Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Personhood

Transféré par

yvonne111Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Personhood

Transféré par

yvonne111Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Why is it important to consider who persons are and how they come into being?

Introduction For the Tallensi people of Ghana, certain sacred crocodilesare persons (La Fontaine, 1985: 127). This assertion challenges Western notions of personhood to the core, for in most Western societies animals cannot be people. Anthropomorphising animals in childrens cartoons is one thing, but there is a sharp distinction between animals and people in Western culture. But the crocodile provides a lucid example of the fact that not all cultures, societies, peoples view the world in Western terms. Mauss points out that the idea of a person is not innate; it is a social category which developed over centuries (1950[1985]). What began as a role that people played in society developed into a mask, a persona, something outside of the self (ibid.: 17) what a person was but had important consequences for the legal concept of the self. Only select persons had a self, slaves for example, were excluded (ibid.:17). Later, apart from legal importance, the self gained a moral dimension at which point autonomy and consciousness of ones own being led to idea about freedom and responsibility. With the advent of Christianity the self acquired a metaphysical capacity and questions about the unity of the self were raised which in turn led to the self as a psychological being (20). This evolutionary view of the self shows how what seems at first be natural and self-evident (Carrithers et al.:vii), is a fragment of history intrinsically linked to social organisation, and so particular to social context (Mauss,1938[1985]). Western conceptions of the person place the emphasis on the beginning of life and personhood is an inalienable right; conception, birth or naming are the point at which a being becomes a person and it is rare for personhood to be denied. Yet non-Western cultures perceive personhood as transition (La Fontaine, 1985: 132), and not all individuals are able to become persons because of their status in society. Furthermore, ideas to do with when a being gains person status differ from society to society. Whether a person comes into being at naming, at birth or at conception has important legal consequences. So personhood needs to be considered in order to challenge Western ideas about duality, to assess the legal implications for when a person becomes a person, and to better understand other societies concept of personhood.

Dual and composite visions Ingold (1991) argues that the Western duality which separates the biological organism, the body, from the social person is misleading. This duality posits humanity over animality(ibid.:357) but creates the problem of having a two-part person whereby the organism has to learn to be a person. In this structure as the organism grows, the person is made when the cultural form is imposed upon it, which contrasts with perceptions of animals in Western culture; animals are animals right

from the start (ibid.:358). Ingold gives the example of the baby elephant, which does not have to become elephant as it develops because it already is one (ibid.:358). A dualistic vision of personhood assumes some elements of personhood to be innate, indeed the raw experience of self-awareness is assumed as a universal fact of human nature (ibid.: 365) however this is not the case. An example of this is how speech or walking are assumed to be innate, yet cycling or writing may be seen as things which are learnt. But all facets of human development take place within a culture and if walking is universal whereas cycling is not, this is because the environment of development for the former is general, whereas the environment of development for the latter obtains only under limited circumstances (ibid.:370). Ingold points out that a distinction between biological and cultural leads to the idea that within the mother-child relationship, the nurturing can only be seen as cultural, not biological (ibid.:361). This idea seems rather strange, but it does follow the logic of a biological-cultural separation. This separation of the biological from the cultural is not present in non-Western societies. For the Melpa people the self is generated and conserved only within the total relational context of embryonic development so there is no separation of nature and culture; personhood develops within a matrix of relations with others (ibid.:362). Through his discussion of the Tallensi people of Ghana, La Fontaine shows that a person can be a composite (ibid.:126) of material and immaterial, and that emotions are connected to parts of the body, or for the Taita where social aspects are located within the organs of the body (ibid.:128). All of this clearly questions Western assumptions about nature and culture. Perhaps this duality is not the best way to view the development of social beings, it is certainly not the only view. The 'when' of personhood Another Western idea about the self is that a person comes into being at birth, or before. For the Tallensi, personhood is connected to the life path of a person and it is the completion of a proper life which qualifies an individual for full personhood(ibid.:131) because of which some individuals may not be granted personhood if they do not go through certain life-cycle rituals, such as marriage or having children. Personhood, then, is not a universal category. Just as Mauss depiction of the Western concept of the person is particular to a Christian way of viewing the world, so personhood is embedded in a social context (ibid.:133) in all cultures. While for Westerners individuality is granted at birth through naming, for other non-Western cultures there may be a longer period through which personhood is created (ibid.: 132).La Fontaine emphasises that the concept of the individual is unique to Western thought (1985: 123), and is a concept which gives jural, moral and social significance to the mortal human being(ibid.:124). Persons exist differently across cultures. For the Jivaroan Achuans, personhood is an unstable state (Taylor, 1996:207). An individual is born in an arbitrary form, which is their body and the perception of the body by others, shapes the subjectivity of the individual. Because the sense of self is based in others reflections of that self when relations change or death occurs this sense can be disrupted. The endemic feuding and shifting alliances (ibid.:207) mean that relations

between individuals, even family members are weak, so alliances are constantly changing. Therefore there is much uncertainty as to others feelings towards oneself, so there is little sense of stability available for constructing ones own selfhood (ibid.). Taylor argues that this is the cause of illness for the Achuans, that when their sense of self becomes so uncertain because of constantly changing relationships and doubt, they lose a sense of identity(ibid.). This conceptualisation of where the self lies and how it is constructed challenges Western notions of the self as autonomous, individual and independent. Personhood and ethics While some notions of personhood simply raise questions about difference, others raise more ethically pressing points. An analysis of honour and shame can provide a study of the basic mould of social personality (Peristiany, 1965:10) in a particular society revealing the parameters within which personhood is created. When one man challenges another in Kabyle society, there is a mutual recognition of equality (Bourdieu, 1965: 199) that is, the challenged must be equal in honour and recognised as a peer by the challenger (ibid.: 199). The challenge itself gives one the sense of existing fully as a man (ibid.:199). Through mutual recognition equality is created and each individual is understood to be a person equal to the other. A mans honour can be damaged in certain circumstances such as responding to the insults of a negro (ibid.:200) because in Kabyle society black people were considered bereft of honour(ibid.) and so inferior. Recognition as a person, as an equal is not permitted to all members Kabyle society. Personhood is associated with honour therefore it is created and maintained throughout life, not automatically granted at birth. James (2000)stated that peri-natal time is regarded by many as purely biological. James discusses several non-Western ideas about conception and birth with a view to considering abortion and infanticide. She criticises early anthropological accounts of non-Western woman without morality or feeling, she was represented as easily and innocently disposing of any foetus or infant surplus to requirements (ibid.:175). She draws attention to differing ideas about the source of the child as being outside parental or even human control (ibid.:186), the point at which a foetus is recognised as a person, and the preparations made in the social sphere for the unborn child. For the aboriginal people of the Kimberley Division of Western Australia a conception is caused by a man giving a woman fertile-food (ibid.: 173) which contains a spirit-child (ibid.) of a dead ancestor. The point of her discussion is that the recognition of a child has implications for a legal considerations about abortion and infanticide. She argues that despite culturally specific beliefs scientific knowledge about the foetus should be used to inform legal and ethical frameworks. Both these accounts force us to consider at what point a person comes into being and whether this how cultural beliefs should fit into a wider ethical framework. A society in which the belief system permits racism or infanticide does not sit easily with Western ethics. Conclusion

That personhood is a social construct is an important idea for anthropologists to grasp. A concept that seems so fundamental, perhaps universal is demonstrably a social construct and should be viewed as such. Allen asks whether Mauss personnage, or role was really a mirage?(1985: 41) highlighting just how embedded in social interpretation is the concept of personhood. She also points out that most societies do not fit neatly into opposing categories and that it is a complex concept in all societies. Even the Western idea of personhood is still imprecise, delicate and fragile (Mauss, 1938[1985]: 1) as La Fontaine demonstrates it is the society and nature of authority within a society which shape ideas about the person. In short, by examining personhood we are dealing with the interpretation of behaviour, practices, institutions and everyday beliefs in order to unearth underlying, and often acknowledged, assumptions (Lukes, 1985: 291) and as anthropologists we should be ready to question all our assumptions no matter how fundamental they may seem. References Allen, N.J. 1985 The category of the person: a reading of Mauss' last essay. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins, & S. Lukes 1985. The category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp.26-45 Bourdieu, P. 1965. The sentiment of honour in Kabyle society. In J.Peristiany (Ed.) Honour and Shame. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson Carrithers, M., Collins. S., Lukes, S. Preface. 1985. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins, & S. Lukes (Eds.)1985. The category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. vii-viii La Fontaine, J.S. 1985. Person and individual: some anthropological reflections. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins, & S. Lukes (Eds.)1985. The category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 123-140 Lukes, S. 1985 Conclusion. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins, & S. Lukes (Eds.) 1985. The category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 282-301 Mauss, M. 1938[1985] A category of human mind: the notion of person; the notion of self. Translated by W.D. Halls. In M. Carrithers, S. Collins, & S. Lukes (Eds.) 1985. The category of the person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp.1-25 Ingold, T. 1991. becoming persons: consciousness and sociality in human evolution. In Cultural Dynamics 4(3) 355-78 James, W. 2000. Placing the unborn: on the social recognition of new life. In Anthropology & Medicine 7(2)169-89 Taylor, A.C. 1996. The soul's body and its states: an Amazonian perspective on the nature of being human. In The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute incorporating Man 2, 210-215

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- China's Use of Perception Management and Strategic Deception November 2009Document68 pagesChina's Use of Perception Management and Strategic Deception November 2009lawrence100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Wanderer: A Text From the Saxon-Norman Wars in EnglandDocument189 pagesThe Wanderer: A Text From the Saxon-Norman Wars in EnglandcimpoctePas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- GIA Pretest BookletDocument17 pagesGIA Pretest BookletSoborin Chey100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Wily Walnut BRAIN SQUEEZERS Vol.1Document116 pagesWily Walnut BRAIN SQUEEZERS Vol.1tarzaman88% (8)

- The Grand DesignDocument10 pagesThe Grand DesignDavePas encore d'évaluation

- Waldron Buddhist Steps To An Ecology of MindDocument63 pagesWaldron Buddhist Steps To An Ecology of MindzhigpPas encore d'évaluation

- Sensation and Perception Review PacketDocument16 pagesSensation and Perception Review Packetapi-421695293Pas encore d'évaluation

- Raymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDocument38 pagesRaymond Trevor Bradley - The Psychophysiology of Intuition: A Quantum-Holographic Theory of Nonlocal CommunicationDominos021100% (1)

- 9D-NLS Use ManualDocument98 pages9D-NLS Use ManualVanda Leitao60% (5)

- Program Outcomes and Learning OutcomesDocument18 pagesProgram Outcomes and Learning OutcomesApril Claire Pineda Manlangit100% (3)

- Amanda BaggsDocument7 pagesAmanda Baggsapi-385249708Pas encore d'évaluation

- BobathDocument28 pagesBobathSaba SamimPas encore d'évaluation

- Responsive EnvironmentsDocument78 pagesResponsive Environmentsfrancescleo8duran83% (6)

- Writing 1 Advanced 11 - Natalia PortalDocument1 pageWriting 1 Advanced 11 - Natalia PortalNataliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Labov's Model of Narrative Analysis Focuses on Oral vs WrittenDocument3 pagesLabov's Model of Narrative Analysis Focuses on Oral vs Writtenyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- NarrativeDocument54 pagesNarrativeyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interantional Historical Geography AbstractDocument1 pageInterantional Historical Geography Abstractyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nomadic Passages in a Woman Artist's MemoirDocument19 pagesNomadic Passages in a Woman Artist's Memoiryvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz 1 - ADocument1 pageQuiz 1 - Ayvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- SA Crib SheetDocument1 pageSA Crib Sheetyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Happiness Czech English Estudios en LC - Dictamen - ComentariosDocument18 pagesHappiness Czech English Estudios en LC - Dictamen - Comentariosyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Women's Veil as a Symbol of Social Separation and ControlDocument17 pagesWomen's Veil as a Symbol of Social Separation and Controlyvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

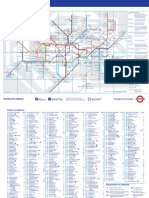

- Standard Tube MapDocument2 pagesStandard Tube MapgoldcupcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of Purpose - 11.01.12Document2 pagesStatement of Purpose - 11.01.12yvonne111Pas encore d'évaluation

- City of Antipolo Institute of Technology: Senior High SchoolDocument6 pagesCity of Antipolo Institute of Technology: Senior High SchoolkurtPas encore d'évaluation

- Preservice Primary Teachers and Mathemat PDFDocument209 pagesPreservice Primary Teachers and Mathemat PDFKidus HunPas encore d'évaluation

- Narayanalakshmi: Translation and ExplanationDocument90 pagesNarayanalakshmi: Translation and ExplanationantiX LinuxPas encore d'évaluation

- Livingstone-Making Sense of Television - The Psychology of Audience Interpretation - Routledge (1998) PDFDocument224 pagesLivingstone-Making Sense of Television - The Psychology of Audience Interpretation - Routledge (1998) PDFSandro MacassiPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Behavior Chapter 1-3Document14 pagesConsumer Behavior Chapter 1-3Angeline GambaPas encore d'évaluation

- François Bayle - Space - and - MoreDocument9 pagesFrançois Bayle - Space - and - MoreDaniel TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tonic FunctionDocument9 pagesTonic FunctionleoPas encore d'évaluation

- CARES Project Complete ReportDocument64 pagesCARES Project Complete ReportiBerkshires.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Safety Climate in University and College Laboratories: Impact of Organizational and Individual FactorsDocument12 pagesSafety Climate in University and College Laboratories: Impact of Organizational and Individual Factorsmnazri98Pas encore d'évaluation

- International Management Culture Strategy and Behavior 9th Edition Luthans Solutions ManualDocument32 pagesInternational Management Culture Strategy and Behavior 9th Edition Luthans Solutions Manualchuseurusmnsn3100% (28)

- HCI LabFile Mahima Verma F9 02015603117Document32 pagesHCI LabFile Mahima Verma F9 02015603117swatiPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL English-6 Q1 W12022-2023Document52 pagesDLL English-6 Q1 W12022-2023Chiara Margarita Dogos RosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sat Practice Test 10 Reading Answer Explanations atDocument45 pagesSat Practice Test 10 Reading Answer Explanations atCarla bPas encore d'évaluation

- SME and Large Organisation Perceptions of Knowledge Management: Comparisons and ContrastsDocument11 pagesSME and Large Organisation Perceptions of Knowledge Management: Comparisons and Contraststedy hermawanPas encore d'évaluation

- Skyrim Mod NotesDocument10 pagesSkyrim Mod NotesTalon BloodraynPas encore d'évaluation

- Gordons 11 Functional PatternDocument3 pagesGordons 11 Functional PatternMaha AmilPas encore d'évaluation