Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

What Is Logic

Transféré par

Muhammad FarhanDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

What Is Logic

Transféré par

Muhammad FarhanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

What is logic?

Logic encompasses many different kinds of study, so that one might wonder what the common thread is. Some claim that logic is the study of truth, and is thus the most basic and fundamental science. While every science aims at truth, logic is the science of truth itself. It tries to discover the truth about truth. Logic studies truth in the same way that biology studies living things. Others say that logic is concerned with thought, and tries to discover the laws of thought. These laws do not describe the way people actually think, for that is the task of psychology. Rather, they prescribe the way people ought to think; they describe the way a perfect mind thinks. Logic is like ethics and morality, in that it separates right from wrong. Logic, one might say, is the ethics of thought and belief. Others say that logic is essentially concerned with language, in some way. Logic tries to understand the logical form of statements, and certain structural relations between sentences. It is certainly true that logicians spend a lot of time studying languages, especially the artificial languages that logicians themselves have devised. Much of this course will consist of learning how to use artificial languages. Logicians also study natural languages, such as English, French, Mandarin and so on. In my view, logic is concerned with all three of these, with thought, with language, and with truth. This is possible, since these three things are closely connected. But how? This is a controversial area in philosophy, which we shall explore a little.

Deduction and Induction

In logic, there are two distinct methods of reasoning namely the deductive and the inductive approaches.

Deductive Reasoning works from the "general" to the "specific". This is also called a "topdown" approach. The deductive reasoning works as follows: think of a theory about topic and then narrow it down to specific hypothesis (hypothesis that we test or can test). Narrow down further if we would like to collect observations for hypothesis (note that we collect observations to accept or reject hypothesis and the reason we do that is to confirm or refute our original theory). In a conclusion, when we use deduction we reason from general principles to specific cases, as in applying a mathematical theorem to a particular problem or in citing a law of physics to predict the outcome of an experiment. Theory Hypothesis Observation Confirmation Deduction Reasoning Theory Hypothesis Pattern Observation Induction Reasoning

An Inductive Reasoning works the other way around, it works from observation (or

observations) works toward generalizations and theories. This is also called a bottom-up approach. Inductive reason starts from specific observations (or measurement if you are mathematician or more precisely statistician), look for patterns (or no patterns), regularities (or irregularities), formulate hypothesis that we could work with and finally ended up developing general theories or drawing conclusion. Note that that is how Newton reached to "Law of Gravitation" from "apple and his head observation"). In a conclusion, when we use Induction we observe a number of specific instances and from them infer a general principle or law.

These two methods are sense very different in nature when use in conducting researches other than being top-down and bottom-up. Inductive reasoning is open-ended and exploratory especially at the beginning. On the other hand, deductive reasoning is narrow in nature and is concerned with testing or confirming hypothesis. You may already notice that we could merge these two approaches into one circular pattern from theory to observations and again form observation to theory. When we say some researcher (Einstein) develops a new theory (relativity) we usually mean that he observes some pattern in the data (light).

COMPARISON OF TWO REASONING

Properties of Deduction

In a valid deductive argument, all of the content of the conclusion is present, at least implicitly, in the premises. Deduction is nonampliative.

If the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. Valid deduction is necessarily truth preserving.

If new premises are added to a valid deductive argument (and none of its premises are changed or deleted) the argument remains valid.

Deduction is erosion-proof. Deductive validity is an all-or-nothing matter; validity does not come in degrees. An argument is totally valid, or it is invalid.

Properties of Induction

Induction is ampliative. The conclusion of an inductive argument has content that goes beyond the content of its premises. A correct inductive argument may have true premises and a false conclusion. Induction is not necessarily truth preserving.

New premises may completely undermine a strong inductive argument. Induction is not erosion-proof.

Inductive arguments come in different degrees of strength. In some inductions, the premises support the conclusions more strongly than in others.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Naveed and ButtDocument5 pagesNaveed and ButtMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Desi Efu ReportDocument66 pagesDesi Efu ReportMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Socio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasDocument3 pagesSocio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Muhammad Abdul RaufDocument1 pageMuhammad Abdul RaufMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Socio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanDocument3 pagesSocio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of RamadanDocument4 pagesImportance of RamadanMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- To Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Document1 pageTo Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Muhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Rosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesRosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Title Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsDocument4 pagesTitle Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank of Punjab: Internship Report ONDocument7 pagesBank of Punjab: Internship Report ONMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 2Document23 pagesGroup 2Muhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Govt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateDocument1 pageGovt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDocument4 pagesChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDocument4 pagesChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityDocument1 pageLazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Muhammad Faisal HanifDocument2 pagesMuhammad Faisal HanifMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

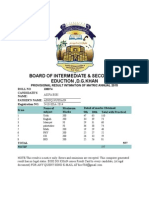

- Board of Intermediate & Secondary Eduction, D.G.KhanDocument1 pageBoard of Intermediate & Secondary Eduction, D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Vitae Ghulam Qamber Tariq: ObjectivesDocument1 pageCurriculum Vitae Ghulam Qamber Tariq: ObjectivesMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityDocument1 pageSajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Muhammad Tahir: Degree Passing Year Marks Board/ UniversityDocument2 pagesMuhammad Tahir: Degree Passing Year Marks Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- ZoologyDocument12 pagesZoologyMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- By Shumaila Raza B.A (B.Z.U)Document8 pagesBy Shumaila Raza B.A (B.Z.U)Muhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Waft Helper School, D.G.Khan: 1 TERM 2013Document4 pagesThe Waft Helper School, D.G.Khan: 1 TERM 2013Muhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic: Socio-Economic Causes of Suicide in D.G.Khan QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesTopic: Socio-Economic Causes of Suicide in D.G.Khan QuestionnaireMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Alfalah NGO - DocfsdaDocument53 pagesAlfalah NGO - DocfsdaMuhammad FarhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Angle Chase As PDFDocument7 pagesAngle Chase As PDFNM HCDEPas encore d'évaluation

- Modeling of Reinforced Concrete BeamDocument28 pagesModeling of Reinforced Concrete BeamNGUYEN89% (27)

- QT 5 Inferential Chi SquareDocument23 pagesQT 5 Inferential Chi SquareSaad MasoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 4 Positioining V2Document39 pagesTopic 4 Positioining V2Aqilah Taufik100% (2)

- Cbse - Department of Skill Education Curriculum For Session 2021-2022Document13 pagesCbse - Department of Skill Education Curriculum For Session 2021-2022Dushyant SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Stability and Stable Production Limit of An Oil WellDocument15 pagesStability and Stable Production Limit of An Oil WellNwakile ChukwuebukaPas encore d'évaluation

- Metoda Securiti Pada DNP3 ProtokolDocument16 pagesMetoda Securiti Pada DNP3 ProtokolDeny AriefPas encore d'évaluation

- SMAC Actuators User ManualDocument52 pagesSMAC Actuators User ManualGabo DuarPas encore d'évaluation

- Solutions and Solubility 2021Document3 pagesSolutions and Solubility 2021Mauro De LollisPas encore d'évaluation

- Java Programming For BSC It 4th Sem Kuvempu UniversityDocument52 pagesJava Programming For BSC It 4th Sem Kuvempu UniversityUsha Shaw100% (1)

- Topic 4Document23 pagesTopic 4Joe HanPas encore d'évaluation

- 10K Ductile Cast Iron Gate Valve (Flange Type) TOYO VALVE Gate ValvesDocument4 pages10K Ductile Cast Iron Gate Valve (Flange Type) TOYO VALVE Gate ValvesFredie LabradorPas encore d'évaluation

- 9011 VW Rebar Strainmeter (E)Document2 pages9011 VW Rebar Strainmeter (E)JasonPas encore d'évaluation

- PDS Example Collection 24-01-11 - Open PDFDocument52 pagesPDS Example Collection 24-01-11 - Open PDFMichael GarrisonPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 Drawer RunnersDocument20 pages07 Drawer RunnersngotiensiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2009 06 02 Library-Cache-LockDocument9 pages2009 06 02 Library-Cache-LockAbdul WahabPas encore d'évaluation

- Geomembrane Liner Installation AtarfilDocument24 pagesGeomembrane Liner Installation Atarfildavid1173Pas encore d'évaluation

- TIMSS Booklet 1Document11 pagesTIMSS Booklet 1Hrid 2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hypothesis Testing in Stata PDFDocument9 pagesHypothesis Testing in Stata PDFMarisela FuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- Fuse Link KDocument6 pagesFuse Link KABam BambumPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Capacitors ExplainedDocument16 pagesTypes of Capacitors Explainedarnoldo3551Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Predicting Roller Milling Performance Part II. The Breakage FunctionDocument13 pagesOn Predicting Roller Milling Performance Part II. The Breakage FunctionKenneth AdamsPas encore d'évaluation

- ECG553 Week 10-11 Deep Foundation PileDocument132 pagesECG553 Week 10-11 Deep Foundation PileNUR FATIN SYAHIRAH MOHD AZLIPas encore d'évaluation

- A Quick Route To Sums of PowersDocument6 pagesA Quick Route To Sums of PowersJason WongPas encore d'évaluation

- Summative Test Ist (2nd G)Document2 pagesSummative Test Ist (2nd G)Rosell CabalzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Linear Motion4Document9 pagesLinear Motion4Jai GaizinPas encore d'évaluation

- IR SensorDocument9 pagesIR Sensorujjwal sahaPas encore d'évaluation

- Detergents (Anionic Surfactants, MBAS)Document1 pageDetergents (Anionic Surfactants, MBAS)Anggun SaputriPas encore d'évaluation

- Excel FunctionsDocument13 pagesExcel Functionsfhlim2069Pas encore d'évaluation

- Matrix Stiffness Method EnglishDocument14 pagesMatrix Stiffness Method Englishsteam2021Pas encore d'évaluation