Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Long-Term Debt Management

Transféré par

Namrata PatilDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Long-Term Debt Management

Transféré par

Namrata PatilDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Long-Term Debt Management Borrowing to undertake capital projects can help an organization grow.

But, if not done properly, it can kill one. Consider the true stories of two organizations. by Woods Bowman, Ph.D. Borrowing to undertake capital projects can help an organization grow. But, if not done properly, it can kill one. Consider the true stories of two organizations. University As strategic plan called for doubling its student population over 15 years. Mark eting surveys indicated that it was at a competitive disadvantage because key student support facilities were either nonexistent or outdated. With a weak development office, it had no choice but to borrow. It issued tax-exempt bonds at favorable rates and it achieved its enrollment growth goal. Human Services Agency B had no strategic plan. It wanted to buy a headquarters building to save on property taxes. It bought a building with three times more floor area than it had been renting with money borrowed from a bank at market rates. It expected to lose money until it was able to expand program activity, but it did not expand and eventually it was forced out of business through merger. What can we learn from these examples? Have a plan based on market surveys or other credible information explicitly linking borrowed resources with specific outputs, and never borrow without adequate cash flow to support debt service (principal and interest). Before you borrow, analyze the impact the new debt will have on your o rganizations financial health. To make the discussion concrete, assume new borrowing is used to acquire a building. With no down payment, there will be a new asset on your balance sheet (the building) but also a new liability of equal size (the debt). A down payment reduces the borrowed principal, but it also reduces the cash on your balance sheet. Either way, there is no change in your net assets as a direct and immediate result of borrowing. Things go down hill from here. Over the life of the loan, the value of the building on your financial statements will gradually melt away, and net assets will decrease unless the new building generates revenue or reduces expenses in excess of interest and depreciation an accounting construct that describes how fast you are consuming, or using up, the building you just bought. This was Agency Bs problem: its new building did not help it to produce new revenue. Interest payments alone exceeded property tax savings. If you are thinking about borrowing, it is important to understand your creditors. Before lending, they will look at the relationship between various numbers on your financial statements. This article will serve as an introduction to the techniques they use to size you up. You should analyze your situation as they would. Your creditors first concern is getting their principal back, with interest, on an agreed-upon schedule. They have first claim on revenue, but they are mindful that financially strapped organizations occasionally succumb to the temptation to suspend debt service payments. You must convince them that your current cash flow is sufficient to service the debt you propose to undertake, and you have a sufficient financial cushion in case of an unforeseen reversal of fortune. Creditors want assurance that (1) the borrowers historical operating surplus is sufficient to support debt service and (2) the borrower has enough net assets to provide a cushion in the event of a sudden, unanticipated drop in revenue. The size of the cushion determines the bor rowers debt capacity, or the maximum amount it can borrow. This article draws upon the experiences

that Standard & Poors (S&P) and Moodys Investors Service have had rating the creditworthiness of nonprofit bond issuers, i.e. borrowers. Consider debt capacity first. S&P wants the sum of unrestricted net assets and temporarily restricted net assets to be at least three months of average annual operating expenses (not counting depreciation), although it would prefer to see something in excess of six months. Another measure of debt capacity is the debt-toequity ratio. S&P wants total debt, including the new borrowing, to be no greater than half of the sum of unrestricted net assets and temporarily restricted net assets minus the equity in physical assets, which are illiquid and unavailable to service debt should operating losses occur. The next question is whether operating surplus will be sufficient to make principal and interest payments. S&P wants a borrowers operating surplus plus depreciation to be at least twice its projected debt service. The multiple is called coverage. Three is good, and five is excellent. Operating income excludes donations that are permanently restricted or appear to be nonrecurring. Moodys also excludes one-time items from expenses. If the borrower has significant investment income, S&P includes interest income and realized capital gains on investment in the calculation of operating surplus, provided the total does not exceed the organizations policy on spending investment income. Moodys, on the other hand, simply counts 5 percent of an organizations cash, investments and endowment as operating income. Moodys Investors Service considers similar factors, but it is also very interested in the ratio of operating surplus to operating revenue, a concept called operating margin. It does not set a minimum for each factor. Median operating margins for Moodys rated debt in categories of different investment quality varies between 0.4% and 4.1%. Median coverage ranges from 2 to 3. Median debt-to-equity ratios range from 1.5 to 0.12. Creditors favor organizations with a strong source of earned income, such as admissions and ticket sales, that enjoy a secure market niche because they are in a good position to raise their prices to support debt service, if necessary. Once you decide whether and how much to borrow, the next question is: borrow from a bank or issue bonds? All nonprofit organizations are able to borrow in the public bond market, but only 501(c)(3)s can team up with state and local governments to issue bonds that are exempt from federal income taxes. The bonds can be secured either with a physical asset, revenues generated by the project, or simply the full faith and credit of the issuer. In any case, 501(c)(3)s can achieve substantial savings in interest costs. Under current market conditions savings are unusually modest, but they are likely to improve as market rates rise, as most experts expect. There are issuance costs associated with bond transactions so, if the principal is less than a few million dollars, selling bonds in the public market is not likely to be cost-effective. A private placement (when one investor buys all of the bonds) or a bank loan is likely to be more efficient, although interest payments on bank loans are not tax-exempt, and therefore bank rates are higher. When it comes to taking on new debt, endowed 501(c)(3)s have a tremendous advantage. Not only do they have a prodigious debt capacity, they can actually make money by going into debt. To illustrate: assume a 501(c)(3) has $100 million in unrestricted net assets, $7 million in cash and short-term investments, and it wants to build a $3 million building. It could pay cash but, if it

issued tax-exempt bonds, it would earn a higher market rate on its investments than it would pay on its bonded indebtedness. A difference of one percentage point over 20 years would generate a net cash flow of $167,000 a year. This example assumes fixed rate bonds, much like a conventional mortgage. Although it is possible to issue bonds at variable interest rates, this is probably unwise under current conditions because rates are at historic lows. They are more likely to go up than down. Allowable purposes for tax-exempt debt are: capital expenditure projects, reimbursing prior capital expenditures, refinancing of prior debt, and working capital. These purposes can be combined in one issue. Proceeds can reimburse money spent before they were issued only if the issuer adopts a resolution officially expressing its intent to reimburse such expenditures, and feasibility studies can be expensive. An official intent resolution does not obligate an organization to undertake the specified project, so adopting one should be the first order of business when thinking about a capital expenditure project. The Dos and Donts of borrowing are simple. Do not borrow to finance budget deficits. Do not borrow unless you have a clear understanding of your growth potential and how debt will help you fulfill that potential. Never borrow to finance operating deficits. Do not borrow unless you have adequate capacity, you can service the debt, and it will strengthen your balance sheet. Do issue tax exempt bonds if you are a 501(c)(3), and if the principal is large enough. Woods Bowman is Associate Professor of Public Service Management at DePaul University in Chicago . He is also a member of the National Center on Nonprofit Enterprises Research Advisory Network. Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds (FCCB) Foreign currency convertible bond (FCCB) is a convertible bond issued by a country in a currency different than the its own currency. This is the powerful instrument by which the country raises the money in the form of a foreign currency. The bond acts like both a debt and equity instrument. Like bonds it makes regular coupon and principal payments, but these bonds also give the bondholder the option to convert the bond into stock. Foreign Currency Convertible Bond Policy in India Ministry of Finance government of India defines FCCB. According to it: "Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds" means bonds issued in accordance with this scheme and subscribed by a non- resident in foreign currency and convertible into ordinary shares of the issuing company in any manner, either in whole, or in part, on the basis of any equity related warrants attached to debt instruments; " What is the criteria for issuing FCCBs? Any company who wish to raise the foreign funds by issuing FCCB, require prior permission of the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India. The company issuing the FCCB should have the consistent track record for a minimum period of three years The Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds shall be denominated in any freely convertible

foreign currency and the ordinary shares of an issuing company shall be denominated in Indian rupees The issuing company should deliver the ordinary shares or bonds to a Domestic Custodian Bank as per regulation. The custodian bank on the other hand instructs the Overseas Depositary Bank to issue Global Depositary Receipt or Certificate to non-resident investors against the shares or bonds held by the Domestic Custodian Bank. The provisions of any law with regard to the issue of capital by an Indian company will also be applicable the issue of Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds or the ordinary shares of an issuing company. The company issuing FCCB, shall obtain the necessary permission or exemption from the appropriate authority under the relevant law relating to issue of capital. Limits of foreign investment in the issuing company The Ordinary shares and Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds (FCCB) that are issued against the Global Depository Receipts are treated as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). However total foreign investment made either directly or indirectly shall not exceed 51% of the issued and subscribed capital of the issuing company. Taxation on Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds Until the conversion option is exercised, all the interest payments on the bonds, is subject to deduction of tax at source at the rate of ten per cent Tax exercised on dividend on the converted portion of the bond is subject to deduction of tax at source at the rate of ten per cent If Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds ( FCCB ) is converted into shares it will not give rise to any capital gains liable to income- tax in India. If Foreign Currency Convertible Bonds (FCCB) is transferred by a non-resident investor to another non-resident investor it shall not give rise to any capital gains liable to tax in India.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Modern Debt Management - The Most Effective Debt Management SolutionsD'EverandModern Debt Management - The Most Effective Debt Management SolutionsPas encore d'évaluation

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 46, Urgent Care Center FinancingD'EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 46, Urgent Care Center FinancingPas encore d'évaluation

- There Are Many Different Motivations To Source MoneyDocument7 pagesThere Are Many Different Motivations To Source MoneyJamaica RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Bonds vs Bank Loans for Firm FundingDocument7 pagesCorporate Bonds vs Bank Loans for Firm FundingYssa MallenPas encore d'évaluation

- CH - 15 Financial Management: Core ConceptsDocument35 pagesCH - 15 Financial Management: Core ConceptsLolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Leveraged Buyouts: A Practical Introductory Guide to LBOsD'EverandLeveraged Buyouts: A Practical Introductory Guide to LBOsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Mastering Your Finances: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding, Managing, and Leveraging Good vs Bad DebtD'EverandMastering Your Finances: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding, Managing, and Leveraging Good vs Bad DebtPas encore d'évaluation

- Bonds Decoded: Unraveling the Mystery Behind Bond MarketsD'EverandBonds Decoded: Unraveling the Mystery Behind Bond MarketsPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 19,20,21,22 Assesment QuestionsDocument19 pagesChapter 19,20,21,22 Assesment QuestionsSteven Sanderson100% (3)

- Long-Term Debt and Lease FinancingDocument2 pagesLong-Term Debt and Lease FinancingJEVELYN N. DABALOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review On Loan DisbursementDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Loan Disbursementaflssjrda100% (2)

- Fin358 Individual Assignment (Bond)Document9 pagesFin358 Individual Assignment (Bond)nur hazaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Loan Discounts Finance 7Document41 pagesLoan Discounts Finance 7Elvie Anne Lucero ClaudPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms FinanceDocument17 pagesTerms FinanceAshutosh SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Bus. Finance 2. Final 2.Document9 pagesBus. Finance 2. Final 2.Gia PorqueriñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 3Document4 pagesAssignment 3arina7Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Materiality Concept in Financial ReportingDocument6 pagesThe Materiality Concept in Financial ReportingkunalPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Assignment: Department of Business AdministrationDocument14 pages2 Assignment: Department of Business AdministrationFarhan KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Finance - Unit IV - Cao My Duyen - HOM59Document7 pagesCorporate Finance - Unit IV - Cao My Duyen - HOM59Duyên CaoPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 2 PUBLIC EXPENDITURE POLICYDocument20 pagesCHAPTER 2 PUBLIC EXPENDITURE POLICYMaricel GoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fund Base: Cash CreditDocument6 pagesFund Base: Cash CreditLakshmi Ramya SilpaPas encore d'évaluation

- Approved: How to Get Your Business Loan Funded Faster, Cheaper, & with Less StressD'EverandApproved: How to Get Your Business Loan Funded Faster, Cheaper, & with Less StressÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Loan Management Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesLoan Management Literature Reviewixevojrif100% (1)

- Assignment For BM...Document9 pagesAssignment For BM...Anonymous xOqiXnW9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Working Capital Management (GROUP 5)Document33 pagesWorking Capital Management (GROUP 5)Cyrylle AngelesPas encore d'évaluation

- Banking: Islamic Banking: Institute of Business Administration (Iba), JuDocument8 pagesBanking: Islamic Banking: Institute of Business Administration (Iba), JuYeasminAkterPas encore d'évaluation

- Banks' Lending Functions and Loan ProductsDocument26 pagesBanks' Lending Functions and Loan ProductsAshish Gupta100% (1)

- BBA2030493Document14 pagesBBA2030493Saad AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Debt Obligation: Refinancing May Refer To The Replacement of An ExistingDocument8 pagesDebt Obligation: Refinancing May Refer To The Replacement of An ExistingMani MaranPas encore d'évaluation

- ReceivablesExchange Whitepaper Bank Loan CovenantsDocument7 pagesReceivablesExchange Whitepaper Bank Loan Covenantskvnumashankar100% (1)

- Copy of Create a Pictorial Representation on the Five C Principles of Lendi_20240401_110846_0000Document11 pagesCopy of Create a Pictorial Representation on the Five C Principles of Lendi_20240401_110846_0000mohankumar12tha1Pas encore d'évaluation

- CLD - BAO3404 TUTORIAL GUIDE WordDocument49 pagesCLD - BAO3404 TUTORIAL GUIDE WordShi MingPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis On Sources of FinanceDocument4 pagesThesis On Sources of Financeleslylockwoodpasadena100% (2)

- LBO TutorialDocument8 pagesLBO Tutorialissam chleuhPas encore d'évaluation

- FinanceDocument68 pagesFinanceAngelica CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- How Debt Generates Income: A Practical Guide to Leveraging Other People's Money - Debt Income Systems for Long-Term WealthD'EverandHow Debt Generates Income: A Practical Guide to Leveraging Other People's Money - Debt Income Systems for Long-Term WealthPas encore d'évaluation

- Bridge FinancingDocument11 pagesBridge Financingdimpleshetty100% (1)

- Credit Analyst Questions and Answers 1693198236Document9 pagesCredit Analyst Questions and Answers 1693198236hh2rwfs8f5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Managemnt of Capital in BanksDocument8 pagesManagemnt of Capital in Banksnrawat12345Pas encore d'évaluation

- Coperate FinanceDocument17 pagesCoperate Financegift lunguPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A Loan?: Open-Ended Line of CreditDocument13 pagesWhat Is A Loan?: Open-Ended Line of CreditJohn Matthew JoboPas encore d'évaluation

- Vce ST01 FMDocument4 pagesVce ST01 FMSourabh ChiprikarPas encore d'évaluation

- How to Raise your Credit Score: Proven Strategies to Repair Your Credit Score, Increase Your Credit Score, Overcome Credit Card Debt and Increase Your Credit Limit Volume 2D'EverandHow to Raise your Credit Score: Proven Strategies to Repair Your Credit Score, Increase Your Credit Score, Overcome Credit Card Debt and Increase Your Credit Limit Volume 2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ms 41Document12 pagesMs 41kvrajan6Pas encore d'évaluation

- UNIT 5 Working Capital FinancingDocument24 pagesUNIT 5 Working Capital FinancingParul varshneyPas encore d'évaluation

- Loan CovenantDocument7 pagesLoan CovenantpokasdfPas encore d'évaluation

- Commercial Banks Funding and LendingDocument5 pagesCommercial Banks Funding and LendingHeri LimPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.what Is Debenture?: AnswersDocument16 pages1.what Is Debenture?: Answerssirisha222Pas encore d'évaluation

- Capital StructureDocument57 pagesCapital StructureRao ShekherPas encore d'évaluation

- A. Discuss The Advantages of Financing Capital Expenditures With DebtDocument5 pagesA. Discuss The Advantages of Financing Capital Expenditures With DebtMark SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Tutorial 1 AnswerDocument6 pagesTutorial 1 AnswerPuteri XjadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Report in Entreprenuerial MindDocument21 pagesWritten Report in Entreprenuerial MindAndrea OrbisoPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Report in Entreprenuerial MindDocument21 pagesWritten Report in Entreprenuerial MindAndrea OrbisoPas encore d'évaluation

- How Much Debt is Too MuchDocument5 pagesHow Much Debt is Too MuchreezakusumaPas encore d'évaluation

- ScotiaBank AUG 09 Daily FX UpdateDocument3 pagesScotiaBank AUG 09 Daily FX UpdateMiir ViirPas encore d'évaluation

- Material Requirements PlanningDocument38 pagesMaterial Requirements PlanningSatya BobbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Organigrama Ypfb 20180208Document1 pageOrganigrama Ypfb 20180208Ana PGPas encore d'évaluation

- Pacific Oxygen Vs Central BankDocument3 pagesPacific Oxygen Vs Central BankAmmie AsturiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Number of Months Number of Brownouts Per Month: Correct!Document6 pagesNumber of Months Number of Brownouts Per Month: Correct!Hey BeshywapPas encore d'évaluation

- Bulats Bec Mock 1 2020-11Document7 pagesBulats Bec Mock 1 2020-11api-356827706100% (1)

- PALATOS2023FDocument132 pagesPALATOS2023FMicah SibalPas encore d'évaluation

- MITS5001 Project Management Case StudyDocument6 pagesMITS5001 Project Management Case Studymadan GairePas encore d'évaluation

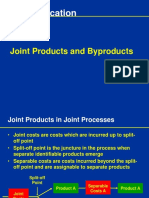

- Joint Cost Allocation Methods for Multiple ProductsDocument17 pagesJoint Cost Allocation Methods for Multiple ProductsATLASPas encore d'évaluation

- Estado Bancario ChaseDocument2 pagesEstado Bancario ChasePedro Ant. Núñez Ulloa100% (1)

- NusukDocument2 pagesNusukJib RanPas encore d'évaluation

- Merrill Lynch Financial Analyst BookletDocument2 pagesMerrill Lynch Financial Analyst Bookletbilly93Pas encore d'évaluation

- Labrel CBA Counter Propo Part 1Document12 pagesLabrel CBA Counter Propo Part 1TrudgeOnPas encore d'évaluation

- Process Analysis: SL No Process Proces S Owner Input Output Methods Interfaces With Measure of Performance (MOP)Document12 pagesProcess Analysis: SL No Process Proces S Owner Input Output Methods Interfaces With Measure of Performance (MOP)DhinakaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Basel 1 NormsDocument12 pagesBasel 1 NormsamolreddiwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of Money and its EvolutionDocument3 pagesDefinition of Money and its EvolutionMJ PHOTOGRAPHYPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Analysis of Marketing Strategies in Financial ServicesDocument69 pagesComparative Analysis of Marketing Strategies in Financial ServicesSanjana BansodePas encore d'évaluation

- Test Bank For Corporate Finance 4th Canadian Edition by BerkDocument37 pagesTest Bank For Corporate Finance 4th Canadian Edition by Berkangelahollandwdeirnczob100% (23)

- Case Study On Citizens' Band RadioDocument7 pagesCase Study On Citizens' Band RadioরাসেলআহমেদPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 Public FacilitiesDocument2 pages9 Public FacilitiesSAI SRI VLOGSPas encore d'évaluation

- Forex Extra QuestionsDocument9 pagesForex Extra QuestionsJuhi vohraPas encore d'évaluation

- Marine Plastics Pollution SingaporeDocument3 pagesMarine Plastics Pollution SingaporetestPas encore d'évaluation

- PPGE&C Payroll 22 022422gDocument1 pagePPGE&C Payroll 22 022422gjadan tupuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment On Banking & InsuranceDocument11 pagesAssignment On Banking & InsuranceRyhanul IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Manajemen Fungsional Pertemuan 1Document64 pagesManajemen Fungsional Pertemuan 1ingridPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1ADocument5 pagesAssignment 1Agreatguy_070% (1)

- Kalamba Games - 51% Majority Stake Investment Opportunity - July23Document17 pagesKalamba Games - 51% Majority Stake Investment Opportunity - July23Calvin LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Franchising Activities in VietnamDocument5 pagesOverview of Franchising Activities in VietnamNo NamePas encore d'évaluation

- E-Business Adaptation and Financial Performance of Merchandising Business in General Santos CityDocument9 pagesE-Business Adaptation and Financial Performance of Merchandising Business in General Santos CityTesia MandaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Business Processes: © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing As Prentice HallDocument20 pagesOverview of Business Processes: © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing As Prentice HallCharles MK ChanPas encore d'évaluation