Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Migrant Workers

Transféré par

VishyataCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Migrant Workers

Transféré par

VishyataDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MIGRANT WORKERS IN MALAYSIA: PEOPLE AND POLICIES

Shankaran Nambiar Senior Research Fellow Malaysian Institute of Economic Research Email: sknambiar@yahoo.com

MIGRANT WORKERS IN THE MALAYSIAN LABOUR MARKET: PARTICIPATION AMIDST POLICY INCONSISTENCY

ABSTRACT Migrant labour has had a long history of participation in Malaysias economic development. Indeed, migrant labour continues to play an important role in the countrys labour market. Since the late1980s the country has had vigorous growth rates and this has necessitated an adequate supply of labour, an issue that has been of particular concern especially since the early 1990s. In the 1980s the government encouraged the growth of the manufacturing sector, with the consequent effect of necessitating more labour for the agriculture sector because of the consequent rural-urban flow and the shortage of labour in the agriculture. Increasingly there has been demand for labour in the manufacturing, construction and services sectors for jobs that are not favoured by domestic workers. Despite Malaysias reliance on migrant labour, its policies have not been consistent, alternating between a stance that is favourable to migrant workers and one that seeks to ban their presence. Nonetheless, there is evidence that the economy would suffer in the absence of migrant labour. The wages in the manufacturing and construction sectors are dampened due to the presence of migrant workers. Further, the availability of cheap migrant workers has been beneficial to subsectors within the services sector, primarily in the hotel industry and as maids. The latter permits Malaysian women to play a more active role in the labour market. However, insufficient attention has been paid to the rights of migrant workers although non-governmental organisations have drawn attention to this problem.

INTRODUCTION

Migrant workers have come to occupy an increasing role in Malaysias development process. There is heated debate on the issue of migrant labour given the various aspects to the issue. On the one hand the presence of migrant labour frees some segments of the labour force to take a more active part in the labour market, the female population being particular beneficiaries. On the other hand there is concern that the easy access to migrant labour delays the process of technological upgrading in the economy.

There is little doubt that migrant labour has had an important role to play in Malaysias development path. Under the British colonial period, the country relied heavily on migrant labour for the development of plantation, mining industries as well as the building of roads and railways, later absorbing these workers to become permanent residents and subsequently as its citizens (Navamukundan, 2002). The concern now is that there is undue reliance on migrant workers and insufficient resources being directed towards attracting domestic workers towards key sectors in the economy (Narayanan and Lai, 2005). Indeed, it is also argued that migrant labour carries with it economic costs due to the health risks, threat to security and the social problems that they are perceived to cause (Tey, 1997).

This paper attempts to forward the claim that migrant workers do make a useful contribution to the Malaysian economy by helping to ease the upward pressure on wages. However, it is argued that government policy regarding migrant labour has been inconsistent and treats them as a buffer category. The paper proceeds as 3

follows. The next section provides an overview of the labour market, discussing employment trends in the key economic sectors, and thus setting the context for the role of migrant labour. This is followed by an attempt at tracing the broad policy thrusts on migrant labour in recent years. The fourth section investigates trends in the inflow of migrant workers before assessing the economic impact of migrant labour. The fifth section draws attention to ethical issues before some concluding remarks are made. THE LABOUR MARKET: A BACKGROUND

The labour force in Malaysia has been growing steadily since the 1970s. In 1970 the labour force amounted to about 3.6 million persons and now stands at about 11.2 million. Noticeable increments took place in the mid-70s when there were about 4.2 million people (1975) in the labour force, increasing to about 5.4 million in 1984. The rise continued to 6.8 million in 1989 (see Table 1). More recently, this figure reached 9.0 million in 1997 and rose even further in 2005 (11.3 million).

Alongside the increase in labour force, the unemployment rates have been rather stable, at least since the early 1990s. In 1993 the unemployment rate was 3 per cent and declined to 2.4 per cent in 1997. This, in part, explains the shortage of labour and the need for migrant labour. The effect of the 1997 Asian financial crisis showed its effects in 1998 with a rise in the unemployment rate (3.2 per cent). The unemployment rate has been hovering around 3.5 per cent in recent years, or more specifically has been at about this rate from 2002 to the present. A low unemployment rate is not something that Malaysia has always experienced. The unemployment level was about six per cent in 1984 and averaged about 8.2 per cent between 1986 and 1988. In contrast, in the years just before the crisis the unemployment rates were much lower than they are now, touching about three per cent between 1993 and 1995, reaching the lowest attained in decades in 1997.

A clearer picture of the significant role that is played by migrant workers can be obtained if we first note the contributions of the different sectors to GDP and

observe the demand for labour exhibited by the respective sectors. Agriculture, which contributed up to 33 per cent of GDP in 1970, has been making smaller contributions in successive years (Table 2). The contribution of agriculture to GDP has been no more than eight per cent in 2005, a consequence of Malaysias development strategy. Manufacturing, on the other hand, has increased from 12.8 per cent of GDPs share to about 32 per cent. Construction has more or less maintained an even keel, as has the services sector.

In term of employment, the agriculture sector was the largest source of employment, accounting for more than 50 per cent of total employment in 1970 (Table 3). By 2000, only about 15 per cent of the labour force was engaged in agriculture. The decrease in the size of the labour force that is devoted to the agriculture sector denotes the increasing opportunities that came about with the rise in industrialisation, a phenomenon that arose with the explicit government drive to promote the manufacturing sector and which came to a head under the Second Industrial Master Plan (Ministry of International Trade and Industry, 1996). The manufacturing sector has come to play a more important role in generating employment as evidenced by the employment generated by this sector. Close to nine per cent of total employment was due to this sector in 1970 and this share rose to almost 30 per cent by 2005. It must be noted that the services sector has been a rising source of employment.

The growth rate of employment in the agricultural sector has been declining over the years. There was a rapid decline in the rate of employment in 1980 (-7.1 per cent), which tapered off in the succeeding years (Table 4). The decline was gentle in 1982 (-0.3 per cent) and 1983 (-0.2 per cent), only to witness a more marked downward movement in the 1990s. On the average, the rate of decrease in employment generated by the agriculture sector from 1990 to 2000 was about 2.8 per cent. Since 2000 to 2004 there has been a winding down of employment in this sector, with the employment growth touching about - 0.2 per cent. The

evidence clearly indicates that the agriculture sector is not a creator of employment. These figures highlight the fact that this sector is not a vibrant one and explains why the sector needs to depend upon migrant labour, as we shall see subsequently.

The mining sector has also displayed poor growth rates in employment. The whole decade of the 80s has been one where employment has been decreasing in this sector. There was a significant decrease in the growth of employment in mining in 1980 (- 11.1 per cent), and even more striking declines in 1985 (-34.3 per cent) and 1986 (-15.9 per cent). This negative trend continued till the end of the decade, showing a drop of about 11 per cent in 1989 and about 12 per cent in 1990. In more recent years, particularly from 2002 to 2004, this sector has generated a small positive growth in employment, recording an annual increase of about one per cent.

The manufacturing sector is one of the more consistently active sectors in the economy and it has, in the last two decades, been driving the countrys economic growth. The figures clearly attest to this fact. The development of this sector has come to need an increasing supply of labour, some of it being supplied by migrant workers. A glance at the statistics distinctly shows that between 1980 and 1986, the rate of growth in employment from the manufacturing sector has been less than five per cent. In fact in 1980, manufacturing did not spur any growth in employment; the rate of growth in employment was around one per cent in 1982 (1.5 per cent) as it was so in 1985 (1.3 per cent) and lower in 1986 (0.6 per cent).

The initiatives that were launched by the government in the mid-80s to accelerate the impetus for higher industrialisation, particularly export-oriented

manufacturing, showed their effect in the labour market in 1987 when the rate of growth in employment rose in this sector to 10 per cent; it was consistently high till 1996. Considering the period from 1988 to 1996, the growth in employment averaged 9.7 per cent. Subsequent to the crisis there have been fluctuations in the rate of increase in employment in the manufacturing sector, especially in 1998 and

2001. On both occasions this has been due to external shocks.

The construction sector has been consistently generating employment at a more encouraging rate, and it has been doing so in the last 20 years. It is only in the years soon after the 1997 crisis that the construction sector took a dip. We note that the 1998 and 1999 there was a negative growth in employment generated in this sector (-7.6 per cent and -7.5 per cent, in respective years). The most active years during which there was steady increase in the rate of growth of employment in the construction sector was from 1990 (12.5 per cent) to 1995 (19.9 per cent), averaging an annual growth rate in employment of roughly 11 per cent for the length of this period.

The rate of change in employment in the services sector has been within fairly narrow bounds since 1981. Except for 1985 when there was a huge demand for labour in this sector, the rate of growth in demand for labour has been roughly about four per cent over the period spanning 1980 to 2006. The services sector that has not been beset with undue fluctuations in the rate of growth of employment, save for rare rises and equally rare plunges (but even then never touching or crossing the zero mark).

The changing patterns in employment provide an inkling of the demand for migrant labour that has come to emerge over the years. The agriculture sector, which has been requiring a reduced demand for labour, has become less attractive as a source of employment for domestic labour. However, there are sub-sectors within agriculture which continue to demand labour that is met with the supply of migrant workers. As we shall see in a later section these are specific sub-sectors within the services sector which require migrant labour. Migrant workers who have little education and are not skilled do have a demand in some segments of the services sector.

GOVERNMENT POLICIES ON MIGRANT LABOUR

Before we proceed to examine the effect of Malaysias foreign workers on the labour market, we should examine policies that have been used by the government in managing migrant labour. By looking at these policies, a picture will emerge on the position of the government with regard to foreign workers (see Kanapathy, 2004:404-410 and Tey, 1997 for timelines on government policies). The rationale for this analysis is to determine if government policy corresponds to the movement of migrant labour and whether government policy has been wellplanned and consistent.

The Malaysian government has actively made interventions in migrant labour policies since the 1960s. The first instruments of policy are the Immigration Act 1957, followed by the Employment (Restriction) Act 1968. Both Acts, put

together, define the conditions under which foreign labour can enter and obtain employment in the country. At the time of drafting, these Acts would not have been able to anticipate the changing labour needs of the economy, and so were supplanted by other measures in accordance with the changing exigencies, as and when they occurred. Since Malaysia was basically a natural commodity-exporting country right up to the 1960s, with little industrialisation at that time, there was not much need to devise policy measures to encourage the inflow of migrant labour, neither was there a pressing concern about restricting illegal workers.

It is in the 1980s when the manufacturing sector began to take-off and process of urbanisation had deepened that labour shortages were more visible in the agricultural sector. In 1984, agreements were signed with the governments of Indonesia, Thailand and Bangladesh on the legal entry and employment of foreign workers. In particular, the Medan Agreement with Indonesia was signed to

remedy the shortage of labour in the plantation sector. Five years later, in 1989, it was realised that only 30 per cent of the foreign workers in Malaysia were registered, following which there was a freeze on the intake of Indonesian workers. Further, it was decided by the government that plantation workers on a three-year contract were to receive the same wages and benefits as were given to

locals, reducing the cost advantage that firms would have enjoyed by employing migrant labour; this was part of the attempt to restrict the intake of foreign workers.

A comprehensive policy was designed with regard to the recruitment of foreign workers in 1991. The purpose of this policy was two-fold: it was meant to safeguard the interests of foreign workers and to expedite the employment of migrant labour in areas where the labour shortage was felt most urgently. Under this policy, work permits were issued automatically to workers employed in the plantation and construction sectors, and employers seeking to employ workers in the manufacturing and services had to show evidence of difficulty in obtaining local labour. Under this initiative employers were required to make a mandatory contribution to the Social Security Organisation (SOCSO), bear the cost of recruitment and repatriation, and be accountable for foreign workers. While

facilitating the recruitment of foreign labour into specified sectors, an effort was made to make employers more accountable in the employment of foreign workers.

Aside from the policy review on the recruitment of foreign labour in 1991 another review was carried out in 2002. It should be noted that this review occurred when the economy was recovering after the downturn in 2000. One of the policy decisions that was taken was to offer a work permit for a period of three years, after which extensions of one year could be offered on two successive occasions. In the case of skilled workers extensions beyond the five-year period were permitted, subject to the workers being from industries which experienced severe skill shortages. It was also decided that the predominance of any one nationality among foreign workers would be discouraged. It was decided that the intake of Indonesian workers would be halved and permitted employment only in the plantation sector and as household maids. To counterbalance the prevalence of Indonesian foreign workers, the government approved the intake of workers from Uzbekhistan, Kazakshstan and Turkmenistan. In order to streamline the

recruitment of foreign workers recruitment was to be done on a government-togovernment basis.

Several attempts have been made to regularise foreign workers, notable among them was an attempt was made in 1992 to regularise foreign workers. The foreign worker regularisation programme was launched in 1992, for a period stretching from January 1992 to August 1994, to legalise illegal workers, leading to the registration of almost 500,000 illegal workers. The bid to legalise foreign workers who had entered the country through irregular means at this point, at a time when the labour shortage was acute, is another piece of evidence that is indicative of the use of foreign labour as a buffer category. This exercise to legalise illegal foreign workers was followed by a similar attempt in 1996. Foreign worker regularisation programmes specifically targeted at Sabah and Sarawak were executed in 1997 and 1998, respectively. The government has had recurring concerns about illegal workers and in this vein an amnesty was granted in 2002 to foreign workers. Those with no documentation were given the option of leaving the country voluntarily, free of any punitive action being taken against them. This was well received and resulted in about 570,000 undocumented workers leaving the country.

The government policy on migrant workers has, perhaps, been poorly conceived and even more poorly executed. The first issue that is of concern is the recurrent problem of illegal workers. In spite of the repeated attempts to weed out illegal workers this continues to be a problem. There are many reasons why the problem may be difficult to root out, and this includes the geographical proximity of countries that supply such workers. But beyond that the problem also persists because of inadequate border controls, something that reduces itself to the question of stricter implementation mechanisms.

Equally troubling is the ad hoc manner in which workers are invited into the country; but with bans being imposed on workers with regularity. For instance, in April 1993 there was a ban on the further recruitment of all unskilled foreign workers. This was lifted in June, 1993 for those workers with selected skills following appeals by employers. Again, in January, 1994 a ban was re-imposed

10

that applied to all sectors and this ban was lifted after six months for the manufacturing sector. Understandably, in August 1997 there was a ban on the recruitment of all workers due to the financial crisis. The restriction disallowing the recruitment of domestic maids was relaxed a month later, whereas the ban for other workers ceased to be effective in November 1998.

In the aftermath of the crisis, it was thought, and rightly so, that Malaysias dependence on foreign workers had to be reduced. This was justifiable since it addressed the unemployment arising from the debacle as well as the outflow of currency. Subsequent to the August 1997 ban on the recruitment of all foreign workers was the ban on the renewal of work permits for foreign workers in the manufacturing, construction and service sectors. The only sector that was exempt from this ban was the plantation sector. As if to bolster the strength of the ban on new recruitment, the government raised the annual levy to be paid by foreign workers and required employers to make mandatory contributions to the national pension fund. Both of these policy directives were introduced with the intention of creating disincentives to the employment of foreign workers. It should be noted the increase in annual levy was not marginal because the levy for workers in the construction and manufacturing sectors was raised from RM1,200 to RM1,500 (a 25 per cent increase) and that for the service sector was raised from RM720 to RM1,500, indicating more than a 100 per cent increase. The requirement of mandatory contributions by employers to the employers provident fund (EPF) was imposed in January, 1998, but was withdrawn shortly thereafter. The initial directive required employers of all migrant workers (except domestic maids) to make payments of 12 per cent to the EPF, supplemented by employee contributions of 11 per cent of monthly wages. This requirement was revoked in 2001, indicating a reversal in policy that peppers the frequent switches in labour management strategies in the country.

There are frequent changes in policy strategies with regard to migrant labour. This vacillation in policy stance has the unfortunate effect of reducing policy credibility, making the task of implementation more difficult. Frequent changes

11

in policy position also make it difficult for firms to plan their human resource needs and, in fact, encourages them to anticipate the reversal of measures that are imposed (The Star, 2007). The 1997 ban on the renewal of work permits for migrant workers in the services sector was lifted in 1998. Similarly, the ban on the new recruitment of foreign labour imposed in 1997 was revoked in 1998. Also the annual levy that was raised in 1998 was reduced to RM1,200 in 1999. Another instance of a policy switch can be found in the 2001 ban on the intake of foreign workers from Bangladesh that was subsequently relaxed.

One issue that is striking with regard to the policy process on migrant labour is the lack of a review that is based on the well-being of foreign workers. The closest effort that was made towards taking into account the welfare function of foreign workers has been through the 1991 policy on the recruitment of foreign workers. The requirement that mandatory contribution be made to SOCSO and the option to contribute to the EPF could help improve the welfare of foreign workers. Nevertheless, the contribution to EPF is optional and is of little practical value. On the other hand, requiring the employer to bear the security bond that is place with the Immigration Department is counter-productive because this cost is passed on to the workers. The same is the case with the requirement that employers bear the costs of recruitment and repatriation, since this, too, is passed on to the employee. There are two possible reasons why these policy measures were put in place: a) they reduce the financial burden for foreign workers who have gained employment in Malaysia, and b) by virtue of the costs being borne by the employers, the welfare of migrant workers is improved. In practise, with the costs being shouldered by the workers, because employers deduct the extra costs from the salaries of the migrant workers, the foreign workers welfare functions are reduced.

There are obvious deficiencies with respect to government policies on migrant workers. In the first place, these policies, as we have seen, are poorly designed, adversely affecting the workers even when they are meant to assist them. Second, the government authorities announce bans on certain sections of migrant workers

12

from time to time, making long term planning difficult for employers. Third, some policies which appear to have the effect of improving the welfare of migrant workers, are, in fact, optional, and so have almost no real value to them. These instances tend to suggest that the policies on migrant workers are not designed with a view to attending to the welfare of these workers and work towards alleviating the short-term needs of those sectors that need a supply of labour cannot be satisfied by domestic workers.

TRENDS IN THE INFLOW OF MIGRANT WORKERS

The sustained rates of growth in the mid-1970s necessitated the inflow of migrant labour, which was drawn to support the agricultural sector. Malaysia, in this phase, was undergoing rapid industrialisation, as a consequence of which there was a net inflow of labour into the industrial areas of the country. The movement of domestic labour to urban areas created a situation of excess demand for labour in the agriculture sector. This was met with the supply of migrant labour, with the majority of workers who came into the country during this period being from Indonesia. They were brought into the country on an informal basis and employed in the agricultural sector to fill the gap that arose due to the domestic movement of labour.

Indonesia was a logical choice for foreign labour at that time because of geographical proximity, besides sharing a similar religious and cultural background. These factors have, perhaps, laid the setting for continued authorised and unauthorised labour inflows. The bulk of foreign workers may have been Indonesian, but there were also workers from Thailand and the Philippines. The influx, and accommodation, of illegal migrant workers has its origins during this period. It was estimated that there were almost one million foreign workers in the country during this period, most of whom were in the plantation and construction sectors. Official sources, on the other hand, note that a small proportion of these workers held valid documents. For instance in 1985 only about 3,500 foreigners

13

were registered as workers in the country.

There was a decline in commodity prices (principally palm oil and rubber) in 1985, leading to a recession. The recovery was swift, and in 1988 growth rates were high, reaching almost 8 per cent. By the early 1990s there was, again, a situation of labour shortage. This led to an excess demand for skilled and

unskilled labour, pushing wages of local labour up. In 1994 there were about 640,000 registered migrant workers; this number rose to about 745,000 in 1996 (see Table 6). The number of legal migrant workers sky-rocketed to about 1.5 million in 1997, only to drop to 1.2 million the following year. Once the full impact of the East Asian financial and economic crisis was felt, the need for migrant workers declined, sliding to about 900,000 workers in 1999, and settling at about 630,000 migrant workers by the year 2000. The number of illegal migrant workers in 1997 was put at one million by the Ministry of Home Affairs implying that the economy was home to as many as 2.5 million workers in that year alone, constituting close to one-third of the total labour force requirements of the country. Once again, the bulk of the foreign workers were employed in the plantation and construction sectors.

Following the 1997 crisis the economy faced a slowdown and that helped to moderate the demand for unskilled migrant workers. The GDP sank to -6.7 per cent as a result of the recession and the unemployment rose to 3.9 per cent. While an economy that has unemployment rate that is within the boundary of four per cent is often considered to be in full employment, in the Malaysian context, given the previously high levels of growth that had been achieved and the excess demand for labour that had come to be expected, an unemployment rate of 3.9 per cent was perceived as being high. The total number of retrenchments that workers had to face because of the crisis was unprecedented. A total of 83,865 workers were retrenched in 1998, most of whom (88 per cent) were local workers. This led to adjustments in government policies on migrant labour and a stricter enforcement of laws to curb the illegal entry of migrant workers, particularly from Indonesia. There was a turn-around in policies and efforts to restrict the inflow of

14

foreign workers were instituted.

In 1999 there were around 900,000 registered migrant workers. The slowdown in the electronics and electrical industry coupled with the September 11 incident caused a recession in 2001. Although official figures are not available for the number of registered migrant workers in 2002, it is interesting to note that an amended Immigration Act was enforced in August 2002. In the months before the enforcement of the Act (March July 2002), an amnesty was granted to those migrant workers who had entered illegally or had overstayed. An estimated one million workers were covered by this provision which involved repatriation without prosecution. By 2003 the economy had recovered and there was, once again, renewed demand for unskilled labour. Thus, the number of registered migrant workers was 799,685 in 2000, and in 2004 the figure rose to almost 1.4 million, gliding up, again, in 2005 to 1.9 million registered migrant workers. It is estimated that there are presently around 0.7 million illegal workers in Malaysia, close to 70 per cent of whom are of Indonesian origin.

The number of foreign workers has been increasing tremendously over the years, and in spite of the bans on them the number has been steadily rising. In the early 1980s there were about 136,000 foreign workers, but this number swung up to almost 1 million in 2000. The proportion of foreign labour was estimated to be about 10 per cent of the total labour force in 2004. As at July 2004 it was reported that there were about 1.5 million migrant workers. In the following year (at the end of May, 2005) official sources report an increase to 1.6 million that, again, rose in 2006 (1.8 million) and inched up yet again by the end of May, 2007 to1.9 million.

Several remarks, at the risk of digressing, are in order with respect to the number of migrant workers. These numbers point to an increasing contribution of migrant labour as a percentage of the total labour force. Foreign labour contributed about 10 per cent of the total labour force in 2004 and by 2007 it constitutes close to 17 per cent of the labour force. Another comment that must necessarily be made is

15

that these estimates are from official sources. The figures that have just been quoted are compiled by the Immigration Department and refer only to those workers who have entered the country legally.

There have been widespread criticisms regarding the understatement of official figures. It has been claimed that there were around two million workers prior to the 1997 crisis, 800,000 of whom were probably illegal. This statement must be juxtaposed against the official estimate of 1.2 million foreign workers being in the country at that time. It is unfortunate that statistics relating to foreign workers is not regularly published, neither is the breakdown of foreign workers by occupation or sub-sector of employment available. This tends to throw doubt on the credibility of statistics pertaining to migrant labour.

Most of the migrant workers are employed in the agriculture sector, specifically in the plantations. By July 2004 there were 335,200 foreign workers in agriculture as compared to 115,800 in 1990. These figures tend to be deceptive in the sense that although the absolute numbers have more than number, the share of foreign workers in the total employment in the sector has been declining. In 1990 foreign workers constituted almost 48 per cent of the total labour in this sector, but dwindled down to roughly 17 per cent in 2003, and accounted for 24.7 per cent in July 2004.

The sector that now most employs migrant labour is the manufacturing sector, where 30.5 per cent of the workers are foreigners. The share of foreign workers was about 10 per cent in 1990 and more than doubled in 1995 (24.1 per cent), moving up to its present value by 2001 (31.5 per cent). The construction sector, too, has come to employ a higher percentage of foreign workers, shifting from about 10.4 per cent in 1990 to 23.6 per cent in 2003. The mining and services sector show are different trend in the composition of migrant workers. The share of migrant workers is declining in the services sector, slipping from 31.3 per cent in 1990 to 25.0 per cent in 2004. On the other hand, mining has little need to foreign workers who account for less than one per cent of the labour force. This is

16

hardly surprising since mining, with the closure of tin mining, is not a substantial economic activity in the country.

The bulk of the migrant workers in Malaysia come from Indonesia. Indonesian workers have long been the majority of foreign workers in the country, with workers from Bangladesh taking second place. Between them, Indonesian and Bangladeshi workers constituted 90.4 per cent of migrant workers in 1998. More recently, the workers from these two countries account for 74.5 per cent of the total foreign labour force. The share of Bangladeshi workers has been steadily falling from 37.1 per cent in 1998 to 8.0 per cent in 2004, while that of Indonesian workers has been increasing.

Two factors are at play here. First, the government has been guided by the belief that it is unwise to entertain workers from only one source. The government has chosen to have foreign workers from diverse countries, although the rationale for choosing to permit the inflow of workers from one country rather than another (and that too for specific jobs) has never been explicitly explained. Second, the government has reduced the number of Bangladeshi workers in the country to avoid social problems that have been caused by this segment of workers. In any case, and as part of the strategy to have migrant workers from a variety of countries, labour from Nepal and Myanmar has been permitted to enter Malaysia. While Nepali labour contributed to only 0.1 per cent of the total foreign labour in 1998, by 2004 they accounted for 9.2 per cent. Similarly, migrant labour from Myanmar constituted 1.3 per cent to total foreign workers in 1998, gradually rising to 4.2 per in 2004.

The profile of foreign workers corresponds to the changing pattern of Malaysias economic development. In the early 1970s the booming agriculture sector

necessitated the inflow of migrant labour, and came to take up almost half the labour force employed in that sector. With the winding down of agriculture and the rising importance of manufacturing, the phenomenon of domestic rural-urban migration took place and the sum total of these factors pressed for more foreign

17

workers in the unskilled sections of the sector, that, anyway, was labour-intensive. Indonesian workers with no formal education quite easily filled this gap since domestic labour was more attracted to working in the urban-based manufacturing sector. These factors triggered the inflow of foreign labour from Indonesia.

Generally, there has been a situation of policy neglect over the presence of illegal migrant workers and, aside from occasional official outbursts, the inflow of migrant labour has not been effectively stemmed, something that encourages the continued presence of undocumented labour in this sector.

Nonetheless, the number of documented foreign workers has increased considerably since the 1970s. A structurally similar set of circumstances explains the inflow of foreign labour into the manufacturing sector. The excess demand for low-cost, unskilled and labour-intensive operations in manufacturing acts as a pull factor for foreign labour as it does for the construction sector. The construction sector requires labour that can undertake considerable risk, particularly in the construction of high-rise buildings. Construction activities can be carried out beyond regular working hours and at times round-the-clock and domestic labour is noted to be reluctant to participate in such work at the prevailing wage rates.

The services sector is growing rapidly and is set to be the engine for economic growth as Malaysia moves towards developed country status. Accordingly, the demand for labour in this sector will increase. Nevertheless, the increasing

participation of migrant workers in the services sector stems from the low-cost, unskilled segment of the labour demanded. Typically, the migrant workers in this sector are employed in restaurants, hotels and as domestic maids. Domestic maids account for slightly more than 50 per cent of the total foreign labour employed in the services sector. The foreign workers employed in restaurants and as domestic maids work very long hours (18 hours is not unusual in many restaurants), without medical benefits and with no leave. Under these terms of employment and at the wage rate that is offered to migrant workers it is impossible to find locals who are willing to supply their labour. This explains why the number of domestic maids has increased sharply from 75,300 persons in 1997 to 261,006 persons as at July

18

2004.

There is a slight change in the landscape of migrant workers with the excess demand for highly skilled and knowledge-intensive workers. This is a fairly recent category that has come up with Malaysias own development towards being a knowledge economy. However, this is a small segment of the migrant labour supply, and at present accounts for about three per cent of the migrant workers in the country. These workers, or expatriates, are professionals and highly skilled workers who are typically employed in the technical aspects of manufacturing, the oil and gas (O&G) industry, construction and services. A significant number of expatriates supply the labour needs of the more knowledge-intensive sections of the services sector, particularly in health, education and the ICT related industries. For instance, there are 700 expatriates employed in the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC), 70 per cent of whom are software developers, systems analysts, web designers and systems engineers. Similarly, there are 711 expatriates employed in Malaysias public hospitals (as at 2004), 478 of whom are medical officers and 233 of whom are medical specialists.

The highly skilled or knowledge-intensive migrant workers constitute a different section of the foreign labour supply and cannot be lumped together with other migrant workers. One of the distinguishing features of expatriate workers is that they are paid competitive salaries and have the liberty of entering or leaving the labour market on their free will. Secondly, expatriates receive all the benefits of employment (leave, medical benefits, relocation costs, EPF) that locals enjoy. Thirdly, they do not depress the wages in their segment of the labour market, and so are not guilty of distorting the labour market. These being some of the features that separate them from the unskilled migrant workers a separate treatment of the issues relating to their employment is called for; the impact of expatriate employment on the labour market would require a different study.

The picture of migrant labour that emerges - and one that is of concern - is that of workers with low endowments who are subject to the vagaries of unscrupulous

19

employers. These workers have low endowments in the sense that they have little or no education, are unskilled, and are willing to undertake tedious and hazardous jobs. Nevertheless, the wages that these workers would earn in Malaysia would be in excess of what they could earn in the labour markets in their respective countries; this explains the push to seek employment in Malaysia. From the point of view of the employers, jobs that require no skills can profitably be performed by migrant workers who require low payments, and it is to the employers advantage, since the local labour force is averse to doing such work. The presence of weak institutional conditions such as lax enforcement, laws that can be circumvented, difficult border controls and corruption allows for the entry of illegal foreign workers, which doubly works in the favour of employers. The availability of illegal workers depresses the wages that need to be paid to foreign workers, distorts the labour market, and sends signals that result in the misallocation of resources, possibly thwarting the long-run development of the economy.

The foregoing account of trends in migrant labour inflow suggests that migrant labour is used as a buffer to cushion excess demand for labour, when the need for it arises. Further, the ad hoc and inconsistent manner in which policies on migrant labour have been formulated lend credence to this argument. The supply of migrant labour is treated as a reserve army of surplus labour that is drawn upon on occasions of shortage for unskilled labour. The economic conditions in

neighbouring countries, particularly Indonesia, allow this, because the low wages and conditions of poverty serve as push factors for workers to seek employment, even if it be illegal, in Malaysia. As we have observed, the number of migrant workers in Malaysia increases when there is high economic growth and conversely decreases when the economy is under duress. This was most obvious after the 1997 economic crisis that affected Malaysia.

Using migrant labour as buffer has its advantages and problems. One obvious advantage of the strategy of using migrant labour as a reserve of surplus labour is that it helps to keep wage rates down. This is not a strategy that is openly

20

acknowledged. The point that domestic workers are not keen on performing certain jobs is highlighted by firms in lobbying for the need to allow easy access for migrant workers. Second, having a readily available surplus at hand helps to relieve labour shortages when they occur; it facilitates a smoother and more rapid return to labour market equilibrium. The disadvantages to the labour reserve policy merit attention. First, using migrant workers as agents to depress the domestic labour market tends to lead to the exploitation of foreign workers. Second, upholding a reserve migrant labour policy sends incorrect signals about the state of labour supply and it can have a distortionary effect on the allocation of resources.

ASPECTS OF THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF MIGRANT LABOUR

As we have seen in a previous section, there is considerable participation of migrant labour in the agriculture, manufacturing, construction and services sectors in jobs that do not require education or a high level of skills. A detailed

breakdown of the jobs within each sub-sector with the share of participation of migrant labour is not available. This hampers any analysis of the impact of migrant labour on the economy, especially when it comes to the involvement of migrant labour on an industry-wise study; it becomes difficult to be specific about industries or types of jobs where migrant workers predominate.

Nonetheless, the figures that have been presented earlier indicate the broad participation of migrant labour across the key sectors. It is clear that the

Malaysian economy is hugely dependent on migrant labour. Kanapathys (2004) study makes the extent of this dependence abundantly clear when she attempts to trace the impact of a reduction in migrant labour on the economy. The

counterfactual that she poses is: what if there is a 20 per cent repatriation of migrant workers. Kanapathys simulation suggests that the consequences of such an outflow of labour could have deleterious effects on the macroeconomy. It is assumed that this proportion of migrant workers includes unskilled and semi-

21

skilled workers, whose departure would raise the average real wage in the economy by 0.5 per cent. The consequences are seen to be far-reaching, affecting imports, exports and the terms of trade. Also, the consumption, investments and wage rates would be affected. Naturally, there would be an impact on the

consumer price index and GDP. As one would expect, and if migrant labour has made a positive contribution to the economy, the exodus of workers would disturb the prevailing equilibrium position. Local labour being more expensive, the

outward flow of migrant workers would raise the average real wages by 0.5 per cent in Kanapathys model. The higher wage rates would, in the first instance, affect Malaysias external sector, given the predominance of foreign workers in export-oriented sectors. This is estimated to raise export prices by 0.1 per cent, and reduce exports by 0.9 per cent. Imports are expected to decline, because Malaysias exports rely heavily on imports as inputs. This would result in a depreciation of the ringgit (0.6 per cent), a drop in government demand (1.1 per cent) and declines in real household consumption (0.8 per cent) and total investment (1.4 per cent). The net result of migrant labour repatriation in this model is an estimated 1.1 per cent fall in the GDP as well as mild inflationary pressures. The estimates produced by this simulation exercise closely correspond with the intuitive observation that the economy is, indeed, dependent on migrant labour.

Narayanan and Lai (2005) point out that labour demand in the construction sector has far exceeded the supply of construction workers. In their account, the supply of migrant labour has not been entirely sufficient to meet the rising demand for labour, except in recession years. The excess demand for labour, they claim, has pushed the general wage rate upwards and that in spite of the supply of foreign workers. The foreign workers have had a beneficial role to play in the labour market in so far as the possible dampening effect migrant workers could have played in the face of the upward movement of wages. In other words, the acute shortage of workers stimulated the push towards higher wages, but the availability of migrant workers did not nullify the upswing in wages, only they helped contain the upward movement.

22

Recent trends in wages suggest that salaries being paid to workers in the construction industry have been going up. The number of workers employed in this sector has been sliding down and so has the total wage bill paid. The construction sector has lost the vibrancy that it had in the pre-crisis days, and attempts are being made to revive activity in this sector; but the evidence that is available clearly shows that the annual salary per employee has been on the rise since 1995 (Table 7). In 1995 the average salary per employee was about RM14, 700 as against RM20, 000 in 2002. The law does not favour discrimination against migrant workers in the award of wages and employers are required, by the law, to contribute to the social security scheme for foreign workers employed. Employers are also required to pay the employment levy that is imposed on foreign workers. The actual practise is quite different from that prescribed by the law, particularly with the availability of undocumented workers. The second weakness that runs through the construction industry is the presence of contractors who are not registered as legal entities but to whom work is sub-contracted. These smaller contractors depend heavily on illegal migrant workers.

There are two constraints that are felt within the construction sector: a) an adequate supply of local workers who are willing to work at the prevailing wage rate, and b) local workers who are willing to work under prevailing conditions of work. The latter is a constraint in so far as local workers would expect adequate leave (for example on Sundays, public holidays or when religious festivals are observed), medical and other benefits and they are not generally willing to work beyond the legally stipulated work hours unless adequate reward is given. Even when local workers receive the same wages that are paid to migrant workers, they are more demanding in terms of their rights as workers, and that raises the opportunity cost of employers, who, therefore, prefer to employ foreign labour. These factors equally affect the agriculture sector, particularly in the plantations. It is well-recognised that work in oil palm plantations is tiring and tedious (since one works under the sun), dangerous (because these plantations are infested with snakes and also because when the palm fruit is harvested it could fall and deeply

23

cut ones body) and unattractive (due to the poor accommodation that is provided and the absence of facilities for entertainment or social interaction). Obviously, local labour would demand much more than is presently being paid migrant workers.

There is no published data on the wage rate in the agriculture sector, making it difficult to assess how migrant labour has affected wage levels in agriculture. The next most important sector that employs migrant workers is the manufacturing sector where 20 per cent of all foreign labour finds employment, being next in importance to the agriculture sector that employs about 30 per cent of all nonMalaysians working in the country. The number of workers in the manufacturing sector has been more or less stable since 1999 to the present time, fluctuating narrowly around 148,000. The total wages paid out to the workers in

manufacturing has been rising steadily but slowly (Table 8). The number of employees in this sector was about 13,000 in 1999, rose close to 14,000 in 2001 and was about 15,000 in 2003. The average annual salary per employee was RM18,878 in 2003 from RM15,917 in 1999. There was a five per cent increase in the salary per employee from 1999 to 200, but more recently the growth in salary has been more sedate, increasing by 2.5 per cent from 2002 to 2003.

The manufacturing sector employs a large number of migrant workers. The profile of migrant labour in the manufacturing sector is not quite similar to that of the agriculture or services sectors for two reasons. First, there is a large number of Bangladeshis in this sector unlike in the other sectors where the bulk is made up of Indonesians with little education and no skills. Second, many of the foreign workers are semi-skilled. As in the other sectors the supply of migrant workers has kept a cap on wage increases besides relieving the acute labour shortage. Many sub-sectors such as furniture manufacturing, and the production of machinery and steel products depend on migrant labour, although their presence in the manufacturing sector is well spread out and is not restricted to these sectors. The manufacturing sector, being export-oriented and an important (if not crucial) driver of economic growth in Malaysia, carries the key to the countrys economic

24

development. It follows that an adequate supply of labour to this sector as well as stable wage rates are important for the macroeconomic stability and growth of the economy.

Another sector where the migrant workers play an important role is in the services sector. Here they are important for the hotels and restaurants sub-sector and also as maids (Table 9). Five per cent of foreign workers are in the hotels and restaurants sub-sector. The number of domestic maids has been increasing very rapidly. While in 2004 there were at least 261,000 maids, in 1997 there were only about 75,000 foreign workers in this employment category, implying a 300 per cent increase. The presence of female foreign workers in Malaysia has an

interesting influence on the gender structure of domestic labour utilisation since a large number of women would not be able to take up employment in the labour market if not for these domestic maids. The availability of a supply of females as maids releases Malaysian women from their commitment to domestic chores and seek paid employment. The lack of facilities that are provided by the public and private sector employers for the care of children would otherwise constrain the present flexibility in substituting time spent in performing household tasks to accepting paid employment. The contribution of Malaysian women to GDP

would be lower without female migrant workers, although statistical estimates are not available to fix a range on the shortfall that could result.

All in all, it is strikingly clear that the Malaysian economy relies to a very great extent on migrant workers. What is surprising is the lack of a long-term policy on foreign labour given the dependence on migrant workers. This is shocking

because crucial issues seem to be ignored amidst the ad hoc manner in which migrant labour is used (most often) and banned (at times). First, it appears that

ethical issues surrounding the rights of migrant workers have received scant attention. This is a question that will be addressed in the next section. Second, the constant switches in policy decisions suggest that the government is not willing to grapple with the long-term impact of migrant workers. Both these issues jointly imply that no serious thinking has been done to develop a

25

sustainable and consistent policy position on migrant labour in the context of Malaysias own development trajectory.

Before we proceed to discuss the long-term implications of migrant labour it would do well to consider if foreign workers have made any contribution to the productivity growth of the sectors in which their participation is high. The

productivity growth rate in mining was 1.24 per cent in 2000 and 2.11 per cent in 2003, considering the period 2000 to 2003 the average productivity growth has been 1.2 per cent (Table 10). Since 2004 the productivity growth has been slightly higher. For the period 2000-2003 the rate of increase in wages has been higher (as we saw earlier). If even with a supply of migrant labour (which offers a lower opportunity cost than domestic labour) the wage increases are outstripping productivity increases, there is little doubt that the situation would be worse if migrant labour were not available. The productivity growth in services and

manufacturing was relatively high in 2000 (3 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively) and has subsequently been in decline, although it rose in 2006 but not to 2000 levels. In these sectors, too, the growth in wage rates exceeded that of productivity. The same is observed for the construction sector (Narayanan and Lai, 2006). Maintaining a supply of cheap migrant labour has been useful in minimising the extent to which wage increases exceeded productivity increases, although it would definitely have been preferable if the growth in productivity was greater than wage increases.

The profile of jobs that migrant workers have been employed (and continue to be employed) in are those that are no longer attractive to domestic labour. In fact, the local labour force is averse to these jobs since they have other alternative forms of employment (or self-employment). Female foreign workers have been very useful in freeing local women to actively participate in the labour force; and this has helped them contribute to GDP. Further, the expatriation of foreign workers could lead to a decrease in exports and GDP. The supply of migrant

26

labour (legal and illegal) has kept an upper boundary on wage rate increases. The impact that foreign workers have on wage rates is a pivotal issue and constitutes the central mechanism through which the effect of the supply of foreign labour expresses itself on the Malaysian economy.

The relatively low wages that are possible with migrant labour, than would otherwise prevail, makes Malaysian exports correspondingly attractive. This

sustains high exports and the resultant GDP and growth rates. A decrease in exports would also affect Malaysias balance of trade and exchange rate status. Also, low wages in the manufacturing and services sectors help, to an extent, keep inflationary pressures under control. Given the alternatives to employment that are available to the local labour force a very much higher wage rate than currently prevails would be necessary to attract them to undertake the jobs that foreign workers are presently employed in. It is hard to imagine locals working in restaurants, as plantation labourers, construction site workers or in non-automated factories involving labour-intensive operations, and definitely not as domestic maids.

The fact that the opportunity cost of employing a migrant worker is lower, to an employer, than employing a local worker with comparable skills does carry with it a distinct, but not immediately recognisable, problem. As has been alluded to in a previous section the less costly supply of migrant labour directs resources to industries in which foreign workers can be procured, and by so doing signals the profitability of these industries. The price signals that emanate from those

markets in which migrant workers are proportionately active are distorted because, as we have mentioned earlier, the full cost of their labour is not paid. This results in the misallocation of resources since investment is directed into those industries with migrant workers. This phenomenon also encourages the inflow of illegal workers. If laws are fully enforced and the rights of workers respected, the wages rates of migrant workers would go up, and so would the prevailing wage rates in those sectors.

27

There is a long-term danger attached with keeping the wages of migrant workers artificially low. The continued supply of migrant labour would create the illusion that labour-intensive methods of production and such industries are profitable. This will encourage the growth of these industries and hamper their industrial upgrading. The Second Industrial Master Plan (IMP2) (Ministry of International Trade and Industry, 1996) envisions industrial development where value-added production predominates; and this complements the development of a knowledgebased economy. This vision continues into the Third Industrial Master Plan (Ministry of International Trade and Industry, 2005) However, promoting the plantation sector, low-technology construction does little to encourage industrial upgrading and the transformation to an economy that is more technology-based. The dependence on migrant labour will delay automation and the decay of labourintensive activities such as agriculture. Clearly, the long-term development of the economy is constricted because of the abundant supply of migrant labour whose costs are not fully paid. There is no problem per se with using migrant labour, but in the Malaysian case it will delay the decay of inefficient economic activities and hamper economic transformation.

SOME ETHICAL ISSUES As we have seen, the government has not taken a consistent and holistic approach towards the design of migrant labour policies. Although there is no doubt that migrant workers have made a positive contribution towards the economic development of Malaysia, there is scant consideration for their rights. This raises ethical issues, which are of intrinsic value; but there are also economic questions that are associated with the disregard for the rights of workers. A poorly

formulated policy on migrant labour with defective enforcement mechanisms encourages the inflow of undocumented workers; it also results in the lack of access to health care, adequate housing, and violations of their human rights. To accord proper work conditions, health care, and housing to migrant workers involve costs; but by not doing so there is the possibility of creating wider problems that come with the spread of disease and the social problems that

28

disenfranchised workers could create.

In recent years the government has launched at least two major operations to penalise undocumented immigrants. One such attempt was made in 2002, in which 450,000 undocumented migrants were repatriated. In 2005 another

400,000 illegal migrants were sent back, although it is estimated that there were 1.2 million undocumented migrants in Malaysia at that time. The Immigration Act (Section 6) allows for migrant workers without adequate documentation to be whipped and imprisoned. Trade unions and non-governmental organisations have raised their concern over the harshness of these penalties (see MTUC 2005, for instance). Rather than to systematically and consistently prevent illegal workers from entering and staying in the country the authorities act harshly at sporadic intervals. The poor enforcement mechanisms have been fully exploited by

employers, and MTUC (2005) notes that, undocumented migrant workers are often forced to work more for less and often without basic facilities such as housing, medical care, overtime payment. As if in justification for its

lackadaisical and irregular enforcement efforts, the government offers the following rationalisation:

Preventive measures to stop illegal workers are very costly, time consuming and involve a large number of enforcement personnel from the Police, Immigration, Armed Forces and RELA. Enforcement operations to reduce illegal workers faced many obstacles, such as space constraint at the twelve detention camps, which can only accommodate about 12,000 detainees at any one time. The

Government spends about RM3-RM4 million per year providing meals to the detainees. (p. 74, Economic Report, 2004/2005)

One of the most frequent violations of labour rights has been the non-payment of wages and unfair dismissal of migrant workers. During the period 2000-2005 MTUC itself handled cases for 1,200 migrants on grounds of non-payment of wages and unfair dismissal. The immigration process does not permit even

29

documented foreign workers to pursue their grievances through the Labour Court because the Immigration Department does not offer visas for such reasons. When migrant workers are known to initiate legal proceedings against their employers the employers cancel their work passes which renders the migrant workers undocumented.

Second, most migrant workers do not have employment contracts and are not aware of the need for contracts. The fact that migrant workers are issued work permits that allow them to be employed by a particular employer allows abuse since they are not able to seek alternate employment when cheated by employers. It has been observed that the contract presented to migrant workers on arrival in Malaysia is less favourable than that agreed upon prior to their departure from their home country.

Illegal or undocumented migrant workers do not have any access to health care services because they fall within the informal sector. The same is the case with domestic maids, who, though legally employed, do not have the support of association or employment contracts. In fact, legal migrant workers are not betteroff in regard to their access to health care, because as Verghis (2005) notes the Malaysian health policy presumes that migrants place a burden on an over stretched public health services system. She goes on to elaborate that migrants admitted to public hospitals pay first class fees, but will be entitled only to third class treatment, a practise that is unfair and blatantly discriminatory.

Migrant workers are deprived of their rights as workers. The absence of adequate on-site inspection by appropriate officers and the ineffective enforcement of the law have led to continued abuse of the rights of migrant workers. Nelson (2007) notes that some of the violations of migrant workers rights include the absence of any off days, long working hours and bad living and working conditions. Migrant workers often have limited freedom to interact as they choose and are often isolated from the outside world. Employers often withhold the visas and travel documentation of migrant workers, making them, technically, undocumented

30

workers, which leaves them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, even sexual abuse from enforcement officers.

Obviously, the rights of migrant workers have been ignored and it necessary that they be addressed since they have economic consequences. Perhaps at the

broadest level Malaysias commitment to the rights of migrant workers can be affirmed as a first step. Malaysia has not ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and this is perhaps an issue that needs to be examined more closely. Second, the government needs to play a firmer role as a regulatory agent in the inflow of migrant workers. There is considerable abuse that comes about from the unregulated recruitment of foreign workers, which at present is done by private agents. The unscrupulous practises of employment agencies have led to foreign workers being stranded and without being able to find employment. A firmer policy on recruitment is required. Finally, more active execution of inspection and enforcement is essential.

CONCLUDING REMARKS As Malaysias industrialisation process has deepened, its reliance on migrant labour has increased. Malaysias industrialisation programme has produced two effects: a) the rural-urban migration of local labour and b) the withering of the agriculture sector. The agriculture sector has, consequently, come to be seen as unattractive, both in terms of wages and in terms of work conditions. This has created excess demand for labour in the agriculture sector, particularly in the plantations. On the other hand, the greater emphasis on export-oriented

manufacturing has also created acute shortages of labour. This has been felt, to an increasing extent, in the manufacturing sector, but it is a phenomenon that is also encountered in the construction and services sectors. At any rate, the net result is increasing demand for migrant workers.

As the evidence indicates, Malaysia has had a continuous inflow of migrant

31

workers, and their contribution to the economy is important. Nevertheless, the record of events suggests that the governments policies on migrant labour have been piecemeal in the sense that the policy responses are directed at exigencies at particular junctures in the economy. One of the problems appears to be a lack of policy consistency that is driven on one hand by felt need for migrant labour. On the other hand there is the reluctance to be overly dependent on foreign workers as well as responses to downturns in the economy that trigger adjustments in the demand for labour. The presence of foreign labour that can be easily repatriated facilitates these labour market adjustments.

Migrant labour does make a positive contribution to the economy at present in that it fills those jobs that are unattractive to local labour. Besides, foreign workers help to keep a limit on upward wage spirals and they encourage local women to participate in the labour market. But the continued presence of migrant labour does have possible negative consequences. First, the supply of foreign workers results in the misallocation of investments. Second, the availability of relatively cheap (foreign) labour delays technological progress at the firm-level, and thus slows the long-term industrial upgrading of the economy.

What is perhaps most worrying is the relative neglect for the rights of foreign workers. A policy on migrant labour that acknowledges that migrant workers have human rights would be useful both intrinsically as well as in terms of the economic outcomes it would generate. The lack of strict enforcement of regulations encourages the abuse of foreign workers by employers and recruitment agencies. Further, it is necessary to devise policies and implementation

procedures with explicit concern for the rights aspect of migrant workers. This will not only safeguard the rights of workers, but it will also allay the threat of social problems and mop up the excess surplus that employer enjoy through the employment of migrant workers.

REFERENCES

32

Department of Statistics 2006 Yearbook of Statistics, Department of Statistics, Kuala Lumpur Kanapathy, V. 2004 Economic Recovery, the Labour Market and Migrant Workers in Malaysia, Paper prepared for the 2004 Workshop on International Migration and Labour Markets in Asia, organised by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, Tokyo Kanapathy, V. 2006 Migrant Workers in Malaysia: An Overview, paper prepared for the Workshop on an East Asian Cooperation Framework for Migrant Labour, organised by the Network of East Asian Think Tanks (NEAT), 6-7 December, Kuala Lumpur Ministry of International Trade and Industry 1996 Second Industrial Master Plan: 1996-2005, Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Kuala Lumpur Ministry of International Trade and Industry 2005 Third Industrial Master Plan: 2006-2020, Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Kuala Lumpur Ministry of Finance, Economic Report (Various issues), Ministry of Finance, Kuala Lumpur Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) 2005 Country Report: Migrant Workers Situation in Malaysia: Overview and Concerns, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, Tokyo National Productivity Corporation (NPC), 2006 Productivity Report 2006, National Productivity Corporation, Kuala Lumpur Narayanan, S. and Y-W Lai 2005 The Causes and Consequences of Immigrant Labour in the Construction Sector in Malaysia International Migration, Vol. 43 No. 5 Navamukundan, A. 2002 Labour Migration in Malaysia Trade Union Views, in Labour Education 4/2002, No. 129, ILO (http://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/actrav/publ/129/)

33

Nelson, N.C. 2007 Gender, Migration and HIV: Impact on Women in the Context of International Political Economy, Mimeo, CARAM Asia, Kuala Lumpur The Star 2007 Tey, N.P. 1997 Policy change on Foreign Workers Irks Employers, 4 October Migration Issues in the Asia Pacific: Issues Paper from Malaysia in P. Brownlee and C. Mitchell (1997), Migration Issues in the Asia Pacific, Working Paper No.1, UNESCO-MOST and Asia Pacific Migration Research Network (APMRN). Policy Issues and Concerns with Regards to Migrant Health in Malaysia, Paper prepared for the Roundtable on Migration and Refugee Issues organised by UNHCR, Kuala Lumpur, 13-14 June.

Verghis, S. 2005

34

Table 1 Labour Force, Unemployment and Unemployment Rate in Malaysia 1980-2006 Unemployment Rate % 5.6 4.7 4.6 5.2 6.3 6.9 8.3 8.2 8.1 7.1 6.0 5.6 3.7 3.0 2.9 3.1 2.5 2.4 3.2 3.4 3.1 3.6 3.5 3.6 3.5

Labour Force 000 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1990 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 5,380 5,020 5,140 5,250 5,380 6,039 6,222 6,409 6,622 6,834 7,047 7,258 7,461 7,627 7,834 8,257 8,641 9,038 8,881 9,178 9,573 9,724 10,064 10,426 10,846 % Change 3.1 -6.7 2.4 2.1 2.5 12.2 3.0 3.0 3.3 3.2 3.1 3.0 2.8 2.2 2.7 5.4 4.7 4.6 -1.7 3.3 4.3 1.6 3.5 3.6 4.0

Unemployment 000 563 271 276 336 360 414 515 528 534 444 218 217 211 129 155 258 215 221 284 308 301 345 355 379 382

35

2005 2006

11,291 11,544

4.1 2.2

396 385

3.5 3.3

Source: Economic Report, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia (1980/1981 - 2007/2008)

36

Table 2 Malaysia: GDP by Sector, 1970-2005 (% share) Sectors Agriculture Mining Manufacturing Construction Total services Business Services Government services Total 1970 33.6 7.2 12.8 3.8 42.6 23.3 19.3 100.0 1980 22.2 9.2 20.2 4.5 43.9 30.9 13.0 100.0 1990 16.3 9.4 24.6 3.5 46.1 37.3 8.8 100.0 1995 10.3 8.2 27.1 4.4 50.0 42.9 7.1 100.0 2000 8.9 7.3 31.9 3.3 48.6 41.8 6.8 100.0 2005 8.2 6.7 31.6 2.7 50.8 43.3 7.5 100.0

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia

37

Table 3 Malaysia: Employment by Sector, 1970-2005 (% share) Sectors Agriculture Mining Manufacturing Construction Total services Business services Government services Total 1970 53.5 2.6 8.7 2.7 32.5 16.8 15.7 100.0 1980 39.7 1.7 15.7 5.6 37.3 23.6 13.7 100.0 1990 27.7 0.7 19.5 6.4 45.7 32.9 12.8 100.0 1995 18.7 0.5 25.3 9.0 46.5 35.4 11.1 100.0 2000 15.2 0.4 27.6 8.1 48.7 38.1 10.6 100.0 2005 12.0 0.4 29.5 8.1 50.0 40.2 9.8 100.0

Source: Economic Planning Unit

38

Table 4: Employment in various sectors in Malaysia from 1980 to 2006

Agriculture '000 1,911 1,934 1,929 1,925 1,932 1,760 1,807 1,876 1,908 1,833 1,889 1,833 1,738 1,680 1,585 1,493 1,492 1,468 1,401 1,427 1,408 1,406 1,405 1,402 1,397 1,386 1,392 % -7.1 1.2 -0.3 -0.2 0.4 -8.9 2.7 3.8 1.7 -3.9 3.1 -3.0 -5.2 -3.3 -5.7 -5.8 -0.1 -1.6 -4.6 1.8 -1.3 -0.1 0.0 -0.2 -0.3 -0.8 0.5 Mining '000 80.0 76.0 69.0 66.0 67.0 44.0 37.0 37.0 37.0 33.0 29.0 33.0 37.0 36.0 36.0 40.5 41.0 41.7 42.2 41.7 41.2 40.9 41.2 41.7 42.2 42.6 42.6 % -11.1 -5.0 -9.2 -4.3 1.5 -34.3 -15.9 0.0 0.0 -10.8 -12.1 13.8 12.1 -2.7 0.0 12.5 1.2 1.7 1.2 -1.2 -1.2 -0.7 0.7 1.2 1.2 0.9 0.0 Manufacturing '000 755 787 799 815 844 855 861 921 1,013 1,171 1,333 1,470 1,639 1,742 1,892 2,028 2,230 2,375 2,277 2,343 2,558 2,461 2,519 2,698 2,870 2,990 3,244 % 0.0 4.2 1.5 2.0 3.6 1.3 0.7 7.0 10.0 15.6 13.8 10.3 11.5 6.3 8.6 7.2 10.0 6.5 -4.1 2.9 9.2 -3.8 2.4 7.1 6.4 4.2 8.5 Construction '000 270 299 318 340 349 429 382 355 356 377 424 465 507 544 598 717 796 876 810 749 755 770 770 780 771 775 755 % 10.7 10.7 6.4 6.9 2.6 22.9 -11.0 -7.1 0.3 5.9 12.5 9.7 9.0 7.3 9.9 19.9 11.0 10.1 -7.6 -7.5 0.8 2.0 0.1 1.2 -1.2 0.6 -2.6 Services '000 1,801 1,924 2,026 2,105 2,190 2,536 2,620 2,693 2,773 2,976 3,154 3,240 3,329 3,496 3,568 3,721 3,868 4,057 4,067 4,310 4,509 4,702 4,974 5,126 5,384 5,701 5,725 % 1.2 6.8 5.3 3.9 4.0 15.8 3.3 2.8 3.0 7.3 6.0 2.7 2.7 5.0 2.1 4.3 3.9 4.9 0.2 6.0 4.6 4.3 5.8 3.1 5.0 5.9 0.4

1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

39

Source: Economic Report, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia (1980/1981 2007/2008)

40

Table 5 Composition of Foreign Workers by Country of Origin (%) 1998 Indonesia Nepal Bangladesh India Myanmar Philippines Thailand Pakistan Others Total 53.3 0.1 37.1 3.6 1.3 207 0.7 1 0.2 100 1999 65.7 0.1 27 3.2 0.9 1.8 0.5 0.6 0.2 100 2000 69.4 0.1 24.6 3 0.5 1.2 0.4 0.5 0.3 100 2001 68.4 7.3 17.1 4 1 1 0.4 0.4 0.4 100 2002 64.7 9.7 9.7 4.6 3.3 0.8 2.4 0.2 4.6 100 2003 63.8 9.7 8.4 5.6 4.3 0.6 0.9 0.2 6.5 100 2004 66.5 9.2 8 4.5 4.2 1.1 1 0.1 5.4 100

Source:Department of Immigration

41

Table 6 Estimates of Registered Migrant Workers (Skilled and Semi-skilled)

Year 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

No. of Workers 532,723 642,057 726,689 745,239 1,471,562 1,127,652 897,705 799,685 807,984 n.a. n.a. 1,359,500 1,944,646

42

Table 7 Salaries per employee (Construction industry)

No. of employee

Salaries and wages paid (RM million)

Salary per employee (RM)

% change 12.65 6.81 7.94 4.99

199 524,457 7,712 14,704.73 5 199 604,453 10,013 16,565.39 6 199 547,509 9,687 17,692.86 8 200 456,711 8,722 19,097.42 0 200 454,274 9,108 20,049.57 2 Source: Yearbook of Statistics, Department of Statistics, Malaysia (2006)

43

Table 8 Salaries per employee (Manufacturing Industry)

No. of employees 1999 2000 2001 2002 1,347,156 1,560,922 1,379,831 1,477,247

Salaries and wages paid (RM million) 21,443 26,123 24,571 27,214

Salary per employee (RM) 15,917.23 16,735.62 17,807.25 18,422.1

% change 5.14 6.40 3.45 2.47

1,490,452 2,137 18,878.16 2003 Source: Yearbook of Statistics, Department of Statistics, Malaysia (2006)

44

Table 9 Salaries per employee (Hotels and others lodging places) No. of employee 1996 1998 2000 2002 68542 69382 82864 80322 Salaries and wages paid (RM thousand) 781739 850475 1082929 1159819 salary per employee (RM) 11405.25517 12257.86227 13068.75121 14439.61804 % change 7.48 6.62 10.49 1.73

78062 1146699 14689.59289 2003 Source: Yearbook of Statistics, Department of Statistics, Malaysia (2006)

45

Table 10 Malaysia: Productivity growth of the economic sector, 2000-2006 Sectors Mining Utilities Finance Transport Manufacturing Trade Other services Govt. services Agriculture Construction GDP 2000 1.24 3.86 2.5 3.76 11.05 2.37 2.87 4.95 0.52 2.33 8.5 2001 -0.38 2.53 4.93 2.12 -3.42 1.54 0.13 3.52 2.29 0.39 0.4 2002 1.9 2.93 2.75 1.35 3.32 1.14 1.03 3.36 1.11 2.51 4.24 2003 2.11 3.12 2.81 2.15 5.31 3.24 2.12 3.37 1.92 2.55 5.2 2004 3.57 2.9 2.4 3.2 6.1 2.4 1.76 3.3 2.5 -0.3 7.1 2005 1.65 4.92 3.86 4.03 3.76 2.67 1.19 3.35 2.58 -0.74 5.3 2006 1.79 4.52 4.06 4.07 4.42 2.15 1.51 3.42 3.41 0.47 5.9 Average 1.70 3.54 3.33 2.95 4.36 2.22 1.52 3.61 2.05 1.03 5.23

Source: Productivity Report, National Productivity Corporation, Malaysia (2000 2006)

46

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Discussion On Contract Labour Act 1970Document28 pagesDiscussion On Contract Labour Act 1970AniruddhShastreePas encore d'évaluation

- Types of ContractDocument5 pagesTypes of ContractSarah KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iron Lady: Group ProjectDocument35 pagesThe Iron Lady: Group ProjectMourad LamghariPas encore d'évaluation

- Sale of Goods and Partnership Act (Contract II)Document172 pagesSale of Goods and Partnership Act (Contract II)holly latonPas encore d'évaluation

- Narbada Devi Gupta Vs. Birendra Kumar Jaiswal Supreme Court Rent Receipt CaseDocument4 pagesNarbada Devi Gupta Vs. Birendra Kumar Jaiswal Supreme Court Rent Receipt CasePrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act 1970Document14 pagesContract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act 1970Anmol JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Dispute Act 1947Document16 pagesIndustrial Dispute Act 1947Mohit Shukla100% (1)

- INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION: GRADUAL VS. DISCONTINUOUS CHANGEDocument13 pagesINDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION: GRADUAL VS. DISCONTINUOUS CHANGERaymund FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment II ContractDocument7 pagesAssignment II ContractriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case LawsDocument24 pagesCase LawsRicky Chodha100% (1)

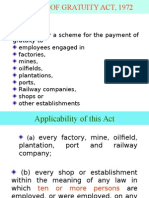

- Payment of Gratuity Act-1972Document35 pagesPayment of Gratuity Act-1972Ramesh KannaPas encore d'évaluation

- ConstiDocument202 pagesConstiFrancess Mae AlonzoPas encore d'évaluation

- Change and Transformation in Asian Industrial Relations: Sarosh Kuruvilla and Christopher L. EricksonDocument57 pagesChange and Transformation in Asian Industrial Relations: Sarosh Kuruvilla and Christopher L. EricksonPrincessClarizePas encore d'évaluation

- Regulation of Contract Labour in IndiaDocument14 pagesRegulation of Contract Labour in IndiaRobertPas encore d'évaluation

- LiberalizationDocument47 pagesLiberalizationmayankjain_17100% (1)

- HRM ReviewerDocument3 pagesHRM ReviewerPinks D'CarlosPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Globalisation On Industrial Relations: January 2013Document21 pagesImpact of Globalisation On Industrial Relations: January 2013Mohammed sameh RPas encore d'évaluation

- Petition For DivorceDocument4 pagesPetition For DivorceVivek SaiPas encore d'évaluation

- AIRLINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION VS PHILIPPINE AIRLINESDocument4 pagesAIRLINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION VS PHILIPPINE AIRLINESRudith ann QuiachonPas encore d'évaluation

- IpcDocument11 pagesIpcMamta BishtPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 18 Domestic Enquiry: ObjectivesDocument10 pagesUnit 18 Domestic Enquiry: ObjectivesgauravklsPas encore d'évaluation