Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Tex Design of India

Transféré par

hazarikaahmedDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Tex Design of India

Transféré par

hazarikaahmedDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

Research Article

Creation and exploitation of new Textile designs derived from Kashmiri Namda and Gabba Motifs.

1

1

Safina Latif * and 2Romana Yasmin Khan

Department of Arts & Design University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad 2 Department of Art and Design Hazara University, Mansehra.

*Corresponding Authors Email: Safina_textile@yahoo.com, roma_opensea@hotmail.com

Abstract In Kashmiri and especially in Azad Kashmir Namdas & Gabbas are prepared with unique traditional motifs. In this work transfer these matchless motifs on the cloth to produce new textile designs. This was a new addition in the textile designs. These designs appeared quite splendid and acknowledged by the experts in the textile industry. Keywords: Namda, Gabba, Kashmir, textile.

Introduction The Handicrafts of any nation are the personal index to the people who live in it. Due to rapid industrialization crunch such crafts have been axed. The mass machine products are cheaper to produce and saves a lot of time too. The handicrafts industry works on the same principle as mechanized industry which produces new models to lure more buyers. The author belongs to an area, which is worlds famous for its exquisite and fine handicrafts produced over the countries, therefore it was decided to inject new life into Namda & Gabba motifs by taking it into a different phase i.e to transfer these motifs on the cloth and to produce new textile designs. This pioneer method will give this traditional craft a larger breathing area and would definitely increase the life span by many folds. The traditional Kashmir homes include a living area where the sitting arrangement is done on the floor in a typical oriental style. This floor arrangement is amply depicted in many miniature painting where royalty is shown quartered on lavish carpets and huge round the cylindrical cushions with extravagant covering (Young, 1991). The floor covering in Kashmir is also due to the extreme cold weather where it become necessary to overcome the sub-zero temperature. The woolen rugs, namdas and gabbas are made of wool to provide warmth to the occupants. HISTORY OF NAMDA AND GABBA The art of felting sheep fleece to form namdas to serve as flow covering process saddle blankets, and wall hangings was known in Pakistan territories about 2500 years ago. These namdas can be plain or decorated with complex patterns. Some of these motifs have been in use ever since they were brought to the land by the Aryans from Central Asia while others developed in Kashmir. The more important centres of namda production with such motifs are in Swat, Hyderabad and the north western parts of Baluchistan. Another common decorative style of namdas consists of chain stitch embroidery. Woolen yarn in different colours is used on white or dyed felt to trace geometric or animal motifs or stylish patterns representing Platenus orientalis leaves, grapes, irises, almond and cherry blossoms. The craft is traditional to Kashmir and the present day centres area in Azad Kashmir, Murree, Rawalpindi, Lahore and Peshawar. Considerable impetus to the crafts was given by the creation of training centres for namda makers in Muzaffarabad and Kahuta (Amin, 1990). For more intricate than the motifs on namda are the chain stitched patterns on blankets and durlap called gabbas. In most cases the ground is completely covered with geometric or floral patterns, scenes of natural beauty or pictorial stories such as hunting scenes, wedding parties and celebrations. In recent years younger craftsmen have produced gabbas with chain stitched embroidery in wool on jute that possess all the qualities masterpieces.

www.gjournals.org

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

Namdas Namdas are felted mats made from sheep fleece. The fleece is scoured, teased and fluffed. The contemporary workshops use a carding machine to prepare the fleece but until recently, the painja, a wooden tool resembling a large bow, was used to beat and fluff large quantities of wool. The fluffed fleece is piled on a large burlap cloth in the required size. The fringes are created by placing separate tufts of fleece along the edges. The mass of fleece is sprinkled with soapy water and rolled and kneaded until the layers of wool are felted. The namda is then soaked in a large cauldron of water and finally laid flat to dry in the sun. Since the techniques is so primitive it can be assumed that it is the same process as was used in ancient times (wells, 2000). Felted products are an integral part of nomadic life in the northern and central Asian steppes and probably the technique was first discovered in Central Asia. th Nomadic Scythians lived in felted tents in the 5 century B.C. as the Kazakh nomads in Central Asia, th particularly in Sinkiang, still do today. In the late 4 century B.C. Nearchus mentions that the technique of felting was known in regions now Pakistan. Namdas were probably introduced to Pakistan as saddle blankets by the Aryans from Central Asia during the iron age. Although their early decorative elements are undocumented, it can be surmised that the types of namdas still crafted as saddle blankets and mats, as in Swat, the Hyderabad District of Sind and Lasbela, Kharan and Mastung in Baluchistan, are reflective of this influence. The Pazyryk th th finds in the Altai region of the U.S.S.R. circa 5 to 4 centuries B.C. show that the same technique of felting an assortment of dyed fleece into complex decorative patterns, as employed in the Pakistani saddle blankets, was already well developed. Some or their motifs reflected Chinese influence. This particular technique remains traditional to Turkistan, the Subcontinent, as well as Tabriz in Iran, near Western Central Asia. These second decorative style of namdas, characteristics of Kashmir, employs chain stitch embroidery and reflects Eastern Central Asian influence. Chain stitched namdas are still common in Sinkiang. The multicoloured woolen yarns are hooked through the namda with the ara-kung, the Kashmiri tool used for chain stitching. Geometric and animal motifs and flora scrolls of chenar leaves, grapes, irises, almond and cherry blossoms are popular decorative elements. A document early mentioning the namda in Eastern Central Asia was rd found in the Khotan excavations in Sinkiang dating back to the 3 century A.D. It is mentioned that namdas were th also imported into the subcontinent by way of Leh in Kashmir during the 19 century (Hamid, 1989). These namdas might have been produced in Pakistan during the Moghul Period when Kashmiri crafts flourished in Lahore. However, their contemporary commercial production started with the migration of Kashmiri Muslim craftsmen to Azad Kashmir and Pakistan during the partition. Main commercial production points are in Azad Kashmir, Rawalpindi, Lahore, Karachi and Peshawar. The first small industries training centre for namdas was established in Muzaffarabad and new centres, as in the Punjab at Kahuta, mark the future trend to support and develop the namda cottage industry (Rabbani,1991). Gabbas Gabbas are chain stitched mats embroidered originally on old blankets and woolens. They are also used as bedcovers. When there was a shortage of woolen blankets in Azad Kashmir in the sixties, the government introduced burlap and canvas as a substitute. Whereas the traditional blanked gabba sometimes exposes the blanket as background for the composition, burlap gabbas are completely covered with embroidery like the antique examples on coarse cloth. Gabbas are decorated with the popular namda motifs. Anbtique Kashmiri gabbas, with a central composition surrounded by borders, were as intricate as finely knotted carpets. Similar contemporary productions but with coarser stitches are filed with exciting ethnic compositions. Recently narrative stories such as wedding, hunting and farm scenes are added to the more traditional animal and floral compositions and nature landscapes (Hamid, 1989). Although there is no historical documentation to indicate the earliest date for the gabba craft, the concept of creating a narrative sequence by completely covering a base cloth with chain stitchery was employed in the Buddhist monastic silk embroideries of 525 A.D. The thousand Buddhas example was found in a Buddhist shrine between Khotan and Tun Huang in Sinkiang along the ancient Silk Route, which extended through Kashmir to Pakistan. Its sophisticated composition and perfected craftsmanship, however, suggest that this technique is much older (Feliceia, 1977). Gabbas are becoming an increasingly popular craft and are marketed in the local bazaars throughout Pakistan and Azad Kashmir. Because of the current demand many namda workshops are also including gabbas in their productions. The namda training centres in Azad Kashmir and the Punjab are staffed with Kashmiri master craftsmen who teach the gabba craft and the government plans to expand this production. The gabba is also proving to be a valuable export product.

www.gjournals.org

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

HISTORY AND TRADITION OF BATIK The word Batik is Indonesian in origin, but the concept itself was probably first devised either by the Egyptians or, according to other scholars, on the Indian archipelago. It is known that liquid or paste starch resists preceded the use of wax. About 300 or 400 A.D Indian traders and merchants introduced the technique to the Javanese people of Indonesia, who developed it in their own unique manner to the very high degree of excellence so admired today. Since the textile arts were of great importance to these people, the batiks of Indonesia give us an unusually complete and unbroken tradition that can be traced for centuries (Yates, 1986). The Javanese, because of their ancient batik tradition, favored cotton. Cotton was easy to grow and in a tropical climate, a comfortable fabric to wear. Batik decoration was used only on garments, rather than ceremonial cloths or decorative hangings. At one time a sultan decreed that batik making was a royal art to be practiced only by the women of the court. This ruling, of course, could not be enforced for long, the craft was too deeply ingrained among the people, but it serves as evidence of the value and high regard given these garments (Belfer, 1992). Where does batik come from? There is no certainty, but several theories speculate on the origins of this intriguing craft. The word batik is Indonesian in origin, but the concept itself was probably first devised either by the Egyptians or, according to other scholars, on the Indian archipelago. It is known that liquid or paste starch resists preceded the use of wax. About 300 or 400 A.D Indian traders and merchants introduced the technique to the Javanese people of Indonesia, who developed it in their own unique manner to the very high degree of excellence so admired today. Since the textile arts were of great importance to these people, the batiks of Indonesia give us an unusually complete and unbroken tradition that can be traced for centuries. The Javanese, because of their ancient batik tradition, favored cotton. Cotton was easy to grow and in a tropical climate, a comfortable fabric to wear. Batik decoration was used only on garments, rather than ceremonial cloths or decorative hangings. At one time a sultan decreed that batik making was a royal art to be practiced only by the women of the court. This ruling, of course, could not be enforced for long, the craft was too deeply ingrained among the people, but it serves as evidence of the value and high regard given these garments. MATERIAL AND METHOD Since the inception of man he has been trying to cover his naked body, initially with natural material and later with man made materials. Over the ages man has been able to produce cloth from natural fibers and with the passage of time with synthetic material too. The natural urge of man to decorate plain surfaces has compelled him to cover and decorate the cloth by different techniques. The different techniques have been perfected and the experimentation of refinement has been carrying on. Two or more techniques, at times, have also been merged to create new ideas. The need to create newer versions, in terms of designs and techniques, has kept textile designing on the move. In the west apparel designing has broken new frontiers, the designer have been imaginative and have tried different materials to adorn the human bodies. In Pakistan textile is the target industry due to massive cotton growth. The picked cotton after grading, is spun in to yarns of different self-patterned weaves through the use of jacquard and dobby attachments. The plain cloth thus produced either goes through a dyeing process or it is printed in different techniques according to the end use of the cloth. The authors idea of transferring the morifs of Namda and gabba in original or stylished form through four different techniques, is explained in the following text, however there are seven major techniques to decorate the textile surface, screen printing, block printing, stencil, weaving, college, dye-batik and tie and dye. The finished product, through these four design techniques, have been converted on to cloth measuring the exact length which is needed for the local Shalwar, Kameez and Dopatta. SCREEN PRINTING As in all forms of silk screening a stencil is used to print the pattern. To make a silk screen the stencil is adhered to a fine and porous silk or synthetic cloth tautly stretched over a wooden frame. With the stencil placed on top of the cloth to be printed the wooden frame, facing upwards, becomes the receptacle for the dye. Then the dye, added to a thick creamy base, is poured at the edge of the frame and evenly spread over the entire screen with a squeegee, a rubber edged wooden implement. The cloth is printed as the dye penetrates through the silk and the pattern of the stencil. The process is repeated to print the entire cloth. Separate screens are used for each additional pattern and colour (wells, 2000). A photo silk screen is made with a stencil prepared from a photo-sensitive film. In this process the stencil is made after the film is adhered to the screen. A black or opaque contour on translucent acetate or a black www.gjournals.org 10

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

image on high contrast line-film is then placed on top of the photo-sensitive film. After being exposed to light and chemical processing the unexposed areas under the black image wash away to create the stenciled silk screen. Although photo silk screening is international the local workshops and their patterns are unique. The printing is done on long outdoor padded tables where hundreds of yards of cloth are stretched to be printed and dried. Some of the prints contain as many as five colours, which are registered with separate screens. It is astonishing to see the fine quality, which can be produced with such simple facilities (Wells, 2000). BLOCK PRINTING The Subcontinents ancient techniques of applying designs on textiles with pigments and dyes, such as the oldest painting chintzes and printed calicoes, are admired as one of the greatest achievements in the Textile Arts. In fact, both moderating (using fixing agents) and printing seem to have been discovered in the Subcontinent. The flowered garments made of filmy muslim, mentioned in Megasthenes account of the Subcontinent during the 4th century B.C., were probably printed. The earliest known prints in China were imported from the Subcontinent in st 140 B.C. It is certain that printed cloth was exported to Egypt since the 1 century and they also imported printing th stamps from the Subcontinent in the 4 century. The Romans valued Indian prints and this technique spread from the Moghul Period production and export grew and an impact on the textile designs of Europe (Wells 2000). Pakistans block-prints can theoretically be included among the ancient crafts of the Subcontinent. It is most likely that block-printing also evolved here at an early date because the most ancient techniques are still practiced in Sind wehre the cotton textile industry and the part of dyeing were highly developed at the time of the Indus Valley Civilization. Terra-cotta stamps, some with designs on all six faces, probably used for printing textiles in the 1st century A.D, were excavated in Textile. Lahores calicoes and chintzes were widely exported during the Moghul th Period. In the 19 century, Multans calicoes and chintzes are noted and the chintzes from Thatta were admitted as one of the best prints produced in the Subcontinent (Yacopino, 1977). RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The stagnation in namda and gabba was the prime reason to undertake this research to infuse newer and newer surface to popularize this famous art. As the gabba and namda motifs seen in plates (A to N). The Hayward growth is generally responsible for the untimely death of many an art or at least creates a stagnation resulting in horizontal growth alone. For the vertical growth it is necessary to inject new dimension, be it design or material. The importance of scientific research has hardly found way into our traditional crafts and the handicrafts production and has always been treated as poor mans profession. This step-motherly treatment has either stopped the further growth or has totally capped the expansion. We need to create research facilities equipped with state-of-the-art technology to fully capitalize on our invisible art and craft industry. Sub-continent came to lime-slight, beside other reasons, for the fine handicrafts that this land wanted to discover the sub-continent for the fine crafts that they produced. Unfortunately our country fell prey to the greed of modern products and in the process neglected our indigenous production of handicrafts. The handcrafted and hand made items has a special feel to it, the world is still prepared to pay a lot of price for such products we need to seriously consider the prospects of this extremely prosperous and lucrative cottage industry by bringing in qualified think lanks to suggest and implement a systematic was of improving the wayward and seemingly lost industry, we have to give it a direction for the collective benefit of our economy. Namda and Gabba are just two such products which have gone astray and has been trying hard to be alive the blind fold growth has carried on till now but some day it will have to face its unnatural end if we do not help it guide into safer water. The effort to keep itself afloat will definitely get exhausted, same would be the case with other handicrafts in Pakistan. Many of the handicrafts have already met their ultimate destiny and the rest will follow suit. In the interest of the survival of the handicraft industry it is suggested that urgent attention not only for its survival but also for its growth, may be given to it, as they happen to be our personal profile about what we actually are. CONCLUSION Study the indigenous and traditional motifs of numda and gabba of Azad Jammu and Kashmir incorporate the motifs, in traditional as well as stylized form, on to apparel. Further promote and propagate the said motifs and apply different techniques in transferring the motifs on to the cloth. Rejuvenate the motifs further by giving it a different surface to expand and grow and gives the motifs larger space for its popularity. Infuse the motifs with a www.gjournals.org 11

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

new and appealing color palate and shift the motifs from ornamental dcor to utilitarian use. To create more awareness about the arts and crafts of Kashmir utilize my knowledge for the benefit of my land.

REFERENCES Hamid AA (1989). Mohsin-E-Kashmir. Lok Virsa publication, Islamabad, Pakistan. Belfer N (1992). Batik and the Dye Techniques. Third Revised Edition. Published by Constable And Co. Ltd, U.K. Amin PM (1990). Mukhtasir Tarikh-E-Kashmir. Kashmir Publication, Muzaffarabad. Rabbani GM (1991). History. Anmol Publication, Delhi. Wells K (2000). Fabrick Dyeing And Printing. Octopus Group, London. Yacopino F (1977). Threadlines Pakistan. Ministry of Industries, Government of Pakistan, Elite Publishers Ltd, Karachi. Yates MP (1986). A Hand Book For Designers. Published by Prentice Hall Press, New York. Young F (1991). Kashmir. Verinag Publication, Mirpur, Azad Kashmir.

Numda Motif

A

Woollen Numdah Embroidered hunting design

www.gjournals.org

12

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

B

.

D

Wolln Numdah embrioded round

Gabba Motif

www.gjournals.org

13

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

F

Bed spread chinar design and bd spread border design

H

Bed spread border design and bed spread fish design

Kashmiri Textile Design

Original kashmiri pattern ( Apparl in poster color) www.gjournals.org 14

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

J

Curtain design(poster color)

K

Block printing design

Cloth Work

L

Batik Print

www.gjournals.org

15

Greener Journal of Art and Humanities

ISSN: 2276-7819

Vol. 2 (1), pp. 008-016, March 2012.

M

Screen Print( Apparel)

N

Block Print( shirt piece)

www.gjournals.org

16

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Chipole FinalDocument26 pagesChipole FinalVân Anh Phan100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Goss Community PDFDocument16 pagesGoss Community PDFMaryanahPas encore d'évaluation

- Cosumar ReportDocument31 pagesCosumar ReportHajar JehouPas encore d'évaluation

- 2013 Global Market TiresDocument14 pages2013 Global Market TiresAnderson TracastroPas encore d'évaluation

- Summar Training ReportDocument35 pagesSummar Training ReportSuruli Ganesh100% (1)

- Solutions For Ketchup Production Lines - tcm11-41731Document16 pagesSolutions For Ketchup Production Lines - tcm11-41731Faheem AkramPas encore d'évaluation

- ERIKS Malaysia - Company Profile 2019Document23 pagesERIKS Malaysia - Company Profile 2019Amirul ShamPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Report (Naveena Textile)Document6 pagesIndustrial Report (Naveena Textile)YES UCETianPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 CW Pastry Catalog Web Test SizeDocument49 pages2016 CW Pastry Catalog Web Test SizeTrân HuỳnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company: Institute of Business and TechnologyDocument12 pagesMinnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company: Institute of Business and TechnologyMuhammad BilalPas encore d'évaluation

- Textile Pretreatment Process SequenceDocument2 pagesTextile Pretreatment Process SequenceBala SubramanianPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment: Submitted ToDocument6 pagesAssignment: Submitted ToSaad MajeedPas encore d'évaluation

- Cuchillo Five StarsDocument80 pagesCuchillo Five StarsGuillermo BloemPas encore d'évaluation

- Benz Packaging Solutions (P) LTDDocument21 pagesBenz Packaging Solutions (P) LTDManan ChopraPas encore d'évaluation

- On LuxDocument41 pagesOn Luxsabista25100% (1)

- Different Quality Parameters For TextilesDocument2 pagesDifferent Quality Parameters For TextilesRezaul Karim Tutul100% (4)

- How Woerle Family Company Became a Global Cheese Export LeaderDocument36 pagesHow Woerle Family Company Became a Global Cheese Export LeaderAbilash Iyer0% (1)

- Annadatta: Uncompromised QualityDocument18 pagesAnnadatta: Uncompromised QualityANJU PALLEPas encore d'évaluation

- Longchamp Case Analysis: Addressing Marketing, Production, and Leadership IssuesDocument8 pagesLongchamp Case Analysis: Addressing Marketing, Production, and Leadership IssuestestakPas encore d'évaluation

- Agile Product Data MGMT Process Ds 070039Document6 pagesAgile Product Data MGMT Process Ds 070039sau6181Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research Proposal On The Topic FMCG Market in ChennaiDocument7 pagesResearch Proposal On The Topic FMCG Market in Chennaialligater_00775% (4)

- RMG Industry AnalysisDocument35 pagesRMG Industry AnalysisSanjana TehjibPas encore d'évaluation

- QSC Sample Auntie Anne'sDocument5 pagesQSC Sample Auntie Anne'sAnonymous qFW8VbrexPas encore d'évaluation

- URC Case StudyDocument7 pagesURC Case StudyJoshua Eric Velasco DandalPas encore d'évaluation

- Ra 8423Document4 pagesRa 8423Daime Ebes EbesPas encore d'évaluation

- Textile InternshipDocument18 pagesTextile InternshipMonaal SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Russia Clothing Textile Sector 1Document15 pages2017 Russia Clothing Textile Sector 1FIERY TrackPas encore d'évaluation

- Shelf Life Study Introduction - AY1819Document7 pagesShelf Life Study Introduction - AY1819RaysonChooPas encore d'évaluation

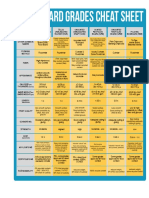

- Paperboard Grades Cheat Sheet GuideDocument1 pagePaperboard Grades Cheat Sheet GuideEva Kovač Brčić100% (2)

- A Report on Sumul Dairy, Surat: Production, Finance, Marketing and HR PracticesDocument38 pagesA Report on Sumul Dairy, Surat: Production, Finance, Marketing and HR PracticesDev JariwalaPas encore d'évaluation