Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Consti Casespart2print

Transféré par

Carlo Alexir Lorica LolaCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Consti Casespart2print

Transféré par

Carlo Alexir Lorica LolaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

G.R. No. 159747 (Gregorio B. Honasan II vs.

The Panel of Investigating Prosecutors of the Department of Justice, CIDG-PNP-P/Director Eduardo Matillano, and Hon. Ombudsman Simeon V. Marcelo.) This refers to the (1) Urgent Clarification and Motion of our Resolution dated June 15, 2004 denying petitioner's motion to cite respondent Panel in contempt of court and the (2) Motion for Reconsideration as well as respondent DOJ Panel's comment thereto. We find that the motion for reconsideration was actually filed by registered mail on May 7, 2004 and therefore within the reglementary period of filing the same. Thus, the portion of our Resolution dated June 15, 2004 declaring our decision final and executory is set aside. However, a study of petitioner's motion for reconsideration shows that the arguments raised therein were already considered in arriving at our decision sought to be reconsidered and we find no cogent reason to reverse our earlier findings that respondent DOJ Panel has concurrent jurisdiction to conduct the preliminary investigation on the charge of coup d'etat filed against petitioner. Petitioner posits the view that we should not have refrained from ruling on the issue of whether or not the charge against petitioner is committed in relation to his office. We are not persuaded. The resolution of such issue should only be resolved after a hearing has been conducted by respondent Panel and petitioner has already presented his evidence to show that the crime charged was committed in relation to his office. We reiterate that we resolved not to dwell on said issue so as not to pre-empt the result of the investigation being conducted by the DOJ Panel as to the questions (1) whether or not probable cause exists to warrant the filing of the information against the petitioner and (2) to which court should the information be filed considering the presence of the other respondents in the subject complaint. Anent petitioner's allegations of marked bias and prejudice of the respondent DOJ Panel because of the utterances made by the President and other top officials of her administration prejudging his guilt, the Court finds the same to be lacking in factual foundation. The DOJ Panel is composed of lawyers whose sworn duty is to investigate the commission and prosecution of criminal cases and who are expected to fulfill their assigned role in the administration of justice with fairness. Whatever remarks made in connection with the charge do not by itself prove that it would influence the minds of the members of the Panel on what their judgment would be after the whole evidence of petitioner's case shall have been examined and evaluated by them. Allegation of bias is not enough absent any viable proof thereof since it is not for this Court to assume in advance that the DOJ Panel would fail to discharge its manifest duty in the conduct of the preliminary investigation. We have had occasion to rule in a criminal case that a charge made before trial that a party will not be given a fair, impartial and just hearing is premature.1 Prejudice is not to be presumed especially if weighed against a judge's legal obligation under his oath to administer justice without respect to person and do equal right to the poor and the rich.2 We likewise find unpersuasive petitioner's claim of alleged prejudicial acts committed by respondent DOJ Panel in the initial stages of the conduct of the preliminary investigation. WHEREFORE, acting on the motion for clarification, our Resolution dated June 15, 2004 is hereby amended only to the effect that petitioner's motion for reconsideration is timely filed. However, petitioner's motion for reconsideration is DENIED for lack of merit. (Same voting) REP. VIRGILIO P. ROBLES, petitioner, vs. HON. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL and ROMEO L. SANTOS, respondents. Virgilio P. Robles for and in his own behalf. Brillantes, Nachura, Navarro & Arcilla Law Offices for private respondent.

On January 5, 1988, Santos filed an election protest with respondent HRET. He alleged, among others, that the elections in the 1st District of Caloocan City held last May 11, 1987 were characterized by the commission of electoral frauds and irregularities in various forms, on the day of elections, during the counting of votes and during the canvassing of the election returns. He likewise prayed for the recounting of the genuine ballots in all the 320 contested precincts (pp. 1620, Rollo). On January 14, 1988, petitioner filed his Answer (pp. 22-26, Rollo) to the protest. He alleged as among his affirmative defenses, the lack of residence of protestant and the late filing of his protest. On August 15, 1988, respondent HRET issued an order setting the commencement of the revision of contested ballots on September 1, 1988 and directed protestant Santos to identify 25% of the total contested precincts which he desires to be revised first in accordance with Section 18 of the Rules of the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (pp. 76-77, Rollo). On September 7, 1988, the revision of the ballots for 75 precincts, representing the initial 25% of all the contested precincts, was terminated. On September 8, 1988, Robles filed an Urgent Motion to Suspend Revision and on September 12, 1988, Santos filed a Motion to Withdraw Protest on the unrevised precincts (pp. 78-80, Rollo). No action on Robles' motion to suspend revision and Santos' motion to withdraw protest on unrevised precincts were yet taken by respondent HRET when on September 14,1988, Santos filed an Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest (pp. 81-85, Rollo). On September 19, 1988, Robles opposed Santos' motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest in an Urgent Motion to Cancel Continuation of Revision with Opposition to Motion to Recall Withdrawal (pp. 86-91, Rollo). On the same day, respondent HRET issued a resolution which, among others, granted Santos' urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest. The said resolution states: House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal Case No. 43 (Romeo L. Santos vs. Virgilio P. Robles). Three pleadings are submitted for consideration by the Tribunal: (a) Protestee's "Urgent Motion to Suspend Revision," dated September 8, 1988; (b) Protestant's "Motion to Withdraw Protest on Unrevised Precincts and Motion to Set Case for Hearing," dated September 12, 1988; and (c) Protestant's Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest, dated September 14, 1988. Upon the filing of Protestant's Motion to Withdraw Protest, the revision of ballots was stopped and such revision remains suspended until now. In view of such suspension, there is no need to act on Protestee's Motion. The "Motion to Withdraw Protest," has been withdrawn by Protestant's later motion, and therefore need not be acted upon. WHEREFORE, Protestee's "Urgent Motion to Suspend Revision" and Protestant's 'Motion to Withdraw Protest' are NOTED. The 'Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest' is GRANTED. The Secretary of the Tribunal is directed to schedule the resumption of the revision on September 26, 1988 and to send out the necessary notices for this purpose. (p. 84, Rollo). On September 20,1988, Robles filed an Urgent Motion and Manifestation praying that his Urgent Motion to Cancel Revision with Opposition to Motion to Recall dated September 19, 1988 be treated as a Motion for Reconsideration of the HRET resolution of September 19, 1988 (pp. 92-94, Rollo). On September 22, 1988, respondent HRET directed Santos to comment on Robles' "Urgent Motion to Cancel Continuation of Revision with Opposition to Motion to Recall Withdrawal" and ordered the suspension of the resumption of revision scheduled for September 26, 1988. On January 26,1989, the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal denied Robles' Motion for Reconsideration (pp. 109-111, Rollo). Hence, the instant petition was filed on February 1, 1989 (pp. 1-14, Rollo). On February 2, 1989, We required the respondent to comment within ten (10) days from notice of the petition (p. 118, Rollo). On February 9, 1989, petitioner Robles filed an Urgent Motion Reiterating Prayer for Injunction or Restraining Order (pp. 119-120, Rollo) which We Noted on February 16, 1989. Petitioner's Motion for Leave to File Reply to Comment was granted in the same resolution of February 16,1989. On February 22, 1989, petitioner filed a Supplemental Petition (p. 129, Rollo), this time questioning respondent HRET's February 16, 1989 resolution denying petitioner's motion to defer or reset revision until this Court has finally disposed of the instant petition and declaring that a partial determination pursuant to Section 18 of the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal Rules was had with

MEDIALDEA, J.: This is a petition for certiorari with prayer for a temporary restraining order assailing the resolutions of the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (HRET): 1) dated September 19, 1988 granting herein private respondent's Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest, and 2) dated January 26, 1989, denying petitioner's Motion for Reconsideration. Petitioner Virgilio Robles and private respondent Romeo Santos were candidates for the position of Congressman of the 1st district of Caloocan City in the last May 11, 1987 congressional elections. Petitioner Robles was proclaimed the winner on December 23, 1987.

private respondent Santos making a recovery of 267 votes (see Annex "C" of Supplemental Petition, p. 138, Rollo). It is petitioner's main contention in this petition that when private respondent Santos filed the Motion to Withdraw Protest on Unrevised Precincts and Motion to Set Case for Hearing dated September 12, 1988, respondent HRET lost its jurisdiction over the case, hence, when respondent HRET subsequently ordered the revision of the unrevised protested ballots, notwithstanding the withdrawal of the protest, it acted without jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion. We do not agree with petitioner. It is noted that upon Santos' filing of his Motion to Withdraw Protest on Unrevised Precincts on September 12, 1988, no action thereon was taken by respondent HRET Contrary to petitioner's claim that the motion to withdraw was favorably acted upon, the records show that it was only on September 19, 1988 when respondent HRET resolved said motion together with two other motions. The questioned resolution of September 19, 1988 resolved three (3) motions, namely: a) Protestee's Urgent Motion to Suspend Revision dated September 8, 1988; b) Protestant's Motion to Withdraw Protest on Unrevised Precincts and Motion to Set Case for Hearing dated September 12, 1988; and c) Protestant's "Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest," dated September 14, 1988. The resolution resolved the three (3) motions as follows: xxx xxx xxx WHEREFORE, Protestee's "Urgent Motion to Suspend Revision" and Protestant's 'Motion to Withdraw Protest' are NOTED. The "Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest" is GRANTED. xxx xxx xxx The mere filing of the motion to withdraw protest on the remaining uncontested precincts, without any action on the part of respondent tribunal, does not by itself divest the tribunal of its jurisdiction over the case. Jurisdiction, once acquired, is not lost upon the instance of the parties but continues until the case is terminated (Jimenez v. Nazareno, G.R. No. L-37933, April 15, 1988, 160 SCRA 1). We agree with respondent House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal when it held: We cannot agree with Protestee's contention that Protestant's "Motion to Withdraw Protest on Unrevised Precincts" effectively withdrew the precincts referred to therein from the protest even before the Tribunal has acted thereon. Certainly, the Tribunal retains the authority to grant or deny the Motion, and the withdrawal becomes effective only when the Motion is granted. To hold otherwise would permit a party to deprive the Tribunal of jurisdiction already acquired. We hold therefore that this Tribunal retains the power and the authority to grant or deny Protestant's Motion to Withdraw, if only to insure that the Tribunal retains sufficient authority to see to it that the will of the electorate is ascertained. Since Protestant's "Motion to Withdraw Protest on the Unrevised Precincts" had not been acted upon by this Tribunal before it was recalled by the Protestant, it did not have the effect of removing the precincts covered thereby from the protest. If these precincts were not withdrawn from the protest, then the granting of Protestant's "Urgent Motion to Recall and Disregard Withdrawal of Protest" did not amount to allowing the refiling of protest beyond the reglementary period. Where the court has jurisdiction over the subject matter, its orders upon all questions pertaining to the cause are orders within its jurisdiction, and however erroneous they may be, they cannot be corrected by certiorari (Santos v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 56614, July 28,1987,152 SCRA 378; Paramount Insurance Corp. v. Luna, G.R. No. 61404, March 16,1987,148 SCRA 564). This rule more appropriately applies to respondent HRET whose independence as a constitutional body has time and again been upheld by Us in many cases. As explained in the case of Lazatin v. The House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal and Timbol, G.R. No. 84297, December 8, 1988, thus: The use of the word "sole" emphasizes the exclusive character of the jurisdiction conferred [Angara v. Electoral Commission, supra ,at 162]. The exercise of the Power by the Electoral Commission under the 1935 Constitution has been described as "intended to be complete and unimpaired as if it had remained originally in the legislature" [Id. at 175]. Earlier, this grant of power to the legislature was characterized by Justice Malcolm as "full, clear and complete" [Veloso v. Board of Canvassers of Leyte and Samar, 39 Phil. 886 (1919)]. Under the amended 1935 Constitution, the power was unqualifiedly reposed upon the Electoral Tribunal [Suanes v. Chief Accountant of the Senate, 81 Phil. 818 (1948)] and it remained as full, clear and complete as that previously granted the legislature and the Electoral Commission [ Lachica v. Yap, G.R. No. L-25379, September 25, 1968, 25 SCRA 140]. The same may be said with regard to the jurisdiction of the Electoral Tribunals

under the 1987 Constitution. Thus, "judicial review of decisions or final resolutions of the House Electoral Tribunal is (thus) possible only in the exercise of this Court's so-called extraordinary jurisdiction, . . . upon a determination that the tribunal's decision or resolution was rendered without or in excess of its jurisdiction, or with grave abuse of discretion or, paraphrasing Morrera, upon a clear showing of such arbitrary and improvident use by the Tribunal of its power as constitutes a denial of due process of law, or upon a demonstration of a very clear unmitigated ERROR, manifestly constituting such a GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION that there has to be a remedy for such abuse. In the absence of any clear showing of abuse of discretion on the part of respondent tribunal in promulgating the assailed resolutions, a writ of certiorari will not issue. Further, petitioner's objections to the resolutions issued by respondent tribunal center mainly on procedural technicalities, i.e., that the motion to withdraw, in effect, divested the HRET of jurisdiction over the electoral protest. This argument aside from being irrelevant and baseless, overlooks the essence of a public office as a public trust. The right to hold an elective office is rooted on electoral mandate, not perceived entitlement to the office. This is the reason why an electoral tribunal has been set up in order that any doubt as to right/mandate to a public office may be fully resolved vis-a-vis the popular/public will. To this end, it is important that the tribunal be allowed to perform its functions as a constitutional body, unhampered by technicalities or procedural play of words. The case of Dimaporo v. Estipona (G.R. No. L-17358, May 30, 1961, 2 SCRA 282) relied upon by petitioner does not help to bolster his case because the facts attendant therein are different from the case at bar. In the said case, the motion to withdraw was favorably acted upon before the resolution thereon was questioned. As regards petitioner's Supplemental Petition questioning respondent tribunal's resolution denying his motion to defer or reset revision of the remaining seventyfive (75) per cent of the contested precincts, the same has become academic in view of the fact that the revision was resumed on February 20, 1989 and was terminated on March 2, 1989 (Private Respondent's Memorandum, p. 208, Rollo). This fact was not rebutted by petitioner. The allegation of petitioner that he was deprived of due process when respondent tribunal rendered a partial determination pursuant to Section 18 of the HRET rules and found that Santos made a recovery of 267 votes after the revision of the first twenty-five per cent of the contested precincts has likewise, no basis. The partial determination was arrived at only by a simple addition of the votes adjudicated to each party in the revision of which both parties were properly represented. It would not be amiss to state at this point that "an election protest is impressed with public interest in the sense that the public is interested in knowing what happened in the elections" (Dimaporo v. Estipona, supra.), for this reason, private interests must yield to what is for the common good. ACCORDINGLY, finding no grave abuse of discretion on the part of respondent House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal in issuing the assailed resolutions, the instant petition is DISMISSED.. CARMELO F. LAZATIN, petitioner, vs. THE HOUSE ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL and LORENZO G. TIMBOL, respondents. Angara, Abello, Concepcion, Regala & Cruz for petitioner. The Solicitor General for respondents.

CORTES, J.: Petitioner and private respondent were among the candidates for Representative of the first district of Pampanga during the elections of May 11, 1987. During the canvassing of the votes, private respondent objected to the inclusion of certain election returns. But since the Municipal Board of Canvassers did not rule on his objections, he brought his case to the Commission on Elections. On May 19, 1987, the COMELEC ordered the Provincial Board of Canvassers to suspend the proclamation of the winning candidate for the first district of Pampanga. However, on May 26, 1987, the COMELEC ordered the Provincial Board of Canvassers to proceed with the canvassing of votes and to proclaim the winner. On May 27, 1987, petitioner was proclaimed as Congressman-elect. Private respondent thus filed in the COMELEC a petition to declare petitioners proclamation void ab initio. Later, private respondent also filed a petition to prohibit petitioner from assuming office. The COMELEC failed to act on the second petition so petitioner was able to assume office on June 30, 1987. On September 15, 1987, the COMELEC declared petitioner's proclamation void ab initio. Petitioner challenged the COMELEC resolution before this Court in a petition entitled "Carmelo F. Lazatin v. The Commission on Elections, Francisco R. Buan, Jr. and Lorenzo G. Timbol," docketed as G.R. No. 80007. In a decision promulgated on January 25, 1988, the Court set aside the COMELEC's

revocation of petitioner's proclamation. On February 8, 1988, private respondent filed in the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (hereinafter referred to as HRET an election protest, docketed as Case No. 46. Petitioner moved to dismiss private respondent's protest on the ground that it had been filed late, citing Sec. 250 of the Omnibus Election Code (B.P. Blg. 881). However, the HRET filed that the protest had been filed on time in accordance with Sec. 9 of the HRET Rules. Petitioner's motion for reconsideration was also denied. Hence, petitioner has come to this Court, challenging the jurisdiction of the HRET over the protest filed by private respondent. A. The Main Case This special civil action for certiorari and prohibition with prayer for the issuance of a writ of preliminary injunction and/or restraining order seeks the annulment and setting aside of (1) the resolution of the HRET, dated May 2, 1988, in Case No. 46, holding that the protest filed by private respondent had been filed on time, and (2) its July 29, 1988 resolution denying the motion for reconsideration. Without giving due course to the petition, the Court required the respondents to comment on the petition. The Solicitor General filed a comment in behalf of the HRET while the private respondent filed his comment with a motion to admit counter/cross petition and the petitioner filed his consolidated reply. Thereafter, the Court resolved to give due course to the petition, taking the comments filed as the answers to the petition, and considered the case submitted for decision. Resolution of the instant controversy hinges on which provision governs the period for filing protests in the HRET. Should Sec. 250 of the Omnibus Election Code be held applicable, private respondent's election protest would have been filed out of time. On the other hand, if Sec. 9 of the HRET Rules is applicable, the filing of the protest would be timely. Succinctly stated, the basic issue is whether or not private respondent's protest had been seasonably filed. To support his contention that private respondent's protest had been filed out of time and, therefore, the HRET did not acquire jurisdiction over it, petitioner relies on Sec. 250 of the Omnibus Election Code, which provides: Sec. 250. Election contests for Batasang Pambansa, regional, provincial and city offices. A sworn petition contesting the election of any Member of the Batasang Pambansa or any regional, provincial or city official shall be filed with the Commission by any candidate who has duly filed a certificate of candidacy and has been voted for the same office, within ten days after the proclamation of the results of the election. [Emphasis supplied.] Petitioner argues that even assuming that the period to file an election protest was suspended by the pendency of the petition to annul his proclamation, the petition was filed out of time, considering that he was proclaimed on May 27, 1987 and therefore private respondent had only until June 6, 1987 to file a protest; that private respondent filed a petition to annul the proclamation on May 28, 1987 and the period was suspended and began to run again on January 28, 1988 when private respondent was served with a copy of the decision of the Court in G.R, No. 80007; that private respondent therefore only had nine (9) days left or until February 6, 1988 within which to file his protest; but that private respondent filed his protest with the HRET only on February 8, 1988. On the other hand, in finding that the protest was flied on time, the HRET relied on Sec. 9 of its Rules, to wit: Election contests arising from the 1987 Congressional elections shall be filed with the Office of the Secretary of the Tribunal or mailed at the post office as registered matter addressed to the Secretary of the Tribunal, together with twelve (12) legible copies thereof plus one (1) copy for each protestee,within fifteen (15) days from the effectivity of these Rules on November 22, 1987 where the proclamation has been made prior to the effectivity of these Rules, otherwise, the same may be filed within fifteen (15) days from the date of the proclamation. Election contests arising from the 1987 Congressional elections filed with the Secretary of the House of Representatives and transmitted by him to the Chairman of the Tribunal shall be deemed filed with the tribunal as of the date of effectivity of these Rules, subject to payment of filing fees as prescribed in Section 15 hereof. [Emphasis supplied.] Thus, ruled the HRET: On the basis of the foregoing Rule, the protest should have been filed within fifteen (15) days from November 22, 1987, or not later than December 7, 1987. However, on September 15, 1987, the COMELEC acting upon a petition filed by the Protestant (private respondent herein), promulgated a Resolution declaring the proclamation void ab initio. This resolution had the effect of nullifying the proclamation, and such proclamation was not reinstated until Protestant

received a copy of the Supreme Court's decision annulling the COMELEC Resolution on January 28, 1988. For all intents and purposes, therefore, Protestee's (petitioner herein) proclamation became effective only on January 28, 1988, and the fifteen-day period for Protestant to file his protest must be reckoned from that date. Protestant filed his protest on February 8, 1988, or eleven (11) days after January 28. The protest, therefore, was filed well within the reglementary period provided by the Rules of this Tribunal. (Rollo, p. 129.] The Court is of the view that the protest had been filed on time and, hence, the HRET acquired jurisdiction over it. Petitioner's reliance on Sec. 250 of the Omnibus Election Code is misplaced. Sec. 250 is couched in unambiguous terms and needs no interpretation. It applies only to petitions filed before the COMELEC contesting the election ofany Member of the Batasang Pambansa, or any regional, provincial or city official. Furthermore, Sec. 250 should be read together with Sec. 249 of the same code which provides that the COMELEC "shall be the sole judge of all contests relating to the elections, returns and qualifications of all Members of the Batasang Pambansa, elective regional, provincial and city officials," reiterating Art. XII-C, Sec. 2(2) of the 1973 Constitution. It must be emphasized that under the 1973 Constitution there was no provision for an Electoral Tribunal, the jurisdiction over election contests involving Members of the Batasang Pambansa having been vested in the COMELEC. That Sec. 250 of the Omnibus Election Code, as far as contests regarding the election, returns and qualifications of Members of the Batasang Pambansa is concerned, had ceased to be effective under the 1987 Constitution is readily apparent. First, the Batasang Pambansa has already been abolished and the legislative power is now vested in a bicameral Congress. Second, the Constitution vests exclusive jurisdiction over all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the Members of the Senate and the House of Representatives in the respective Electoral Tribunals [Art. VI, Sec. 171. The exclusive original jurisdiction of the COMELEC is limited by constitutional fiat to election contests pertaining to election regional, provincial and city offices and its appellate jurisdiction to those involving municipal and barangay offices [Art. IX-C, Sec. 2(2)]. Petitioner makes much of the fact that the provisions of the Omnibus Election Code on the conduct of the election were generally made applicable to the congressional elections of May 11, 1987. It must be emphasized, however, that such does not necessarily imply the application of all the provisions of said code to each and every aspect of that particular electoral exercise, as petitioner contends. On the contrary, the Omnibus Election Code was only one of several laws governing said elections. * An examination of the Omnibus Election Code and the executive orders specifically applicable to the May 11, 1987 congressional elections reveals that there is no provision for the period within which to file election protests in the respective Electoral Tribunals. Thus, the question may well be asked whether the rules governing the exercise of the Tribunals' constitutional functions may be prescribed by statute. The Court is of the considered view that it may not. The power of the HRET, as the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the Members of the House of Representatives, to promulgate rules and regulations relative to matters within its jurisdiction, including the period for filing election protests before it, is beyond dispute. Its rule-making power necessarily flows from the general power granted it by the Constitution. This is the import of the ruling in the landmark case of Angara v. Electoral Commission [63 Phil. 139 (1936)], where the Court, speaking through Justice Laurel, declared in no uncertain terms: ... [The creation of the Electoral Commission carried with it ex necessitate rei the power regulative in character to limit the time within which protests entrusted to its cognizance should be filed. It is a settled rule of construction that where a general power is conferred or duly enjoined, every particular power necessary for the exercise of the one or the performance of the other is also conferred (Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, eighth ed., vol. 1, pp. 138, 139). In the absence of any further constitutional provision relating to the procedure to be followed in filing protests before the Electoral Commission, therefore, the incidental power to promulgate such rules necessary for the proper exercise of its exclusive power to judge all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of members of the National Assembly, must be deemed by necessary implication to have been lodged also in the Electoral Commission. [At p. 177; emphasis supplied.] A short review of our constitutional history reveals that, except under the 1973 Constitution, the power to judge all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the members of the legislative branch has been exclusively granted either to the legislative body itself [i.e., the Philippine Assembly under the Philippine Bill of 1902 and the Senate and the House of Representatives under the Philippine

Autonomy Act (Jones Law)] or to an independent, impartial and non-partisan body attached to the legislature [i.e., the Electoral Commission under the 1935 Constitution and the Electoral Tribunals under the amended 1935 and the 1987 Constitutions]. Except under the 1973 Constitution, the power granted is that of being the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the members of the legislative body. Article VI of the 1987 Constitution states it in this wise: See. 17. The Senate and the House of Representatives shall each have an Electoral Tribunal which shall be the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns, and qualifications of their respective Members. Each Electoral tribunal shall be composed of nine Members, three of whom shall be Justices of the Supreme Court to be designated by the Chief Justice, and the remaining six shall be Members of the Senate or the House of Representatives, as the case may be, who shall be chosen on the basis of proportional representation from the political parties and the parties or organizations registered under the party-list system represented therein. The senior Justice in the Electoral Tribunal shall be its Chairman. The use of the word "sole" emphasizes the exclusive character of the jurisdiction conferred [Angara v. Electoral Commission, supra, at 1621. The exercise of the power by the Electoral Commission under the 1935 Constitution has been described as "intended to be as complete and unimpaired as if it had remained originally in the legislature" [Id. at 175]. Earlier, this grant of power to the legislature was characterized by Justice Malcolm as "full, clear and complete" [Veloso v. Board of Canvassers of Leyte and Samar, 39 Phil. 886 (1919)]. Under the amended 1935 Constitution, the power was unqualifiedly reposed upon the Electoral Tribunal Suanes v. Chief Accountant of the Senate, 81 Phil. 818 (1948)] and it remained as full, clear and complete as that previously granted the legislature and the Electoral Commission Lachica v. Yap, G.R. No. L25379, September 25, 1968, 25 SCRA 1401. The same may be said with regard to the jurisdiction of the Electoral Tribunals under the 1987 Constitution. The 1935 and 1987 Constitutions, which separate and distinctly apportion the powers of the three branches of government, lodge the power to judge contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of members of the legislature in an independent, impartial and non-partisan body attached to the legislature and specially created for that singular purpose (i.e., the Electoral Commission and the Electoral Tribunals) [see Suanes v. Chief Accountant of the Senate, supra]. It was only under the 1973 Constitution where the delineation between the powers of the Executive and the Legislature was blurred by constitutional experimentation that the jurisdiction over election contests involving members of the Legislature was vested in the COMELEC, an agency with general jurisdiction over the conduct of elections for all elective national and local officials. That the framers of the 1987 Constitution intended to restore fully to the Electoral Tribunals exclusive jurisdiction over all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of its Members, consonant with the return to the separation of powers of the three branches of government under the presidential system, is too evident to escape attention. The new Constitution has substantially retained the COMELEC's purely administrative powers, namely, the exclusive authority to enforce and administer all laws and regulations relative to the conduct of an election, plebiscite, initiative, referendum, and recall; to decide, except those involving the right to vote, all questions affecting elections; to deputize law enforcement agencies and government instrumentalities for election purposes; to register political parties and accredit citizens' arms; to file in court petitions for inclusion and exclusion of voters and prosecute, where appropriate, violations of election laws [Art. IX(C), Sec. 2(1), (3)-(6)], as well as its rule-making power. In this sense, and with regard to these areas of election law, the provisions of the Omnibus Election Code are fully applicable, except where specific legislation provides otherwise. But the same cannot be said with regard to the jurisdiction of the COMELEC to hear and decide election contests. This has been trimmed down under the 1987 Constitution. Whereas the 1973 Constitution vested the COMELEC with jurisdiction to be the sole judge of all contests relating to the elections, returns and qualifications of all Members of the Batasang Pambansa and elective provincial and city officials [Art. XII(C), Sec. 2(2)], the 1987 Constitution, while lodging in the COMELEC exclusive original jurisdiction over all contests relating to the elections, returns and qualifications of all elective regional, provincial and city officials and appellate jurisdiction over contests relating to the election of municipal and barangay officials [Art. IX(C), Sec. 2(2)]. expressly makes the Electoral Tribunals of the Senate and the House of Representatives the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of their respective Members [Art. VI, Sec. 17]. The inescapable conclusion from the foregoing is that it is well within the power of the HRET to prescribe the period within which protests may be filed before it. This is founded not only on historical precedents and jurisprudence but, more importantly, on the clear language of the Constitution itself. Consequently, private respondent's election protest having been filed within the period prescribed by the HRET, the latter cannot be charged with lack of jurisdiction to hear the case.

B. Private-Respondent's Counter/Cross Petition Private respondent in HRET Case No. 46 prayed for the issuance of a temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction to enjoin petitioner herein from discharging his functions and duties as the Representative of the first district of Pampanga during the pendency of the protest. However, on May 5, 1988, the HRET resolved to defer action on said prayer after finding that the grounds therefor did not appear to be indubitable. Private respondent moved for reconsideration, but this was denied by the HRET on May 30, 1988. Thus, private respondent now seeks to have the Court annul and set aside these two resolutions and to issue a temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction on the premise that the grounds therefor are too evident to be doubted. The relief prayed for in private respondent's counter/cross petition is not forthcoming. The matter of whether or not to issue a restraining order or a writ of preliminary injunction during the pendency of a protest lies within the sound discretion of the HRET as sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the Members of the House of Representatives. Necessarily, the determination of whether or not there are indubitable grounds to support the prayer for the aforementioned ancilliary remedies also lies within the HRETs sound judgment. Thus, in G.R. No. 80007, where the Court declined to take cognizance of the private respondent's electoral protest, this Court said: The alleged invalidity of the proclamation (which had been previously ordered by the COMELEC itself) despite alleged irregularities in connection therewith, and despite the pendency of the protests of the rival candidates, is a matter that is also addressed, considering the premises, to the sound judgment of the Electoral Tribunal. Moreover, private respondent's attempt to have the Court set aside the HRET's resolution to defer action on his prayer for provisional relief is undeniably premature, considering that the HRET had not yet taken any final action with regard to his prayer. Hence, there is actually nothing to review or and and set aside. But then again, so long as the Constitution grants the HRET the power to be the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of Members of the House of Representatives, any final action taken by the HRET on a matter within its jurisdiction shall, as a rule, not be reviewed by this Court. As stated earlier, the power granted to the Electoral Tribunal is full, clear and complete and "excludes the exercise of any authority on the part of this Court that would in any wise restrict or curtail it or even affect the same." (Lachica v. Yap, supra, at 143.] As early as 1938 in Morrero v. Bocar (66 Phil. 429, 431 (1938)), the Court declared that '[the judgment rendered by the [Electoral] Commission in the exercise of such an acknowledged power is beyond judicial interference, except, in any event, upon a clear showing of such arbitrary and improvident use of the power as will constitute a denial of due process of law." Under the 1987 Constitution, the scope of the Court's authority is made explicit. The power granted to the Court includes the duty "to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government (Art. VIII, Sec. 11. Thus, only where such grave abuse of discretion is clearly shown shall the Court interfere with the HRET's judgment. In the instant case, there is no occasion for the exercise of the Court's collective power, since no grave abuse of discretion that would amount to lack or excess of jurisdiction and would warrant the issuance of the writs prayed for has been clearly shown. WHEREFORE, the instant Petition is hereby DISMISSED. Private respondent's Counter/Cross Petition is likewise DISMISSED. ROSETTE YNIGUEZ LERIAS, petitioner, vs. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL and ROGER G. MERCADO, respondent. Lino M. Patajo for petitioner. Brillantes, Nachua, Navarro & Arcilla Law Offices for private respondent.

PARAS, J.:p Politicians who are members of electoral tribunals, must think and act like judges, accordingly, they must resolve election controversies with judicial, not political, integrity. The independence of the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal, (HRET, for brevity) as a constitutional body has time and again been upheld by this Court in many cases. (Lazatin v. House Electoral Tribunal, 168 SCRA 391; Robles v. House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal, 181 SCRA 780). The power of the HRET, as the "sole judge" of all contests relating to the election returns and qualifications of its members is beyond dispute. (Art. VI, Sec. 17 of the 1987 Constitution) Thus, judicial review of decisions or final resolutions of the HRET is possible only in the exercise of this Court's so-called "extra-ordinary jurisdiction" upon a determination that the tribunal's decision or resolution was rendered without or in excess of its jurisdiction

or with grave abuse of discretion or upon a clear showing of such arbitrary and improvident use by the Tribunal of its power as constitutes a denial of due process of law, or upon a demonstration of a very clear unmitigated error, manifestly constituting such a grave abuse of discretion that there has to be a remedy for such abuse. (Morrero v. Bocar, 66 Phil. 429, 431; Lazatin v. House Electoral Tribunal, supra; Robles v. HRET, supra) Then only where such grave abuse of discretion is clearly shown that the Court interferes with the HRET's judgment or decision. Accordingly, it is in this light that We shall proceed to examine the contentions of the parties in this case. Petitioner Rosette Y. Lerias filed her certificate of candidacy as the official candidate of the UPP-KBL for the position of Representative for the lone district of Southern Leyte in the May 11, 1987 elections. In her certificate of candidacy she gave her full name as "Rosette Ynigues Lerias". Her maiden name is Rosette Ynigues. Respondent Roger G. Mercado was the administration candidate for the same position. During the canvass of votes for the congressional candidates by the Provincial Board of Canvassers of Southern Leyte, it appeared that, excluding the certificate of canvass from the Municipality of Libagon which had been questioned by Mercado on the ground that allegedly it had been tampered with, the candidates who received the two (2) highest number of votes were Roger G. Mercado with 34,442 votes and Rosette Y. Lerias with 34,128 votes, respectively. In the provincial board's copy of the certificate of canvass for the municipality of Libagon, Lerias received 1,811 votes while Mercado received 1,351. Thus, if said copy would be the one to be included in the canvass, Lerias would have received 35,939 votes as against Mercado's 35,793 votes, giving Lerias a winning margin of 146 votes. But, the provincial board of canvassers ruled that their copy of the certificate of canvass contained erasures, alterations and superimpositions and therefore, cannot be used as basis of the canvass. The provincial board of canvassers rejected the explanation of the members of the municipal board of canvassers of Libagon that said corrections were made to correct honest clerical mistakes which did not affect the integrity of the certificate and said corrections were made in the presence of the watchers of all the nine (9) candidates for the position, including those of Mercado who offered no objection. Lerias appealed the ruling of the provincial board of canvassers to the Comelec praying that the Commission order the provincial board of canvassers to use their copy of the certificate of canvass for Libagon. At the scheduled hearing on June 5, 1987, Atty. Valeriano Tumol, then counsel for Lerias, agreed to use the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass provided that it be found to be authentic and genuine. A similar reservation was made by counsel for Mercado. The Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass was produced and when opened it showed that Lerias received only 1,411 votes in Libagon because in Precincts 6, 10, 18 and 19 she received in each of the said precincts 100 votes less than what she received as shown in the provincial board of canvasser's copy of the certificate of canvass. The alleged discrepancy is as follows:

There being no action taken by the Comelec on the said motion and since the term of office of the members of the House of Representatives would commence on June 30, 1987, Lerias filed on June 30, 1987 before this Court a petition (G.R. No. 78833) for the annulment of the Comelec resolution of June 6, 1987 and the proclamation of Mercado. Meanwhile, in SPC-87-488, the Comelec en banc required Mercado to file an answer. Instead of filing an answer, however, Mercado filed a motion to dismiss on the grounds that (a) the resolution dated June 6, 1987 had already become final because the motion for reconsideration filed by Lerias was ex-parte and did not stop the running of the period to appeal therefrom and (b) since Lerias filed with the Supreme Court a petition for the annulment of the Comelec's June 6, 1987 resolution and the subsequent proclamation of Mercado, she had abandoned her previous petition with the Comelec. At the scheduled hearing on June 16, 1987 of SPC-87-488, the members of the municipal board of canvassers of Libagon and the school teachers who served as inspectors of Precincts 6, 10, 18 and 19 were present and manifested that they were ready to testify and affirm that the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass was not authentic for it did not correctly state the number of votes received by the parties since Lerias actually obtained 1,811 votes in Libagon, not 1,411 votes. The Comelec did not want to hear the case on the merits opting instead to merely hear Mercado's motion to dismiss. The said witnesses were not given the chance to testify. On June 17, 1987, the Comelec resolved to dismiss SPC-87-488 because the petitioner had filed a case with the Supreme Court and had, therefore, abandoned her case with the Comelec. On July 22, 1987 Lerias filed with this Court a second petition to set aside not only the Comelec's resolution of July 6, 1987 but also the resolution of July 17, 1987. The petition was heard on oral argument and on September 10, 1987, this Court dismissed the petition because (a) the Comelec resolution of June 6, 1987 and the proclamation of Mercado had already become executory inasmuch as five days had elapsed from receipt of a copy of said resolution by petitioner and no restraining order had been issued by the Court citing Sec. 246 of the Omnibus Election Code, and (b) Lerias thru counsel had agreed before the Comelec (Second Division) during the hearing therein on June 5, 1987 to use the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass. Lerias filed a motion for reconsideration but the same was denied. Hence, on October 1, 1987, she filed an election protest with respondent HRET. In her protest, Lerias contested the results of the election in Precinct Nos. 6, 10, 18 & 19 of Libagon asserting that the total votes credited to her in the said four precincts (1,411 votes) were less than or short by 400 votes from that actually obtained by her (1,811 votes) and if the provincial board of canvassers' copy of the certificate of canvass for Libagon were to be used as basis of the canvass instead of the Comelec copy, she would have garnered 35,930 votes as against Mercado's 35,793 votes or a winning margin of 146 votes. Thus, Lerias prayed that (a) precautionary measures be undertaken for the safekeeping and custody of the ballot boxes and election documents used in the protested precincts and that they be brought to the Tribunal to prevent tampering and to protect their integrity; (b) a recount of the votes cast in said precincts be immediately ordered; and (c) the proclamation of Mercado be set aside and that she be declared the duly elected Representative for the lone district of Southern Leyte. She further prayed that Mercado be ordered to pay damages, attorney's fees and costs. Mercado filed his Answer with Counter-Protest, denying the material allegations of the protest and counter-protesting the results of the elections in 377 precincts. He alleged that the votes cast for him were (a) intentionally misread in favor of Lerias; (b) not counted or tallied, and/or counted or tallied in favor of Lerias; (c) considered marked or were intentionally marked and; (d) tampered and changed. The counterprotest also charged that blank spaces in the ballots were filled with Lerias' name; that various ballots for Lerias, pasted with stickers, were considered valid and counted for Lerias; that votes in the election returns were tampered with and altered in favor of Lerias, and that terrorism and massive vote-buying were employed by her. The initial hearing was scheduled for August 22, 1988, but on March 7, 1988 unidentified uniformed armed men raided the municipal building of Libagon and stole the ballot boxes for the 20 precincts of Libagon stored in the office of the municipal treasurer. Fortunately, these armed mem overlooked the ballot box which was kept in the office of the election registrar at the second floor of said municipal building. Said ballot box contained all the copies of the election returns of Libagon which were used in the municipal canvass. It is in the said office that said ballot box remained until a representative of the HRET went to Libagon on March 23 and 24, 1988 to take possession of the contents of the same particularly the election returns kept in said ballot box. On December 6, 1990, the Tribunal (by a vote of 5-4) promulgated its now assailed Decision, the pertinent portion of which reads: On the basis of all of the foregoing, and the supporting details as contained in ANNEXES A, B and C and in order to determine the final results of the elections for the position of

Precinct

Provincial Board of Canvassers's Copy 162 votes 123 " 132 " 156 "

Comelec Copy

"6 " 10 " 18 " 19

62 votes 23 " 32 " 56 "

Nevertheless, the Comelec, (Second Division) in its Resolution dated June 6, 1987, directed the provincial board of canvassers to complete the canvass by crediting Mercado 1,351 votes and Lerias 1,411 votes, the votes received by them, respectively, as shown in the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvas. So, on June 7, 1987, the provincial board of canvassers reconvened, resumed the canvass and proclaimed Mercado, as the winning candidate, having received the highest number of votes 35,793. Lerias, his closest rival, received 35,539 votes or a difference of 254 votes. On June 7, 1987, Lerias filed an urgent ex-parte motion for the reconsideration of the June 6, 1987 resolution. She prayed that the members of the municipal board of canvassers be summoned to testify on the authenticity and veracity of the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass and statement of votes submitted to the Comelec and that the election returns for precincts 6, 10, 18 & 19 be produced. On June 15, 1987 Lerias filed with the Comelec a petition (SPC No. 87-488) for the annulment of the canvass and proclamation of Mercado, praying that the ballot boxes of precints 6, 10, 18 & 19 of Libagon be ordered opened and the votes therein recounted. On June 21, 1987, she filed a motion to suspend the effects of the proclamation of Mercado.

Member of the House of Representatives, representing the lone district of Southern Leyte, a full and final RECAPITULATION is hereunder provided:

SO ORDERED. (pp. 136-137) The Chairperson of the Tribunal, the Honorable Justice Ameurfina M. Herrera dissented, in this wise: It becomes only too obvious then that by sheer force of numbers; by overturning, at the post-appreciation stage, the rulings earlier made by the Tribunal admitting the claimed ballots for Protestant Lerias; by departing from the interpretation of the neighborhood rule heretofore consistently followed by the Tribunal; by injecting `strange jurisprudence,' particularly on the intent rule; the majority has succeeded in altering the figures that reflect the final outcome of this election protest and, in the process, thwarting the true will of the electorate in the lone district of Southern Leyte. Premises Considered, I vote to declare Protestant Rosette Y. Lerias the winner in this election protest. To the plurality of 20 votes obtained by her in the counter-protested precincts according to the outcome of the appreciation of ballots, must be added the 400 votes that should have been counted in her favor in the municipality of Libagon. All told, Protestant Lerias should, therefore, be credited with a total of thirty six thousand eight (36,008) votes as against thirty five thousand five hundred eighty eight (35,588) votes for Protestee Mercado, or a margin of four hundred twenty (420) votes. (pp. 169-170 Rollo) Likewise, the Honorable, Justice Isagani Cruz, concurring with the dissent of Justice Herrera stated:

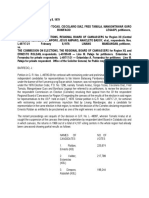

FINAL TABULATION Mercado Votes per tally of the Provincial Board of Canvassers, used to PROCLAIM protestee Mercado deduct: Votes per Election Returns from 81 protested precincts UNCONTESTED VOTES Add: Votes per REVISION (physicalcount) Totals Revision Results: deduct: Rejected Ballots (objected) Totals add: Claimed and ADMITTED Ballots 26 273 362 252 2,287 35,926 6,867 35,521 2,154 33,639 6,885 28,654 35,793 35,539 Lerias

I cannot help noting that, as in several earlier cases, all the five members representing the majority party are again voting together in favor of the Protestee, who also happens to belong to their party. Whatever this coincidence may import, I repeat my observation in the Ong cases (HRET Nos. 13 and 15, Nov. 6, 1989) that `although the composition of the Tribunal is predominantly legislative, the function of this body is purely judicial, to be discharged on the basis solely of legal considerations, without regard to political, personal and other irrelevant persuasions. (pp. 258-259, Rollo) The Honorable, Justice Emilio Gancayco (now retired) concurred with the dissent of Justices Herrera and Cruz. Another member of the Tribunal, Representative Antonio H. Cerilles, also in his dissent, stated: Going over all the foregoing facts and circumstances, Ihonestly fear that the majority decision will open the Tribunal to a charge of grave abuse of discretion in dismissing the protest and disallowing the admission of the results of Precinct Nos. 6, 10, 18 and 19 of the Municipality of Libagon, Southern Leyte, as reflected in the election returns, and the overwhelming documentary and testimonial evidences introduced, supported by well-settled jurisprudence. The same grave abuse of discretion may be said of the replacement of the results of the Screening Committee where protestant Lerias was originally a winner by twenty (20) votes over Mercado on the counter-protest alone, but which tabulation was reconsidered and ultimately replaced with a revised tabulation which altered the result, this time with protestee Mercado winning by forty-two (42) votes over Lerias, without any Identification and ocular review of the ballots of the protestant thus rejected and no proper showing of the grounds for such rejection. All these considered, I feel compelled to register my dissent to this shameful and blatant disregard of the evidence, the law, and the rudiments of fairness. I regret that the majority decision will lend truth to the suspicion that a protestant from an opposition party cannot secure substantial justice from this Tribunal. It is the perception of many that the odds are stacked against such party mainly because of the composition of the Tribunal, and no evidence, no law, no jurisprudence, not even elementary principles of fair play, equity or morality can outweigh a determined demonstration of party stand, partiality and bias. I will not be party to such travesty of justice. This is not the first time and it certainly will not be the last when I as the lone opposition member of this Tribunal joined the three Justices of the Supreme Court in dissent. But I do so guided no less by the pronouncement of Justice Isagani A. Cruz, a member of this Tribunal, when he said: `Whatever this division may imply, it is worth stressing that although the composition of the Tribunal is predominantly legislative, the function of this body is purely judicial, to be discharged, on the basis

35,564

35,269

35,590 add: Restored Votes FINAL RESULTS 0

35,542 2

35,590

35,544

(Protestee Mercado wins by a plurality of 46 votes) ACCORDINGLY, THE PROTEST of protestant Lerias is dismissed; and by virtue of the results of revision of the eighty one (81) counter-protested precincts, the Tribunal declares that protestee Mercado is the duly elected Representative of the Lone District of the Province of Southern Leyte, by a plurality of FORTY SIX (46) votes; having garnered a total of THIRTY FIVE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED NINETY (35,590) votes as against the THIRTY FIVE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED FORTY FOUR (35,544) votes of protestant Lerias. No pronouncement as to costs. WHEREFORE, as soon as this Decision becomes final, notice and copies of the Decision shall be sent to the President of the Philippines, the House of Representatives, through the Speaker, and the Commission on Audit, through its Chairman, pursuant to the Rules of the House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal, Section 28.

solely of legal considerations without regard to political, personal and other irrelevant persuasions. 1 (Emphasis supplied) I now indicate that I favor the admission of the results of the election returns of Precinct Nos. 6, 10, 18, and 19 of the Municipality of Libagon, Southern Leyte, and to return to protestant Lerias the 400 votes which was fraudulently taken away from her. Likewise, the original revision results of the screening of the ballots of the counter-protested precincts, as submitted to and previously approved by the Tribunal, which reflected that Lerias was ahead of Mercado by 20 votes, should be upheld. Protestant Lerias should thus be credited with a totality of 36,008 votes as against 35,588 votes of protestee Mercado, in a final untarnished count. Protestant, should, therefore, be declared the winner in the May 11, 1987 election for the Lone District of Southern Leyte, having obtained a majority of the valid votes cast in the said election, with a plurality of four hundred twenty (420) votes over the protestee, and thus, further declare protestant Rosette Y. Lerias as the duly elected Representative of the Lone District of Southern Leyte. (Rollo, pp. 287-189) Lerias filed a motion for reconsideration. Mercado also filed a partial motion for reconsideration. Acting on the said motions, the Tribunal, on January 31, 1991 promulgated its assailed Resolution, the dispositive portion of which reads: WHEREFORE, the Tribunal Resolved to DENY protestant's Motion for Reconsideration for lack of merit. Protestee's Partial Motion for Reconsideration, is hereby GRANTED. The Tribunal also DIRECTS motu propio the appropriate correction of the `Votes per Revision' of the Protestant, pursuant to the verified errors committed, so as to reflect the true and correct votes actually garnered by the protestant and the protestee. ACCORDINGLY, the Decision of the Tribunal promulgated on December 6, 1990 is hereby amended and modified, by declaring protestee Mercado as the duly elected Representative of the Lone Legislative District of the Province of Southern Leyte, by a plurality of SIXTY SEVEN (67) VOTES,having garnered a total of THIRTY FIVE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED NINETY FIVE (35,595) VOTES, as against the THIRTY FIVE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED TWENTY EIGHT (35,528) VOTES of protestant Lerias. (pp. 344, Rollo) In her revised Dissenting Opinion, (pp. 346-353 Rollo) the Honorable Justice Herrera made the following clarifications: Interpolating the necessary corrections, therefore, the final tabulation of votes obtained by the parties in the counterprotested precincts should be revised as follows:

Deduct: Rejected ballots TOTAL 363 35,568 (formerly 35,563)

Add: Claimed ballots admitted (as corrected) Add: votes restored TOTAL VOTES 25 0

35,593 (formerly 35,588)

Plurality of Protestant Lerias 12 votes (instead of20 in the original dissent) To this plurality of twelve (12) votes obtained by Protestant Lerias in the counter-protested precincts must be added the 400 votes obtained by her in the four contested precincts in Libagon. Protestant Lerias should, therefore, be credited with a total of thirty six thousand five (36,005) votes as against thirty five thousand five hundred ninety three (35,593) votes for Protestee Mercado, or a margin of four hundred twelve (412) votes, instead of the 420 votes in the original dissent. PREMISES CONSIDERED, in so far as the undersigned's dissent is concerned, Protestee Mercado's Partial Motion for Rreconsideration is denied, and I reiterate my vote to proclaim Protestant Rosette Y. Lerias as the fully elected Representative for Southern Leyte. (pp. 351-353, Rollo) Justice Cruz maintained his original dissent. Representative Cerilles filed a "Dissenting Opinion on Denial of Protestant's Motion for Reconsideration" (pp. 355-357 Rollo) stating that : In sum, Protestant should therefore be declared winner in the May 11, 1987 election for the Lone District of Southern Leyte having obtained a plurality of four hundred four (404) votes over the Protestee, and thus further declare Protestant Rosette Y. Lerias as the duly elected Representative of the Lone District of Southern Leyte. (pp. 356-357, Rollo) We have read and examined, with utmost interest and care, the contentions of the parties, the majority opinion of the five members of the Tribunal as well as the separate dissenting opinions of the chairperson and some members of the electoral LERIAS tribunal, and the Court arrived at the conclusion, without any hesitation, reservation, or doubt, that the Tribunal (the majority opinion) in rendering its questioned Decision and Resolution had acted whimsically and arbitrarily and with very grave abuse of discretion. It is for this reason that We cannot bring ourselves to agree with their35,539 decision. The Protest Lerias contended that in the four (4) protested precincts of Libagon where her votes were determined to be 1,411 only, the same were allegedly reduced by 100 votes in each precinct, thus totalling 400, the details of which reduction are as follows: 2,154 6,885 Prec inct 33,639 28,654 Prot este d Ler ias' Ler ias ' Cla im ed Vo tes 16 2 12 3 13 2

MERCADO Votes per proclamation Deduct: Votes in 81 counter-protested precincts VotesUncontested precincts Add: Votes per revision (physical count, as corrected 2,292 (formerly 2,287) 35,931 (formerly 35,926) 35,793

Cre dit ed Vot es 62

No. 6 No. 6,851 (formerly 10 6,867) No. 35,256 (formerly 18 35,521)

23

TOTAL

32

No. 19

56

15 6

Should her claimed votes as aforestated be sustained Lerias' total votes from the municipality of Libagon shall be 1,811 votes. In such an eventuality, Lerias shall have been able to recover 400 votes, more than sufficient to overcome the winning margin of Mercado, thereby prevailing by a plurality of 146 votes. To prove her contention, Lerias submitted original copies of the certificate of canvass of the municipal board of canvassers and the provincial board of canvassers. She also invoked the original copy of the election returns for the municipal board of canvassers of Libagon. These documents, particularly the election returns showed that Lerias received 162 votes in Prec. No. 6, 123 votes in Prec. No. 10, 132 votes in Prec. No. 18 and 156 votes in Prec. No. 19 to give her a total of 1,811 votes in the entire municipality of Libagon. Upon the other hand, Mercado relied mainly on the xerox copy of the certificate of canvass for the Comelec. This certificate showed that Lerias received 62 votes in Prec. No. 6, 23 votes in Prec. No. 10, 32 votes in Prec. No. 18 and 56 votes in Prec. No. 19. The HRET majority opinion rejected the election returns and sustained the certificate of canvass because (1) the Comelec found that the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass is "regular, genuine and authentic on its face" and said finding of the Comelec had been sustained by the Supreme Court; (2) the protestant (meaning Lerias) had agreed during the pre-proclamation proceedings to the use of the Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass; and (3) the authenticity of the election returns from the four (4) disputed precincts had not been established. The reasons given by the majority for doubting the authenticity of the election returns are: (a) the non-production of the election returns during the entire preproclamation proceedings definitely creates much doubt as to their authenticity especially so when they surfaced only almost a year later after the ballots had been stolen; (b) during that time, the election returns may have been tampered with and "doctored" to Lerias' advantage; (c) no proof whatsoever was offered to show that the integrity of the ballot box in which they were kept was not violated; and (d) thewitnesses presented by Lerias had shown their partisanship in her favor by executing affidavits to support her protest. The foregoing findings and pronouncements of the HRET (majorirty opinion) are totally bereft of any support in law and settled jurisprudence. In an election contest where what is involved is the correctness of the number of votes of each candidate, the best and most conclusive evidence are the ballots themselves. But where the ballots cannot be produced or are not available, the election returns would be the best evidence. Where it has been duly determined that actual voting and election by the registered voter had taken place in the questioned precincts or voting centers, the election returns cannot be disregarded and excluded with the resulting disenfranchisement of the voters, but must be accorded prima facie status as bona fide reports of the results of the voting. Canvassing boards, the Comelec and the HRET must exercise extreme caution in rejecting returns and may do so only upon the most convincing proof that the returns are obviously manufactured or fake. And, conformably to established rules, it is the party alleging that the election returns had been tampered with, who should submit proof of this allegation. At this juncture, it is well to stress that the evidence before the HRET is the original copy of the election returns while the Comelec's copy of the certificate of canvass, is merely a xerox copy, the original thereof had not been produced. Under the best evidence rule, "there can be no evidence of a writing, the contents of which are the subject of inquiry, other than the original writing itself" except only in the cases enumerated in Rule 130, Sec. 2 of the Rules of Court. The exceptions are not present here. Moreover, the xerox copy of the certificate of canvass is inadmissible as secondary evidence because the requirements of Sec. 4 of the same Rule have not been met. (Dissent of J. Cruz, p. 254) Besides this certificate of canvass had been disowned by the chairman and members of the municipal board of canvassers, claiming that the same was falsified since their signatures and thumbmarks appearing thereon are not theirs and the number of votes credited to Lerias in the municipality of Libagon had been reduced from 1,811 to 1,411. (TSN, Sept. 13, 1988 AM, pp. 74-78; TSN, Sept. 13, 1988 PM, pp. 41-46; Dissenting Opinion, Rep. A.H. Cerilles, p. 2) The finding of the Comelec in the pre-proclamation proceedings that its copy of the certificate of canvass is "genuine and authentic" and which finding was sustained by this Court (G.R. No. 78833; 79882-83) is not binding and conclusive. The HRET must be referring to the following portion of the decision of this Court Public interest demands that pre-proclamation contests should be terminated with dispatch so as not to unduly deprive the people of representation, as in this case, in the halls of Congress. As the Court has stressed in Enrile v. Comelec, and other cases, the policy of the election law is that pre-proclamation controversies should be summarily decided, consistent with the law's desire that the canvass and proclamation should be delayed as little

as possible. The powers of the COMELEC are essentially executive and administrative in nature and the question of fraud, terrorism and other irregularities in the conduct of the election should be ventilated in a regular election protest and the Commission on Elections is not the proper forum for deciding such matters; neither the Constitution nor statute has granted the COMELEC or the board of canvassers the power, in the canvass of elections returns to look beyond the face thereof `once satisfied of their authenticity'. We believe that the matters brought up by petitioner should be ventilated before the House Electoral Tribunal. Unlike in the past, it is no longer the COMELEC but the House Electoral Tribunal which is `the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns, and qualifications' of the members of the House of Representatives. In opting to go by the COMELEC copy which on its face did not show any alteration, the COMELEC did not commit any grave abuse of discretion, specially since both parties agreed to the COMELEC using its own copy (Copy No. 3). Accordingly, the Court resolved to DISMISS the petition for lack ofmerit. The temporary restraining order issued on July 23, 1987 is hereby LIFTED effective immediately. (Rollo, pp. 264-265) It would appear, therefore, that this Court sustained the use of the Comelec's copy of the certificate of canvass instead of the copy of the provincial board of canvassers only to establish prima facie (but not actually) the winner (as called for by the summary nature of pre-proclamation proceedings), without prejudice to a more judicious and unhurried determination in an election protest, and because Lerias' thru counsel had previously agreed conditionally and qualifiedly to its tentative use for pre-proclamation proceedings. The decision of this court was merely an affirmance of the action of the Comelec and it cannot be relied upon as a final adjudication on the merits, on the issue of the genuiness and authenticity of the said certificate of canvass. Besides, the use of said Comelec copy of the certificate of canvass by the board of canvassers did not foreclose the right of Lerias to prove that the votes attributed to have been received by her as stated, in said certificate of canvass is not correct. Acceptance of a certificate of canvass as genuine and authentic for purposes of canvass simply means that said certificate of canvass is genuine and authentic for the purpose of determining the prima facie winner in the election. But the very purpose of an election contest is to establish who is the actual winner in the election. Anent the pronouncement of the HRET (majority opinion) that having agreed to the use of the Comelec's copy of the certificate of canvass, Lerias is now estopped from assailing it, suffice it to state that Lerias agreed to the use of said copy because she was not aware then that the figures therein had been altered. It is a matter of record that she immediately objected after she discovered the discrepancy. At any rate, she cannot be estopped from protesting a falsification of the voters' will because such estoppel would contravene public policy. (Dissent of J. Cruz, p. 5) Moreover, as indicated in the discussion hereinabove, under the circumstances relating to pre-proclamation, estoppel certainly cannot apply. As to the delay in presenting the election returns because these were not presented during the whole pre-proclamation proceedings, it must be noted that at that time, the four ballot boxes of Libagon with their correspondidng ballots were still intact and as these would have provided the best evidence, resorting to the election returns was uncalled for. It is for this reason that Lerias had asked for a recount of the ballots and this would have obviated the need for the election returns. Under these circumstances the failure of Lerias to ask for the production of the election returns during those times that the ballots were still available cannot be considered as ground for considering said election returns as of dubious character. The "suspicion" of the HRET (majority opinion) regarding the possible tampering of the election returns are at best merely speculative and dispelled by the incontrovertible evidence in the case. On its face, these election returns have no traces of tampering. Even the majority decision admits that said election returns "appear to be originals and on their faces, authentic." (Decision, p. 21) The authenticity of said returns, particularly those of Precincts 6, 10, 18, and 19, the four disputed precincts, had been further established by the testimonies of the members of the Board of Election Inspectors of said precincts during the hearing before the Tribunal and before the hearing officer designated to hear the case. More importantly, examination of said returns conclusively established the Identity of said returns as the very same ones prepared by the respective Board of Election Inspectors during the counting of the votes. The election returns for Precinct 6 was marked as Exhibit "F"; that of Precinct 10, Exhibit "AA"; Precinct 18, Exhibit "U", and Precincts 19, Exhibit "P". The election returns for Precinct 6 bears Serial No. 0138; for Precincts 10, No. 0142; for Precinct 18, No. 0150; and for Precinct 19, No. 0151. The minutes of voting for each of said precincts which were submitted to the Comelec and later on presented in evidence before the Tribunal, indicated the serial numbers of the election returns for said precincts and they corresponded to the serial numbers of election returns for the four precincts. The NAMFREL reposts, (copy from the National Headquarters) which were presented during the initial hearing before the HRET by a representaive of the national headquarters of NAMFREL, as well as the copies of said reports of Bencouer Gado, the municipal coordinator of NAMFREL in Libagon, also indicated that the election returns for Precinct 6 bears Serial No. 0138; Precinct 10, Serial No.

0142; Precinct 18, Serial No. 0150 and Precinct 19, Serial No. 0151. 2 The envelopes wherein said election returns were originally placed by the Board of Election Inspectors from said precincts, when they turned over said election returns to the election registrar, were the very same envelopes which contained the election returns from said precincts at the time that they were turned over to Luspo (the Tribunal's representative) on March 24, 1988. The Identity of said envelopes had been conclusively proven by the fact that the serial numbers that they bear and the Comelec paper seal sealing said envelopes are the same. The serial numbers of said envelopes had been noted in the minutes of each of said proceedings. The envelope containing the election returns for Precinct 6 bears Serial No. 042366 and the Comelec paper seal thereof bears Serial No. 017318. The envelope containing the election returns for Precincts 10 bears Sereial No. 042370 and the Comelec paper seal thereof bears Serial No. 0173226. The envelope containing the election returns for Precinct 18 bears Serial No. 04373 while the Comelec paper seal thereof bears Serial No. 0173326. The envelope containing the election returns for Precinct 19 bears Serial No. 042379 while the Comelec paper seal thereof bears Serial No. 173332. When the chairmen of each of said precincts testified before the Hearing Officer designated by the Tribunal, they all Identified their respective signatures and thumbmarks appearing on the envelopes for said four precincts. Ruego, the chairman of the Municipal Board of Canvassers and acting election registrar during the election, also Identified his signature on the envelopes acknowledging the receipt of said envelopes containing the election returns for said precincts. The four chairmen of said precincts also positively Identified that the election returns shown to them for their respective precincts taken from the custodian of the Tribunal and placed inside Envelopes A and B were the very same election returns prepared by them. They Identified their own signatures and thumbmarks and those of the other members of the board of election inspectors in their respective precincts. On the basis of the election returns from the four disputed precincts, the votes of Lerias and Mercado in said precincts were as follows: