Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

AlexanderHeracles Statue

Transféré par

mariafrankieDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AlexanderHeracles Statue

Transféré par

mariafrankieDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Alexander: Heracles: A Preliminary Note Author(s): Erik Sjqvist Reviewed work(s): Source: Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts,

Vol. 51, No. 284 (Jun., 1953), pp. 30-33 Published by: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4171154 . Accessed: 13/07/2012 03:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts.

http://www.jstor.org

LI, 30

BULLETIN OF THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

In 1939,AhmedYoussef,who had been lent to the Expeditionby the CairoMuseum,completed the difficulttask of replacing the thin gold sheets copyof the box for andfaienceinlayson a modern the curtainsof the bed canopy. The inscriptions Sneferu,the give the titles of the queen'shusband, firstkingof Dynasty IV. The boxhas so far only been publishedin an articleby Reisnerin the Illustrated LondonNews, November 18, 1939, pp. 757-758. At the sametime, AhmedYoussefprepared a reproduction of the box for the Boston Museum (Fig. 2; Acc. No. 39.746). Unfortunately the wood was affected by the climatic changefromEgypt to Americaand had to be removed from exhibitionin the Museum after a shorttime and allowedto standfor a considerable periodto determinewhetherfurtherstresswould be exertedon the plasteredand gilded surfaces. Mr. Young has now treated these again and the box has recently been returned to exhibition. of the footboardof Togetherwith the decoration the bed, of which a reproductionis exhibited of the nearby, this box gives a vivid impression skill of the Old Kingdomdesigner. Even more elaborate are the hawks, feather patterns, and fromthe secondarmchair(Fig. 7) and the flowers inlaid designson the lid of the chest which contained the braceletbox (Fig. 8). In the summer of 1952I was able to examinethis materialagain in the CairoMuseumwith AhmedYoussefand to checkthe inlay patternsand gold sheetswith my restored drawings. It was proposedthen that AhmedYoussefshouldcompletethe workof restorationand it is hopedthat he may soon be able to turnhis ingenuityto the chairandchest, which and showypiecesof are the most richlydecorated all the furniture. A glance at the photographof the tomb of Hetep-hereswhen it was first opened (Fig. 3) shows clearlyhow hopelesslookingwas the condition of the decayedmaterial,with the woodinside the gold casingsof the furniture eithershrivelled to a fractionof its originalbulk or else deof cigarash. All the teriorated to the consistency more amazingwas Reisner'sachievementin recovering the original appearance of virtually the faevery one of the objects. In comparison, mous equipmentof the tomb of Tut-ankh-amen wasin soundcondition,as wellas beingsome 1300 yearsmorerecent(1353B.C. as against2650 B.C. has furniture for Hetep-heres). The Hetep-heres less attentionthan that of attractedconsiderably Tut-ankh-amen, partly becausethere werefewer piecesand partlybecauseit belongedto a time of simpler living conditions.However, it is fully of the first great periodof Egyprepresentative tian achievement. The fine proportions and reflectthe same spirit boldlydesigneddecoration of Dynasty IV, the as the greatportraitsculpture wonderful wall reliefs,and the paintingas exemplifiedby the famousMedumGeese.

SMITH WILLIAM STEVENSON

7

1-j

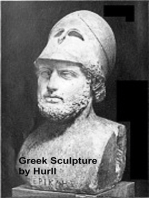

Fig. 1. Headof Alexander

Otis NorcrossFund

Alexander - Heracles: A Preliminary Note marblehead which is here presented'is not a newcomerto the Museum(Fig. 1). It paid its first visit to Boston as early as in the summerof 1910, then on loan from Mrs. John Newbold Hazard of Peacedale,L. I., and after variousvicissitudeswas again depositedhere by Mrs. Hazard'sdaughter,Mrs. D. H. Reese, from whomit has now been recentlyacquired. It was bought in Sparta in 1908 and went through a preliminarycleaning process in the British Museum in the same year before being W. Romaine broughtby its firstowner,Professor Newbold, to Philadelphia. The importanceof the head, clearlyenvisagedby its learnedowner, was soonconfirmed by specialistsin the field. In it2 for WilliamN. Bates published 1909Professor the first time. It was brieflypresentedby Dr. L. D. Caskeyin this Bulletinin the followingyear and was furtherdiscussedby two other scholars in subsequent years.:3 of the headthereis little to To theirdescription may add, and a summaryof earlierobservations sufficeas a presentation. It is somewhatunder life-sizeandmadeof Pentelicmarblewhichon the

I Head of Alexander; 52.1471: Otis Norcross Fund. W. N. Bates, "A head of Heracles in the style of Scopas," AJA, XIII, 1909, pp. 151-157. 3 L. D. Caskey, "A Marble Head of Herakles," Bullefin M. F. A., Vol. VIII, 1910, pp. 26-27: W. W. Hyde, "The Head of a Youthful Heracles from Sparta," AJA, XVIII, 1914, pp. 462-478; id. in Olympic Victor

2

THE

Athlctic Art,Wash.1921,pp. 305-320;R. G. Kent, andGreek Monuments fromSparta,"Procecd. of theNumism.and AntiHercules "The Baffled in a Soc. of Philadelphia, vol. 29, pp. 85-104 (later produced quarian reprint,1923). corrected

OF FINE ARTS OF THE MUSEUM BULLETIN

LI, 31

Sicyon, 330 B.C. of Alexander, Fig. 2. Teiradrachm

-U

Fig. 4. Head of Alexander Otis NorcrossFund

Fig. 3. Headof Alexander Athens, National Museum

right side has taken on a mottled golden brownish patina entirely lacking on the left. The face is remarkably well preserved except for the tip of the nose. The delicate finish of the surface is intact on the right half and only slightly weathered on the left side, which evidently was exposed for some time to the corroding activities of air, wind, and water. The neck and the back of the head with the ears are missing, and the breaks likewise show traces of weathering. The youthful head wears the lion helmet, the traditional equipment of Heracles. The helmet is drawn down rather far, so that muzzle and teeth of the beast overshadow the forehead. This adds to the lively play of light and shadow which is a

of the head, and dramatizes main characteristic of the young face. The intensity the expression in the eyes whichatis concentrated of expression tract the onlookerwith a magneticforce. Their vigorousand sensitivemodellinghas given riseto as to the directionof theirpenetrating speculation gaze. They have been variously described as lookingupward,to the right, or to the left. As a matter of fact, a close examinationreveals that faint tracesexist at least on the left eye of a tiny incisionwhichseemsto markthe outeredgeof the pupil. It lies, however, very near the center,4 and cannotguideus with certaintyin any specific direction. The heavy, slightly fleshy eyebrows give, in any event, the impressionof an upward gaze. glanceratherthan a straightforward This is not the only point of discussionamong those who have earliertreated the head. Bates attributesit to Scopasor his circle,Caskeypoints out Praxiteleanfeaturesin the lowerpart of the head and termsit "an eclecticworkin whichfeaturesfromSkopasand Praxiteleshave beencomeffect." Hyde, binedwith an unusuallysuccessful still consideringit an eclectic work, mentions Lysippus, but denies that Heracles is represented. Instead he suggests that it is an idealized portraitof an unknownvictoriousathlete in the disguiseof Heracles,and bases this assumption on its clearindividualization. Even Caskey

4 1 am

indebted to Miss Hazel Palmer for this observation.

LI, 32

BULLETIN OF THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

a coin in the NewellCollection I herereproduce of the AmericanNumismatic Society (Fig. 2), published by Professor Noe afterthe notes of Mr. Newell.5 Struckin Sicyon in the year 330 B.C., it shows Alexander'slikeness in the traditional Heraclesiconography. It seems to be the king portrayedas Heracles,not Heracles used as an allegoryof this early stage of deificationof the youngruler. The featuresareclearlyindividualized beginningwith the two separate planes in which the forehead is modelled. There is an upperflat sectionand a lowerbulgingone divided by a horizontal groove. The eyebrows arerather heavy and fleshy, the eyes fairly deeplyset, and the nose straight and energetic. These manly, forcefulfeaturescontrastto some extent with the softerandmorerounded formsof mouthand chin. A personalcharacteristic is obviouslyrendered in the strikinglyshortupperlip andthe small,rather sensuousmouth. In later coin issues these features are either over-emphasized or blurred,but these early coins preserve a truer likeness and mark at the same time the first decisive step in the evolutionof an iconography that was totally new to Greekart: that of rendering an imageof a deifiedruler. The final stages of this processended in the famousAlexanderportraitsby Lysippus,so eloquently describedby Plutarchand variousother ancient authors, where we meet him with "his neck bent slightly to the left," "lookingup with his face to the sky," with a "liquidsoftness and in his eyes"and with a "manliness brightness and lion like fiercenessin his countenance." Such were the Lysippanportraitsof Alexanderwhich have come down to posterity in innumerable copiesandin literature, but whichdo not apply to the youngAlexander in 332B.C. whenhe was just 24 yearsold. The official portraitsof that period are,in my opinion,reflected in the coinsof Sicyon and Tarsus. The die-cutterwas not the original portraitist, but the talentedintermediary between a leadingartist of the time and the mass medium of coinage. What did the archetypelook like after which the die-cutterworked? I think a detailedcomparison between the Sicyon coin and our head gives a satisfactoryanswerto the question. All the personalfeatures of the coin image pointed out above are found in the marble head from Sparta, only infinitelyfiner and more plastically rendered:the divided forehead,the heavy eyebrows,the short upperlip, the small mouth, the softly roundedchin. Volume,proportions,and above all the expression are the same. The evidence seems sufficientto identify them as the same person:our head is a portraitof the young Alexanderfrom the time between 332 B.C. and 330 B.C.

5 Numismatic Studies, 6, 1950, p. 12, No. 3.1, P1. 1. The new photograph of the coin we owe to the courtesy of Miss Margaret Thompson of the American Numismatic Society.

had pointedto these featuresand held that it was only the lion-helmetwhich helpedus to identify him with the deifiedhero. Kent goesbackto the Heraclesidea,but connectsit with a localSpartan myth, related by Pausanias(II1,15, 3-5), of the woundedand baffled Heracleswho sneakedaway afterhavingbeenattacked byHippoco6n, a legendary kingof Sparta,and his sons. Pausaniassaw a statue of Heraclesin a sanctuaryclose to the city wall of Sparta,the attitude of whichhe was told had been suggested by this episode. Our head should, accordingto ProfessorKent, be a remnantof that statue. His mainarguments are the expression of the face whichlacks divine serenity- quite appropriately on account of the unusualsituation -and the direction of the eyes, to the quotedauthor,glancingsidewise according towardthe left. In the variety of interpretations and attributions there is a generalconsensuson the great beauty of the head, the finenessof its execution, and its quality of being a Greekworkfrom the fourthcenturyB.C. In this all importantpoint I am in wholeheartedagreementwith the distinguished scholars already mentioned. But theirvery discussion in otherpointsseemsto suggest a new solutionregarding both subject-matter and artist. The pathos,the intensity,andthe individuality of the headstronglysuggesta portraitratherthan an image of an immortal. Its small size speaks decidedly against a cult statue. On the other hand,it wouldbe unparalleled in Greekart of the fourthcenturyto render an athleticvictor,as suggestedby Professor Hyde,in the attireof Heracles. But who could he be? Who among mortals could in the latter part of the fourth centuryaspire to an identificationwith the deified hero? The only possibleanswerseemsto be: Alexander the Great. The deificationof Alexanderduring his own lifetimewas a gradualprocess,which can be followed through our historicalsources. It originated in the old Macedoniankingship, which claimeddescentfromboth Heraclesand Achilles, and gainedmomentumunderthe influenceof the new impressionswhich met Alexanderand his men during the conquest of the East. Soon after having crossedthe Hellespontin 334 B.C. Alexandervisited Ilium, the scene of the great deedsof his ancestorAchilles,and presentedhimself as a reincarnation of the Homerichero. Two years later, after the successfulbattle of Issus, Alexanderbesieged and conqueredthe city of Tyre, valiantlydefendedby its inhabitantsunder the protection of the Phoeniciangod HeraclesMelkhart,the "patronsaint" of the city. After the conquest, in 332 B.C., Alexandertook the placeof the god, and soon after this crucialevent in his early career we meet what I believe to be his imagein Heracles'attire on coins both in the East and in Greeceitself.

OF FINE ARTS OF THE MUSEUM BULLETIN

LI, 33

Thereexistsin the NationalMuseumof Athens a similarAlexanderhead (Fig. 3), of less distinguished quality but still an Attic marble work from the period.6 It is illustratedhere for comboth the faciallikeness parison,and demonstrates in execution. betweenthe two and the difference The Boston head stands out very honorablyin (Fig. 4). the comparison Thereremainsthe questionwhowas the author madein bronze of of the prototype probably in Heraclean the portraitof the young Alexander attire, of which the early coins and the heads in Boston and Athens give so eloquent witness. for obhave to be discarded ScopasandPraxiteles reasons,and the theory of its vious chronological beingan eclecticworkdoesnot answerthe new reHyde's of a royalportrait. Professor quirements pointed clearlytoward Lystylistic comparisons sippus- as, for example, the renderingof the hairof Agiasandof ourhead- and they now obsupportfromexternalevidence. tain considerable Lysippuswas the favoritecourt sculptorof Alexanderthe Great and had already made his first portraitof himwhilethe princewasstill a boy. It seemshardlyplausiblethat he shouldhave been forgotten when there arose the immensely imthe young king of rendering portantcommission Fig. 5. Headof Alexander Otis NorcrossFund being. Stylistic forthe firsttime as a semi-divine analysis and historicalevidencestrengtheneach other reciprocally. What has been considered best contemporary replica so far known, and thus is only the resultof the complexphys- takes an important place not only in the iconeclecticism iognomy of the sitter renderedby a first-rate ography of Alexander the Great, but also in the sculptorin an excellentlikeness,both spiritually studies of the art of Lysippus. and materially(Fig. 5). The Boston head is the ERIKSJdQVIST

6 Brunn,

H. and Arndt, P., Griechischeund Romische Portrdas,Pi. 486.

Princeton University

Accessions,

November 13, 1952 through March 12, 1953

Asiatic Art. Bronze,Chinese. 52.1751. Kuei ("two-handledbowl"), Chou dynasty; 52.1752. Ku (beaker), Chou dynasty............................................ Gift of ArthurWiesenberger. 53.131. Hu (large jar), early Han dynasty........................ Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Bernat. Ceramics, Chinese. 52.1532. Porcelainvase, Kuan type, Ming (?) dynasty; 53.2. Pottery horse, Wei dynasty, sixth century; 53.121. Pottery pillow, unknown ware, Sung dynasty........................ 52.1545. Pottery pillow, Ting ware, Sung dynasty; 52.1546. Marbleizedcoffer, T'ang dynasty; 52.1547. Pottery pillow, Tz'u-chouware, Sung dynasty. Res. 52.107. Small jar, Ching-t-chen ware,Sung dynasty................ 52.1745. Plate decorated in Arita style with Kakiemondesign, eighteenth ........................................... century 53.132-53.133. Pair of small porcelaincups, Yung-ch'eng ........... period Korean. Ceramics, 53.120. Flask-shaped bottle, pottery, third or fourth century .............. Lead,Chinese. 53.32. Figurefor inlay decoration,Han dynasty......................... Paintings, Chinese. Res. 52.108. Pomegranate Branch,by Wan Kuo-cheng,late Ming dynasty.. Paintings,Japanese. 52.1543. Eagles, Crowsand Snowy Treetops, by Kishi Chikudo,nineteenth .Gift century

EdwardS. Morse Fund. Gift of C. AdrianRubel. Gift of Rev. FredericB. Kellogg. Gift of Miss Lucy T. Aldrich. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Bernat. CharlesB. Hoyt Fund. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Bernat. Gift of Miss Pauline Fenno.

of Miss AdelaBarrett,in memoryof Mr. and Mrs. SamuelEddy Barrett. 52.1544. Lotus Bud, by Toyo, AshikagaIdealisticSchool, fifteenthcentury. Gift of Robert T. Paine, Jr.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 1,100 Designs and Motifs from Historic SourcesD'Everand1,100 Designs and Motifs from Historic SourcesÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (7)

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument5 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldKıvanç TatlıtuğPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sarpedon Krater: The Life and Afterlife of a Greek VaseD'EverandThe Sarpedon Krater: The Life and Afterlife of a Greek VasePas encore d'évaluation

- Aphoridte LadderDocument18 pagesAphoridte LadderOrsolya PopovicsPas encore d'évaluation

- Harvard Gods in Color Gallery Guide PDFDocument8 pagesHarvard Gods in Color Gallery Guide PDFsofynew2100% (1)

- Greek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)D'EverandGreek Sculpture: A Collection of 16 Pictures of Greek Marbles (Illustrated)Pas encore d'évaluation

- OrnamentDocument296 pagesOrnamentdubiluj100% (12)

- Social Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art: Family Tree: Stacked Ancestors, Y-Posts & Heavenly LaddersD'EverandSocial Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art: Family Tree: Stacked Ancestors, Y-Posts & Heavenly LaddersPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander Calder R SoloDocument108 pagesAlexander Calder R Solorataburguer100% (2)

- BOTHMER - A Predynastic Egyptian HippopotamusDocument7 pagesBOTHMER - A Predynastic Egyptian HippopotamussuperkuatePas encore d'évaluation

- A Guide to Modelling in Clay and Wax: And for Terra Cotta, Bronze and Silver Chasing and Embossing, Carving in Marble and Alabaster, Moulding and Casting in Plaster-Of-Paris or Sculptural Art Made Easy for BeginnersD'EverandA Guide to Modelling in Clay and Wax: And for Terra Cotta, Bronze and Silver Chasing and Embossing, Carving in Marble and Alabaster, Moulding and Casting in Plaster-Of-Paris or Sculptural Art Made Easy for BeginnersPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue of Sparta MuseumDocument266 pagesCatalogue of Sparta MuseumSpyros Markou100% (1)

- Engraving for Illustration: Historical and Practical NotesD'EverandEngraving for Illustration: Historical and Practical NotesPas encore d'évaluation

- Between Poetics and Practical AestheticsDocument11 pagesBetween Poetics and Practical Aestheticsvronsky84Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Priest, the Prince, and the Pasha: The Life and Afterlife of an Ancient Egyptian SculptureD'EverandThe Priest, the Prince, and the Pasha: The Life and Afterlife of an Ancient Egyptian SculpturePas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of The Ancient Near East PDFDocument312 pagesThe Art of The Ancient Near East PDFKatarinaFelc100% (1)

- The Metropolitan Museum Journal V 3 1970Document384 pagesThe Metropolitan Museum Journal V 3 1970Μάνος ΜανδαμαδιώτηςPas encore d'évaluation

- Regarding Art and Art History Art Bulle PDFDocument2 pagesRegarding Art and Art History Art Bulle PDFPhi Yen NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Coomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutDocument4 pagesCoomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutRoberto E. GarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- Art Museum Research PaperDocument9 pagesArt Museum Research Papertutozew1h1g2100% (1)

- Understanding Art People, Things, and Ideas From Ancient EgyptDocument144 pagesUnderstanding Art People, Things, and Ideas From Ancient EgyptMackks100% (1)

- Question: Assess The Evidence ForDocument9 pagesQuestion: Assess The Evidence ForJosha ChandePas encore d'évaluation

- Collectors, Collections & Collecting The Arts of China: Histories & ChallengesDocument3 pagesCollectors, Collections & Collecting The Arts of China: Histories & ChallengesKRISNAVENYPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Wood CarvingDocument20 pagesHistory of Wood CarvingmagusradislavPas encore d'évaluation

- Aegean Archaeology, Hall, 1915Document360 pagesAegean Archaeology, Hall, 1915Caos22Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Addressing SleeveDocument3 pagesThe Addressing SleeveKiki FuPas encore d'évaluation

- Kassel ApollonDocument16 pagesKassel ApollonDemosthenesPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF BanneredDocument7 pagesPDF BanneredmaplecookiePas encore d'évaluation

- Aeschylus in SicilyDocument13 pagesAeschylus in SicilyAriel AlejandroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lord of The Smoking Mirror' Objects Associated With John Dee in The British MuseumDocument11 pagesThe Lord of The Smoking Mirror' Objects Associated With John Dee in The British MuseumManticora MvtabilisPas encore d'évaluation

- Hollowell Hero-HawkReviewEssay 000Document9 pagesHollowell Hero-HawkReviewEssay 000María Alba BovisioPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasures From Romania at The British MuseumDocument3 pagesTreasures From Romania at The British MuseumPredrag Judge StanišićPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Art Research PaperDocument8 pagesGreek Art Research Paperegtwfsaf100% (1)

- Ars Vitraria Glass in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtDocument72 pagesArs Vitraria Glass in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPeppermintrosePas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of SculptureDocument6 pagesDefinition of SculptureErwin Roquid IsagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece and Rome Fitzwilliam MuseumDocument9 pagesGreece and Rome Fitzwilliam Museumleedores100% (2)

- Gombrich The Museum: Past Present and FutureDocument23 pagesGombrich The Museum: Past Present and FuturerotemlinialPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake / by Edward T. NewellDocument91 pagesThe Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake / by Edward T. NewellDigital Library Numis (DLN)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Braund & Hall 2014 Gender, Role and PerformerDocument11 pagesBraund & Hall 2014 Gender, Role and PerformerCeciliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rew. Middle Kingdom Art in Egypt by Cyril AldredDocument2 pagesRew. Middle Kingdom Art in Egypt by Cyril Aldredsychev_dmitryPas encore d'évaluation

- The Reserve Heads Some Remarks On TheirDocument17 pagesThe Reserve Heads Some Remarks On Theirhelios1949Pas encore d'évaluation

- Black PerseusDocument23 pagesBlack PerseusNikos HarokoposPas encore d'évaluation

- Jung Mehofer Mycenaean Greece BA Italy Cooperation Trade War AK2 2013Document3 pagesJung Mehofer Mycenaean Greece BA Italy Cooperation Trade War AK2 2013Anonymous q2cSeL1kPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Near Eastern Antiquities Lent by Mr. Joseph H. HirshhornDocument54 pages4 Near Eastern Antiquities Lent by Mr. Joseph H. Hirshhornjoseco4no100% (1)

- History in Ruin The Reconstructed Aesthe PDFDocument17 pagesHistory in Ruin The Reconstructed Aesthe PDFAneta Mudronja PletenacPas encore d'évaluation

- A Canaletto CuriosityDocument3 pagesA Canaletto Curiosityalfonso557Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogue of An Exhibition of Early Chinese Pottery and Sculpture PDFDocument330 pagesCatalogue of An Exhibition of Early Chinese Pottery and Sculpture PDFHo-ho100% (2)

- Constantina PortraitDocument26 pagesConstantina Portraitcab717Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Athenian AstragalosDocument3 pagesAn Athenian AstragalosSimonida Mona VulićPas encore d'évaluation

- EgyptianDocument88 pagesEgyptianHamada Mahmod100% (1)

- Module 3 Lesson 3Document18 pagesModule 3 Lesson 3Jovy AndoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Periods and SchoolsDocument24 pagesThe Periods and SchoolsSoporte CeffanPas encore d'évaluation

- Highlights TourDocument3 pagesHighlights TourKate KrisjanisPas encore d'évaluation

- Metaponto OxfordDocument12 pagesMetaponto OxfordAndrea La VegliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gods in Color Gallery Guide Arthur M Sackler Museum HarvardDocument8 pagesGods in Color Gallery Guide Arthur M Sackler Museum HarvardSandra Ferreira100% (2)

- Contrapposto: Style and Meaning in Renaissance ArtDocument27 pagesContrapposto: Style and Meaning in Renaissance ArtvolodeaTis100% (1)

- GroveDocument3 pagesGroveFilipe MartinsPas encore d'évaluation

- Panofsky RENAISSANCE-SELF-DEFINITION OR SELF-DECEPTIONDocument61 pagesPanofsky RENAISSANCE-SELF-DEFINITION OR SELF-DECEPTIONSTPas encore d'évaluation

- Butler PurvesDocument8 pagesButler PurvesmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Eratosthenes As Platonist and Poet - SolmsennDocument23 pagesEratosthenes As Platonist and Poet - SolmsennmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Jasanoff CosmopolitanDocument18 pagesJasanoff CosmopolitanmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- J. Lacan, L'étourdit (Trans. Jack W. Stone Et Al.)Document36 pagesJ. Lacan, L'étourdit (Trans. Jack W. Stone Et Al.)letourditPas encore d'évaluation

- Butler PurvesDocument8 pagesButler PurvesmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Wolfe Early Modern EpistemologiesDocument13 pagesWolfe Early Modern EpistemologiesmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- EratosthenicaDocument306 pagesEratosthenicamariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- J. Lacan, L'étourdit (Trans. Jack W. Stone Et Al.)Document36 pagesJ. Lacan, L'étourdit (Trans. Jack W. Stone Et Al.)letourditPas encore d'évaluation

- Ac 1 RSH StatementDocument10 pagesAc 1 RSH StatementmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Teach Yourself Improve Your FrenchDocument160 pagesTeach Yourself Improve Your FrenchmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- wshs01 03 LelgemannDocument15 pageswshs01 03 LelgemannmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Rich Text Editor FileDocument1 pageRich Text Editor FilemariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- AJP 132 1 MoyerDocument31 pagesAJP 132 1 Moyermariafrankie100% (1)

- A New Arabic Grammar of The Written LanguageDocument708 pagesA New Arabic Grammar of The Written LanguageMountainofknowledge100% (6)

- Crucified DaphnitasDocument18 pagesCrucified DaphnitasmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Complete French The Basics by Living Language ExcerptDocument42 pagesComplete French The Basics by Living Language Excerptmadulinanna50% (2)

- Ypsilanti LeonidasfishermenDocument8 pagesYpsilanti LeonidasfishermenmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Horaz DionysodeDocument24 pagesHoraz DionysodemariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Concept of Definition ChartDocument1 pageConcept of Definition ChartmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Collocations in Arabic and EnglishDocument19 pagesCollocations in Arabic and EnglishmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Horaz DionysodeDocument24 pagesHoraz DionysodemariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Dionysos RevengeDocument19 pagesDionysos RevengemariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Dithyrambic Language and Dionysiac CultDocument21 pagesDithyrambic Language and Dionysiac CultmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Category HeadingsDocument1 pageSample Category HeadingsmariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Anna Karenina by Leo TolstoyDocument579 pagesAnna Karenina by Leo TolstoyBooks100% (6)

- Accountable Talk SourcebookDocument65 pagesAccountable Talk SourcebookCarlos RabelloPas encore d'évaluation

- As First Greek Writer KEY DraftDocument34 pagesAs First Greek Writer KEY DraftcerberusalexPas encore d'évaluation

- Using German SinonymsDocument347 pagesUsing German SinonymsMerjell91% (33)

- Man in The Middle VoiceDocument213 pagesMan in The Middle VoicemariafrankiePas encore d'évaluation

- Datasheet PIC1650Document7 pagesDatasheet PIC1650Vinicius BaconPas encore d'évaluation

- Taxation During Commonwealth PeriodDocument18 pagesTaxation During Commonwealth PeriodLEIAN ROSE GAMBOA100% (2)

- Ijara-Based Financing: Definition of Ijara (Leasing)Document13 pagesIjara-Based Financing: Definition of Ijara (Leasing)Nura HaikuPas encore d'évaluation

- Ozone Therapy - A Clinical Review A. M. Elvis and J. S. EktaDocument5 pagesOzone Therapy - A Clinical Review A. M. Elvis and J. S. Ektatahuti696Pas encore d'évaluation

- Corporation True or FalseDocument2 pagesCorporation True or FalseAllyza Magtibay50% (2)

- Ukg HHW 2023Document11 pagesUkg HHW 2023Janakiram YarlagaddaPas encore d'évaluation

- B Blunt Hair Color Shine With Blunt: Sunny Sanjeev Masih PGDM 1 Roll No.50 Final PresentationDocument12 pagesB Blunt Hair Color Shine With Blunt: Sunny Sanjeev Masih PGDM 1 Roll No.50 Final PresentationAnkit Kumar SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA Negotiable Instruments Act 1881 F2Document72 pagesMBA Negotiable Instruments Act 1881 F2khmahbub100% (1)

- Eris User ManualDocument8 pagesEris User ManualcasaleiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 - Practice QuestionsDocument2 pagesChapter 2 - Practice QuestionsSiddhant AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Commerce Lecture NotesDocument572 pagesE-Commerce Lecture NotesMd Hassan100% (2)

- 1 Mile.: # Speed Last Race # Prime Power # Class Rating # Best Speed at DistDocument5 pages1 Mile.: # Speed Last Race # Prime Power # Class Rating # Best Speed at DistNick RamboPas encore d'évaluation

- Computer Education in Schools Plays Important Role in Students Career Development. ItDocument5 pagesComputer Education in Schools Plays Important Role in Students Career Development. ItEldho GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Katyusha Rocket LauncherDocument7 pagesKatyusha Rocket LauncherTepeRudeboyPas encore d'évaluation

- Sperber Ed Metarepresentations A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveDocument460 pagesSperber Ed Metarepresentations A Multidisciplinary PerspectiveHernán Franco100% (3)

- Condo Contract of SaleDocument7 pagesCondo Contract of SaleAngelo MadridPas encore d'évaluation

- With Us You Will Get Safe Food: We Follow These 10 Golden RulesDocument2 pagesWith Us You Will Get Safe Food: We Follow These 10 Golden RulesAkshay DeshmukhPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cornerstones of TestingDocument7 pagesThe Cornerstones of TestingOmar Khalid Shohag100% (3)

- CHAPTER 15 Rizal's Second Journey To ParisDocument11 pagesCHAPTER 15 Rizal's Second Journey To ParisVal Vincent M. LosariaPas encore d'évaluation

- SPM Bahasa Inggeris PAPER 1 - NOTES 2020Document11 pagesSPM Bahasa Inggeris PAPER 1 - NOTES 2020MaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Bank For Biology 7th Edition Neil A CampbellDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Biology 7th Edition Neil A Campbellpoupetonlerneanoiv0ob100% (31)

- Do 18-A and 18 SGV V de RaedtDocument15 pagesDo 18-A and 18 SGV V de RaedtThomas EdisonPas encore d'évaluation

- VDOVENKO 5 English TestDocument2 pagesVDOVENKO 5 English Testира осипчукPas encore d'évaluation

- Portales Etapas 2022 - MonicaDocument141 pagesPortales Etapas 2022 - Monicadenis_c341Pas encore d'évaluation

- NLP - Neuro-Linguistic Programming Free Theory Training Guide, NLP Definitions and PrinciplesDocument11 pagesNLP - Neuro-Linguistic Programming Free Theory Training Guide, NLP Definitions and PrinciplesyacapinburgosPas encore d'évaluation

- Distribution Optimization With The Transportation Method: Risna Kartika, Nuryanti Taufik, Marlina Nur LestariDocument9 pagesDistribution Optimization With The Transportation Method: Risna Kartika, Nuryanti Taufik, Marlina Nur Lestariferdyanta_sitepuPas encore d'évaluation

- Dua e Mujeer Arabic English Transliteration PDFDocument280 pagesDua e Mujeer Arabic English Transliteration PDFAli Araib100% (2)

- Problematical Recreations 5 1963Document49 pagesProblematical Recreations 5 1963Mina, KhristinePas encore d'évaluation

- IPASO1000 - Appendix - FW Download To Uncurrent SideDocument11 pagesIPASO1000 - Appendix - FW Download To Uncurrent SidesaidbitarPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 5 Class 2Document33 pagesWeek 5 Class 2ppPas encore d'évaluation

- Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernD'EverandTwelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (9)

- Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireD'EverandByzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (138)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsD'EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (9)

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume ID'EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (78)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedD'Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (111)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingD'EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeD'EverandThe Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodePas encore d'évaluation

- Giza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyD'EverandGiza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to ConstantineD'EverandTen Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to ConstantineÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (114)

- Caligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeD'EverandCaligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (16)

- Gnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionD'EverandGnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (132)

- The Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthD'EverandThe Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (17)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireD'EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (59)

- Pandora's Jar: Women in the Greek MythsD'EverandPandora's Jar: Women in the Greek MythsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (256)

- Past Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersD'EverandPast Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingD'EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyD'EverandGods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (42)

- The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaD'EverandThe Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (6)

- The Book of the Dead: The History and Legacy of Ancient Egypt’s Famous Funerary TextsD'EverandThe Book of the Dead: The History and Legacy of Ancient Egypt’s Famous Funerary TextsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (49)

- The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneD'EverandThe Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (32)

- The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at ActiumD'EverandThe War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at ActiumÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (34)

- Nineveh: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Assyrian CapitalD'EverandNineveh: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Assyrian CapitalÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (44)

- The book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansD'EverandThe book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (7)

- Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian HistoryD'EverandBullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian HistoryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (57)