Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Black Ware Pottery of The Pueblo

Transféré par

On DriTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Black Ware Pottery of The Pueblo

Transféré par

On DriDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

McCullough1 Andrea McCullough Dr.

Solari Anthropology 220 21 March 2013 Black Ware Pottery of the Pueblo To the Western eye Santa Clara black ware pottery draws aesthetic appeal from its simplicity. The texture and monochromatic geometric decoration seem direct and tasteful highly appropriate for collections of decorative arts. In particular, the black ware pots of Maria Martinez and her husband Julian from San Ildelfonso were valued by collectors such as Emily Johnston De Forest. Although the work of the couple is undeniably exquisite, the pots represent a deeper system of meaning than the aesthetic pleasure the Western eye seeks. Santa Clara black ware pottery is not only a depiction of earlier Tewa cosmology, it is a representation of ritual importance and a celebration of the proud cultural heritage of the modern Pueblo people (Naranjo 47). At the same time, the pottery is a microcosm for Western contact with Native America cultures, showing the aftermath of Western influence on indigenous peoples. Even from a single piece, such as the pot held in the Matson from the De Forest collection by Maria Martinez, these greater themes can be discerned when examined in the context of the larger body of work and ethnographic records. Santa Clara black ware pottery is a style of ceramic production which flourished in the late 19th century and early 20th. It is known for its lustrous black finish that later became decorated either with geometric carving, slip-drawn, or incised design (Pueblo Indian Pottery 12), although the designs themselves are strictly regimented, limited only to geometric and natural designs (Pottery of San Ildelfonso 13). Maria Martinez is particularly renowned for her

McCullough2 work in the Santa Clara style. In fact, she is considered one of the most famous and important Native American artists of the 20th century (Nunley 11). Born in the San Ildelfonso pueblo, a close neighbor of Santa Clara and a town descended from the same Tewa culture, Maria was an active potter from the turn of the 20th century through the 50s. She and her husband Julian refined to technical perfection the Santa Clara method of firing red clay slip to a polished black sheen (Nunley 11). In regards to cultural significance, the Santa Clara black ware is an expression of Pueblo heritage. The making of pottery was a very spiritual act symbolizing communion with nature in the Pueblo Tewa culture (Pueblo Indian Pottery 14). According to the cosmology, the lower half of the universe is a pot which contains life. Containment itself is an inherently sacred concept in Tewa mythology, as the earth, as well as buildings contain human life, making everything people do possible (Naranjo 47). Thus pottery becomes a sacred symbol which is not only domestically and ritually functional but cosmologically representative. The creation of pottery was also seen as a communal and interactive experience. Pueblo potter Tessie Naranjo remembers gathering clay with her family as a child, praying and singing to the clay as it was prepared (Naranjo 48). As opposed to Western art, pottery was not the product of a single artist. In addition to representing Pueblo cultural values, black ware pottery is also directly derived from Western influence on these same values. The reawakening of Pueblo ceramic tradition in the late 19th and early 20th centuries occured in response to Western interest in the Pueblo, sparking a demand for Pueblo goods (Naranjo 47). Tourists and anthropologists alike visited the Pueblo, looking for reproductions of prehistoric works (Pueblo Indian Pottery 11). Durable and beautiful, ceramic goods were a natural market for souvenirs. Indigenous artists like Maria Martinez began to refine the classic style of Santa Clara pottery to please Western visitors.

McCullough3 Although today, she is not even given credit for the innovations in black ware pottery. In fact, in the book, The Pottery of San Ilfefonso Pueblo, contributor John G. Meem cites Western author Kenneth Chapman as catalyzing the style, saying it was Chapman who influenced Julianand his wife Mariato use native designs and the traditional black polished ware technique in making their pottery, thereby sparking a revival of excellence in the making of Indian pottery. (Pottery of San Ildefonso v). On top of Pueblo efforts to please patrons, Western collectors began to encourage artists to sign their work, increasing the value of the pot and stimulating competition. For example, Western collectors pressured Maria Martinez to start sign her pots after 1920 (Nunley 11). Traditional Pueblo beliefs do not advocate signing artworks. People were able to tell pots about by the unique style and small idiosyncrasies of each potter (Nunley 11), not a specific declaration of ownership. Beyond changes in technical aspects and competition, Western influence removed the greater cultural significance of pottery making. In contrast to Naranjos earlier experience, Betty LeFree recorded that there was no ritual associated with clay gathering by the time she conducted her ethnographic research in 1968 (Naranjo 47 and LeFree 9). This represents the loss of cosmological significance as the clay was considered to be mother earth herself, the holder of life (Naranjo 47). Disrespect of the clay would be an insult to life itself. In the end, even a singular piece of Santa Clara reflects these cultural attributes. The smooth, polished, black surface marks it as a piece of Santa Clara style black ware from the turn of the century, a time of great change in the spectrum of Pueblo pottery. The pottery itself symbolizes a revival of the Tewa Pueblo heritage which stresses the dual importance of ritual and cosmology. Next, an analysis of the technical aspects, for example, few bumps, proper

McCullough4 thickness, signify that the piece is the work of Maria Martinez. The signature clearly defines the pot as one of her pieces after 1920, produced under extreme Western pressure to change traditional procedures. Appreciation of Santa Clara black ware pottery is not only limited to its aesthetic appeal. In reality, from a single piece to the entire body of work, the style represents the duality of life as a modern Pueblo, or even a modern Native American. On one hand there is tradition and heritage. The other, Western values such as economic demand, aesthetic pleasure, and individualism. Santa Clara black ware pottery is the reconciliation of these two themes, creating a microcosm of the cultural experience of the Pueblo people in the modern era. Word Count: 1036

McCullough5 Works Cited Chapman, Kenneth M. The Pottery of San Ildefonso Pueblo. 2nd ed. Vol. 28. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1970. Print. Monograph Ser. Chapman, Kenneth M. Pueblo Indian Pottery of the Post-Spanish Period. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Laborartory of Anthropology, 1945. Print. General Ser. LeFree, Betty. Santa Clara Pottery Today. Vol. 29. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1975. Print. Monograph Ser. Nunley, John W., and Janet Berlo. "Native North American Art." Bulletin (St. Louis Art Museum) 20.1 (1991): 1-47. JSTOR. Web. 14 Mar. 2013. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40716244>. Naranjo, Tessie. "Pottery Making in a Changing World." Expedition (University Bulletin, University of Pennsylvania) 36.1 (1994): 44-51. Periodicals Archive Online. 2006. Web.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Casi Casi - InglêsDocument2 pagesCasi Casi - InglêsjuniorenniePas encore d'évaluation

- English Camp 2012 ETA ReportDocument26 pagesEnglish Camp 2012 ETA Reportsal811110Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Dying Gaul BrochureDocument4 pagesThe Dying Gaul BrochureAnita MantraPas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Booklet La La LandDocument6 pagesDigital Booklet La La Landchivas10270% (1)

- Ellen Original PantsDocument10 pagesEllen Original Pantsblueskyder100% (1)

- KC Shito-Ryu Dan Test Guideline Eng 20120221Document4 pagesKC Shito-Ryu Dan Test Guideline Eng 20120221Miguel Nacarino BejaranoPas encore d'évaluation

- 6770Document138 pages6770Edward Xuletax Torres BPas encore d'évaluation

- Ragged Mountain CampDocument2 pagesRagged Mountain Campjim_jordan_2Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Paradoxes of Digital Photography - Lev ManovichDocument4 pagesThe Paradoxes of Digital Photography - Lev ManovichsalmaarfaPas encore d'évaluation

- LESSING LaocoonDocument360 pagesLESSING Laocoonraulhgar100% (1)

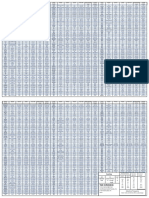

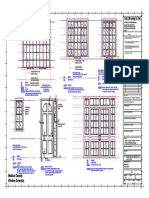

- V404-COASTAR ESTATES VILLA - A (Final)Document41 pagesV404-COASTAR ESTATES VILLA - A (Final)hat1630Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tile Scope Letter Chuck E CheeseDocument2 pagesTile Scope Letter Chuck E CheeseAbubakar MuhammadPas encore d'évaluation

- Classical Saxophone Syllabus 2019Document56 pagesClassical Saxophone Syllabus 2019Luis Felipe Tuz MayPas encore d'évaluation

- Still I Rise by Maya AngelouDocument12 pagesStill I Rise by Maya AngelouRanjell Allain Bayona TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Mark Ellingham - World Music The Rough Guide Vol 1 (1999)Document790 pagesMark Ellingham - World Music The Rough Guide Vol 1 (1999)Ani TsikarishviliPas encore d'évaluation

- Crochetbrooch 1Document11 pagesCrochetbrooch 1Catarina Bandeira100% (8)

- 09 Ela30 1 Eosw Jan2016 - 20161222Document103 pages09 Ela30 1 Eosw Jan2016 - 20161222Nabeel AmjadPas encore d'évaluation

- DfgyguygtfrrDocument45 pagesDfgyguygtfrrRavi MehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- Wolfgang Rihm - Biography - Universal EditionDocument4 pagesWolfgang Rihm - Biography - Universal EditionEtnoPas encore d'évaluation

- PZO9504 U1 - Gallery of Evil PDFDocument36 pagesPZO9504 U1 - Gallery of Evil PDFJhaxius100% (9)

- Verb TableDocument2 pagesVerb TableVladimir CoronaPas encore d'évaluation

- Window and Door ScheduleDocument1 pageWindow and Door ScheduleCharles WainainaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fire Power!: Follow Our Naked Raku AdventureDocument84 pagesFire Power!: Follow Our Naked Raku AdventureJesusa100% (4)

- How To Read Sheet Music WorkbookDocument40 pagesHow To Read Sheet Music WorkbookJohn Peter MPas encore d'évaluation

- Lev Manovich On Totalitarian Inter ActivityDocument3 pagesLev Manovich On Totalitarian Inter ActivityHerminio BussacoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jean-Michel Gardair - An Interview With Pier Paolo PasoliniDocument2 pagesJean-Michel Gardair - An Interview With Pier Paolo PasolinialeksagPas encore d'évaluation

- Paula Scher - Works Available - Commissioned by ARTContent Editions LimitedDocument6 pagesPaula Scher - Works Available - Commissioned by ARTContent Editions LimitedARTContentPas encore d'évaluation

- BÉHAGUE, Gerard - Improvisation in Latin American Musics - Music Educators Journal, Vol. 66, No. 5 (Jan., 1980), Pp. 118-125Document9 pagesBÉHAGUE, Gerard - Improvisation in Latin American Musics - Music Educators Journal, Vol. 66, No. 5 (Jan., 1980), Pp. 118-125Maurício Mendonça100% (1)

- Zimbabwe Culture StatesDocument58 pagesZimbabwe Culture StatesTafadzwa V ZirevaPas encore d'évaluation

- EScholarship UC Item 9jg5z235Document341 pagesEScholarship UC Item 9jg5z235LászlóReszegiPas encore d'évaluation