Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Focus On Discipline - Eventing

Transféré par

freak009Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Focus On Discipline - Eventing

Transféré par

freak009Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Focus On Discipline: Eventing

by Charlene Strickland, from The Horse, updated by Dr. Claudia Barton The French call it the concours complet, or the complete test. Eventing questions the mental and physical qualities of horse and rider as the pair perform in the ring and across the landscape. Classically, eventing covers three phases: dressage, speed and endurance over fences, and stadium jumping. The sport's focus is the cross-country: the horse gallops at speed through an equestrian marathon and jumps high and wide fences. At the Olympic and World Championship levels, the discipline challenges the horse to the limits of his skill and strength. These horses work harder and longer than the other two Olympic disciplines (jumping alone or dressage alone), and running and jumping at speed have injured and killed human and equine participants. Veterinarians, officials, riders, and coaches have joined forces to make eventing safer, yet still exhilarating. Levels of Eventing As a sport, eventing traces to Europe's cavalry. Officers competed their chargers to prove the horses' mettle. Whatever the rider commanded, the horse had to perform its best, then snap back for the next day's maneuvers or long marches. From its military origins, the discipline developed in the early 20th Century. Formerly called The Military or the Three-Day Event, the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) has officially named this sport eventing. Its name was once combined training in the U.S., but this country has also changed the name to eventing. The sport is run under the rules and organization of the United States Eventing Association under the umbrella of the United States Equestrian Federation. Riders compete at a range of levels, with demands adjusted to the horse's abilities. Youngsters of the U.S. Pony Club compete in rallies; USEA-recognized events follow five progressively strenuous levels specified by USEF. Horses of average jumping ability might remain in Novice and Training. The longer distance, faster speed, and bigger obstacles of Preliminary make it a milestone between the simpler tests and the tougher requirements of Intermediate and Advanced. In the United States, most eventing competitions are horse trials. A horse trial usually runs two days; an event is usually a two-day or three-day competition. In both, dressage tests the horse's balanced movement, obedience, and response to the rider, while the jumping tests prove the horse's bravery, energy, suppleness, and willingness. The length, speed, and complexity of the cross-country differentiate a horse trial from an event. In either competition, horses face obstacles that might incorporate ditches, narrow width jumps, water, banks (small hills), and drop fences (where the horse has to leap down). Riders aim to finish all segments with a low score or total penalty points. Ideally, they finish with only the initial score awarded in the dressage test. Dressage can decide the placings, as the seasoned riders plan to start out with a low score and not add any

points. To succeed, the horse completes the cross country test by jumping cleanly and within the time limit. The final placement, made with results of stadium jumping, can adjust the placings up or down. To Gallop and Jump The contrast among the event's tests requires a versatile equine athlete. Riders seek to master all three disciplines, although event horses most often excel in one. Eventing isn't restricted by breed, but Thoroughbreds, Thoroughbred crosses, and Irish Sport Horses (ISH) dominate. As demands increase in speed and endurance, these horses prove their "bottom," or the stamina to finish even when they're tired. Joseph O'Dea, DVM, has 52 years in the sport. "You need a physically efficient horse, a horse with talent. He has to be able to use everything he owns. The Thoroughbred has an innate ability to call upon his endocrine system in competition, to shift into that anaerobic metabolism. He just won't give up. When the tank is empty, he finds more and he goes on." O'Dea has worked with the nation's legendary event competitors, as the U.S. Equestrian Team's (USET) head veterinarian beginning in 1956. He named the AngloConnemara cross as a tough athlete, along with the Selle Francais. "Look for a horse that's close-knit and flinty, one that doesn't carry a lot of adipose tissue." Dr. Brendan Furlong works with horses at the major international championships, and he also competes in eventing. He named breeding as an important factor in finding the right event horse. "The best horses are Irish Thoroughbred, English Thoroughbred, and New Zealand Thoroughbred crosses. If you look at the bloodlines, they all go back to solid, steeplechasing bloodlines, crossed with the basic Irish hunter for a sound, bold, brave horse. Going cross-country comes very natural to them." The World Breeding Federation for Sport Horses (WBFSH) awards studbooks for accomplishments in the three Olympic disciplines. In the first three years of the Eventing World Breeding Championship, the Irish Sport Horse placed first. This breed is a cross between the Thoroughbred and the Registered Irish Draught. In 1996-1997, the French breeds of Selle Francais and Anglo-Arab placed second and third to the Irish Sport Horse. Both also rely on Thoroughbred bloodlines. The horse's conformation enables him to jump. Furlong described as ideal the look of a steeplechaser: "He has substance to his limbs, with well-placed limbs and a rangy look. He gives you the appearance that he can gallop all day." This athlete has a sloped shoulder and croup. Alan Young, DVM, a member of the FEI Veterinary Committee, noted, "In the elite event horses, withers and shoulders are a predominant feature." Leg length and joint angles allow the horse to gallop efficiently, with a long stride with impulsion. A study of 54 horses which completed the Barcelona Olympic Three-Day

Event linked shorter cannons---fore and hind---with superior results. "You want the ideal leg," said O'Dea, "with a proper angulation of pastern, a good, deep shoulder, slightly shortened cannon, and good, big, flat knee. It's a matter of being able to handle stress in the course of the competition. You look for a mechanically correct animal." For any eventer, Furlong named the foot as crucial. "They all have to have a good conformation and good-made foot, with the size, shape, and integrity. The horse has to keep his shoes on going cross-country. If he loses a shoe there on Saturday, then on Sunday he very likely will not be able to complete the event in jumping." He added that varied climates in the United States increase the difficulty of keeping feet in good condition. "In Britain and New Zealand, the ground is soft and the site is free of flies. Horses there don't stomp all the time and break up their feet, as they can do here." Kent Allen, DVM, practices equine sports medicine at his private clinic in Virginia, and he coordinated veterinary services for the 1996 Olympic Games. At a seminar prior to the Olympics, he noted, "More horses go lame from inappropriate shoeing than any other single factor I can name. Pay attention to the horse's shoeing. You can't prevent that one bad step---what you can do is prevent repeated concussion and trauma due to a horse having inappropriate angles on his feet." Allen recommended that riders conduct a shoeing evaluation with the equine practitioner and farrier together once a year, or twice a year if the horse competes significantly. For an eventing prospect or campaigner, Allen also advised limb evaluation through flexion. "Passive flexion is where you pick up the limb and do range of motion. Active flexion is what you do in a lameness exam. Flex the joint for 30 seconds and jog the horse off." This will pick up more subtle lamenesses. A deep heart girth, broad chest, and well-sprung ribs indicate a horse with the lung capacity to maintain stamina over the miles. The back shouldn't be too long, as today's courses present the horse with tight turns before or after jumps, especially in a complex (a combination) consisting of two to four obstacles close together, often with just a bounce between the jumps. For these multiple jumping efforts, the horse of longer body length loses time by slowing in the turns or may not be able to compress his body to make the jump. "The short-coupled back is ideal---short so the saddle covers it," said Furlong. "The wellconformed back makes the horse able to carry weight, so he doesn't develop sore muscles and then compensate for his back somewhere else." A horse's attitude makes him excel in eventing. Winning horses seem born with a desire for the course. "Most horses love cross-country," said USET rider Mike Huber. "You see them get excited, getting ready to go out of the starting box. They love to run and jump. The horse won't back off. He just jumps right in stride, ears pricked. When he lands, he just gallops away---like the jump wasn't even there!"

The good event horse trusts his rider, and he will boldly attempt any fence---even if he can't see where he'll land. Cross-country courses include drop fences, where the horse can't anticipate that he has to leap straight down. Water jumps challenge him to jump in without knowing the depth. This fearless horse must still cooperate with the rider to maintain his equilibrium. Top event horses are willing to partner with their riders, showing the flexibility to adapt to the subtleties of dressage while at the peak of conditioning for speed and endurance. Eventing requires a smooth, flowing stride at the gallop. The horse finds his rhythm and maintains speed, to complete the course within time constraints. In jumping, the "catlike" horse is strong, yet supple. He's also adjustable, able to lengthen for a spread jump and then collect for a vertical, so he flows over the obstacles. If necessary, he "thinks on his feet" to carry the rider over a tricky fence. The horse should move with impulsion at all gaits, coming underneath himself in a flowing motion. His dressage scores will benefit if he has pure, regular gaits and can relax his back to come "through," or on the bit. Physical Limitations The course designer faces the challenge of posing questions suitable for rider and horse, while considering their safety. This expert balances the effects of terrain and climate with the permitted distances and obstacles. Even when matched to an ideal course, the horse can run only so long before suffering exhaustion or injury. Veterinary care and official inspections aim to maintain the animal's well-being by limiting its stress. Competition rules specify the roles of equine practitioners as veterinary officials. At international events, FEI Veterinary Regulations require veterinarians to perform examinations before and during the event to determine the horses' health status. There, they encounter seasoned horses which have conquered injuries and unsoundness. They establish a baseline of each animal's condition, as they take such "wear and tear" into account when evaluating fitness for competition. Two veterinary inspections occur during a three-day event---before dressage and before stadium jumping. The ground jury, with veterinarians participating, performs the inspections. Each rider presents his horse to the jury, standing the horse up for observation and jogging the horse in hand. The jury accepts each animal which appears sound and re-inspects those of questionable soundness. A horse is spun or disqualified if he does not jog sound or is perceived to have other health issues. As the sport has grown in the past 25 years, so has criticism from those concerned with animal welfare. Critics argue that the cross-country phase can overtax the horse's abilities, and that horses suffer when riders push them too hard over punishing courses. The sport is changing to respond to such concerns. For example, USEF and FEI rules now require a competitor to retire if the horse falls during the cross-country phase, and

the horse and rider are eliminated if the rider falls off, even if the rider lands on his or her feet. At most of the recent Olympics trials, a veterinarian was present at each jump to monitor the horses' fitness on course. Huber explained how eventing continues to improve: "There are new events, and courses are being upgraded. It's the quality of the jumps and the quality of the ground that are critical. People prepare the footing---the soil and the grass. Today, half the time you ride over a manicured type of track or a golf course that has been aerovated to allow it to be softer." The FEI announced a critical decision about ten years ago---to eliminate the requirement that horses carry a minimum weight of 75 kilograms. O'Dea discussed the origin of this change, from his contention to prove the adverse affect of the horse carrying dead weight. He provided initial funding for a research project conducted by Hilary Clayton, BVMS, PhD, formerly at the University of Saskatchewan and now at Michigan State University. O'Dea explained, "When you add weight, the horse has a bigger need to overcome gravity. To jump, he has to get closer to the fence to marshal all his forces, all his impulsion to carry that weight over the fence, in addition to his own weight and that of the rider. He lands closer on the other side and overextends. That can result in bowed tendon, ruptured check ligament, fractures in phalanges, and sometimes fractures in the carpus. If his weight is too far forward, the horse somersaults." Clayton videotaped horses in conditions that simulated speeds and distances of Phases A, B, and C. She measured placement of the horse's forelegs, especially joint angles, during landing. Her poster session, presented at the Third International Workshop on Animal Locomotion, noted: "In the added-weight condition, both forelimbs landed closer to the fence. There was greater hyperextension of the carpal and metacarpophalangeal joints in the leading forelimb, and the pastern segment of the leading forelimb rotated to a more horizontal position during the landing." Clayton said, "Suspensory ligament strain depends on the angle of the fetlock joint, so extra weight overloads the horse. He's closer to a suspensory problem." Her research also showed that the hind legs remained on the ground longer when carrying extra weight. The horses were less balanced due to changes in angles of head, neck, and body. A former eventer in England, Clayton is pleased with how her research has benefited future competitors. She said, "The main thing that's come out of it is the FEI response. It's more than I ever dreamed would happen." Across the Country As the sport's highlight, cross-country jumping includes "technical" obstacles that require the horse to adjust speed and arc. Design and placement test how the horse confronts each

jumping effort. Obstacles vary by height and width, approach (straight, sloped, or after a turn), landing (ground or water), and distance between adjacent obstacles. Certain obstacles might be designed to present options---either a faster, more difficult jump, or a slower, safer one that takes a lot more time. The route is up to the individual rider. Fences recreate those a horse would encounter while foxhunting---solid and awesome rather than the artificial fences of the show ring. Yet, rules require a construction that allows officials to dismantle such obstacles quickly if a horse becomes entrapped in or over the rails. For cross-country, the horse must be conditioned to a level of fitness appropriate for the level of competition. The animal builds muscle mass and power, so he is strong enough to clear all fences safely. A horse that "bellies" over a fence loses energy and confidence. Galloping develops the horse's condition through biomechanical and metabolic stress. The rider and coach plan to bring the horse to peak condition for the event. The program aims to balance the work between too much stress, overfitting, or insufficient preparation. When running a distance at speed, these horses perform both aerobic and anaerobic work. O'Dea explained: "The Thoroughbred has the ability to go on. When the normal aerobic metabolism reaches the end of its capacity, an enzyme shift occurs so the animal can go on in an anaerobic state." To condition the horse, many trainers practice interval training. This method overloads the horse by exercising him to the point of fatigue, then resting him. The horse builds greater capacity to perform aerobic work, which postpones buildup of lactic acid. Trainers check the horse's recovery rates for indication of metabolic fitness. The rider constantly evaluates the horse's freshness during schooling and competition. The late A. Martin Simensen, DVM, was veterinarian for the USET from 1974 to 1996. At the 1990 World Equestrian Games in Stockholm, Sweden, he described the role of the attending veterinarian in the speed and endurance test. "During the inspection after the horses' going cross-country, we monitor the health of the horses very closely. We watch the horse's temperature, his pulse rate, his respiration, and we check to see if there are any injuries. After the horse completes the course, we direct the cooling out process. It's a tension-packed time, and the time when we can exert our greatest influence over the horses." The day of the cross-country in Stockholm was surprisingly warm for that city, and Simensen noted that several horses completed the test "in total exhaustion, suffering heat stroke. It was due to the hard work of the grooms and attendants, under the direction of the veterinarians, that these horses were able to continue and jump the next day." Staying Sound Simensen described soundness as an essential characteristic. "Not only does a sound horse do the best job, but soundness is judged and is part of the competition in the threeday event. It's essential that the horses that are chosen to represent the United States are

sound so they perform well. They can be eliminated during the official inspections, thereby decimating the team." In the heat of competition, riders tend to push a tired horse to complete the course. They might press the horse beyond his physical ability. When he's fatigued and has built up lactic acid in his muscles during speed work, he's more likely to sustain injury. Officials have the right to remove horses from competition, but pulling an exhausted horse is like a referee stopping a boxing match---especially at a high-profile venue where the rider might be on the way to a medal. "I see no major problems at the international level, except lack of conditioning," said O'Dea. "The horse has to be muscle fit to the max. As he fatigues, muscles lengthen and the tendons connected to those muscles drop down, resulting in bows, suspensories, and sprained check ligaments." Equine practitioners focus on maintenance, working in partnership with riders and coaches to prevent injuries from trauma or overuse. Young mentioned the importance of fine-tuning a horse's performance. "It's muscles and backs---making every part of the body work as best it can," said Young. "Muscles are all interrelated, both the weight carrying and the motion to where the horse can carry the weight. We aim to get rid of muscle spasm, and to give every joint the best range of motion." Furlong meets with his clients monthly to examine their horses and recommend adjusting the athletes' training programs. "I give a clinical judgment, looking at the horse with flexion tests, palpation, observation of his movement, radiographs, and ultrasound. "The event horse works under conditions that the jumper or dressage rider would not contemplate. He pushes off to jump without solid footing. He can slip when he pushes, so with repeated effort, it becomes painful. It's a tremendous effort for the horse to jump at speed, and uphill." He added that, like dressage horses, the eventer develops problems in the hind end. Hock problems can range from soreness to degenerative joint disease, and horses also have sore stifles and sprained and sore gluteal muscles. Allen described evaluating a horse's legs through examination and observing the horse in motion. "Know the horse's lumps and bumps, what's new, what's old, and tendon and ligament palpation is important. Everyone should be able to palpate the horse's tendons and ligaments. You should know what they feel like---what you're looking for are changes in size and consistency. The horse can be going on fine, you're moving him up a level, all of a sudden there's a little bit more windpuff behind than there used to be." Such a slight change can predict if the horse might damage the lateral suspensory branch. Accidents on the course can be due to the terrain itself, or a horse can misjudge a fence and hit the obstacle. He usually will regain his balance and continue galloping to the next fence, but the injury can result in inflammation or strain. The worst outcome is the rotational fall, when the horse somersaults, sometimes breaking his neck or falling on the

rider. These are devastating falls, and the USET and the FEI are funding studies to try to decrease their incidence. Furlong noted that most injuries occur in the lower limbs. "Wear and tear manifests itself in the distal limb: tendinitis, mild tendon sprain, and suspensory problems. In the drop fence, you see more high suspensory problems and problems at the back of the knee, sprain of carpal ligaments, suspensory branches, and distal sesamoiditis." Horses also suffer other conditions, such as dehydration and tying-up. Furlong described three conditions related to the tying-up incidents he sees: "The first-time rider at a threeday event, a horse that's not conditioned, or the inexplicable occurrence of a horse that ties up for the first time ever. For example, that could be from a wet and muddy course--when the horse puts out extra effort to stay upright and go fast at the same time." Eventing tests how contemporary horses meet the traditional requirements of endurance, obedience, and scope. Although a high-risk sport for both human and equine athletes, the eternal challenge of horse and course thrills participants.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- 2006 Drought StrategiesDocument3 pages2006 Drought Strategiesfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Parasite Control Guidelines FinalDocument24 pagesParasite Control Guidelines Finalfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Ischeminc Myelopathy in 52 DogsDocument9 pagesIscheminc Myelopathy in 52 Dogsfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- AVMA Background Sheep Tail DockingDocument3 pagesAVMA Background Sheep Tail Dockingfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Ethical and Professional Guidelines: Position Statement Protocol (2010)Document29 pagesEthical and Professional Guidelines: Position Statement Protocol (2010)freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Bio Guidelines Cont of Ven Trans DisDocument22 pagesBio Guidelines Cont of Ven Trans Disfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Animal Welfare AVMA Policy - Animals Used in Entertainment, Shows, and For ExhibitionDocument1 pageAnimal Welfare AVMA Policy - Animals Used in Entertainment, Shows, and For Exhibitionfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A A Ep Care Guidelines RR 2012Document36 pagesA A Ep Care Guidelines RR 2012freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Bio Security Guidelines Final 030113Document5 pagesBio Security Guidelines Final 030113freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Adult Vaccination Chart Final 022412Document5 pagesAdult Vaccination Chart Final 022412freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Foal Vaccination Chart Updated 090612Document5 pagesFoal Vaccination Chart Updated 090612freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Equine Physical Exam and Restraint ReviewDocument6 pagesEquine Physical Exam and Restraint Reviewfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Herd Health Protocols For Heifers: Clostridium Type A SeleniumDocument1 pageHerd Health Protocols For Heifers: Clostridium Type A Seleniumfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Equine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM) & EHV-1: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument2 pagesEquine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM) & EHV-1: Frequently Asked Questionsfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biosecurity On Dairies: A BAMN PublicationDocument4 pagesBiosecurity On Dairies: A BAMN Publicationfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Cow Calf Vax ProtocolDocument4 pagesCow Calf Vax Protocolfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical MastitisDocument1 pageClinical Mastitisfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dry Cow Protocol: Internal Teat SealantDocument1 pageDry Cow Protocol: Internal Teat Sealantfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Herd Health Protocols For The Cowherd: MLV VaccineDocument1 pageHerd Health Protocols For The Cowherd: MLV Vaccinefreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Biosecurity On Dairy FarmsDocument2 pagesBiosecurity On Dairy Farmsfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Management Cycles in Beef Production: F. Glen HembryDocument14 pagesManagement Cycles in Beef Production: F. Glen Hembryfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hmlesson 4 Biosecurity Antibiotic Use and Beef Quality AssuranceDocument12 pagesHmlesson 4 Biosecurity Antibiotic Use and Beef Quality Assurancefreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bio SecurityDocument2 pagesBio Securityfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef Herd Health CalanderDocument4 pagesBeef Herd Health Calanderfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide To Calf Milk Replacers Types, Use and QualityDocument4 pagesA Guide To Calf Milk Replacers Types, Use and Qualityfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef Vax ProtocolDocument3 pagesBeef Vax Protocolfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef Cattle Vax ProtocolDocument2 pagesBeef Cattle Vax Protocolfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef Cattle Vax Protocol2Document4 pagesBeef Cattle Vax Protocol2freak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Biosec Ip Dairy HerdsDocument4 pagesBiosec Ip Dairy Herdsfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Beef0708 Is BiosecurityDocument4 pagesBeef0708 Is Biosecurityfreak009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Waste Management in Sri Lanka Performance and Environmental Aiudit Report 1 EDocument41 pagesElectronic Waste Management in Sri Lanka Performance and Environmental Aiudit Report 1 ESupun KahawaththaPas encore d'évaluation

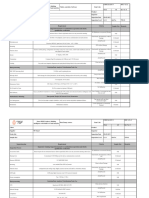

- Quality Assurance Plan-75FDocument3 pagesQuality Assurance Plan-75Fmohamad chaudhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk Management: Questions and AnswersDocument5 pagesRisk Management: Questions and AnswersCentauri Business Group Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Photoshoot Plan SheetDocument1 pagePhotoshoot Plan Sheetapi-265375120Pas encore d'évaluation

- Feature Glance - How To Differentiate HoVPN and H-VPNDocument1 pageFeature Glance - How To Differentiate HoVPN and H-VPNKroco gamePas encore d'évaluation

- Computer Science HandbookDocument50 pagesComputer Science HandbookdivineamunegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Actara (5 24 01) PDFDocument12 pagesActara (5 24 01) PDFBand Dvesto Plus CrepajaPas encore d'évaluation

- IRJ November 2021Document44 pagesIRJ November 2021sigma gaya100% (1)

- Dehydration AssessmentDocument2 pagesDehydration AssessmentzaheerbdsPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- COACHING TOOLS Mod4 TGOROWDocument6 pagesCOACHING TOOLS Mod4 TGOROWZoltan GZoltanPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 1-2 Module 1 Chapter 1 Action RseearchDocument18 pagesWeek 1-2 Module 1 Chapter 1 Action RseearchJustine Kyle BasilanPas encore d'évaluation

- Data SheetDocument14 pagesData SheetAnonymous R8ZXABkPas encore d'évaluation

- ZyLAB EDiscovery 3.11 What's New ManualDocument32 pagesZyLAB EDiscovery 3.11 What's New ManualyawahabPas encore d'évaluation

- Creativity Triggers 2017Document43 pagesCreativity Triggers 2017Seth Sulman77% (13)

- SchedulingDocument47 pagesSchedulingKonark PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Success - Stakeholders 1 PDFDocument7 pagesProject Success - Stakeholders 1 PDFMoataz SadaqahPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Tools PDFDocument57 pagesMachine Tools PDFnikhil tiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- DSS 2 (7th&8th) May2018Document2 pagesDSS 2 (7th&8th) May2018Piara SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Promoting Services and Educating CustomersDocument28 pagesPromoting Services and Educating Customershassan mehmoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Facts About The TudorsDocument3 pagesFacts About The TudorsRaluca MuresanPas encore d'évaluation

- Installation, Operation & Maintenance Manual - Original VersionDocument11 pagesInstallation, Operation & Maintenance Manual - Original VersionAli AafaaqPas encore d'évaluation

- Using MonteCarlo Simulation To Mitigate The Risk of Project Cost OverrunsDocument8 pagesUsing MonteCarlo Simulation To Mitigate The Risk of Project Cost OverrunsJancarlo Mendoza MartínezPas encore d'évaluation

- Malaybalay CityDocument28 pagesMalaybalay CityCalvin Wong, Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Innovator - S SolutionDocument21 pagesThe Innovator - S SolutionKeijjo Matti100% (1)

- Using Ms-Dos 6.22Document1 053 pagesUsing Ms-Dos 6.22lorimer78100% (3)

- N164.UCPE12B LANmark - OF - UC - 12x - Singlemode - 9 - 125 - OS2 - PE - BlackDocument2 pagesN164.UCPE12B LANmark - OF - UC - 12x - Singlemode - 9 - 125 - OS2 - PE - BlackRaniaTortuePas encore d'évaluation

- Vicente BSC2-4 WhoamiDocument3 pagesVicente BSC2-4 WhoamiVethinaVirayPas encore d'évaluation

- Design and Analysis of DC-DC Boost Converter: September 2016Document5 pagesDesign and Analysis of DC-DC Boost Converter: September 2016Anonymous Vfp0ztPas encore d'évaluation

- 3114 Entrance-Door-Sensor 10 18 18Document5 pages3114 Entrance-Door-Sensor 10 18 18Hamilton Amilcar MirandaPas encore d'évaluation

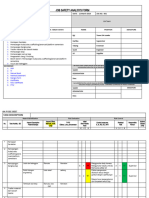

- JSA FormDocument4 pagesJSA Formfinjho839Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Faraway Horses: The Adventures and Wisdom of America's Most Renowned HorsemenD'EverandThe Faraway Horses: The Adventures and Wisdom of America's Most Renowned HorsemenÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (49)

- Traditional Blacksmithing: The Fine Art of Horseshoeing and Wagon MakingD'EverandTraditional Blacksmithing: The Fine Art of Horseshoeing and Wagon MakingPas encore d'évaluation

- Horse Care 101: How to Take Care of a Horse for BeginnersD'EverandHorse Care 101: How to Take Care of a Horse for BeginnersÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- The USPC Guide to Longeing and Ground TrainingD'EverandThe USPC Guide to Longeing and Ground TrainingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Fitness Evaluation of the HorseD'EverandFitness Evaluation of the HorseÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Stable Relation: A Memoir of One Woman's Spirited Journey Home, by Way of the BarnD'EverandStable Relation: A Memoir of One Woman's Spirited Journey Home, by Way of the BarnÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Joey: How a Blind Rescue Horse Helped Others Learn to SeeD'EverandJoey: How a Blind Rescue Horse Helped Others Learn to SeeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (23)