Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Effects of Achievement Goals On Emotions and Performance in Covariables PDF

Transféré par

Heinger Argüello HernándezDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Effects of Achievement Goals On Emotions and Performance in Covariables PDF

Transféré par

Heinger Argüello HernándezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

The Effects of Achievement Goals on Emotions and Performance in a Competitive Agility Task

Andrew J. Dewar, Maria Kavussanu, and Christopher Ring Online First Publication, May 6, 2013. doi: 10.1037/a0032291

CITATION Dewar, A. J., Kavussanu, M., & Ring, C. (2013, May 6). The Effects of Achievement Goals on Emotions and Performance in a Competitive Agility Task. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0032291

Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 2013, Vol. 2, No. 2, 000

2013 American Psychological Association 2157-3905/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0032291

The Effects of Achievement Goals on Emotions and Performance in a Competitive Agility Task

Andrew J. Dewar, Maria Kavussanu, and Christopher Ring

University of Birmingham The link between achievement goals and emotions has received much attention in the sport psychology literature. However, experimental studies are lacking. In this experiment, we investigated the effects of achievement goals on (a) emotions experienced before and after a competitive agility task and (b) perceived and actual agility performance. Male (n 60) and female (n 60) undergraduate students were assigned to a task, ego, or control group and following a practice session, they competed in a speed agility quickness ladder drill. Participants completed questionnaires measuring excitement and anxiety at prepractice and precompetition, happiness and dejection at postpractice and postcompetition, and perceived performance for practice and competition. Actual performance was also measured. ANCOVAs controlling for pre- and postpractice emotions and LSD comparisons showed that the ego group reported greater precompetition excitement than the task and control groups and higher precompetition anxiety than the task group. The task and ego groups also reported higher postcompetition perceived performance than the control group. The results suggest that ego involvement could inuence excitement, and both achievement goals could affect perceived performance. Keywords: goal involvement, experiment, excitement, anxiety, perceived performance

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

For over two decades, Achievement Goal Theory (Ames, 1992; Nicholls, 1989) has helped our understanding of achievement motivation in sport. A basic premise of this theory is that individuals seek to develop or demonstrate competence when participating in achievement contexts, such as sport. However, two conceptions of competence or ability exist. The rst is the undifferentiated conception of ability, where individuals do not differentiate effort from ability and more effort indicates higher ability. When using this conception, individuals view competence as effortful accomplishment. The second is the differentiated conception of ability, where ef-

Andrew J. Dewar, Maria Kavussanu, and Christopher Ring, School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom. We thank Faye Hamp, Sam Clixby, Tom Haines, and Victoria Fleming for their assistance with data collection. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Andrew J. Dewar, School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom. E-mail: a.j.dewar@bham.ac.uk 1

fort and ability are differentiated from each other, and ability is construed as capacity. When this conception of ability is used, individuals demonstrate ability when they perform as well as others with less effort or outperform others while exerting equal effort (Nicholls, 1984, 1989). The two conceptions of ability are embedded within two achievement goals: task and ego involvement. When individuals are task involved, they use self-referenced criteria to evaluate competence and feel successful when they improve or master a task. When they are ego involved, individuals use other-referenced criteria to evaluate competence and feel successful when they demonstrate superiority over others. Task and ego involvement refer to the states individuals experience at a certain point in time, whereas the proneness to be task and ego involved is known as task and ego orientation (Nicholls, 1984, 1989). Achievement goal orientations have been differentially related to a variety of outcomes in sport, such as positive and negative affect, persistence in practice, moral functioning, and perceived competence (Biddle, Wang, Kavussanu, & Spray, 2003).

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

Achievement Goals and Emotions Although achievement goal orientations have been examined in relation to a number of outcomes (Biddle et al., 2003), the effect of goal involvement on emotions experienced before and after competition has received little attention. Achievement goals could be associated with emotions because task and ego involvement are assumed to inuence the subjective experience of the situation (Nicholls, 1984). Specically, if there is opportunity for improvement and development of ones ability by exerting effort, task-involved individuals should nd an activity intrinsically satisfying (Nicholls, 1989), so they may experience more positive and less negative emotions. Excitement, which is a positive emotion that is linked with arousal and might be experienced when individuals in a challenging situation expect that they may reach a goal (Jones, Lane, Bray, Uphill, & Catlin, 2005), is often felt before competition and may be inuenced by achievement goals. Competition provides taskand ego-involved individuals with the opportunity to achieve their goal of improving or demonstrating high ability relative to others, respectively (Nicholls, 1984), which may lead to excitement. As yet, the effect of achievement goals on excitement before competition has received no research attention; instead, researchers have focused on the relationship between athletes goal orientations and positive and negative affective outcomes (for reviews see Biddle et al., 2003; Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999). Another emotion that may be inuenced by goal involvement, and is commonly reported before competition, is anxiety (e.g., Hall, Kerr, & Matthews, 1998; Vealey & Campbell, 1988), which reects uncertainty regarding goal attainment and coping (Lazarus, 2000) and is typied by feelings of apprehension and tension along with activation or arousal of the autonomic nervous system (Jones et al., 2005, p. 410). Indeed, uncertainty about the outcome of the competition and opponents ability may result in ego-involved athletes wondering whether they will achieve their goal of establishing superiority relative to others, thereby leading to anxiety. Task-involved athletes may expect that they will be able to make small improvements in their performance and, given that this is largely under their control, they should not

doubt their ability to achieve their goal of improving. Thus, ego involvement should be positively associated with anxiety and task involvement should be either inversely related or unrelated to anxiety. The link between achievement goals and anxiety in sport and physical education (PE) has been examined in several studies. In adolescent school pupils, somatic anxiety was higher during ego-involving than task-involving volleyball drills completed as part of a PE class (Papaioannou & Kouli, 1999). When measured 30 min prior to competition, cognitive anxiety was positively associated with ego involvement (Hall et al., 1998) and unrelated to task involvement in adolescent cross-country athletes; somatic anxiety was negatively related to task involvement in adolescent fencers (Hall & Kerr, 1997); and state anxiety was negatively associated with task orientation in adolescent gure skaters (Vealey & Campbell, 1988). Ego involvement and ego orientation were unrelated to anxiety in the latter two studies (Hall & Kerr, 1997; Vealey & Campbell, 1988). In general, the ndings regarding the relationship between achievement goals and anxiety experienced before competition are mixed. Importantly, researchers have not experimentally examined whether goal involvement affects anxiety experienced before a competitive task. Achievement goals might also be related to happiness, a positive emotion that is felt when an individual believes he or she has made progress toward a goal (Jones et al., 2005; Lazarus, 2000), and dejection, a low intensity negative emotion characterized by feelings of deciency and sadness (Jones et al., 2005, p. 411). The relationships between goal involvement and these emotions were investigatedretrospectivelyin male golfers during a competitive round of golf (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011): Results showed that task involvement was positively related to happiness and excitement and negatively linked to dejection. In team-sport athletes, task involvement during the match (as reported at the end of the match) was positively associated with happiness and negatively related to dejection experienced after the match (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2012). Ego involvement did not predict emotions in either study. Experimental research examining the effect of goal involvement on emotions or affect, particularly in a competitive setting, is scarce. An

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

exception is a study investigating the effect of task and ego involvement on positive and negative affect experienced by undergraduate students during a coordination task completed in a competitive environment (Standage, Duda, & Pensgaard, 2005). The two ego-involving groups reported experiencing negative affect more often than the two task-involving groups, but the groups did not differ in positive affect. In another experiment, mastery (i.e., task) and performance-approach (i.e., ego) participants showed no difference in enjoyment experienced during a noncompetitive golf-putting task (Kavussanu, Morris, & Ring, 2009). However, none of these experiments included a control group; thus, it is unclear whether the magnitude of the effects found for the task or ego groups were greater or less than those that would have been observed in a control group. To date, no experimental studies have investigated the effects of goal involvement on emotions experienced before or after a competitive task. Excitement and anxiety are felt because individuals evaluate whether they will attain a goal (Jones et al., 2005) and might be experienced before taking part in a competitive task. Moreover, happiness and dejection are felt when people judge whether they achieved a goal (Jones et al., 2005; Lazarus, 2000) and may be experienced when thinking about an activity they have completed successfully or unsuccessfully. Based on these conceptualisations of emotions (Jones et al., 2005; Lazarus, 2000), as well as previous research (e.g., Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011, 2012; Hall & Kerr, 1997), we expected that achievement goals would inuence excitement, anxiety, happiness, and dejection. Achievement Goals and Performance We investigated two types of performance: perceived and actual performance. Perceived performance, dened as ones own evaluations of how he or she has performed (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011), may be positively inuenced by task involvement. Task-involved individuals may be more conscious of small increments in performance, so they are more likely to perceive even minor improvements in performance as achievement (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011); thus, task involvement should lead to higher perceived performance. In contrast, due to their

focus on doing better than others, ego-involved athletes may overlook small improvements in their own performance, so they are unlikely to report high perceived performance when such improvements take place. In empirical research, task involvement was positively associated with perceived performance in golfers during a competition and in team sport athletes during a match (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011, 2012). In addition, task orientation was positively related to perceived performance in a match (Cervell, Rosa, Calvo, Jimenez, & Iglesias, 2007) and over the course of a season (van de Pol & Kavussanu, 2011) in tennis players. In these studies, ego involvement and orientation were unrelated to perceived performance. These results suggest that task involvement may be benecial for perceived performance in competitive sport situations. The effect of achievement goals on actual performance is less clear. A meta-analysis (Utman, 1997) that focused on academic tasks, such as anagrams, psychology exams, and reading comprehension, showed that learning goals (similar to task involvement) led to better performance than performance goals (similar to ego involvement). Also, school boys high in task orientation performed better on ve climbing walls of increasing difculty than boys high in ego orientation (Sarrazin, Roberts, Cury, Biddle, & Famose, 2002). However, there were no performance differences between mastery (task) and competitive (ego) groups on a oneon-one basketball shooting task (Giannini, Weinberg, & Jackson, 1988) or mastery and performance-approach groups on a golf-putting task (Kavussanu et al., 2009). Therefore, in sport settings, there is not consistent support for an effect of task and ego involvement on actual performance. A greater understanding of the relationships between goal involvement and actual performance may be achieved if a more precise measure of performance is used, for example, by taking into account errors made during the task. It is possible that the ego group may commit more errors than the task group because the former are focused on demonstrating superiority over others rather than performing the task as well as possible. Thus, research may benet from examining the effects of achievement goals on performance in such a task.

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

The Present Experiment Although researchers have examined the effect of achievement goals on affect experienced during a coordination task (Standage et al., 2005), and actual performance on academic tasks (e.g., Utman, 1997), the effects of goal involvement on emotions experienced before and after, or performance during, a competitive agility task have not been experimentally investigated. Doing so is important because it constitutes a step toward establishing whether goal involvement inuences emotions and performance. The present experiment had two purposes. The rst purpose was to investigate the effect of goal involvement on excitement and anxiety experienced before, and happiness and dejection felt after, a competitive agility task. We hypothesized that the task group would report higher excitement than the ego and control groups (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011); the ego group would report higher anxiety than the task and control groups (Hall et al., 1998; Papaioannou & Kouli, 1999); and the task group would report greater happiness and lower dejection than the ego and control groups (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2012). Our second purpose was to investigate the effect of goal involvement on perceived and actual performance. We expected that the task group would rate their performance higher (Cervell et al., 2007; Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011; van de Pol & Kavussanu, 2011) and perform better (Sarrazin et al., 2002) than the ego and control groups. Method Participants Male (n 60) and female (n 60) undergraduate students, with a mean age of 20.26 years (SD 1.56), completed a speed agility quickness ladder task as part of the experiment. On average, participants used speed agility quickness ladders once every 6 months (SD 1.95) and completed 3.41 hours (SD 4.72) of speed or agility training per month. Participants took part in rugby (20%), soccer (11.67%), American football (10.83%), hockey (7.5%), athletics (5%), netball (5%), tennis (4.17%), basketball (3.33%), dance (3.33%), kayaking (3.33%), cricket (2.5%), ski-racing (2.5%),

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

cross-country running (1.67%), golf (1.67%), gymnastics (1.67%), karate (1.67%), swimming (1.67%), Australian rules football, cycling, horse riding, korfball, rowing, short-track speed skating, squash, trampolining, triathlon, volleyball, and water polo (0.83% each), or indicated no main sport (3.33%). The highest level participants had competed at in their main sport was international (9%), national (11%), county (25%), regional (17%), and club (38%). Equipment and Experimental Task We used an XLR8 Flexible Rung Speed Ladder, which was 4.33 m long 45 cm wide with 10 40 cm 40 cm squares and 11 3 cm 40 cm rungs, and two marker cones, each placed 1 m from the edge of the last rung at each end of the ladder. The task was the Tango Drill (Davies, 2011), which was used because it allowed us to consider errors when measuring performance. Before starting this drill, participants stood behind the rst rung on the left side of the ladder. To begin, they placed their left foot into the rst square of the ladder, and then stepped outside to the opposite side of the ladder, with their right and then their left foot. This movement was repeated in the opposite direction, and the sequence was completed ve times until the participant reached the end of the ladder. Participants then ran around the marker cone, thus completing one repetition of the drill. One trial consisted of four repetitions of the drill. Experimental Design A mixed design was used in this experiment. The between-subjects factor was Group and had three levels: task, ego, and control. The withinsubjects factor was Time and had two levels, but these differed depending on the dependent variables: prepractice and precompetition for excitement and anxiety; postpractice and postcompetition for happiness and dejection; and practice and competition for perceived and actual performance. Given that the label for the levels of the Time factor differed depending on the outcome variable examined, we use the relevant terms (e.g., prepractice, precompetition) when referring to this factor.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

Manipulations The manipulations were based on previous research (Sage & Kavussanu, 2007; Standage et al., 2005) and are described below. The italics indicate words emphasized by the experimenters. Task group. The purpose of the task group manipulation was to get participants to use selfreferenced criteria to evaluate their competence. Therefore, we emphasized improving and mastering the task. Participants in this group were told: Research shows that people can improve their performance on this drill with practice. You will now have the opportunity to improve your own performance on the Tango Drill. Try to focus on doing the steps as well as you can, and try as hard as you can to improve your performance. The outcome of the competition is not that important. The important thing is that you do the steps as well as you can and that you try hard to improve your own performance. Similar to Kavussanu et al. (2009), each participant was given a manipulation prompt before every trial to reinforce the manipulation. In the task group, participants were told Try to focus on doing the steps as well as you can and try hard to improve your own performance. Ego group. The aim of the ego group manipulation was to get participants to use otherreferenced criteria to evaluate their competence. Therefore, performing well relative to their opponent was stressed. Also, to create a moderately difcult task, participants were told that we would make the competition fair by taking into account their level of ability; we expected this would engage all ego-involved participants. Indeed, ego-involved individuals with high perceived ability should prefer a moderately difcult task (Nicholls, 1984). Participants had not experienced repeated failures at the task, so those with low perceived ability may have not been convinced of their ability on the task; thus, they may also prefer a moderately difcult task (Nicholls, 1984). Participants were told: We will employ a handicap system that will create a fair competition. Research shows that some people have more natural sporting ability than others. You will now have the opportunity to show how good you are compared to others on the Tango Drill. Try to focus on beating your opponent and try to show that you are the best.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Improving performance is not that important. The important thing is that you win this competition and show that you have high natural sporting ability. The manipulation prompt in this group was Try to focus on beating your opponent and show that you have high natural sporting ability. Control group. The manipulation in this group contained information regarding the use of speed agility ladders, without any reference to improvement or performing well relative to others. Participants were told: Speed agility ladders are usually 4 m long and consist of a number of 40 cm squares. Ladder agility drills are used in many sports including rugby, football, hockey, netball, badminton, and American football. They are an integral part of many speed, agility, and quickness training programs. Speed agility ladders can be arranged in a number of formations and can be used for a wide variety of drills. The ladders are very durable and can last for up to 7 years. Before each trial, participants in the control group were told Speed agility ladders can be arranged in a number of formations and can be used for a wide variety of drills. Manipulation Check Some studies have examined the efcacy of the manipulation by asking participants about the purpose of (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996), or what was made salient during (Standage et al., 2005), the experiment. However, in line with Kavussanu et al. (2009), we asked participants to state in their own words what their goal was during the competition block, as this seemed a more accurate assessment of their goal state, which our manipulation aimed to elicit. Responses were coded as task (e.g., improve own score), ego (e.g., beat my opponent), both (e.g., to improve my own performance and to win over my opponent), or other (e.g., to not fall over) and were compared with the experimental group to which participants were assigned. Measures Emotions. We used the Sport Emotion Questionnaire (SEQ; Jones et al., 2005) to measure excitement and anxiety (prepractice, precom-

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

petition) and happiness and dejection (postpractice, postcompetition). In all cases, the stem was At this moment, I feel . . . Four items were used to measure excitement (e.g., energetic) and happiness (e.g., joyful), and ve items were used to assess anxiety (e.g., apprehensive) and dejection (e.g., sad). Participants responded to all items on a 5-point Likert scale, with anchors of not at all (1) and extremely (5). Allen, Jones, and Shefeld (2010) have reported construct validity and good reliability for the SEQ, with alpha coefcients ranging from .80 to .90 before, and .77 to .94 after, an experimental competition. In the present experiment, alpha coefcients for emotions assessed throughout the experiment ranged from .80 to .90. Means for all self-reported variables were computed and used in the analyses. Performance. We measured perceived and actual performance. For the former, a multi-item measure, based on a perceived improvement scale (Balaguer, Duda, & Crespo, 1999), was developed. The measure was designed to assess participants perceptions of how quickly and accurately they completed the task, as well as their overall performance on the task. This procedure is similar to that utilized by Van-Yperen and Duda (1999), who developed a measure of performance for use in soccer. Participants were asked to rate their performance over the last three trials and respond to the following items: I completed the drill quickly, I did the steps correctly, I changed direction quickly, I moved my feet quickly, I had good rhythm, I completed the drill accurately, and Overall, I performed optimally. Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert scale, with anchors of not at all true of me (1) and very true of me (7). The measure was administered at postpractice and postcompetition. Principal axis factor analysis revealed one factor, which explained 66.23% and 70.29% of the variance for the two conditions, respectively. Factor loadings ranged from .70 to .87 for postpractice, and .70 to .89 for postcompetition items. Internal consistency was high with Cronbachs alpha of .91 in practice and .92 in competition. Actual performance was assessed by the mean time, in seconds, it took participants to complete the three trials in each block. One of the experimenters started recording the time with a stopwatch when the participant put his or her foot in the rst square of the ladder and stopped timing when the participants rst foot exited the last square of the ladder on the nal

repetition. For every error participants committed (dened as an incorrect foot sequence or as touching the ladder and causing it to move), a 1-s penalty was added to their time for that trial. Procedure First, ethical approval was granted by the university research ethics committee. Then, the principal investigator and four research assistants recruited participants via an advertisement displayed on a notice board and an e-mail to all students enrolled in the School of Sport and Exercise Sciences. Both methods mentioned that course credit would be offered in return for participation in an experiment using speed agility ladders. Participants were recruited individually and then matched with an opponent of the same gender to avoid any effects on emotions and performance that could occur due to participating in competition with an opponent of the opposite gender; a similar procedure has been used in previous studies of competition (e.g., Cooke, Kavussanu, McIntyre, & Ring, 2011; Tauer & Harackiewicz, 2004). Individuals were assigned to pairs to reduce the possibility that participants were close friends; if that was the case, they may be more competitive than individuals who do not know each other (see Allen et al., 2010), which could contaminate the ndings. Pairs of participants were then pseudorandomly assigned to one of three groups (task, ego, control), that is, there was a constraint on randomisation, in that an equal number of males (n 20) and females (n 20) were allocated to each group. A random number grid, with values from 1 to 3 (representing the task, ego, and control groups, respectively), was used to create a sequence, and pairs of participants were assigned to the next available experimental group in this sequence.1 This method of group assignment is akin to random assignment without replacement and ensured that the experimenter did not select (so could not bias) the group to which participants were assigned. All participants were tested in pairs at the university running track. When the pair ar1 The sequence for group assignment was task, ego, control, ego, control, task, control, task, ego, control, ego, task, ego, task, control, task, control, ego, task, ego, control, ego, control, task, control, task, ego, control, ego, task.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

rived at the track, they read the information sheet, which informed them that they would complete a speed agility quickness ladder task a number of times and that questionnaires would be completed throughout the experiment. Questionnaires were administered at prepractice, postpractice, precompetition, and postcompetition. After reading the information sheet, participants completed an informed consent form, a general health questionnaire (no participants were excluded based on information provided in this questionnaire), and a demographics questionnaire. Next, they were told that they would perform the Tango Drill, which was explained and demonstrated to them, and they completed prepractice measures of excitement and anxiety experienced in relation to the upcoming task. Participants were then given the opportunity to walk through two repetitions of the drill to ensure they understood the movements and were given instruction by an experimenter if they were unsure or made a mistake. After checking understanding of the Tango Drill, an experimenter informed participants that they would practice the drill for three trials, that each trial consisted of four repetitions, and that they were to try and complete the task as fast as possible while making as few errors as possible. A practice block was completed to reduce quick-practice effects in the competition block; a similar procedure was followed by Jourden, Bandura, and Baneld (1991). Each block consisted of three trials because pilot testing revealed that actual performance in the competition block was stable after a three trial practice block.2 Participants were also told that a 1-s time penalty would be incurred for every error committed, and an error was dened. Participants completed each trial, one after the other3, with 3-min rest between trials; during this time, they watched the other participant complete the task or stood quietly. Their time to complete the trial was recorded, but participants were told that we were not interested in this information, and it was emphasized that this was a practice block. Participants were not allowed to practice between trials. Following the practice block, they completed the measure of perceived performance in practice, which referred to their

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

performance on these trials, and then they completed postpractice measures of happiness and dejection felt at that moment in relation to the last three trials. Participants were then informed that they would be competing against each other over three trials, after which they would receive feedback on their performance. The same manipulation was then delivered verbally to both participants, and precompetition excitement and anxiety, experienced at that moment in relation to the upcoming competition, were measured. Next, participants completed the three-trial competition block, and a manipulation prompt was given before each trial. After the competition block, participants completed the manipulation check and measures of perceived performance in competition, and postcompetition happiness and dejection, experienced at that moment in relation to the last three trials. Finally, they were given feedback regarding the outcome of the competition, completed a measure of task difculty (we did not examine this variable because there were no group differences), were debriefed, and thanked for their participation. At every testing session, there were two experimenters, who were matched to the gender of participants. The principal inves-

2 Two sets of pilot testing were carried out to determine the number of trials needed to reduce quick-practice effects and have similar actual performance times across the trials in the competition block. Results from the rst set, which included eight participants, showed a signicant decrease in actual performance between trial 1 and trials 2, 3, 4, and 5 (tested using 83.42% condence intervals [CI] because this value is similar to p-value of .05, see Julious, 2004). However, there were no other signicant differences between trials (Means for trials 1 to 5 were 33.62, CI [32.62, 34.62], 29.88, CI [28.68, 31.08], 28.79, CI [27.96, 29.61], 28.22, CI [27.25, 29.18], and 27.45, CI [26.53, 28.37], seconds, respectively). A second set of pilot testing, with data from 10 more individuals, revealed that after three practice trials (Means for trials 1 to 3, were 33.13, CI [29.64, 36.62], 30.83, CI [28.85, 32.80], 30.29, CI [26.61, 30.68], seconds, respectively), there were no signicant differences in actual performance between the trials in the competition block (Means for competition trials 1 to 3 were 28.65, CI [27.29, 30.00], 28.53, CI [27.29, 29.76], 28.44, CI [27.25, 29.62], seconds, respectively). 3 We conducted Group (task, ego, control) Gender (male, female) Order of Participation (rst, second) ANCOVAs, controlling for initial emotion or performance measure, and found no signicant effects of order of participation on any of the dependent variables.

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

tigator was also present during 90% of these sessions. Results Preliminary Analysis Prior to the main analysis, we conducted preliminary analyses. First, a check of missing values revealed that 0.01% of the data points were missing. Mean substitution, which involves replacing the missing values with the item mean, was used to replace these data points. Although there is some debate regarding the strengths and weaknesses of different methods for dealing with missing data (see Schafer & Graham, 2002), mean substitution was deemed an appropriate method to replace missing data because of the low percentage of missing values (Downey & King, 1998). Next, q q plots, histograms, and values of skewness and kurtosis were examined to investigate assumptions of one-way ANCOVA. The data satised these assumptions for all variables except dejection, for which we observed very low values (Practice M 1.15, Competition M 1.15). Dejection showed deviation from normality, which was not corrected by transforming the data, and therefore was excluded from the analyses. Also, one participant from the task group, one from the ego group, and two from the control group were excluded from the analysis because they had experience of the Tango Drill. Manipulation Check To investigate whether the experimental manipulation was successful, we examined the distribution of participants responses on the manipulation check across the three groups. Specically, we conducted a 3 Group (task, ego, control) 4 Response (task, ego, both, none) chi-square (2) test, 2(6) 35.76, p .001, which showed that the responses were not equally distributed among groups. Responses to the manipulation check, including participants responses classed as both, showed that 34 participants in the task group and 26 participants in the ego group reported a goal that was consistent with their assigned group. One participant from the control group had missing data on the manipulation check and was removed, which resulted in 37 participants in this group.

In the main analysis, we included only those participants who adhered to the manipulation (n 97 or 84% of eligible participants). This decision was based on previous research (Nadler & McDonnell, 2012; Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009), in which researchers have excluded participants based on the results of the Instructional Manipulation Check (IMC), a check used to determine whether participants read instructions carefully. In the rst of two studies, Oppenheimer et al. (2009) showed that analyzing data with only the participants who responded correctly to the IMC was superior to including all participants because a wellestablished experimental effect was revealed and there was increased power to detect this effect. In Study 2, participants who failed the IMC were not allowed to continue with the experiment until they passed this check. Results from the second study, which included all participants after they correctly completed the IMC, provided evidence of the well-established effect. Oppenheimer et al. (2009) suggested that the lack of an effect in the rst study was due to noisy data from those participants who did not engage with the task. Including only participants who respond correctly to the IMC reduced noise in the data (observed because participants did not follow instructions) and did not bias results (Oppenheimer et al., 2009). Although we did not use the IMC, our manipulation check examined whether participants adhered to the manipulation; thus, it shares some similarities to the IMC. Researchers have excluded participants who did not respond as expected to a manipulation (Ehrlenspiel, Wei, & Sternad, 2010; Stanger, Kavussanu, & Ring, 2012; Storbeck & Clore, 2005; Williams & DeSteno, 2008), and then investigated their research question with the remaining participants. The percentage of retained participants in our study (84%) is within the range of values observed from previous research (54%95%; Ehrlenspiel et al., 2010; Oppenheimer et al., 2009; Stanger et al., 2012; Williams & DeSteno, 2008). Main Analyses We investigated the effects of achievement goals on excitement, anxiety, happiness, and perceived and actual performance, using 3 Group (task, ego, control) Gender (male,

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

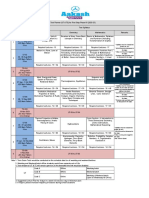

female) ANCOVAs. Gender was included in the analyses because previous research has revealed gender differences in goal orientation (e.g., Kavussanu & Roberts, 2001). In the ANCOVAs, we controlled for the relevant covariate: prepractice excitement and anxiety when examining group differences in precompetition excitement and anxiety, postpractice happiness when examining group differences in postcompetition happiness, and perceived and actual performance in practice when examining perceived and actual performance in competition. Signicant ANCOVAs were followed with least signicant difference (LSD) pairwise comparisons; effect size was represented with partial eta squared (2 p); and, based on recommendations by Kelley and Preacher (2012), 95% condence intervals for effect sizes are reported. Means and standard deviations for all dependent variables are shown in Table 1. ANCOVA revealed signicant group differences for precompetition excitement, F(2, 90) 5.97, p .004, 2 p .12, 95% CI [.02, .24]. LSD tests showed that the ego group experienced higher excitement than the task, p .004, 2 p .13, 95% CI [.02, .30], and control, p .002, 2 p .14, 95% CI [.03, .30], groups; the latter groups did not differ from each other, p .751, 2 p .00, 95% CI [.00,

.05]. These ndings can be seen in Figure 1A. There was also a gender effect, F(1, 90) 4.59, p .035, 2 p .05, 95% CI [.00, .16], showing that men felt more excited than women, but no group by gender interaction. The ANCOVA for precompetition anxiety, F(2, 90) 2.37, p .099, 2 p .05, 95% CI [.00, .15], revealed a marginally signicant effect. Based on the expected differences between task and ego groups (e.g., Papaioannou & Kouli, 1999), we interrogated this effect further. LSD tests showed that the ego group felt more anxiety than the task group, p .046, 2 p .06, 95% CI [.00, .21], and marginally more anxiety than the control group, p .069, 2 p .05, 95% CI [.00, .21], but the latter two groups did not differ, p .814, 2 p .00, 95% CI [.00, .06]. These results are presented in Figure 1B. There were no group effects on postcompetition happiness, F(2, 90) 0.09, p .917, 2 p .00, 95% CI [.00, .04]. The ANCOVA on perceived performance revealed a group effect, F(2, 90) 3.80, p .026, 2 p .08, 95% CI [.01, .19]. LSD tests showed that both the task, p .017, 2 p .09, 95% CI [.01, .23], and the ego, p .028, 2 p .07, 95% CI [.00, .22], groups perceived their performance to be better than the control group, but the task and ego groups did not differ in

Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations for Emotions and Performance in the Three Groups

Group Task M Excitement Prepractice Precompetition Anxiety Prepractice Precompetition Happiness Postpractice Postcompetition Perceived performance Practice Competition Actual performance Practice Competition 2.22 2.55a 2.02 1.92a 2.84 2.85 4.47 4.98a 35.37 31.34 SD 0.75 0.87 0.65 0.69 0.86 0.94 1.10 1.10 4.55 4.02 M 2.33 3.19ab 2.02 2.24a 2.76 2.72 4.52 4.99b 35.50 30.59 Ego SD 0.73 0.82 0.48 0.77 0.80 0.77 0.91 0.99 5.76 3.84 M 2.48 2.73b 2.12 2.02 3.02 3.02 4.67 4.71ab 34.96 31.36 Control SD 0.67 0.91 0.58 0.60 0.82 0.93 1.02 1.11 4.28 4.11

Note. Values with the same superscripts are signicantly different (p .05).

10

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

A

3.5

3.0

Excitement

b 2.5 a

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

2.0 1.0 Prepractice Time

Task Ego Control

Precompetition

B

2.5

2.0 c

Anxiety

b 1.5 Task Ego Control

1.0 Prepractice Time

Figure 1. Excitement (A) and Anxiety (B) of the three groups in prepractice and precompetition. In precompetition: a The ego group reported higher excitement than the task group; b the ego group reported higher excitement than the control group; c the ego group reported higher anxiety than the task group. The possible range of values for excitement and anxiety is 1 to 5.

Precompetition

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

11

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

perceived performance, p .997, 2 p .00, 95% CI [.00, .00]. These ndings can be seen in Figure 2. The ANCOVA on competition actual performance revealed no group effects, F(2, 90) 1.81, p .170, 2 p .04, 95% CI [.00, .13], but showed an effect for gender, F(1, 90) 15.84, p .001, 2 p .15, 95% CI [.05, .28], such that women took longer to complete the drill (i.e., performed worse) than men. There was no group by gender interaction for actual performance. Discussion To date, researchers have investigated the effect of achievement goals on affect experienced during a coordination task (Standage et al., 2005), as well as performance on experimental tasks (e.g., Utman, 1997). However, the effects of goal involvement on emotions before or after an agility task and on perceived performance during such a task have not been experimentally examined. This is important because it sheds light on the direction of these relationships. In the present study, we sought to ll this gap in the literature. Achievement Goals and Emotions Our rst study purpose was to examine whether achievement goals inuence excite-

ment and anxiety experienced before, and happiness and dejection felt after, a competitive agility task. Contrary to our hypothesis, precompetition excitement was greater in the ego than the task and control groups. This nding may be due to the handicap system implemented in the ego group, which might have led participants in this group to perceive the task as moderately difcult. Due to the nature of the task, ego-involved participants may have thought they had an equal chance of winning or losing and they might have believed that they could win the task; as a result, they experienced excitement (see Jones et al., 2005). Our result differs from Dewar and Kavussanus (2011) study, which showed that during a golf competition, task involvement was positively related to excitement, whereas ego involvement was unrelated to this variable. During competition, golfers may only be aware of how a few of many players are performing, so they may focus on improving and mastering the task, which could lead to excitement because task-involved athletes may have thought they might reach this goal (Jones et al., 2005). Another possible reason why the results for the current study are different to those reported by Dewar and Kavussanu (2011) is the different methods used. Specically, in the former, participants were completing an agility task in an

5.4 5.2

Perceived Performance

5.0 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 1.0 Practice

b b a a

Task Ego Control Competition

Time

Figure 2. Perceived performance of the three groups in practice and competition. a The task group perceived higher performance than the control group in competition; b the ego group perceived higher performance than the control group in competition. The possible range of values for perceived performance is 1 to 7.

12

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

experimental setting, whereas in the latter, athletes were involved in a competition at their local golf course. Thus, in the rst instance the setting was articial, whereas in the second it was natural, which may have affected the inuence of achievement goals on excitement. The effects of goal involvement on anxiety were not as strong as might have been expected. Specically, group differences in anxiety were small and marginally signicant. Anxiety was higher in the ego than the task group and marginally higher in the ego than the control group. These ndings support previous research (Papaioannou & Kouli, 1999), which showed that school pupils taking part in ego-involving volleyball drills had higher somatic anxiety than those in task-involving drills, and research reporting a positive relationship between ego orientation and state cognitive anxiety (Hall et al., 1998). It is possible that our ego-involved participants perceived that they had an equal chance of winning and losing, so they may have experienced anxiety before the agility task because they may have doubted whether they would achieve their goal of outperforming their opponent (Lazarus, 2000). Conversely, taskinvolved participants were likely to have focused on their own performance and may have thought they could improve because they had performed the drill a relatively small number of times; therefore, they may not have experienced high anxiety. An unexpected result was that there was no difference in postcompetition happiness between groups. Although no studies have examined the effect of achievement goals on happiness after competition, our results are consistent with recent research showing that enjoyment (which is similar to happiness, see Jones et al., 2005) experienced during a golf-putting task was not different between mastery and performance-approach groups (Kavussanu et al., 2009) and that positive affect during a coordination task did not differ between task and ego groups (Standage et al., 2005). In our experiment, all groups felt moderately happy in practice and competition blocks, which is consistent with research showing that individuals experienced moderate enjoyment when learning a golf putting skill (Kavussanu et al., 2009) and participating in a competitive one-on-one basketball shooting task (Tauer & Harackiewicz,

2004); however, it is unclear why achievement goals had no effect on happiness. Achievement Goals and Performance Our second study purpose was to examine the effect of achievement goals on perceived and actual performance. Results showed that the task group perceived their postcompetition performance to be superior to the control group. The nding is consistent with two previous studies (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011, 2012), which have shown that task involvement positively predicted perceived performance in competition. This nding may have been due to the focus on improving performance, inherent in task involvement (Nicholls, 1989), as well as the improvement of actual performance from practice to competition blocks. The current study extends the literature (Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011, 2012), as it was the rst experiment to investigate, and show an effect of, task involvement on perceived performance. The ego group also reported higher postcompetition perceived performance than the control group. Ego-involved individuals may have believed that they took less time to complete the drill than their opponent. Indeed, research on passage of time judgments suggests that time passes more quickly when individuals are involved in an activity than when they are waiting (Wearden, 2008). Therefore, because of the passage of time judgment and the emphasis on performing well relative to their opponent from the situation and achievement goal manipulation, individuals in the ego group may have thought that they outperformed their opponent, so they had higher perceived performance. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no group differences in actual performance. This result is similar to experimental studies showing no difference in performance between task and ego groups on basketball shooting (Giannini et al., 1988), golf putting (Kavussanu et al., 2009), dart throwing (Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, & Smith, 2009), or basketball dribbling (Elliot, Cury, Fryer, & Huguet, 2006) tasks. A meta-analysis (Utman, 1997) showed that learning (task) and performance (ego) groups displayed similar performance in simple, but not complex, tasks; thus, it is possible that the null result in our experiment was observed because

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

13

the task was simple. This result was unexpected because we did not consider the drill to be simple, given that participants had to remember and execute the foot sequence while exerting maximum effort during the task. Limitations and Future Research Directions This study has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the ndings. First, all participants were informed that they were taking part in a competition, which may have increased ego involvement in all groups; this was unavoidable because we were interested in the effects of goal involvement on emotions and performance in a competitive agility task. Previous research (e.g., Dewar & Kavussanu, 2011; van de Pol & Kavussanu, 2011) has shown that task involvement and orientation is higher than ego involvement and orientation respectively in competition; thus, it is unlikely that ego involvement would have dominated in the task and control groups. Second, we used a handicap system in the ego group to create a challenging task. This may have prevented participants with low perceived ability from experiencing intense negative emotions and low performance. In the future, researchers could examine the degree to which ego involvement affects emotions and performance when a handicap system is not used. Third, our participants were undergraduate students. Using samples from western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies, as was the case in this study, has been criticized because participants from these populations are not representative of the human population as a whole (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Our results can only be generalized to similar populations. In future, it would be advantageous to examine the effects of achievement goals on emotions in athletes from a variety of educational and cultural backgrounds. Fourth, some participants did not adhere to the manipulation, possibly because they did not pay close attention to it or engage with it while it was administered, and were excluded from the main analyses, which is in line with previous research (e.g., Ehrlenspiel et al., 2010; Stanger et al., 2012); however, this is a study limitation. Finally, although our experimental task was high in internal validity, its ecological validity

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

was low, as experimental conditions cannot fully replicate the emotional and social environment of real-world sport competition. This trade-off between internal and external validity is unavoidable in experimental research. Nevertheless, although we can attribute our ndings to our manipulation, their generalizability to real-world sport competition is limited. Future research should investigate whether goal involvement inuences emotions in sport using a quasi-experimental design. Researchers could also examine whether achievement goals inuence whether anxiety is perceived as facilitative or debilitative (see Jones, Hanton, & Swain, 1994).

References

Allen, M. S., Jones, M. V., & Shefeld, D. (2010). The inuence of positive reection on attributions, emotions, and self-efcacy. The Sport Psychologist, 24, 211226. Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 261271. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84 .3.261 Balaguer, I., Duda, J. L., & Crespo, M. (1999). Motivational climate and goal orientation as predictors of perceptions of improvement, satisfaction and coach ratings among tennis players. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 9, 381388. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999 .tb00260.x Biddle, S. J. H., Wang, C. K. J., Kavussanu, M., & Spray, C. M. (2003). Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical activity: A systematic review of research. European Journal of Sport Science, 3, 120. doi:10.1080/ 17461390300073504 Cervell, E., Rosa, F. J. S., Calvo, T. G., Jimenez, R., & Iglesias, D. (2007). Young tennis players competitive task involvement and performance: The role of goal orientations, contextual motivational climate, and coach-initiated motivational climate. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 19, 304 321. doi:10.1080/10413200701329134 Cooke, A., Kavussanu, M., McIntyre, D., & Ring, C. (2011). Effects of competition on endurance performance and the underlying psychological and physiological mechanisms. Biological Psychology, 86, 370 378. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.01 .009 Davies, P. (2011). Ladder agility drills. Retrieved from http://www.sport-tness-advisor.com/ladderagility-drills.html

14

DEWAR, KAVUSSANU, AND RING

Dewar, A. J., & Kavussanu, M. (2011). Achievement goals and emotions in golf: The mediating and moderating role of perceived performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 525532. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.05.005 Dewar, A. J., & Kavussanu, M. (2012). Achievement goals and emotions in team sport athletes. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 1, 254 267. doi:10.1037/a0028692 Downey, R. G., & King, C. V. (1998). Missing data in Likert ratings: A comparison of replacement methods. The Journal of General Psychology, 125, 175191. doi:10.1080/00221309809595542 Ehrlenspiel, F., Wei, K., & Sternad, D. (2010). Openloop, closed-loop and compensatory control: Performance improvement under pressure in a rhythmic task. Experimental Brain Research, 201, 729 741. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-2087-8 Elliot, A. J., Cury, F., Fryer, J. W., & Huguet, P. (2006). Achievement goals, self-handicapping, and performance attainment: A mediational analysis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 28, 344 361. Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 461 475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.461 Giannini, J. M., Weinberg, R. S., & Jackson, A. J. (1988). The effects of mastery, competitive, and cooperative goals on the performance of simple and complex basketball skills. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 10, 408 417. Hall, H. K., & Kerr, A. W. (1997). Motivational antecedents of precompetitive anxiety in youth sport. The Sport Psychologist, 11, 24 42. Hall, H. K., Kerr, A. W., & Matthews, J. (1998). Precompetitive anxiety in sport: The contribution of achievement goals and perfectionism. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 20, 194 217. Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61 83. doi:10.1017/ S0140525X0999152X Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Swain, A. (1994). Intensity and interpretation of anxiety symptoms in elite and non-elite sports performers. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 657 663. doi:10.1016/ 0191-8869(94)90138-4 Jones, M. V., Lane, A. M., Bray, S. R., Uphill, M., & Catlin, J. (2005). Development and validation of the Sport Emotion Questionnaire. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 27, 407 431. Jourden, F. J., Bandura, A., & Baneld, J. T. (1991). The impact of conceptions of ability on selfregulatory factors and motor skill acquisition. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13, 213 226.

Julious, S. A. (2004). Using condence intervals around individual means to assess statistical signicance between two means. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 3, 217222. doi:10.1002/pst.126 Kavussanu, M., Morris, R. L., & Ring, C. (2009). The effects of achievement goals on performance, enjoyment, and practice of a novel motor task. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27, 12811292. doi: 10.1080/02640410903229287 Kavussanu, M., & Roberts, G. C. (2001). Moral functioning in sport: An achievement goal perspective. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 23, 3754. Kelley, K., & Preacher, K. J. (2012). On effect size. Psychological Methods, 17, 137152. doi:10.1037/ a0028086 Lazarus, R. S. (2000). How emotions inuence performance in competitive sports. The Sport Psychologist, 14, 229 252. Nadler, J., & McDonnell, M. H. (2012). Moral character, motive, and the psychology of blame. Cornell Law Review, 97. Northwestern Public Law Research Paper No. 11 43. Retrieved from SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract1814309 Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328 346. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328 Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ntoumanis, N., & Biddle, S. J. H. (1999). Affect and achievement goals in physical activity: A metaanalysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 9, 315332. doi:10.1111/j.16000838.1999.tb00253.x Ntoumanis, N., Thogersen-Ntoumani, C., & Smith, A. L. (2009). Achievement goals, self-handicapping, and performance: A 2 2 achievement goal perspective. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27, 1471 1482. doi:10.1080/02640410903150459 Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satiscing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 867 872. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009 Papaioannou, A., & Kouli, O. (1999). The effect of task structure, perceived motivational climate and goal orientations on students task involvement and anxiety. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 11, 5171. doi:10.1080/10413209908402950 Sage, L., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). The effects of goal involvement on moral behavior in an experimentally manipulated competitive setting. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 29, 190 207. Sarrazin, P., Roberts, G., Cury, F., Biddle, S., & Famose, J.-P. (2002). Exerted effort and performance in climbing among boys: The inuence of

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ACHIEVEMENT GOALS, EMOTIONS, AND PERFORMANCE

15

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

achievement goals, perceived ability, and task difculty. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 73, 425 436. Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.2 .147 Standage, M., Duda, J. L., & Pensgaard, A. M. (2005). The effect of competitive outcome and task-involving, ego-involving, and cooperative structures on the psychological well-being of individuals engaged in a co-ordination task: A selfdetermination approach. Motivation and Emotion, 29, 41 68. doi:10.1007/s11031-005-4415-z Stanger, N., Kavussanu, M., & Ring, C. (2012). Put yourself in their boots: Effects of empathy on emotion and aggression. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 34, 208 222. Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2005). With sadness comes accuracy; with happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychological Science, 16, 785791. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280 .2005.01615.x Tauer, J. M., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2004). The effects of cooperation and competition on intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 849 861. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.6.849 Utman, C. H. (1997). Performance effects of motivational state: A meta-analysis. Personality and

Social Psychology Review, 1, 170 182. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0102_4 van de Pol, P. K. C., & Kavussanu, M. (2011). Achievement goals and motivational responses in tennis: Does the context matter? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 176 183. doi:10.1016/j .psychsport.2010.09.005 Van-Yperen, N. W., & Duda, J. L. (1999). Goal orientations, beliefs about success, and performance improvement among young elite Dutch soccer players. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 9, 358 364. doi:10.1111/j.16000838.1999.tb00257.x Vealey, R. S., & Campbell, J. L. (1988). Achievement goals of adolescent gure skaters: Impact on self-condence, anxiety, and performance. Journal of Adolescent Research, 3, 227243. doi:10.1177/ 074355488832009 Wearden, J. H. (2008). The perception of time: Basic research and some potential links to the study of language. Language Learning, 58 s1, 149 171. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00468.x Williams, L. A., & DeSteno, D. (2008). Pride and perseverance: The motivational role of pride. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 10071017. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1007 Received June 2, 2012 Revision received February 19, 2013 Accepted February 19, 2013

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Your Free Buyer Persona TemplateDocument8 pagesYour Free Buyer Persona Templateel_nakdjoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lista Verbelor Regulate - EnglezaDocument5 pagesLista Verbelor Regulate - Englezaflopalan100% (1)

- Theater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFDocument7 pagesTheater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFJim QuentinPas encore d'évaluation

- AASW Code of Ethics-2004Document36 pagesAASW Code of Ethics-2004Steven TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diode ExercisesDocument5 pagesDiode ExercisesbruhPas encore d'évaluation

- GN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Document87 pagesGN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Miriam B BenniePas encore d'évaluation

- On Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksDocument2 pagesOn Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksTuvshinzaya GantulgaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lorraln - Corson, Solutions Manual For Electromagnetism - Principles and Applications PDFDocument93 pagesLorraln - Corson, Solutions Manual For Electromagnetism - Principles and Applications PDFc. sorasPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil and BrahminsDocument95 pagesTamil and BrahminsRavi Vararo100% (1)

- Romanian Oil IndustryDocument7 pagesRomanian Oil IndustryEnot SoulavierePas encore d'évaluation

- Peri Operative Nursing ManagementDocument19 pagesPeri Operative Nursing ManagementSabina KontehPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting 110: Acc110Document19 pagesAccounting 110: Acc110ahoffm05100% (1)

- 1stQ Week5Document3 pages1stQ Week5Jesse QuingaPas encore d'évaluation

- Edc Quiz 2Document2 pagesEdc Quiz 2Tilottama DeorePas encore d'évaluation

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Document1 pageUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Re CrystallizationDocument25 pagesRe CrystallizationMarol CerdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal Properties of Matter: Centre For Sceince StudyDocument37 pagesThermal Properties of Matter: Centre For Sceince StudySalam FaithPas encore d'évaluation

- The Systems' Institute of Hindu ASTROLOGY, GURGAON (INDIA) (Registered)Document8 pagesThe Systems' Institute of Hindu ASTROLOGY, GURGAON (INDIA) (Registered)SiddharthSharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Document99 pages1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Munir HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature, and The Human Spirit: A Collection of QuotationsDocument2 pagesNature, and The Human Spirit: A Collection of QuotationsAxl AlfonsoPas encore d'évaluation

- BedDocument17 pagesBedprasadum2321Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To ICT EthicsDocument8 pagesIntroduction To ICT EthicsJohn Niño FilipinoPas encore d'évaluation

- 576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Document15 pages576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Sana MuzaffarPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese AstronomyDocument13 pagesChinese Astronomyss13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 6Document15 pagesMathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 6Ray Phillip G. Jorduela0% (1)

- VtDA - The Ashen Cults (Vampire Dark Ages) PDFDocument94 pagesVtDA - The Ashen Cults (Vampire Dark Ages) PDFRafãoAraujo100% (1)

- Marketing Mix of Van HeusenDocument38 pagesMarketing Mix of Van HeusenShail PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- The 5 RS:: A New Teaching Approach To Encourage Slowmations (Student-Generated Animations) of Science ConceptsDocument7 pagesThe 5 RS:: A New Teaching Approach To Encourage Slowmations (Student-Generated Animations) of Science Conceptsnmsharif66Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophy of Education SyllabusDocument5 pagesPhilosophy of Education SyllabusGa MusaPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Numbers: SeriesDocument13 pagesTypes of Numbers: SeriesAnonymous NhQAPh5toPas encore d'évaluation