Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Ayya Khema

Transféré par

Calvin Sweatsa LotDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Ayya Khema

Transféré par

Calvin Sweatsa LotDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

http://www.dhammatalks.net/Books8/Ayya_Khema_The_Meditative_Mind.

pdf Without the meditative mind and experience, the dharma cannot arise in the heart, because the dharma is not in words.

Clear comprehension has four aspects to it. First: What is my purpose in thinking, talking or doing? Thought, speech and action are our three doors. Second: Am I using the mostskillful means for my purpose? That needs wisdom and discrimination. Third: Are these means within the dharma? This means knowing the distinction between wholesome and unwholesome. The thought process needs our primary attention, because speech and action will follow from it. Sometimes people think that the end justifies the means. It doesnt. Both means and end have to be within the dharma. And fourth: "Has my purpose been accomplished, and if not, why not?"

A meditative mind is achieved through mindfulness, clear comprehension and calming the senses. These three aspects of practice need to be done in everyday life. Peace and harmony will result, and our meditation will flourish.

If we watch our senses again and again, this becomes a habit, and is no longer difficult. Life will be much more peaceful. The world as we know it consists of so much proliferation. Everywhere are different colors, shapes,

beings and natures growth. Each species of tree has hundreds of subspecies. Nature proliferates. All of us look different. If we dont guard our senses, this proliferation in the world will keep us attracted life after life. Theres too much to see, do, know and react to. Since there is no end to all of that we might as well stop and delve inside of ourselves.

We should neither believe nor disbelieve what we hear or read, but try it out ourselves.

To use other people as our mirror is very helpful because they reflect our own being. We can only see in others what we already know about ourselves. The rest is lost to us.

If we add clear comprehension to our mindfulness and check our purpose and skillful means we will eliminate much grief and worry. We will develop an awareness which will make every day, every moment an adventure. Most people feel bogged

down and burdened. Either they have too much or too little to do; not enough money to do what they like or they frantically move about trying to occupy themselves. Everybody wants to escape from unsatisfactory conditions, but the escape mechanism that each one chooses does not provide real inner joy. However with mindfulness and clear comprehension, just watching a tree is fascinating.

External mindfulness also means to see a tree, for instance, in a completely new way. Not with the usual thoughts of thats pretty, or I like this one in my garden, but rather noticing that there are live and dead leaves, that there are growing plants, mature ones and dying ones. We can witness the growth, birth and decay all around us. We can understand craving very clearly by watching ants, mosquitoes, dogs. We need not look at them as a nuisance, but as teachers. Ants, mosquitoes and barking dogs are the kind of teachers who dont leave us alone until the lessons are fully learned. When we see all in the light of birth, decay, death, greed, hate and delusion, we are looking in a mirror of all life around us, then we have dharma on show. All of us are proclaiming the truth of dharma constantly, only we dont pay enough attention.

Peoples hearts and minds usually contain equal amounts of flowers and weeds. Were born with the three roots of evil: greed, hate and delusion, and the three roots of good: generosity, lovingkindness and wisdom. Doesnt it make sense to try and get rid of those three roots which are the generators of all problems, all our unpleasant

experiences and reactions?

Two aspects of importance are mindfulness and the calming of the senses. Internal mindfulness may sometimes be exchanged for external mindfulness because under some circumstances that is an esThe Meditative Mind There is this difference between one who knows and one who practices.30 sential part of practice. The world impinges upon us, which we cannot deny

Caused by delusion, we manifest greed and hate. There are different facets of greed and hate, and the simplest and most common one is I like, I want, I dont like, and I dont want. Most people think such reactions are perfectly justified, and yet that is greed and hate.

. Our roots have sprouted in so many different ways that we have all sorts of weeds growing. If we look at a garden we will find possibly thirty or forty different types of weeds. We might have that many or more unwholesome thoughts and emotions. They have different appearances and power but theyre all coming from the same roots.

. As we cant get at the roots yet, we have to deal with what is above the surface. When we cultivate the good roots, they become so mighty and strong that the weeds do not find enough nourishment any more. As long as we allow room for the weeds in our garden, we take the nutriment away from the beautiful plants, instead of cultivating those more and more. This takes place as a development in daily living, which then makes it possible to meditate as a natural outcome of our state of mind.

There is this difference between one who knows and one who practices.

On the spiritual path, there's nothing to get, and everything to get rid of. Obviously, the first thing to let go of is trying to "get" love, and instead to give it. That's the secret of the spiritual path. One has to give oneself wholeheartedly. Whatever we do half heartedly, brings halfhearted results. How can we give ourselves? By not holding back.By not wanting for ourselves. If we want to be loved, we are looking for a support system. If we want to love, we are looking for spiritual growth. Disliking others is far too easy. Anybody can do it and justify it because, of course, people are often not very bright and don't act the way we'd like them to act. Disliking makes grooves in the heart, and it becomes easier and easier to fall into these grooves. We not only dislike others, but also ourselves.

http://www.cebtm.net/CEBtM%20Sources/WHAT%20LOVE%20IS.pdf s. If one likes or loves oneself, it's easier to love others, which is why we always start loving-kindness meditations with the focus on ourselves. That's not egocentricity. If we don't like ourselves because we have faults, or have made mistakes, we will transfer that dislike to others and judge them accordingly. We are not here to be judge and jury. First of all, we don't even have the qualifications. It's also a very unsatisfactory job, doesn't pay, and just makes people unhappy.

People often feel that it's necessary to be that way to protect themselves. But what do we need to protect ourselves from? We have to protect our bodies from injury. Do we have to protect ourselves from love? We are all in this together, living on this planet at the same time, breathing the same air. We all have the same limbs, thoughts, and emotions. The idea that we are separate beings is an illusion. If we practice meditation diligently with perseverance, then one day we'll get over this illusion of separation. Meditation makes it possible to see the totality of all manifestation. There is one creation and we are all part of it. What can we be afraid of?

We are afraid to love ourselves, afraid to love creation, afraid to love others because we know negative things about ourselves. Knowing that we do things wrong, that we have unhappy or unwholesome thoughts, is no reason not to love. A mother who loves her children doesn't stop loving them when they act silly or unpleasant. Small children have hundreds of unwholesome thoughts a day and give voice to them quite loudly. We have them too, but we do not express them all.

So, if a mother can love a child who is making difficulties for her, why can't we love ourselves? Loving oneself and knowing oneself are not the same thing. Love is the warmth of the heart, the connectedness, the protection, the caring, the concern, the embrace that comes from acceptance and understanding for oneself. Having practiced that, we are in a much better position to practice love toward others. They are just as unlovable as we are, and they have just as many unwholesome thoughts. But that doesn't matter. We are not judge and jury. When we realize that we can actually love ourselves, there is a feeling of being at ease. We don't constantly have to become or pretend, or strive to be somebody. We can just be. It's nice to just be, and not be "somebody." Love makes that possible. By the same token, when we relate to other people, we can let them just be and love them. We all have daily opportunities to practice this. It's a skill, like any other.

If we see quite clearly that love is a quality that we all have, then we can start developing that ability. Any skill that we have, we have developed through practice. If we've learned to type, we've had to practice. We can practice love and eventually we'll have that skill. Love has nothing to do with finding somebody who is worth loving, or checking out people to see whether they are

truly lovable. If we investigate ourselves honestly enough, we find that we're not all that lovable either, so why do we expect somebody else to be totally lovable? It has nothing to do with the qualities of the other person, or whether he or she wants to be loved, is going to love us back, or needs love. Everyone needs love. Because we know our own faults, when somebody loves us we think, Oh, that's great, this person loves me and doesn't even know I have all these problems. We're looking for somebody to love us to support a certain image of ourselves. If we can't find anybody, we feel bereft. People even get depressed or search for escape routes. These are wrong ways of going at it.

In all developed societies there are institutions to foster the expansion of the mind, from the age of three until death. But we don't have any institutions to develop the heart, so we have to do it ourselves.

Most people are either waiting for or relating to the one person who makes it possible for them to feel love at last. But that kind of love is beset with fear, and fear is part of hate. What we hate is the idea that this special person may die, walk away, have other feelings and thoughtsin other words, the fear that love may end, because we believe that love is situated strictly in that one person. . Since there are six billion people on this planet, this is rather absurd. Yet most people think that our love-ability is dependent upon one person and having that one person near us. That creates the fear of loss, and love beset by fear cannot be pure. We create a dependency upon that person, and on his or her ideas and emotions. There is no freedom in that, no freedom to love.

I think everybody knows that above us is the sky and not heaven. We have heaven and hell within us and can experience this quite easily. So even without having complete concentration in meditation and profound insights, the Four Divine Abidings, or Supreme Emotions, enable us to

live on a level of truth and lovingness, security, and certainty, which gives life a totally different quality. When we are able to arouse love in our hearts without any cause, just because love is the heart's quality, we feel secure.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/khema/allofus.html

The arising and ceasing phenomena, which are our teachers, never take a rest. Dhamma is being taught to us constantly. All our waking moments are Dhamma teachers, if we make them so. The Dhamma is the truth expounded by the Enlightened One, which is the law of nature surrounding us and imbedded within us.

Everyone needs a good friend, who has enough selflessness, not only to be helpful, but also to point out when one is slipping. Treading the Dhamma path is like walking a tightrope. It leads along one straight line and every time one slips, one hurts. If we have a painful feeling inside, we're no longer on the tightrope of the Dhamma.

One can be fooled by a person's beautiful words or splendid appearance. The character of a person is shown not only in words, but in the small day-to-day activities. One of the very important guidelines to a person's character is how they react when things go wrong. It's easy to be loving, helpful and friendly when everything goes well, but when difficulties arise our endurance and patience are being tested as well as our equanimity and determination. The less egoconsciousness one has, the easier one can handle all situations.

The only thing that is real is that we have six roots within us. Three roots of good and three roots of evil. The latter are greed, hate and delusion, but we also have their opposites: generosity, loving-kindness and wisdom. Take an interest in this matter. If one investigates this and doesn't get anxious about it, then one can easily accept these six roots in everybody. No difficulty at all, when one has seen them in oneself. They are the underlying roots of everyone's behavior. Then we can look at ourselves a little more realistically, namely not blaming ourselves for the unwholesome roots, not patting ourselves on the back for the wholesome ones, but rather accepting their existence within us. We can also accept others more clearsightedly and have a much easier time relating to them.

People generally try to show themselves off as something better than they really are. Then, of course, they become disappointed in themselves when they fail, and

equally disappointed in others. To realistically know oneself makes it possible to truly love. That kind of feeling gives the light-heartedness to this job in which we're engaged, which is needed. By accepting ourselves and others as we truly are, our job of purification, chipping away at the defilements, is made much easier.

Our own mind can make us happy, our own mind can make us unhappy. There is no person or thing in the whole world that will do this for us. All happenings act as triggers for us, which constantly catch us unawares. Therefore we need to develop strong awareness of our own mind-moments.

If we can achieve some calm, that indicates that concentration is improving. But unless that valuable skill is used for insight, it's a waste of time. If the mind becomes calm, joy often arises, but we must observe how fleeting and impermanent that joy is, and how even bliss is essentially still only a condition which can be easily lost. Only insight is irreversible.

Impermanence (anicca) needs to be seen quite clearly in everything that happens, whether it is in or out of meditation. The fact of constant change should and must be used for gaining insight into reality.

The more we watch our mind and see what it does to us and for us, the more we will be inclined to take good care of it and treat it with respect. One of the biggest mistakes we can make is taking the mind for granted. The mind has the capacity to create good and also evil for us, and only when we are able to remain happy and even-minded no matter what conditions are arising, only then can we say that we have gained a little control. Until then we are out of control and our thoughts are our master.

"Mindful" is being fully absorbed in the moment, leaving no room for anything else. We are filled with the momentary happening, whether that may be standing or sitting or lying down, being comfortable or uncomfortable, feeling pleasant or unpleasant. Whichever it may be, it is a non-judgmental awareness, "knowing only," without evaluation.

When we watch mind-moments arising, staying and ceasing, detachment from our thinking process will result, which brings dispassion. Thoughts are coming and going

all the time, just like the breath. If we hang on to them, try to keep them, that's when all the trouble starts. We want to own them and really do something with them, especially of they are negative, which is bound to create dukkha.

Dukkha is self-made and self-perpetuated. If we are sincere in wanting to get rid of it, we have to watch the mind carefully, to get an insight into what's really happening within. What is triggering us? There are innumerable triggers, but there are only two reactions. One is equanimity and one is craving.

The more we experience every moment as worthwhile, the more energy there is. There are no useless moments, every single one is important, if we use it skillfully. Enormous energy arises from that, because all of it adds up to a life which is lived in the best possible way.

Being happy also means being peaceful, but quite often people don't really want to direct their attention to that. There is the connotation of "not interesting" about it, or "not enough happening."

If we really want peace, we have to be nobody. Neither important, nor clever, nor beautiful, nor famous, nor right, nor in charge of anything. We need to be unobtrusive and with as few attributes as possible.

To be nobody doesn't mean never to do anything again. It just means to act without self-display and without craving for results.

It seems to be so much more ingrained in us and so much more important to be "somebody," than to have peace. So we need to inquire with great care what we are truly looking for. What is it that we want out of life? If we want to be important, appreciated, loved, then we have to take their opposites in stride also. Every positive brings with it a negative, just as the sun throws shadows. If we want one, we must accept the other, without moaning about it.

But if we really want a peaceful heart and mind, inner security and solidity, then we have to give up wanting to be somebody, anybody at all. Body and mind will not disappear because of that, what disappears is the urge and the reaching out and the affirmation of the importance and supremacy of this particular person, called "me."

Wanting to be somebody is dangerous. It's like playing with a burning fire into which one puts one's hands all the time and it hurts constantly. Nobody will play that game according to our own rules. People who really manage to be somebody, like heads of state, invariably need a solid bodyguard around them because they are in danger of their lives. Nobody likes to admit that someone else is more important. One of the major deterrents to peace of mind is the "somebody" of our own creation.

In the world we live in, we can find people, animals, nature and man-made things. Within all that, if we want to be in charge of anything, the only thing we have any jurisdiction over, is our own heart and mind. If we really want to be somebody, we could try to be that rare person, the one who is in charge of his own heart and mind. To be somebody like that is not only very rare, but also brings with it the most beneficial results. Such a person does not fall into the trap of the defilements. Although the defilements may not be uprooted yet, he won't commit the error of displaying them and getting involved with them.

It seems negative and depressing to be nobody and have nothing. We have to find out for ourselves that it is the most exhilarating and liberating feeling we can ever have.

Nobody wants to be the first one without weapons; others might win. Does it really matter?

We're attached to the things, people, ideas and views, which we consider ours and believe to be right and useful. These attachments will keep us from getting in touch with absolute truth.

Whether we find anything within us which is pure, desirable, commendable or whether it's impure and unpleasant, makes no difference. All mental states owned and cherished keep us in duality, where we are hanging in mid-air, feeling very insecure. They cannot bring an end to suffering. One moment all might be well in our world and we love everyone, but five minutes later we might react with hate and rejection.

In order to have direct knowledge, it's as if we were a weight and must not be tied to anything, so that we can sink down to the bottom of all the obstructions, to see the truth shining through. The tool for that is a powerful mind, a weighty mind. As long as the mind is interested in petty concerns, it doesn't have the weightiness that can bring it to the depth of understanding.

For most of us, our mind is not in the heavy-weight class, but more akin to bantam weight. The punch of a heavy-weight really accomplishes something, that of a bantam weight is not too meaningful. The light-weight mind is attached here and there to people and their opinions, to one's own opinions, to the whole duality of pure and impure, right and wrong.

The deepest truth that the Buddha taught was that there is no individual person. This has to be accepted and experienced at a feeling level. As long as one hasn't let go of owning body and mind, one cannot accept that one isn't really this person.

Having had an experience of letting go, even just once, proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that it means getting rid of a great burden. Carrying one's hate and greed around is a heavy load, which, when abandoned, gets us out of the duality of judgment. It's pleasant to be without thinking; mental formations are troublesome.

If we succeed even once or twice during a day to let go of our reactions, we have taken a great step and can more easily do it again. We have realized that a feeling which has arisen can be stopped, it need not be carried around all day. The relief from this will be the proof that a great inner discovery has been made and that the simplicity of non-duality shows us the way towards truth.

In order to embrace the spiritual path fully, be able to grow on it and walk along it with a feeling of security, one has to renounce. Renunciation doesn't necessarily mean cutting off one's hair or wearing robes. Renunciation means letting go of all ideas and hopes that the mind would like to grasp and retain, be interested in and wants to investigate. The mind wants to have more of whatever is available. If it can't get more, then it makes up fantasies and imaginings and projects them upon the world. That will never bring true satisfaction, inner peace, which can only be won by renunciation.

The world glitters and promises so much, but never, never keeps its promises. Everyone has tried a number of its temptations and not one of them has really been fulfilling. The real fulfillment, the completeness of peace, lacking nothing, the totality of being at ease and not wanting anything, cannot be fulfilled in the world. There's nothing that can fill one's wants utterly and completely. Money, material possessions, another person, some of these can do so. And yet there's that niggling doubt: "Maybe I'll find something else, more comfortable, easier, not so demanding and above all something new." Always that which is new promises fulfillment.

http://archive.thebuddhadharma.com/issues/2003/spring/ayya_khema_facing_mirror.html

So criticism is not helpfulbut acknowledgement is. If, for example, we notice someone being unmindful, the right response would be, I wonder how mindful I am at the moment? This is the only worthwhile response. If we observe something unskillful in someone and want to criticize, we should remind ourselves that criticism is harmful to us.

By the time repeated criticism becomes a habit, we have carved ruts of negativity within ourselves. We probably all know someone who habitually criticizes, and we know how unpleasant it is to listen to them. Consequently, we must be on our guard against criticism, and avoid inflicting such an unpleasant habit on others. We should also be aware that every time we criticize we are gradually forming a habit.

Conversely, if we take the opportunity to observe what is going on in the other person, we can make use of what we notice in their behavior as a kind of mirror on ourselves. This is a very valuable mirror, because although it may not give us a view of our physical features, it does enable us to embark upon the much more difficult task of knowing ourselves. The task is difficult because not only do we lack awareness, but we prefer it that waywe prefer not to know the truth; we are anxious to avoid it because we fear it will be unpleasant.

Preoccupying ourselves with winning praise and avoiding blame is obviously a little absurd, but we don't really question it. In addition, this preoccupation underlies our reluctance to take up any kind of self-analysis: we are afraid to find out things about ourselves for which we might have to accept blame. We prefer to wear blinkers and avoid an all-round look at ourselves. The fear of blame may be dealt with using the formula, Acknowledge, don't blame, change. The first step is to become aware of this fear of being rebuked, and of disagreement, and lack of support and appreciation. The fear of blame is the same as our fear of death, or our fear on behalf of our ego, our selfaffirmation. Ultimately, it is the fear of not being here any more. Of course, when we anticipate blame, we are not afraid of actually disappearing on the spot; we are afraid of the disappearance of our self-esteem, which depends on the appreciation of others.

In our quest for affirmation from others we make ourselves the slaves of our environment. So long as this environment fails to match our expectations, or to confirm how wonderful, intelligent, or beautiful we are, we will continue to be uncomfortable. Such an attitude makes life enormously difficult, and obstructs our progress toward self-knowledge. Conversely, honest self-knowledge is essential in enabling us to let go, including letting go of our fear of blame. We can only let go of that which we have fully recognized for ourselves, and it is quite unnecessary to transform our fear of blame into fear of self-knowledge. The fact that we are able to let go of self after we have understood it doesn't mean that we die. It means that selfcenteredness is no longer the dominant force in our life. Things need not revolve around how we see them all the time. Instead, we open up a space within for that which is universally true. We then understand that because there are faults in every aspect of conditioned existence, nothing perfect is to be found anywhere. Just consider the fact of impermanence: all that has come into being must pass away, and nothing stays the same. If we try to hold on to an experience of something, it slips away like sand through our fingers. The fundamental unreliability of things can of course become an occasion for blame, especially when other people let us down by not keeping an appointment or not completing a job properly. No one would ever criticize a star in the sky when it becomes a supernova and fades awaywe know that it would be pointless to offer such a reproach, since it just happens. But in reality this is the true nature of all things, and it is equally pointless to complain about the unreliability of everything else in the universe. All conditioned things are imperfect. This is why it is worthwhile to look at ourselves without fear and to see what it is about other people that we don't like. Do we dislike their negativity? We should examine ourselves for negativity. Do we dislike their constant attention-seeking? Is it possible that we too have the same desire to be the center of attention? In this way, we will get to know ourselves better and better.

We should also remember that we are constantly changing. Our powers and capabilities can be seen to fluctuate from one moment to the next. This also applies in meditation. Sometimes the mind may focus very quickly; on other occasions it may have to clear away so many thoughts that an hour has elapsed before we attain a degree of stillness. We tend to refer this ability or inability back to our self and take it on as our own. But why do we feel the need to do this? What is really happening is that the mind is constantly changing.

If we can see how everything changes in ourselves, it is reasonable to conclude that the same goes for everyone else. If someone behaves in a way unworthy of praise, we should appreciate that they will change, hopefully for the better. So in becoming more aware of impermanence

especially impermanence of bad behaviorwe will find it easier to let go of nitpicking and the urge to find fault.

We are all born with six rootsthree good ones and three bad oneswhich is why it is pointless to condemn ourselves or others. The only response that makes any sense is to recognize these roots, and to commit ourselves to encouraging the good ones to flourish, so as to gradually attenuate the unwholesome ones.

The unwholesome roots are of course greed, hatred and delusion (delusion in the sense of egoillusion). But their opposites should be just as familiar to us. If we can see the three good roots generosity, unconditional love and wisdomin other people, we may draw the natural conclusion that they are also present within us. Actually, we do know perfectly well exactly when, where and how to practice. Words and precepts are never enough on their own, but we already have sufficient wisdom within us to sense the truth when we hear it, and to know where it can be found.

Obviously we are looking for happiness and peace, just like everyone else is doing. Sceptical doubt, that alarmist, says: "I'm sure if I just handled it a little cleverer than I did last time I'll be happy. There are a few things I haven't tried yet." Maybe we haven't flown our own plane yet, or lived in a cave in the Himalayas or sailed around the world, or written that best-selling novel. All of these are splendid things to do in the world except they are a waste of time and energy.

Sceptical doubt makes itself felt when one isn't quite sure what one's next move should be. "Where am I going, what am I to do?" One hasn't found a direction yet. Sceptical doubt is the fetter in the mind when the clarity which comes from a path moment is absent. The consciousness arising at that time removes all doubt, because one has experienced the proof oneself. When we bite into the mango, we know its taste.

http://www.buddhanet.net/ayyatalk.htm

The Buddha spoke about two kinds of people, the ordinary worldling (puthujjana) and the noble person (ariya). Obviously it is a worthwhile ambition to become a noble person, but if we keep looking for it at some future time, then it will escape us. The difference between a noble one and a worldling is the experience of "path and fruit" (magga-phala). The first moment of this supermundane

consciousness is termed Stream-entry (sotapatti) and the person who experiences it is a Streamwinner (sotapanna). If we put that into our mind as a goal in the future, it will not come about, because we are not using all our energy and strength to recognise each moment. Only in the recognition of each moment can a path moment occur. The distinguishing factor between a worldling and a noble one is the elimination of the first three fetters binding us to continuous existence. These three, obstructing the worldling, are: wrong view of self, sceptical doubt and belief in rites and rituals, (sakkayaditthi, vicikiccha and silabbatta-paramasa). Anyone who is not a Stream-winner is chained to these three wrong beliefs and reactions that lead away from freedom into bondage. Let's take a look at sceptical doubt first. It's that niggling thought in the back of the mind: "There must be an easier way," or "I'm sure I can find happiness somewhere in this wide world." As long as there's doubt that the path of liberation leads out of the world, and the belief is there that satisfaction can be found within the world, there is no chance of noble attainment, because one is looking in the wrong direction. Within this world with its people and things, animals and possessions, scenery and sense contacts, there is nothing to be found other than that which we already know. If there were more, why isn't it easily discernible, why haven't we found it? It should be quite plain to see. What are we looking for then? Obviously we are looking for happiness and peace, just like everyone else is doing. Sceptical doubt, that alarmist, says: "I'm sure if I just handled it a little cleverer than I did last time I'll be happy. There are a few things I haven't tried yet." Maybe we haven't flown our own plane yet, or lived in a cave in the Himalayas or sailed around the world, or written that best-selling novel. All of these are splendid things to do in the world except they are a waste of time and energy. Sceptical doubt makes itself felt when one isn't quite sure what one's next move should be. "Where am I going, what am I to do?" One hasn't found a direction yet. Sceptical doubt is the fetter in the mind when the clarity which comes from a path moment is absent. The consciousness arising at that time removes all doubt, because one has experienced the proof oneself. When we bite into the mango, we know its taste.

The wrong view of self is the most damaging fetter that besets the ordinary person. It contains the deeply imbedded "this is me" notion. Maybe it's not even "my" body, but there is "someone" who is meditating. This "someone" wants to get enlightened, wants to become a Stream-winner, wants to be happy. This wrong view of self is the cause of all problems that could possibly arise.

As long as there's "somebody" there, that person can have problems. When there's nobody there, who could have difficulties? Wrong view of self is the root which generates all subsequent pain, grief and lamentation. With it also come the fears and worries: "Am I going to be alright, happy, peaceful, find what I am looking for, get what I want, be healthy, wealthy and wise?" These worries and fears are well substantiated from one's own past. One hasn't always been healthy, wealthy and wise, nor gotten what one wanted, nor felt wonderful. So there's very good reason to be worried and fearful as long as wrong view of self prevails.

Rites and rituals are brought to an interesting end because the person who has experienced a path moment will under no circumstance indulge in any role-playing. All roles are the ingredients of unreality. One may continue religious rites, because they contain aspects of respect, gratitude and devotion. But there will not be any rituals in how to relate to people or to situations or how to invent stories about oneself because the response is with a spontaneous open heart.

Letting go of the wrong view of self is -of course - the most profound change, causing all other changes. For the Stream-winner the wrong view of self can never intellectually arise again, but feeling-wise it can, because the path moment has been so fleeting. It hasn't made the complete impact yet. If it had done so, it would have resulted in Enlightenment. This is possible and is mentioned in the Buddha's discourses as having happened during his lifetime. All four stages of holiness were realised while listening to the Dhamma.

The view we have of ourselves is our worst enemy. Everyone has made up a persona, a mask that one wears and we don't want to see what's behind it. We don't allow anyone else to look either. After having had a path moment, that is no longer possible. But the mask, fear and rejection come to the fore. The best antidote is to remember again and again, that there's really nobody there, only phenomena, nothing more. Even though the inner vision may not be concrete enough to substantiate such a claim, the affirmation helps to loosen the grasping and clinging and to hang on a little less tightly.

When people hear or read about Nibbana, they are apt to say: "How can I want nothing?" When one has seen that everything one can possibly want is meant to fill an inner void and dissatisfaction, then the time has come to want nothing. This goes beyond "not wanting" because one now accepts the reality that there is nothing worthwhile to be had. Not wanting anything will make it possible to experience that there is actually nothing only peace and quiet.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/khema/bl095.html

Yet in order to experience no-self, one has first to fully know self. Actually know it. But unless we do know what this self is, this self called "me," it is impossible to know what is meant by "there is no self there." In order to give something away, we have to first fully have it in hand.

We are constantly trying to reaffirm self. Which already shows that this "self" is a very fragile and rather wispy sort of affair, because if it weren't why would we constantly have to reaffirm it? Why are we constantly afraid of the "self" being threatened of its being insecure, of its not getting what it needs for survival? If it were such a solid entity as we believe it to be, we would not feel threatened so often.

Now the blame that is levied at us is not the problem. The problem is our reaction. The problem is that we feel smaller. The ego has a hard time reasserting itself. So what we usually do is we blame back, making the other's ego a bit smaller too.

Identification with whatever it is that we do and whatever it is that we have, be it possessions or people, is, so we believe, needed for our survival. "Self" survival. If we don't identify with this or that, we feel as if we are in limbo. This is the reason why it is difficult to stop thinking in meditation. Because without thinking there would be no identification. If I don't think, what do I identify with? It is difficult to come to a stage in meditation in which there is actually nothing to identify with any more.

Lord Buddha compared listeners to four different kinds of clay vessels. The first clay vessel is one that has holes at the bottom. If you pour water into it, it runs right out. In other words, whatever you teach that person is useless. The second clay vessel he compared to one that had cracks in it. If you pour water into it, the water seeps out. These people cannot remember. Cannot put two and two together. Cracks in the understanding. The third listener he compared to a vessel that was completely full. Water cannot be poured in for it's full to the brim. Such a person, so full of views he can't learn anything new! But hopefully, we are the fourth kind. The empty vessels without any holes or cracks. Completely empty. Whatever we think reality is, it surely is not, because if it were, we would never be unhappy for a single moment. We would never feel a lack of anything. We would never feel a lack of companionship, of ownership. We would never feel frustrated, bored. If we ever do, whatever we think is real, is not. What is truly reality is completely fulfilling. If we aren't completely fulfilled, we aren't seeing complete reality. So, any view that we may have is either wrong or it is partial.

Any identification, any possession that is clung to, is what stops us from reaching transcendental reality. Now we can easily see this clinging when we cling to things and people, but we cannot easily see why the five khandhas are called the five clung-to aggregates. That is their name, and they are, in fact, what we cling to most. That is an entire clinging. We don't even stop to consider when we look at our body, and when we look at our mind, or when we look at feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness vedana, saa, sankhara, and viana. We look at this mind-and-body, nama-rupa, and we don't even doubt the fact that this is my feeling, my perception, my memory, my thoughts, and my awareness of my consciousness. And no one starts doubting until they start seeing. And for that seeing we need a fair bit of empty space apart from views and opinions.

There is nothing that is secure. Nothing to hold on to, nothing that is stable. The whole universe is constantly falling apart and coming back together. And that includes the mind and the body which we call "I." You may believe it or not, it makes no difference. In order to know it, you must experience it; when you experience it, it's perfectly clear. What one experiences is totally clear. No

one can say it is not. They may try, but their objections make no sense because you have experienced it.

An ordinary mind can only know ordinary concepts and ideas. If one wants to understand and experience extraordinary experiences and ideas, one has to have an extraordinary mind. An extraordinary mind comes about through concentration. Most meditators have experienced some stage that is different then the one they are use to. So it is not ordinary any more. But we have to fortify that far more than just the beginning stage. To the point where the mind is truly extraordinary. Extraordinary in the sense that it can direct itself to where it wants to go. Extraordinary in the sense that it no longer gets perturbed by everyday events. And when the mind can concentrate, then it experiences states which it has never known before. To realize that your universe constantly falls apart and comes back together again is a meditative experience. It takes practice, perseverance and patience. And when the mind is unperturbed and still, equanimity, evenmindedness, peacefulness arise.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Pointers: What You Will Find When Investigating Who You AreD'EverandPointers: What You Will Find When Investigating Who You ArePas encore d'évaluation

- Karma, Mind, and Quest for Happiness: The Concrete and Accurate Science of Infinite TruthD'EverandKarma, Mind, and Quest for Happiness: The Concrete and Accurate Science of Infinite TruthPas encore d'évaluation

- Pure Land Buddhism - Dialogues With Ancient MastersD'EverandPure Land Buddhism - Dialogues With Ancient MastersPas encore d'évaluation

- Consciousness - My Ultimate Reality: An Intimate Self-InquiryD'EverandConsciousness - My Ultimate Reality: An Intimate Self-InquiryPas encore d'évaluation

- Available Truth: Excursions into Buddhist Wisdom and the Natural WorldD'EverandAvailable Truth: Excursions into Buddhist Wisdom and the Natural WorldPas encore d'évaluation

- The Nature of Things: Navigating Everyday Life with GraceD'EverandThe Nature of Things: Navigating Everyday Life with GracePas encore d'évaluation

- The Five-Minute Buddhist Meditates: The Five-Minute Buddhist, #2D'EverandThe Five-Minute Buddhist Meditates: The Five-Minute Buddhist, #2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Condensed Wisdom of Herb Fitch Volume Two: The Golden Circle of the SoulD'EverandCondensed Wisdom of Herb Fitch Volume Two: The Golden Circle of the SoulPas encore d'évaluation

- Condensed Wisdom of Herb Fitch Volume Three: Letters to Faithful WitnessesD'EverandCondensed Wisdom of Herb Fitch Volume Three: Letters to Faithful WitnessesPas encore d'évaluation

- Like A Large Immovable Rock: Letters From Disciples Of A Modern SageD'EverandLike A Large Immovable Rock: Letters From Disciples Of A Modern SagePas encore d'évaluation

- ENLIGHTENMENT: May or May Not Happen: Enlightenment Series, #2D'EverandENLIGHTENMENT: May or May Not Happen: Enlightenment Series, #2Évaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Autobiography of Gnani Purush Dadashri: Gnani Purush DadashriD'EverandAutobiography of Gnani Purush Dadashri: Gnani Purush DadashriPas encore d'évaluation

- Being Nothing: What is there to seek if the one seeking does not exist?D'EverandBeing Nothing: What is there to seek if the one seeking does not exist?Pas encore d'évaluation

- U. G. Krishnamurti: Collected Works: The Mystique of Enlightenment, Courage to Stand Alone, Mind is a Myth, The Natural StateD'EverandU. G. Krishnamurti: Collected Works: The Mystique of Enlightenment, Courage to Stand Alone, Mind is a Myth, The Natural StatePas encore d'évaluation

- The Oneness of the Eastern Heart and the Western MindD'EverandThe Oneness of the Eastern Heart and the Western MindÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- The Heart Meditation: The Modern Meditator’s Simple Meditations for Beginners Series, #1D'EverandThe Heart Meditation: The Modern Meditator’s Simple Meditations for Beginners Series, #1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Enlightened: Buddha's Philosophy and Meditation PracticesD'EverandEnlightened: Buddha's Philosophy and Meditation PracticesPas encore d'évaluation

- What Makes You Thinking You Are a Meditation Practitioner?D'EverandWhat Makes You Thinking You Are a Meditation Practitioner?Pas encore d'évaluation

- Spiritual Game - KIRAN BABA On the Holy Business of EnlightenmentD'EverandSpiritual Game - KIRAN BABA On the Holy Business of EnlightenmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Enlightenment Who Cares! (A seeker's quest for Enlightenment with Ramesh S. Balsekar): Enlightenment Series, #3D'EverandEnlightenment Who Cares! (A seeker's quest for Enlightenment with Ramesh S. Balsekar): Enlightenment Series, #3Évaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- The Art of LivingDocument4 pagesThe Art of LivingTertBKRRRPas encore d'évaluation

- Words of Wisdom - Webu SayadawDocument3 pagesWords of Wisdom - Webu SayadawDhamma ThoughtPas encore d'évaluation

- No Practice Is Needed Papaji PDFDocument3 pagesNo Practice Is Needed Papaji PDFSurjeet Singh SaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Maha Boowa QuotesDocument27 pagesMaha Boowa QuotesCalvin Sweatsa LotPas encore d'évaluation

- TSUTRIM GYAMTSO. Biography PDFDocument5 pagesTSUTRIM GYAMTSO. Biography PDFadikarmikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Q and A On VipassanaDocument4 pagesQ and A On VipassanaCalvin Sweatsa LotPas encore d'évaluation

- Pema Chodron QuotesDocument184 pagesPema Chodron QuotesCalvin Sweatsa Lot100% (6)

- Abhidhamma Survey of Paramattha DhammasDocument292 pagesAbhidhamma Survey of Paramattha DhammasCalvin Sweatsa LotPas encore d'évaluation

- Abhidhamma Chart Cetasika Mental FactorsDocument2 pagesAbhidhamma Chart Cetasika Mental FactorsCalvin Sweatsa Lot0% (1)

- Chogyam Trungpa QuotesDocument12 pagesChogyam Trungpa QuotesCalvin Sweatsa LotPas encore d'évaluation

- Pai Da and La Jin Self Healing Therapy Handbook1Document34 pagesPai Da and La Jin Self Healing Therapy Handbook1Calvin Sweatsa Lot100% (5)

- Metric Schnorr Lock Washer SpecDocument3 pagesMetric Schnorr Lock Washer SpecGatito FelinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Do We Hate Hypocrites - Evidence For A Theory of False SignalingDocument13 pagesWhy Do We Hate Hypocrites - Evidence For A Theory of False SignalingMusic For youPas encore d'évaluation

- 2007 - Q1 NewsletterDocument20 pages2007 - Q1 NewsletterKisara YatiyawelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Trust Is The Coin of The Realm by George P. ShultzDocument13 pagesTrust Is The Coin of The Realm by George P. ShultzHoover Institution100% (2)

- Skills For Developing Yourself As A LeaderDocument26 pagesSkills For Developing Yourself As A LeaderhIgh QuaLIty SVTPas encore d'évaluation

- Electrical Information: Service Training MechanikDocument22 pagesElectrical Information: Service Training Mechanikfroilan ochoaPas encore d'évaluation

- ComeniusDocument38 pagesComeniusDora ElenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Subiecte Engleza August 2018 - V1Document6 pagesSubiecte Engleza August 2018 - V1DenisPas encore d'évaluation

- SDS SheetDocument8 pagesSDS SheetΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣΠΑΝΑΓΟΣPas encore d'évaluation

- AZ-300 - Azure Solutions Architect TechnologiesDocument3 pagesAZ-300 - Azure Solutions Architect TechnologiesAmar Singh100% (1)

- EikonTouch 710 ReaderDocument2 pagesEikonTouch 710 ReaderShayan ButtPas encore d'évaluation

- Project RealDocument4 pagesProject RealKenneth Jay BagandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hayat e Imam Abu Hanifa by Sheikh Muhammad Abu ZohraDocument383 pagesHayat e Imam Abu Hanifa by Sheikh Muhammad Abu ZohraShahood AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Labor Law Review Questions and AnswersDocument151 pagesLabor Law Review Questions and AnswersCarty MarianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Fabric Data Science 1 150Document150 pagesFabric Data Science 1 150pascalburumePas encore d'évaluation

- Sand Casting Lit ReDocument77 pagesSand Casting Lit ReIxora MyPas encore d'évaluation

- NIA Foundation PLI Proposal Template (Repaired)Document23 pagesNIA Foundation PLI Proposal Template (Repaired)lama dasuPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Finite Element Model of Tsing Ma Bridge For Structural Health MonitoringDocument32 pagesAdvanced Finite Element Model of Tsing Ma Bridge For Structural Health MonitoringZhang ChaodongPas encore d'évaluation

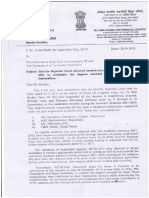

- Notification On Deemed Examination Result NoticeDocument2 pagesNotification On Deemed Examination Result Noticesteelage11Pas encore d'évaluation

- IndexDocument3 pagesIndexBrunaJ.MellerPas encore d'évaluation

- Longman Communication 3000Document37 pagesLongman Communication 3000irfanece100% (5)

- Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility in IndiaDocument12 pagesEvolution of Corporate Social Responsibility in IndiaVinay VinuPas encore d'évaluation

- AVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDocument16 pagesAVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDejan MitreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Monkey Shine - ScriptDocument4 pagesMonkey Shine - Scriptapi-583045984Pas encore d'évaluation

- Amnesty - Protest SongsDocument14 pagesAmnesty - Protest Songsimusician2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cosmology NotesDocument22 pagesCosmology NotesSaint Benedict Center100% (1)

- Brief Orientation To Counseling 1st Edition Neukrug Test BankDocument25 pagesBrief Orientation To Counseling 1st Edition Neukrug Test BankStevenAdkinsyjmd100% (55)

- Movie Review TemplateDocument9 pagesMovie Review Templatehimanshu shuklaPas encore d'évaluation

- Antennas and Wave Propagation: Subject Code: Regulations: R16 JNTUH Class:III Year B.Tech ECE II SemesterDocument18 pagesAntennas and Wave Propagation: Subject Code: Regulations: R16 JNTUH Class:III Year B.Tech ECE II SemesterSriPas encore d'évaluation

- Who Should Take Cholesterol-Lowering StatinsDocument6 pagesWho Should Take Cholesterol-Lowering StatinsStill RagePas encore d'évaluation