Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Rol de Los Antibióticos en El Tratamiento de La Rinosinusitis Aguda en La Niñez

Transféré par

Alcibíades Batista GonzálezDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Rol de Los Antibióticos en El Tratamiento de La Rinosinusitis Aguda en La Niñez

Transféré par

Alcibíades Batista GonzálezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

www.medscape.com

The Role of Antibiotics in the Treatment of Acute Rhinosinusitis in Children

A Systematic Review

Michael John Cronin, Sami Khan, Shakir Saeed Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(4):299-303.

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Objective A systematic review of randomised controlled trials reporting the efficacy of antibiotics compared with placebo in the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis in children. Design Systematic review and meta-analysis. Data sources Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, Embase and references obtained from retrieved articles. Results Four studies fitted the selection criteria for inclusion. Risks for internal bias were thought to be small for each study, but external bias is potentially significant. The pooled OR for symptom improvement at 1014 days favouring the use of antibiotics was 2.0 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.47; I2=14.8%). Conclusions While the meta-analysis provides evidence to support the use of antibiotics for acute rhinosinusitis in children, it is the assessment of this review that such efficacy has not been adequately demonstrated. There remains a clear methodological challenge in the examination of this important clinical question; this challenge relates to difficulties in the application of appropriate diagnostic and inclusion criteria which are also consistent between studies.

Introduction

Acute rhinosinusitis (defined here as rhinosinusitis lasting less than 30 days)[1] results from inflammatory processes involving mucosal membranes and secretions within the paranasal sinuses, and is generally associated with some obstruction of sinus drainage. The inflammation may be caused by pathogens (bacterial, virus or fungal), by allergic reactions, chemical irritants, foreign bodies or a variety of other systemic disorders.[25] The maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are present at birth, but small. The sphenoid and frontal sinuses pneumatise later between 5 and 8 years of age.[1] Sinus infections may occur in children younger than 1 year, but this is rare. A synonymous term, sinusitis, is still used in the literature, however, sinus involvement is usually a complication of a viral upper respiratory infection, and given the contiguity of sinus and nasal mucosa, rhinosinusitis has become the internationally accepted term.[6] The frequency of this condition remains unclear largely due to practical difficulties in identifying the extent and site of inflammation in any one instance.[5] Children are estimated to experience between 6 and 8 upper respiratory infections each year (adults 23), of which 513% may be complicated by bacterial rhinosinusitis (adults 0.52%).[1 7] Complications of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) can be serious and include orbital or periorbital cellulitis, subdural or epidural empyema, brain abscess and osteitis.[8] Imaging of the sinus cavities (CT, MRI, x-ray, ultrasound) may provide evidence for the presence of inflammation, and direct aspiration of secretions from within sinuses may identify causative pathogens, but neither of these two forms of investigation are routinely requested, reliable or indeed available especially in the context of primary care.[1 6 911] Symptoms and signs ascribed to sinusitis include headache, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, sneezing, otalgia, daytime cough, pyrexia, localised tenderness, localised oedema, malodorous breath, sore throat and altered sense of smell. Symptoms in children tend to be a little different from those occurring in adults; nasal discharge and cough are common, whereas headache,

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 1/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

localised oedema and tenderness are rare findings. While these symptoms are non-specific they are usually taken in combinations to suggest a diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis, but these are not always consistently applied.[1 1014] The diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis, especially ABRS, remains a clinical challenge. Whilst the majority of upper respiratory infections are caused by viral agents, and generally, self-limiting the use of antibiotics as a treatment remains high.[15] The economic costs of these treatments are significant.[16] A recent review of antibiotic prescribing trends in the USA over a 10-year period has shown little change in the frequency of antibiotics prescribed for children with acute rhinosinusitis (about 75% of children diagnosed were prescribed antibiotics).[17] This practice, favouring the use of antimicrobials, is relatively more supported by published North American guidelines, and acute rhinosinusitis is reported as the fifth leading reason for antibiotic use in children.[1 18 15] In the UK there is some evidence to suggest that antibiotic prescribing for acute rhinosinusitis is also relatively high.[19] UK guidelines, however, advise that antibiotics should be preserved for those children who are considered to be more severely ill, but otherwise to be generally avoided, acute rhinosinusitis being perceived as a self-limiting condition.[6 20] It should be noted that UK and North American guidelines differ fundamentally; the former provide recommendations for acute rhinosinusitis whatever the assumed aetiology, whereas, the latter specifically attempt to apply diagnostic criteria to define ABRS (see ). All guidelines have drawn attention to the emerging risk of antibiotic resistance.

Table 1. Current North American, European and UK guidelines providing recommendations for antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in children

Guideline

Diagnostic criteria

Antibiotic recommendation

American Academy of Paediatrics (2001)1 Infectious Diseases Society of America (2012)18 NICE (2008)6 NHS Evidence (CKS NICE) (2012)20

Severity tool to predict ABRS (persistence, severe symptoms) Severity tool to predict ABRS (persistence, not improving, severe symptoms, doublesickening) (No diagnostic criteria provided)

Antibiotics to be prescribed if criteria for ABRS met Antibiotics to be prescribed if criteria for ABRS met Antibiotics not advised unless seriously ill, localised complications, high-risk comorbidities

Antibiotics not advised unless General symptoms defining acute seriously ill, localised complications, rhinosinusitis high risk comorbidities

EPOS (European position Antibiotics to be prescribed if General clinical findings defining paper on rhinosinusitis symptoms severe or increasing after acute rhinosinusitis 21 and nasal polyps 2012) 5 days, comorbidity, complications

ABRS, acute bacterial rhinosinusitis; CKS, Clinical Knowledge Summaries; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. A Cochrane review first published in 1995 and updated in 2002 concludes that there is no good evidence for the routine prescribing of antibiotics in children with acute rhinosinusitis.[22] A further systematic review of antibiotic versus placebo for acute rhinosinusitis was published in 2008; this examined antibiotic efficacy principally in the adult population but did include three randomised controlled trial (RCTs) involving children.[23] The reviewers concluded that there was some evidence, although limited, to support the use of antibiotics. Most recently, a Cochrane review of RCTs in adults (this included trials in which there were less than 20% of participants under the age of 18) produced a more cautious statement to the effect that antibiotics did help some people a little, but overall made very little difference to most.[24] There is, thus, variation both in practice and in assessments of the evidence. It would be true, perhaps, to say that medical practitioners in Europe and the UK are more likely to be conservative in their management of children with

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 2/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

perceived acute rhinosinusitis than their counterparts in North America. The aim of this study is to provide a systematic review of the current evidence for the efficacy of antibiotics in the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis in children.

Methods

Searches

We searched Medline, Embase and the Cochrane controlled trials register up to October 2011 using the terms sinusitis, paranasal, rhinosinutis, purulent, rhinorrhea, sinus infection, randomised, randomised control trial, double blind method, random allocation, placebo, antibiotic, antimicrobial, animal, human, child, children and adolescent. No restriction was made based on language. MC, SK and SS each independently conducted a literature search and assessment for inclusion. We contacted authors where relevant data was not available in published sources.

Selection

Studies were included if the following criteria were all met: involving children between the ages of 1 and 18 years; a randomised control study involving patients diagnosed to have either acute sinusitis or acute rhinosinusitis; the efficacy of antibiotics compared with placebos; analytical data available for children less than 15 years of age (this was to capture those studies which included both adults and patients less than 18 years old, but also children in younger age groups). We chose 30 days as the maximum symptom duration to exclude patients who may be defined to have chronic rhinosinusitis.[1] Studies included needed to describe a primary outcome of symptom improvement following the intervention. Evaluation and quantitative analysistwo authors, MC and SS, independently assessed the included trials for quality. This assessment was based on the methodological approach outlined by the Cochrane collaboration.[25] Any disagreements between the two reviewers was resolved by discussion and consensus. STATA 10.0 was used for the meta-analysis of outcome data.[26] A random effects model was applied using ORs and 95% CIs. An I2 statistic for heterogeneity was applied to the pooled ORs.

Results

Search Results

Ninety-six articles were identified in the search for inclusion; following screening and eligibility assessment, 84 articles were excluded on the basis of title and abstract alone (reasons for exclusion included: repeat citation24, not a RCT30, children not included8, not acute rhinosinusitis26, not antibiotic vs placebo29). Twelve studies were included for full text scrutiny.[2738] Of the 12 studies subject to full text scrutiny, only four fulfilled all the selection criteria.[2730] A further two publications were considered for inclusion, both were RCTs conducted principally involving adult patients, but included patients less than 15 years of age,[31 32] unfortunately, no replies have been received on writing to the lead authors requesting a breakdown of data for patients aged less than 18 years. Of the remaining six publications not fulfilling selection criteria; two included patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, one was a repeat publication of an earlier RCT, and three included adult participants only or subjects older than 15 years of age.

Study Characteristics and Appraisal

Two reviewers (SS and MC) independently assessed each of the four RCTs for quality and potential bias. The assessment was based on the methodological process outlined by the Cochrane collaboration.[25] Internal bias was evaluated using the described quality rating scale (randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, outcome reporting and other sources of bias). Sources for potential external bias were analysed. Data was extracted relating to diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, definition of outcomes, treatment protocols and study results. This data is summarised in .

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 3/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

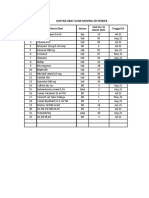

Table 2. Summary of findings from included studies

Name

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes

Potential bias

Wald 1986

Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score and sinus radiographs. Symptoms for minimum of 10 days. Exclusion of patients with +ve grp A streptococci swabs.

216 years seen at primary or secondary services. Attrition to 93 patients out of 136. Amoxicillin (30); amoxicillinclavulonate (28); placebo (35). 118 years seen at primary care centres. 161 included: amoxicillin (58); amoxicillinclavulonate (48); placebo (55). 410 years seen at primary health centre. Attrition to 72 patients out of 82 enrolled. Cefuroxime (35); placebo (37). 110 years seen at primary and secondary centres. 56 patients

Randomisation Intervention Outcomes assessed at method not period10 3 and 10 days. described. No days. Children receiving intention to treat Amoxicillin 40 either antibiotic method. No detail mg/kg/d in statistically more likely regarding possible divided doses to be cured at 3 and use of ancillary in both 10 days (p<0.01 and drugs. Use of sinus amoxicillin <0.05 respectively). radiographs and in Adverse effects: decreases external amoxicillindiarrhoea (5 antibiotic; validity.Cochrane clavulonate 1 placebo); rash (1 Collaboration 6 groups. antibiotic; 1 placebo). domain tool: Low risk of bias. Intervention period14 days. Amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/d in divided doses. Amoxicillin, in amoxicillinclavulonate, 45 mg/kg/d in divided doses. Outcomes assessed at 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28 and 60 days. No difference in patient outcomes between groups. Symptoms improved over time for all groups with no significant difference (p=0.80). Adverse effects gastrointestinal or rash (antibiotic group 16, placebo 5).

Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score. Symptoms for minimum of 10 Garbutt days. Exclusion 2001 of patients with fulminant/severe disease or concurrent illness; symptoms >28 days Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score and sinus ultrasonography. Exclusion of patients with concurrent illness or treatment; symptoms >3 weeks Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score. Exclusion of patients with

Possible bias with exclusion of patients with more severe disease.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bias.

Kristo 2005

Primary outcome assessed at 14 days. No significant Intervention difference noted period10 between 2 groups. days. 'Cure' in antibiotic Cefuroxime group 63% and 125 mg twice placebo group 57%. daily. Adverse effects: diarrhoea (1 antibiotic; 2 placebo).

No intention to treat model. Use of sinus ultrasonography decreases external validity.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bias.

Wald

Primary outcome Intervention assessed at 14 days. period14 Significant more days (?). 'cures' in the antibiotic Amoxicillin, in group (14) than

No detail regarding possible use of ancillary drugs. Intended sample

4/11

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

2009

symptoms >30 days; concurrent illness or treatment; acute sinusitis complications.

enrolled; amoxicillinclavulonate (28), placebo (28).

amoxicillin clavulonate, 90 mg/kg/d in divided doses.

placebo group (4) (p=0.01). Adverse effects mostly diarrhoea (12 antibiotic; 4 placebo).

size not attained.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bia

Quantitative Analyses

The quantitative analysis has assessed improvement in symptoms at 14 days from commencement of treatment (10 days for the study reported by Wald 1986). The results of the meta-analysis of outcome data (figure 1) suggest a benefit for those participants treated with antibiotics with the pooled statistic giving an OR of 2 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.47 and estimated predictive interval 0.439.26). The I2 statistic would suggest moderate to substantial heterogeneity. The number needed to treat (NNT) for the pooled data is 8 (varying between 3 and 50 for the individual trials); this is the NNT for an improvement in symptoms for those treated with antibiotics compared with placebo.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of antibiotic versus placebo, where the outcome measured is improvement of symptoms at 14 days (exception Wald 1986 where outcome assessed at 10 days).

Discussion

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 5/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

This review of four RCTs comparing antibiotic and placebo in the management of acute rhinosinusitis would suggest to us that there is some but nevertheless insufficient evidence to support the routine use of antibiotics. Each of these RCTs was, in our opinion, well conducted, but not without small risk of internal bias. Two RCTs do show benefit over placebo in the use of antibiotics. Although both these two RCTs have been conducted by the same principle investigator, there is no evidence that this should detract from the validity of their findings. Adverse reactions, principally gastrointestinal, were nearly three times more common in those treated with antibiotics (a total of 35 reported in the antibiotic groups compared with 13 in those prescribed placebo). No children treated with placebo only are reported to have developed significant complications due to acute sinusitis. The meta-analysis (figure 1) does suggest evidence for the efficacy of antibiotics in the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis. The NNT of 8 (range 350 for individual studies) can perhaps be placed in the context of the NNT data for acute otitis media (AOM) in children quoted in National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommendations for self-limiting respiratory tract infections.[6] Here the NNT values for children less than 2 years with AOM and those children with both AOM and otorrhoea are 4 and 3, respectively (NICE suggest these may benefit from antibiotics). In other children with AOM, the NNT varies between 8 and 20 pending the measured outcome (NICE does not advise antibiotics in these cases). In our view, and despite the assessment that all four trials were well conducted, the analysis is weakened by the low number of included RCTs and the methodological differences between studies. It probably should not be used for the basis of any firm conclusion regarding the use of antibiotics. Our assessment would be supported by the broad predictive interval for the random-effects distribution. External bias is potentially a significant factor affecting all four studies. The difficulties relating to diagnosis have already been emphasised. Each of the four RCTs considered here uses slightly different diagnostic protocols (see ) which is likely to contribute to variation in outcome. There are different criteria for inclusion or exclusion based on duration of symptoms. Two of the four studies include imaging as part of their diagnostic criteria. In only two is the possible use of ancillary drugs considered, and just one has included detailed use of these drugs as part of the participant breakdown. This is of importance as there is evidence for symptom improvement using douching, steroids, decongestants, antileukotrienes and antihistamines.[39] In all four studies, there is exclusion of patients based around severity assessment, or in one case positive streptococcal cultures. One of the RCTs has been criticised for its overly strict criteria in which patients with slightly more severe symptoms were excluded, clearly this may have biased this trial against bacterial infections.[11 30] Age range criteria are different for each of the four studies as are either the antibiotics or antibiotic doses used as the treatment option. It is the questionable grounds for external validity, therefore, that makes these four studies a poor source for evidence-based generalisation. Clearly, patient selection methodology has the potential to either favour or disfavour the percentage of those with bacterial causes for acute rhinosinusitis included in each study; the true effect of antibacterials cannot be identified until this source of bias is made consistent between studies.

Table 2. Summary of findings from included studies

Name

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes

Potential bias

Wald 1986

Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score and sinus radiographs. Symptoms for minimum of 10 days. Exclusion of patients with

216 years seen at primary or secondary services. Attrition to 93 patients out of 136. Amoxicillin (30); amoxicillin-

Intervention period10 days. Amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/d in divided doses in both amoxicillin and in

Outcomes assessed at 3 and 10 days. Children receiving either antibiotic statistically more likely to be cured at 3 and 10 days (p<0.01 and <0.05 respectively). Adverse effects:

Randomisation method not described. No intention to treat method. No detail regarding possible use of ancillary drugs. Use of sinus radiographs decreases external

6/11

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

+ve grp A streptococci swabs. Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score. Symptoms for minimum of 10 Garbutt days. Exclusion 2001 of patients with fulminant/severe disease or concurrent illness; symptoms >28 days Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score and sinus ultrasonography. Exclusion of patients with concurrent illness or treatment; symptoms >3 weeks Randomised controlled trial, double blind. Clinical severity score. Exclusion of patients with symptoms >30 days; concurrent illness or treatment; acute sinusitis complications.

clavulonate (28); placebo (35). 118 years seen at primary care centres. 161 included: amoxicillin (58); amoxicillinclavulonate (48); placebo (55). 410 years seen at primary health centre. Attrition to 72 patients out of 82 enrolled. Cefuroxime (35); placebo (37). 110 years seen at primary and secondary centres. 56 patients enrolled; amoxicillinclavulonate (28), placebo (28).

amoxicillinclavulonate groups.

diarrhoea (5 antibiotic; validity.Cochrane 1 placebo); rash (1 Collaboration 6 antibiotic; 1 placebo). domain tool: Low risk of bias. Outcomes assessed at 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28 and 60 days. No difference in patient outcomes between groups. Symptoms improved over time for all groups with no significant difference (p=0.80). Adverse effects gastrointestinal or rash (antibiotic group 16, placebo 5).

Intervention period14 days. Amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/d in divided doses. Amoxicillin, in amoxicillinclavulonate, 45 mg/kg/d in divided doses.

Possible bias with exclusion of patients with more severe disease.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bias.

Kristo 2005

Primary outcome assessed at 14 days. No significant Intervention difference noted period10 between 2 groups. days. 'Cure' in antibiotic Cefuroxime group 63% and 125 mg twice placebo group 57%. daily. Adverse effects: diarrhoea (1 antibiotic; 2 placebo).

No intention to treat model. Use of sinus ultrasonography decreases external validity.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bias.

Wald 2009

Intervention period14 days (?). Amoxicillin, in amoxicillin clavulonate, 90 mg/kg/d in divided doses.

Primary outcome assessed at 14 days. Significant more 'cures' in the antibiotic group (14) than placebo group (4) (p=0.01). Adverse effects mostly diarrhoea (12 antibiotic; 4 placebo).

No detail regarding possible use of ancillary drugs. Intended sample size not attained.Cochrane Collaboration 6 domain tool: Low risk of bia

Conclusions

At the pragmatic level, it would be useful to know whether the prescription of antibiotics as routine treatment for acute rhinosinusitis in children, irrespective of uncertainties as to the cause of sinus inflammation, is warranted in terms of safety and effectiveness. Our conclusion from this review would be that the evidence

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 7/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

to support the routine use of antibiotics here remains unclear despite the positive findings of the statistical analysis. The evidence base is clearly inadequate and may be placed in the context of the larger systematic review reported for adult patients which does suggest some small benefit from the use of antibiotics. Future RCTs on this subject are faced with the difficulty of bringing further uniformity and accuracy to the application of diagnosis; this is a significant challenge as the introduction of any radiological or other diagnostic test is likely to detract from utility in primary care, yet diagnostic criteria that are too unrestrictive may lack the power of consistency between studies. Studies with more inclusive criteria are less likely to demonstrate antibiotic efficacy than those that favour the capture of participants with more severe symptoms. The authors would support current UK guidelines that promote a conservative approach to the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis in children with antibiotic prescribing only in selective cases.

Sidebar 1

What is Already Known on This Topic

Acute rhinosinusitis is one of the leading reasons for antibiotic use in children. UK guidelines recommend a conservative approach and avoidance of antibiotics where possible. Recent systematic reviews suggest a marginal advantage for antibiotic use over placebo for treating acute rhinosinusitis in adults.

Sidebar 2

What This Study Adds

Meta-analysis of four trials studying acute rhinosinusitis in children demonstrated great uncertainty in any benefit provided by antibiotics. The role of antibiotics in acute rhinosinusitis in children is not clear; current UK guidelines remain applicable.

References

1. Subcommittee on management of sinusitis. Clinical practice guideline: management of sinusitis. Pediatrics 2001;108:798808. 2. Low DE, Desrosiers M, McSherry J, et al. A practical guide for the diagnosis and treatment of acute sinusitis. CMAJ 1997;156:S114. 3. Giebink S. Childhood sinusitis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. PediatrInfect Dis J 1994;13:S558. 4. Incaudo GA, Wooding LA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute and subacute sinusitis in children and adults. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 1998;16:157204. 5. Kaliner MA, Osguthorpe JD, Fireman P, et al. Sinusitis: bench to bedside. Current findings, future directions. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;116:S120. 6. NICE. Respiratory tract infectionsantibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. Clinical Guideline 69, 2008. 7. Wald ER, Guerra N, Byers C. Upper respiratory tract infections in young children: duration of and frequency of complications. Pediatrics 1991;87:12933. 8. DeMuri GP, Wald ER. Complications of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. PediatrInfect Dis J

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 8/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

2011;30:7012. 9. Kogutt MS, Swischuk LE. Diagnosis of sinusitis in infants and children. Pediatrics 1973;52:1214. 10. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. Acute sinusitis in children: current treatment strategies. Paediatr Drugs 2003;5:7180. 11. Harris SJ, Wald ER, Senior BA, et al. The sinusitis debate. Pediatrics 2002;109:1667. 12. Lacroix JS, Ricchetti A, Lew D, et al. Symptoms and clinical and radiological signs predicting the presence of pathogenic bacteria in acute rhinosinusitis. ActaOtolaryngol 2002;122:1926. 13. Fireman P. Diagnosis of sinusitis in children: emphasis on the history and physical examination. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992;90:4336. 14. McQuillan L, Crane LA, Kempe A. Diagnosis and management of acute sinusitis by pediatricians. Pediatrics 2009;123:e1938. 15. McCaig F, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA 2002;287:3096102. 16. Wasserfallen JB, Livio F, Zanetti G. Acute rhinosinusitis: a pharmacoeconomic review of antibacterial use. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22:82937. 17. Shapiro DJ, Gonzales R, Cabana MD, et al. National trends in visit rates and antibiotic prescribing for children with acute sinusitis. Pediatrics 2011;127:2834. 18. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:e72e112. 19. Ashworth M, Charlton J, Ballard K, et al. Variations in antibiotic prescribing and consultation rates for acute respiratory infection in UK general practices 19952000. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:6038. 20. NHS Evidence CKS Sinusitis March 2009. http//www.cks.nhs.uk/sinusitis (accessed 18 Jul 2012). 21. Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinol Suppl 2007;20:1136. 22. Morris P, Leach A. Antibiotics for persistent nasal discharge (rhinosinusitis) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD001094. 23. Falagas ME, Giannopoulou KP, Vardakas Z, et al. Comparison of antibiotics with placebo for treatment of acute sinusitis: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:54352. 24. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenko OV, Kovanen N, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis (review). The Cochrane Library 2009;(4):193. 25. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 26. Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. 2007. 27. Garbutt JM, Goldstein M, Gellman E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for children with clinically diagnosed acute sinusitis. Pediatrics 2001;107:61925. 28. Kristo A, Uhari M, Luotonen J, et al. Cefuroxime axetil versus placebo for children with acute respiratory infection and imaging evidence of sinusitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Paediatr

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 9/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

2005;94:120813. 29. Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillinclavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Pediatrics 1986;77:795800. 30. Wald ER, Nash D, Eickhoff J. Effectiveness of amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium in the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics 2009;124:915. 31. Meltzer EO, Bachert C. Treating acute rhinosinusitis: comparing efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray, amoxicillin, and placebo. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2005;116:128995. 32. De Sutter A, De Meyere MJ, Christiaens TC, et al. Does amoxicillin improve outcomes in patients with purulent rhinorrhea? A pragmatic randomized double-blind controlled trial in family practice. J Fam Pract 2002;51:31723. 33. De Sutter A, Lemiengre M, Van Maele G, et al. Predicting prognosis and effect of antibiotic treatment in rhinosinusitis. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:48693. 34. Williamson IG, Rumsby K, Benge S, et al. Antibiotics and topical nasal steroid for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;298:248796. 35. Lindbaek M, Hjortdahl P, Johnsen UL. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of penicillin v and amoxycillin in treatment of acute sinus infections in adults. BMJ 1996;313:3259. 36. Jeppesen F, Illum P. Pivampicillin ( pondocillin) in the treatment of maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol 1972;74:37582. 37. Haye R, Lingaas E, Hivik HO, et al. Azithromycin versus placebo in acute infectious rhinitis with clinical symptoms but without radiological signs of maxillary sinusitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1998;17:30912. 38. Otten FW. Conservative treatment of chronic maxillary sinusitis in children. Long-term follow-up. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 1997;51:1735. 39. Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;38:26075. Contributors MJC is the principle author, undertook the quantitative analysis and contributed to all sections of the review. SK assisted with the literature search, assessment of studies for inclusion and planning of the review. SS undertook an independent review both of the literature search and of the assessment of included studies for internal and external bias.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Prisma

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print 10/11

23/04/13

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

We have referred to the PRISMA statement for the reporting of this systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(4):299-303. 2013 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780906_print

11/11

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Empirical First Line AntibioticsDocument1 pageEmpirical First Line Antibioticsdiati zahrainiPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Saudi Commission Manual Classifies Health PractitionersDocument38 pagesSaudi Commission Manual Classifies Health Practitionerstoplexil100% (1)

- Blood Cells and Its Types With FunctionsDocument5 pagesBlood Cells and Its Types With Functionskaleb16_2Pas encore d'évaluation

- BANERJEE P Materia Medica of Indian DrugsDocument133 pagesBANERJEE P Materia Medica of Indian DrugsRipudaman Mahajan89% (9)

- DiarrheaDocument24 pagesDiarrheaash ashPas encore d'évaluation

- Medtronik Qlty ManualDocument40 pagesMedtronik Qlty ManualtimkoidPas encore d'évaluation

- Impetigo: A Bacterial Skin InfectionDocument13 pagesImpetigo: A Bacterial Skin InfectionTasya SyafhiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergency Preparedness Concepts Test BankDocument13 pagesEmergency Preparedness Concepts Test BankTyson Easo JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison of Common Football Helmets in Preventing Concussion, Hemorrhage and Skull Fractures PDFDocument1 pageComparison of Common Football Helmets in Preventing Concussion, Hemorrhage and Skull Fractures PDFAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Guías Reducen Utilización de Recursos en Bronquiolitis - Pediatrics-2014-Mittal-peds.2013-2881 PDFDocument10 pagesGuías Reducen Utilización de Recursos en Bronquiolitis - Pediatrics-2014-Mittal-peds.2013-2881 PDFAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Neurobehavioural Effects of Developmental Toxicity - Chemicals - LANCET PDFDocument9 pagesNeurobehavioural Effects of Developmental Toxicity - Chemicals - LANCET PDFAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Alteran Las Farmacéuticas El Diagnóstico de Las Enfermedades - Journal - Pmed.1001500Document12 pagesAlteran Las Farmacéuticas El Diagnóstico de Las Enfermedades - Journal - Pmed.1001500Alcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Polio Risk Assessment Transmission in IsraelDocument50 pagesPolio Risk Assessment Transmission in IsraelAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis BMJ 2013 PDFDocument7 pagesAdolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis BMJ 2013 PDFAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- AACAP 98 Children and Gangs PDFDocument3 pagesAACAP 98 Children and Gangs PDFAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- TC y Riesgo de Cáncer en La Niñez y Adolescencia - BMJDocument18 pagesTC y Riesgo de Cáncer en La Niñez y Adolescencia - BMJAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- Unknown Toxin May Be Cause of Pertussis CoughDocument2 pagesUnknown Toxin May Be Cause of Pertussis CoughAlcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- AAP - Rinosinusitis - Información para Padres - AAP News-2013-Starr-4Document3 pagesAAP - Rinosinusitis - Información para Padres - AAP News-2013-Starr-4Alcibíades Batista GonzálezPas encore d'évaluation

- JK SCIENCE: Verrucous Carcinoma of the Mobile TongueDocument3 pagesJK SCIENCE: Verrucous Carcinoma of the Mobile TonguedarsunaddictedPas encore d'évaluation

- Sound Transduction EarDocument7 pagesSound Transduction Earhsc5013100% (1)

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFMohammed FasilPas encore d'évaluation

- Philips Respironics Bipap ST Niv Noninvasive VentilatorDocument2 pagesPhilips Respironics Bipap ST Niv Noninvasive Ventilatorsonia87Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 8 Spelling WordsDocument2 pagesChapter 8 Spelling Wordsapi-3705891Pas encore d'évaluation

- Medicine in Situ Panchen TraditionDocument28 pagesMedicine in Situ Panchen TraditionJigdrel77Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kinesiology Elbow Joint PDFDocument8 pagesKinesiology Elbow Joint PDFRozyPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnostic Imaging Equipment & Consumables Laser PrintersDocument5 pagesDiagnostic Imaging Equipment & Consumables Laser Printersnanu_gomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Don't Steal My Mind!: Extractive Introjection in Supervision and TreatmentDocument2 pagesDon't Steal My Mind!: Extractive Introjection in Supervision and TreatmentMatthiasBeierPas encore d'évaluation

- Wallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy JournalDocument1 pageWallen Et Al-2006-Australian Occupational Therapy Journal胡知行Pas encore d'évaluation

- CCMP 2020 Batch Cardiovascular MCQsDocument2 pagesCCMP 2020 Batch Cardiovascular MCQsharshad patelPas encore d'évaluation

- 950215man 06187Document58 pages950215man 06187Electrònica Mèdica De La LagunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Surgical Treatments For EDDocument31 pagesMedical Surgical Treatments For EDskumar_p7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Document8 pagesDaftar Obat Slow Moving Dan Ed Rawat Inap Maret 2021Vima LadipaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review On Acacia Arabica - An Indian Medicinal Plant: IJPSR (2012), Vol. 3, Issue 07 (Review Article)Document11 pagesA Review On Acacia Arabica - An Indian Medicinal Plant: IJPSR (2012), Vol. 3, Issue 07 (Review Article)amit chavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre Employment Occupational Health FormDocument7 pagesPre Employment Occupational Health Formlinks2309Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal InvaginasiDocument3 pagesJurnal InvaginasiAbdurrohman IzzuddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Elgabri v. Lekas, M.D., 1st Cir. (1992)Document21 pagesElgabri v. Lekas, M.D., 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Doctors by SpecialtyDocument6 pagesList of Doctors by Specialtykaushal shahPas encore d'évaluation

- Essential and Non-Essential Fatty Acids PDFDocument4 pagesEssential and Non-Essential Fatty Acids PDFBj Delacruz100% (2)

- History of Medicine in India from Ancient Times to Ayurvedic Golden AgeDocument6 pagesHistory of Medicine in India from Ancient Times to Ayurvedic Golden AgeGhulam AbbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Elphos Erald: Second Shot: Hillary Clinton Running Again For PresidentDocument10 pagesElphos Erald: Second Shot: Hillary Clinton Running Again For PresidentThe Delphos HeraldPas encore d'évaluation