Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

F.SUP - ACLU.JW Memo of P&A PDF

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

F.SUP - ACLU.JW Memo of P&A PDF

Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

2 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 B. C. D. Special Order 7: The LAPDs Response to Impoundment Concerns.............................. 3 The Instant Litigation Challenging Special Order 7 ........................................................ 5 Proposed Intervener Organizations and their Members are Directly Affected by Special Order 7 and the Present Litigation ............................................................................................. 6 A. Car Impounds in California ............................................................................................. 1

9 ARGUMENT.................................................................................................................................. 8 10 I. CHIRLA AND LA VOICE HAVE STANDING AS MEMBERSHIP ORGANIZATIONS TO 11 INTERVENE ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND THEIR MEMBERS...................... 8 12 II. THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT PERMISSIVE INTERVENTION. ................................ 9 13 14 15 16 17 18 D. 19 20 E. The Application is Timely Made. .................................................................................. 15 The Reasons for Intervention Clearly Outweigh Any Opposition. ............................... 15 B. C. A. Proposed Interveners Have a Direct and Immediate Interest in this Action and Can Only Protect It Through Intervention. .................................................................................... 10 Proposed Interveners Interests Cannot Be Adequately Represented by Defendants. .. 12 Intervention Will Not Enlarge the Issues or Otherwise Delay this Case....................... 14

21 CONCLUSION............................................................................................................................. 15 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 i POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 2 3 CASES

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s)

American Horse Protection Assn v. Veneman, 200 F.R.D. 153 (D.D.C. 2001).................................................................................................13 4 5 Bhd. of Teamsters & Auto Truck Divers v. Unemployment Ins., 190 Cal. App. 3d 1515 (1987) ...................................................................................................9 6 Bustop v. Super. Ct., 7 69 Cal. App. 3d 66 (1977) .......................................................................................................10 8 City of Malibu v. Cal. Coastal Commn, 128 Cal. App. 4th 897 (2005) ....................................................................................................8 9 10 Fair Hous. Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommate.com, LLC, 666 F.3d 1216 (9th Cir. 2012) .................................................................................................12 11 Fair Hous. of Marin v. Combs, 12 285 F.3d 899 (9th Cir. 2002) ...................................................................................................12 13 Grutter v. Bollinger, 188 F.3d 394 (6th Cir. 1999) .............................................................................................13, 14 14 15 Lincoln Natl Life Ins. Co. v. Bd. of Equaln, 30 Cal. App. 4th 1411 (1994) ....................................................................................................8 16 Mallick v. Super. Ct., 17 89 Cal. App. 3d 434 (1979) .....................................................................................................15 18 Miranda v. City of Cornelius, 429 F.3d 858 (9th Cir. 2005) .....................................................................................................3 19 20 People ex rel. Rominger v. County of Trinity, 147 Cal. App. 3d 655 (1983) ........................................................................................... passim 21 People v. Williams, 22 145 Cal. App. 4th 756 (2006) ....................................................................................................3 23 Property Owners of Whispering Palms, Inc. v. Newport Pacific, Inc., 132 Cal. App. 4th 666 (2005) ....................................................................................................8 24 25 Royal Indem. Co. v. United Enters., 162 Cal. App. 4th 194 (2008) ..................................................................................................12 26 San Francisco v. State, 27 128 Cal. App. 4th 1030 (2005) ................................................................................................12 28 ii POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 2

Simac Design, Inc. v. Alciati, 92 Cal. App. 3d 146 (1979) .................................................................................................1, 10

Simpson Redwood Co. v. State of Cal., 196 Cal. App. 3d 1192 (1987) .............................................................................................9, 13 3 4 Sturgeon v. City of Los Angeles, No. BC484190 ...........................................................................................................................1 5 Timberidge Enterprises, Inc. v. City of Santa Rosa, 6 86 Cal. App. 3d 873 (1978) .................................................................................................1, 10 7 Trbovich v. United Mine Workers of America, 404 U.S. 528 (1972).................................................................................................................12 8 9 U.S. Ecology, Inc. v. State of California, 92 Cal. App. 4th 113 (2001) ......................................................................................................9 10 United States v. Cervantes, 11 678 F.3d 798 (9th Cir. 2012) .....................................................................................................3 12 Utah Assn of Counties v. Clinton, 255 F.3d 1246 (10th Cir. 2001) ...............................................................................................13 13 14 STATUTES 15 Cal.Veh. Code 12801.5, 14610.7................................................................................................2 16 Cal. Veh. Code 14602.6..................................................................................................2, 4, 5, 12 17 Cal. Veh. Code 22651.....................................................................................................2, 4, 5, 14 18 Code of Civil Procedure 387.....................................................................................................8, 9 19 Code of Civil Procedure 387(a) ..............................................................................................9, 15 20 21 OTHER AUTHORITIES

Attorney General's Final Report 11 (Mar. 2009), available at http://ag.ca.gov/cms_attachments/press/pdfs/n1722_maywoodreport.pdf................................2 22 23 http://articles.latimes.com/2011/feb/28/local/la-me-03-01-bell-baseball-20110301.......................3 24 http://losangeles.cbslocal.com/2012/02/28/police-commission-approves-change-to-lapd-carimpound-policy/.........................................................................................................................4 25 26 Inspector General, Supplemental Review of Biased Policing Complaint Investigations (Dec. 1, 2010) ..........................................................................................................................................3 27 Instant Litigation Challenging Special Order 7 ...............................................................................5 28 iii POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 2

James Burger, Grand Jury Blasts Maricopa Over Impounds, The Bakersfield Californian, June 1, 2011............................................................................................................................................2

Ruben Vives & Jeff Gittlieb, Bell Police Memo Outlines Baseball Game Targeting Drivers, L.A. ............................................................................................................................................3 3 4 Ryan Gabrielson, Sobriety Checkpoints Catch Unlicensed Drivers, N.Y. Times, Feb. 13, 2010...3 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 iv POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 2

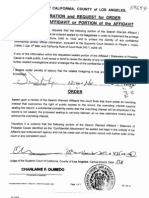

INTRODUCTION This case challenges the Los Angeles Police Departments (LAPDs) Special Order 7 (SO7),

3 a policy on the impoundment of vehicles, which aims to bring LAPDs impoundment practices into 4 compliance with the Fourth Amendment and state law, and to limit the use of punitive 30-day vehicle 5 impoundments to circumstances in which such a harsh measure is warranted. By this motion, LA Voice 6 and the Coalition for Humane Immigrants Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA) two membership 7 organizations that benefit from SO7 seek leave to intervene on behalf of City of Los Angeles (the 8 City), Chief Beck and other defendants (collectively, Defendants), to defend the policy.1 As groups 9 and individuals that benefit directly from SO7, Proposed Interveners have a direct interest in the 10 outcome of these challenges to SO7. Moreover, their interests cannot be adequately represented by the 11 Defendants, who are municipal entities and officials with distinct interests in SO7 and subject to 12 conflicting pressures from different constituencies that may lead them to take positions and advance 13 arguments that differ from the Proposed Interveners. 14 Because the Courts of Appeals have consistently allowed the beneficiaries of a law to intervene

15 in litigation challenging that law, and more than once have found an abuse of discretion where trial 16 courts failed to do so, this Court should grant leave to intervene. See, e.g., People ex rel. Rominger v. 17 County of Trinity, 147 Cal. App. 3d 655 (1983) (holding trial court abused its discretion by denying 18 environmental organization leave to intervene on behalf of its members who were persons protected by 19 challenged ordinance prohibiting use of certain herbicides); Timberidge Enterprises, Inc. v. City of Santa 20 Rosa, 86 Cal. App. 3d 873, 88182 (1978) (holding trial court abused discretion by denying school 21 district leave to intervene in action by developer challenging citys school impact fee); Simac Design, 22 Inc. v. Alciati, 92 Cal. App. 3d 146, 157 (1979) (permitting intervention of association of residents in 23 action by developer against municipality over enforcement of local growth initiative). 24 25 26 27

1

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND A. Car Impounds in California

In 1993, the California Legislature changed the eligibility criteria for a drivers license to require

Proposed interveners have filed identical motions to intervene in both Los Angeles Police Protective Leave v. City of Los Angeles, BC 483052, and Sturgeon v. City of Los Angeles, No. BC484190. 28 1 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 that the applicant provide proof of citizenship or legal residence in the United States. See S.B. 976 2 (1993) (codified in Cal.Veh. Code 12801.5, 14610.7). This change made undocumented residents 3 unable to obtain drivers licenses and made any who drove subject not only to ticketing for driving 4 without a valid license, but also to the impoundment of the vehicles they drove even where the vehicle 5 belonged to a lawfully licensed person other than the driver. When police in California encounter a car 6 being driven by an unlicensed driver, California law gives them the authority (in addition to ticketing the 7 driver) either to store the vehicle until it can be released to a licensed driver (under Cal. Veh. Code 8 22651), on the one hand, or, in certain circumstances, to impound it for a mandatory 30-day period 9 (under Cal. Veh. Code 14602.6), on the other. 10 In the past two decades, vehicle impoundments and in particular mandatory 30-day

11 impoundments have had devastating impacts on working class and immigrant residents who rely on 12 their cars to get to work, take their children to school and do all the other necessary activities for which, 13 in Los Angeles, a car is often essential. Salas Dec. 8; Winkelman Dec. 11; Narro Dec. 8. Worse 14 still, an impoundment in many cases amounts to a de facto forfeiture, as the steep fees associated with a 15 30-day impound (upwards of $2,000) often exceed the amount that a low-income driver can pay, if not 16 the value of the vehicle itself. Salas Dec. 12 ; Winkelman Dec. 12; Narro Dec. 7. Many 17 departments have no policies on when and under what circumstances a 30-day impound should apply, 18 and many officers use a 30-day impound by default whenever they seize the vehicle of unlicensed 19 drivers. Salas Dec. 21. Law enforcement agencies have also been criticized for using impoundments 20 as means of generating revenue, and for targeting Latinos on the assumption that they are more likely to 21 be unlicensed in order to increase impound rates.2 These practices have made impoundments a source 22 See Office of Atty Gen., Cal. Dept of Justice, In the Matter of the Investigation of the City of 23 Maywood Police Department, Attorney General's Final Report 11 (Mar. 2009), available at http://ag.ca.gov/cms_attachments/press/pdfs/n1722_maywoodreport.pdf (finding that impoundment fees 24 appear[] to be the primary motivation for impounding such an extraordinary number of vehicles and 25 that the motive is, at the very least, troublesome, given the serious allegations of corruption that arose during the investigation) (reporting testimony of former Maywood police officer that there were 26 officers who would target, for such stops, individuals who appeared to be undocumented, and one incident in which an officer saw a car being parked by a Latina woman and commented Im going to 27 get her); James Burger, Grand Jury Blasts Maricopa Over Impounds, The Bakersfield Californian, 28 June 1, 2011, http://www.bakersfieldcalifornian.com/politics/local/ x1158262606/Grand-jury-blasts2 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

2

(contd)

1 of tension between police and Latino and immigrant communities. Salas Dec. 10, 11; Narro Dec. 8. 2 In addition, recent federal and state caselaw has held that impoundment under certain

3 circumstances violates the Fourth Amendment. Under the community caretaking doctrine, police can 4 impound without a warrant only vehicles that jeopardize public safety and the efficient movement of 5 vehicular traffic. Miranda v. City of Cornelius, 429 F.3d 858, 864 (9th Cir. 2005) (citation omitted). 6 In Miranda, the Ninth Circuit held that this standard permits impoundment only if it is necessary to 7 remove the vehicle from an exposed or public location and the driver was unable to remove the vehicle 8 lawfully. Id. at 865 (holding impoundment of vehicle lawfully parked in owners driveway unlawful). 9 Courts have applied this rule to hold some impoundments unlawful, including impoundments by LAPD 10 officers prior to SO7. See United States v. Cervantes, 678 F.3d 798, 805-7 (9th Cir. 2012) (holding 11 LAPD impoundment unlawful); People v. Williams, 145 Cal. App. 4th 756, 763 (2006) (holding 12 impoundment unconstitutional where car was legally parked at curb in front of defendants home). 13 14 B. Special Order 7: The LAPDs Response to Impoundment Concerns

LAPD has proved no exception to the statewide concerns over impoundments. In a December

15 2010 analysis of racial profiling complaints, the LAPDs Inspector General noted impounds as an issue 16 and observed some confusion among officers, supervisors, and adjudicators regarding the current 17 Department policy on impounding vehicles of unlicensed drivers. Kaufman Dec., Exh. A (LAPD, 18 Office of the Inspector General, Supplemental Review of Biased Policing Complaint Investigations (Dec. 19 1, 2010)) at 17. The Inspector Generals report recommended further clarification as to the current 20 21 Maricopa-over-impounds (Maricopa police officers have been using aggressive traffic stops and vehicle impounds -- targeting mostly Hispanic drivers -- to bring in revenue to the city under an invalid, 22 exclusive tow contract with Randy's Towing, according to a report released Wednesday by the Kern County Grand Jury.); Ryan Gabrielson, Sobriety Checkpoints Catch Unlicensed Drivers, N.Y. Times, 23 Feb. 13, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/14/ us/14sfcheck.html?pagewanted=all (observing that car impounds for unlicensed driving provide an economic benefit for strapped cities and that the 24 number of impounds have increased significantly in recent years); Ruben Vives & Jeff Gittlieb, Bell 25 Police Memo Outlines Baseball Game Targeting Drivers, L.A. Times, Feb. 28, 2011, http://articles.latimes.com/2011/feb/28/local/la-me-03-01-bell-baseball-20110301 (reporting memo 26 discovered in files of the Bell Police Department appears to outline a game in which police officers would compete to issue tickets, impound cars and arrest motorists and that officers stated that they 27 often spent their shifts pulling over drivers for small infractions in the hope that they would be 28 unlicensed). 3 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 state of the Departments policy regarding the impounding of vehicles of drivers with suspended or 2 expired licenses is merited, including any applicable exceptions to mandatory impounds. Id. at 18. 3 In response to this report and pressure from organizations (including Proposed Interveners),

4 LAPD Chief Charlie Beck proposed a set of procedures governing LAPD officers impoundment of 5 vehicles, entitled Special Order 7. See Kaufman Dec., Exh. B (Special Order 7). Salas Dec. 19; 6 Winkelman Dec. 19. In presenting SO7 to the Police Commission for approval, Chief Beck noted

7 that it addressed the Inspector Generals concerns about officer confusion and helped to clarify various 8 impound protocols to ensure they were consistent citywide, conformed with the application of the 9 Community Caretaking Doctrine, and reflected recent changes in the California Vehicle Code related to 10 vehicle impounds at driving under the influence checkpoints. See Kaufman Dec., Exh. C (Beck Memo 11 to Police Commission). In a hearing on the proposed policy held on February 14, 2012, LAPD Deputy 12 Chief Michel Moore told the Public Safety Committee of the Los Angeles City Council that the revised 13 policy is necessary because officers in the field are often confused about when to impound a car and for 14 how long. According to Deputy Chief Moore, about 85 percent of LAPDs impounds had been issued 15 under a mandatory 30-day hold.3 16 SO7 establishes a tiered approach to guide officers when they encounter a vehicle driven by an

17 unlicensed driver. The policy provides three enforcement options citation with no vehicle seizure, 18 citation and vehicle removal under 22651, and citation and mandatory 30-day impoundment under 19 14602.6 to be utilized depending on certain specified criteria. For individuals found to be driving 20 without a valid California drivers license, officers shall ticket the driver and release a vehicle in lieu of 21 seizure under 22651 or 14602.6 in two circumstances. 4 First, where the registered owner of the 22 vehicle is immediately available and can lawfully drive the vehicle or authorize a licensed driver to 23 drive the vehicle. Second, where the traffic stop is conducted in the registered owner's residential 24 driveway or a legal parking space in the immediate vicinity of the owner's residence, and the registered 25 26 Police Commission Approves Change to LAPD Car Impound Policy, CBS Los Angeles, Feb. 28, 2012, http://losangeles.cbslocal.com/2012/02/28/police-commission-approves-change-to-lapd-car-impound27 policy/. 4 28 All statutory references herein are to the Vehicle Code unless otherwise noted. 4 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

3

1 owner is present on scene. See Exh. B at 2-3. These exceptions are required by the Fourth Amendment 2 under community caretaking principles established by courts. See supra, Section A. 3 If neither of these exceptions is met, and the drivers only offense is driving without a valid

4 license, officers shall ticket the driver and seize the vehicle for storage under 22651 to prevent the 5 immediate and continued unlawful operation as warranted under the Community Caretaking Doctrine. 6 See Exh. B at 3. SO7 provides that officers shall effect a mandatory 30-day impound under 14602.6 in 7 three circumstances: first, where the driver is found driving on a suspended or revoked license, 8 regardless of whether the driver has a prior unlicensed driving violation;5 second, where the driver has 9 never been issued a drivers license (in California or a foreign jurisdiction) and has a prior misdemeanor 10 conviction for driving without a license; third, where the driver has never been issued a drivers license 11 and lacks auto insurance, valid identification, or is at-fault in a collision. See Exh. B at 3. SO7 was 12 approved by the Police Commission and went into effect on April 22, 2012. See Exh. B. 13 14 C. The Instant Litigation Challenging Special Order 7

Plaintiff Los Angeles Police Protective League (PPL) promptly filed an action against the City

15 of Los Angeles charging that SO7 violates the California Vehicle Code and seeking declaratory and 16 injunctive relief restraining and enjoining the City from enforcing SO7. Kaufman Dec., Exh. D (PPL 17 1st Amended Complaint). Shortly after the PPL filed its suit, on May 8, 2012, Plaintiff Harold P. 18 Sturgeon filed a separate action against the City of Los Angeles, raising nearly identical claims and 19 seeking identical relief preventing LAPD from enforcing SO7. See Sturgeon complaint. Kaufman Dec., 20 Exh. E (Sturgeon Complaint). 21 The Court related the two cases on June 21, 2012. Defendants moved to consolidate the actions

22 on June 5, 2012. Defendants filed demurrers to both complaints on July 9, 2012, which this Court has 23 set for hearing on November 9, 2012.6 24 25 26 Officers shall not effect a vehicle seizure if the driver with a suspended or revoked license has no priors and the circumstances fall within the community caretaking exceptions discussed above. 27 6 Proposed Interveners would join the Citys demurrer to both complaints and its arguments regarding 28 the legality of SO7 if they are granted leave to intervene. 5 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

5

1 2 3

D.

Proposed Intervener Organizations and their Members are Directly Affected by Special Order 7 and the Present Litigation

The Coalition for Humane Immigrants Rights Los Angeles (CHIRLA) is a non-profit,

4 membership-based organization focused on organizing and advocacy in Los Angeles on issues of 5 immigrant rights. Id. 3, 4. Some of CHIRLAs members are undocumented and therefore unable to 6 obtain drivers licenses, but are required to drive to get to work, to take their kids (most of whom are 7 United States citizens) to school or to doctors appointments, and to go about daily life in Los Angeles. 8 Id. 8. In recent years, CHIRLAs members have increasingly complained about LAPDs 9 impoundment of their vehicles, or the vehicles that their family uses, when drivers are ticketed for 10 driving without a license. Id. 10. Members report that their vehicle was impounded unnecessarily, 11 when it was lawfully parked or where a family member with a valid drivers license could have safely 12 removed it, and held for 30 days at great expense when the only violation was driving without a license. 13 Id. 9. Many of these individuals have good driving records, and had California drivers licenses prior 14 to 1993 or had licenses in their countries of origin. Id. 8. The expenses associated with 30-day 15 impoundments, which run as high as $2,000, impose significant economic hardship on families, and 16 sometimes force low-income families to go without other necessities like food or medicine. Id. 12. 17 CHIRLAs members also frequently complain that they believe they were stopped by police

18 because they are Latino, and that police unfairly target Latino neighborhoods for traffic enforcement to 19 increase the number of vehicle impoundments. Id. 10. Car impoundments have significantly 20 undermined trust of the LAPD among the immigrant and Latino communities in which CHIRLAs 21 members live, which makes people reluctant to go to the police to identify safety issues and report or 22 provide information on crimes, thus undermining public safety in those communities. Id. 11. 23 As an organization, CHIRLA has itself been impacted by LAPDs car impoundment practices.

24 CHIRLA has been forced to expend significant organizational resources over the past several years 25 assisting its membership in retrieving their impounded vehicles and reporting complaints when LAPD 26 officers impounded cars unlawfully. Id. 22. In addition, members have been forced to give up 27 attending CHIRLAs educational trainings, leadership development and other events because they had a 28 car impounded, hindering CHIRLAs work in other areas. Id. 12, 22. Because of the effects of 6 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 impoundment on its members and its own organizational goals, CHIRLA has led advocacy campaigns at 2 the state and local level, including with the LAPD, for more fair and humane impoundment policies. Id. 3 16-17, 19-20. If SO7 is enjoined, CHIRLAs members will again suffer the hardships from 4 impounds they endured before the policy was enacted, and CHIRLA will be forced to divert resources 5 away from its civic engagement, community education and leadership development initiatives towards 6 impound assistance. 7 Id. 23.

LA Voice is the Los Angeles affiliate of People Improving Communities through Organizing

8 (PICO), a national network in 150 cities and 18 states including more than one thousand religious 9 congregations, schools, and neighborhood organizations. Winkelman Dec. 8. LA Voice is an 10 interfaith, community organization comprised of more than 20 membership congregations of diverse 11 faiths devoted to conducting leadership development and advocacy training to empower local 12 communities to transform their neighborhoods and to improve the quality of life of Los Angeles 13 residents. Id. 4, 6. At least seven of LA Voices membership congregations consist primarily of 14 immigrant families, a considerable number of which have members who do not have legal immigration 15 status and as a result are unable to obtain a California drivers license. Id. 9, 10. 16 In recent years, LA Voice membership congregations have identified impounds as a critical issue

17 because they cause severe hardships for the families in LA Voice. Id. 12. Many congregants are 18 undocumented and have had a car impounded for 30 days after being cited for driving without a license, 19 including people who have clean driving records and had been licensed in California prior to 1993 or in 20 a foreign jurisdiction. Id. 10, 11. Because so many of these individuals have no choice but to rely on 21 a car to get to work, they are forced to pay impound fees which can result in them having to forgo other 22 necessities like food, medical care and congregational tithes. Id. 12. LAPDs impoundment practices 23 have created significantly higher levels of distrust between the police and the Latino and immigrant 24 communities in which these congregations are based. Id. 13. 25 Car impoundments have also directly affected LA Voices ability to carry out its mission and

26 programs. LA Voice is funded by dues-paying membership congregations, as well as individual 27 donations. Id. 6. For congregations in immigrant neighborhoods, the financial burdens of car 28 impounds have reduced the ability of many congregants to donate to their congregations, and in turn to 7 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 LA Voice. Id. 15. Moreover, impounds have also impeded directly on LA Voices empowerment and 2 education programs because participants without drivers licenses often do not attend LA Voice 3 meetings and actions for fear they may be stopped by the police and lose their vehicles. Id. 4 Because impounds affect both the families of LA Voice and the effectiveness of the

5 organization, LA Voice for the past several years has made LAPDs impound policy a focus of its 6 advocacy, by organizing community members, conducting public demonstrations and meeting 7 frequently with leaders in the LAPD and city government. Id. 16, 17. SO7 promises to save the 8 families of LA Voice thousands of dollars in unnecessary fines and the prolonged loss of vehicles on 9 which many of their livelihoods depend. Id. 22. If SO7 is held unlawful, LA Voices membership 10 congregations will continue to face the financial burdens of exorbitant car impoundment fees, reducing 11 donations to LA Voice and impeding its ability provide services and trainings to its membership 12 congregations. Id. 23. Further, staff hours will have to be allocated to continuing advocacy efforts 13 that will limit the organizations ability to conduct other campaigns and programming. Id. 14 15 ARGUMENT Code of Civil Procedure 387 allows nonparties to intervene in an action, thereby becoming

16 parties to the litigation. The purpose of intervention is to promote fairness by allowing all parties 17 who may be affected by the outcome of litigation to participate. Lincoln Natl Life Ins. Co. v. Bd. of 18 Equaln, 30 Cal. App. 4th 1411, 1423 (1994) (intervention proper where party has an interest and 19 intervention neither expands scope of litigation nor infringes upon original parties right to litigate case). 20 For that reason, courts must liberally construe the statute in favor of intervention. See City of Malibu v. 21 Cal. Coastal Commn, 128 Cal. App. 4th 897, 902 (2005); Lincoln Natl, 30 Cal. App. 4th at 1423. 22 I. 23 24 CHIRLA AND LA VOICE HAVE STANDING AS MEMBERSHIP ORGANIZATIONS TO INTERVENE ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND THEIR MEMBERS. [A]n association has standing to bring suit on behalf of its members when: (a) its members

25 would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; (b) the interests it seeks to protect are germane 26 to the organization's purpose; and (c) neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires the 27 participation of individual members in the lawsuit. Property Owners of Whispering Palms, Inc. v. 28 Newport Pacific, Inc., 132 Cal. App. 4th 666, 673 (2005). As set forth below, members of both 8 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 CHIRLA and LA Voice have interests that would grant them standing to intervene in their own right. 2 The issue is germane to the purpose of CHIRLA and LA Voice, which educate and organize immigrant 3 communities around issues that affect them and have worked on impoundment in other contexts. 4 Neither resolution of the legal issues surrounding SO7 nor the requested relief that the LAPDs policy be 5 upheld involve any particularized circumstances of the members of LA Voice or CHIRLA, and so do 6 not require their individual participation in the litigation. See Bhd. of Teamsters & Auto Truck Divers v. 7 Unemployment Ins., 190 Cal. App. 3d 1515, 1523 (1987). 8 II. 9 THIS COURT SHOULD GRANT PERMISSIVE INTERVENTION. Californias standard for permissive intervention is extremely broad and liberally construed in

10 favor of intervention. Code of Civil Procedure 387(a) provides in pertinent part, Upon timely 11 application, any person, who has interest in the matter in litigation, or in the success of either of the 12 parties, or an interest against both, may intervene in the action or proceeding. While permitting 13 intervention under section 387(a) is a matter of the courts discretion, U.S. Ecology, Inc. v. State of 14 California, 92 Cal. App. 4th 113, 139 (2001) (citations omitted), it is well-established that Section 387 15 should be liberally construed in favor of intervention. Simpson Redwood, 196 Cal. App. 3d at 1200 16 (reversing trial court order refusing permissive intervention). 17 A third party may intervene in an action if (1) the party has a direct and immediate interest in

18 the action; (2) the intervention will not enlarge the issues in the litigation; and (3) the reasons for 19 intervention outweigh any opposition by the parties presently in the action. U.S. Ecology, 92 Cal. App. 20 4th at 139. As set forth in detail below, all three prongs of this inquiry weigh in favor of allowing 21 intervention here. Proposed interveners have a direct and immediate interest in a determination of the 22 legality of SO7, a policy under which Proposed Interveners membership will benefit and that will 23 permit Proposed Interveners to dedicate organizational resources to their educational programs, trainings 24 and other initiatives rather than assisting their members with car impounds. Proposed Interveners 25 participation in these lawsuits will not enlarge the issues in the litigation. Finally, Proposed Interveners 26 interests cannot be adequately represented by the Defendants, which include municipal entities and their 27 officers who are subject to conflicting pressures from different constituencies, particularly in litigation 28 that pits the City of Los Angeles against one of its largest employee unions, the PPL. 9 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 2 3

A.

Proposed Interveners Have a Direct and Immediate Interest in this Action and Can Only Protect It Through Intervention.

To show a direct and immediate interest in this litigation, interveners need not have any

4 pecuniary interest in the dispute, or a specific legal or equitable interest in the subject matter of the 5 litigation. Rominger, 147 Cal. App. 3d at 661; see also Bustop v. Super. Ct., 69 Cal. App. 3d 66, 70-71 6 (1977) (holding that parents opposed to school busing had sufficient interest in a sound educational 7 system and in the operation of that system in accordance with the law to permit intervention in an 8 action concerning school districts desegregation plan.). The purposes of [permissive] intervention are 9 to protect the interests of those who may be affected by the judgment. Timberidge, 86 Cal. App. 3d at 10 881 (emphasis in original, quotation omitted). To be permitted to intervene, it is not necessary that his 11 interest in the action be such that he will inevitably be affected by the judgment. It is enough that there 12 be a substantial probability that his interests will be so affected. Id. (emphasis in original). 13 Applying these standards, courts have routinely granted the intended beneficiaries of a local

14 policy leave to intervene in an action challenging that policy, and appellate courts have held trial courts 15 abused their discretion by failing to allow intervention in such circumstance. See Rominger, 147 Cal. 16 App. 3d at 665 (holding trial court abused its discretion by denying environmental organization leave to 17 intervene on behalf of its members who were persons protected by challenged ordinance restricting use 18 of certain herbicides and pesticides); Timberidge Enterprises, 86 Cal. App. 3d at 881-82 (reversing trial 19 court decision denying school district leave to intervene in action by developer challenging citys school 20 impact fee); Simac Design, 92 Cal. App. 3d at 157 (permitting intervention of association of citizens 21 who campaigned for local growth initiative, in action against municipality challenging enforcement of 22 that initiative). As the Court of Appeal reasoned in Rominger, Where a [policy] exists specifically to 23 protect the public from a hazard to its health and welfare that would allegedly occur without such 24 [policy], members of the public have a substantial interest in the protection and benefit provided by such 25 [policy]. If a party brings an action to invalidate such [policy] such action has an immediate and direct 26 effect on the publics interest in protecting its health and welfare. 147 Cal. App. 3d at 662-63.7 27 In Rominger, the state challenged county ordinances controlling the use of herbicides claiming that state law preempted the ordinances, the court held that the Sierra Clubs interests in the litigation were 28 (contd) 10 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

7

Under the reasoning of these decisions, Proposed Interveners clearly have a direct and

2 immediate interest in this challenge to SO7. The membership of CHIRLA and LA Voice, as 3 individuals whose vehicles (or the vehicles of family members) are likely to be subject to impoundment, 4 are clearly the intended beneficiaries SO7s limitation on the use of the punitive 30-day impound and 5 guidance on avoiding impoundments that violate the Fourth Amendment and the California Vehicle 6 Code. Without the policy in place, the membership of Proposed Interveners will be subjected to the 7 substantially more burdensome 30-day impounds and thus will suffer an interference with their 8 property interest in their vehicles that has serious consequences for their ability to earn a living, get 9 education for their children, engage in political activity, and go about their daily lives. Even those 10 members of CHIRLA and LA Voice who themselves never drive without a license have an interest in 11 ensuring that the vehicles they rely on are not subject to prolonged forfeiture should a family member be 12 stopped for driving without a license. 13 Further, without SO7, Proposed Interveners members face a greater likelihood that the LAPD

14 will continue its traffic enforcement and vehicle impoundment practices that routinely resulted in the 15 violations of members constitutional and statutory rights. For example, CHIRLAs members report 16 that, prior to SO7, LAPD officers towed members vehicles in absence of any community caretaking 17 reasons. Salas Dec. 9. In addition, LAPD officers routinely impounded for 30-days vehicles driven by 18 CHIRLA and LA Voice members who had been licensed in California prior to 1993 or in a foreign 19 jurisdiction, despite the fact that the Vehicle Code does not authorize 30-day impoundments in such 20 21 sufficiently direct and immediate to justify permissive intervention. The Sierra Club alleged that its members would be harmed if spraying . . . resumes in Trinity County in the absence of the 22 ordinances Rominger, 147 Cal. App. 3d at 662. The court found that in making this allegation, the Sierra Club not only alleged specific harm, but place[d] itself among the persons that the ordinances 23 were specifically designed to benefit and protect. Id. Accordingly, the court concluded that the Sierra Club, as representative of its members who reside in and use the resources of Trinity County, has a 24 direct and immediate, rather than consequential and remote, interest in this litigation. Id. at 663. The 25 court concluded that the Sierra Clubs interest was sufficiently direct and immediate because, [i]n the absence of the instant ordinance, it is highly likely that the use of phenoxy herbicides in Trinity County 26 would resume. Id. So, too, in this case, it is highly likely that police use of the 30-day impoundment of vehicles will resume in the absence of SO7, given the wide use of the 30-day impoundment before the 27 policy went into effect and plaintiffs arguments that SO7 is invalid because the 30-day impoundment 28 period is mandatory. 11 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 circumstances. Salas Dec. 8; Winkelman Dec. 10. SO7 now expressly recognizes this limitation on 2 14602.6. 3 CHIRLA and LA Voice, as organizations, also have an interest in preserving the more moderate

4 impound policies of SO7. When fewer cars are impounded from their members, CHIRLA and LA 5 Voice will not have their resources diverted from educational trainings and leadership development 6 initiatives to assisting members with the consequences of impoundments, nor will their membership 7 continue to be subject to extreme financial burdens from car impounds that limit their ability to 8 contribute to the organizations. This clearly constitutes a direct and immediate interest in the validity of 9 SO7. See, e.g., Fair Hous. of Marin v. Combs, 285 F.3d 899, 905 (9th Cir. 2002) (organization has 10 direct standing to sue [when] it show[s] a drain on its resources from both a diversion of its resources 11 and frustration of its mission); Fair Hous. Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommate.com, LLC, 12 666 F.3d 1216, 1219 (9th Cir. 2012) (finding standing for organization that had diverted resources to 13 new education and outreach campaigns targeted at discriminatory roommate advertising).8 14 Indeed, precisely because both CHIRLA and LA Voice, and their members, have a direct interest

15 in limitations on impoundments, both organizations spent significant resources getting LAPD to put SO7 16 in place. Salas Dec. 19; Winkelman Dec. 16; Narro Dec. 10. This is not a mere political interest, 17 but an indication of the substantial stake Proposed Interveners have in the subject of this litigation. 18 19 B. Proposed Interveners Interests Cannot Be Adequately Represented by Defendants.

The Proposed Interveners interests cannot be adequately represented by the Defendants. While

20 the Proposed Interveners defenses and claims may well align with the Defendants, there are critical 21 differences and significant potential for divergence of interests. See Trbovich v. United Mine Workers of 22 America, 404 U.S. 528, 538 n.10 (1972) (holding that an applicant need only show that representation 23 of his interest may be inadequate). 24 The Proposed Interveners have a personal stake in the litigation and can, therefore, speak directly

25 to the benefits that they gain from SO7. The Proposed Interveners have a unique interest in ensuring the 26 While intervention under the federal rules is more lenient, San Francisco v. State, 128 Cal. App. 4th 27 1030, 1043 (2005), federal case law in this area is instructive, even when we utilize California criteria 28 for permissive intervention. Royal Indem. Co. v. United Enters., 162 Cal. App. 4th 194, 204 (2008). 12 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

8

1 preservation of SO7 to avoid harm to their members and to ensure that their organizational resources are 2 not diverted to assisting membership with impound issues. 3 Neither the City nor officials named as defendants here have any such personal interest. The

4 Defendants interest in the matter lies principally in protecting the legality of their own actions. Such a 5 governmental interest is not coincident with the personal stake of affected persons and organizations, 6 and it therefore does not justify denying intervention to Proposed Interveners. See, e.g., Rominger, 147 7 Cal. App. 3d at 665 (a county that acted on behalf of its residents to defend pesticide ordinances could 8 not represent the personal interests of Sierra Club members in supporting those ordinances); Simpson 9 Redwood Co. v. State of Cal., 196 Cal. App. 3d 1192, 1203-04 (1987) (reversing trial courts refusal to 10 allow intervention in part on the conviction that appellants own substantial interests probably cannot 11 be adequately served by the State's sole participation).9 12 As a governmental entity, moreover, the City is subject to conflicting and shifting constituent

13 pressures, which renders its representation of the Proposed Interveners particular interests inadequate. 14 See Utah Assn of Counties v. Clinton, 255 F.3d 1246, 1254-55 (10th Cir. 2001) (holding interveners 15 interest not adequately represented by government entity that must represent the broader public interest, 16 which it may not view as coextensive with the interveners particular interest); Grutter v. Bollinger, 188 17 F.3d 394, 400 (6th Cir. 1999) (noting, in granting intervention, that the University of Michigan is 18 subject to internal and external institutional pressures that may prevent it from articulating some of the 19 defenses of [the race-conscious policies] that the proposed interveners intend to present); American 20 Horse Protection Assn v. Veneman, 200 F.R.D. 153, 159 (D.D.C. 2001) (holding that, while the United 21 States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the intervener show horse fund shared identical interests 22 in asserting that the Operating Plan [preventing soring of horses] is lawful, the USDAs obligations to 23 interests other than those represented by the [intervener] render its representation of the show horse 24 25 26 27 28

9

For example, here, LAPD has stated that SO7 was adopted in part to ensure the Departments compliance with Fourth Amendment limitations on when law enforcement can seize vehicles without a warrant under the Community Caretaking doctrine. It is possible that Defendants may seek only to defend SO7 on this basis, and decline to defend provisions of SO7 that cannot be justified on those grounds. Such litigation tactics would not represent Proposed Interveners, who have an interest in, and will vigorously defend, SO7 in its entirety to protect the benefits that the policy provides to the Proposed Intervener organizations and their membership. 13 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

1 groups inadequate). Here, such concerns are heightened because these lawsuits pit the City against one 2 of its largest employee unions, the PPL. The PPL and Defendant City have a collective bargaining 3 relationship that touches on numerous issues with no connection to the subject matter of these lawsuits, 4 and that ongoing relationship undoubtedly places Defendants under certain institutional pressures that 5 may lead them to take positions based on considerations apart from the merits of these cases. In 6 balancing the potentially competing interests of their various constituencies, Defendants may wish to 7 settle the case and agree not to enforce SO7, or might decline to appeal or seek Supreme Court review of 8 an adverse decision. Such action would in no way represent the interests of the Proposed Interveners, 9 who want to prevent harm to undocumented immigrants and their families, ensure community trust with 10 the LAPD, and promote access to social and legal services and work opportunities. 11 Further, Defendants may not raise important considerations that led to the formation of SO7 and

12 support its legality for fear that they paint LAPD in a bad light, including but not limited to, information 13 regarding LAPDs prior inconsistent impound practices and complaints regarding racial profiling by 14 LAPD officers in traffic enforcement. In this regard, the Proposed Interveners arguments will differ 15 from those of Defendants precisely because their interests are different. See Grutter, 188 F.3d at 400 16 (noting, in granting intervention, that the University of Michigan may not articulat[e] some of the 17 defenses of [the race-conscious policies] that the proposed interveners intend to present). These 18 considerations are relevant here, where the PPL seeks to enjoin a policy which it claims will violate state 19 law even though its members were doing precisely what SO7 provides seizing cars pursuant to 20 22651 on an ad hoc and inconsistent basis prior to the adoption of SO7. Proposed Interveners are 21 uniquely positioned to provide the Court with this information, as the Proposed Interveners 22 organizations and their membership have firsthand experience with the LAPDs impoundment practices 23 and the harms they created. 24 25 C. Intervention Will Not Enlarge the Issues or Otherwise Delay this Case.

While the Proposed Interveners seek to join this suit to protect their individual and organizational

26 rights and interests in the potential outcome of the suit, the legal defenses and issues asserted by 27 Proposed Interveners are similar to those already asserted in the litigation and based on the same facts. 28 Nor do Proposed Interveners seek to delay any proceedings or alter deadlines in the case. Intervention 14 POINTS & AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO INTERVENE

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Chris Gill DOJ ComplaintDocument34 pagesChris Gill DOJ ComplaintPoliceabuse.com100% (1)

- La11cv04846 Sjo JDocument3 pagesLa11cv04846 Sjo JAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Search Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesDocument47 pagesSearch Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesBetsy A. RossPas encore d'évaluation

- Zoot Suit Riots EssayDocument7 pagesZoot Suit Riots Essayapi-356870623Pas encore d'évaluation

- ACLU SoCal Annual Report 2013Document17 pagesACLU SoCal Annual Report 2013American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Advocate TrainingDocument127 pagesCommunity Advocate TrainingAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kern County Courthouse Letter To ICEDocument6 pagesKern County Courthouse Letter To ICEAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Stipulation and Settlement AgreementDocument6 pagesStipulation and Settlement AgreementAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Court Stops UCLA Move Against VetsDocument13 pagesCourt Stops UCLA Move Against VetsGordon DuffPas encore d'évaluation

- Attorneys For Respondents and Defendants: Reply To Opposition To Demurrer (BS 142775)Document19 pagesAttorneys For Respondents and Defendants: Reply To Opposition To Demurrer (BS 142775)American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- How It Works: Local Control Funding FormulaDocument2 pagesHow It Works: Local Control Funding FormulaAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2833 001Document1 page2833 001American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Settlement: Moreno v. City of AnaheimDocument16 pagesSettlement: Moreno v. City of AnaheimAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern California100% (1)

- Kern County Courthouse Letter To ICEDocument6 pagesKern County Courthouse Letter To ICEAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- LCAPDocument1 pageLCAPAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- CDE SBE Guidance LetterDocument4 pagesCDE SBE Guidance LetterAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- LGBTQ KYR - Updated June 2013Document2 pagesLGBTQ KYR - Updated June 2013American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Williams v. California: Nine Years LaterDocument64 pagesWilliams v. California: Nine Years LaterAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- La11vcv04846 Sjo MoDocument21 pagesLa11vcv04846 Sjo MoAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- CARRP Press ReleaseDocument3 pagesCARRP Press ReleaseAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- ACLU Comes To Oxy 4setp13Document2 pagesACLU Comes To Oxy 4setp13American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Report From ACLU On Discrimination Against Muslims and People of The Middle East.Document76 pagesReport From ACLU On Discrimination Against Muslims and People of The Middle East.Shah Peerally100% (1)

- Trust Act Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesTrust Act Press ReleaseAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Valentini - Opposition To MSJDocument23 pagesValentini - Opposition To MSJAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- FINAL Hesperia Letter To ACLU SoCal Press Release 8 15 2013Document2 pagesFINAL Hesperia Letter To ACLU SoCal Press Release 8 15 2013American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Valentini V Shinseki: Pls MSJDocument29 pagesValentini V Shinseki: Pls MSJAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Valentini V Shinseki Govt MSJ BriefDocument33 pagesValentini V Shinseki Govt MSJ BriefAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 - 06-21 (0129) Plaintiffs' Reply in Support of Motion For Summary JudgmentDocument7 pages2013 - 06-21 (0129) Plaintiffs' Reply in Support of Motion For Summary JudgmentAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- First Amended ComplaintDocument30 pagesFirst Amended ComplaintAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Valentini V Shinseki Pls OppDocument26 pagesValentini V Shinseki Pls OppAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Valentini - Defs. MSJ ReplyDocument7 pagesValentini - Defs. MSJ ReplyAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- LTR To Inland Empire SchoolsDocument8 pagesLTR To Inland Empire SchoolsAmerican Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hesperia Responds To ACLU 08-07-13Document4 pagesHesperia Responds To ACLU 08-07-13American Civil Liberties Union of Southern CaliforniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Michael ConnellyDocument419 pagesMichael ConnellySateesh MaduukuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Loyola Police and Community SurveyDocument25 pagesLoyola Police and Community SurveyDaily KosPas encore d'évaluation

- Valley Cultural Center Concert On The Green Program 2010Document84 pagesValley Cultural Center Concert On The Green Program 2010valleyculturalcenterPas encore d'évaluation

- Data-Informed Community-Focused Policing: in The Los Angeles Police DepartmentDocument27 pagesData-Informed Community-Focused Policing: in The Los Angeles Police DepartmentJake LancePas encore d'évaluation

- LAPDDocument55 pagesLAPDjetlee estacionPas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD Homicide Case File ProfileDocument41 pagesLAPD Homicide Case File ProfileMarj BaquialPas encore d'évaluation

- Ruiz Lawsuit Against The LAPDDocument11 pagesRuiz Lawsuit Against The LAPDDennis RomeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Back To Basic Car White PaperDocument10 pagesBack To Basic Car White PaperCouncilDistrict11100% (3)

- Justice Facilities ReviewDocument94 pagesJustice Facilities ReviewMihaela PopaPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument37 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRockie Geronda Esmane58% (12)

- LAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Spring 2010Document12 pagesLAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Spring 2010Los Angeles Police Reserve FoundationPas encore d'évaluation

- Los Angeles Police Body Camera ReportDocument22 pagesLos Angeles Police Body Camera ReportGuns.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Lapd Reserve Officers Honored: Banquet at Reagan Presidential Library, Appreciation Day BBQ Held at PabDocument12 pagesLapd Reserve Officers Honored: Banquet at Reagan Presidential Library, Appreciation Day BBQ Held at PabLos Angeles Police Reserve FoundationPas encore d'évaluation

- West LA College - ScheduleDocument93 pagesWest LA College - ScheduleDushtu_HuloPas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Summer 2015Document20 pagesLAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Summer 2015Los Angeles Police Reserve FoundationPas encore d'évaluation

- The Beat - LAPD Chief of Police NewsletterDocument16 pagesThe Beat - LAPD Chief of Police NewsletterAlan MeekerPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodney Rouzan Final ComplaintDocument14 pagesRodney Rouzan Final ComplaintknownpersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Race War v2 - Wake 2019Document32 pagesRace War v2 - Wake 2019ConnorPas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD ChartDocument1 pageLAPD ChartPramboediePas encore d'évaluation

- Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Bul-1347-2 MinaDocument30 pagesChild Abuse and Neglect Reporting Bul-1347-2 MinamillikanartsPas encore d'évaluation

- Declaration of Kelley Lynch 06.30.14Document64 pagesDeclaration of Kelley Lynch 06.30.14Odzer ChenmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mayor Garcetti Submits Scientology $20K DonationDocument6 pagesMayor Garcetti Submits Scientology $20K DonationTony OrtegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Campus Safety Plan 2018 - 2Document9 pagesCampus Safety Plan 2018 - 2Ana Maria IordachePas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD Officer Charges W Human SmugglingDocument4 pagesLAPD Officer Charges W Human Smugglingildefonso ortizPas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Summer 2013Document12 pagesLAPD Reserve Rotator Newsletter Summer 2013Los Angeles Police Reserve FoundationPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis Essay Final Draft RevisedDocument6 pagesAnalysis Essay Final Draft Revisedapi-340272184Pas encore d'évaluation

- LAPD Statement On Venice Officer-Involved ShootingDocument2 pagesLAPD Statement On Venice Officer-Involved ShootingMike BoninPas encore d'évaluation