Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Creating Classroom Rules For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: A Decision-Making Guide

Transféré par

Mary ChildDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Creating Classroom Rules For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: A Decision-Making Guide

Transféré par

Mary ChildDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

Creating Classroom Rules for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: A Decision-Making Guide

Douglas E. Kostewicz, University of Pittsburgh Kathy L. Ruhl AND Richard M. Kubina Jr, The Pennsylvania State University

high degree of teacher turnover occurs within the educational system, with exiting teachers often crediting student misbehavior as a contributing factor (Buckley, Schneider, & Shang, 2005; Eberhard, ReinhardtMondragon, & Stottlemyer, 2000; National Education Association, 2003). The behaviors of one population, students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD), often present significant challenges for classroom teachers (Kauffman & Wong, 1991). Based on these behaviors, educators often characterize students with EBD as aggressive, disruptive, or off task (Sutherland & Singh, 2004). Such behaviors may occur concomitant with, or as a result of, shortfalls in expressive or receptive language functioning (Benner, Nelson, & Epstein, 2002). These language deficits may exacerbate both social interaction and academic performance problems as students with EBD fail to understand events or are hindered in their communicative skills (Ruhl, Hughes, & Camaratra, 1992). Displaying low academic proficiency, students with EBD receive some of the lowest grades of any group of students with or without special needs, and as a result, students with EBD maintain a very high drop-out rate (Sutherland & Singh, 2004). Given the challenging nature of learners with EBD, one question begs asking: How can teachers who serve students with EBD respond so that students with EBD can function effectively regardless of setting? One answer lies in classroom management and structure.

Students with EBD receive services in a variety of settings (e.g., resource, self-contained, and inclusive classrooms), and the absence of clear structure in any of these settings negatively affects learning and effective behavior plans (Malone, Bonitz, & Rickett, 1998; Steinberg & Knitzer, 1992). Unlike effective teachers who monitor classroom behavior, provide clear expectations (e.g., classroom rules), and promote student accountability for meeting those expectations (Stevenson, 1991), some teachers of students with EBD fail to use effective classroom management techniques (Sutherland & Wehby, 2001). Rules, which might be considered one form of communicating expectations, may constitute the most cost-effective form of classroom management and play an important role (Bicard, 2000). Rather than viewing rules as elements of control, rules might best be conceptualized as contributing to a classroom environment conducive to learning. Through teacher presentation of rules, students learn boundaries for classroom behavior and the Dos and Donts of classroom life (Boostrom, 1991). Importantly, rules may help students with language problems better understand expectations and set the stage for positive environmental influences for effective classroom behaviors. As an important aspect of classroom management systems, rules play a major role and bear heightened significance for teachers serving students with EBD. However, creating effective rules requires careful thought and effort. This paper presents six questions facing teachers

as they create classroom rules and recommendations for effective rule creation, while addressing specific concerns for those who serve students with EBD. Six Rule DecisionMaking Questions Teachers can ask themselves six questions as they create effective classroom rules: (1) Who will participate in rule creation? (2) What behaviors will serve as the basis for the classroom rules? (3) How will I phrase the classroom rules? (4) How many rules should I use? (5) How will I communicate the rules to my students? and (6) If applicable, what will I do to support student rule compliance? Along with recommendations and considerations for students with EBD that accompany each question, we will follow Christina, a fictitious middle school teacher, as she makes rule creation decisions. During the academic year, Christina will have responsibility for a class of 25 students, 3 of whom have an EBD label. Talking with teachers from the grade below her and drawing on her own experiences, Christina identifies the need for a high level of structure in her classroom for this upcoming group of students and plans to create this structure around classroom rules. Question 1: Who Will Participate in Rule Creation? Teachers must first decide who participates in rule developmentthe teacher only or the teacher and the students. Stevenson (1991) maintains that students play an informal role in rule creation, because rules follow

Section 4 References Page 17 of 31

14 B E Y O N D B E H A V I O R

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

student and classroom needs. Bicard (2000) suggests an extension to this informal role would involve students participating in rule creation. If students have a greater hand in rule creation, they may better relate to the rules and comply more often (McGinnis, Fredrick, & Edwards, 1995); however, such an inclusive approach may be counterproductive in settings serving students with EBD for several reasons. First, students with EBD may better respond to established structure and boundaries for behavior from the moment they enter a classroom. Having clearly specified rules helps students with EBD know what they are to do. Waiting to involve them leaves many opportunities for students to engage in unacceptable behaviors as they wait for rule development. Second, establishing rules with student input may prove difficult logistically, especially considering mixed populations of those with and without EBD. Students with EBD may lack the capacity and social awareness to participate cooperatively in rule creation, thus limiting their contributions and possibly making it difficult for their peers. Third, students tend to have a harsh sense of justice and often recommend extremely strict rules (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996). While teachers will find it important to create precise, clearly worded rules and implement those rules consistently, teachers using overly restrictive rules may set students with EBD up for failure. Considering these factors, it seems prudent that teachers create an initial set of rules without student participation and then include student input as warranted. Christina made a decision to create her rules without student input and, in fact, before students arrived in her classroom. She did not, however, develop these rules without previous knowledge. She incorporated her own experiences with studentspecific knowledge garnered from teachers from earlier grades.

Understanding that unforeseen situations may arise, Christina reserves the opportunity to make minor modifications to her rules list with student input. She feels confident, however, that her rules cover both pressing and future classroom problems and enable her class to interact with the rules from the first day of school. Question 2: What Behaviors Will Serve as the Basis for the Classroom Rules? Logistics prevent a teacher from creating, teaching, and implementing a rule for every student behavior, predicted or observed. Because of the prominent nature and applicability of rules, teachers should reserve rules for minor but chronic and/or severe student behaviors. Minor aversive behaviors generally have short-term adverse effects on the environment. Over time, however, these minor behaviors can cumulatively add up to cause a more significant impact on the environment. For example, one call-out every period may not adversely affect the classroom or cause physical harm, but multiple call-outs every few minutes may prove very disruptive. While possibly occurring with less frequency, severe behaviors can have immediate and dangerous effects on the classroom and those in the classroom. Some examples of severe behaviors include property destruction and physical harm to self and others. Because students with EBD often display both chronic and severe behaviors (Sutherland & Singh, 2004), teachers can target these behaviors as a foundation for classroom rules. Before Christina can address rule creation, she must determine the needs of the classroom. Christina initially chose to focus on potentially chronic and severe behaviors that her students may exhibit. These behaviors would interfere with instruction, student transitions, and may place students or others in physically dangerous situations. Based on her knowledge of the

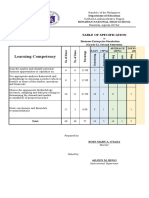

incoming class, she has identified eight possible chronic and/or severe classroom behaviors (Figure 1, Step 1). Now that she has a basis for classroom rules, she can make decisions on the remaining questions. Question 3: How Will I Phrase the Classroom Rules? The third decision regards how to word the rules. This has two aspects: rule type and rule wording specifically. Bicard (2000) describes two types of rules: positive and negative. Positive rules focus on what a student should do and help teachers concentrate on helping students acquire appropriate and useful behaviors. Negative rules state what students should not do and focus teacher attention on student misbehavior. Positive rules encourage use of positive interactions, while negative rules promote using aversives and punishment. Because a teachers primary responsibility involves creation not elimination of students behavior, many educators (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995) have promoted using positively stated rules. Using positive rules for students with EBD, who will likely benefit from a positive educative approach, may prove beneficial. As with many teachers, Christina found it easier to focus on aversive student behaviors. Without asking herself this rule creation question, she may have easily fallen into the trap of phrasing each rule in a negative manner by creating rules similar to Dont hit each other and Dont talk out, leaving a void about desirable and permissible behaviors. To avoid this, Christina can take rule phrasing one step further by asking herself, What is the desirable behavior I wish to see? and then formulating the more positively stated rule to better communicate with students. Figure 1, step 2 illustrates her revisions using this positive approach. Once changed into a positive rule, teachers must determine each S PRING 2 0 0 8

15

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

Figure 1 THIS FLOW CHART SHOWS CHRISTINAS TRANSFORMATION OF CLASSROOM NEEDS INTO CLASSROOM RULES ANSWERING RULE CREATION QUESTIONS

16 B E Y O N D B E H A V I O R

Section 4 References Page 19 of 31

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

Table 1 RULE TYPE AND WORDING

Type Wording Specific 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. Positive Raise your hand to gain the teachers attention Keep your hands and feet to yourself Have your school materials ready when needed Be courteous Be a good neighbor Be responsible 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. Negative No talk outs in class Dont hit anyone Dont fumble with your school supplies Dont bother others Dont be a meanie Dont waste time

Nonspecific

Note. Examples focus on target behaviors for (1) gaining attention, (2) minimizing inappropriate physical contact, and (3) being prepared to learn.

rules specific wording. Rules must convey meaning as effectively and efficiently as possible. Thus, teachers should avoid using vague rules that neither let the student know what to or not to do. Teachers using vague rules may find it difficult to observe rule-following behavior as the teacher and students may interpret the rule differently (Bicard, 2000; Murdick & Petch-Hogan, 1996). Conversely, explicit, briefly, and clearly worded statements foster straightforward, precise, and easy to understand and remember rules (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995). Thus, rules should focus on specific observable behaviors rather than nonspecific generalities (e.g., Raise your hand to gain the teachers attention vs. Get attention the right way) (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995). Due to a prevalence of language disorders among students with EBD, clearly worded rules promote understanding. Rules that tell students with EBD exactly how and when to behave are desirable. Table 1 shows different effective and ineffective ways to word rules targeting three areas of concern. Returning to Christina, we notice she has worded her positively phrased rules in a vague manner (e.g., Be a good neighbor, Be courteous, and Be ready to learn). For many teachers and students, especially students who present with emotional and behavior deficits, rules phrased in this manner provide too

much wiggle room leaving the rule open to different interpretations. For example, Be courteous may mean standing when a teacher enters the room, sharing food, or raising a hand to gain the teachers attention. In order to convey her intended meaning, Christina would need to reexamine her positive rules for any that appear vague and reword them to read specifically, leaving students no room for misunderstanding the expectations. Figure 1, Step 3 shows these changes. Question 4: How Many Rules Should I Use? A fourth rule creation question asks how many rules to put into practice. Boostrom (1991) recommends teachers avoid having too many rules to minimize student confusion. Fewer statements make it easier for a student to remember how they should or should not behave. However, by employing too few rules, teachers can provide too much room for student error. An optimal number of rules represented in the literature (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995) ranges between three and five. Christina noticed as she worded and reworded her classroom rules, some appeared similar and/or overlapped with others. To pare her list from eight to the suggested three to five, Christina chose to combine rules addressing similar behaviors. For example, Christina addressed

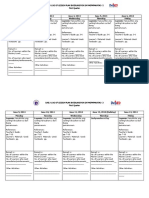

classroom challenges focusing on unnecessary student noise and excess interruptions with the simple rule, Raise your hand and gain the teachers attention. As displayed in Figure 1, Christina combines like rules (Step 4) and settles on a list of five rules following final revisions (Step 5). Question 5: How Will I Communicate the Rules to My Students? McGinnis et al. (1995) suggest increased student compliance ties into the ability of students to readily recall and recite the rules, which links directly to rule presentation. Two methods of rule presentation include publicly posting the rules and clearly teaching rules to the class (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995). Rules should be posted where all learners can observe them and in a manner that enables teachers to readily make reference to them. Younger learners and those with language difficulties may also benefit from pictorial illustrations of the rules. As with academic behaviors, teachers should present rules using effective instructional practices. One form of instruction, direct instruction, seems appropriate for students with EBD due to its explicit nature (Gunter, Coutinho, & Cade, 2002). After explaining a rules goal and importance, a teacher would model examples and nonexamples of rulefollowing behaviors. Through guided practice, each student would have the opportunity to either answer S PRING 2 0 0 8

17

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

questions about or role-play rule behaviors. Finally, the teacher would evaluate each students independent performance. This form of practice and feedback would especially benefit students with EBD who may need extra practice and attention with rule-following behaviors. Christina plans to create a permanent rules list to post in a location visible to all students. She has also prepared lessons to explicitly instruct each of the rules through examples and nonexamples. Using the first few days of school for these lessons seems especially important and feasible. First, rule instruction marks student boundaries from the start, setting the stage for an effective year. Second, rules instruction would not take up precious academic time as most academic instruction has not started. Figure 2 presents a sample lesson plan for the rule Keep your hands, feet, and objects to yourself. Question 6: If Applicable, What Will I Do to Support the Rules? This question involves two parts: rule applicability and teacher support. Teachers can decide after observing student behavior if the rules chosen apply to the current situation. Sometimes, teachers may follow effective rule creation criteria, only to have developed a rule that exceeds the ability of a student or students. Teachers can then determine if students require additional instruction on component rule-following behaviors or additional time to complete the rule (Rademacher, Callahan, & PedersonSeelye, 1998). If a teacher deems the rules applicable, then the teacher can define their own responsibilities with respect to the rules they choose to employ (Rademacher et al., 1998). For example, teachers can adjust their physical presence (i.e., where they position themselves in the classroom) when a rule-related behavior comes into play. Consider the rule, When directed, line up quietly in a straight line. Initially, the teacher could

stand by the door before directing the students to line up helping to prompt rule-following. After providing the signal to line up, the teacher would watch for students having difficulties following the rule and also the amount of time it takes for all of the students to line up. The teacher might also inform the students of the amount of time required to line up, challenging them to beat that time. Results of these observations and proactive measures can facilitate students successful rule-following. Christina understands that the skill level of many of her incoming students will differ. Knowing that some of her new students may require additional assistance and teaching, she plans to closely observe student rule-following the first 2 weeks. This will allow her to identify any preskill deficits (i.e., how to stand in line appropriately) and if she has chosen the appropriate amount of time necessary to complete a rule (i.e., sufficient assignment time). Based on her observations, she can set aside one-on-one time with certain students to practice rulefollowing behaviors using lesson plans similar in form to Figure 2. Comments on Christinas Final Rule List Lets review and critique the five rules Christina created. First she chose Keep your hands, feet, and objects to yourself. While this rule covers most physical acts of aggression, it does not promote socially acceptable forms of physical contact (e.g., high fives, shaking hands) or sharing (e.g., asking for or borrowing toys or school supplies). If necessary, Christina would have to address this with the class. The second rule Raise your hand to gain the teachers attention has both functional and portable attributes. Functionally speaking, students that raise their hand will often meet with attention, which will hopefully maintain hand raises. Christina can not only implement this

rule in the classroom, but on field trips or school assemblies requiring quiet behavior, displaying its portability. However, Christina may have her students in situations where students do not need to raise hands (e.g., classroom party, playground, field trip not requiring quiet) and would need to address these situations with her class. The third rule, When directed, line up quietly in a straight line, allows Christina to focus on almost any transition inside or outside the classroom. Some teachers may treat lining up in this manner as a routine behavior and choose not to create a specific rule. In Christinas case, she felt she needed to pay specific attention to minimizing transition problems. Based on her knowledge of her students, it seems appropriate that Christina made the rule. Also portable, the fourth rule Complete assignments on time relates to any class, academic, or special (music, art, etc.) assignment, but requires that Christina inform the students of the conclusion of the task. Finally, Christina can use the fifth rule Stay in your assigned area in almost any situation. On the playground, the assigned area may comprise the fenced in area or with the team, on a field trip, the bus, or with the group, and in the classroom, the students desk or group table. This rule also requires that Christina informs her students of the assigned area per activity. Looking at Christinas rules, she has chosen to target important and necessary behaviors for her students, phrased them in a functional manner targeting situations both inside and outside her classroom, and limited them to a manageable number of five. Additional Concerns Regarding Rule Use and Students with EBD After examining Christinas final rules list, one may note that these rules appear applicable to most students in educational settings, prompting the question Dont

Section 4 References Page 21 of 31

18 B E Y O N D B E H A V I O R

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

Figure 2 THIS SAMPLE LESSON PLAN FOCUSES ON TEACHING THE RULE KEEP YOUR HANDS AND FEET TO YOURSELF AT ALL TIME

S PRING 2 0 0 8

19

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

students with EBD need special EBD rules? The answer: they do not. Throughout the process, Christina moved through rule creation targeting the potential needs of her students and classroom. More specifically, she paid special attention to behaviors that presented dangerous situations or interrupted instruction. Teachers who create rules addressing the specific behaviors of the class and students in question do not apply special, but rather appropriate rules. So in one sense, teachers create and use rules for students with EBD just as any teacher creates and uses special rules to meet the needs of their students, suggesting the process appears no different. However, teachers should realize that for students with EBD, rules may evoke responses other than those observed from students who do not experience emotional or behavioral difficulties. Appearing aversive, rules often prompt negative reactions from students with EBD (Shores, Gunter, & Jack, 1993). In the presence of rules, students with EBD and their teachers may fall into various destructive cycles of inappropriate behavior. In response to inappropriate behavior created by the presence of rules, teachers may inadvertently maintain a cycle of coercion by using further aversive situations to control outbursts (Gunter et al., 1994). Additionally, in the presence of rules, students with EBD may avoid rulefollowing behavior altogether by escaping from academic, social, and rule demands by either behaving in ways that force their removal from the classroom or by blatant noncompliance (Shores, Gunter, & Jack, 1993; Shores, Jack, Gunter, & Ellis, 1993; Sutherland & Wehby, 2001). Teachers, who create specific and positive rules as a basis for their classroom management system create a positive environment that both facilitates rule-following behavior and helps minimize negative cycles of inappropriate behavior by shifting teacher attention from inappropriate

to appropriate student behavior (Gunter, Denny, Jack, & Shores, 1993). Once put into practice, teachers must eventually provide consistent consequences in response to rulefollowing and rule-breaking behavior (Bicard, 2000; Heins, 1996; McGinnis et al., 1995). Many have summarized guidelines for implementing consequences (Gunter et al., 2002; Landrum, Tankersley, & Kauffman, 2003; Lewis, Hudson, Richter, & Johnson, 2004) and addressed the potential problems regarding students with EBD (Gunter et al., 1993; Gunter et al., 1994; Shores, Gunter, Denny, & Jack, 1993; Sutherland & Singh, 2004). This involved process raises issues and concerns beyond the scope of this particular paper. Briefly, however, one should promote rule-following behavior by reinforcing rule compliance, delivering negative consequences for noncompliance when warranted, and doing both consistently. Conclusion Teachers in any classroom containing students with EBD often find themselves in situations that require classroom management systems. Effective rules play a vital role in their successful implementation. The process for creating effective rules for students with EBD appears to hold little difference from that used in other settings. The rule creation process focuses on the needs of learners in the classroom and pays special attention to wording and number of rules implemented. Effective decisions based on these rule creation questions may help teachers further establish a positive atmosphere for students with EBD. In turn, students may respond with an increase in rule-following behavior, assisting them to fulfill the social and academic demands of a classroom.

REFERENCES

Benner, G. J., Nelson, J. R., & Epstein, M. H. (2002). Language skills of children

with EBD: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10, 4359. Bicard, D. F. (2000). Using classroom rules to construct behavior. Middle School Journal, 31(5), 3745. Boostrom, R. (1991). The nature and functions of classroom rules. Curriculum Inquiry, 21, 193216. Buckley, J., Schneider, M., & Shang, Y. (2005). Fix it and they might stay. School facility quality and teacher retention in Washington, D. C. Teachers College Record, 107, 11071123. Eberhard, J., Reinhardt-Mondragon, P., & Stottlemyer, B. (2000). Strategies for new teacher retention: creating a climate of authentic professional development for teachers with three or less years of experience. Corpus Christi: Texas A&M University, South Texas Research & Development Center. Gunter, P. L., Coutinho, M. J., & Cade, T. (2002). Classroom factors linked with academic gains among students with emotional and behavioral problems. Preventing School Failure, 46, 126132. Gunter, P. L., Denny, R. K., Jack, S. L., & Shores, R. E. (1993). Aversive stimuli in academic interactions between students with serious emotional disturbance and their teachers. Behavioral Disorders, 18, 265274. Gunter, P. L., Denny, R. K., Shores, R. E., Reed, T. M., Jack, S. L., & Nelson, C. M. (1994). Teacher escape, avoidance, and counter control behaviors: Potential responses to disruptive and aggressive behaviors of students with severe behavior disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 3, 211223. Heins, T. (1996). Presenting rules to young children at school. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 21(2), 711. Kauffman, J. M., & Wong, K. L. H. (1991). Effective teachers of students with behavioral disorders: Are generic teaching skills enough? Behavioral Disorders, 16, 225237. Landrum, T. J., Tankersley, M., & Kauffman, J. M. (2003). What is special about special education for students with emotional or behavioral disorders? Journal of Special Education, 37, 148156.

Section 4 References Page 23 of 31

20 B E Y O N D B E H A V I O R

CREATING RULES FOR CLASSROOMS

Lewis, T. J., Hudson, S., Richter, M., & Johnson, N. (2004). Scientifically supported practices in emotional and behavioral disorders: A proposed approach and brief review of current practices. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 247259. Malone, B. G., Bonitz, D. A., & Rickett, M. M. (1998). Teacher perceptions of disruptive behavior: Maintaining instructional focus. Educational Horizons, 76(4), 189194. McGinnis, J. C., Frederick, B. P., & Edwards, R. (1995). Enhancing classroom management through proactive rules and procedures. Psychology in the Schools, 32, 220224. Murdick, N. L., & Petch-Hogan, B. (1996). Inclusive classroom management: Using preintervention strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 31, 172176. National Education Association. (2003). Meeting the challenges of recruitment and retention: A guidebook on promising strategies to recruit and retain qualified and diverse teachers. Internet site: http://www.nea.org/ teachershortage/images/rrg-full. pdf#search5%22Meeting%

20the%20challenges%20of% 20recruitment%20and%20retention% 3A%20A%20guidebook%20on% 20promising%20strategies%20to% 20recruit%20and%20retain% 20qualified%20and%20diverse% 20teachers.%22 (Accessed November 19, 2007). Rademacher, J. E., Callahan, K., & Pederson-Seelye, V. A. (1998). How do your classroom rules measure up? Guidelines for developing an effective rule management routine. Intervention in School and Clinic, 33, 284289. Ruhl, K. L., Hughes, C. A., & Camarata, S. M. (1992). Analysis of the expressive and receptive language characteristics of emotionally handicapped students served in public school settings. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders, 14, 165176. Shores, R. E., Gunter, P. L., & Jack, S. L. (1993). Classroom management strategies: Are they setting events for coercion? Behavioral Disorders, 18, 92102. Shores, R. E., Gunter, P. L., Denny, R. K., & Jack, S. L. (1993). Classroom

influences on aggressive and disruptive behaviors of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Focus on Exceptional Children, 26(2), 110. Shores, R. E., Jack, S. L., Gunter, P. L., & Ellis, D. N. (1993). Classroom interactions of children with behavior disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 1, 2739. Steinberg, Z., & Knitzer, J. (1992). Classrooms for emotionally and behaviorally disturbed students: Facing the challenge. Behavioral Disorders, 17, 145156. Stevenson, D. L. (1991). Deviant students as a collective resource in classroom control. Sociology of Education, 64, 127133. Sutherland, K. S., & Singh, N. N. (2004). Learned helplessness and students with emotional or behavioral disorders: Deprivation in the classroom. Behavioral Disorders, 29, 169181. Sutherland, K. S., & Wehby, J. H. (2001). The effect of self-evaluation of teaching behavior in classrooms for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Special Education, 35, 161171.

S PRING 2 0 0 8

21

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Classroom ManagementDocument24 pagesClassroom ManagementmightymarcPas encore d'évaluation

- Net Force WorksheetDocument3 pagesNet Force WorksheetMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies For Managing Disciplinary Problems Among Secondary Schools in Izzi Local Government AreaDocument100 pagesStrategies For Managing Disciplinary Problems Among Secondary Schools in Izzi Local Government AreaOpia Anthony100% (1)

- TOPIC 1 - Classroom Management - 2015Document23 pagesTOPIC 1 - Classroom Management - 2015Wan Amir Iskandar IsmadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Primary Reading Comprehension Strategies Rubric (2-3)Document3 pagesPrimary Reading Comprehension Strategies Rubric (2-3)Mary Child100% (1)

- Classroom DisciplineDocument146 pagesClassroom DisciplineMarilyn Lamigo Bristol100% (1)

- Business Enterprise SimulationDocument2 pagesBusiness Enterprise SimulationROSE MARY OTAZAPas encore d'évaluation

- How The World Works Parent Letter 15-16Document1 pageHow The World Works Parent Letter 15-16Y2NISTPas encore d'évaluation

- Task 1-Classroom Management TheoriesDocument10 pagesTask 1-Classroom Management TheoriesAfiq AfhamPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Management PaperDocument9 pagesClassroom Management PaperZaidah MYPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Math Grade 3Document42 pagesDLL Math Grade 3Mary Child100% (1)

- Ele 160 Remedial Instruction Syllabus AutosavedDocument6 pagesEle 160 Remedial Instruction Syllabus AutosavedRicky BustosPas encore d'évaluation

- Worksheet - Force Mass X GravityDocument2 pagesWorksheet - Force Mass X GravityMary Child100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines Region 02, Cagayan Valley: Department of Education Schools Division Office of Nueva VizcayaDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Region 02, Cagayan Valley: Department of Education Schools Division Office of Nueva VizcayaBernard GundranPas encore d'évaluation

- Practising Reflective WritingDocument26 pagesPractising Reflective WritingDaren Mansfield100% (1)

- Classroom Management TechniquesDocument80 pagesClassroom Management TechniquesReden UloPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Management and Dicipline PDFDocument15 pagesClassroom Management and Dicipline PDFNur Zahidah Raman100% (1)

- Discipline TheoriesDocument4 pagesDiscipline TheoriesTeacher Andri100% (2)

- Lesson Study Problem Solving Approach Masami I SodaDocument11 pagesLesson Study Problem Solving Approach Masami I SodaMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom ManagementDocument5 pagesClassroom ManagementFerrer BenedickPas encore d'évaluation

- Rheabrown Researchpaper FinalDocument48 pagesRheabrown Researchpaper Finalapi-309080527Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hass - Unit PlanDocument20 pagesHass - Unit Planapi-528175575100% (1)

- Effective Classroom ManagementDocument30 pagesEffective Classroom Managementrosetimah100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Math 7Document6 pagesLesson Plan Math 7Roy PizaPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Mother Tongue Grade 3Document42 pagesDLL Mother Tongue Grade 3Mary Child100% (3)

- RP 4 - Proportional Relationships Performance TaskDocument4 pagesRP 4 - Proportional Relationships Performance Taskapi-317511549Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter I: The Problem and It'S BackgroundDocument18 pagesChapter I: The Problem and It'S BackgroundMirafelPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument11 pagesResearch PaperCheska EsperanzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of School Rules and RegulaDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of School Rules and Regulanemigio dizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 2 Written AssignmentDocument7 pagesUnit 2 Written AssignmentKyaw MongPas encore d'évaluation

- Socdime Thesis FinalDocument60 pagesSocdime Thesis FinalGarlene Pearl GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Writing - Background of The Topic. Camile GiloDocument4 pagesThesis Writing - Background of The Topic. Camile GiloCamile GiloPas encore d'évaluation

- Fadipe Chapter 1-3Document26 pagesFadipe Chapter 1-3Atoba AbiodunPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1ClintPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 1,2,3 COMB. 5th and Final RevisionDocument38 pagesCHAPTER 1,2,3 COMB. 5th and Final RevisionMokong MakalinogPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Misbehavior: An Exploratory Study Based On Sri Lankan Secondary School Teachers' PerceptionsDocument11 pagesStudent Misbehavior: An Exploratory Study Based On Sri Lankan Secondary School Teachers' PerceptionsManisha ThakurPas encore d'évaluation

- Discipline Policies and Academic PerformanceDocument27 pagesDiscipline Policies and Academic PerformanceEly Boy AntofinaPas encore d'évaluation

- 5240 WA Unit 3Document7 pages5240 WA Unit 3KUNWAR JEE SINHAPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument10 pagesReview of Related LiteratureCleo LexveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Problematic Student BehaviorDocument3 pagesProblematic Student Behaviormashitiva100% (1)

- Problem PreventionDocument5 pagesProblem Preventionapi-285716610Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Fall - Plan For Supporting Positive BehaviourDocument7 pages2022 Fall - Plan For Supporting Positive Behaviourapi-639052417Pas encore d'évaluation

- In School SuspensionDocument8 pagesIn School Suspensionsharmila_kPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument2 pagesLiterature Reviews1094779Pas encore d'évaluation

- RESEARCH ORIGINAL (With Page)Document51 pagesRESEARCH ORIGINAL (With Page)Athena JuatPas encore d'évaluation

- Preparedness of Discipline in Secondary School in KenyaDocument16 pagesPreparedness of Discipline in Secondary School in KenyaMei MeiPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 1 - For MergeDocument4 pagesCHAPTER 1 - For Mergeクイーンクイーン ロペスPas encore d'évaluation

- Level of Awareness of The Grade 11 Abm Students On The Rules and Regulations of University of Cebu Lapu-Lapu and MandaueDocument17 pagesLevel of Awareness of The Grade 11 Abm Students On The Rules and Regulations of University of Cebu Lapu-Lapu and MandaueRon TablizoPas encore d'évaluation

- TEFL 8.classroom ManagementDocument5 pagesTEFL 8.classroom ManagementHadil BelbagraPas encore d'évaluation

- Pbis PaperDocument9 pagesPbis Paperapi-455214328Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1Document3 pagesChapter 1クイーンクイーン ロペスPas encore d'évaluation

- Case study-QUEZON CITYDocument11 pagesCase study-QUEZON CITYgelma furing lizalizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Action ResearchDocument17 pagesAction ResearchRae Jean BolañosPas encore d'évaluation

- Jeditor4,+Journal+Editor,+Simpson+ (2022)Document16 pagesJeditor4,+Journal+Editor,+Simpson+ (2022)JOSH CLARENCE QUIJANOPas encore d'évaluation

- McGuireetal 2023Document23 pagesMcGuireetal 2023Zainab RamzanPas encore d'évaluation

- MicyDocument14 pagesMicyMayo PerezIcyPas encore d'évaluation

- School Rules: How It Affects The Behavior of Students in La Consolacion University PhilippinesDocument13 pagesSchool Rules: How It Affects The Behavior of Students in La Consolacion University PhilippinesMyla Joy EstrellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Part A: Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesPart A: Literature Reviewapi-408524416Pas encore d'évaluation

- ThesisDocument20 pagesThesisDoris Day GutierrezPas encore d'évaluation

- Written Assignment Unit 3Document5 pagesWritten Assignment Unit 3Bicon MuvikoPas encore d'évaluation

- CoatesDocument5 pagesCoatesapi-371675716Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics in Educational Policy and ProceduresDocument32 pagesEthics in Educational Policy and Proceduresmaiden mendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- School Discipline: Its Impact As Perceived by The Basic Education LearnersDocument9 pagesSchool Discipline: Its Impact As Perceived by The Basic Education LearnersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Behaviour PlanDocument8 pagesBehaviour Planapi-491062836Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rules and Procedures For Positive Classroom EnvironmentDocument4 pagesRules and Procedures For Positive Classroom EnvironmentTeacher AndriPas encore d'évaluation

- DisciplineplanDocument11 pagesDisciplineplanapi-252396737Pas encore d'évaluation

- EDUC 5240creating Positive Classroom WA3Document6 pagesEDUC 5240creating Positive Classroom WA3PRINCESSAPas encore d'évaluation

- Statement of The ProblemDocument4 pagesStatement of The ProblemJirah GuillermoPas encore d'évaluation

- For PlagiarismDocument14 pagesFor PlagiarismNeuchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive 2h2018assessment1 EthansaisDocument8 pagesInclusive 2h2018assessment1 Ethansaisapi-357549157Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teachers' Strategies For Preventing and Stopping Young Learners' Misbehavior in English Classroom at Second Grade of Man 1 MakassarDocument8 pagesTeachers' Strategies For Preventing and Stopping Young Learners' Misbehavior in English Classroom at Second Grade of Man 1 MakassarSoviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1 and 2 ARDocument12 pagesChapter 1 and 2 ARkimahmin1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hal 1-2Document8 pagesHal 1-2nie_lamPas encore d'évaluation

- School's Role in Moulding DisciplineDocument7 pagesSchool's Role in Moulding DisciplineDarrelSinclairYengPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsD'EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Methods - Pros and ConsDocument7 pagesTeaching Methods - Pros and ConsMary Child100% (1)

- DLL EsP Grade 2Document42 pagesDLL EsP Grade 2Mary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Document9 pagesReading Comprehension Strategies For Elementary Students - Always A Teacher.Mary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaching All The Students in Your ClassroomDocument4 pagesReaching All The Students in Your ClassroomMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive Material For Measurement and EvaluationDocument54 pagesComprehensive Material For Measurement and EvaluationMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Seven Strategies To Teach Students Text Comprehension - Reading Topics A-Z - Reading RocketsDocument12 pagesSeven Strategies To Teach Students Text Comprehension - Reading Topics A-Z - Reading RocketsMary Child100% (1)

- Grades 1 2Document65 pagesGrades 1 2Mary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Teaching Strategies - Six Keys To Classroom Excellence - Faculty FocusDocument5 pagesEffective Teaching Strategies - Six Keys To Classroom Excellence - Faculty FocusMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- During Comp AaDocument26 pagesDuring Comp AaMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehension Strategies - Making Connections, Questioning, Inferring, Determining Importance, and MoreDocument10 pagesComprehension Strategies - Making Connections, Questioning, Inferring, Determining Importance, and MoreMary Child100% (1)

- The 1, 2, 3's and A, B, C's of Classroom ManagementDocument11 pagesThe 1, 2, 3's and A, B, C's of Classroom ManagementMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Management - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesClassroom Management - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Cmet Connecting Mathematics For Elementary Teachers Student SupplementDocument21 pagesCmet Connecting Mathematics For Elementary Teachers Student SupplementMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom Management: Cheryl Harvey, Secondary FacilitatorDocument13 pagesClassroom Management: Cheryl Harvey, Secondary FacilitatorMary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- Educator 101Document12 pagesEducator 101Mary ChildPas encore d'évaluation

- The Teaching Profession 1st SetDocument14 pagesThe Teaching Profession 1st SetMarla Grace Estanda AbdulganiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sentiment Analysis of Talaash Movie Reviews Using Text Mining ApproachDocument9 pagesSentiment Analysis of Talaash Movie Reviews Using Text Mining ApproachsudhvimalPas encore d'évaluation

- Çankaya University: IE 302 Facilities Design and Location Spring 2017Document2 pagesÇankaya University: IE 302 Facilities Design and Location Spring 2017santhosh kumar t mPas encore d'évaluation

- Journal Writing Week 10 Jurnal PraktikuDocument3 pagesJournal Writing Week 10 Jurnal PraktikuESWARY A/P VASUDEVAN MoePas encore d'évaluation

- Nicole Anderson - Inquiry - Te 808Document33 pagesNicole Anderson - Inquiry - Te 808api-523371519Pas encore d'évaluation

- NLC InsetDocument21 pagesNLC InsetAn NePas encore d'évaluation

- Course Instructions: European Business LawDocument4 pagesCourse Instructions: European Business Lawsaurovh mazumdarPas encore d'évaluation

- Full Download Essentials of Abnormal Psychology 8th Edition Durand Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Essentials of Abnormal Psychology 8th Edition Durand Test Bank PDF Full Chapteremergentsaadh90oa1100% (16)

- Assessing The Effect of Polya's Theory in Improving Problem - Solving Ability of Grade 11 Students in San Marcelino DistrictDocument10 pagesAssessing The Effect of Polya's Theory in Improving Problem - Solving Ability of Grade 11 Students in San Marcelino DistrictAJHSSR JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Final Na Ito 2Document42 pagesThesis Final Na Ito 2Angela RuedasPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid Year Evaluation 2022Document3 pagesMid Year Evaluation 2022api-375319204Pas encore d'évaluation

- CSC Week 4 6Document42 pagesCSC Week 4 6Diana Pecore FalcunitPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual O & A Commentary GuideDocument2 pagesIndividual O & A Commentary GuideCrystal EmmonsPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesLesson Plansam polgadasPas encore d'évaluation

- SRFDocument42 pagesSRFvkumar_345287Pas encore d'évaluation

- WAGGGS Educational Programme GuidelinesDocument57 pagesWAGGGS Educational Programme GuidelinesEuropak OnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Subject Content Knowledge Requirements PolicyDocument82 pagesSubject Content Knowledge Requirements Policyapi-570474444Pas encore d'évaluation

- TA PMCF Kinder GR 1 and Gr.2 TeachersDocument13 pagesTA PMCF Kinder GR 1 and Gr.2 TeachersVinCENtPas encore d'évaluation

- Forensic 6 Forensic BallisticsDocument4 pagesForensic 6 Forensic BallisticsrenjomarPas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Learning Plan - TEMPLATEDocument4 pagesDaily Learning Plan - TEMPLATEvlylefabellonPas encore d'évaluation

- Edma360 Assessment 3 Unit of WorkDocument7 pagesEdma360 Assessment 3 Unit of Workapi-300308392Pas encore d'évaluation

- Morales LeadershipDocument2 pagesMorales LeadershipJustin Jeric HerraduraPas encore d'évaluation