built on a simple alternation between two chords. One of these chords will inevitably be the tonic chord - the home chord and the other might be almost any other from within the diatonic set. The following example sequences are described in numerals, and followed by a version in the key of C. Try each one as a regularly alternating pattern, and then explore other possibilities . . . . . I - V \ C - G : The most obvious of all chord pairings, the tonic and the dominant. In a major key, no other chord leads so decisively back to the tonic or establishes the tonality so clearly. (My Lady Careys Dompe, 1551 / chorus of Yellow Submarine, 196?) I - IV \ C - F : The next most obvious, but not quite so in your face as the previous pair, perhaps. I - ii \ C - Dm : The classic reggae shift. I - iii \ C - Em : a soft change (only one note difference) but a telling one.

HH2011 \ music theory 1 \ scales \ modes \ intervals \ harmony

62 / 85

I - iii \ C - Am : A similar effect to the last pairing. (Pie Jesu, Faure Requiem / innumerable pop songs) i - bVII \ Cm - Bb : This minor mode shift can be all you need for an Irish jig . . . I - bVII \ C - Bb : And this major version might be all you need for a Scots reel, but it also features in many rock songs, particularly those in the Mixolydian mode. Oh, and The Drunken Sailor.

There are, of course, many other possibilities, particularly when you start to explore minor key and modal chord-sets. From a creative point of view, it may be worth noting that such alternating patterns might be just one section in something grander, and that each twochord relationship has quite distinctive expressive and stylistic implications.