Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Crisis Literature Review

Transféré par

letter2lalDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Crisis Literature Review

Transféré par

letter2lalDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

General deregulations of financial markets and improper risk management have seriously shaken banking systems worldwide during

the global financial crisis. The key challenge in the upcoming period is to find an optimum balance between necessary regulation and avoiding overregulation that could jeopardize competitiveness of the banking system. The emphasis should not confine to the capital adequacy ratio but it should also cover liquidity because problems with insufficient liquidity could bring a crisis even to a bank that otherwise meets the statutory solvency criteria. The Montenegrin banking sector was no exception and it was severely hit by the crisis. This paper shows the movement of the banking system indicators through the following stages: preventive actions, strengthening of resilience, and crisis management. In addition, the paper shows the process of the banking system restructuring, followed by the conclusion that there can be no banking system restructuring without the restructuring of the real economy.

Introductory remarks

Crises have emerged in the past and they will reappear in the future. They were results of various factors but generally, as L. Santa (2007) notes, the basic underlying reasons for the crises appearance are the inefficient and imperfect functioning of financial markets and the asymmetrical information emerging in markets. Central banks cannot prevent all crises, but what they can and must do is mini6 Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice mize their costs and act preventively. In the past, central banks mainly focused on price stability and, as indicated in the IMF (2004) policy paper Central Banking Lessons from the Crisis, they tended to focus less on financial system developments and built-up vulnerabilities. That is why one of the underlying culprits

of the current crisis is improper risk management. Even in normal times banks face numerous risks that only multiply in a crisis. As D. Ware (1996) indicates, the risks to which banks are exposed can be categorized as: 1. Credit risk the risk that the banks counterparty might not pay on the

due date; 2. Liquidity risk the risk that the bank might itself fail to meet its obligations when they fall due; 3. Yield risk the risk that the banks assets may generate less income than

the expense generated by its liabilities; 4. Market risk the risk of loss arising from assets (primarily bonds, foreign

exchange, and the like) in which the bank has a position; 5. 6. Operational risk the risk of a failure in the banks procedures or controls; Ownership/management risk the risk that the owners/management

might have goals that are contrary to sound banking operations.1 All bank activities undeniably involve consideration of operational risk since profit, as the ultimate objective, can be generated only if certain risks are taken. However, risk taking requires proper risk treatment to prevent jeopardizing banking operations. That is why the general banking objectives should be risk taking as well as risk management, diminishing, and the finding of an optimum balance between risk and profit, that is, a proper rate of return on equity. However, being sometimes motivated by short-term objectives, banks engage in excessive risk-taking. Inadequate implementation of risk management standards, coupled with the lack of proper regulation, directly generate capital decrease and increase liquidity risk in banking operations, which are the problems that consequently increase the risk of a crisis emergence. Deregulation or insufficient regulation leads to growing risks which taking could

bring higher profit. Therefore, higher profit may be the result of excessive taking and accumulation of risks. Consequently, this contributes to growing competition, yet only in short term. In the long term, inadequate risk management and excessive risk taking may jeopardize not only competitiveness but operational stability of institutions as well. Regulation and efficiency (competitiveness) are often conflicting objectives. On one hand, a rigid and voluminous regulatory framework may seem reliable yet restrictive to, inter alia, bank lending activity, and thus to contraction in the real economy. Another negative impact is the risk that banks would attempt to avoid such requirements while adjusting to new regulations. There are examples of a more rigid banking regulation that has led to unfair competition among banks and nonbanking institutions. The example of Japanese banks` operations in international market has confirmed this impact on their competitiveness. Due to the fact that the Japanese regulatory framework allowed lower capital requirements for banks and more flexibility with regard to risk-weighted assets, the Japanese banks strengthened their competitiveness through their subsidiaries in other markets in relation to similar institutions in those markets, thus pointing to the manner how a weaker regulation affects competition increase, that is, to the inconsistency of regulation and competition. In such conditions, it is necessary for the regulator to take proper measures to prevent excessive risks. In this regard, the CBCG approach to maintaining financial stability can be described as a policy involving three lines of defence. The first line is prevention, the second one is increasing the systems resilience to shocks, and the third line is crisis management. All three dimensions are equally important though not having the same implications.

Review of literature

The field of crisis management currently faces two important limitations. First, this field has been distinguished by two major approaches to date, crisis management planning and analysis of organizational contingencies. However, despite what we have learned from these approaches, neither seems to lead to a crisis management learning model that fosters organizational resilience in coping with crises. Secondly, researchers have studied a number of events as case studies but have never synthesized these case studies. Consequently, each crisis seems idiosyncratic and administrators continue to repeat the same errors when a crisis occurs. The research proposal presented in this paper aims to remove these limitations by bringing together two apparently opposing fields of study, that of crisis management, characterized by what are perceived as specific events, and that of organizational development, characterized by the strengthening of organizations capacities to cope with lasting changes. This paper proposes to explore their potential to work together theoretically and empirically through a research design.

IMPORTANCE OF THE SUBJECT Contrary to a widely-held, persistent belief, crises in contemporary societies can no longer be considered improbable and rare events (Rosenthal & Kouzmin,1996). The occurrence and diversity of types of crisis in our societies have increased (Hart & al., 2001; Quarantelli, 2001; Robert & Lajtha, 2002). Moreover, the time frame of crises has tended to expand (Rosenthal & Kouzmin, 1996; Hart & Boin, 2001), along with their geographic spread (Hart et al., 2001; Michel-Kerjan, 2003). Crisis management is on the public administration agenda and decision-makers are increasingly put on the carpet and pressed

for answers on issues which they often find overwhelming (Drabek & Hoetmer, 1991; Pauchant & Mitroff, 1995; Boin & Lagadec, 2000). Despite accumulated experience in facing disasters, governmental responses are still inept (Piotrowski, 2006; Van Heerden, 2006).The extensive media coverage of events is too frequently oriented towards identifying the guilty rather than looking for solutions. Finally, the costs of catastrophes continue to grow (Nathan, 2000; Newkirk, 2001) and the insecurity is in all the spirits (Michel-Kerjan, 2003). These are the new realities organizations confront that require a fresh perspective on the issue of crisis management practice, as well as in the area of research. 2 CURRENT STATE OF THE CRISIS MANAGEMENT LITERATURE Since the start of the 1980s, the field of crisis management has been characterized by two main trends: planning in crisis management and the analysis of organizational contingencies during a crisis. The literature on crisis management planning consists of a number of normative pronouncements aimed at increasing the efficiency of crisis interventions. Their authors highlight the need for emergency planning (Lagadec, 1991, 1996; Counts & Prowant, 1994; Perry & Nigg, 1985; Denis, 1993, 2002; Bugge, 1993; Sylves & Pavalak; Quarantelli, 1996), defining actions in relation to the various phases of the evolution of a crisis starting with the detection of warning signs up to post-crisis activities (Drabek & Hoetmer, 1991), stressing the development of a culture of security, both within organizations and in the population at large (Lagadec, 1991; Tazieff, 1988; Denis, 1993, 2002; Toft & Reynolds, 1994; Pauchant, 1997), and the training and sensitization of leaders to their roles in times of crisis (Perry & Nigg, 1985; Lagadec, 1991, 1996, 1997; Kuban, 1995; Petak, 1985; Pauchant & Mitroff, 1995). Generalizing about crises has led several researchers including Reason (1997) to develop the high reliability organizations model. This model was largely inspired by experiences in security and risk

management in the area of airlines, aerospace and nuclear energy. This model scrutinizes the chain of production and identifies the critical processes and/or normal operations that constitute areas of weakness or risk (near miss). Attempts to export this model have been made, notably in the medical world and the health sector in general with a view to guaranteeing a more secure provision of care. Unfortunately, administrators are still unfamiliar with this model (Bourrier, 2002). Moreover, it is criticized by some authors (Sagan, 1993; Perrow, 1994) for its lack of realism. In addition, this model seems to apply more to large industry and to the redesigning of its technical operations and technologies, and little or not at all to small and medium-sized enterprises, or to organizations having a role as social interveners during crises.

3 CONTRIBUTION OF ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENT TO CRISIS MANAGEMENT PRACTICES The concept of learning is increasingly central to crisis management researchers concerns (Roux-Dufort, 2000; Simon & Pauchant, 2000; Stern, 1997). They are seeking models allowing for a lasting integration of organizational learning during crises. Therefore, such models remain largely to be created and invented (Roux-Dufort, 2000). The challenge is to transfer the accumulated knowledge flowing from concrete experiences, well-documented by crisis management researchers (in other words, reliable data), to a learning model in which organizational actors will be actively engaged. One of the avenues to better integrate this learning seems to us to be found in organizational development approaches. As Piotrowski (2006: 11) pointed out, undoubtedly, OD practitioners and researchers will be relied upon by private and public organizations, governmental administrations, small businesses and large corporations. Organizational development (OD) can be defined as a process calling upon social and behavioural sciences to strengthen abilities and capacities

of organizations over the long term to confront changes and to better attain their objectives (Cummings & Worley, 2005). OD is a field of practical application based on a process of accompaniment, initiated either internally or externally (Schein, 1999) and covering a vast panoply of activities (Church & al., 1994, Bazigos & Church, 1997; Worren & al., 1999; Carter & al., 2001, 2005; Rothwell & Sullivan, 2005; French & Bell, 1999): researchaction; organizational diagnosis at various levels (individualgrouporganization); feedback mechanisms for members of the organization (such as survey feedback, search conferencing, coaching, etc.); and the design of interventions at the level of human processes, technostructure, human resource management, global strategy, etc. These methods allow organizational actors to master new knowledge and ways of doing things. This idea of strengthening organizational abilities and capacities is also related to the notion of resilience put forward by Quarantelli (2001) and Rosenthal & Kouzmin (1996). Furthermore, OD may represent what Bourrier (2002) calls the missing link and thus address the concern about crisis management over a period of time through reconfiguring interventions and the support structures of these interventions. The field of OD seems to us particularly well-placed to effect this necessary transfer of theoretical knowledge into practice. The literature on organizational learning is vast but that which relates learning and crisis management is rather meagre. Indeed, we know a little more about the types and modes of learning but we do not know whether these apply to crisis management. Finally, the models described to date by researchers have remained rather theoretical and have seldom been applied.

Conclusion As Ugolini (2003) points out, it is clear that challenges to financial stability arise, and will continue to arise, whether central banks are ready for them or not. Central banks have to be ready and have to learn important lessons from previous lessons. As Paul Krugman pointed out, the lesson to be learned from the global financial crisis is that everything that needs to be saved in the period of crisis, because it is of crucial significance for financial mechanisms, should be regulated in the crisis free period for the purpose of prevention of excessive risk taking. It is obvious that excessive deregulation, in combination with inadequate risk management, was the seed for present problems. On the other hand, it would be dangerous to go to the other extreme, excessive regulation, because it aggravates competitiveness. The key challenge is to find a proper balance between regulation and preserving the banking sectors competitiveness. Bank capital is the buffer for bank loss to be used to prevent bank failures. Sometimes, a high amount of capital is insufficient for a banks stability if there is insufficient liquidity, which may become a direct trigger of problems and bank

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Current Trends and Issues in Nursing ManagementDocument8 pagesCurrent Trends and Issues in Nursing ManagementMadhu Bala81% (21)

- Backwards Design - Jessica W Maddison CDocument20 pagesBackwards Design - Jessica W Maddison Capi-451306299100% (1)

- SurveyingDocument26 pagesSurveyingDenise Ann Cuenca25% (4)

- Microfinance Ass 1Document15 pagesMicrofinance Ass 1Willard MusengeyiPas encore d'évaluation

- GST SuvidaDocument3 pagesGST Suvidaletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Airline QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesAirline Questionnaireletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- GST SuvidaDocument3 pagesGST Suvidaletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Retail Store ImageDocument19 pagesRetail Store Imagehmaryus0% (1)

- Heath LedgerDocument37 pagesHeath Ledgerletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- ABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing TraitsDocument1 pageABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing Traitsletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Wagon SoftwareandHardwareDescriptionDocument1 pageWagon SoftwareandHardwareDescriptionletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Master Report TASEVSKIv3Document94 pagesPost Master Report TASEVSKIv3moooPas encore d'évaluation

- ABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing TraitsDocument1 pageABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing Traitsletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

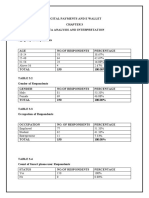

- Digital PaymentDocument8 pagesDigital Paymentletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Online Food Delivering CompaniesDocument62 pagesOnline Food Delivering Companiesletter2lal67% (3)

- HR PDFDocument13 pagesHR PDFletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Airline QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesAirline Questionnaireletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Secularism Project A Study of Compatibility of Anti Conversion Laws With Right To Freedom NewDocument43 pagesSecularism Project A Study of Compatibility of Anti Conversion Laws With Right To Freedom Newletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Black Book PDFDocument69 pagesBlack Book PDFManjodh Singh BassiPas encore d'évaluation

- WagonVendor SynopsisDocument2 pagesWagonVendor Synopsisletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Changes To Be DoneDocument2 pagesChanges To Be Doneletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- JAVA Syllabus PDFDocument2 pagesJAVA Syllabus PDFletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Vishnu New1Document7 pagesVishnu New1letter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Co PRIVACY PDFDocument7 pagesCo PRIVACY PDFletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi Banking Transaction SystemDocument4 pagesMulti Banking Transaction Systemletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Multi Banking Transaction SystemDocument4 pagesMulti Banking Transaction Systemletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Gokul........ A Study On Product Positioning at TVS MotorsDocument101 pagesGokul........ A Study On Product Positioning at TVS Motorsletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Wagon ExistingProposedDocument1 pageWagon ExistingProposedletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- 65 2 37 395 PDFDocument6 pages65 2 37 395 PDFletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Joomla Training SyllabusDocument2 pagesJoomla Training Syllabusletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation JyothiDocument27 pagesPresentation Jyothiletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Spiritual QuestionaireDocument4 pagesSpiritual Questionaireletter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Adolescents in IndiaDocument250 pagesAdolescents in Indialetter2lalPas encore d'évaluation

- Financeprojectstopics 120612234846 Phpapp02Document64 pagesFinanceprojectstopics 120612234846 Phpapp02Garima SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Stucor Qp-Ec8095Document16 pagesStucor Qp-Ec8095JohnsondassPas encore d'évaluation

- The Reason: B. FlowsDocument4 pagesThe Reason: B. FlowsAryanti UrsullahPas encore d'évaluation

- MolnarDocument8 pagesMolnarMaDzik MaDzikowskaPas encore d'évaluation

- LPS 1131-Issue 1.2-Requirements and Testing Methods For Pumps For Automatic Sprinkler Installation Pump Sets PDFDocument19 pagesLPS 1131-Issue 1.2-Requirements and Testing Methods For Pumps For Automatic Sprinkler Installation Pump Sets PDFHazem HabibPas encore d'évaluation

- Week - 2 Lab - 1 - Part I Lab Aim: Basic Programming Concepts, Python InstallationDocument13 pagesWeek - 2 Lab - 1 - Part I Lab Aim: Basic Programming Concepts, Python InstallationSahil Shah100% (1)

- Priest, Graham - The Logic of The Catuskoti (2010)Document31 pagesPriest, Graham - The Logic of The Catuskoti (2010)Alan Ruiz100% (1)

- Cambridge IGCSE: CHEMISTRY 0620/42Document12 pagesCambridge IGCSE: CHEMISTRY 0620/42Khairun nissaPas encore d'évaluation

- Marine Cargo InsuranceDocument72 pagesMarine Cargo InsuranceKhanh Duyen Nguyen HuynhPas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Electronics Chapter 5Document30 pagesDigital Electronics Chapter 5Pious TraderPas encore d'évaluation

- CTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Document45 pagesCTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Resort1.7 Mri100% (1)

- Beyond Models and Metaphors Complexity Theory, Systems Thinking and - Bousquet & CurtisDocument21 pagesBeyond Models and Metaphors Complexity Theory, Systems Thinking and - Bousquet & CurtisEra B. LargisPas encore d'évaluation

- Module-29A: Energy MethodsDocument2 pagesModule-29A: Energy MethodsjhacademyhydPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 Q3 Figure Life DrawingDocument10 pagesLesson 1 Q3 Figure Life DrawingCAHAPPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioinformatics Computing II: MotivationDocument7 pagesBioinformatics Computing II: MotivationTasmia SaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Project ProposalDocument4 pagesProject Proposaljiaclaire2998100% (1)

- Dessler HRM12e PPT 01Document30 pagesDessler HRM12e PPT 01harryjohnlyallPas encore d'évaluation

- Liquitex Soft Body BookletDocument12 pagesLiquitex Soft Body Booklethello belloPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Mobility and SafetyDocument77 pagesE-Mobility and SafetySantosh KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Maha Vedha DikshaDocument1 pageMaha Vedha DikshaBallakrishnen SubramaniamPas encore d'évaluation

- ইসলাম ও আধুনিকতা – মুফতি মুহম্মদ তকী উসমানীDocument118 pagesইসলাম ও আধুনিকতা – মুফতি মুহম্মদ তকী উসমানীMd SallauddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Internship Format HRMI620Document4 pagesInternship Format HRMI620nimra tariqPas encore d'évaluation

- KCG-2001I Service ManualDocument5 pagesKCG-2001I Service ManualPatrick BouffardPas encore d'évaluation

- ACCA F2 2012 NotesDocument18 pagesACCA F2 2012 NotesThe ExP GroupPas encore d'évaluation

- 1500 Series: Pull Force Range: 10-12 Lbs (44-53 N) Hold Force Range: 19-28 Lbs (85-125 N)Document2 pages1500 Series: Pull Force Range: 10-12 Lbs (44-53 N) Hold Force Range: 19-28 Lbs (85-125 N)Mario FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- RECYFIX STANDARD 100 Tipe 010 MW - C250Document2 pagesRECYFIX STANDARD 100 Tipe 010 MW - C250Dadang KurniaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lightning Protection Measures NewDocument9 pagesLightning Protection Measures NewjithishPas encore d'évaluation