Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Tutorial - Spey-Dee Fly

Transféré par

jfargnoliCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tutorial - Spey-Dee Fly

Transféré par

jfargnoliDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

February 12, 2006 Spey/Dee fly Tutorial Presenter: Cameron Derbyshire Welcome to this step by step instructional.

I will focus my attention on the tying of the fly and provide detailed instructions and photographs of how to tie this style of fly for steelhead, Atlantic salmon, sea trout, and, in smaller versions, trout. I leave the long history of this style of fly to John Shewey and Bob Veverka (see references at end). Throughout the tying instructions, my descriptions may seem extremely detailed, to the point of being overly anal. My intention is to help you be able to tie a fly you would feel comfortable framing for the wall. I will mention in the steps where you can save time and effort and still produce an effective fishing fly. The extra steps and time are aimed at the most discriminate tyer critiquing her or his flies. Furthermore, all the steps and techniques presented here are equally applicable to tying classic Atlantic salmon flies. Only some of the materials change. The point of this exercise is educational. To meet that goal, I included some comments of my own in the tying instructions to rationalize what I do and why. There are very good reasons for what I have done at some points in tying this fly. I aimed at explaining what options you have at certain points so you know that there are more than what is presented here. I chose materials that will show up well in the photographs. The hackles, tinsel, wire, and body materials stand out on their own. The exercise fly is tied just for this step by step instructional. Just by varying the size and colors, you can have a pattern to cover winter and summer steelhead. In addition, I have included how to tie on a blind eye hook in this tutorial. Please read through the entire tutorial prior to tying the fly. I would appreciate any feedback, comments, and criticism, either on the board or via e-mail (derbyshc@hotmail.com). If you would like a copy of this tutorial, I have it in both Microsoft Word (.doc) and Adobe Acrobat (.pdf) formats. Just send me a private message on the board or to my email address, and I will send you a copy of it in the requested format to your e-mail address. Here are the ingredients for this fortnights example fly:

Spey Dee Fly

Hook: Partridge Traditional Bartleet CS10/1 #1 Thread: Black 8/0 unwaxed Tip: Fine or small oval silver tinsel Tag: Yellow floss Tail: Chartreuse hackle fibers Ribs: (1) small silver wire (2) silver twist Body hackle: Natural blue eared pheasant flank feather Body: rear 2/3 orange floss front 1/3 red floss Front hackle: Natural guinea fowl flank or lower back feather Wings: Turkey tail, goose flank, or bronze mallard quill slips or 2-4 hackle stems Cheeks: Jungle cock nail feathers, one each side

Create Your Own Eye

2 The following section shows how to create an eye for a blind eye hook. A blind eye hook was manufactured without an actual eye to which a tippet is attached. Silkworm gut was used to fashion the hook eyes. Today most of fish using hooks with metal eyes, whether they have ringed or return loop eyes. I have not tested the breaking strength of the silk gut available. Shewey, in his book, recommends using braided Dacron backing as the eye material if you are really going to fish a blind eye hook. I included this both for those who actually want to fish blind eye hooks and for those wanting to know for the purpose of tying some blind eye patterns to be framed. Lets begin. Tie in white thread " to 3/8" back from the blind eye. Wrap forward 1/32" to 1/16". Cut 1" of twisted silk gut. It is your choice as to how you want to prepare the gut. The Partridge twisted silk gut is much softer and easier to flatten than the Japanese twisted silk gut. Soak the gut until it becomes as soft and pliable as you desire. Wrap the gut around a bobbin or similarly sized cylinder so that it forms a long U shape. While holding the gut against the bobbin with your left thumb, nick the gut with your right thumb and middle finger, respectively, so the gut bends inward on each side. To thin the gut out, you may chew on the ends to flatten them and/or stagger cut the three strands of the gut once tied onto the hook.

You may leave the hook in the normal upright position or turn the hook upside down when tying in the gut. Begin tying in the far side of the gut first, wrapping forward, and leaving at least 1/8" of bare hook shank exposed. Then tie in the near side, wrapping back toward the hook point.

Everything Aft of the Tail

This hook has a return loop eye. I tie in my thread right where the return loop ends only if I am making a floss or tinsel body. Otherwise any dubbing, yarn, or synthetic braids will usually cover up any bumps where materials are tied in and tied off. I trim my thread tag waste end and wrap edge to edge down the hook shank towards the bend, stopping at a spot right above the hooks point. Turn hook point side up. Tie in a 4" piece of small oval silver tinsel along the left (near) underside of the hook with the smallest waste end possible. Holding the tinsel tightly in your non-dominant hand, wrap the thread rearward down the hook over the tinsel to a point even with the hook point. Keep the tinsel along the underside of the hook, slightly on the left (near side). Let the thread hang.

Take one wrap with the tinsel around bare shank and then over the thread base. Make three or four total wraps. Tie off the tinsel on the underside of the shank with two thread wraps. Wrap over the remaining waste tinsel strand with the thread, keeping the tinsel along the right (far) underside of the shank. Trim the tinsel flush with the tinsel tie in point. In this way I can minimize the amount of waste at the tie in point and have a smooth base for the floss tag. Tie in a 6" section of yellow silk on the underside of the shank. Wrap the silk back edge to edge, and then wrap forward, overlapping each wrap by half. Tie off on the underside of the shank with one or two thread wraps.

Tail, Ribs, and Spey Hackle

Strip or cut off a few schlappen fibers, and tie them in with two or three firm wraps right where the tag ends. You really do not need anymore; it is overkill. Now you have a choice when to clip the tail waste ends: clip now or wrap over them on way to tying in the ribs. You make the choice. For silk and tinsel bodies I clip the tail waste ends. For a thick body, I just wrap thread over the waste ends. Here I clipped them before proceeding. Next, I wrapped the thread edge to edge forward up to the thread tie in point. I turned the hook upside down in the vise. Cut a length of yellow floss, small silver wire, and small oval silver tinsel or twist, each about 2 to 3 times the length of the flys body total. The floss and oval tinsel are merely for decoration. The wire is included for making a stronger fly (see Firming Up the Body). Tie in the ribs with the silver wire along the right underside (far), the yellow floss in the center, and the oval tinsel along the left underside (near) with their ends butting up against the end of the return loop. This way room will be left when finished in front of the flys head for tying a riffle hitch, if so desired. If you do not want that room, tie the ribs in with their butt ends even with the middle of the return loop.

4 Hold the ribs tightly with your non-dominant hand. Wrap the thread over the ribs edge to edge back to the tail.

In this fly, I use natural blue eared pheasant. Other choices include saddle and schlappen hackle, marabou, rhea, pheasant tail strips, and anything else you might imagine. Saddle and schlappen are readily available and dyed in just about any color you want. Some tyers feel these two feathers fibers are not long enough. Others point out these feather fibers rarely foul the fly (wrap around the hook bend, affecting the flys action in the water). You can vary the thickness of the finished hackle by stripping off one side of the hackle or feather used when tying your flies. Marabou, which can be found in any fly shop, has very long and soft fibers. Rhea (and ostrich for that matter) and pheasant tails have been used in Spey flies for at least the last five years. These feathers are similar to marabou but are stiffer. With regard to blue eared pheasant, I enjoy tying with it. However with it being fairly spendy (up to a dollar a feather), I cannot justify stripping off half the feather before wrapping it. My advice is to buy the packages of sized feathers if you are cost conscious. You get feathers that are all approximately the same size. If you are not concerned with having only feathers large enough to wrap a #3/0 long shanked hook, consider splitting an entire blue eared pheasant skin with a few buddies. You will each get several of the large flank feathers and have plenty left to hackle hook sizes #2-6. Use the smaller hackles on large trout wet flies and caddis pupae patterns. The blue eared pheasant is also easy to break when taking that first wrap forward over the body, so be gentle over the first couple of turns. Now rotate the hook back to right side up. When wrapping the thread edge to edge forward, tie in the hackle along the left side of the fly. Normally you would tie in a hackle, like on a woolly bugger, by wrapping towards the tail, not the head. I am doing this to minimize bulk and to keep a smooth base to wrap the body material over. Wrap the thread forward to about the 2/3 1/3 body junction.

Body Work

Tie in a 14 piece of orange floss, and wrap the floss down to the tail and back edge to edge. Tie off the floss and clip the waste. Wrap the thread forward to the middle of the return loop. Tie in a 10 piece of red floss, and wrap the floss down to the end of the orange floss and back. Tie off the floss and clip the waste. You can use whatever you wish for body material on your Spey and Dee flies whether that be floss, dubbing, tinsel, or anything else.

Brightening and Firming Up the Body

Bring the yellow floss rib forward, taking five or six wraps. Tie off and clip the waste. Now bring the oval tinsel or twist forward right behind the floss, along the flosss trailing edge. Tie off and clip the waste end.

Palmer the blue eared pheasant forward right behind the oval or twist. Try to get the stem to butt up against the silver rib. This helps to protect the hackle stem from breaking due to fishing it and fish chewing on it. Bring the small wire up and towards you, wrapping it in the opposite direction than the ribs. Looking from the hook eye down the shank to the tail, the ribs are wound clockwise, so wind the wire counterclockwise. The hackle fibers will get in the way. I place the tip of my bodkin at the point where the wire will cross over both floss and tinsel and then push the fibers away, making room for the wire. By doing this hackle fibers will not get trapped under the wire. And your fly will look better. Tie off and clip the waste wire.

The Long and Short of the Collar

Select a guinea fowl flank feather, and stroke most its fibers from the tip towards the feathers butt end. Only a few fibers should remain at the feathers tip. As this feather stem has an oval profile, it tends to roll when wrapped around the shank. The fibers tend to then flare forwards and backwards. This can be combated by either of two methods. The first is to fold the hackle fibers prior to tying in the feather. Place you hackle pliers on the tip of the feather, and place the loop in the hackle pliers over the hook eye. Pick up your nonserrated scissors and open up the scissors. Place your dominant hand thumb on the near side of the scissors pivot point and place your dominant index finger on the other side of the pivot point. Place the top blades tip on the top edge of the left side of the feather. The angle between the horizontal and a line extending from the blade/feather intersection to your thumb should be about 45 - 60. Then pull and lift up on the feathers butt end with your nondominant hand, putting tension on the feather. Slowly pull the scissor blade toward you. It should take you about 5-10 seconds to go over a 2-3 section of feather. As you pull the blade, the blade should catch each fiber slightly, making a clicking sound, like you would hear dragging your fingernail over the tips of the teeth in a comb. Do not try this on your best feathers at first. Take out your stash of woolly bugger hackle and practice on these feathers first. Tie in the feather by tip on the underside of the hook with the dull side facing the body. Wrap one to three turns, sweeping the hackle fibers back if they do not already lie down. The second method is to fold the fibers back as you wrap the feather. Tie the feather in on the underside of the hook. Clip your hackle pliers on the butt end of the feather. Hold the pliers and take one to three turns with your dominant hand. As you wrap the collar, fold the fibers back with your nondominant hand. I tend to stroke all the fibers back at once and hold onto the fibers as I wrap the collar over the shank to the opposite side of the fly. I then let go. I again stroke back the remaining fibers on the feather, now hanging under the shank of the fly, and take another wrap. Repeat this process until you have as thick a collar as you like.

After tying off the collar on the underside of the shank and trimming off the excess, fold the hackle fibers down and sweep them back. We are doing this to make room for the wing to lie over the top of the body. If some errant fibers will not lie down, clip them off.

Silencing the Tying Fits

Spey and Dee flies use a few different feathers as winging material. Several of the older patterns use bronze mallard. Newer patterns still use it and also use several hackle tips or dyed goose shoulder and turkey tail. Goose shoulder is usually very soft and compresses well. Its fibers max out at around 2 in length. For those who need longer wings, turn to turkey tail. This materials

7 fibers can reach lengths of 4 or more and tends to be stiffer than goose. If you feel adventurous enough to build multicolored wings, marrying two or more sections together, spend some time planning the wing before jumping right in and clipping sections for the wing. Both goose and turkey marry well. Once you get down to very small sections, like three or four fibers in size, I would go with turkey rather than goose for the reason that very small sections of goose are hard to marry. It does not mean that it is impossible, just that you may end up pulling out hair before you finish completely marrying one wing. My description of how to mount the wings on the hook may vary from what you have read, seen, or personally do. Use whatever method you are comfortable with or with which you find success. Do not let that stop you from trying other methods. Once you have selected what you wish to wing your fly with, you must select a matching pair or two of hackles for hackle tip wings or cut matching quill slips. When using quill slip wings, remember the anatomical left side of a feather goes on the fly's left wing, and the anatomical right side of a feather goes on the fly's right wing. This is just a guide. When you clip a section off the stem, notice that there is a taper at the tip end. The fibers closer to the tip end of the feather are usually slightly longer than the fibers closer to the butt end of the feather. When the section is tied in as a wing, the wing will taper, from shortest to longest fibers, from the bottom to the top from a side view and outside to inside from the front or rear view. I happen to like this look best on my Spey flies; however, when I tie my Dee flies, I reverse which section goes on which side. This way when I view the fly from the front, with the wings tied flat in a horizontal plane above the hook shank, and the fibers taper, again shortest to longest, from inside to outside. Something you may have noticed through this tutorial is I have not given any set in stone type of rules. We tie flies mostly similar to the original Spey and Dee flies of the 19th century. Just because some Victorian era Atlantic salmon guides tied flies in a certain way should not keep us from exploring new tying techniques, using new materials, and varying the material components in our flies. I am going to use quill slips from dyed goose shoulders for this flys wing. Again find matched pairs of feathers, primarily to assure you have wing material of about equal length for both sides, or a single center feather. What I mean by center is the fibers on the feather are symmetrical in length. How big of a section should you cut? On these flies I would go with a section that is anywhere between one-half to one-quarter of the width of the hooks gape. On larger hooks, something near half a hook gape may be necessary while on a size 8 or smaller five fibers or less is all you will need. Look on the feather where there are fibers long enough for your wing. Then put your bodkin right next to the feathers stem, and use it to separate the fibers into two parts. Figure out from which of either part you want fibers from. Then use you bodkin again to part adjoining fibers to define the section for your wing. Hold the section up to the fly to see if it is the right size, which is whatever size looks good to you. If the section is too small, gently stroke that section back into the part of the feather you separated the section from (marrying the section back in). Then use you bodkin to define a larger quill slip. I do this so I do not cut the section from the feather only to find it is not large enough for the wing. If the section is too large, use your bodkin to separate a few fibers from either the top or bottom. Marry the excess fibers back into the rest of the feather. Once you have defined the two sections you want, you have the option of either cutting the section from the stem (fibers only) or clipping the stem in two places so the stem remains attached to your section of fibers. If this is the first few flies of this type you have tied, I recommend clipping so the stem remains attached. This way if the wing does not seat properly, when you unwind the thread

8 wraps and take the wing off, the fibers do not fall in two or more sections under the fly and the fibers are much easier to marry back together. In the demonstration fly I will use the fibers without the stem.

How you tie in the wing varies as well. On Spey flies, both sections (left and right) butt up against each other along the top to bottom midline of the fly. Sometimes the wing looks like only one big piece of material was tied, in instead of two. You can do this if you choose, using a single quill slip. This is very effective when using bronze mallard because I find it is easier to even up the tips of the fibers in this material than goose or turkey. Play around with this method and see how you like it. Now on Dee flies, the wings are usually not tied in humped over the body like in Spey flies, but flat in a horizontal plane just above and parallel with the body. From the front view the wing varies from being parallel with body to angling out from the. You can first tie in one section of the wing and then tie in the other section right on top of the first or tie in the wings like on Spey flies where the sections do not overlap each other. It is your choice. I recommend at least trying both. One may appeal more to you. You can tie both sections of the wing in at the same time (like the cheeks, described below) or one at a time. I prefer to tie them in one at time, starting with the far side. My rationale for this is I always have a harder time getting the far side tied correctly than the near side. When I used to tie in the near side first, I could get it positioned properly with little effort. But when I tied in the far wing, I could rarely get it to butt up against the near wing. The far side would often rotate over and under the fly. So I would have to take it off and try again. When I tried to get the far side to sit right, the near wings fibers would often have already split. It was a hassle to marry the near wing back together. So I began tying in the far wing first. I place it slightly over on the near side half of the fly. I would take two soft wraps and then tighten the wraps. As I tightened the thread wraps the wing would slide slightly over to the far side. This way I could get the far side wing positioned exactly where I wanted it. Next, I would take one to three firm wraps and move onto the near side. With my fingers I would hold the near side wing enough towards me so that there was a gap between both wings. After taking two soft wraps and tightening the wraps, the near side wing would slowly rotate over towards the far side wing and come to a stop when it butted up against the far wing. Take two more firm wraps and the wing was done.

So we now have prepared the wing sections, and it is time to put them on. Start with the far wing, placing it slightly past the midline of the fly over on the near side. Take two soft wraps and tighten. When pleased with the set of the wing, take another two or three firm wraps. Position the near side wing just a little towards you, off the midline. Take two soft wraps and tighten. When pleased with the set of the wing, take another two or three firm wraps. Place a drop or two of head cement on the wraps of thread holding the wings in place. Let that dry completely. Trim the waste ends a few fibers at a time. If you trim all of the waste ends off in one or two cuts, the wing fibers are more likely to shift.

The Pretty, Final Parts

After the wing, Spey and Dee flies do not require much more to add. That should not inhibit you from adding whatever suits your whim. A few of the fancier and more dressed up patterns use jungle cock as cheeks, laying at the base of the wing or drooping below the shank in front of the collar, and add a golden pheasant crest or two, natural or dyed, over the wing. Some of the wings constructed of multiple feathers (to create a layered look) use progressively shorter and varying colors for a standout wing also have small, colorful cheeks. In this fly, I have gone with a pair of drooping jungle cock feathers. Turn hook upside down in the vise. Of the presorted ten packs of feathers, use large for hook sizes 1/0 or larger, medium for 1 down to 8, and small on anything smaller than 8. This is just a guide, as you are free to put big eyes on a small fly and small eyes on a large fly. I strip off all of the fibers down from the small, often oval shaped, white spot on the feather. This way the small waxy-like spot gives my thread more to grip when I tie in as the small waxy-like spot is wider than the feathers stem. That may not mean much, but the head by this point is usually shaped like a small ice cream cone (cylindrical cone). When I place a wrap or two of thread over the small white spot, the white spot conforms to the shape of the

10 head (convex) and can cause a slight bow to the rest of the feather. This in effect prevents the jungle cock feather from sticking out from the fly as most of the feather is slightly to moderately conforming to the shape of the front of the fly. It is almost as though the jungle cock gets sucked into the body. You can tie the feathers in one at a time or both at the same time. I choose to tie them in one at a time. I have had more success getting one side set and then setting the the other side than getting both to seat properly in one step. Place the now nearside (left side) feather at about 45 above the shank when viewed from the front and resting slightly on the fibers of the collar. Make one or two soft wraps, and check the position of the feather. If you like where it sits, take another one to three firm wraps.

If you chose to set both at the same time, lick the thumb and middle finger of your nondominant hand. Touch your moistened thumb to the near side cheek and your moistened middle finger to the far side cheek. The saliva is tacky enough to hold both at the same time, and you have to gently place your fingers and hence the cheeks where you want them. Take two wraps of thread and, with some luck and skill, the cheeks should be in their respective correct positions. Take one to three firm wraps to finish seating the feathers. This trick was shown to me by Rich Youngers of Salem, Oregon. Clip the waste ends of the cheek feathers, take enough wraps to shape the head how you like it, usually three to five wraps for a really small wrap or eight to fifteen for a larger head. Whip finish, clip the thread, and finish off with head cement. Congratulations on tying a Spey/Dee fly!

11

Further Reading

Helvie, H. Kent. (1994). Steelhead Fly Tying Guide. Frank Amato Publications: Portland, OR. Shewey, John. (2002). Spey Flies & Dee Flies: Their History & Construction. Frank Amato Publications: Portland, OR. Veverka, Bob. (2005). Spey Flies and How to Tie Them. Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA. For a look at what most of these flies looked liked when tied and fished for the first time on this side of the pond, check out Trey Combs books on steelhead fly fishing. His first, Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies (1976), has some nice photos. His second, Steelhead Fly Fishing (1991), has more. These cover the ties before they really caught on and tyers were whipping out fanciful patterns using every color under the rainbow and just about any feather possible. I am not criticizing the newer ties. The older flies were primarily meant to be fished, not viewed at a Greenwich Village gallery. The newer ties I see posted on the web and in magazine articles keep getting better and better. Keep an eye out in current fly magazines. Every once in a while, a spey article gets published, most likely to be found in Fly Tyer magazine and the last few pages of Northwest Fly Fisher. As an aside, Veverkas text should be readily obtainable through any fly shop or on any online bookseller. Both Shewey and Hevlies books can be found in their softcover format, but the hardcovers are hard to come by. I think there were only 1000 hardcovers printed of Sheweys and I do not know how many of Helvies. If you really want a hardcover of any of the books I have mentioned, first check out your local fly shop. Let your local fly shop proprietors know you would like a copy and maybe through connections can find you one. If they are without, time to check the web. I would first look at Amazon or Barnes and Noble. If nothing pans out on Barnes and Noble, click on their search other sellers (usually on the lower right). Sometimes I have found books this way that I had found nowhere else. If you get a second strike, I would check out Abebooks (www.abebooks.com). I personally have ordered over fifty books, not all fishing, through this website and have had no problem in my four years of using it. If Abebooks does not have it, I doubt you will find it anywhere else online. Go back and check once a week. You may be surprised. You can look at Alibris (www.alibris.com) or Bookfinder (www.bookfinder.com). As a last resort, ask around your local fly fishing club/group. For those of you who like to peruse the net, here are some sites I enjoy to check often: Salmonfly.net (www.angelfire.com/wa/salmonid/) has plenty of tyers and patterns to keep you drooling into next month. FlyTyingForum (www.flytyingforum.com) has daily submissions to their pattern database, so check out the Salmon and Steelhead section. Though many of the posts are of classic Atlantic salmon patterns, there are plenty of speys to keep you looking for more. A Catalog of Spey and Dee Flies (www.elilabs.com/~rj/fishing/flies/spey/title_page.html) has very nice close-ups of a variety of ties. Two clicks to the upper left of the site should send you to the pattern gallery.

12

John McLains site (www.feathersmc.com) and www.bas4sure.com have some speys lurking in all the Atlantic salmon flies. Please place a pillow in your lap before looking at these two sites. I recommend this to prevent an injury to your jaw dropping when you see these flies. Gerald Bartsch has a nice page (http://qualityflies.com/dir/1.html) of spey flies he sells. It is worth a look. If you want to purely look at flies, check out this boards forum and gallery of individual patterns and swaps, as well as the FlyFishing Forum board (http://www.flyfishingforum.com/flytalk4/index.php) under Salmon and Steelhead. There are usually daily to weekly posts by someone showing off his or her latest creation or asking for a critique. Those are all of the sites and books I can dig up right now off the top of my head. If I were home back in Oregon, I would give you a longer list, including magazine articles (school in New York is taking precedence). One last mentionable is I have done one tying tutorial prior to this one. The step by step was done for a class I led last year on how to tie a particular classic Atlantic salmon fly. If you are interested in reading it, just follow the link (http://www.feathersmc.com/articles.php?ID=56).

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Favorite Flies and Their HistoriesDocument719 pagesFavorite Flies and Their HistoriesEuclides Rezende100% (1)

- OPST Tips ExplainedDocument4 pagesOPST Tips Explainedfergot2010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tenkara Kebari - Pattern Classification: © 2010 Yoshikazu Fujioka (Update 2015)Document2 pagesTenkara Kebari - Pattern Classification: © 2010 Yoshikazu Fujioka (Update 2015)Andrew BenavidesPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Spey Lines 2010Document13 pagesUnderstanding Spey Lines 2010lengyianchua206Pas encore d'évaluation

- TWO-PERSON AVALANCHE STEPS BOXING SET - Brennan TranslationDocument62 pagesTWO-PERSON AVALANCHE STEPS BOXING SET - Brennan TranslationPauloCésarPas encore d'évaluation

- Floating Flies and How To Dress Them by Frederick M. Halford 1885Document208 pagesFloating Flies and How To Dress Them by Frederick M. Halford 1885Leena Rogers100% (1)

- Fly Tying Guide 7-6-2015Document313 pagesFly Tying Guide 7-6-2015gambito rabioso100% (1)

- Thomas R Bender A California Knife MakerDocument6 pagesThomas R Bender A California Knife MakerTwobirds Flying PublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Bush PigDocument2 pagesBush Piglengyianchua206100% (1)

- Fly FishingDocument161 pagesFly FishingPedro Pérez100% (2)

- How To Make BellowsDocument5 pagesHow To Make BellowsBarry Wood100% (1)

- The Handsewn SpritslDocument16 pagesThe Handsewn SpritsllocksafePas encore d'évaluation

- Build A Scale To Weigh Bee HivesDocument8 pagesBuild A Scale To Weigh Bee HivesPopescuAlexandruIonPas encore d'évaluation

- Denier - Size of Fly Tying ThreadDocument4 pagesDenier - Size of Fly Tying ThreadSaša MinićPas encore d'évaluation

- Carter, W. - Nymphing From Novice To ExpertDocument18 pagesCarter, W. - Nymphing From Novice To ExpertAnízio Luiz Freitas de Mesquita100% (1)

- CZN Catalogue 2010Document45 pagesCZN Catalogue 2010odin_auerPas encore d'évaluation

- All About TenkaraDocument4 pagesAll About TenkaraAnízio Luiz Freitas de MesquitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hummus OttolenghiDocument2 pagesHummus Ottolenghilibroschefs15Pas encore d'évaluation

- Making A Flemish BowstringDocument22 pagesMaking A Flemish BowstringKendo El SalvadorPas encore d'évaluation

- Mustad HooksDocument3 pagesMustad Hooksrazvan_mateiPas encore d'évaluation

- Fly Tying Made Clear and SimpleDocument15 pagesFly Tying Made Clear and Simplecarlosdegoycoechea0% (1)

- Fishing Clark SpoonsDocument16 pagesFishing Clark SpoonsJacobo OrtizPas encore d'évaluation

- Fire - Bow DrillDocument6 pagesFire - Bow DrillhalonearthPas encore d'évaluation

- Kumajiro's Fly Box - What Is-It With Tenkara FishingDocument7 pagesKumajiro's Fly Box - What Is-It With Tenkara FishingAnízio Luiz Freitas de MesquitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bow Strings Pedro SerralheiroDocument9 pagesBow Strings Pedro SerralheiroRui Manuel RomãoPas encore d'évaluation

- The North Woods PaddleDocument8 pagesThe North Woods PaddletwinscrewcanoePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Make Improvised Tools Peace Corp 1980Document57 pagesHow To Make Improvised Tools Peace Corp 1980John J Johnson JrPas encore d'évaluation

- Mini Jump Frog by - Rfs FishingDocument1 pageMini Jump Frog by - Rfs FishingARIS MUNANDARPas encore d'évaluation

- Partridge 2008Document36 pagesPartridge 2008Carlos Urrutia100% (2)

- Fishy's Hopper Pattern - Fly Fishing & Fly Tying Information ResourceDocument7 pagesFishy's Hopper Pattern - Fly Fishing & Fly Tying Information ResourceVarga IosifPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Plank The Hull of A Sharp Bow Model ShipDocument22 pagesHow To Plank The Hull of A Sharp Bow Model Shiproman5791100% (2)

- Root Coverage PDFDocument24 pagesRoot Coverage PDFJason Pak100% (1)

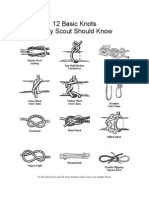

- Knots TechniquesDocument2 pagesKnots TechniquesFirman Rafif RaniPas encore d'évaluation

- CRKT's Yukanto A James Williams DesignDocument4 pagesCRKT's Yukanto A James Williams DesignTwobirds Flying PublicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Fly Tying Manual: Getting StartedDocument8 pagesBasic Fly Tying Manual: Getting StartedRio Vasallo100% (1)

- Electrolytic Rust Removal PDFDocument4 pagesElectrolytic Rust Removal PDFCarlos SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Climbing KnotsDocument5 pagesBasic Climbing Knotscallcott2006Pas encore d'évaluation

- Project 3 - Fabricated Mokume Band - Steven JacobDocument1 pageProject 3 - Fabricated Mokume Band - Steven Jacobmajope1966Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adirondack Beach Chair W 2 Positions PDFDocument15 pagesAdirondack Beach Chair W 2 Positions PDFNana Obiri Yeboa Darko100% (1)

- Taylor Sanders, ProtozoaDocument54 pagesTaylor Sanders, ProtozoaAxelWarnerPas encore d'évaluation

- Thick Free Gingival and Connective Tissue Autografts For Root Coverage.Document8 pagesThick Free Gingival and Connective Tissue Autografts For Root Coverage.Mathew UsfPas encore d'évaluation

- 21: Bone Wound Healing and OsseointegrationDocument15 pages21: Bone Wound Healing and OsseointegrationNYUCD17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sorting Machine For ShrimpDocument11 pagesSorting Machine For ShrimpPhạm Văn LượngPas encore d'évaluation

- Redwood CanoeDocument6 pagesRedwood Canoeb0beiiiPas encore d'évaluation

- Carl Church Bird Taxidermy - Breakthrough Magazine Issue 89Document4 pagesCarl Church Bird Taxidermy - Breakthrough Magazine Issue 89rebootisPas encore d'évaluation

- Materials:: Geoff Burke L.L.BeanDocument4 pagesMaterials:: Geoff Burke L.L.BeantwinscrewcanoePas encore d'évaluation

- Sail - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument8 pagesSail - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediad_richard_dPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure PDFDocument12 pagesBrochure PDFdonguiePas encore d'évaluation

- Zebco Europe Mustad Catalogue 2013Document21 pagesZebco Europe Mustad Catalogue 2013Martin ByrnePas encore d'évaluation

- Trout Fishing and The Color of Wet DubbingDocument6 pagesTrout Fishing and The Color of Wet DubbingMichael Lang100% (3)

- Build A Greenland Kayak Part 2Document12 pagesBuild A Greenland Kayak Part 2manoel souza100% (1)

- The Complete AnglerDocument333 pagesThe Complete AnglerEduardo Castellanos100% (1)

- Wing Paddles TheoryDocument4 pagesWing Paddles TheoryboerfrancPas encore d'évaluation

- Ishimura, M. & Kelleher, K. C. - Tenkara, Radically Simple, Ultralight Fly FishingDocument163 pagesIshimura, M. & Kelleher, K. C. - Tenkara, Radically Simple, Ultralight Fly FishingAnízio Luiz Freitas de MesquitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Three Sided Lidded Box: Woodturning ADocument11 pagesThree Sided Lidded Box: Woodturning AGustavo RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- The Technology of Fly RodsDocument117 pagesThe Technology of Fly RodsNyocko Neta100% (1)

- Fly Fishing Basic SetupDocument8 pagesFly Fishing Basic SetupVop MirPas encore d'évaluation

- 8 Strand Tuck SpliceDocument2 pages8 Strand Tuck SpliceDelando CoriahPas encore d'évaluation

- Exercise:: 2019 JanuaryDocument21 pagesExercise:: 2019 JanuaryjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Mental SwordplayDocument1 pageMental SwordplayjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Tracing Complexity TheoryDocument25 pagesTracing Complexity TheoryjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Thoughts On Scale': by Jack FargnoliDocument2 pagesThoughts On Scale': by Jack FargnolijfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- "Morning" Eventually Everything Comes Down To Coffee, Eggs, Scrambled, A Preference For Whole Wheat. Proud, Pure, Perfect, On A Plain White PlateDocument1 page"Morning" Eventually Everything Comes Down To Coffee, Eggs, Scrambled, A Preference For Whole Wheat. Proud, Pure, Perfect, On A Plain White PlatejfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Hannah Arendt's Encounter With MannheimDocument65 pagesHannah Arendt's Encounter With MannheimjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- BIBLIOGRAPHY - Project GutenbergDocument281 pagesBIBLIOGRAPHY - Project GutenbergjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Baking Artisan Bread - Ciril HitzDocument227 pagesBaking Artisan Bread - Ciril Hitzerwinv97% (30)

- Foucault and Deleuze - Making A Difference With NietzscheDocument18 pagesFoucault and Deleuze - Making A Difference With NietzschejfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- KERN, Stephen - The Culture of Time and SpaceDocument58 pagesKERN, Stephen - The Culture of Time and SpaceDiogo LiberanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tweed Salmon FishingDocument328 pagesTweed Salmon Fishingjfargnoli100% (1)

- A Non-Aristotelian Study of PhilosophyDocument60 pagesA Non-Aristotelian Study of PhilosophyjfargnoliPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian HistoryDocument8 pagesIndian HistoryKarthickeyan BangaruPas encore d'évaluation

- Chain Saw: Identify Carpentry Power Tools and Their UsageDocument3 pagesChain Saw: Identify Carpentry Power Tools and Their UsageJc SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction: Popular Music and The Moving Image in Eastern EuropeDocument25 pagesIntroduction: Popular Music and The Moving Image in Eastern EuropeДарья ЖурковаPas encore d'évaluation

- My Dad & Me (En)Document3 pagesMy Dad & Me (En)Fast Net Cafe60% (5)

- Cadet Field ManualDocument252 pagesCadet Field Manualapi-439996676Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction PaperDocument4 pagesReaction PaperJoan-na may MontañoPas encore d'évaluation

- Promise Kept For John Anderson's Biggest Fan, His DaughterDocument3 pagesPromise Kept For John Anderson's Biggest Fan, His DaughterDaniel HousePas encore d'évaluation

- TH THDocument6 pagesTH THSamiksha JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Bluestone Alley LTR NoteDocument2 pagesBluestone Alley LTR NoteArvin John Masuela88% (8)

- Kim Lighting WTC Wide Throw Cutoff Brochure 1976Document24 pagesKim Lighting WTC Wide Throw Cutoff Brochure 1976Alan MastersPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Sigil MagicDocument130 pagesBasic Sigil Magicrobotmagician93% (44)

- 0500 m19 in 12Document4 pages0500 m19 in 12Cristian Sneider Granados CárdenasPas encore d'évaluation

- Linea de Tiempo ShakiraDocument2 pagesLinea de Tiempo ShakiraAndres F Patiño SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Hair Love Worksheet Around The Short Movie and The Picture Stories Worksheet Templates Layouts Writin - 132644Document9 pagesHair Love Worksheet Around The Short Movie and The Picture Stories Worksheet Templates Layouts Writin - 132644yuliaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1928 Clymer RosicruciansDocument48 pages1928 Clymer RosicruciansTóthné Mónika100% (2)

- NarratorDocument3 pagesNarratorOana OlaruPas encore d'évaluation

- American TranscendentalismDocument18 pagesAmerican Transcendentalismhatis100% (1)

- Midterm Exam...Document4 pagesMidterm Exam...Lhine KiwalanPas encore d'évaluation

- USA - Augusta Read ThomasDocument2 pagesUSA - Augusta Read ThomasEtnoalbanianPas encore d'évaluation

- Examination of ConscienceDocument2 pagesExamination of Consciencetonos8783Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Misterious Power of Xingyi QuanDocument353 pagesThe Misterious Power of Xingyi Quannajwa latifah96% (27)

- New Covenant Theology and Futuristic PremillennialismDocument12 pagesNew Covenant Theology and Futuristic Premillennialismsizquier66Pas encore d'évaluation

- List of Seinfeld EpisodesDocument18 pagesList of Seinfeld EpisodestusarPas encore d'évaluation

- Nisha - Life After MarriageDocument292 pagesNisha - Life After Marriageshaikh rizwan100% (1)

- English Brief Guide To Hajj PDFDocument1 pageEnglish Brief Guide To Hajj PDFAbu Saleh MusaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic FactsDocument3 pagesBasic FactsAustrian National Tourism BoardPas encore d'évaluation

- NP ArocoatDocument4 pagesNP ArocoatJohn HaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Shall We Do With The Drunken SailorDocument24 pagesWhat Shall We Do With The Drunken SailorMike HatchardPas encore d'évaluation

- Old Yeller by Fred Gipson - Teacher Study GuideDocument3 pagesOld Yeller by Fred Gipson - Teacher Study GuideHarperAcademic67% (3)

- Artpreneur Course OutlineDocument6 pagesArtpreneur Course OutlineAdithyan Gowtham0% (1)

- Edward's Menagerie New Edition: Over 50 easy-to-make soft toy animal crochet patternsD'EverandEdward's Menagerie New Edition: Over 50 easy-to-make soft toy animal crochet patternsPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasure Bookmaking: Crafting Handmade Sustainable JournalsD'EverandTreasure Bookmaking: Crafting Handmade Sustainable JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- House Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetD'EverandHouse Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetPas encore d'évaluation

- Crochet Zodiac Dolls: Stitch the horoscope with astrological amigurumiD'EverandCrochet Zodiac Dolls: Stitch the horoscope with astrological amigurumiÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (3)

- 100 Micro Amigurumi: Crochet patterns and charts for tiny amigurumiD'Everand100 Micro Amigurumi: Crochet patterns and charts for tiny amigurumiÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Swatch This, 3000+ Color Palettes for Success: Perfect for Artists, Designers, MakersD'EverandSwatch This, 3000+ Color Palettes for Success: Perfect for Artists, Designers, MakersÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (3)

- Crochet Pattern Books: The Ultimate Complete Guide to Learning How to Crochet FastD'EverandCrochet Pattern Books: The Ultimate Complete Guide to Learning How to Crochet FastÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Edward's Menagerie: Dogs: 50 canine crochet patternsD'EverandEdward's Menagerie: Dogs: 50 canine crochet patternsÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (5)

- The Martha Manual: How to Do (Almost) EverythingD'EverandThe Martha Manual: How to Do (Almost) EverythingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (11)

- Crochet Creatures of Myth and Legend: 19 Designs Easy Cute Critters to Legendary BeastsD'EverandCrochet Creatures of Myth and Legend: 19 Designs Easy Cute Critters to Legendary BeastsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (10)

- 100 Crochet Tiles: Charts and patterns for crochet motifs inspired by decorative tilesD'Everand100 Crochet Tiles: Charts and patterns for crochet motifs inspired by decorative tilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Crochet in a Weekend: 29 Quick-to-Stitch Sweaters, Tops, Shawls & MoreD'EverandCrochet in a Weekend: 29 Quick-to-Stitch Sweaters, Tops, Shawls & MoreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- Modern Crochet Style: 15 Colourful Crochet Patterns For You and Your HomeD'EverandModern Crochet Style: 15 Colourful Crochet Patterns For You and Your HomeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Crochet Impkins: Over a million possible combinations! Yes, really!D'EverandCrochet Impkins: Over a million possible combinations! Yes, really!Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (10)

- Amigurumi Cats: Crochet Sweet Kitties the Japanese Way (24 Projects of Cats to Crochet)D'EverandAmigurumi Cats: Crochet Sweet Kitties the Japanese Way (24 Projects of Cats to Crochet)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hello Hexie!: 20 Easy Crochet Patterns from Simple Granny HexagonsD'EverandHello Hexie!: 20 Easy Crochet Patterns from Simple Granny HexagonsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Crochet Iconic Women: Amigurumi Patterns for 15 Women Who Changed the WorldD'EverandCrochet Iconic Women: Amigurumi Patterns for 15 Women Who Changed the WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (30)

- The Fellowship of the Knits: Lord of the Rings: The Unofficial Knitting BookD'EverandThe Fellowship of the Knits: Lord of the Rings: The Unofficial Knitting BookÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Textiles Transformed: Thread and thrift with reclaimed textilesD'EverandTextiles Transformed: Thread and thrift with reclaimed textilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Colorful Crochet Knitwear: Crochet sweaters and more with mosaic, intarsia and tapestry crochet patternsD'EverandColorful Crochet Knitwear: Crochet sweaters and more with mosaic, intarsia and tapestry crochet patternsPas encore d'évaluation

- Edward's Menagerie: Over 40 Soft and Snuggly Toy Animal Crochet PatternsD'EverandEdward's Menagerie: Over 40 Soft and Snuggly Toy Animal Crochet PatternsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (10)

- Modern Crochet Sweaters: 20 Chic Designs for Everyday WearD'EverandModern Crochet Sweaters: 20 Chic Designs for Everyday WearÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Upcycling: 20 Creative Projects Made from Reclaimed MaterialsD'EverandUpcycling: 20 Creative Projects Made from Reclaimed MaterialsPas encore d'évaluation

- Fairytale Blankets to Crochet: 10 Fantasy-Themed Children's Blankets for Storytime CuddlesD'EverandFairytale Blankets to Crochet: 10 Fantasy-Themed Children's Blankets for Storytime CuddlesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Build Your Skills Crochet Tops: 26 Simple Patterns for First-Time Sweaters, Shrugs, Ponchos & MoreD'EverandBuild Your Skills Crochet Tops: 26 Simple Patterns for First-Time Sweaters, Shrugs, Ponchos & MoreÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- Radical Sewing: Pattern-Free, Sustainable Fashions for All BodiesD'EverandRadical Sewing: Pattern-Free, Sustainable Fashions for All BodiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Creative Polymer Clay: Over 30 Techniques and Projects for Contemporary Wearable ArtD'EverandCreative Polymer Clay: Over 30 Techniques and Projects for Contemporary Wearable ArtPas encore d'évaluation