Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Stanford Journal of Public Health Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Transféré par

stanfordjphCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Stanford Journal of Public Health Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Transféré par

stanfordjphDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Stanford Journal of Public Health

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Investigation

Emma Makoba

In the Midst of Social Stigma and Violence: A Look at Attacks against Persons with Albinism in Tanzania

Policy

Eileen Mariano

Childhood Obesity: A Growing Epidemic

Experience

Christina Wang

Hepatitis B Eradication: An Unsolved Challenge

Stanford Journal Public Health

An Undergraduate Publication Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013 sjph.stanford.edu

of

Jessie Holtzman Emma Makoba Emily Cheng Christina Wang Gianni Sun Andrew Liao

Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Internet Marketing Manager Campus Marketing Manager Financial Manager Layout Director

letter from the editors:

Jessie Holtzman and Emma Makoba editors-in-chief Since the Journals founding e would like to extend in 2011, we have had the pleaa warm welcome to the Winter sure of working with dedicated 2012-2013 issue of the Stanford faculty and staff from all corJournal of Public Health, a bian- ners of the campus, including nual undergraduate publication the Stanford Office of Commuthat seeks to connect the enthu- nity Health, the Center for Insiastic, widely distributed public novation in Global Health, the health community at Stanford Program in Human Biology, by encouraging scholarly dis- the Haas Center for Public Sercussion of todays most perti- vice, Stanford Service in Global nent public health issues. As the Health, and the Sexual Health journal enters its third year, we Peer Resource Center. We would are thrilled by the growing inter- like to acknowledge the generest in the public health field at a ous support of The Bingham university that has traditionally Fund for Student Innovation in lacked a unified forum through Human Biology and the ASSU which to address this topic. We Publications Board. feel that this journal fosters the During a recent lecture, Dean spirit of Stanford University in Lloyd Minor of the Stanford its innovative, academic, and in- University School of Medicine terdisciplinary efforts. proposed three basic tenets of

research review

Jennifer Jenks Liz Melton

experience

Lauren Nguyen Madeleine Kane

policy

Jean Guo

investigation

Caroline Zhang Charlotte Greenbaum

graphics

Judith Shanika Pelpola

innovation: combination, collaboration, and chance. Public health is an interdisciplinary field that combines economics, medicine, biology, and public policy. It requires the collaboration of experts across disciplinary and departmental boundaries to provide a robust analysis of a given research question. Yet, Minor argued that, even together, we can only do so much until we open ourselves to the unexpected. By drawing on many different approaches to public health, the Journal hopes to promote the unexpected and encourage the spark of chance. May you encounter new ideas and perspectives as you read this latest issue. Warmly, Jessie Holtzman 14 Emma Makoba 14

writers

Christina Wang Yifei Men Eileen Mariano Judith Shanika Pelpola

with support from

The Bingham Fund for Student Innovation in Human Biology ASSU Publications Board Haas Center for Public Service

HOLTZMAN

Jessie is a Human Biology major with a concentration in the cellular basis of human disease, combining her passions for policy and the natural sciences. She hopes to use her biology background, along with her interest in womens and childrens health, to develop effective policy solutions to growing local, national, and international health disparities. Through the Journal, she looks forward to spreading awareness of public health topics and proposing new, innovative, interdisciplinary ways to address such dilemmas. Emma is an Anthropology major with a concentration in Medical Anthropology and a Human Biology minor. She will attend medical school at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York through the Humanities and Medicine Early Acceptance Program. She is interested in exploring the important cultural considerations necessary to improve patient and doctor interactions both in one-on-one clinical settings and in the implementation of broader public health initiatives.

Cover photo courtesy of Jessie Holtzman

Logo courtesy of Kiran Malladi Stanford Journal of Public Health

MAKOBA

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

letters from the advisors

contents

Investigation

Public Health Interventions in the Midst of Social Stigma and Violence: A Look at Attacks against Persons with Albinism in Tanzania............................................................... Emma Makoba The Parkinsons Voice Initiative: Early Diagnosis for Parkinsons Disease through Speech Recognition................................................ Yifei Men

Catherine A. Heaney, PhD, MPH Associate Professor (Teaching) Stanford Prevention Research Center

Policy

in print. As always, the Journal is dedicated both to providing an outlet for undergraduates to publish their research and perspectives on public health issues and to bringing important contemporary issues in public health to the wider undergraduate community. As the Journal continues to grow, it has now merged with Stanford Service in Global Health, and in doing so it has added a new Experience section. Because many students wish to pursue professional and programmatic roles in public health as well as scholarly ones, this new section is dedicated to creating a forum for students to share their own personal on-the-ground experiences. The Journal thanks you for your ongoing interest and support.

Grant Miller, PhD, MPP Associate Professor of Medicine; Associate Professor, by courtesy, of Economics and of Health Research and Policy and CHP/PCOR Core Faculty Member

I am delighted to see this academic years first issue of the Stanford Journal of Public Health appear

Childhood Obesity: A Growing Epidemic........................................................................................... Eileen Mariano

13 15

Medi-Cal 2016: What Obamacare Means for California Patients.................................................... Judith Shanika Pelpola

Experience

The Ethics of Striking: A Public Health Concern................................................................................ Jessie Holtzman Hepatitis B Eradication: An Unsolved Challenge............................................................................... Christina Wang

18 20

Research Review

Polio Eradication in India: Lessons for Pakistan?.............................................................................. Ravi Patel

Amy Lockwood Deputy Director Stanford University Center for Innovation in Global Health

23

Infertility: A Plague Gone Unnoticed.................................................................................................. Nitya Rajeshuni

27 33 38

Can Schools Prevent the Next Pandemic: A Study of School-located Influenza Vaccination in Metro Atlanta, Georgia...................................... Julia Brownell

IVF Coverage: A Policy and Cost Conundrum................................................................................... Elizabeth Melton

Stanford Journal of Public Health

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Public Health Interventions in the Midst of Social Stigma and Violence

The

section of the SJPH presents and analyzes pressing public health issues through the lens of epidemiological, medical, and scientific perspectives.

investigation

In this issue, we investigate critical advances in computational technology available to aid in the diagnosis of chronic, degenerative diseases like Parkinsons disease and explore the background and consequences of attacks against individuals with Albinism in Tanzinia.

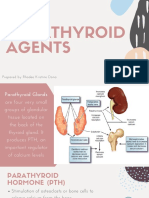

Photo Courtesy of Emma Makoba This is a photo of a higher security elementary school located in Bukoba, Tanzania where many children with albinism from different parts of the region were moved to in order to ensure their safety.

A Look at Attacks against Persons with Albinism in Tanzania

recent years, a disturbing phenomenon of the systematic killings of persons with albinism in certain parts of East Africa has been documented by both academics and the global media. The motivation behind these attacks in parts of Tanzania involves a highly complex system of social tensions that have erupted in violence against children and adults who have this genetic condition. FurtherVolume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

In

Emma Makoba

more, the practice continues today because the limbs and body parts of persons with albinism can be sold at prices ranging from US $500-2000 on the black market. In addition, there is overt discrimination against persons with albinism due to widespread and persistent misunderstanding and misinformation about albinism. This situation serves as an important and tragic example of the need for public health interventions to help improve and protect the lives of innocent but stigmatized and marginalized groups of individuals. More specifically, in regions where persons with albinism have faced violence, they endure not only many health problems resulting from the disease itself such as vision impairment and high susceptibility to skin cancer, but they also suffer life threatening injuries as a re-

Stanford Journal of Public Health

Photo Courtesy of Emma Makoba Pictured is a young boy who was attacked and mutilated by individuals seeking to sell his limbs on the black market for sizable cash rewards.

sult of attacks and often require physical therapy, rehabilitation, and prosthetics if they suffer loss of limbs. Yet, difficulties remain to ensure that persons with albinism have access to the necessary health and rehabilitation services because of both a lack of health infrastructure, as well as the persistent and severe stigma and threats against them. There is an unusually high incidence of occultocutaneous albinism type II, the most severe and the most common type of albinism in Sub-Saharan Africa. The cause for this condition is largely unknown. It is defined biomedically as a genetic condition that causes the defective production of melanin resulting in the lack of pigmentation in the skin, hair, and eyes, vision prob-

lems, and a high susceptibility to skin cancer.1 In Tanzania, it is estimated that the number of persons with albinism ranges between 8,000 and as many as 170,000 individuals in a population of 45 million. If the higher end of the estimation is to be believed, this would make the rate of albinism in Tanzania, approximately one in three thousand as opposed to one in twenty thousand [in] Europe and North America.2 The high concentration of murders and attacks on persons with albinism primarily in northwestern regions of Tanzania began in early 2007. As many as 54 individuals were killed within two years; and to date, a total of 71 murders have been documented.2 Many more

persons with albinism were left disabled due to the attempted dismemberment of their bodies. It must be noted that the actual number of persons with albinism killed and attacked during this time span may never be accurately known and is likely much higher, due to the lack of reporting and documentation in many rural regions of the country. The attacks took place primarily in a particular region of northwestern Tanzania referred to as Sukumaland, in the areas surrounding the cities of Mwanza and Shinyanga. According to Deborah Fahy Brycesons article Miners Magic: Artisanal Mining, the Albino Fetish and Murder in Tanzania, the killings of persons with albinism in this region, are said to trace back to myths perpetuated by witchdoctors, referred to as waganga in Swahili.3 The myth that was disseminated and perpetuated by the waganga is that the body parts of persons with albinism can be used to make a potion which when consumed or bathed in, will bring an individual wealth, luck and success.3 However, many other myths surround persons with albinism, such as the idea they are ghosts, sub-human, immortal, or that their condition is contagious. The physical symptoms of albinism take on a social function in that they set them apart from others within the population that do not share the physical symptoms of the genetic condition. Furthermore, because of their susceptibility to skin cancer, many persons with albinism avoid sunshine, and are thus seen as weak and sedentary in a social context that often deStanford Journal of Public Health

mands hard physical labor in either the dominant mining industry or the agricultural fields in the area. Albinism is not just a genetic disease, but also a socially constructed illness experience in which individuals afflicted are highly stigmatized, dehumanized, discriminated against, and hunted. The persons with albinism do not only endure the physical symptoms of a lack of pigmentation, visual impairment, and increased risk of skin cancer, but they also live in continual fear for their lives because of socially constructed beliefs

that their body parts bring about good luck. Furthermore, having a child with albinism can cause a family to fear for the childs life, seek out ways to keep the child safe, ostracize, or kill the child because the risk may be too great or the family may see the child as not human. Persons with albinism may be deprived of education or job opportunities because of the falsely held belief that their condition is contagious. Children may be forced to stay home from school because leaving the house would put them in jeopardy from people who could potentially attack

and dismember them. Once the complexities of the practice of murdering and attacking persons with albinism in the Sukuma context is understood, it becomes clear the extent to which persons with albinism are victimized. This, in turn, provides a better context to comprehend and address other difficulties that persons with albinism face and how a public health intervention to improve the lives of persons with albinism in this context must take into account the degree to which their health needs are neglected because of social stigmatization.

To find references for this article, please refer to the end of this section.

The Parkinsons Voice Initiative: Early Diagnosis for Parkinsons Disease through Speech Recognition

Yifei Men

arkinsons disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting 6.2 million people globally.4 It is most prevalent in the elderly, though 5-10% of diagnoses reflect early-onset Parkinsons disease. For some individuals, symptoms may begin as early as age 20.4 Early warning signs of Parkinsons disease usually involve impairment of movement, including uncontrollable shaking, rigidity, difficulty walking, and unsteady gait. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral complications may arise, commonly leading to dementia.5 There are currently no cures for Parkinsons disease, and the Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

exact mechanisms leading to the loss of brain cells observed in patients are largely open to debate. Medications, surgery, and multi-disciplinary treatment, however, are widely adopted for relief of disease symptoms. Drugs are especially effective in delaying degeneration of motor functions. For instance, the average time between initial disease onset and complete dependency on care-givers increases from 8 years without treatment to 15 years with regular usage of a single drug, Levodopa.6 However, pharmacological interventions must be initiated in early stages of disease in order to be efficient, as motor symptoms progress aggressively in the early stages if left untreated, leading to irre-

versible disabilities. Effective treatment and early diagnosis for Parkinsons disease are hindered by a lack of quantifiable biomarkers and objective measures of disease progression. As there are no diagnostic lab tests available for Parkinsons disease, the current goldstandard for diagnosis relies on an in-clinic neurological test and brain scans to rule out other

Photo Courtesy of ParkinsonsVoice.org PVI: A new model for diagnosis of Parkinsons based on speech recognition and machine learning technologies.

neurological causes of symptoms.4 This process is extremely costly and requires a high level of expertise, placing stress on existing medical infrastructure. With improving life expectancies in developing countries and an aging population in many developed countries, early and accurate diagnosis of Parkinsons disease will undoubtedly pose an increasing challenge for healthcare systems. Researchers have proposed a new model for diagnosis of Parkinsons based on speech recognition and machine learning technologies. Introduced by Dr. Max Little, Chairman of Parkinsons Voice Initiative, this approach requires only a single sound recording of sustained phonation (saying aaah) from patients. Voice processing tools subsequently analyze the sound recordings and compare them to a database of recordings of Parkinsons patients and nonParkinsons patients that serve as a control. The algorithm developed by this research team is able to detect specific variations in sound vibrations linked to vocal tremors, breathlessness, and weakness. By detecting such voice changes that are indicative

of neurological degeneration, the algorithm is able to generate accurate diagnoses and predict disease progression based on the presence and severity of such degenerative symptoms.7 Although the project is still in the early stages of development, preliminary results are promising; the team claims a 99% success rate in positive diagnoses of Parkinsons disease.8 Accuracy aside, the proposed modality of diagnosis has significant benefits over conventional analytical methods. The research team has not published exact cost estimates, but the method is predicted to be ultralow-cost once it is marketed and fully operational. As the process of analysis is computerized, no medical professionals or additional administration are required for analysis and final diagnosis. This approach is thus very attractive to areas with lessdeveloped medical infrastructure. Speech-based tests can also be easily scaled-up in response to higher demands by increasing computational capacities. Since voice recordings can be readily obtained and transferred using existing telecommunication systems, remote diagnosis

is also possible, increasing access to rural areas or regions with poor healthcare programs. Remote testing also makes largescale screening feasible in areas without the capacity to support high numbers of clinical consultations. Experts suggest that voicebased diagnosis will likely improve early intervention and management of Parkinsons disease. Scientists have long suggested that voice degeneration may be one of the first detectable symptoms of Parkinsons disease.10 Detection of voice changes in Parkinsons disease patients would make it possible for earlier intervention before the onset of disabling physical symptoms. Treatments in the early stages of the disease are critical to delay further aggressive and irreversible neurological degeneration. Voice changes may also serve as an easily assessable and objective proxy to determine disease severity and monitor early trajectories of disease progression. Disease progression is routinely monitored using the 176-point Unified Parkinsons Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS),9 in which patients are scored in categories such as mood, behavior, mo-

tor skills, and ability to carry out daily tasks. However, this assessment requires long interviews and necessitates frequent clinical visits. Although speech tests will not be able to fully capture the degree of physical and mental disability assayed by the UPDRS, they may serve as a proxy to reduce the number of clinical visits and become a lowcost alternative to the UPDRS in resource-scarce regions. While the project holds great promise, it still faces many challenges. Current studies make use of high-quality sound recordings collected in laboratory settings. Although the algorithm remains Photo Courtesy of iStockPhoto.com robust when laboratory-recordThe diagnosis of Parkinsons disease may soon be just a phone call away. ed clips are distorted artificially, it is considerably more difficult initiative has already garnered cal infrastructure or access to to filter out ambient noises that more than half of its target of well-trained professionals. The development of this initiative may confound performance.8 10,000 recordings to date.7 The Parkinsons Voice Initia- also reflects a greater movement The Parkinsons Voice Initiative is currently pooling clips of tive is a promising new approach of data-driven medicine, where phonations sent in by volunteers to facilitate effective early diag- advancements in computational around the globe to build a more nosis of Parkinsons disease. The technology are becoming indisextensive database and formu- cost and capabilities of the initia- pensable in formulating effeclate more precise algorithms for tive are particularly attractive to tive diagnostic and management diagnosis and prediction. The regions without a strong medi- protocols in medical settings. 1. Makulilo, Ernest Boniface. Ablino Killings in Tanzania: Witchcraft and Racism? M.A Thesis, Department of Peace and Justice Studies, University of San Diego; 2010. 2. Kiprono, Samons Kimaiyo, ed. Quality of LIfe and People with Albinism in Tanzania: More than Only a Loss of Pigment. Scientific Reports; 2012: 1-6. 3. Bryceson, D.F, ed. Miners Magic: Artisanal Mining, the Albino Fetish and Murder in Tanzania. The Journal of Modern African Studies; 2010 48(3): 354-382. References for The Parkinsons Voice Initiative article

Graphic Illustration by Judith Shanika Pelpola

10

Stanford Journal of Public Health

4. de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinsons disease. Lancet Neurol. June 2006; 5 (6): 52535 5. Jankovic J. Parkinsons disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. April 2008; 79 (4): 36876. 6. Raguthu L, Varanese S, Flancbaum L, Tayler E, Di Rocco A. Fava beans and Parkinsons disease: useful natural supplement or useless risk?. Eur. J. Neurol. October 2009; 16 (10): e171 7. Parkinsons Voice Initiative - Science. Available at: http://parkinsonsvoice.org/science.php. Accessed November 13, 2012. 8. A. Tsanas, M.A. Little, P.E. McSharry, J. Spielman, L.O. Ramig. Novel speech signal processing algorithms for highaccuracy classification of Parkinsons disease. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2012; 59(5):1264-1271. 9. Ramaker, Claudia; Marinus, Johan, Stiggelbout, Anne Margarethe, van Hilten, Bob Johannes. Systematic evaluation of rating scales for impairment and disability in Parkinsons disease. Movement Disorders. September 2002; 17 (5): 867876 10. Hanson, DG, BR Gerratt, and PH Ward. Cinegraphic observations of laryngeal function in Parkinsons disease. Laryngoscope. March 1984; 94 (3): 348-53.

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

11

Childhood Obesity: A Growing Epidemic

The SJPH explores the intersection of public health research and innovation and its deployment in the real world. The section approaches health topics at the forefront of scientific debate by integrating legislative, ethical, and economic perspectives. In this issue, the Policy Section explores regulation of public health issues at the state and national levels, investigating the consequences of the Affordable Care Act on Medi-Cal patients and various interventions to address the growing childhood obesity epidemic.

policy

Eileen Mariano

section of the

ven though the HIV virus transferred from monkeys to people in the 1920s, there were eight million people living with the disease by 1990. At that time, with no cures yet definitively proven and a steady climb in the number of diagnoses, HIV/ AIDS appears to be one of the worst epidemics to ever plague the United States. However, at the turn of the 21st Century, yet another problem has taken center stage in the battle for the future health and wellbeing of Americans. Over the past few decades, healthcare professionals have grown increasingly concerned with childhood obesity, an epidemic now affecting an unprecedented proportion of the American population. More than one third of children and adolescents in the United States were overweight or obese in 2008, and that number has not shown any signs of decline.2 3 In fact, since the 1970s, the childhood obesity rate has tripled.4 As a result of this increase, it is estimated that the generation currently in their childhood will be the first in American history to live shorter lives than their parents.5 Healthcare providers worry about obesity because it is closely associated with diabetes. Specifically, Type II diabetes may lead to blindness, hypertension, an increased risk of heart problems, and in extreme cases, Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

amputation of digits and limbs. For these reasons, obesity and obesity-related illnesses are the leading cause of death in the United States every year, and it is estimated to shorten lives by an average of twelve years.6 Further, the harm of childhood obesity and diabetes transcends the physical symptoms alone. Those who suffer from obesity are also impacted by social discrimination, to the point where individuals have difficulty finding jobs, participating in activities, and even forming desired relationships.7 At a national level, the obesity epidemic has become a national security threat because up to one-quarter of the people trying to join the military are unqualified because of their weight.8 In addition, it is estimated that obesity-related complications cost the United States health care system $344 billion dollars a year.9 What is already being done to combat this growing, harmful trend? Steps are being taken at both the local and national levels. Locally, many propositions and social movements have been enacted. According to Christopher Gardner, Associate Director of Nutrition Studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center and Associate Professor of Medicine at Stanford University there is room to be optimistic. It is sometimes very difficult to make a big change. So what people have started to do is

play around with little changes, as part of the movement and I think its working, Gardner explained. A few examples of the little changes that Gardner refers to include efforts from New York Citys Mayor Bloomberg, who started an initiative that prohibited the purchase of soda using food stamps in New York10, and Measure N in California, the first proposed soda tax in the country to appear on a ballot.11 In addition, Michigan implemented Double Up Food Bucks, an initiative that gives bonus token rewards when people buy fruits and vegetables from farmers markets12, and the Santa Clara County Toy Ban, which states a toy cannot be sold along with a fast food meal unless the meal meets calorie, fat, salt, and sugar content guidelines. Unfortunately, due to specific restrictions and a limited scope, the ban only affected four restaurants. However, it received national attention and was later implemented by San Francisco and proposed by the state of Kansas. Nationally, the Obama administration has made strong efforts to curtail the epidemic. In January of 2012, President Obama announced that he would add $3.2 billion to the $11 billion school lunch program. The extra support would be used to add more fruits and green vegetables to breakfasts and lunches and reduce the

12

Stanford Journal of Public Health

13

amount of salt and fat. Obamas subsidies also provide the funding for whole grains, lowfat milk, and the technology to monitor the amount of caloric intake per lunch per student.13 Michelle Obama has also played a significant role in the effort to reduce childhood obesity, claiming that she is going to continue to do everything that [she] can to focus [her] energy to keep this issue at the forefront of the discussion in this society.14 Specifically, she established her Lets Move! initiative, which encourages nutritional foods, increased physical activity, and a healthy start for children. The campaign has launched numerous movements, which include paying restaurant chefs to move to schools, awarding subsidies to schools that start a vegetable garden, and initiating a summer food program that allows children to eat healthfully year-round. The First Ladys initiatives have encouraged healthier eating and are influencing student lifestyles all over the country.15 But the question remains, are the current local and national level efforts enough to stop an epidemic? Donald

Medi-Cal 2016: What Obamacare Means for California Patients Judith Shanika Pelpola

edicaid, better known as Medi-Cal in California, will cover a greatly increased number of patients by 2016 as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Popularly known as Obamacare, this recent healthcare reform has sparked numerous discussions regarding its effect on the already overstretched Medicaid and Medicare systems. California has decided to opt in to the new program established by the ACA, thus ensuring healthcare coverage under Medi-Cal for all individuals with an income below 133% of the federal poverty line. 1 According to the Washington Post, California expects to enroll an additional half a million people in the program by 2014, with that number increasing significantly by 2020. 2 Medi-Cal, like other Medicaid programs across the nation, was originally created for those eligible for welfare, specifically the elderly, the disabled, and single parents with young children. It was set up as a program not for all poor people but for only certain categories of poor people, and it was originally tied to whether you got welfare checks, Don Barr, a professor of Human Biology at Stanford, said. Once a state signed up for the program, it was required to support every person in the above categories. Poor was defined in different ways for each of those Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Graphic Illustration by Judith Shanika Pelpola

Barr, Physician and Associate Professor of Sociology and Human Biology at Stanford University, does not think so. He pointed out, if you think its a problem now, its about to be an even bigger one, which is why local, state, and national level government need to increase their efforts, given the severity of the epidemic. To put the anti-childhood obesity efforts into perspective, in 2008, the federal government committed to spending $48

billion over the next five years on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment efforts. This aid will affect the 1.2 million people living with HIV in the US.16 There are, comparatively, 9 million obese children. Despite the current local and national efforts to reduce childhood obesity, those initiatives are not sufficient. Preventing the expansion of this epidemic is a crucial step toward a healthy future for Americans.

Donald Barr is a physician and an Associate Professor of Sociology and Human biology at Stanford University. He researches a wide variety of topics, one of which is the social and economic factors contributing to health disparities, and specifically to obesity. Christopher Gardner is the Director of Nutrition Studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center and an Associate Professor of Medicine at Stanford University. He received his PhD from the University of California and now researches dietary intervention and the way that food increases disease risk factors and body weight.

To view the references for this article, please refer to page 43

groups but if you were not in those three groups, even if you were extremely poor, you got zero coverage, explained Barr. Thus many low-income individuals often go without healthcare coverage unless their employers provide it. The federal government partially supports Medi-Cal, basing contributions on the average per capita income in the state. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the federal government pays 50% of Medi-Cal costs as of 2012. 3 California covers the remaining 50%, a financial burden that has strained the budget and made it difficult to expand Medi-Cal to other low-income individuals. This affects many other states, though lower-income states receive up to a 75% subsidy of costs from the federal government. By setting an income level of 133% of the federal poverty line, the ACA makes healthcare coverage available for most lowincome people below the specified income level. Currently, the eligible income level in California is around 60% of the federal poverty line, as calculated using Medi-Cal monthly income requirements divided by the poverty line (see 2012 HHS Poverty Guidelines). 4 The Affordable Care Act has said, lets get away from this idea of this being only

for certain categories of poor people; lets make it for all poor people, claimed Barr. In raising the minimum income level, the ACA also eliminates shares of cost for many Medi-Cal and other lower-income patients. The share of cost program applies to those above the minimum income level who still qualify as low income, holding these patients financially responsible for a share of their medical expenses. However, this means that even those who were at 61% of the federal poverty line were forced to pay a share of cost, which is applied before Medi-Cal payment covers the remaining cost of care. 5 With the ACA, any individual or household earning up to 133% of the federal poverty line, currently $15,130 per year for a family of two or $1260 a month, will no longer have to pay healthcare costs. According to the Kaiser Family Foundations summary of the ACA, even those above this line will receive subsidies to help purchase coverage in the private sector. One concern with regard to the ACA is the increase in cost that the program will incur. States like California will continue to cover the cost of patients under the original program, while the federal government will cover all incoming patients for the first few years. By 2020, states will

14

Stanford Journal of Public Health

15

cover 10% of the cost of the new patients, while the federal government covers the remaining 90%. 7 In the long run, the ACA is expected to reduce the federal deficit in part by reducing costs incurred by county hospitals and clinics, which provide uncompensated care for those who do not qualify for Medi-Cal. According to the Milken Institute, California hospitals provided $12 billion in uncompensated care in 2009.8 Uncompensated care is supported only in part by payments from the federal government. In making previously uninsured, low-income patients eligible for Medi-Cal, the ACA ensures that many hospitals and doctors that provide such services will be compensated. All

of a sudden the hospitals and the doctors have a source of payment for these people, clarifies Barr. However, a shortage of doctors and care facilities is expected in places like the Veterans Hospital in Palo Alto, which accept Medi-Cal as payment. According to Barr, this continues to be a very serious problem since Medi-Cal pays doctors less than 70% of what Medi-Care pays, and Medi-Care pays about 80% of what the private market pays. That means its less than half of the usual charges, so lots of doctors just say were not going to take Medi-Cal. This puts strain on community clinics to which Medi-Cal patients turn. According to the New York Times,

the Inland Empire of Southern California has only half of the number of recommended primary care physicians for its population. 10 This is a common concern across California counties. While the ACA provides for roughly 15,000 new doctors in community clinics nationwide, anxiety still remains regarding the number of primary care doctors for newly eligible patients. According to Barr, the question remains regarding the shortage of primary care doctors for new Medi-Cal and Medicaid patients across the country. Thats the issue that is unclearThere are things in the Affordable Care Act to expand community clinic delivery systems and well see if thats going to be adequate.

The

section of the SJPH presents public health challenges that students have encountered personally, highlighting the relevance of such issues to student life on a day-to-day basis. In this issue, our articles explore a range of interests sparked by our writers experiences, from local to international, including the ethics of Spanish healthcare workers striking and the benefits of lobbying legislators to achieve awareness and prevention goals with respect to hepatitis B.

experience

Donald Barr is a physician and an Associate Professor of Sociology and Human biology at Stanford University. He researches a wide variety of topics, one of which is the social and economic factors contributing to health disparities, and specifically to obesity.

1 Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ ppacacon.pdf. 2 Kliff, Sarah. Obamacares Medicaid Expansion Already Covering a Half-Million Americans. Washington Post. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/ 2012/07/03/obamacares-medicaid-expansion-already-covering-a-half-million-americans/. Accessed November 30, 2012. 3 Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Financial Participation in State Assistance Expenditures. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/fmap12.shtml. Accessed November 30, 2012. 4 Department of Health and Human Services. 2012 HHS Poverty Guidelines. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/ poverty/12poverty.shtml. Accessed November 30, 2012. 5 California Healthcare Foundation. Share of Cost Medi-Cal. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/ ~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/S/PDF%20ShareOfCostMediCal2010.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2012. 7 Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of Coverage Provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8023-R.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2012. 8 Milken Institute. Medicaid Expansion May Cripple Californias Burdened Health System. Available at: http://www. milkeninstitute.org/newsroom/newsroom.taf?function= currencyofideas&blogID=523. Accessed November 30, 2012. 9 Lowerey, Annie and Robert Pear. Doctor Shortage Likley to Worsen with Health Law. New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/29/health/policy/too-few-doctors-in-many-us-communities.html?_r=2&. Accessed on November 30, 2012.

16

Stanford Journal of Public Health

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

17

Jessie Holtzman

The Ethics of Striking: A Public Health Concern

healthcare budget in an attempt to revive the floundering economy. Starting in 2000, Spain became an increasingly popular country for immigration due to the generous benefits provided to immigrants. Immigration came with benefits, helping to maintain the population as the countrys growth rate fell to 1.1 children per couple. It came with costs as well, though. The country became a frequent destination for healthcare tourism, with residents of other European Union countries traveling to Spain for its superior healthcare procedures at low costs. As of August 2012, the government no longer provides free healthcare services to undocumented immigrants, and healthcare tourists must reside within Spain for more than three months before receiving free healthcare services.3 Now, the system only provides healthcare to foreigners in cases of grave illness or accident, pregnancy and birth-related care, and to those younger than 18. These changes discourage non-tax-paying residents from using the healthcare system, a worthwhile policy to prevent unfair exploitation of tax-paying citizens. However, further broad cuts to the rest of Spanish society come at a time when Spanish unemployment has climbed to dangerously high levels. Spaniards are paying an increasingly large percentage of their healthcare costs directly, while their salaries are dropping to historically low levels. Retired citizens now contribute a 10 percent copayment toward the costs of medicine, while non-retired citizens pay between 40 and 60 percent copayments, scaled to income level. Citizens now pay for wheelchairs, crutches, and splints, as well as non-urgent transport to hospitals.3 The most controversial element of the recent changes to Spanish public health financing is the Fiscal and Administrative Measures Law, implemented on January 1, 2013. This legislation aims to privatize six major hospitals in Madrid, as well as 27 non-urgent health clinics. In addition, the measure adds a one Euro fixed supplemental charge to the cost of each prescription medication. These proposed changes sparked heated debate, with left-wing deputy Antonio Carmona saying, Privatizing healthcare isnt efficiency; its business. This isnt law; it is a scandal.4 Doctors and nurses went on strike for five weeks before the passage of the law, leading to the cancelation of more than 40,000 patient visits and a 1.74 billion Euro loss in 2012 from work stoppages. Although experts agree that the Spanish public health system needs reform, healthcare workers fear the consequences of these changes. Spanish doctors and nurses see these changes as threatening Stanford Journal of Public Health

late November, more than 75,000 healthcare professionals gathered in Puerta del Sol, in the heart of Madrid, holding signs that read health care cuts kill and public health: not for sale.1 Amidst new austerity measures, these employees were striking to protest a set of cuts particularly worrisome to the public health community. With the Spanish economy in crisis, the conservative government of President Rajoy announced that Spain needed to cut 10 billion Euros of health and education spending each year starting in 2012. Seven billion Euros worth of these cuts are taken from the healthcare budget.2 Spaniards, and specifically members of the healthcare sector, have reacted strongly to this reduction, since it targets a key element of the prized welfare state that developed in the 1970s transition from dictatorship to democracy. While these workers have good intentions and many valid concerns, their strike hurts the patient population rather than targeting the government violating their rights. Instead of striking, doctors and nurses should take up more productive ways of demonstrating dissatisfaction to avoid punishing the patient population for government austerity decisions. With the current state of crisis, the Spanish government must make cuts to its extensive

In

their practices and patients. The healthcare sector claims that it protested not due to a threat to working conditions or privileges, but rather for the right of everyone to have access to quality healthcare. Doctors fear that the changes jeopardize the delicate balance of healthcare expenditure, quality, and benefit in favor of a better business arrangement. They point to claims by government administrators that hospital expenditures per capita will decrease from 600 Euros to approximately 450 Euros.3 Where the measure calls for cuts in treatments with lower proven efficacy, doctors fear that eliminating procedures to save money could reduce quality of care and ease of access. Yet, the extended striking of doctors and nurses, la marea blanca, raises questions about the obligation of health professionals to provide quality healthcare. This essential service sector has a right to negotiate for acceptable working terms, but patients also have a right to expect uninterrupted access to care. The strikes effect of stopping

all non-urgent care challenges the patient-physician contract, which requires that physicians act responsibility and provide continuing care to patients. Doctors have a fundamental obligation to treat their patients to the fullest extent possible, so alternative methods of manifesting dissatisfaction toward the government would be preferable. However, effective non-striking options require fundamental trust between the two parties, which is currently absent in Spain. Historically, Spaniards do not trust the government due to the high levels of corruption and nepotism that lead to concerns about the motives behind government decisions. Nevertheless, given the ethically dubious nature of healthcare professionals striking, the government and the unions must put aside their differences to achieve a feasible level of budgetary cuts in this time of dire economic crisis. The associated doctors of one of the healthcare unions issued a statement saying, We need the patients to know that we do this for them, because

we know the depravity of the systems of incentives in private healthcare. It is a question of responsibility.4 The doctors claim to act out of care for patients rather than interest in their own compensation. Indeed, by striking, union workers accept fines and decreased salaries, in return for calling attention to what they see as unfairly imposed austerity measures. While some patients may agree with the doctors and support the strikes, though, the health care strikes harm the patient population, with the cancelation of thousands of procedures. Striking on behalf of the patient population surely makes a public statement about the dissatisfaction of physicians and nurses, but it also jeopardizes the goal of the public health system to ensure the conditions in which people can be healthy.5 Healthcare workers are essential to society, and as such, their union rights cannot be ignored. Ultimately, a doctors right to strike cannot, and should not, be entirely eliminated. Nevertheless, this does not mean that a strike is the best option.

1. Thousands protest austerity measures in Spain. RT [online]. December 18, 2012. Available at: http://rt.com/ news/spain-union-protest-mass-228. Accessed December 28, 2012. 2. Day, Paul. Spain seeks health care cuts as crisis deepens. Reuters [online]. April 18, 2012. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/18/us-spain-health-idUSBRE83H0LX20120418. Accessed December 9, 2012. 3. Los recortes sanitarios, uno a uno. El Mundo [online]. April 25, 2012. Available at: http://www.elmundo.es/ elmundo/2012/04/24/espana/1335249973.html. Accessed December 14, 2012. 4. Sevillano, Elena. El bastion de la marea blanca. El Pais [online]. November 10, 2012. Available at: http:// ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2012/11/10/madrid/1352585971_ 718417.html. Accessed December 12, 2012. 5. The Future of the Publics Health in the 21st Century. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies: November, 2002.

18

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

19

Hepatitis B Eradication: An Unsolved Challenge

Christina Wang

knowing that one in ten people around me suffered from hepatitis B. It wasnt until I came to college that I learned what hepatitis B is and that this disease is in fact ten times more prevalent that AIDS, and 100 times more infectious.1 My childhood ignorance is a testament to the evasive nature of this virus to community public health efforts. Hepatitis B mostly affects Asian Pacific Islanders, a demographic that only comprises six percent of the United States population. In a country that frequently focuses on public health efforts that will affect populations that comprise

I grew up in China without

a greater proportion of society, hepatitis B does not constitute a significant enough threat to motivate sizeable involvement by the public health community. In addition, a vaccination for hepatitis B exists and has been widely implemented. The urgency of addressing hepatitis B lessened beginning in 1992, when all newborns began to be vaccinated against this virus. Thus, for young, American-born individuals, hepatitis B no longer poses an immediate threat. However, in port cities including San Francisco and New York City, immigrants from highly afflicted countries are constantly arriving, warranting continued

focus on this topic. Additionally, the asymptomatic nature of hepatitis B leads to continuing concern, as patients do not know they are infected until they are already significantly ill. As a member of Team HBV, an intercollegiate organization that seeks to eradicate hepatitis B in nearby communities, I have experienced all of these barriers to hepatitis B awareness efforts, first-hand. The goal of the organization is to educate Stanfords campus members through events like the Screening Initiative Program. The premise is simple: visit Vaden Health Center, provide documentation to show that hepatitis B

Graphic Illustration by Judith Shanika Pelpola

screening was performed, and receive a reward. Analysis of the results of 80 test subjects left the organization both optimistic and perplexed. None of the 80 students who had been screened for hepatitis B tested positive. Clearly, Team HBV was not targeting the right audience, as the majority of the test subjects were Stanford undergraduates, born on or after 1992 and who had been vaccinated. Though on campus screening proved to be a rather ineffective measure to reduce hepatitis B prevalence, the organization still wanted to increase on-campus awareness of the disease and its prevalence in a tangible manner. Thus, Team HBV organized a Hepatitis B Awareness Week, during which flyers illustrating hepatitis B facts and a schedule delineating a weeks worth of educational events were distributed across campus, attached to balloons in order to call attention to the event. Yet all of these efforts proved to be largely ineffectual. Some students may now be cognizant of the existence of hepatitis B and the organizations efforts dramatically increased the occurrence of on-campus screening, but the overall effects were strictly limited to the Stanford campus. Despite the narrow improvements on the Stanford campus, other eradication efforts worldwide have shown significantly more promise. I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to organize

World Hepatitis Day in the summer of 2012. The World Hepatitis Alliance challenged viral hepatitis organizations across the world to participate in a Guinness World Records Challenge of having the most people performing see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil actions in numerous venues around the world, over a 24hour period. A total of 50 Team HBV high school and college students came out to the Crissy Field location in San Francisco on July 28th, 2012. The worldwide event was featured in articles in the World Journal and the Tsingtao News, the two largest circulating newspapers among the ChineseAmerican population in San Francisco. The publicity that this event received shed light on a more effective method through which to target the population at risk: reaching out to the local media. Not only were we able to communicate directly to the highest risk population in the Bay Area, but we were also communicating to them in their language, through media sources that they trusted. A second event that proved effective was a service trip that addressed the subject of hepatitis B in San Francisco. One of the trip days highlighted advocacy efforts by splitting the group in half and rallying legislative offices to raise awareness of hepatitis B. While the group members were initially skeptical of the potential impact of this type of advocacy work, the

majority of students came out feeling that the representatives of elected officials had heard and understood the message that they were sending. While state budgets were a constraining factor, the offices told the students that they would do their best to advocate for hepatitis B screening in the future. Most interestingly, many of the representatives reported that they had not heard of hepatitis B prior to the students visit, which raises the question, if these elected officials had not heard of this critical public health issue before, how can we expect their constituents to be aware of the disease? The experience of Team HBV highlights the efficacy of discussing key public health issues with legislative offices. In particular, Senator Feinsteins office noted that they greatly enjoy student input because student constituents are not paid for the messages that they deliver, but rather do so out of sheer interest and concern. Team HBV has approached their goal of the eradication of hepatitis B through a variety of methods, several of which offer fresher and arguably more effective methods than on-campus education. While the latter remains an important tactic, the battle with hepatitis B will require use of a wide variety of broadly targeted avenues to educate a greater percentage of residents in the United States. The sooner that awareness is raised, the sooner hepatitis B will be eradicated.

20

Stanford Journal of Public Health

1. Liu, J. and Fan, D. Hepatitis B in China.The Lancet. 2007;369(9573): 15821583. Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

21

Polio Eradication in India:

The

invites the members of the Stanford community to share their essays, perspectives, and research with a broader audience interested in public health. In this issue, we present a highly varied collection of research from the undergraduate community that addresses national and international topics. Our authors have explored topics relating to the effectiveness of school-located influenza vaccination programs, a cost and policy analysis of in vitro fertilization, a comparative policy analysis of polio eradication methods used in Pakistan and India, and techniques to reduce the psychological and economic burdens on infertile women in America.

Ayurvedic or traditional medicine shop. Karachi, Pakistan. December 2011. Photo Courtesy of Ravi Patel

research

Lessons for Pakistan?

section of the SJPH

Ravi Patel

t has been claimed that, apart from the atomic bomb, Americas greatest fear was polio in post-World War II America. However, this American fear was conquered in 1956, when Dr. Jonas Salk developed the first polio vaccine. Salks polio vaccine has been highly effective, and today, it has led to the eradication of endemic polio in all but three countries worldwide: Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. Although separate countries today, Pakistan and India were both carved out in Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

1947 from a single territory then known as British India. As a result of this common heritage, the two countries face similar social, political, and, most importantly, developmental challenges today. Along with similar historical and social contexts, both India and Pakistan share similar per child cost of vaccination, another factor placing Pakistans polio crisis in context of Indias past experiences (Figure 1). Specifically, this paper analyzes the case of polio eradication in India, and in tandem identifies potential lessons for Pakistan in its quest to eradicate polio.

Today, polio can be found in four main areas in Pakistan: FATA (Federally Administered Tribal Areas), Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan (along the border with Afghanistan) as well as in parts of Sindh (Figure 2). These locations also happen to experience the greatest security vulnerabilities from radical Islamic groups such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan. The poor security conditions in these places enable polio to thrive because of difficulties in sustaining a robust public health infrastructure. The vulnerability of polio workers in Pakistan was best illus-

22

Stanford Journal of Public Health

23

Figure 1: Operations costs per Child for SIAs (Supplementary Immunization Activities)18

trated by a series of coordinated attacks in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Karachi by Taliban associated militants in December 2012 and January 2013. In total, 16 health workers were killed, including 12 women, and the U.N. decided to temporarily suspend its operations against polio in the country. Women health workers are essential in Pakistans battle against polio since women in the conservative Pakistani culture, unlike men, can get access to children and other women in the household. The four regions in Pakistan home to polio are tribal in nature, and have large, migrating populations, making vaccine distribution difficult to organize. The Taliban and other fundamentalist Islamic groups have also banned polio health workers from delivering care in certain parts of the county where they exert influence claiming

that these workers are American spies. This misconception was reinforced with a fake polio vaccination campaign in Abottabad carried out by Dr. Shakil Afridi under CIA supervision to obtain DNA confirming Osama Bin Ladens presence. Coupled with this continuing suspicion, many in Pakistan believe that the polio vaccine is a Western rouse to sterilize Muslim. A similar distrust exists in Nigeria, where some religious leaders have called for boycotting polio vaccination because they believe it causes sterility in girls, spreads HIV and cancer. Resistance ultimately led to several northern Nigerian states boycotting the polio vaccine for about 10 months during 2004.7 The fallout of Nigerias struggles with immunization in 2004 not only led to polio spreading to previously polio-free areas in Nigeria, but to also spread to eight polio-free countries surrounding Nigeria. Beyond these existing issues, Pakistan faces poor public health infrastructure and possesses a critical shortage in human resources. Experts have argued that Pakistan faces a massive funding shortfall for polio eradication. So far, Pakistans government has so far only been allocated half of what was budgeted for 2012-13 by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (a public-private partnership led by organizations such as the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to eradicate polio). Clearly, Pakistan faces immense political obstacles as it seeks to eliminate polio. India, Pakistans neighbor to the west, has also faced

a long battle against polio. As recently as 2009, India had the highest number of polio cases in the world.2 Like Pakistan, India faces rampant poverty, high birthrates, large populations, and remotely located communities. Along the same lines, India has weak public healthcare infrastructure, reflected in its poor track record of delivering medical care. For example, India was ranked 112th of 191 by the WHO in terms of its ability to deliver adequate healthcare to its citizens. Despite these challenges, India has implemented measures that such that January 2010 marks the last reported case of polio. Political commitment was the primary change that made India successful in its fight against polio. With political backing from the ruling Congress Party, the Indian government apportioned significant resources to polio eradication campaign. By 2013, India will have invested nearly $2 billion to combat polio. As a result of this political support nearly 170

Figure 2: Map of Polio Hotspots in Pakistan, 201019

million Indian children are immunized through two national polio vaccination campaigns each year. Furthermore, India was effective with targeting nomadic populations by using better mapping technologies in conjunction with the aid of local community workers. Not only did these workers better understand nomadic populations, but they also were able to gain the trust of people they served. Indias robust surveillance and immunization network was crucial to polio eradication operations as well.4 To date, India has 33,700 reporting sites, managed with the assistance of 2.5 million vaccinators.11 The infrastructure established by Indias polio campaign has encouraged additional immunization campaigns. Because of these customized political measures, India has been able to defeat polio, a threat that has dominated the land for hundreds of years. While it is difficult to gauge whether Pakistan will successfully embrace the polio eradication policies exercised in India, it is obvious that failed strategies in Pakistan will require intervention. Polio conditions in India vastly improved subsequent to employing techniques used in neighboring Bangladesh (also carved out from colonial British India like India and Pakistan as well). Bangladesh eradicated endemic polio in 2000. India, in particular, was able to adopt some lessons from Bangladesh (also carved out of British India like India and Pakistan), which eradicated endemic polio in 2000. In the case of Bangladesh, the campaign against polio was particularly successful because Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

Photo Courtesy of Ravi Patel Children playing after receiving the polio vaccine in Sukkur, Pakistan

it was able to build a robust infrastructure monitoring polio. In Bangladesh, more than 90% of cases of acute flaccid paralysis, a clinical symptom of polio, are investigated within 48 hours of notification. Based on these lessons, India was able to improve its polio surveillance network and this move was one of the key factors that help it win its own battle with polio. A simple cut and paste of Indias public health set up may not by itself eliminate polio in Pakistan. These lessons, nevertheless, do highlight crucial changes that would serve as a starting point for Pakistan to be

more effective against polio. In Pakistan, there is political support against polio at the highest levels of government. For example, Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari announced at the UN General Assembly in September 2012 that he and his government would work to make Pakistan polio free. This elite political support has not yet trickled down to the local and provincial level. From my informal conversations with local PPP (Pakistan Peoples Party, the ruling political party) workers in rural Sindh, the persistence of polio can be attributed to the lack of coordination on polio eradica-

24

Stanford Journal of Public Health

25

tion efforts between the districts themselves. Even with widespread political backing, failing to coordinate the battle against polio and provide vaccine access to nomadic communities has caused polio to continue to plague the people of Pakistan. Obtaining greater political support at the local levels might also lead to an improved security environment for health workers because obtaining support from these local leaders lessen resistance from local communities.

Pakistan could develop a robust surveillance and immunization network akin to that of India. Adopting Indias approach will bring Pakistan one step closer to eliminating polio, and potentially other preventable diseases, from its own land. Collaborating with India on polio eradication would reduce, if not eliminate, the polio burden from the country, serving as a bridge in an otherwise frosty bilateral relationship. Furthermore, cooperation on

the polio issue between the two countries could be a conduit for further collaboration on other critical public health issues such as HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis. Perhaps, greater cooperation in public health could have implications for other regional development issues such as the prospect of building more cross border trade. By applying lessons from Indias experiences defeating polio, Pakistan can save more lives from experiencing the effects of this disease.

Infertility: A Plague Gone Unnoticed

Nearly 6 million women and their partners in the US suffer from infertility. Most think it is just another medical problem, but the truth is, the suffering of these victims goes far beyond the biology to the psyche, leaving deep lasting scars. Little has been done to rectify this problem at the policy level. But through an active, multidisciplinary effort, a fresh current of change might just be possible.

Nitya Rajeshuni

change and evolution, womens health is just one more hot-button issue to add to the laundry list of contentious policy battles. In recent years, the debate has become particularly intense, involving heated discussions between various demographics, ranging from men versus women to Republicans versus Democrats to old versus young to even women versus women. However, the issues present in the media every daytopics like abortion and contraceptionare only part of the story. In the shadow of such discussions, other equally important issues in womens health have been masked. When is the last time a major national debate took place regarding funding for research on infertility or health care coverage for its treatment? Has any such large-scale debate ever occurred in the first place? What about the ramifications that often come with inability to start a family? Is it likely that current legislatures will fund treatment of the depression and cases of mental illness associated with

1. The Polio Crusade American Experience. Public Broadcasting Service. 2009 2. John, Jacob and Vipin Vashishtha. Path to Polio Eradication in India: A Major Milestone Indian Pediatrics. Volume 49, Number 2 (2012), 95-98. 3. Muhammad, Peer. Security Situation a risk to anti-Polio effort: WHO. The Express Tribune. 2012. Available at: http://tribune.com.pk/story/419545/security-situation-a-risk-to-anti-polio-effort-who/ Accessed Dec 1, 2012 4. The War on Pakistans Aid Workers. The New York Times. 2013.Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/05/ opinion/the-war-on-pakistans-aid-workers.html Accessed Jan 10, 2013. 5. Walsh, Declan and Donald McNeil Jr. Female Vaccination Workers, Essential in Pakistan, Become Prey. The New York Times. 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/21/world/asia/un-halts-vaccine-work-in-pakistanafter-more-killings.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed Jan 10, 2013 6. Walsh, Declan. Taliban Block Vaccinations in Pakistan. The New York Times. 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/19/world/asia/taliban-block-vaccinations-in-pakistan.html Accessed Dec 1, 2012 7. Tohid, Owais. Move to Get Bin Laden Hurt Polio Push. The Wall Street Journal. 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204190504577038781784474056.html Accessed Dec 1, 2012 8. Personal Conversations with local Pakistani Political Leaders in December 2011. 9. Jegede AS (2007) What Led to the Nigerian Boycott of the Polio Vaccination Campaign? PLoS Med 4(3): e73. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.004007 10. Polio boycott is unforgivable. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2004. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/ africa/3488806.stm 11. Winsten, Jay and Emily Serazin. Victory Against Polio is Within Reach. The Wall Street Journal. 2012. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444025204577546562570306028.html Accessed Dec 1, 2012 12. World Health Report 2000. World Health Organization. 13. UN Health agency marks WPD with renewed efforts to eradicate the disease. Available at: http://www.un.org/apps/ news/story.asp?NewsID=43366&Cr=polio&Cr1=#.UIzLBMXA8kk Accessed Dec 1, 2012 14. Building on Indias Success on Polio. The Wall Street Journal. 2012. Available at: http://blogs.wsj.com/indiarealtime/2012/10/24/building-on-indias-success-on-polio/ Accessed Dec 1, 2012 15. Schaffer, Teresita. Polio Eradication in India: Getting to the Verge of Victory and Beyond? Center for Strategic and International Studies. 2012. 16. USAID/Bangladesh. Polio: On the Brink of Eradication. Available at: www1.usaid.gov/bd/files/polio.doc. Accessed Dec 1, 2012 17. Zardaris Pledge to Polio. Dawn. 2012.Available at: http://dawn.com/2012/09/28/govt-taking-polio-eradication-campaign-seriously-zardari/ Accessed Dec 1, 2012 18. Financial Resource Requirements 2012-2013. Global Polio Eradication Initiative. World Health Organization. 19. Available at: http://www.polioeradication.org/Dataandmonitoring/Poliothisweek.aspx Accessed Dec 1, 2012.

In an era of ongoing policy

infertility when most do not even fund the treatment itself? Infertilitymillions of women across the nation today struggle with this condition; yet, despite the prevalence of this plague and the suffering it brings, their plight has gone severely unnoticed, masked by the ever- present discussion on abortion and contraception. However, one must wonder, if society is so concerned regarding policy covering not only the prevention of birth but of conception, shouldnt the creation of life receive equal attention? Infertility is a major problem in the US, proving not only challenging but extremely expensive and psychologically detrimental, particularly to women. Despite these negative implications, very little policy on the subject has been proposed to date. However, that is not to say that national or state legislation would have very little impact on the issue. Rather, the proposal of such legislation could have much to offer, if constructed in a multifaceted and interdisciplinary manner. Through such an approach, combining both

federal and state efforts, access to psychological services and affordability of treatment could certainly be increased as well as improved. Of course, one must ask, how might we achieve this? Although there is much work to be done, an excellent place to start would be through policy proposals such as the specific bill I have constructed and outlined in this paper.

26

Stanford Journal of Public Health

Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

27

Having a child is a common dream that many women share.

Nearly 6 million women and their partners in the US are infertile, accounting for approximate 10-15% of the entire reproductive population.7 While about 40% of infertility cases can be attributed to male-related factors and 40% to female-related factors, 20% are attributed to a combination of the two, rendering exact diagnosis often difficult.7 Furthermore, even if a particular partner has been identified as the source, diagnosis can prove equally if not more challenging,7 despite the variety of medical treatments available. Approximately 25% of all couples in the US have trouble conceiving.7 Typically, 10-15% can eventually succeed using basic methods, such as regimented sexual intercourse, discontinuation of birth control, and changes in lifestyle, diet, and nutrition. While 80% of those who begin with the basics succeed, the remaining 20% typically move on to fertility drugs, hormonal therapy, and finally assisted conception (intrauterine insemination, in-vitro-fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injec-

tion (ICSI)), posing a disheartening 20% success rate.7 While these treatments offer potential medical solutions to the problem of infertility, issues of mental health have increasingly garnered more attention due to the lack of efforts and funds in this area. A promising, albeit inadequate, amount of research has been conducted, indicating that the mental health of women facing infertility is indeed a very real problem. However, the findings have hardly been applied. According to the Department of Health and Human Services 2010,4 the seven leading mental health issues faced by infertile women are 1) anxiety 2) depression 3) anger 4) marital problems 5) sexual dysfunction 6) social isolation and 7) low self-esteem. Statistics have shown that amongst infertile couples, women often display higher distress than men, although when infertility is attributed to the male factor, the responses in males and females are the same.2 Furthermore, 15-54% of infertile couples experience depression, much higher than the average percentage of fertile couples experiencing depression.2 8-28% of infertile couples also experience severe anxiety.2 To complicate matters further, couples with a previous history of depression are susceptible to a two-fold increase in the likelihood of experiencing depression.2 This positive feedback loop is perhaps the biggest challenge women face; while previous mental health issues can alter ones ability to deal with the psychological stressors of infertility, the stressors associated with assisted conception often

exacerbate these very feelings of exasperation and anxiety.2 One Harvard Medical School study has even likened this phenomenon to the emotional distress experienced by heart disease and cancer patients.8 Accordingly, knowing when to stop treatment often proves the most difficult decision.8 Now, who exactly qualifies as infertile? According to nationally accepted criteria, women under the age of 33 unable to conceive within a year are considered infertile, as are women over the age of 34 unable to conceive within six months. Over the years, the number of women seeking treatment has risen, due to later childbearing, better treatment options, and increasing awareness of the many services available.2 However, one cannot help but wonder why the mental health implications associated with infertility have not yet been adequately addressed? As is the case with many other health conditions, medical diagnosis is often prioritized over mental health, while research funding for basic science is often easier to obtain than funding for psychological postulations. This coupled with the lack of understanding and empathy for the condition of women struggling with infertility has accordingly, resulted in a dearth of infertility related policy. That being said, some steps towards rectifying this problem have been taken. Current treatments for resulting mental health conditions include cognitive behavioral group psychotherapy, support groups, general stress relieving techniques, and potentially antidepressants. AcStanford Journal of Public Health

cording to the New York Times,8 in the past two years, nearly half of the 370 infertility centers approved by the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) have incorporated such services. However, despite the slight progress that has been made, one cannot help but wonderwhy hasnt more been accomplished? The answer to this question is undoubtedly quite complex, however, a good place to start is first recognizing that balancing the interests of the many stakeholders involved is quite challenging. Although the Obama Administration has largely been preoccupied with the push to address more controversial issues in womens health such as abortion, contraception, and health care coverage of these procedures, its point of view (or lack-thereof) is absolutely critical to influencing the policy-field and affecting change. The DHHS and its agencies are also integral, particularly in implementing such policy change. At the other end of the spectrum lies State Legislatures and their constituents, running the gamut from health care providers to private and public hospitals, to special interest groups, to national associations, and finally, to individual voters, particularly infertile women. Balancing these various interests is undoubtedly difficult, reducing the likelihood of passing infertility legislation dramatically. In fact, in the last 10 years, Congress has completely failed to pass infertility legislation on a national scale. What bills have even been proposed in the first place? Two major pieces of legislation in particular that Volume 3 Issue 1 Winter 2013

have repeatedly surfaced: 1) the Family Building Act (2009, 2007, 2005, 2003) requiring all health care plans to provide benefits for treatment of infertility and 2) the Medicare Infertility Coverage Act (2005, 2003) amending Medicare to cover infertility treatments for individuals entitled by reason of disability. Other proposed bills have also discussed research on and coverage of cancer-related infertility, a tax break for qualified infertility treatment expenses, and the creation of an Interagency Task Force. However, not a single one of these bills has ever reached the floors of Congress. At the state-level, fifteen states have now mandated coverage of infertility diagnosis and treatment,5 each outlining its own specific guidelines; however, many of these plans are still incomprehensive, with none in particular addressing mental health.6 The 1998 Supreme Court case Bragdon v. Abbott first fueled this discussion citing reproduction as a major life activity warranting protection under the Americans with Disabilities Act.1 However, while this historic precedent precluded employer discrimination on the basis of infertility, it did not resolve the question of coverage.3 Even more recent events such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) do not directly address issues of infertility, although prevention of unwanted pregnancies as well as maintenance of healthy pregnancies are well represented.9 The shortfalls in current policy are numerous. While, no sustainable, active effort has been made by national or state government, policy directly

targeting the mental health implications of infertility has not been proposed at all. Yet, a few strengths are to be noted; the possibility of financial burden has at least been broached. Furthermore, the infrastructure is already in placeBragdon v. Abbott and the PPACA provide room for more expansive financial coverage; they need only be clarified or amended. So how does one deal with such a problem? One can either 1) alleviate its effects or 2) eliminate the source itself. Below, I have outlined and provided an example of a policy proposal tackling the infertility challenge from both ends. Under each subtitle, I have provided in italics a simple summary of the requirements listed under each respective subsection: STATEMENT OF INTENT: Access to psychological resources must be made more accessible and treatment more affordable, thereby increasing access to care, the possibility of pregnancy, and the reduction of psychological stress. TITLE I: Increased Access to Psychological Services to Facilitate Coping SUBTITLE A: The DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services) should work with SART (Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology) leadership to develop a mandate urging the remaining half of SART-approved infertility centers to incorporate cognitive behavioral therapy and stress reduction services by the end of 2014. Services should be integrated with counseling on adoption and childfree living. Currently, approximately half of the SART-approved in-

28

Image courtesy of Microsoft

29