Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hobsbawm 1996

Transféré par

gugamachalaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hobsbawm 1996

Transféré par

gugamachalaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

HOBSBAWM, Eric J. The age of extremes: a history of the world, 1914-1991. New York: Vintage, 1996. 627p.

The history of the twenty years after 1973 is that of a world which lost its bearings and slid into instability and crisis. p. 403. Nobody seriously doubted that for these parts of the world [terceiro mundo] the 1980s were an era of severe depression. p. 405. Between 1990 and 1993 few attempts were made to deny that even the developed capitalist world was in depression. p. 408. Nevertheless, the central fact about the Crisis Decades is not that capitalism no longer worked as well as it had done in the Golden Age, but that its operations had become uncontrollable. Nobody knew what to do about the vagaries of the world economy or possessed instruments to manage them. p. 408 The crisis decades were the era when the national state lost its economic powers. p. 408. The only alternative offered was that propagated by the minority of ultra-liberal economic theologians. Even before the crash, the long-isolated minority of believers in the unrestricted free market had begun their attack on the domination of the Keynesians and other champions of the managed mixed economy and full employment. p. 409. Champions of absolute individual freedom were unmoved by the evident social injustices of unrestricted market capitalism, even when (as in Brazil for most of the 1980s) it did not produce economic growth. p. 410. However, the model [Swedish Model] was also, and perhaps even more fundamentally, undermined by the globalization of the economy after 1970, which put the governments of all states except perhaps the U.S.A., with its enormous economy at the mercy of an uncontrollable world market. p. 411. There were good grounds for some of the disillusion with state-managed industries and public administration that became so common in the 1980s. p. 412. In any case most neo-liberal governments were obliged to manage and steer their economies, while claiming that they were only encouraging market forces. p. 412. The historic tragedy of the Crisis Decades was that production now visibly shed human beings faster than the market economy generated new jobs for them. p. 414. The massive entry of the U.S.S.R. on the international grain market, and the impact of the oil crises of the 1970s dramatized the ending of the socialist camp as a virtually self-contained regional economy protected from the vagaries of the world economy. p. 418.

Only one generalization was fairly safe: since 1970 almost all the countries in this region [third world] had plunged deeply into debt. p. 422. There was a moment of genuine panic in the early 1980s when, starting with Mexico, the major Latin American debtors could no longer pay, and the Western banking system was on the verge of collapse, since several of the largest banks had lent their money with such abandon in the 1970s (when petro-dollars flooded in, clamouring for investment) that they would now be technically bankrupt. p. 423. The main effect of the Crisis Decades was thus to widen the gap between rich and poor countries. p. 424. During the heyday of the free-market theologians, the state was further undermined by the tendency to dismantle activities hitherto conducted by public bodies on principle, leaving them to the market. p. 425. The triumph of neo-liberal theology in the 1980s was, in effect, translated into policies of systematic privatization and free-market capitalism which were imposed on governments too bankrupt to resist them, whether they were immediately relevant to their economic problems or not [] p. 431. The other apparently fortunate consequences of the oil crises was the flood of dollars which now spurted from multi-billionaire OPEC states, often with tiny populations, and which was distributed by the international banking system in the form of loans to anyone who wanted to borrow. Few developing countries resisted the temptation to take millions thus shoveled into their pockets, and which were to provoke the world debt crisis of the early 1980s. p. 474 What drove the Soviet Union with accelerating speed towards the precipice, was the combination of glasnost that amounted to the disintegration of authority, with a perestroika that amounted to the destruction of the old mechanisms that made the economy work, without providing any alternative; and consequently the increasingly dramatic collapse of the citizens standard of living. p. 483. The attempt to save the old structure of the Soviet Union had destroyed it more suddenly and irrevocably than anyone had expected. p. 495. Thus, for the first time in two centuries, the world of the 1990s entirely lacked any international system or structure. p. 559 It was therefore likely that the fashion for economic liberalization and marketization, which had dominated the 1980s, and reached a peak of ideological complacency after the collapse of the Soviet system, would not last long. p. 574. The immediate reaction of Western commentators to the collapse of the Soviet system was that it ratified the permanent triumph of both capitalism and liberal democracy, two concepts which the less sophisticated of North American world-watchers tended to confuse. p. 575.

Increasingly, however, governments took to by-passing both the electorate and its representative assemblies, if possible, or at least to taking decisions first and then challenging both to reverse a fait accompli, relying on the volatility, divisions or inertness off public opinion. p. 580.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The End of Protest: How Free-Market Capitalism Learned to Control DissentD'EverandThe End of Protest: How Free-Market Capitalism Learned to Control DissentPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary Of "USA, World War I To 1930s Crisis" By Elena Scirica: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESD'EverandSummary Of "USA, World War I To 1930s Crisis" By Elena Scirica: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESPas encore d'évaluation

- What if Latin America Ruled the World?: How the South Will Take the North Through the 21st CenturyD'EverandWhat if Latin America Ruled the World?: How the South Will Take the North Through the 21st CenturyPas encore d'évaluation

- Capitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryD'EverandCapitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (9)

- Summary Of "Some Reflections On Globalization And Neoliberalism In Latin America And Argentina" By Patricia Romer Hernández: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESD'EverandSummary Of "Some Reflections On Globalization And Neoliberalism In Latin America And Argentina" By Patricia Romer Hernández: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESPas encore d'évaluation

- Empire of Chaos EditableDocument116 pagesEmpire of Chaos EditableQaiser KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- WHY ARE THEY SO POOR?: CAPITALISM: A PEOPLE'S HISTORYD'EverandWHY ARE THEY SO POOR?: CAPITALISM: A PEOPLE'S HISTORYPas encore d'évaluation

- Shifting Sands: Assessing What Ended and What Did Not in the 2008 Financial CrisisDocument23 pagesShifting Sands: Assessing What Ended and What Did Not in the 2008 Financial Crisiscowley75Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Balance Sheet of Sovietism PDFDocument296 pagesThe Balance Sheet of Sovietism PDFDon_HardonPas encore d'évaluation

- People Before Profit: The New Globalization in an Age of Terror, Big Money, and Economic CrisisD'EverandPeople Before Profit: The New Globalization in an Age of Terror, Big Money, and Economic CrisisÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (6)

- The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960sD'EverandThe Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960sÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Keys of This Blood: Pope John Paul II Versus Russia and the West for Control of the New World OrderD'EverandKeys of This Blood: Pope John Paul II Versus Russia and the West for Control of the New World OrderÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (23)

- Economics in Perspective: A Critical HistoryD'EverandEconomics in Perspective: A Critical HistoryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (9)

- The End of "End of HistoryDocument17 pagesThe End of "End of HistoryEsteban ZapataPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of Central Banking and the Enslavement of MankindD'EverandA History of Central Banking and the Enslavement of MankindÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (11)

- What New World OrderDocument15 pagesWhat New World OrdernailawePas encore d'évaluation

- America - The Covenant Nation - A Christian Perspective - Volume 2: From the Rise of the Dictators in the 1930s to the PresentD'EverandAmerica - The Covenant Nation - A Christian Perspective - Volume 2: From the Rise of the Dictators in the 1930s to the PresentPas encore d'évaluation

- The Commanding Heights: Battle for World EconomyDocument7 pagesThe Commanding Heights: Battle for World EconomyEdwin GilPas encore d'évaluation

- The New World Crisis: Origins of the Second Cold War and World War IIID'EverandThe New World Crisis: Origins of the Second Cold War and World War IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- East-West Trade Trends: Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (the Battle Act) ; Fourth Report to Congress, Second Half of 1953D'EverandEast-West Trade Trends: Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (the Battle Act) ; Fourth Report to Congress, Second Half of 1953Pas encore d'évaluation

- Summary Of "Mexico: A People In History" By Elsa Gracida & Esperanza Fujigaki: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESD'EverandSummary Of "Mexico: A People In History" By Elsa Gracida & Esperanza Fujigaki: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESPas encore d'évaluation

- New Left Review 61 Jan-Feb 2010Document217 pagesNew Left Review 61 Jan-Feb 2010negressePas encore d'évaluation

- The Impending Crisis: Conditions Resulting from the Concentration of Wealth in the United StatesD'EverandThe Impending Crisis: Conditions Resulting from the Concentration of Wealth in the United StatesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Downfall of Money: Germany’s Hyperinflation and the Destruction of the Middle ClassD'EverandThe Downfall of Money: Germany’s Hyperinflation and the Destruction of the Middle ClassÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- The Breakdown of Capitalism & The Fight For Socialism in The United StatesDocument20 pagesThe Breakdown of Capitalism & The Fight For Socialism in The United Statesurdrighten2Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Long Gilded Age: American Capitalism and the Lessons of a New World OrderD'EverandThe Long Gilded Age: American Capitalism and the Lessons of a New World OrderÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- Panitch and Gindin - Capitalist Crises and The Crisis This TimeDocument20 pagesPanitch and Gindin - Capitalist Crises and The Crisis This TimeYasin_Kaya_1877Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Mexican Heartland: How Communities Shaped Capitalism, a Nation, and World History, 1500–2000D'EverandThe Mexican Heartland: How Communities Shaped Capitalism, a Nation, and World History, 1500–2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- 6 BaruchelloLintner Final DraftDocument21 pages6 BaruchelloLintner Final DraftTo-boter One-boterPas encore d'évaluation

- Latin American Democracy After The Lost "Half Decade" (1997-2002) - How To Rescue Political Science From The "Third Wave of Democratization"?Document18 pagesLatin American Democracy After The Lost "Half Decade" (1997-2002) - How To Rescue Political Science From The "Third Wave of Democratization"?Gonzalo CaminoaPas encore d'évaluation

- FRIENDS As FOES by Immanuel WallersteinDocument7 pagesFRIENDS As FOES by Immanuel WallersteinEsteban MarinPas encore d'évaluation

- East-West Trade Trends: Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (the Battle Act)D'EverandEast-West Trade Trends: Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (the Battle Act)Pas encore d'évaluation

- One Mistake, One Hundred Million Deaths: The Two Biggest Ideas of the 20th CenturyD'EverandOne Mistake, One Hundred Million Deaths: The Two Biggest Ideas of the 20th CenturyPas encore d'évaluation

- Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the WorldD'EverandCapitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the WorldÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (7)

- Revolution in Development: Mexico and the Governance of the Global EconomyD'EverandRevolution in Development: Mexico and the Governance of the Global EconomyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Crisis of Socialist Modernity: The Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the 1970sD'EverandThe Crisis of Socialist Modernity: The Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the 1970sPas encore d'évaluation

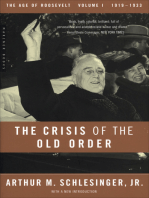

- The Crisis of the Old Order 1919–1933: The Age of Roosevelt, 1919–1933D'EverandThe Crisis of the Old Order 1919–1933: The Age of Roosevelt, 1919–1933Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Revenge of History: The Battle for the 21st CenturyD'EverandThe Revenge of History: The Battle for the 21st CenturyÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)

- Uk Fin Warfare-LeninDocument93 pagesUk Fin Warfare-LeninsylodhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Alain Lipietz Mirages and Miracles Crisis in Global FordismDocument235 pagesAlain Lipietz Mirages and Miracles Crisis in Global FordismBlackrtuy100% (1)

- B10a: Martingales Through Measure Theory: Alison EtheridgeDocument52 pagesB10a: Martingales Through Measure Theory: Alison EtheridgegugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Regional EvolutionsDocument75 pagesRegional EvolutionsgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Macroeconomic PrioritiesDocument14 pagesMacroeconomic PrioritiesgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ma WH in Analyse CompletDocument814 pagesMa WH in Analyse CompletgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Communist ManifestoDocument34 pagesThe Communist ManifestogugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ggplot (Data ) + (Mapping Aes )Document1 pageGgplot (Data ) + (Mapping Aes )gugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tecnicas de Filmagem PDFDocument70 pagesTecnicas de Filmagem PDFgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Macroeconomic PrioritiesDocument14 pagesMacroeconomic PrioritiesgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Econophysics PDFDocument4 pagesEconophysics PDFgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Regional EvolutionsDocument75 pagesRegional EvolutionsgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Transformation CheatsheetDocument2 pagesData Transformation CheatsheetNitish KansariPas encore d'évaluation

- EngDocument60 pagesEngwidhisaputrawijayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Beginners Guide World of WatercolorDocument27 pagesBeginners Guide World of WatercolorGesana Biti88% (8)

- Regras DC DSBDocument35 pagesRegras DC DSBgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gustavo Machala: Auto-Determination of Nations - A Principle That Must Be FollowedDocument1 pageGustavo Machala: Auto-Determination of Nations - A Principle That Must Be FollowedgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ggplot2 Cheatsheet 2.1Document2 pagesGgplot2 Cheatsheet 2.1berker_yurtsevenPas encore d'évaluation

- United States - Anti-Dumping Act of 1916Document45 pagesUnited States - Anti-Dumping Act of 1916gugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- United States - Anti-Dumping Act of 1916Document45 pagesUnited States - Anti-Dumping Act of 1916gugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Not Ate Me GuideDocument35 pagesNot Ate Me GuideDsamparoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14Document42 pagesGilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14gugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- John Mearsheimer's Offensive Realism TheoryDocument28 pagesJohn Mearsheimer's Offensive Realism TheoryAlex MinuiPas encore d'évaluation

- World Trade Report 2006 eDocument266 pagesWorld Trade Report 2006 eBogdan BelenchePas encore d'évaluation

- Export Credit Agencies and The WtoDocument11 pagesExport Credit Agencies and The WtogugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Courant DifferentialIntegralCalculusVolIiDocument695 pagesCourant DifferentialIntegralCalculusVolIiAlda England100% (5)

- Gilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14Document42 pagesGilens and Page 2014-Testing Theories 3-7-14gugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- World Trade Report 2006 eDocument266 pagesWorld Trade Report 2006 eBogdan BelenchePas encore d'évaluation

- Export Credit Arrangement OCDE PDFDocument33 pagesExport Credit Arrangement OCDE PDFgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Price Behavior Under Antidumping LawDocument30 pagesPrice Behavior Under Antidumping LawgugamachalaPas encore d'évaluation

- World Trade Report 2006 eDocument266 pagesWorld Trade Report 2006 eBogdan BelenchePas encore d'évaluation

- On National Culture - Wretched of The EarthDocument27 pagesOn National Culture - Wretched of The Earthvavaarchana0Pas encore d'évaluation

- 96.1 (January-February 2016) : p23.: Military ReviewDocument7 pages96.1 (January-February 2016) : p23.: Military ReviewMihalcea ViorelPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignement 3 - 25 Mediserv v. CADocument3 pagesAssignement 3 - 25 Mediserv v. CApatrickPas encore d'évaluation

- European Refugee and Migrant Crisis Dimensional AnalysisDocument23 pagesEuropean Refugee and Migrant Crisis Dimensional AnalysisTanmay VermaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reorganizing Barangay Peace Order CommitteeDocument3 pagesReorganizing Barangay Peace Order CommitteeHaa Lim DimacanganPas encore d'évaluation

- CTA erred in dismissing tax case due to non-payment of docket feesDocument3 pagesCTA erred in dismissing tax case due to non-payment of docket feesJeffrey MagadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eo #8. Badac Auxilliary TeamDocument2 pagesEo #8. Badac Auxilliary Teamronnel untalanPas encore d'évaluation

- My Name Is Rachel Corrie PDFDocument23 pagesMy Name Is Rachel Corrie PDFIvania Cox33% (3)

- Jurisdiction of CourtsDocument6 pagesJurisdiction of CourtsMjay GuintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Arbitration Law ReviewerDocument4 pagesArbitration Law ReviewerKathrine TingPas encore d'évaluation

- Leg Ethics DigestDocument1 pageLeg Ethics DigestsamanthaPas encore d'évaluation

- Yeo v. Town of Lexington, 1st Cir. (1997)Document134 pagesYeo v. Town of Lexington, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Parliamentary Democracy President Knesset 12 Standing Committees Elections GovernmentDocument3 pagesParliamentary Democracy President Knesset 12 Standing Committees Elections GovernmentNico ParksPas encore d'évaluation

- Aversive Racism - (Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 36) Mark P. Zanna-Elsevier, Academic Press (2004)Document449 pagesAversive Racism - (Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 36) Mark P. Zanna-Elsevier, Academic Press (2004)Victor de Sales AlexandrePas encore d'évaluation

- LABOUR LAW Mumbai UniversityDocument98 pagesLABOUR LAW Mumbai Universityhandevishal444Pas encore d'évaluation

- CourtRuleFile - 3987DD3D CRPC Sec 125Document9 pagesCourtRuleFile - 3987DD3D CRPC Sec 125surendra kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Ec-Thailand Country Strategy PaperDocument65 pagesThe Ec-Thailand Country Strategy PaperOon KooPas encore d'évaluation

- ZANZIBAR TELECOM COMPANY Vs HAIDARI RASHIDDocument7 pagesZANZIBAR TELECOM COMPANY Vs HAIDARI RASHIDOmar SaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Ateneo de Davao University College of Law JournalDocument288 pagesAteneo de Davao University College of Law JournalMich GuarinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation 1 (About LGBT)Document12 pagesPresentation 1 (About LGBT)April Joy Andres MadriagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Casebook On Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare Volume Ii: 1962-2009Document888 pagesCasebook On Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare Volume Ii: 1962-2009Eliran Bar-El100% (1)

- 1.4 Ethics and ConfidentialityDocument29 pages1.4 Ethics and ConfidentialitydnshretroPas encore d'évaluation

- Lok Sewa AayogDocument5 pagesLok Sewa AayogLokraj SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Complaint-Order For DetentionDocument7 pagesComplaint-Order For DetentionGoMNPas encore d'évaluation

- Governor's Office For Atlantic Beach ElectionDocument3 pagesGovernor's Office For Atlantic Beach ElectionABC15 NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Appeal of Gacis appointmentDocument8 pagesAppeal of Gacis appointmentnyxcelPas encore d'évaluation

- Memorandum of Law - FormDocument4 pagesMemorandum of Law - FormGodofredo SabadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Book ReportDocument6 pagesBook Reportapi-645652649Pas encore d'évaluation

- Betty Friedan's Impact on Second-Wave FeminismDocument5 pagesBetty Friedan's Impact on Second-Wave FeminismAllan JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit-3 Institutional BuildingDocument11 pagesUnit-3 Institutional Buildingprabeshkhatiwada44Pas encore d'évaluation