Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Comparative Study of The Classroom Treatment of Male and Female Students of The Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro.

Transféré par

Alexander DeckerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Comparative Study of The Classroom Treatment of Male and Female Students of The Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro.

Transféré par

Alexander DeckerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Education and Practice ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.

9, 2013

www.iiste.org

A comparative study of the classroom treatment of male and female students of the Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro.

Olaitan W. Akinleke* Olusegun J. Omowunmi School of Management Studies, Federal Polytechnic, P.M.B. 50, Ilaro, Ogun State, Nigeria *E-mail of the corresponding author: akinleke4u@yahoo.com Abstract Following the increasing evidence of differentials in the educational opportunities and attainments of male and female students, especially in the underdeveloped countries, this study sets out to uncover the extent of such gender differences in Nigeria. Purposely, the study aims to discover whether male and female students perceive their classroom treatment (by faculty) and experiences differently; and whether there is any correlation between such perception and their academic performance. Using the College Student Experience Questionnaire (CSEQ), Third Edition (Pace, 1990), it was found that male and female students do not have any significant difference in their perception about classroom treatment and that there was a negative relationship between males and females attitude toward education. However, it was recommended that faculty should employ gender-neutral practices that promote equal opportunities for both male and female students. Keywords: classroom treatment, gender opportunities and academic achievement 1. Introduction Researchers have noted the evidence of a growing gender gap in educational achievement, both in the developed and underdeveloped countries (Fergusson & Horwood, 1997; Praat, 1999; Thiessen & Nickerson, 1999; Hillman & Rothman, 2003; and Weaver-Hightower, 2003). In the opinion of some researchers, (for example, Alton-Lee & Praat, 2001; Spelke, 2005; and Hyde & Linn, 2006), statics have revealed that females are outperforming males at all levels of the school system, attaining more school and post-school qualifications, and gaining admission into colleges in higher numbers. According to these researchers, these findings have caused extensive apprehension about male educational achievement and have led to huge assumption and discussion about the origin of gender differences in education. Konstantopoulos (2004) notes that research about the impact of school characteristics on students academic performance is of great interest as a stimulating school environment arouses the student to learn. According to him, it is very important to identify school factors that make schools more effective since schools differ substantially in impacting students academic achievement. Win and Miller (2004) noted that academic achievement at university can be viewed as a product of two sets of factors. The first set is each students unique combination of socioeconomic elements and ability while the second is the systems of education and patterns of imparting knowledge that are organised within schools. The interest of this paper lies in the influences of the second set. Marks, McMillan and Hillman (2001) argue that a higher level of confidence among students in their own ability, a school environment more conducive to learning, and a higher parental aspirations for the students education contribute to lifting student achievement. Danesty (2004) maintains that a combination of a healthy family background and the child learning in a helpful environment with a stimulated learning or instructional aids or motivational incentives will enhance academic performance. According to him, good teaching, counselling, good administration, good seating arrangement and good building produce high academic achievements and performance. Feingold (1988) notes that academic performance is affected by a host of factors, which include individual and household characteristics such as student ability, motivation, biological differences, parental and teacher expectations and behaviours, differential course taking and gender differences. Males are claimed to have larger average brain sizes than females and therefore, would be expected to have higher average IQs (Lynn, 1999; Allik, Must & Lynn, 1999; Colom & Lynn, 2004). Within the gender theory, there are series of complex and competing discourses regarding the line between gender and education. For instance, while some researchers have concluded that there was a significant difference in academic performance in a way that boys performed better than the girls, especially, in science subjects (Momanyi, Shadrack & Bernard, 2010; Mkpughe, 1998). According to this school of thought, men are 96

Journal of Education and Practice ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.9, 2013

www.iiste.org

regarded as having superior sex and as dominant as they intrinsically have better brains and learn much better than women. Other researchers have noted that although males have usually outperformed females in mathematics and science, this advantage seems to be vanishing as educational statistics are now indicating that females are outperforming males at all levels of the school system, obtaining more school and post-school qualifications, and attending university in higher numbers (Alton-Lee & Praat, 2001; Hillman & Rothman, 2003; Spelke, 2005; and Hyde & Lynn, 2006). These researchers explained that females tend to have better language abilities including essay writing skills, vocabulary and word fluency which promote better course work. Still, some other researchers have explained the achievement gap by examining factors such as differences in course taking behaviour, classroom experiences, cognitive processing and school factors (Fergusson & Horwood, 1997; Byrnes, Hong & Xing, 1997; and Young & Fisler, 2000). This group of researchers maintain that boys and girls are treated differently in coeducational classrooms and that they are encouraged to pursue interests and behave in ways that are thought to be typically male or typically female. For instance, Glasser (2004) finds that boys are often encouraged to answer more questions than girls and are expected to excel in mathematics and science classes while girls are expected to be better behaved and pursue more artistic and verbal interests such as literature and music. In a related research, The U.S. General Accounting Office (1996) reported that girls defer to boys in coeducational classrooms, are called on less than boys to participate in class activities, and are less likely than boys to study advanced mathematics and science. The growing debate that boys and girls learn differently has increased the interest in educational research since academic performance affects enrolment for college courses, career choices, and application of the acquired skills and vocations in future work settings. The intent of this study is to examine whether there are any gender differences in the perceived classroom treatment of the students of the Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro. 2. Participants Participants of this study were 204 (102 males and 102 females) students of the School of Management Studies in the Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro. They are all in their final year of the National Diploma program (NDII). Based on the stratified random sampling, the sample was representative of the entire departments of the Management School. Out of the two hundred and four students, two hundred and two students completed the questionnaire, which makes a response rate of 99%. 2.1 Instrument Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected for this study. To collect the qualitative facts, in-depth interviews were conducted with the eight lecturers that were in classrooms at the time that the study was being conducted. This is required for comparative assessment of students compliant behaviour while in classroom. To collect the quantitative data, the College Student Experience Questionnaire (CSEQ), Third Edition (Pace, 1990) was used. It is an 8-page questionnaire that on the average, any student can complete in less than 45 minutes (Pace, 1994). The questionnaire contains an array of demographic items, 8 College Environment scales that are designed to measure various aspects of the college environment, 14 College Activity scales that are designed to measure students effort in the learning process, and 23 Estimate of Gains scales designed to assess students evaluation of the outcomes of their college experience. Drew and Work (1998) had earlier used the scale in a study titled gender based differences in perception of experiences in higher education: gaining a broader perspective. According to them, the instrument has high reliability, relevant items, and has been used to collect a large amount of data from a wide variety of institutions. 3. Result and analysis The qualitative data that were gathered from the in-depth interview were reviewed while the quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS). Accordingly, the hypotheses in this study were tested using the t-test for independent samples and Pearson correlation coefficient.

97

Journal of Education and Practice ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.9, 2013

www.iiste.org

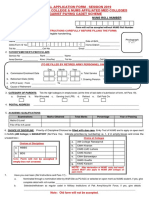

Independent sample test Table 1: Levenes test for equality of variances F Sig. T Df

Sig.(2tailed)

Mean differences

Std. Error difference

Equal variances assumed Perception of students Equal variances not assumed

.024

878

1.532

198

.127

-1.92

1.25

95% confidence interval of the difference Lower Upper -4.39 .55

1.532

197.995

.127

-1.92

1.25

-4.39

.55

The result in the table above indicates that female students perception about classroom treatment is not significantly different from that of the males (p>0.05). In other words, male and female students have similar views about educational experiences and attainments. Table 2: correlation of male and female attitudes to classroom treatment Male attitude to Female attitude education to education Male attitude to education Pearson correlation 1.000 -.104 Sig. (2-tailed) . .304 N 100 61 Female attitude to education Pearson correlation -.104 1.00 Sig. (2-tailed) .304 . N 102 61 Result in the table above indicates that there is a negative relationship between the males and females attitude toward education (since the correlation value is negative) although, the relationship is weak and is not significant (p>0.1). 4. Discussion The intention of this study was to examine the conditions under which Polytechnic students (both male and female) learn in Nigeria and to find out if their sex differences affect the way they are treated. Consequently, this researcher employed qualitative and quantitative research instruments that were administered on the students of the Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro, Ogun State, Nigeria. Both male and female students were studied. The study shows that there is no significant difference in the way that male and female students are treated in classrooms by their faculty. This result supports previous studies that have uncovered no evidence that male and female students are treated differently in college classrooms (Rienzi, Allen, Sarmiento & McMillan, 1993; Todd & Gerald, 1998; Polly, 2012). This result may be an indication that female students are now creating their own subculture that probably provides them social support and sense of security centred on the fact that worldwide, governments and societies are now generally more responsive to the girl-child education. The study also discovers a negative relationship between the attitudes of males and females toward education. Although, the relationship was weak and insignificant, which is an indication that gender is not the singular important factor in determining whether a student will effectually or ineffectually participate in class activities. This means that some other factors such as individual students cognitive abilities, school factors, socioeconomic status of the students, teachers own competence and so on may be importantly taking into consideration by faculty and school authorities when formulating their instructional guides and policies. 5. Conclusion and recommendation This study concludes that gender does not play any significant role on how students perceive their class experiences and interactions. Based on this conclusion, it could be recommended that teachers should engage in

98

Journal of Education and Practice ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.9, 2013

www.iiste.org

gender-neutral practices that promote equal opportunities for both males and females. Also, faculty need to identify the gender biases embedded in various educational materials and texts and take necessary educational materials and texts and take necessary steps to prevent such biases. Bailey (1992) argues that we need to look at the stories we are telling our students and children as far too many of our classroom examples, storybooks, and texts describe a world in which boys and men are bright, curious, brave, inventive, and powerful but girls and women are silent, passive and invisible. As a result, teachers need to create a learning environment that would be free of sex stereotyping in instructional organization, interactions, materials, and activities (Sanders, 2000). References Allik, J., Must, O., & Lynn, R. (1999). Sex differences on general intelligence among high school graduates: Some results from Estonia. Personality and Individual Differences, 26, 1137-1147. Alton-Lee, A., & Praat, A. (2001). Explaining and addressing gender differences in the New Zealand compulsory school sector. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Bailey, S. (1992) How Schools Short-change Girls: The AAUW Report. New York, NY: Marlowe & Company. Byrnes, J.P., Hong, L. & Xing, S. (1997). Gender differences on the math subject of the scholastic aptitude test may be culture-specific. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 34, 49-66. Colom, R. & Lynn, R. (2004). Testing the developmental theory of sex differences in intelligence on 12-18 year olds. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 75-82. Danesty, A.H. (2004). Psychosocial determinants of academic performance and vocational learning of students with disabilities in Oyo State. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ibadan. Dayioglu, M., & Turut-Asik, S. (2004). Gender differences in academic performance in a large public university in Turkey. Economic Research Centre. Retrieved from www.erc.metu.edu.tr Drew, T.L. & Work, G.G. (1998). Gender-based differences in perception of experiences in higher education: gaining a broader perspective. Journal of Higher education, 69(5), 542- 550. Fergusson, D.M. & Horwood, L.J. (1997). Gender differences in educational achievement in a New Zealand birth cohort .New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 32(1), 83-96. Glasser, D. (2004). Same-gender educator: Does Johnny learn better with Johnny? News for parents.org. Retrieved from http://www.newsforparents.org/nv_samegenderedu,htm. Hillman, K., & Rothman, S. (2003). Gender differences in educational and labour market outcomes. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. Hyde, J.S., & Linn, M.C. (2006). Gender similarities in mathematics performance. Science, 314(5799), 599-600. Kostantopoulos, S. (2006). Trends of School Effects on Student Achievement: Evidence from NLS:72, HSB:82, and NELS:92. Teachers College Record, 108(12), 2550-2581. Lynn, R. (1999). Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: A developmental theory. Intelligence, 27, 1-12. Marks, G., McMillan, J., & Hillman, K. (2001). Tertiary entrance performance; The role of student background and school factors. Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth, 22, Victoria: Australian Council for Educational Research, November. Mkpughe, M.L. (1998). The interaction of gender, location, and socio-economic status on students academic performance in home economics at the junior secondary school level. M.Ed. dissertation, DELSU, Abraka, Nigeria. Momanyi, J.M. Shadrack, O. & Misigo, B.L. (2010). Gender differences in self efficacy and academic performance in science subjects among secondary school students in Lugari district, Kenya. Educational Journal of Behavioural Science, 1(1), 62-77. Pace, C.R. (1990). College student experiences questionnaire (3rd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Centre for Postsecondary Research and Planning, Indiana University. Pace. C,R. (1994). College student experiences questionnaire: Information for prospective users. Bloomington, IN: Centre for Postsecondary Research and Planning, Indiana University. Polly, A.F. (2012). Understanding classroom interaction: students and professors contributions to students silence. Journal of Higher Education. Retrieved from www.findarticles.com Praat, A. (1999). Gender differences in student achievement and rates of participation in the school sector, 1986-1997: a summary report. The Research Bulletin, 10, 1-11. Rienzi, B.M., Allen, M.J., Sarmiento, Y.Q. & McMillin, J.D. (1993). Alumni perception of the impact of gender on their university experience. Journal of College Student Development, 34,154-157. Sanders, R. (2000). Gender equity in the classroom: An area for correspondence. Women's Research Quarterly, 28(3/4), 183-193. Spelke, E.S. (2005). Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science? A critical review. 99

Journal of Education and Practice ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.9, 2013

www.iiste.org

American Psychologist, 60(9), 950-958. Thiessen, V., & Nickerson, C. (1999). Canadian gender trends in education and work. Ottawa: Human Resources Development Canada Applied Research Branch. U.S. General Accounting Office (1996). Public Education: issues involving single-gender schools and programs. Washington D.C. Weaver-Hightower, M. (2003). The boy turn in research on gender and education. Review of Educational Research, 73(4), 471-498. Win, R. & Miller, P.W. (2004). The effects of individual and school factors on university students academic performance. The Centre for Labour Market Research. Young, J.W. & Fisler, J.L. (2000). Sex differences on the SAT: An analysis of demographic and educational variables. Research in Higher Education. 41, 401-416.

100

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- TOEFL Quide For Preparing For The TOEFL ExamDocument4 pagesTOEFL Quide For Preparing For The TOEFL ExammastertoeflPas encore d'évaluation

- DyscalculiaDocument212 pagesDyscalculiaCasé Castro100% (9)

- Nick Hoss Reading ListDocument19 pagesNick Hoss Reading ListKaps RamburnPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- TICO Manual 2012 eDocument142 pagesTICO Manual 2012 eVictoria Besleaga - CovalPas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiry (5E) Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesInquiry (5E) Lesson Plan Templateapi-487904244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesLesson Planzanderhero30100% (1)

- CCPS - Process Safety in Action Annual Report and ChartDocument25 pagesCCPS - Process Safety in Action Annual Report and Chartkanakarao1100% (1)

- Simple Research in ReadingDocument25 pagesSimple Research in ReadingJosenia Constantino100% (5)

- Sequencing Lesson Plan#1Document7 pagesSequencing Lesson Plan#1natalies15Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Styles: Higher Education ServicesDocument8 pagesLearning Styles: Higher Education Servicesandi sri mutmainnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Availability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateDocument13 pagesAvailability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesDocument9 pagesAssessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Availability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesDocument8 pagesAvailability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaDocument7 pagesAssessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsDocument17 pagesAssessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Asymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelDocument17 pagesAsymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisDocument17 pagesAssessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Barriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsDocument8 pagesBarriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateAlexander Decker100% (1)

- Assessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowDocument15 pagesAssessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorDocument12 pagesAssessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Attitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshDocument12 pagesAttitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossDocument5 pagesAssessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsDocument7 pagesAssessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Are Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsDocument10 pagesAre Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryDocument14 pagesApplication of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationDocument12 pagesAntibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesDocument8 pagesAntioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaDocument10 pagesAssessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Applying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaDocument13 pagesApplying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaDocument8 pagesAssessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaDocument11 pagesAssessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaDocument9 pagesAnalyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- An Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanDocument10 pagesAn Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceDocument10 pagesAnalysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Application of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Document10 pagesApplication of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Alexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceAlexander DeckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus AssignmentDocument4 pagesSyllabus Assignmentapi-269308807Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bonnie Hagemann Full Bio 2013Document3 pagesBonnie Hagemann Full Bio 2013Bonnie HagemannPas encore d'évaluation

- Column JoyceDocument55 pagesColumn JoyceKlarissa JsaninPas encore d'évaluation

- Mae EDUC 6Document2 pagesMae EDUC 6Mary Jean OlivoPas encore d'évaluation

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Huma7323.001.07s Taught by Elke Matijevich (Exm017100)Document4 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Huma7323.001.07s Taught by Elke Matijevich (Exm017100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupPas encore d'évaluation

- Writing - Free Writing Short NarrativeDocument11 pagesWriting - Free Writing Short NarrativeSaravana SelvakumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Platt CV March13Document6 pagesPlatt CV March13Julie AlexanderPas encore d'évaluation

- T Taallkkiin NGG Ssttiicckk: Looking Back On 2003Document8 pagesT Taallkkiin NGG Ssttiicckk: Looking Back On 2003RouboutsouAthinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dances Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDances Lesson Planapi-269567696Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fiche 4 TaxiDocument2 pagesFiche 4 TaximetalmightPas encore d'évaluation

- RPH MT 3Document1 pageRPH MT 3Linford Christie YosuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Conceptions of Algebraic Reasoning in The Primary GradesDocument22 pagesDeveloping Conceptions of Algebraic Reasoning in The Primary GradesGreySiPas encore d'évaluation

- QuotesDocument31 pagesQuotespooja_08Pas encore d'évaluation

- T3904-390-02 SG-Ins Exc EN PDFDocument89 pagesT3904-390-02 SG-Ins Exc EN PDFBrunoPanutoPas encore d'évaluation

- Julie FranksresumeDocument4 pagesJulie Franksresumeapi-120551040Pas encore d'évaluation

- University of Sheffield - PHI103 - Self and Society - 2013 - SyllabusDocument6 pagesUniversity of Sheffield - PHI103 - Self and Society - 2013 - Syllabusna900Pas encore d'évaluation

- Semi Final AnswerDocument15 pagesSemi Final AnswerHiezel G LandichoPas encore d'évaluation

- Team Dynamics: Mcshane/Von Glinow M:Ob 3EDocument26 pagesTeam Dynamics: Mcshane/Von Glinow M:Ob 3EMuraliPas encore d'évaluation

- Techniques For Testing ReadingDocument26 pagesTechniques For Testing ReadingIrene WongPas encore d'évaluation

- Med 2019 NumsDocument6 pagesMed 2019 NumsTalha GulPas encore d'évaluation