Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

2

Transféré par

calu balanCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

2

Transféré par

calu balanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

78 ISSN 02580802. LITERATRA2010 52 (3) PASIPHAEAND DAEDAlUSANDTHE FOUR PANElS OFTHE DOOR OF APOllOS TEmPlE (Vergil, aeneid 6.

2030) Prof. Horatio Caesar Roger vella Professor of the Department of Classics and Archeology, University of Malta Introduction It has been observed and widely agreed upon that Vergil composed his Aeneid with a structure, sometimes making symmetry even numerical1 . It has also been shown that to understand why Vergil wrote the poem, one must depart from and be guided by Vergils own structure. Studies of Vergils structure of the Aeneid have indeed received exhaustive scholarly attention2 . Particular attention has also been given to appreciating the symbolism behind the Aeneid by means of the observations made on the structure of the poem. The relationship between narrative structure and symbolism is sometimes given special focus by Vergil through ecphrasis3

. Much has already been said about this method of symbolically adverting the reader of what will take place, and what has taken place; and of the connexion between the past and the present both in the ecphrasis 1 On the existence ofsymmetry in Greek literature prior to Vergil,see H. Mac L.Currie (1976), 4647. 2 A.J.Boyle (1972a), 63. 3 While it is true that symbolism may be exaggerWhile it istrue thatsymbolism may be exaggerated, and connexions inferred where they do not exist, as pointed out by Th. E. Kinsey (1986), 137, there is a bigger danger of misinterpreting the Aeneid without symbolism. and between the ecphrasis and the poem or its message4 . Some of these ecphrases, precisely because they tend to introduce something important to come, are placed towards the beginning of a book. We are here immediately reminded of Odyssey VII, where Odysseus will meet Alcinous and Arete. Before Odysseus steps into the palace,

Homer pauses for a numerically perfectly structured passage describing the garden, and another numerically structured one similarly describing the entrance to the palace5 .Weunderstandwhatkindofpeople the Phaeacians were, remote from the rest of mankind, already from their horticultural and architectural activities, before we meet them. the openings of Aeneid I and VI On two occasions, right at the beginning of a book after a short introduction, Vergil presents us with such an ecphrasis. I refer to the Trojan reliefs on the Carthaginian battlements of Dido in Book I, and the Athenian andCretan ones on the door-pa4 H.C.R. Vella (2004). 5 H.C.R. Vella (1991), 148162.79 nels of the Temple of Apollo at Cumae6 . On both occasions, Vergil presents his hero as being absorbed in his study of the pictures. The reader will imagine the importance of pictures that could leave such

impressions on the hero he is following in the narrative. On both occasions, Aeneas is disturbed by the arrival of somebody, here a female character, Dido inBook I, and the Sibyl in Book VI.InBook I he had cried on seeing himself in pastsufferings; in Book VI Aeneas does not cry at seeing the sufferings of proles symbolised by the representations of analogous, foreign situations. Nor will he cry when he sees and picks up Vulcans Shield inBookVIII,wherein his proles are again represented in the midst of wars and battles7 . In all three ecphrases, therefore, is underlined the problem of suffering, as indeed in the whole of the Aeneid and the other major works of Vergil8 . Before he comes to Carthage, the wrong place, Aeneas vision of the real Promised Land had been blurred, and is very much attached to the seemingly never ending past; when 6 The story appeared in Catullus LXIV and in Ovids Metamorphoses VIII, for a discussion of which see B. Pavlock (19981999), 141157. It is also referred to by Vergils

contemporary, Horace, in his Odes (1.3, 2.20 and 4.2). For a discussion of treatment of the myth by otherClassical authors,see E. Paratore (1979), 208. For a discussion on the relationship of the temple of Apollo at Cumae to other temples of Apollo, see M. Paschalis (1986b), 4468. For a discussion of this ecphrasis in Vergil, see, for example, V. Poeschl (1975), 119123. 7 P. R. Doob (1990), 228, has already referred to this triptych involving Didos murals, Daedalus carvings and Vulcans Shield. 8 F. A. Sullivan (1969), 161177, but especially 161. Earlier, R. D. Williams(1964), 62, had referred to the equipoise of the Aeneid, that of success and failure, life and death, triumph and defeat, joy and sorrow. he comestoCumae9 , the place of initiation, Aeneas coming to Hesperia has materialized, and is now looking to what is next10 . It is in this context that Aeneas is absorbed by the metaphorical representations of his issue, atCumae in Hesperia11 . the Spectacula In general, the representations on the door

panels of the temple of Apollo may be said to represent aspects of Aeneas own past history. The symbolical relationship of Daedalus and Aeneas has already been aptly referred to by A.J.Boyle, who also agrees with the opinion that this ecphrasis has only four panels, as described below12. The last panel, however, may be said to represent not only his past, but also his imminent future.Thefirsttwo panelsdealwith death, suffering and sacrifice, and remind us of Creusa, Anchises, Dido and Palinurus13 . 9 For Vergils choice of Cumae in makingAeneas first landfall in Western Italy, see R.V. Schoder (1971 1972), 97109. For studies on Cumae and its relationship with Vergils narrative, see P.OR. Smiley (1948), 97103; R. J. Clark (1977a), 6371, and R. J. Clark (1977b), 482495. 10 In the words of H.C.Rutledge (19711972), 112, As Aeneas passes through the gates of the temple of Apollo we see him leaving his own dismal past behind him. He will not be the same person when he emerges from histotalCumaean experience. 11 In the words of M. C. J. Putnam (1998a), 244, with Daedalus artisanship Aeneas shares the element

of autobiography watching himself within an episode he views. See also M.C.J. Putnam (1987), 173174. 12 A. J. Boyle (1972), 116118. See also M. Owen Lee (1992), 8384, and 85, where he even compares Daedalus with Vergil, the author pitying Queen Dido and guiding Aeneas through the underworld. For a more negative view in the comparison of Daedalus with Aeneas, see J.W. Zarker (1967), 221: Daedalus, however, has no apparent relationship either to the rest of VI or the Aeneid as a whole. 13 M. Paschalis (1986a), 4041, sees the scene of Androgeus as heralding and trigering the scene of 80 In the third panel, Pasiphae reminds us of Dido, the notion of love and cruelty derived from the consequence of that love14. The fourth panel looks both back to Aeneas labyrinthine wanderings, and forward to his descent into the Underworld15 . The subject matter of this ecphrasis is therefore quite complex, comprising death (especially of the young)16, suffering, sacrifice, love (and cruelty resulting from it), and lifes wandering paths17. It is about life and its complexities, difficult to unravel and difficult to predict. As such, this ecphrasis is a microcosm of the whole Aeneid, where

progress is counterbalanced by loss of life18 . No doubt Aeneas was absorbed looking at the spectacula, not because they mirrored his past inspecificscenes,assomewouldinterpret19 , Marcellus at the end of VI and that of the death of Pallasin Book X. This, therefore, could not have been the reason why Aeneas tarried viewing such a scene, for Aeneas could not yet see the connection of Androgeus with his future, as sometimes hinted. 14 D. E. Eichholz (1968), 109, disagrees with Pschl(1962)in the comparison of Pasiphae with Dido. For further comparison of Pasiphae with Dido, see B. Otis(1964), 284,R.A. Hornsby 1970, 53,W. Fitzgerald (1984), 52 and D. Pike (1993). 15 See also W. Fitzgerald (1984), 52, and M. See also W. Fitzgerald (1984), 52, and M. Erdmann (1998), 500505. 16 See M. Paschalis (1986a), 3341, M. Paschalis (1986b), 64, and M.C.J. Putnam (1998b), 5. The ecphrasis, being in a way an introduction to the descent into the Underworld, warns Aeneas of immature deaths to be met in the Underworld, including those of Deiphobus and Dido. These young deaths ironically herald to Aeneas future ones of Pallas and Lausus in the second half of the Aeneid. 17 It is therefore much more than the grief for the death of Icarus and his feeling of guilt for the same Erd-

death, asin M. Paschalis(1986a), 35. 18 M.C.J. Putnam (1998b), 95. 19 M. Paschalis(1986a), 40, for example, mentions Icarus as reminding Aeneas of Palinurus, and so could not take off his eyes from the scene. But Vergil never included Icarus in the ecphrasis, and Aeneas could not have been detained by an Icarus-representation. orbecausetheywereGreekartisticrepresentations to be contrasted to Roman concepts of imperium20 , but because they reflectedMan and every viewer in a very deep way. These spectacula, therefore, were not trivial at all21 , even when compared to what the Sibyl and Anchises were going to show Aeneas in the Underworld. They were spectacula because they were graphic; at the same time, they were a forecast of what could be revealed to Aeneas in the Underworld, the destination as indicated by Anchisesin Book V. Even so, the real thing has still to come, and Aeneas must not tarry at these spectacula, as he will not tarry at meeting Palinurus and Deiphobus in the Underworld. Aeneas and daedalus BothDaedalus andAeneas are exiles22, and

both are devotees of Apollo.Both pay first 20 F. Zevi (1995), 187188. 21 Assaid byW.F.Jackson Knight (1969), 166. 22 A different view from that of R.J. Clark (1978), 150: Daedalus, an exile, is pictured here in order to be contrasted to Aeneas. The contrast lies in the fact that Daedalus escaped from his own labyrinth to end up carving his past on the doors of Apollos temple, whereas Aeneas escaped from Troy with hope of a future based on future generations. See also D. E. Echholz (1868), 111, andW. Fitzgerald (1984), 61. Forthe comparison ofAeneas with Daedalus as exiles, however, see, for example, V.Poeschl(1962),150,H.C.Rutledge(19711972),111, W.Fitzgerald (1984), 52,P.R.Doob (1990), 234, andM. Erdmann (1998), 488489. For the comparison of Daedalus and Aeneas as coming from the East with Augustus coming from Egypt, see H. C. Rutledge (1967), 310. Because of the comparison of Daedalus with Aeneas, it is therefore difficult to accept the comparison of Icarus withAeneas, asin H. C. Rutledge (19711972), 113. To the coming of Daedalus from the East, Sallust adds Sardinia as his preceding landfall,forwhich seeServius(ed. G. Thilo), 7: Daedalus vero primo Sardiniam, ut dicit Sallustius, post delatus est Cumas. For a comment on Vergils departure from tradition of making Daedalus come to Cumae from Sardinia, and not straight from Crete,see F. Zevi(1995), 178179.81 respects(pietas)toApollo,one for arriving

safely at Cumae by air, the other by sea23 . Like Daedalus, Aeneas escaped from his maze, labyrinthine Troy: Daedalus lost Icarus, Aeneas Creusa. As Aeneas in vain tried to embrace the ghost of Creusa,so in vain Daedalus tried to represent his son on the door panels(A.2.792793: ter conatus ibi collo dare bracchia circum; / ter frustra comprensa manus effugit imago) 24 . This ecphrasis, commonly referred to as Daedalus ecphrasis, is Vergils ecphrasis, just asthegardenandpalaceofAlcinous are Homers ecphrases. I say this because much has been said about the artist, Daedalus, as if he performed the work as described by Vergil! Whether the temple of Apollo existed or not, whether it was built by Daedalus or not25, it is still Vergil who is the artist here, and he has proved himself to be so great an artist, that some have even been tempted to give credit to Daedalus instead of to Vergil26!It isto the credit of Vergil that Daedalus is here seen to hit the mark, that ofbeingthefirst artistinClassicalliterature

to tell his own story in art27 . the ecphrasis in detail This ecphrasis occurs in Vergils Aeneid 23 M. Paschalis(1986b), 63. 24 B.Catto (1988), 73. 25 J. Perret (1978), 162, comments that Vergil was the first author who attributed the construction of the Temple of Apollo to Daedalus. 26 W. Fitzgerald (1984), 53,saysthat this ecphrasis is unique in that the artist(Daedalus)represents his own story. This story, however, is mythical, and not partly mythical and partly historical. Also, Daedalus was involved in the construction of the labyrinth, and in the affair of Pasiphae with the bull, but he was not involved in the death of Androgeus and the tribute paid by Athens toCrete. So it is not completely his own story. 27 M.C.J. Putnam (1998b), 5. VI28 , and it covers eleven lines from 20 to 30. It is preceded by six lines from 14 to 19, Daedalusflying29 fromCrete toCumae, and followed by four lines, from 31 to 34, giving us an explanation of why Icarus, who had died in the same flight, could not receive an artistic representation from his father30 .

These lines, altogether making up 21, come immediately after the Introduction to the poem,whose subjectmatterpreciselydeals with the coming ofAeneas and theTrojans to Cumae (13 ll.). They are then followed by 122 ll., a scene where Aeneas meets the Sibyl and is given instructions to perform the funeral of Misenus and to pluck the Golden Bough, itself a symbol of life and death, two conditions for him to start his descent into the Underworld31 . 1419 (6 ll.) Daedalus fliesfrom Crete to Cumae. 2030 (11 ll.) The ecphrasis on the temples gate 3134 (4 ll.) Why Icarus was not included in the ecphrasis. 28 B. Pavlock (19981999), 142, notes that Ovid too incorporated the story of Daedalus in the middle of his poem. 29 According to Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 79, DaeAccording to Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 79, Daedalus and Icarus did not fly, butsailed. He supportsthis view by referring remigium alarum to a maritime activity, for which he quoted also Vergil, A. 3.520: velorum pandimus alas. Although remigium refers to the sea, alarum can be said to refer to the air, and so the metaphor is pregnant both ways. Nevertheless, Servius

statement of Icarus death on voyage by sea would remind us more closely of the death of Palinurus. In any case, the ambiguity of the expression suits both Daedalus and Aeneas, both chased and exiled, Daedalus by Minos, Aeneas through Destiny. 30As observed by M.C.J. Putnam(1998b), 81, this part of the episode is a study in artistic incompletion that is extraordinarily complete as a poetic art. He even extends this notion of incompleteness to Aeneas failure fromhisideal by killingTurnus(95), a different concept from F.A. Sullivan (1959), 160: During the rest of the poem Aeneas never fails in his task. 31 SeeAlsoA.J.Boyle (1972), 136137.82 W. Fitzgerald remarks that this ecphrasis, when compared to the one of Didos muralsinBook I, comes up in the narrative abruptly, and that it is less motivated than the other. He even says that Aeneas is never directly represented observing the gates32 . Yet, as said above, Vergil here uses this ecphrasis as part of the introduction of Aeneas coming to Cumae. Furthermore, Aeneasis truly looking at the decorations; for how else could he be disturbed by Achates and the Sibyl and asked not to look at these spectacula (l.37)? We note from the above analysis that

Vergil dedicates practically as many lines to the coming (of Daedalus) and not coming (of Icarus) to Cumae asto the actual ecphrasis. Aeneas only sees representations on the door-panels (in the middle section, that is, the ecphrasis proper); he does not see the story of Icarus as we see it through Vergil. Vergil addresses Icarus who is not present for Aeneas to see, and in so doing make us see him all the same. And here our imagination runs forward: we imagine Daedalus trying to represent his sons tragic fall, but being unable. In any case, good thing he did not, for he would have spoiled the symmetry as we have it in Vergil, or as Aeneas sees it now: two pictures against two others, as follows: In foribus letum Androgeo33; // tum pendere poenas34 (6.20) 32 W. Fitzgerald (1984), 52. 33 For the genitive of Androgeo, see A. Di Prima (1960), 9396. 34 Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 5: quod Minos dolens collectis navibus bella commovit et victis Atheniensibus poenam hanc statuit. Note the alliteration of m in pendere poenas which recall A.7.595: ipsi has sacrilego pendetis sanguine poenas(for this echo and others,see

W. Moskalew (1982), 217). Cecropidae iussi // miserum septena35 quotannis36 corpora37 natorum38; //stat ductissortibus urna. Contra elata mari // respondet Gnosia tellus39: 35 The correct interpretation of septena as by seven, and not seven goes back centuries. See, for example, Servius(ed. G. Thilo), 6:septem de filiis et septem de filiabus; Ascensius (ed. Garland Publishing, Inc.), 324: septena: utriusque sexus septem, hoc est quatuordecim, corpora natorum, B.A. Gould ed. (1858), 441, and H.E.Burton ed.(1919), 362.Vergilfurther corroborates on the number offourteen (seven youths and seven maidens) by the sacrifice which the Sibyl performed, a sacrifice of seven sheep and seven bullocks. For the interpretation of septena as seven, however, see M. Paschalis(1986a), 35, M. Paschalis(1986b), 64, and M. OwenLee,(1992), 8292,who dedicatesthewhole article on the aspect of seven throughout the Aeneid. For the interpretation of corpora as corpses, see Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 9: bene corpora, quae adempta vita consumebantur. For the wrong inclusion of Theseus among the septena,see J.W. Zarker (1967), 222. 36 A metrical repetition of the previous line in the first four feet (dsds). Note also the trisyllabic words in miserum septena quotannis. See Servius(ed. G. Thilo), 6:singulis quibusque annis. Vergil here differs from the traditional nine-yearly tribute. 37 Note the alliteration of c and q in Cecropidae

quotannis / corpora. 38 Note the enjambement in the fi rst two succes- Note the enjambement in the first two successive lines of the ecphrasis. For the significance of septena, see note above. I suggest, contrary to the opinion of many commentators (e.g., Servius {ed. G. Thilo}, 9, G. Long ed. {1884}, 430), that (miserum!) should read simply miserum (syncopated form for miserorum), without the exclamation-mark. See also Ascensius (Garland Publishing), 324: liberorum, tam masculorum quam foemiellarum miserum, pro miserorum, hoc est miseratione dignorum. Hence one could note the double inner hyperbata (abcba)in miserum septena quotannis / corpora natorum. These last two words recall A.2.214: corpora natorum serpens amplexus uterque. Vergil does not refer to Theseus at all, not because he departs from the traditional story (as in M. Paschalis {1986a}, 35), but because he was here referring to the annual tribute Athens was paying to Crete. The voluntary or nonvoluntary enrolment of Theseus among the fourteen is outside Vergils story. 39 R.W. Cruttwell (1946), 85, aptly reminds us of Gnosia regna of 3.113 when we read Gnosia tellus, in the same way as Anchises laborem (6.892) would remind us of laborin l.27. Thus, Crete and Italy are connected through Aeneas ancestor Dardanus and through labyrinthine activities.83 hic crudelis amor // tauri40 suppostaque furto41 Pasiphae mixtumque genus // prolesque

biformis42 (6.25) Minotaurus inest, // Veneris43 monimenta44 nefandae; hic labor ille domus45 // et inextricabilis error46; 40 Transferred epithet. It is not love that is cruel, nor the bull for that matter. It is the result of that love which makes the existence of a monster cruel. However, for the interpretation of crudelis as signifying the cruelty of the deity who vindictively imposed this passion on Pasiphae, see M. Paschalis (1986a), 38, in which case one queries Vergils justice in placing Pasiphae in Tartarus. Servius in his Commentarii (ed. G. Thilo), 5, recounts on how Venus revenged herself against Pasiphae, the daughter of the Sun, for having her adulterous acts with Mars been reported by him to Vulcan: quod factum Venus vehementer dolens stirpem omnem Solis persequi infandis amoribus coepit. The story was also told by Homer in Odyssey VIII. 41 A metrical repetition of the previous line in the first four feet (sdss). Notice also the alliteration of c in hic crudelis. The supposta furto refers to Daedalus craft in building a wooden cow covered with hides to attract the bull, for which refer to Servius(ed. G. Thilo), 5, 10. 42 Note the chiasmus in a(que)bb(que)a in mixtumque genus prolesque biformis. Here occurs also a figure ofspeech (copia) whereby one thing is expressed differently twice. Not so for Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 10: mixtumque genus, secundum veritatem, prolesque

biformis, secundum fabulam. Also, Servius, 7 (et quia geminos peperit, unum de Minoe et alium de tauro, enixa esse Minotaurum dicitur, quod et ipse paulo post ostendit dicens mixtumque genus), interprets mixtumque genus not as monster, but in the fantastic myth of the two twins ofAlcmene,HeraclesfromZeus, and Iphicles fromAmphitryon.R.Armstrong (2002), 325,in her discussion of the Trojans departure from Crete, sees echoes in this passage with A.3.180181: agnovit prolem ambiguam geminosque parentis, / seque novo veterum deceptum errore locorum. 43 Veneris, a personified noun. On the subject of malicious love and its relationship to Pasiphae, see D. Pike (1993), 98103. 44 monimenta in the neuter plural to agree with various genders. 45 Note the antithesis of hicille . H.C.Rutledge (19711972), 111, applies labor and error with sensus pregnans to refer to the anguish caused to victims by the passion of Pasiphae. 46 Metrically inverse to the previousline in the first four feet (sddd/ddds). Note also the triple bisyllabic words in labor ille domus, and the assonance in et inextricabilis error. These last two words recall A.5.591: frangeret indeprensus et inremeabilis error. magnum reginae // sed enim miseratus amorem47 Daedalus ipse48 dolos // tecti ambagesque resolvit49

, caeca regens filo // vestigia50 . (6.30) The four pictures apparently are not clear to us all, even if Vergil made them so. In the first place, we should be agreed that there are four,notfive (orsix)pictures.Thedoor, presumably a double one, has four panels, two on each door. The opposition of the last two to the first onesis clearly given by Vergil by the word contra at the start of l.23, and by respondet Gnosia tellus in the same line. On one side is the Athenian situation, introduced by In foribus, involving a Cretan, Angrogeus51: the distinction between the first and the second of the Athenian pictures is indicated by tum, still half-way in the first line of the ecphrasis, within the fourth foot. On the otherside isthe Cretan situation involving an Athenian, Daedalus himself: the distinction here between the third and the fourth panel is indicated by sed, half-way through l.28, just after the penthemimeral caesura. Thus, on both pairs of panels, one Athenian and one Cretan52 , 47 Note the alliteration of m, and the hyperbaton in

magnum amorem. 48 Daedalus is in fact mentioned in the ecphrasis, contrary to whatW. Fitzgerald (1984), 53,said. 49 Metrically inverse and opposite to the previous line in the firstfourfeet(ssdd/ddss). Note also the triple bisyllabic words in ipse dolos tecti, and the hyperbaton in caeca vestigia. 50 Note the triple bisyllabic words in caeca regens filo. vestigia echoes A.5.592 (haud alio Teucrum nati vestigia cursu), as has been pointed out byR.Armstrong (2002), 335. 51 M. Paschalis (1986a), 36, compares the fate of Androgeus with that of Talon, murdered by the same Talon. One wonders whether the artist would have liked this comparison himself; but S. Casali (19951996), 1, compares the fate of Androgeus with that of Penthesilea on Didos muralsinBook I. 52 B. Otis(1964), 284, dividesthese panelsinto the84 there is a hero from the opposite side: Androgeus and Daedalus. Let us allow the ecphrasis to speak for itself, as Vergil reported it! Here we have four persons expressly mentioned: Androgeus,Pasiphae,Minotaur andDaedalus.We have no Theseus and Ariadne53, nor, in my opinion, were they meant to be included by Vergil, despite his knowledge of Catullus Peleus and Thetis and his use of it54. Of

these four personages, Androgeus occupies one panel, at the top ofthe left door(ifleft precedesthe right);Pasiphae andtheMinotaur occupy the panel at the top of the right door, while Daedalus occupies the fourth and last panel, at the bottom of the same right door. Cecropidae is not a person, but a people, and they occupy the only panel left, the bottom of the left door55. Daedalus representations are now complete, and the ecphrasis comes to the end here. Unfortunately, Vergils words ... quin protinus omnia / perlegerent oculis have been misunderstood to mean that Aeneas was prevented from reading to the end of the panels by the coming of Achates and the Sibyl56. Vergils words mean and verily Athenian (l.2022) and the Cretan (2330).The same does M. Erdmann (1998), 486487. 53 As interpreted by J. B. Greenough and G. L. Kit- Asinterpreted by J. B. Greenough and G. L. Kittredge eds. (1895), 364, J. W. Zarker (1967), 222, R.J.Clark (1978), 148: Sceneslaid inAttica andCrete evoking the figure of Theseus See also D. E. Eichholz (1968), 111, and P.R. Doob (1990), 230. 54 See especially Vergils imitation of Catullus abandonment of Ariadne on the shores of Naxos when he was portraying Aeneas withdrawal from the shores

of Dido, for which discussion see D. H. Abel (1962), 5758. 55 The division of the representations on the door of Apollo into four panels as described here in fact goes back to centuries.See,for example,J.B.Greenough and G. L. Kittredge eds. (1895), 364. 56 R.Armstrong (2002), 337: Aeneasreading, we they would have scanned with their eyes everything forthwith. Vergil here wants to hint, as in the case of the spectators reaction to Didos murals and Vulcans Shield, that Aeneas and the Trojans were so absorbed by what they saw, that they needed more time to dwell thoroughly on every detail (omnia perlegerent). The representations were those which we read, and no message, like that of the secret of life and death, was missed. the third and fourth panels I come now to some mistaken views related to the third and fourth panels, if not also on the so-called fifth orsixth panels. I start by quoting again the very important line in this controversy: Magnum reginae sed enim miseratus amorem In the fourth panel, Vergil says, Pasiphae is in the labyrinth. To understand this statement, we have to review the third panel

taken together: contra elata mari respondet Gnosia tellus: hic crudelis amor tauri suppostaque furto Pasiphae mixtumque genus prolesque biformis Minotaurus inest, Veneris monimenta nefandae57; hic labor ille domus et inextricabilis error. Thefirstline, aswe saidearlier,startsthe Cretan picture, which simply talks of the labyrinth (labor), in which are to be found (inest)Pasiphae andtheMinotaur.Theverb inest is in the singular by attraction to its are told, was not yet complete ... he (the spectator) does not even see every panel of the temple doors. For similar views,seeW. Fitzgerald (1984), 53. 57 Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 10: aut memoria turpissimi coitus, aut ultio Veneris a Sole proditae, significat autem Minotaurum.85 nearestsubject, that is, Minotaurus.But the subjectis various: crudelis amor, Pasiphae, and Minotaurus, who has, as appositions preceding him, mixtumque genus and proles biformis. The labyrinth, constructed by Daedalus according to legend, contains the sin ofPasiphae (crudelis amor),the sinner(Pasiphae), her manner ofsinning (furto), and the result of her sin, Minotaurus, a monster58 .

This interpretation of Daedalus labyrinth is important, as it anticipates the contents of both monsters and sins to be met in Vergils own labyrinth, that is, the Underworld. In Latin, we are aware of the distinction between hic , ille to mean here , there .Thiswedonothavehere.Instead we have hic , hic In other words, we have one and the same thing: the labyrinth at Crete and what it contains, Pasiphae and the Minotaur. Vergil, therefore, does not make Daedalus add another separate panel, that is, the labyrinth. The two hics do not mean the same here: the first is a particle of reference (here), the other a demonstrative pronoun in the masculine gender to agree with labor. Ille signifiesthe famous labyrinth, the well known one in Crete. Here it is, Vergil isimplying, thisis what contains Pasiphae and the Minotaur, making up this frame59 . 58 And not just the Minotaur, as in M. Paschalis (1986a), 38. More on the various use of the word labor by Vergil in the Aeneid,see P.R. Doob (1990), 229. Furthermore, Doob (230) compares many items of the description of the labyrinth here with those referring to

the Trojan horse in Aeneid II. P. A. Miller (1995), 229, compares the unlawfulness of Pasiphae in this ecphrasis with the unlawfulness of the Trojan women burning their ships and Ascanius riding Didos horse in AeneidV. In his words, the labyrinth contains the Minotaur, the product of Pasiphaes bestial lust (232). 59 Indeed, this picture of the labyrinth, compris- Indeed, this picture of the labyrinth, comprising both Pasiphae and her son the Minotaur, is given Here lies inside the cruel love of the bull, and Pasiphae, having been placed under(him) by a trick, and the Minotaur, the mixed race and the two-shaped offspring, monuments of horrible love: this is the famous labyrinth and the inextricable maze. The symbolism, then, becomes clear: the Underworld, a labyrinth, is the place where one should find sins, sinners, and monsters, apart from other things which will be described in the rest of the Book VI. Furthermore, the Underworld-episode unites and summarizes the first six books of the Aeneid, the inextricabilis error Aeneas bids farewell to and completes60, and heralds what is to come by way of Aeneas intrigues in Latium61 . Regina Pasiphae We come now to the identification of regina.

magnum reginae sed enim miseratus amorem Daedalus ipse dolos tecti ambagesque resolvit, caeca regens filo vestigia. The verb is resolvit, its subject is Daedalus, with whom agree the past participle miseratus before, and the present participle regens after. reginae does not refer to Ariadne62 (who was not a queen), but to Pasipmore lines by Vergil than that of the Athenian youths (M. Paschalis {1986a}, 39). Apart from the more cruel fate that the Minotaur receives, it was for him that Daedalus was asked to construct the labyrinth initially, later on to receive the human tribute from Athens. A different interpretation of hic ... hic as introducing two separate frames, and not one and the same frame, was given by J.W. Zarker (1867), 221. 60 See alsoB.Otis(1964), 284, andB.Catto (1988), 76. 61 H.C.Rutledge (19711972), 113. 62 As in Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 10, B. A. Gould (1858), 441, J. W. Zarker (1967), 222, W. Fitzgerald (1984), 54, Th. E. Kinsey (1986), 137, M. Paschalis86 hae herself. Apparently,B. Otisisthe only critic who anticipates my view that the pity Daedalus shows is indeed for Pasiphae63 . As such, therefore, he receives the criticism of M. Paschalis who says that the reunion

of mother and son strikes a discordant note in a series oftragic deaths.But did Vergil want to talk only on tragic deaths? Does not the Minotaur reflect a tragic death understood from the myth not described in this ecphrasis? Also, weak is Paschalis reason for taking regina to mean Ariadne and not Pasiphae, namely, because Ariadne is not mentioned at all, so she it must be here, while Pasiphae appears again later on in Aeneid VI and in E. 6.4560, and so does not need to come in here as well!64 And why should Daedalus have pitied Ariadne at thisstage (he would have pitied her abandoned at Naxos), for her great love for Theseus, who is also neither mentionednorindicatedhere? Whyshould Daedalus be involved with her? It was not Daedalus that rescued Theseus by the thread (filo) 65, but Ariadne, and that story was still to come, outside the ecphrasis. The idea that a princess(not queen) helping a future husband by a trick and betraying her father and fatherland, to be later on abandoned by that man, is a recurrenttheme inGreekmythology.Medea, Ariadnes cousin, for example, helped Jason

by her magic to lull to sleep the monster, guardian ofthe goldenfleece.In so doing,she betrayedAeetes and escaped fromColchis, (1986a), 35,M.C.J.Putnam(1987), 175, 179,M.Owen Lee (1992), 84, and S.Casali (19951996), 1. 63 B. Otis(1964), 284. 64 M. Paschalis(1986a), 37. 65 As interpreted by J. W. Zarker (1967), 222, and M. Paschalis(1986a), 35. only to be abandoned by Jason at Corinth. But the story of Theseus and Ariadne does not come in Vergils ecphrasis, and it is not necessary to say that these two figures were pushed to the background, with their names not even mentioned66 . Meanwhile, Daedalus, who pitied the great love Pasiphae, the queen, had, not for the bull here, for that has been mentioned earlierinthe ecphrasis(crudelis amor), and for which love he himself was involved by the settingupofthefictitious cow(furto) 67 , but for Minotaur, her son, wants to rescue her himself(ipse).Why ipse? From remorse, as just said, but also because he knew

the way to the labyrinth since he himself constructed it to retain her offspring, the Minotaur68. Vergil here is either quoting a source unknown to us, or is supposing a detail in the life of Pasiphae: he rescues the queen in a visit she makes to her offspring, the Minotaur, a task not to be dared, not because of the Minotaur, her son, but of finding her way out. Daedalus, therefore, helpsherbythe threadtofindthe exitofthe labyrinth. In so doing, he foreshadows also the Sibyl, who will guide Aeneas both into and out of the labyrinthine Underworld69 . 66 M. Paschalis (1986a), 35. See also J.W. Zarker (1967), 222, before him, where he states lest itsuggest to Aeneas or to the reader the kind reception of Aeneas by Dido and as that of Theseus by Ariadne and the subsequent seduction and ungrateful abandonment of both Dodo and Ariadne. 67 And so was truly involved in the affair of Pasiphae, contrary to what W. Fitzgerald (1984), 54, said: Daedalus own part in the story of Pasiphae is not mentioned.For a comparison ofthe cowand theTrojan horse,see M.C.J. Putnam (1998b), 84. 68 And so is truly mentioned as creating the laby- And so is truly mentioned as creating the labyrinth, not asinW. Fitzgerald (1984), 54.

69 In the words of P.R. Doob (1990), 56, there is also a labyrinth with a happy ending ... carefully shaped by a master architect to direct the worthy wanderer to a profitable end.87 The idea of the thread, no doubt, Ariadne, later on, learnt to use for her future husband, alterum Iasonem, when he goes in to kill the Minotaur and rescue the fate of the sixyouths(andhimself) andsevenmaidens. But the thread was used here by Daedalus himself: he who made the labyrinth, he who helped Pasiphae commit the sin, he himself now solved the problem of going in and out off the labyrinth to let her see her offspring once more (ipse resolvit). Symbolically, this means that the divine, who made heaven and earth, will itself guide us through the exit by divine means. Daedalus used the filum, Aeneas will use the GoldenBough (species auri frondentis opaca) as indicated by the Sibyl. Aeneas is ipse divine: he will make it to the exit of the Underworld, having shown admiration attheoffspring(proles)thatwerewaitingto beborn(hencebiformis in the sense of being ex-Trojan and future Roman), as shown by Anchises, and pity (miseratus) towards

Palinurus, Deiphobus and Dido. Icarus Icarus70 is not part of the picture. In fact, Daedalus twice tried to put him in, and twice he failed. This does not render Daedalus work, and our ecphrasis, incomplete. M.T. Bahr-Volkevenseesthisincompleteness as a symbolism of Vergils own incompleteness of his own poem71 , or, as A.J. Boyle 70 Servius (ed. G. Thilo), 7: Icarus altiora petens, pennis solis calore resolutis, mari in quod cecidit nomen Icarium inposuit. 71 M. T. Bahr-Volk (19741975), 16: but was himself (Daedalus) unable to complete the bas-relief because of sorrow for his lost son. ... Vergil may be implying that his own poemcan be only a partialreflection of the reality he recognizes as true and complete. said, Aeneas prospective failure within the poem72 , or as H.C. Rutledge said earlier, Daedalus himself could not prevent the death of Icarus, Aeneas Pallas73 .ButIcarus is there all the same, represented through a different art, epic. Vergil succeeded to complete in poetry what Daedalus failed to do in art74

.We see Icarusstory just asifit formed another panel75; but it does not! Had Daedalus succeeded, where would he have placed Icarus, in the next (fifth) panel76?! Aeneas sees nothing, but is able to imagine, as Vergil, the author, speaks his thought out, that the four panels would not be so arranged had Daedalus included the story of Icarus. tu quoque magnam (6.30) partem opere in tanto, // sineret dolor, Icare, haberes. Bis conatus erat // casus effingere in auro,77 bis78 patriae cecidere manus.79 // Marcellus and Icarus, and Vergils missing apodosis Icarus in Aeneid VI represents the death of a young man who, like Palinurus, becomes a victim for his countrymen80. Icarus contri72 A.J.Boyle (1972), 118. 73 H.C.Rutledge (1967), 310. 74 M.C.J. Putnam (1987), 181182. 75 S.Bartsch (1998), 336. 76 The idea that Daedalus constructed five panels was in fact suggested by M. Paschalis (1986b), 64, M.C.J.Putnam(1987),175, andM.C.J.Putnam(1998b),

77. 77 Metrically opposite to the previous line in the first four feet (dsdd/sdss). Note also the assonance in effingere in auro. 78 Note the anaphora of bis in these two lines. 79 Note the play on the words casus / manus, both of the fourth declension and bisyllabic, one after, the other before the caesura. 80 See also M. Paschalis(1986a), 40.88 buted to mans inventions. His death serves as a lesson for man to know his limits, and to explore safe navigation. Like Icarus, the seven young men and seven girls died for Athens as tribute to Crete. They paid for mans arrogance, as shown here towards Androgeus. Like Icarus, Marcellus, this time at the opposite end of the book, will die as a victim to disease, mans failure to combat. Man learns of his weakness in the midst of his advancement. As the sad memory of Icarus mars Daedalus successful attempt to incorporate him within his artistic door-panels, so does the sad inclusion of Marcellus mar the effect derived from the pageant of successful heroes still to be born81. Vergil thus hints here at mans sorrows, at his inability to cope with tragedies, and at mans failure to

understand Gods Mind and Destiny82. This is the role of Aeneas as a religious hero in a religious poem83 . Man diesto be born again. But whether Icarus will be Marcellus a thousand years after, is an open question84 . We have seen Daedalus being compared to Aeneas. Icarus is Daedalus son, Marcellus is Aeneas, both as offspring of his descendants, and as the 81 And Augustus pleasure in listening to Vergils recital of this passage. See also R. D. Williams (1964), 62. 82 See also W.A. Camps (19671968), 30, A.J. Boyle (1972), 124, W. Fitzgerald (1984), 52, and M. Paschalis(1986a), 35. 83 F.A. Sullivan (1959), 150: A religious hero is a man who senses, beyond earthly things, a Being or Power on whom he depends, to whom he is bound, and without whom he feels lonely and afraid in the world. 84 On the comparison of Marcellus with Julus or Icarus, see M. Owen Lee (1992), 8790. On the significance of forgetting the past for Aeneas and the Roman administration, and of their failure to learn from experience because of amnesia, see A.J. Boyle (1972),

126129, and 141. adopted son of Augustus represented by himself in the poem. Anchises, at the other end oftheBook, addresses a soulstill to be born, and tells him, tu Marcellus eris. ... As Vergil addresses Icarus at the beginning ofthebook(3031), ...tu quoque magnam / partem opere in tanto, sineret dolor, Icare, haberes, so does Anchises address Marcellus atthe endofthebook(882 883).Inboth addresses, Vergil includes a hypothetical conditional clause (sineret dolor; si qua fata aspere rumpas). In the first part, the apodosis is magnam partem haberes, in the second part, the apodosis is missing, for tu Marcellus eris in the indicative is another sentence85. The missing apodosis would be to the effect of Achises saying, tu Icarus sis. As things turned out to be, Achises halted fromfinishing the apodosis, asif not to reveal such deep secrets, and abruptly and dramatically moved on to a new sentence (tu Marcellus eris). A confirmation of this transmigration of souls can be the next word (... manibus date lilia plenis). Vergil here was comparing this scene with the Icarus scene, where he has said, bis

patriae cecidere manus. .... The hands of Daedalus fell, not so will those of Aeneas in bestowing lilies on to Marcellus. the sixth panel?! Apart from the story of Icarus which Daedalus did not represent, but was imagined by Aeneas, S. Casalisuggeststhat Aeneas could have time to see yet another panel (in his imagination, not that of Aeneas!), 85 Only one scholar,D.T. ShackletonBailey (1986), 199205, quoting Rolfe Humphries, a 1951American poet and translator, has come to the conclusion that this apodosis is missing.89 that of Theseus and Ariadne, if he had not been interrupted by Achates and the Sibyl. If this imagined panel were to be accepted as really occurring to the mind of Daedalus and, therefore, Vergil, it would be the sixth panel86 , following the fifth of Icarus. But this was not so, for we must distinguish fact(four panels)fromDaedalusintention (Icarus), and still from fantasy (Theseus and Ariadne). Casali supports this view by making us compare the experience of Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus at Naxos, with

that of Dido, abandoned by Aeneas87 . But Ariadne did not commit suicide, nor did Aeneas leave Dido for negligence. He also wants us to be aware that amor is repeated eight times in Aeneid IV, as it appears here once in magnum amorem(l.28), andthat regina should remind us of Dido, to whom the word refers 21 times in the Aeneid88 . Unfortunately, the number of times a word is repeated does not necessarily indicate the person concerned the next time we meet with that word! theseus and Ariadne Finally, the comparison of Aeneas and Theseus is also unfortunate89, since Aeneas did 86 M. Owen Lee (1992), 85, even goes further to say that the destructive passion of the Cretan queen (Ariadne) is a figure for Dido, echoing H.C. Rutledge (19711972), 111112. Rutledge continues to compare this passion with that which caused the Trojan War and the flight ofAeneas hither. 87 See also D.H.Abel (1962), 5761. 88 D. Pike (1993), 99, although doubting whether regina refers to Pasiphae, still compares with Dido not Ariadne, but Pasiphae.

89 J.W. Zarker (1967), 220226, begins and conJ.W. Zarker (1967), 220226, begins and concludes his article by hinting at this unfortunate comparison (which he does not deny to exist), as follows: In VI, however, Vergil progressively reveals the less attracnot end up in Tartarus, nor did he abduct or run away with Dido90. To me, his absence does not invoke his presence91. In fact, neither Theseus nor Minos are mentioned in the ecphrasis, even if these two personages appear together with the urn and Pasiphae in Tartarus92. It is therefore unnecessary to state that Theseus is the unifying factor in these panels93 . Similarly, Vergils familiarity with Homers description of Achilles Shield and its reference to Ariadnes Cretan dance (Il.18.590606)94 did not have to condition him to reserve a place for Ariadne in Daedalus carvings. Cruttwell even suggests that Theseus and Ariadne must be imagined within this ecphrasis to have dancedwith the rescued 14 (thatis, himself included)95 . Colours, metals and centrepieces An ecphrasis is normally related to colours and metals used, as in the case of the description of Shields96. Our ecphrasis

does not mention metals and colours. However, we understand that bronze was the metal, and that gold was used to gild it97. In fact, both before and after the ecphrasis, Vergil refers to the aurea tecta (l.13), that is, the tive qualities of the Athenian hero. ... Vergil seems to be saying that the epic hero Theseus is no longer suitable in the world of Augustan Rome. 90 S.Casali(19951996), 38. See also J.W. Zarker (1967), 222, and M. Owen Lee (1992), 85. 91 AsinR.J.Clark (1978), 150. 92 A comparison and conclusion drawn by R. W. Cruttwell (1946), 84. 93 M. Paschalis(1986a), 34. 94 For which see S.H. Lonsdale (1995), 273284. 95 AsinR.W.Cruttwell (1946), 89. 96 H.C.R. Vella (2005), 5787. 97 Rather than as the material of construction, as in M. Paschalis(1986b), 63.90 temple of Apollo, and to Daedalus attempt to represent Icarus in auro(l.32).A.J.Boyle comments on the importance Vergil gives to the element of goldenness, and its relationship to failure, death and nonfulfilment as we encounter the Golden Bough, the golden promises of history (6.793ff.) and

the golden Shield98 . An ecphrasis also has normally a centrepiece, especially when it covers the description of Shields99. Our ecphrasis with four panels,madeupofhalfAthenian,halfCretan pictures, may be said to have central undercurrent themes asmentioned above; but the structure of the doors do not allow them to be presented with centrepieces as in Shields. Even Jasons mantles centre in Apollonius Argonauticon has no pictorial detail100 . 98 A.J.Boyle (1972), 119. 99 R. F. Thomas(1983), 175184. 100R. F. Thomas(1983), 177. Conclusion Daedalus representations are divided into four panels,twoAthenian, and twoCretan, involving, in each panel, Androgeus, the Cecropidae, Pasiphae and the Minotaur, and Daedalus. As such, they exclude Icarus, Ariadne and Theseus. The third and fourth panels represent Cretes labyrinth, where Daedalus helps Pasiphae visit her offspring, the Minotaur, and come back alive from the labyrinth. These representations are not trivial(spectacula), but artistic representations (spectacula) of deep and

important events in human experience. They usher Aeneas and the reader into the labyrinth of the Underworld, with similar undertones ofsuffering, where he finally comesto the pageant of heroes, including Icarus, to be bornagainasMarcellus,justbeforeAeneas is guided safely by the Sibyl into the world of the living. BIBlIogRAPHy Abel, D. H., 1962: Ariadne and Dido, C.B. 38: 5761. Armstrong,R., 2002: Crete in theAeneid: recurrent trauma and alternative fate, C.Q. 52 (1) N.S.: 321340. Bahr-Volk, M. T., 19741975: Reality and nonreality in book six of the Aeneid, P.V.S. 14: 1618. Bartsch,S. 1998: Ars and the man: the politics of art in Virgils Aeneid, C.Ph. 93 (4): 322342. Boyle, A.J., 1972a: The meaning ofthe Aeneid. A critical inquiry, I: Empire and the individual. An examination of the Aeneids major theme, Ramus 1: 6390. Boyle, A.J., 1972b: Themeaning oftheAeneid. A critical inquiry, II: Homo immemor. Book VI and itsthematic ramifications, Ramus 1: 113151. Burton, H. E., 1919: Commentary on Vergil, Aeneid,Boston: Silver,Burdett

andCompany. Camps,W. A., 19671968: The role ofthe sixth book in the Aeneid, P.V.S. 7: 2230. Casali, S., 19951996: Aeneas and the doors of the temple of Apollo, C.J. 91 (1): 19. Catto,B.,1988.ThelabyrinthontheCumaeangates and Aeneas escape from Troy, Vergilius 34: 7176. Clark, R. J., 1977a. Misenus and the Cumaean landfall. Originality in Vergils use of topography and tradition, T.A.Ph.A. 107: 6371. Clark,R.J.,1977b: Vergil,Aeneid6.40ff. andthe Cumaean Sibyls cave, Latomus 36: 482495. Clark,R.J., 1978:Catabasis. Vergil and the wisdom tradition, Amsterdam: Grner. Cruttwell, R. W., 1946: Virgils mind at work. An analysis of the symbolism of the Aeneid, Oxford: Blackwell. Currie, H. MacL., 1976: Symmetry, poetry and geography, C.B. 52: 4647. Di Prima,A., 1960: Le forme di genitivoAndrogeo e simili in Virgilio, Paideia 15: 9396. Doob, P. R., 1990: The idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages, Ithaca, New York:Cornell University Press.91 Eichholz,D.E.,1968: Symbol andcontrastinthe Aeneid, G.&R. 15: 105112. Erdmann, M., 1998: Die Bilder am Apollotempel von Cumae und ihre

Bedeutung im Kontext der Aeneis, Gymnasium 105 (6): 481506. Fitzgerald, W., 1984: Aeneas, Daedalus and the labyrinth, Arethusa 17: 5165. Garland Publishing, Inc., ed. (year not given). Ascensius, New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. Greenough,J.B. andKittredge,G.L., eds., 1895: Publius Vergilius Maro, Bucolica, Aeneis, Georgica, Boston and London: Ginn andCompany. Gould,B. A., ed., 1858: Vergil, Aeneid, Sanborn: CarterBazin andCompany. Hornsby, R. A., 1970: Patterns of action in the Aeneid. An interpretation of Vergils epic similes, IowaCity: Iowa University Press. Jackson Knight, W.F., 1969: Virgils Elysium, in: Virgil, ed. D. R. Dudley, London: Kegan Paul1, 61175. Kinsey, Th. E., 1986: Pictures on temple doors. Aeneid 6.941, L.C.M. 11: 137. Long., G., ed., 1884. Vergil, Aeneid, London: Whittaker. Lonsdale, S. H., 1995: A dancing floorfor Ariadne (Il. 18.590592): aspects of ritual movement in Homer and Minoan religion, in: The ages of Homer: a tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule, eds.J.B.Carter andS.P.Morris,Austin (Texas):UniversityofTexas Press, 273284.

Miller,P.A.1995: TheMinotaurwithin:fire,the labyrinth, and strategies of containment in Aeneid 5 and 6,C.Ph. 90 (3): 225240. Moskalew, W., 1982: Formular language and poetic design in the Aeneid. Mnemosyne Supplement 73, Leiden:Brill. Otis, B., 1964: Virgil. A study in civilized poetry, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Owen Lee, M., 1992: Seven suffering heroines and seven surrogate sons: the two worlds of the poet: new perspectives on Vergil, in: Classical Studies Pedagogy Series, eds. R. M. Wilhelm and H.Jones, Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 8292. Paratore,E., ed.,1979:Vergilio, Eneide, Fondazione Lorenzo Valla, Arnaldo Mondadori Editore. Paschalis,M., 1986a: The unifying theme ofDaedalussculptures on the temple of ApolloCumanus (Aen. 6.2033), Vergilius 32: 3341. Paschalis, M., 1986b: Virgil and the Delphic oracle, Philologus 130: 4468. Pavlock, B., 19981999: Daedalus in Ovids Metamorphoses, C.W. 92 (2): 141157. Perret,J., ed.,1978:Virgile, nide Livres VVIII, Paris: Socit dditions LesBelles Lettres. Pike, D., 1993: Venus nefanda: Dido and Pasiphae in Vergils Aeneid, Akroterion 38: 98103.

Poeschl, V., 1962: The art of Vergil. Image and symbol in the Aeneid. (Tr. G. Seligson), Michigan: Ann Arbor University of Michigan Press. Poeschl,V., 1975: DieTempeltren desDdalus in der Aeneis(VI 1433), W.J.A., N.F. 1: 119123. Putnam,M.C.J., 1987: Daedalus,Virgil and the end of art, A.J.Ph. 108: 173198. Putnam, M. C. J., 1998a: Didos murals and Virgilian ekphrasis, H.S.Ph. 98: 243275. Putnam, M. C. J., 1998b: Vergils epic designs: ekphrasis in the Aeneid, New Haven (Conn.): Yale University Press. Rutledge, H. C., 1967: Vergils Daedalus, C.J. 62: 309311. Rutledge, H. C., 19711972: The opening of Aeneid 6,C.J. 67: 110115. Schoder, R. V., 19711972: Vergils poetic use of theCumae area,C.J. 67: 97109. Shackleton Bailey, D. T., 1986: Tu Marcellus eris, H.S.Ph. 90: 199205. Smiley, P. OR., 1948: In the steps of Aeneas, Greece and Rome 17: 97103. Sullivan, F. A., 1959: The spiritual itinerary of Virgils Aeneas, A.J.Ph. 80: 150161. Sullivan, F. A., 1969: Virgil and the mystery of suffering, A.J.Ph. 90: 161177.

Thilo, G., ed. Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii Aeneidos libros VVIII Commentarii, Lipzig: Teubner. Thomas,R. F., 1983: Virgils ekphrastic centrepieces H.S.C.Ph. 87: 175184. Vella, H. C. R., 1991: Some novel aspects in Homers Odyssey and Longus, Studi italiani di filologia classica 9, 2: 148162. Vella, H. C. R., 2004: Vergils Aeneid and the Shield of Aeneas: recurrent topics and cyclic structures, Studia humaniora Tartuensia, v, A, 1.(www. ut.ee/klassik/sht/ Vella, H.C.R., 2005: Four ecphrases: Virgil indebted to whom?, in: Antiquitas viva: studia classica, eds. O. Lams et al. 2, 5787, Latvia: Zinatne. Williams, R. D., 1964: The sixth book of the Aeneid, Greece and Rome 11: 4863. Zarker, J. W., 1967: Aeneas and Theseus in Aeneid VI, C.J. 62: 220226. Zevi, F., 1995. Gli Eubei a Cuma: Dedalo e lEneide, R.F.I.C. 123: 178192.92 PAsIFAJ, dEdAlAs IR KEtuRI APoloNo VENtyKlos RElJEFAI (VERgIlIJus, ENEiDa 6. 2030) Horatio Caesar Rodger Vella Santrauka VergilijausEneidosstruktrayragrieta irsimetrika, kartaisnetmatematikaitiksli.Btentgrieta simetrin kompozicija leidia velgti simbolin apraom

dalyk turin. Pasakojimo struktros ir simboli lygmensssajosypa akivaizdiosgiesmipradioje esaniose ekfrazse.Jos daniausiai yra tarsi vadas giesms turin. Vienu metu apibendrindamos tai, kas yra vyk, ir tai, kas turi vykti, tokios ekfrazs gauna simbolin prasm ir yra vienas i poemos idjini akcent. Grieta simetrija sudliotos eiluts parodo, kad Eneidos etosios giesms pradioje esanti ekfraz (6. 2030), viena vertus, yra tarsi vadas bsimas Enjo klajones po mirusij pasaulio labirintus. Kita vertus, joje aprayti keturi Apolono ventyklos dur reljefai prasmina ir Enjo praeit ir jo laukiani ateit.Juose atsispindi mirtisir kania, auka irmeil; taigi tuo patmetu reljefai apibendrina bendr mogikj patirt. Gauta 2010 09 30 Priimta spaudai 2010 12 06 Autoriaus adresas: Department ofClassics and Archeology University of Malta, MSD 06 Msida, Malta El. patas: horatio.vella@um.edu.mt

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Heroic Temper: Studies in Sophoclean TragedyD'EverandThe Heroic Temper: Studies in Sophoclean TragedyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (4)

- Casali - 2006 - The Making of The Shield Inspiration and RepressiDocument20 pagesCasali - 2006 - The Making of The Shield Inspiration and RepressiphilodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- Antigone: "One word frees us of all the weight and pain in life. That word is love"D'EverandAntigone: "One word frees us of all the weight and pain in life. That word is love"Pas encore d'évaluation

- Omnia Mutantur, Nihil Interit?Document2 pagesOmnia Mutantur, Nihil Interit?StarlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Segal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Document27 pagesSegal, Kleos and Its Ironies in The Odyssey.Claudio CastellettiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pelliccia Unlocking Aeneid 6.460Document72 pagesPelliccia Unlocking Aeneid 6.460gfvilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notices: Reality. (Papersfrom The Norwegian Institute at Athens3.) Pp. 178Document110 pagesNotices: Reality. (Papersfrom The Norwegian Institute at Athens3.) Pp. 178yasminePas encore d'évaluation

- Iliad and Alexiad PDFDocument8 pagesIliad and Alexiad PDFValee Gonzalez MoyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual - Walter BurkertDocument39 pagesGreek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual - Walter BurkertAlejandra Figueroa100% (1)

- The Wisdom of Lucian's TiresiasDocument2 pagesThe Wisdom of Lucian's TiresiasoakyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFDocument14 pagesThe Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFAlvah GoldbookPas encore d'évaluation

- Apuleius and AeneidDocument22 pagesApuleius and AeneidEduardoHenrikAubertPas encore d'évaluation

- f-cairns-virgils-augustan-epic-cambridge-university-press-1989-pp-xi-280-isbn-0-521-35358-0Document2 pagesf-cairns-virgils-augustan-epic-cambridge-university-press-1989-pp-xi-280-isbn-0-521-35358-0papadopulosmarie4Pas encore d'évaluation

- Menander: Plays of Adventure and Satire.1Document44 pagesMenander: Plays of Adventure and Satire.1gwegheffwey22e3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nietzsche's IdiosyncrasyDocument15 pagesNietzsche's IdiosyncrasyLaura Rodríguez FríasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Death of Patroclus in the IliadDocument16 pagesThe Death of Patroclus in the IliadmoOnykPas encore d'évaluation

- Mitchell - 2006 - Greeks, Barbarians and Aeschylus' SuppliantsDocument19 pagesMitchell - 2006 - Greeks, Barbarians and Aeschylus' SuppliantsphilodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- Early Images of Achilles and MemnonDocument26 pagesEarly Images of Achilles and Memnonreham el kassasPas encore d'évaluation

- Dido from Virgil to PurcellDocument22 pagesDido from Virgil to PurcellSecretaria Francisco RicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Phoenix and The Achaean Embassy: Three Achaean Envoys To Achilles, Have, Since AnDocument13 pagesPhoenix and The Achaean Embassy: Three Achaean Envoys To Achilles, Have, Since AnAlvah GoldbookPas encore d'évaluation

- GUTZWILLER, Kathryn J. Anyte's Epigram Book. Syllecta Classica. 1993Document10 pagesGUTZWILLER, Kathryn J. Anyte's Epigram Book. Syllecta Classica. 1993Mateus DukeviczPas encore d'évaluation

- Euripides "Telephus" Fr. 149 (Austin) and The Folk-Tale Origins of The Teuthranian ExpeditionDocument5 pagesEuripides "Telephus" Fr. 149 (Austin) and The Folk-Tale Origins of The Teuthranian Expeditionaristarchos76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Liapis TereusDocument20 pagesLiapis TereusSebastiana EnnePas encore d'évaluation

- Oedipodea PDFDocument13 pagesOedipodea PDFljlPas encore d'évaluation

- The Myth of Ariadne From Homer To CatullusDocument14 pagesThe Myth of Ariadne From Homer To Catulluscatarina:maiaPas encore d'évaluation

- R. B. RUTHERFORD. Tragic Form and Feeling in The IliadDocument16 pagesR. B. RUTHERFORD. Tragic Form and Feeling in The IliadbrunoPas encore d'évaluation

- Magic From The Asian Capital. in Any Case The: 1stromDocument8 pagesMagic From The Asian Capital. in Any Case The: 1stromJu Angélica LuzPas encore d'évaluation

- Gazis, G. (2012) Odyssey 11: The Power of Sight in The Invisible Realm'Document12 pagesGazis, G. (2012) Odyssey 11: The Power of Sight in The Invisible Realm'Pam ElaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cook 1992Document28 pagesCook 1992Tomislav BilicPas encore d'évaluation

- Nikolaev Argos MurioposDocument20 pagesNikolaev Argos MurioposalexandersnikolaevPas encore d'évaluation

- Staging Ajaxs Suicide2015 PDFDocument52 pagesStaging Ajaxs Suicide2015 PDFCarolina MarescottiPas encore d'évaluation

- Euripides VII. FragmentsDocument8 pagesEuripides VII. FragmentsozgucoPas encore d'évaluation

- Wbegt3700Document3 pagesWbegt3700824 99Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aristophanes - FROGS (Arrowsmith 1962)Document147 pagesAristophanes - FROGS (Arrowsmith 1962)Giordano Bruno100% (1)

- Easterling P. E. - Tragedy and Ritual (Cry 'Woe, Woe' But May The Good Prevail !) Metis - 1105-2201 - 1988 - Num - 3!1!907Document24 pagesEasterling P. E. - Tragedy and Ritual (Cry 'Woe, Woe' But May The Good Prevail !) Metis - 1105-2201 - 1988 - Num - 3!1!907VangelisPas encore d'évaluation

- Achilles in HadesDocument4 pagesAchilles in HadesRenato FO RomanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Some Aspects of The Theban Myth in The Lille StesichorusDocument5 pagesSome Aspects of The Theban Myth in The Lille StesichorusStauros PapadakisPas encore d'évaluation

- Oedipus Rex, Role of ChorusDocument3 pagesOedipus Rex, Role of ChorusShahzaib Malik67% (3)

- Torrance 2018Document4 pagesTorrance 2018Theo NashPas encore d'évaluation

- KONSTANTAKOS Zeus On See-Saw Additional Notes LogeionDocument12 pagesKONSTANTAKOS Zeus On See-Saw Additional Notes LogeionStratis SfakianosPas encore d'évaluation

- Moero of ByzantiumDocument22 pagesMoero of Byzantiummasanta11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Why Was Greek Mythology Such An Important Theme On Roman SarcophagiDocument4 pagesWhy Was Greek Mythology Such An Important Theme On Roman SarcophagiHaRvArD AlExAnDrOs CrOsSaLoTPas encore d'évaluation

- BENARDETE - Achilles and Hector The Homeric HeroDocument149 pagesBENARDETE - Achilles and Hector The Homeric HeroEpimetheus in the CavePas encore d'évaluation

- The Prometheus Bound.: Terminus Post QuernDocument3 pagesThe Prometheus Bound.: Terminus Post Quernpwyll pennannwfnPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Tragedy Sacrificial RitualDocument39 pagesGreek Tragedy Sacrificial RitualJoel MatthPas encore d'évaluation

- Butcher and Lang The OdysseyDocument326 pagesButcher and Lang The Odysseyapi-16639574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Athens in TragedyDocument5 pagesAthens in TragedyBernardoyDiomiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter Two The Origins and The Development of TragedyDocument6 pagesChapter Two The Origins and The Development of TragedymeghPas encore d'évaluation

- No Room for Ares in Children's BreastsDocument6 pagesNo Room for Ares in Children's Breastsალექსანდრე იაშაღაშვილიPas encore d'évaluation

- AristophanesfrogsDocument11 pagesAristophanesfrogsahorrorizadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Braund 1992 Juvenal Misogynist or MisogamistDocument16 pagesBraund 1992 Juvenal Misogynist or MisogamistDanieli MennittiPas encore d'évaluation

- Aeschylus' AmymoneDocument10 pagesAeschylus' AmymoneDavo Lo SchiavoPas encore d'évaluation

- 1969 Riddle Oedipus Isenberg PDFDocument40 pages1969 Riddle Oedipus Isenberg PDFFrank ViteriPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcestis Resurrected?: A Contemporary Analysis and Summary of The Evidence From Ancient SourcesDocument19 pagesAlcestis Resurrected?: A Contemporary Analysis and Summary of The Evidence From Ancient SourcesJames ScottPas encore d'évaluation

- AnalystsDocument4 pagesAnalystsDerrick IngramPas encore d'évaluation

- Euripides Reconsiders ClytemnestraDocument31 pagesEuripides Reconsiders ClytemnestraPatricia RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Kouremenos Similes JasonDocument18 pagesKouremenos Similes JasonFernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Carey - 2002 - A Tradition of Adventures in The Imperial GrottoDocument18 pagesCarey - 2002 - A Tradition of Adventures in The Imperial GrottophilodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- Colectia de Sange SpotDocument2 pagesColectia de Sange Spotcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DostoevskyDocument116 pagesDostoevskycalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Maestru Si MargaretaDocument44 pagesMaestru Si Margaretacalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DocumentDocument4 pagesDocumentcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Maestru Si MargaretaDocument6 pagesMaestru Si Margaretacalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- 4Document42 pages4calu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DocumentDocument9 pagesDocumentcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- EneidaDocument34 pagesEneidacalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DocumentDocument9 pagesDocumentcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- 3Document140 pages3calu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Idiot UlDocument18 pagesIdiot Ulcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- 1Document27 pages1calu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Essay The Old Man and The Young Wife - NotepadDocument4 pagesCritical Essay The Old Man and The Young Wife - Notepadcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Essay The Sovereignty of Marriage Versus The Wife's Obedience - NotepadDocument2 pagesCritical Essay The Sovereignty of Marriage Versus The Wife's Obedience - Notepadcalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Drama, From Everyman To Dr. FaustusDocument3 pagesDrama, From Everyman To Dr. Faustuscalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Elizabethan SonnetsDocument2 pagesElizabethan Sonnetscalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DecameroDocument49 pagesDecamerocalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- DecameroDocument49 pagesDecamerocalu balanPas encore d'évaluation

- Arms and The ManDocument16 pagesArms and The ManHaneen Al IbrahimPas encore d'évaluation

- Audio Scripts - Practice Test 2 PDFDocument8 pagesAudio Scripts - Practice Test 2 PDFWilliam PasiniPas encore d'évaluation

- American Pop Culture as Cold War PropagandaDocument5 pagesAmerican Pop Culture as Cold War Propagandaandi adnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Affairs: To Cite This Article: John Mitchiner (2009) THE OUSELEYS - A FAMILY INVOLVEMENTDocument16 pagesAsian Affairs: To Cite This Article: John Mitchiner (2009) THE OUSELEYS - A FAMILY INVOLVEMENTpavangirjapure1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Saliha Belmessous - Empire by Treaty - Negotiating European Expansion, 1600-1900-Oxford University Press (2014)Document305 pagesSaliha Belmessous - Empire by Treaty - Negotiating European Expansion, 1600-1900-Oxford University Press (2014)Anonymous laHwKo73ZPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Election Ad AnalysisDocument5 pages2016 Election Ad AnalysisALEXANDRIA JEAN BURROUGHESPas encore d'évaluation

- CrownDocument31 pagesCrownDaniel Ortiz100% (1)

- Test Bank For Intermediate Financial Management 13th Edition Eugene F Brigham Phillip R DavesDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Intermediate Financial Management 13th Edition Eugene F Brigham Phillip R DavesMichaelPruitttxzr100% (42)

- THE GOLDEN CHAIN - by Vladimir MossDocument160 pagesTHE GOLDEN CHAIN - by Vladimir MossVäterchenPas encore d'évaluation

- Blended Learning Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesBlended Learning Lesson Planapi-458892729Pas encore d'évaluation

- DCC RPG Quick Start GuideDocument6 pagesDCC RPG Quick Start GuideAnthony N. EmmelPas encore d'évaluation

- IELTS Academic Reading Mock Test 1Document15 pagesIELTS Academic Reading Mock Test 1amal thomas0% (1)

- The Field of Honor: Major Ben C. TrumanDocument606 pagesThe Field of Honor: Major Ben C. TrumanaxissixaPas encore d'évaluation

- U.S Withdrawal From AfghanistanDocument4 pagesU.S Withdrawal From AfghanistanSadiq JalalhshsPas encore d'évaluation

- Membrete Del PpeezDocument15 pagesMembrete Del Ppeezanon_57522396Pas encore d'évaluation

- Imam HussainDocument10 pagesImam Hussainb_rahman2k39603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Border Reiver Feud War RulesDocument11 pagesBorder Reiver Feud War RulesAnthony RhodesPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminism and The Interpretation of The Criminal Justice SystemDocument7 pagesFeminism and The Interpretation of The Criminal Justice SystembhaskarbanerjiPas encore d'évaluation

- Visual TrainingDocument35 pagesVisual TrainingTyson Urie100% (1)

- Fidel Castro: Early YearsDocument5 pagesFidel Castro: Early Yearsalexcharles433Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nimrod ReportDocument1 064 pagesNimrod Reportnelsontoyota100% (1)

- Cruz 2003 Phil International Law Book PDFDocument131 pagesCruz 2003 Phil International Law Book PDFSweet Zel Grace PorrasPas encore d'évaluation

- The Boy in The Striped Pajamas Full Text Holocaust PDFDocument112 pagesThe Boy in The Striped Pajamas Full Text Holocaust PDFindapantsPas encore d'évaluation

- Ben Urwand. The Collaboration, Hollywoods Pact With Hitler (2013)Document336 pagesBen Urwand. The Collaboration, Hollywoods Pact With Hitler (2013)Ilham Ghanem100% (1)

- Bud DajoDocument8 pagesBud DajoJoseph Lester Nala100% (2)

- What Dreams Were Made of - Movie Stars of The 1940s (PDFDrive)Document270 pagesWhat Dreams Were Made of - Movie Stars of The 1940s (PDFDrive)Sir SunePas encore d'évaluation

- InstaPDF - in Kargil War Heroes Saheed List With Photo 744Document6 pagesInstaPDF - in Kargil War Heroes Saheed List With Photo 744Neha ThakurPas encore d'évaluation

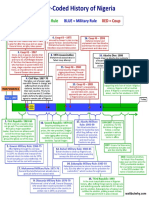

- Nigeria History3 PDFDocument1 pageNigeria History3 PDFViraj PanaraPas encore d'évaluation

- America's Sherlock Holmes - The Legacy of William Burns (PDFDrive)Document262 pagesAmerica's Sherlock Holmes - The Legacy of William Burns (PDFDrive)Wayne MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- TM9 710 1944Document360 pagesTM9 710 1944DarkLaborPas encore d'évaluation

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedD'Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (109)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondD'EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (3)

- The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the CovenantD'EverandThe Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the CovenantÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (177)

- The Disinformation Guide to Ancient Aliens, Lost Civilizations, Astonishing Archaeology & Hidden HistoryD'EverandThe Disinformation Guide to Ancient Aliens, Lost Civilizations, Astonishing Archaeology & Hidden HistoryPas encore d'évaluation

- Digging Up Armageddon: The Search for the Lost City of SolomonD'EverandDigging Up Armageddon: The Search for the Lost City of SolomonÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (12)

- The Anunnaki Chronicles: A Zecharia Sitchin ReaderD'EverandThe Anunnaki Chronicles: A Zecharia Sitchin ReaderÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (12)

- Holy Land: An Introduction to Biblical ArchaeologyD'EverandHoly Land: An Introduction to Biblical ArchaeologyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- Sex and Erotism in Ancient EgyptD'EverandSex and Erotism in Ancient EgyptÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (7)

- A Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became SapiensD'EverandA Pocket History of Human Evolution: How We Became SapiensÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (71)

- Rome Is Burning: Nero and the Fire That Ended a DynastyD'EverandRome Is Burning: Nero and the Fire That Ended a DynastyÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- There Were Giants Upon the Earth: Gods, Demigods, and Human Ancestry: The Evidence of Alien DNAD'EverandThere Were Giants Upon the Earth: Gods, Demigods, and Human Ancestry: The Evidence of Alien DNAPas encore d'évaluation

- The Anunnaki Chronicles: A Zecharia Sitchin ReaderD'EverandThe Anunnaki Chronicles: A Zecharia Sitchin ReaderÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (34)

- The Return of the Gods: Evidence of Extraterrestrial VisitationsD'EverandThe Return of the Gods: Evidence of Extraterrestrial VisitationsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (32)

- Fifty Things You Need to Know About World HistoryD'EverandFifty Things You Need to Know About World HistoryÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- A History of the World in Twelve ShipwrecksD'EverandA History of the World in Twelve ShipwrecksÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- The Lost World of the Old Ones: Discoveries in the Ancient SouthwestD'EverandThe Lost World of the Old Ones: Discoveries in the Ancient SouthwestÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- So Much Stuff: How Humans Discovered Tools, Invented Meaning, and Made More of EverythingD'EverandSo Much Stuff: How Humans Discovered Tools, Invented Meaning, and Made More of EverythingPas encore d'évaluation

- When Humans Nearly Vanished: The Catastrophic Explosion of the Toba VolcanoD'EverandWhen Humans Nearly Vanished: The Catastrophic Explosion of the Toba VolcanoÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (34)

- Dinosaurs: 101 Super Fun Facts And Amazing Pictures (Featuring The World's Top 16 Dinosaurs)D'EverandDinosaurs: 101 Super Fun Facts And Amazing Pictures (Featuring The World's Top 16 Dinosaurs)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- The Mystery of Doggerland: Atlantis in the North SeaD'EverandThe Mystery of Doggerland: Atlantis in the North SeaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- The Long Hangover: Putin's New Russia and the Ghosts of the PastD'EverandThe Long Hangover: Putin's New Russia and the Ghosts of the PastÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (76)

- Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient EgyptD'EverandRed Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient EgyptÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (65)

- The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern WorldD'EverandThe Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern WorldÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (187)

- Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient MysteriesD'EverandHidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient MysteriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- America Before: The Key to Earth's Lost CivilizationD'EverandAmerica Before: The Key to Earth's Lost CivilizationÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (29)

- Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban AgeD'EverandFour Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban AgeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)