Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Unconventional Zones of Nostalgia: Junkies, Zombies and Broken Homes From Cabo Verde To Fontainhas

Transféré par

Robbie BruensTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Unconventional Zones of Nostalgia: Junkies, Zombies and Broken Homes From Cabo Verde To Fontainhas

Transféré par

Robbie BruensDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Robbie Bruens / May 3, 2011 Brizuela / Film 151

Unconventional Zones of Nostalgia:

Junkies, Zombies and Broken Homes from Cabo Verde to Fontainhas

Pedro Costas movies explore the concept of habitation, not just of spaces but also of bodies. He examines bodies that lack the interiority audiences are accustomed to identifying in film and he complicates the nostalgia often associated with the idea of home. Costas problematization of the habitation of a space both in Lisbon and in Cabo Verde runs in parallel with how he challenges interiority through a questioning of who really inhabits the bodies of individuals. Throughout his movies, Pedro Costa contaminates the individual and home we recognize from more conventional narratives with fractured spirits, ghosts and zombies of the supernatural world leading us to question how we view intermingled feelings of nostalgia, identity and memory. In the short film Tarrafal, Pedro Costa makes literal the common metaphors of habitation present throughout his earlier movies. Thus it can serve as a useful point of entry for analyzing how these metaphors inhabit the core of his work. Two conversations in the film are fairly explicit in discussing habitation. The first conversation starts the movie and it concerns the habitation of a place from the past. The second conversation appears near the end and it concerns a man who may be a ghost or zombie. Both of these conversations take place inside the same house and they are separated in the movies brief running time by exterior scenes that present

an oblique visualization of the supernatural contamination that underlies both conversations. At the beginning of Tarrafal, Lucinda Tavares and Jose Alberto Silva sit inside a house discussing the home where Lucinda once lived. Jose asks Lucinda a series of questions about this home. Jose questions Lucinda in a way that makes its clear that he remains unfamiliar with the space but curious about what it would be like to go back there. Lucinda demurs, explaining that no one lives in that place anymore and that the home lacks basic amenities. Jose seems to reach for any potential nostalgia that Lucinda may possess for a place she lived in long ago. Lucinda responds unromantically. She dismisses the home as a place that no longer exists in a state she would like to inhabit. Jose looks for identity in this forgotten home, but Lucinda refuses to let her memory give Jose a false hope of finding identity. As the short film proceeds, Costa uses exterior spaces to elaborate on the concepts of space habitation he set forth in the beginning. Jose marches around with a letter that is shown in full at the end of the film to be forcing Jose to return to Cabo Verde. Because he barely knows this home, he is curious to find out about it from Lucinda. The authors of the deportation letter do not appear in the movie. They are ghosts to the audience. Lucinda later refers to bloodsuckers delivering letters in secret. Through the anonymous forces behind the deportation, the bloodsuckers, Costa contaminates the nostalgia of home with supernatural spirits. Before the end of Tarrafal, Ventura (who appeared in an earlier Costa film) tells a story in the same house that Lucinda and Jose sat in earlier. The story recounts Venturas experience in a restaurant where [he] knew nobody and

nobody knew [him]. Ventura repeats this line, signifying his uncertain identity. While the story could be interpreted simply as being about a poor man who goes to a nice restaurant, skips out without paying the check and suffers punishment as a result, the otherworldly ambiguity that Ventura imbues in its telling forces the audience to question Venturas identity and place in the story. It remains unclear who exactly inhabits Venturas body. When the man listening to Venturas story asks if Ventura was killed before being dumped by the railroad tracks and Ventura answers inconclusively, Costa asks the question of whether Ventura is a man, a ghost or a zombie. If Ventura is a ghost or a zombie, it remains unclear how he became one. Costa seems interested in inhabiting the bodies in his films with a supernatural ambiguity because it allows him to breakdown a conventional cinematic interiority. By making movies about lost people living on the margins of society, Costa invites questions about agency and motivation that subvert the rationalist singular individual mode of understanding behavior. Venturas story fits this style because we are never sure about his motivations or how he relates to others in the story. Ventura is a ghostly floating subject that insists on ambiguity when it comes to the habitation of his body. Casa de Lava begins by disturbing the habitation of a body almost immediately. An industrial accident injures Leo and he is suspended in a comatose state between life and death. The mystery of what really inhabits Leos body persists throughout the movie. But Costa organizes his narrative around a moment early in the film. A comatose Leo receives an anonymous letter asking for his

return to his homeland of Cabo Verde. Thus the disturbance of habitation extends to a place as well as a body. While still unconscious in a hospital bed, Leo is sent back to Cabo Verde as the letter requested. The rest of the movie unfolds on Cabo Verde, as Leo becomes a sort of zombie. In this way, Costa explores habitation of places and bodies in parallel. Costa embeds several ambiguities of habitation in the moment when the letter is received. Like the conversation between Lucinda and Jose in Tarrafal, in Casa de Lava a former resident of Cabo Verde is asked to engage in a nostalgia play about remembering and returning to home. But neither former resident is willing to engage. Lucinda complicates the nostalgia actively while Leo does it passively by not being able to respond at all. Costa demonstrates the sham of attempting to return home to a place that no longer exists except in the fog of memory. In each movie, the forces that push for that false return to Cabo Verde share in common a faceless anonymity only manifested physically in the form of letters. These are the ghosts that contaminate identity through body and place. In Tarrafal, Costa uses a letter from a faceless bureaucracy of ghosts forcing Jose to return a place he barely knows. In Casa De Lava, Costa uses a letter authored by the ghosts of anonymity to drive Leos return to Cabo Verde. While an anonymous letter helps catalyze the narrative in Casa de Lava, it is hardly the only faceless and impersonal active force in the movie. The industrial accident that opens the film, the medical establishment that takes over Leos life and ships him back to Cabo Verde where it continues to drug him, and the economic factors that lead Leos family in Cabo Verde to plan to immigrate to Lisbon all form

a backdrop of institutional pressures that shape the habitation of bodies and spaces. To some extent, Costa complicates these spaces with the supernatural in order to represent how these ghostly institutions affect the people in his movies. Colossal Youth howls with haunted habitation both with its population of floating, supernatural beings and the stark architecture of its markedly empty locations. The ability to read Colossal Youth in this way hinges largely on Ventura who will later appear in Tarrafal. Like a zombie, Ventura moves through the film with a halting stagger. The habits of the undead inhabit his body in addition to the gait, he repeats himself endlessly, plays a number of aimless card games, and keeps an alienating social distance from many others in the movie. He longs to be reunited with the ghosts of his past, even as the present bleeds into his imagined history. The main text that Ventura repeats comes from a love letter in Casa de Lava. In this way, Costa contaminates his most recent feature with a ghost from an earlier work. Costa juxtaposes Venturas spirituality with highly modern constructed spaces in Lisbon. In one shot, Venturas dark visage appears to divide in half the sharp angular structure of the sheer white buildings that appear in the movie. Ventura looks like an unnatural visitor to this conspicuously artificial landscape. Vanda! he calls out repeatedly, as if exorcising a ghost from old Lisbon for company in this new and unfamiliar place. Vanda represents an intertextual link to an earlier Costa feature that surveyed the slums of old Lisbon. Costa interposes Ventura between the built environments of old and new Lisbon providing one of the clearest examples of how he parallels the distressed habitation of bodies.

Two moments in Colossal Youth particularly highlight Costas interrogation of the old and new city. They both arrive relatively early in the film and seem to echo each other for special emphasis. They meld the contamination of bodies and spaces so seamlessly it is difficult to separate them for analysis. In these two moments, the forms of habitation do not merely parallel each other but actually fully intersect and intermingle. They involve the habitation of two different spaces that each possess a different intonation of home for Ventura. The first moment occurs in a sequence that follows Ventura from where he lives in the slums of old Lisbon to the new Lisbon with the aforementioned unfamiliar built environment. As the slums disappear, Ventura is visiting what could be his new home. The apartment is full of light, says the locksmith who acts as the administrative agent showing the new apartment. The bright whiteness stands in contrast to the gray gloom of Venturas current residence that appeared in the scenes immediately preceding this sequence. After walking up to the apartment, Ventura is too weak to actually open the apartments front door. My heads spinning. Im aching all over, he explains to the locksmith who opens the door for him. The next two shots contain the moment under analysis. After entering the apartment, the aching Ventura leans against a wall of the apartment. His head rests on its surface as he looks up in bewilderment. During this close up on Ventura, the locksmiths voice interrupts with a mechanized list: Temple, shack, house God. Then a slightly wider shot shows Ventura leaving the wall and the locksmith using his shirtsleeve and fist to brush off the surface where Ventura had rested his head.

The light and the height of this unfamiliar building inhabit Ventura with a supernatural discomfort. For a few moments, he cannot open a door or even stand up straight. Overwhelmed, he must lean on the wall of this bright, anti-septic environment that he is considering as a possible home. This bourgeois ideal house, the house God that serves as both a temple and a shack, disturbs Venturas identity as well as its own in this moment of rupture. But then the locksmith restores dignity by washing away the contamination Ventura left on the wall. The locksmith cleans the wall in a kind of absurd flourish. It is as if this house is too pure to be inhabited by anyone. Its virginal sterility must be maintained at all costs. Only spirits without the filth of a body may live there. Zombies need not apply. And Ventura must maintain his own integrity as a zombie. He must remain in the slums. The second moment comes roughly twenty minutes later, when Ventura once again enters a rather pristine building of new Lisbon. This time, it is a museum run by a foundation that will later fund Pedro Costas Tarrafal. The sequence opens with a lingering shot of a painting followed by a shot of Ventura once again leaning against a wall. This wide shot shows him bracketed by two paintings, looking out of place. And yet Ventura seems more comfortable here because he knows this place. He helped build it when he worked as a laborer. A museum guard enters the shot and whispers something to Ventura. The audience cannot hear what is said, but Ventura responds by leaving the wall behind and walking elsewhere. Subsequently, the guard pulls a handkerchief out of his pocket and bends down to wash off the spot where the zombie just stood moments ago. Once he has gently dusted off the ground in two strokes with the white piece of cloth, he slowly rises and walks out of

the shot in the opposite direction. Later in the scene, the guard holds out his hand to Ventura and guides him out of the museum altogether after Ventura sits on some furniture that may be part of an exhibit. While recalling that Venturas ill-fitting habitation of the environment brings to mind the story he will later tell in Tarrafal about the restaurant where he knew no one and no one knew [him], the way this moment mirrors Venturas earlier appearance at the apartment showing goes beyond reminiscence. The moment is entirely an echo of Venturas encounter with the locksmith in the sterile white house God. Previously, Ventura had leaned on a wall for support after being overwhelmed by the house so bright and alien to his experience in the slums. This time, he leans back on the wall comfortably in this darker and more cavernous setting that he feels connected to by his role in constructing the place. After feeling separation from the house God by its seemingly foreign identity, he feels joined to the museum by memory of his laboring past. But Costa unites the scenes thematically by showing how a backdrop of institutional authority mediates both kinds of habitation. He represents this mediation in the brief dusting motion of both the locksmith and the guard, a careful cleaning of the small space contaminated by the zombie from the slums. Looking at these two scenes in comparison to one another at a higher order of magnitude, one can understand a further point Costa makes about the habitation of bodies by ghosts of nature. If we ignore the difference in settings, these two scenes are nearly identical. Ventura behaves in the same repetitive fashion with the automatic habits of a zombie regardless of how he feels about the world around him.

He leans on the wall, he walks when spoken to, and in the first case he leaves after being dissatisfied while in the second case he leaves after dissatifisying another. Even more importantly, the locksmith and the guard behave in the exact same way. They are also zombies, following Ventura, cleaning up after him, and driving him out of their buildings with the force of institutional bureaucracy. But if they are bodies inhabited by zombie spirits, they may not be aware of it. But they can both tell that Ventura is a zombie, and deal with him accordingly. In Costas work, everyone is a kind of zombie. At the very least, they are inhabited by multiple spirits that often drive them through the motions of life, controlled by homes that complicate their respective identities, or attempting to control others homes and memories. Costa understands these zombies as people caught up in the conventions, traditions and inertia of human activity. He views them through a lens of habitation that contains two loci: the body and the home. Between these two spaces spirits fly, the predators of faceless institutions feeding on the prey of ghosts stranded far from home.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- An Exemplary Western by André BazinDocument4 pagesAn Exemplary Western by André BazinRobbie BruensPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Mise en Scene? by AstrucDocument3 pagesWhat Is Mise en Scene? by AstrucRobbie BruensPas encore d'évaluation

- Macaulay Glorious Revolution EssayDocument2 pagesMacaulay Glorious Revolution EssayRobbie BruensPas encore d'évaluation

- History of England by Lord MacaulayDocument38 pagesHistory of England by Lord MacaulayRobbie BruensPas encore d'évaluation

- Selected Poems by Louis ZukofskyDocument8 pagesSelected Poems by Louis ZukofskyRobbie Bruens100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- FMCG Ebook 2023Document24 pagesFMCG Ebook 2023Ardian Prawira YudhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Intermediate 2. FinalDocument3 pagesTest Intermediate 2. FinalLUIS MANUEL GONZALES DELGADOPas encore d'évaluation

- Karya Ilmiah Psikologis Sastra - XI MIPA 1Document10 pagesKarya Ilmiah Psikologis Sastra - XI MIPA 1rayPas encore d'évaluation

- PE 10 Q 1 MODULE 1 (Dagyaw) 2Document31 pagesPE 10 Q 1 MODULE 1 (Dagyaw) 2utePas encore d'évaluation

- AS4000 Installation Manual 925600Document142 pagesAS4000 Installation Manual 925600Brandon100% (1)

- 12 09 04Document16 pages12 09 04Sarma SalagramaPas encore d'évaluation

- MBN Lec5 Part1-WlanDocument74 pagesMBN Lec5 Part1-WlanPrince AbidPas encore d'évaluation

- Model S Owners Manual North America en Us PDFDocument233 pagesModel S Owners Manual North America en Us PDFJason LiPas encore d'évaluation

- Astron Power SupplyDocument8 pagesAstron Power Supplydmechanic8075Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gates of MadnessDocument75 pagesGates of MadnessJasmine Crystal ChopykPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 Kung Fu Panda - ComparativesDocument2 pages21 Kung Fu Panda - ComparativesOana MirceaPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 06 11 023 S ks2 PDFDocument1 page07 06 11 023 S ks2 PDFSharmila ShankarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson IV. Music Presentation By: Shiela Mae F. Cabusao Anne Dominique M. Ventura Francis Michael C. Tejero Amparo C. Uy What Is Music?Document2 pagesLesson IV. Music Presentation By: Shiela Mae F. Cabusao Anne Dominique M. Ventura Francis Michael C. Tejero Amparo C. Uy What Is Music?Romeo BalingaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading-Grade 5-A Package For Mrs JewlsDocument33 pagesReading-Grade 5-A Package For Mrs JewlsSofi NassarPas encore d'évaluation

- Acknowledgment For Request For New PAN Card or - and Changes or Correction in PAN Data (881030205408706)Document1 pageAcknowledgment For Request For New PAN Card or - and Changes or Correction in PAN Data (881030205408706)kapilchandanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Four Quarters Magazine 2013Document85 pagesThe Four Quarters Magazine 2013Vasundhara Chandra100% (1)

- Self Myofascial ReleaseDocument2 pagesSelf Myofascial Releasesonopuntura100% (2)

- Rock Project RubricDocument4 pagesRock Project Rubricapi-281980239Pas encore d'évaluation

- Seac Sub AssoDocument6 pagesSeac Sub Assobeard007Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biography Poem Just BecauseDocument6 pagesBiography Poem Just BecauseMy Linh PhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pet Reading Practice 3Document10 pagesPet Reading Practice 3Jugador FelizPas encore d'évaluation

- Purple Parrot Menu at AtlantisDocument8 pagesPurple Parrot Menu at AtlantisClarita BernardinoPas encore d'évaluation

- STrORrLUQmi7DzX7u1Hr Orchestration EssentialsDocument9 pagesSTrORrLUQmi7DzX7u1Hr Orchestration EssentialsClément PirauxPas encore d'évaluation

- Process Flow ChartDocument3 pagesProcess Flow ChartJulie Anne Baldoza LaurelPas encore d'évaluation

- iconBiT XDS1003DT2 - UM - EN - RU PDFDocument66 pagesiconBiT XDS1003DT2 - UM - EN - RU PDFVasia DeminPas encore d'évaluation

- Incidentrequest Closed Monthly MayDocument345 pagesIncidentrequest Closed Monthly Mayأحمد أبوعرفهPas encore d'évaluation

- Planificare KID'S BOX 2022-2023Document4 pagesPlanificare KID'S BOX 2022-2023SANTA ANAMARIA-SUSANAPas encore d'évaluation

- Learn How To MassageDocument21 pagesLearn How To MassageEskay100% (29)

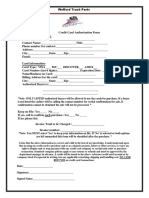

- Credit Card Authorization Form WoffordDocument1 pageCredit Card Authorization Form WoffordRaúl Enmanuel Capellan PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindi Book Bhavan Bhaskar Vastu ShastraDocument80 pagesHindi Book Bhavan Bhaskar Vastu ShastraCentre for Traditional Education100% (1)