Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Fifth

Transféré par

Vũ TrangDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Fifth

Transféré par

Vũ TrangDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

ADULT BASIC EDUCATION

Volume 6, Number 2, Summer 1996, 105-111

BOOK REVIEW ________________________________________________________________________ Peter M. Senge (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday Currency. One of the concepts that Peter Senge relies on in The Fifth Discipline is mental models. Mental models are important, argues Senge, because they set the way we From this view, what we observe is not reality itself as an objective

perceive reality.

quality out there, but our perception of reality which is invariably shaped by our world view. Moreover, on Senges reading, organizational perception in particular is socially

constructed which, he believes, provides untold opportunity for renewal if constructed in an appropriate systems-like fashion. Thus, in improving relationships among people in

organization, Senge recommends a combination of critical inquiry, discussion (by which he means advocacy) and dialogue. A sensitive implementation of these

processes will foster greater learning and will help to diminish the endemic learning disabilities which he feels are pervasive within our organizations. Such activity

combined with incisive systems analysis generated through stewardship leadership which unleashes and channels the free flowing of multiple perspectives may greatly expand the knowledge base that is not possible to stimulate within organizations simply through individual thinking, however creative and brilliant. Through such perspective

transformations (Mezirow, 1990), the mental model for an organization may change dramatically for the better on Senges reading. The Fifth Discipline, widely touted as one of the most important books in the field, is part of a growing genre of organizational development literature that focuses on the theme of continuous improvement through the unleashing of a socially constructed, self-realization ethos as the propelling engine of institutional life. Thus, many of the

topics that Senge highlights; personal mastery, mental models, shared vision and team

learning (chapters 9-11) are pervasive in the literature. There is little exciting or new in those chapters although they provide an adequate summary of thinking on the various topics and for that reason alone, are useful. Senges particular slant on these topics is the importance of systems thinking which he views as indispensable for the specific qualities that reinforce an ethos of continuous improvement to have maximum impact in fostering long term institutional change. He views the various components, then, of his ideal organization as grounded dominant progressive

systemically as part of a holographic reality where Each represents the whole image from a different point of view (p. 212). Through organic integration advocates who

can also inquire into others visions, open the possibility for the vision to evolve, to become larger than our individual visions. That is the principle of the hologram (p.

228), and I believe, the apogean vision beneath Senges emphasis on systems thinking. A systems perspective allows one to look beneath the surface of events to the underlying structures of behavior and attitudes in order to gain leverage for constructive change not accessible through a concentration on specific events. Thus, Senge

encourages the reader to consider archetypes through which structural dilemmas are identified at their root which in turn can beckon an appropriate, although often painful response by organizational members. The belief in archetypes as the real sources of

organizational life is central to Senges thesis, yet they remain underdeveloped in his argument even as they are implicit throughout the book. In chapter 6 (pp. 93-113), Senge does spell out two archetypes in some depth, which is helpful. The first, the one I will deal with, is Limits to Growth, which he

defines as the following: A reinforcing (amplifying) process is set in motion to produce a desired result. It creates a spiral of success but also creates inadvertent secondary effects...which eventually slow down the success (p. 95).

Senges management principle is Dont push growth; remove the factors limiting growth. Senge explains this in part by drawing on a pervasive goal in our culture; The push factor is to eat less and less food, which may

reaching our desired weight.

result in initial success. Yet, as most of us who have tried to maintain permanent weight loss know, excessive dieting more often than not boomerangs so that we regain most or all of our initial weight loss. On Senges account, leverage is gained by raising ones

metabolic rate through exercise and then, in turn, developing a positive attitude about food which then, ideally, eradicates or greatly reduces the compulsion to overeat and the equally addictive excessive dieting syndrome. Senge points to, but does not fully grapple with a fundamental dilemma with the Limits to Growth archetype. He states that growth to some extent will always be

stymied by various limiting factors and in some situations, growth will eventually stop. Under such conditions: Efforts to extend the growth by removing limits can counterproductive, forestalling the day of eventual reckoning (p. 103). actually be

In the dieting example the continuous limiting forces, in addition to biology, are the profound contradictions within the culture of the United States that promote an ethic of self-realization, including the quest for the perfect body on the one hand against a powerful consumer based ideal upon which the economy depends, on the other hand. This, in turn, broadcasts the message that we can eat (a metaphor for general consumption) all that we desire as an expression of our self-realization. With these

contradictory messages, it is little wonder that this nation has such a vast health problem (physical and mental) with obesity on the one hand and excessive dieting and exercise regimes on the other hand. I will not go into it here. Yet I encourage the reader to draw on Senges dieting example to evaluate the challenges and dilemmas of growth in organizational life mediated through the complex interaction of a wide range of internal

and external forces broadly related to the relationship between productivity (output) and consumption (profits). It is unfortunate that Senge did not explore the more fundamental structural, economic and social limitations to organizational growth, although it is understandable why he did not, since to do so could very well have vitiated his praxeological goals. Still, it is through such realities that the proponents of continuous improvement must make their case if their objective of establishing the new corporate culture on an ethos of enlightened humanism is to hold muster. The proponents of such literature (Steven R.

Covey, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, and Tom Peters and Robert H. Waterman in the popularly acclaimed In Search of Excellence) offer a profusion of strategies and insights that can ameliorate some of the oppressive stagnancy and hierarchy which characterize so many organizations which induce conformity, compliance and resignation among so many employees. Since reality is porous and

subject to on-going change, the insights that this literature provide can be appropriated at the top, at the middle or at the bottom of a hierarchy with the likelihood of effecting some change that can enhance human freedom, efficacy and creativity within organizations. Yet, one of the problems of this literature, and Senge is particularly susceptible, is that it over promises by offering the prospect of evolution, and ignoring the constraining realities and limiting conditions out of which the vast majority of organizations actually operate. For example, Senge maintains that Today, the discipline

of team learning is, I believe, poised for a breakthrough because we are gradually learning how to practice (p. 259). Hopefully, the literature may teach us some useful things about team learning. Yet in my experience, I see nothing that points to a

breakthrough, with the concomitant implication that if we finally learn the appropriate means of team learning in conjunction with the other disciplines, we will undergo fundamental change in our organizational life. Hopefully, we will experience some

improvement, although any trajectory toward a teleology of continuous improvement,

remains at least in my mind, rather suspect. Perhaps a few organizations will experience dramatic cultural shifts that point toward a new ethos of collaboration, stewardship, service, excellence, and self-realization to which the literature points. It is important to

keep open to the possibility that organizations could make moves in such directions, most likely in a piece-meal way at best, lest we artificially restrict reality by negative selffulfilling prophecies. Yet, if history and contemporary experience offer any guide to the future, it is exceedingly unlikely that the kind of dramatic breakthroughs envisioned (the grand organizational cosmology) would actually come to pass. At least on a scale large enough to significantly effect the social life or workplace of the vast majority of people who are still required to make meaning even in the highly ambiguous work settings of a precarious post-industrial economy. Senge is not unaware of this dilemma, since for his holographic theory to work, an organization needs to embrace his entire systems package, an extremely rare occurrence, particularly in large-scale, complex institutions. His observation about one

type of industry is indicative of much of contemporary organizational life, particularly given the current reality (1996) of massive downsizing, mergers and restructuring in the declining post-industrial economy of the north east. His observation is that most of our services dont serve very well (p. 332). It is this more pervasive reality than the relatively few organizations that even begin to emulate the values proposed in The Fifth Discipline that needs to be factored in when a ssessing the viability of Senges model as a viable engine of reform for this nations economic institutions. Elsewhere, he argues that one of the major functions of top leadership is the designing of the organizations learning processes (p. 300) so that its culture may proximate the vision of creative community for which he advocates. Yet, the e nduring reality of this societys current and historical practice points in another direction as Senge, himself acknowledges: The fact that few of those presently in such positions recognize this role is one of the main reasons that learning organizations are still rare.

Thus, in contrast to the confusing and ambiguous experience of so much of lived reality (contemporary and historical), Senge offers the prospect of continuous improvement through right (systems) thinking. In his scenario collective thinking is

always more valuable and "correct" than individual thought, although in Senges vision, individuality is enhanced through a proper alignment with an integrated, self-actualized organization. As he states it: This does not imply that we must sacrifice our vision for the larger cause. Rather, we must allow multiple visions to coexist, listening for the right course of action that transcends and unifies all our individual visions (p. 218). I do not argue that on rare occasions such a compelling sense of unity may not arise in particular local settings or that the quest for a broadening of our own personal visions is not valuable. When such opportunities do arise, we should do everything we can to

nurture and develop them. What I do question is the likelihood of this happening to any significant degree n i the vast majority of organizations that dominate contemporary life and the reasons for such failure are much more complex than the inability to engage in right thinking. Rather, constraints, conflicts, and various pathological cultural assumptions that are inherent within the broader socio-cultural, politico-economic environment are

internalized within our institutions which can not be easily dislodged.

In a word,

organizations are inextricably political entities that in many ways reflect the distribution of power and the dominant cultural assumptions of the wider society. Thus, the concept of stewardship that Senge proposes (pp. 342-352) buts up against the profit motive as the underlying value and rational of the private enterprise system. This problem of power and conflicting agendas is pervasive within the non-profit sector as well. Literacy and

adult education programs, for example, have played an important role in enabling many individuals who lacked opportunities earlier to enhance their lives through the attainment of formal education in later years. There is no gainsaying the importance of this for the

particular individuals effected.

Yet, such a benefit is far from problematical.

As

Reihnold Niebuhr, one of the most important political theologians of the mid-twentieth century put it about African-American schools in the earlier years of this century, which transfers quite easily to mainline adult literacy institutions: They operate within a given system of injustice. The Negro schools, conducted under the auspices of white philanthropy, encourage individual Negroes to higher forms of self-realization; but they do not make a frontal attack upon the social injustices from which the Negro suffers (Cited in Rasmussen, 1991, p. 66). This is not to imply bad intentions nor to impinge upon the motivation of adult literacy volunteers and program directors who often work diligently under hard pressed circumstances. Yet it is meant to help recognize the constraints and limits as well as the possibilities and opportunities available to those who labor in this field. Thus, it is not an insignificant issue whether the essentially underfunded, understaffed literacy and adult basic education programs significantly ameliorate or mask the more enduring problems associated with adult illiteracy. To have force, Senges structural interpretation would

have to extend well beyond the intricate workings of organizational life and confront the socio-cultural forces that reinforce racism, inequality, poverty, and sexism which are pervasive within our institutions as well as in our broader social, cultural, and political life. I raise these issues not to dismiss Senges observations and suggestions, many of which are quite astute. Yet, there is a need to take a hard look at the philosophical

premises of The Fifth Discipline and through that, the broader humanistic organizational literature to which it belongs in light of the contemporary socio-economic context. If

history and contemporary practice is any guide to the near term future, our major institutions will not likely be structurally transformed in ways that would enable Senges vision to flourish in modern organziational life. This leaves us with a dilemma. On the one hand, we can embrace Senges vision unreservedly. We allow

ourselves to be persuaded by the force of his rhetorical argument that we in fact can

fashion

our

institutions

toward

the

path

of

continuous

improvement through

enlightened systems thinking.

If so, we may be operating under the illusion that the

future may allow us to fulfill utopian possibilities that at best are only partially present in our contemporary setting. His argument, to state it baldly, is that the future can become On the other hand, if we

fundamentally more life-giving than current reality.

categorically reject Senges vision as unrealizable in any of its significant dimensions, we risk the possibility of defining the present as an unalterable force to which we are fated to obey. On such a structural-functional scenario, we cut asunder the potency of free will to alter unsatisfying conditions to any degree: Eventually this will breed deep cynicism about...visions in general. The soil within which a vision must take root-the belief that we can influence our futurebecomes poisoned (p. 355). Part of the difficulty I have with Senge is that his vision is too all-encompassing. It really doesnt work unless all the component parts are integrated and buttressed by a systems perspective. Senge is fully aware that he does not resolve the many dilemmas to which he points (p. 272), but his hope that they can be transcended through more effective systems learning, I find troubling. I dont believe that we are required to embrace the cynicism of despair in order to be realistic. Reality is not so constrained that historical actors lack power to effect

organizational life, although my sense is that such influences are likely to be considerably more piecemeal and ambiguous than desired by the proponents of continuous evolution. Occasionally, significant new breakthroughs may take place in our

institutional life which may serve as prototypes or models for new behavior in specific industries or services. My sense, though, is that even within such experimental settings,

much of traditional behavior will color the organizational culture and that the new and the old will exist in ambivalent, but hopefully creative tension. In this societys dominant

institutions, traditional patterns of behavior will, in all likelihood, maintain even a

stronger hold, although there may be room for reformist energies to establish regions of influence that variably effect the life of an organization. There is room, therefore, for

growth," but not without the carrying of a great deal of baggage that we might perhaps rather see removed. The self-realization and collaborative themes articulated in the humanistic organizational literature are valuable, but particularly so when a sense of limits is built into the process of implementing desired changes. Books such as The Fifth Discipline are worth reading. Yet only with the reader fully engaged in a dialogue with the text,

listening to, but not willing to succumb to the rhetorical force of particular arguments; instead, arguing back forcefully, at times, especially when personal experience moves in a counter direction. REFERENCES Bennis, W. (1989). On becoming a leader. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. Covey, S. R. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Restoring thecCharacter ethic. New York: Simon & Schuster. Covey, S.R. (1990). Principle-centered leadership. New York: Simon & Schuster. Kanter, R.M. (1983). The change masters: Innovation and entrepreneurship in the American corporation. New York: Simon & Schuster. Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.Z. (1990). The leadership challenge: extraordinary things done in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Mezirow, J. and Associates (1990). Francisco: Jossey-Bass. How to get

Fostering critical reflection in adulthood. San

Peters, T. and Waterman, H. Jr. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America's best run companies. New York: Warner Books. Rasmussen, L., ed. (1991). Reinhold Niebuhr: Theologian of public life. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

10

George Demetrion Manager of Community-Based Programming Literacy Volunteers of Greater Hartford Gdemetrion@juno.com

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Internal Conflict of EnterpriseDocument3 pagesThe Internal Conflict of Enterpriseav.kumar85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies of God: A Biblical Blueprint for Personal and Organizational EffectivenessD'EverandStrategies of God: A Biblical Blueprint for Personal and Organizational EffectivenessPas encore d'évaluation

- Lewin's Theory For ChangeDocument17 pagesLewin's Theory For ChangeBill Whitwell100% (1)

- Psychological AdjustmentDocument100 pagesPsychological AdjustmentRagil Adist Surya PutraPas encore d'évaluation

- Finding the Missing Pieces: How to Solve the Puzzle of Digital Modernization and TransformationD'EverandFinding the Missing Pieces: How to Solve the Puzzle of Digital Modernization and TransformationPas encore d'évaluation

- 4984 Dainton Chapter 3Document24 pages4984 Dainton Chapter 3Catalin Balint-CodreanPas encore d'évaluation

- Creating A Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesCreating A Learning OrganizationZahraJanellePas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Organization - PETER SENGEDocument23 pagesLearning Organization - PETER SENGEBy GonePas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Senge and The Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesPeter Senge and The Learning OrganizationMarc RomeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Positive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorDocument15 pagesPositive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorGlobal Research and Development ServicesPas encore d'évaluation

- OD PractitionersDocument5 pagesOD Practitionerssofronio v aguila jr100% (2)

- Week 3 - Reading - Reinventing - Management - Extract1 PDFDocument7 pagesWeek 3 - Reading - Reinventing - Management - Extract1 PDFLavinia DinuPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter M.docxFifth Dicipline OutlineDocument6 pagesPeter M.docxFifth Dicipline OutlineMarietta FernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- ID 261 Mjoen K, Lyso IDocument9 pagesID 261 Mjoen K, Lyso IMoh SaadPas encore d'évaluation

- Empowerment Theory, Research, and Application: Douglas D. PerkinsDocument14 pagesEmpowerment Theory, Research, and Application: Douglas D. PerkinsmbabluPas encore d'évaluation

- Sarahbeth Gareis Ogl 340 Final 20211008Document7 pagesSarahbeth Gareis Ogl 340 Final 20211008api-594507221Pas encore d'évaluation

- Traditional Definition of Organization DevelopmentDocument3 pagesTraditional Definition of Organization Developmentmachevallie100% (1)

- Moral Mazes - Bureaucracy and Managerial WorkDocument17 pagesMoral Mazes - Bureaucracy and Managerial WorkLidia GeorgianaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Eyes Within Book Excerpt April 2010Document8 pagesThe Eyes Within Book Excerpt April 2010Dawna JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Besley Ghatak EvolutionofMotivationDocument40 pagesBesley Ghatak EvolutionofMotivationEne GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Behavior Over Time GraphsDocument8 pagesBehavior Over Time Graphsmanisha_bhavsarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice: ReviewsDocument4 pagesThe Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice: ReviewsveriaryantoPas encore d'évaluation

- 24 Leaders Paradox SimpleDocument11 pages24 Leaders Paradox Simplealostguy1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership in Living Organizations - SengeDocument11 pagesLeadership in Living Organizations - SengeamongeaglePas encore d'évaluation

- Reframed - A Journal of Self-Reg - Volume 1, Issue 1Document117 pagesReframed - A Journal of Self-Reg - Volume 1, Issue 1Sarah BehlPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovation Change Management Articles tcm36-68774Document20 pagesInnovation Change Management Articles tcm36-68774eliasPas encore d'évaluation

- Action Research in Rip?: EditorialDocument3 pagesAction Research in Rip?: EditorialDeepthiPas encore d'évaluation

- AssignmentDocument2 pagesAssignmentMirza Raqeem AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- An Overview of OT by SulemanDocument4 pagesAn Overview of OT by SulemanOscar PinillosPas encore d'évaluation

- GROSS - Universities As OrganizationsDocument28 pagesGROSS - Universities As OrganizationsMaria Caramez CarlottoPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership in Living Organizations - Peter SengeDocument11 pagesLeadership in Living Organizations - Peter Sengeapi-242746630Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Essay 2 - 8.3Document7 pagesSample Essay 2 - 8.3david legematePas encore d'évaluation

- Dijagnoza Kroz Ciklus Konatakta II GrupaDocument43 pagesDijagnoza Kroz Ciklus Konatakta II Grupabojana413Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 3, HU102-WA0006.9Document7 pagesModule 3, HU102-WA0006.9kanishka.kspPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Understanding Whole System ChangeDocument26 pages1 Understanding Whole System Changeintj2001712Pas encore d'évaluation

- The 5th DisciplineDocument9 pagesThe 5th DisciplineSuman Poudel100% (2)

- Changing Facets of ODDocument9 pagesChanging Facets of ODpriyanka0809Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Fifth DisciplineDocument15 pagesThe Fifth DisciplineZau Seng50% (2)

- Presence Work BookDocument41 pagesPresence Work BookchoileoPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Resource Theory From Hawthorne Experiments of Mayo To Groupthink of JanisDocument21 pagesHuman Resource Theory From Hawthorne Experiments of Mayo To Groupthink of JanisfarisyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 10 - Web Materials George Kelly and Personal Construct PsychologyDocument10 pagesChapter 10 - Web Materials George Kelly and Personal Construct Psychologymakcin_cyril3142Pas encore d'évaluation

- Creating We - Chaning I Thinking To WE PDFDocument10 pagesCreating We - Chaning I Thinking To WE PDFmandarem100% (1)

- General Psychology Dedicated To Positive Psychology, Where The EditorsDocument4 pagesGeneral Psychology Dedicated To Positive Psychology, Where The EditorsJ0SUJ0SUPas encore d'évaluation

- 01growth Development2Document67 pages01growth Development2ikeokwu clintonPas encore d'évaluation

- Development EconomicsDocument24 pagesDevelopment EconomicsLester Jao SegubanPas encore d'évaluation

- Circular "Questioning" in Organizations: Discovering The Patterns That Connect Bella Borwick, D.L. PsychDocument11 pagesCircular "Questioning" in Organizations: Discovering The Patterns That Connect Bella Borwick, D.L. PsychWangshosanPas encore d'évaluation

- Appreciative Inquiry: Accentuating The Positive: BestpracticeDocument4 pagesAppreciative Inquiry: Accentuating The Positive: BestpracticePooja AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Change and Development Chapter 12Document27 pagesOrganizational Change and Development Chapter 12Basavaraj PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Senge and The Learning OrganizationDocument11 pagesPeter Senge and The Learning OrganizationEna Fazlic100% (1)

- Kurt Lewin's Change Theory in The Field and in The Classroom: Notes Toward A Model of Managed LearningDocument21 pagesKurt Lewin's Change Theory in The Field and in The Classroom: Notes Toward A Model of Managed Learninghoracio simunovic díazPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept 10.1-Organisational Chagne As A Cultural ProcessDocument4 pagesConcept 10.1-Organisational Chagne As A Cultural ProcessadhilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational Theory NotesDocument253 pagesOrganizational Theory NotesFausta BukontaitėPas encore d'évaluation

- The Future of Educational Change: System Thinkers in ActionDocument10 pagesThe Future of Educational Change: System Thinkers in ActionDaniela VilcaPas encore d'évaluation

- Organization: Applied Behavioral ScienceDocument3 pagesOrganization: Applied Behavioral ScienceTnumPas encore d'évaluation

- Motivation Is The Driving Force Which Help Causes Us To Achieve Goals. Motivation Is Said To BeDocument7 pagesMotivation Is The Driving Force Which Help Causes Us To Achieve Goals. Motivation Is Said To Beravikant456Pas encore d'évaluation

- Building Strategy From The Middle: Reconceptualizing Strategy ProcessDocument18 pagesBuilding Strategy From The Middle: Reconceptualizing Strategy ProcessItaliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Collective Action and The Group Size Paradox: Joan EstebanDocument31 pagesCollective Action and The Group Size Paradox: Joan EstebanTyas safhiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Training in Difficult Choices: 5 Public Policy Case Studies From SlovakiaDocument101 pagesTraining in Difficult Choices: 5 Public Policy Case Studies From Slovakiascholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Education in Medieval Bristol and GloucestershireDocument20 pagesEducation in Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershirescholar786100% (1)

- Classical Islamic Educa Vrs US EduDocument14 pagesClassical Islamic Educa Vrs US Eduscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- MethodologyPoliticalTheory PDFDocument28 pagesMethodologyPoliticalTheory PDFscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- The First Musannaf of Ibn Abi ShaybahDocument552 pagesThe First Musannaf of Ibn Abi Shaybahscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Historical Development of Muslim MutazilismDocument4 pagesHistorical Development of Muslim Mutazilismscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Can Creativity Be LearnedDocument4 pagesCan Creativity Be Learnedscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Phenomenological Case Study of A Principal Leadership - The InflDocument292 pagesA Phenomenological Case Study of A Principal Leadership - The Inflscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lughaat Al Quran G A ParwezDocument736 pagesLughaat Al Quran G A Parwezscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Al Farabi TranslationDocument271 pagesAl Farabi Translationscholar786100% (1)

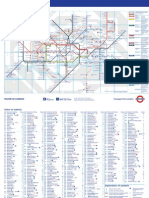

- Standard Tube MapDocument2 pagesStandard Tube Mapscholar786Pas encore d'évaluation

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobD'EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (37)

- How to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersD'EverandHow to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (95)

- Summary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendD'EverandSummary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsD'EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (57)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverD'EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (186)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleD'EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2566)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0D'EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelD'EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceD'EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (22)

- Summary: Choose Your Enemies Wisely: Business Planning for the Audacious Few: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisD'EverandSummary: Choose Your Enemies Wisely: Business Planning for the Audacious Few: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsD'EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (52)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelD'EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Good to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tD'EverandGood to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (63)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionD'EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (337)

- The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthD'EverandThe Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (35)

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessD'EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (132)

- Unlocking Potential: 7 Coaching Skills That Transform Individuals, Teams, & OrganizationsD'EverandUnlocking Potential: 7 Coaching Skills That Transform Individuals, Teams, & OrganizationsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (28)

- Leadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsD'EverandLeadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (11)

- The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsD'EverandThe 4 Disciplines of Execution: Revised and Updated: Achieving Your Wildly Important GoalsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (48)

- The Manager's Path: A Guide for Tech Leaders Navigating Growth and ChangeD'EverandThe Manager's Path: A Guide for Tech Leaders Navigating Growth and ChangeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (99)

- The Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things HarderD'EverandThe Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things HarderPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthD'Everand7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (52)

- Multipliers, Revised and Updated: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone SmarterD'EverandMultipliers, Revised and Updated: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone SmarterÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (146)

- The Little Big Things: 163 Ways to Pursue ExcellenceD'EverandThe Little Big Things: 163 Ways to Pursue ExcellencePas encore d'évaluation

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsD'EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (411)

- The E-Myth Revisited: Why Most Small Businesses Don't Work andD'EverandThe E-Myth Revisited: Why Most Small Businesses Don't Work andÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (709)