Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Consti Law 1

Transféré par

Eloisa Katrina MadambaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Consti Law 1

Transféré par

Eloisa Katrina MadambaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION vs.

EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Political Law Ex Officio Officials EO 284 On 25 July 1987, Cory issued EO 284 which allows members of the Cabinet, their undersecretaries and assistant secretaries to hold other government offices or positions in addition to their primary positions subject to limitations set therein. The CLU excepted this EO averring that such law is unconstitutional. The constitutionality of EO 284 is being challenged by CLU on the principal submission that it adds exceptions to Sec 13, Art 7 other than those provided in the Constitution; CLU avers that by virtue of the phrase unless otherwise provided in this Constitution, the only exceptions against holding any other office or employment in Government are those provided in the Constitution, namely: (i) The Vice-President may be appointed as a Member of the Cabinet under Sec 3, par. (2), Article 7; and (ii) the Secretary of Justice is an ex-officio member of the Judicial and Bar Council by virtue of Sec 8 (1), Article 8. ISSUE: Whether or not EO 284 is constitutional. HELD: Sec 13, Art 7 provides: Sec. 13. The President, Vice-President, the Members of the Cabinet, and their deputies or assistants shall not, unless otherwise provided in this Constitution, hold any other office or employment during their tenure. They shall not, during said tenure, directly or indirectly practice any other profession, participate in any business, or be financially interested in any contract with, or in any franchise, or special privilege granted by the Government or any subdivision, agency, or instrumentality thereof, including government-owned or controlled corporations or their subsidiaries. They shall strictly avoid conflict of interest in the conduct of their office. It is clear that the 1987 Constitution seeks to prohibit the President, Vice-President, members of the Cabinet, their deputies or assistants from holding during their tenure multiple offices or employment in the government, except in those cases specified in the Constitution itself and as above clarified with respect to posts held without additional compensation in an ex-officio capacity as provided by law and as required by the primary functions of their office, the citation of Cabinet members (then called Ministers) as examples during the debate and deliberation on the general rule laid down for all appointive officials should be considered as mere personal opinions which cannot override the constitutions manifest intent and the peoples understanding thereof. In the light of the construction given to Sec 13, Art 7 in relation to Sec 7, par. (2), Art IX-B of the 1987 Constitution, EO 284 is unconstitutional. Ostensibly restricting the number of positions that Cabinet members, undersecretaries or assistant secretaries may hold in addition to their primary position to not more than 2 positions in the government and government corporations, EO 284 actually allows them to hold multiple offices or employment in direct contravention of the express mandate of Sec 13, Art 7 of the 1987 Constitution prohibiting them from doing so, unless otherwise provided in the 1987 Constitution itself.

GONZALES vs. COMELEC Constitutional Law Political Question vs Justiciable Question Facts: ? One of the issues raised in this case was the validity of the submission of certain proposed constitutional amendments at a plebiscite scheduled on the same day as the regular elections. Petitioners argued that this was unlawful as there would be no proper submission of the proposal to the people who would be more interested in the issues involved in the election. It was contended that such issue cannot be properly raised before the courts because it is a political one. ISSUE: Whether or not the issue involves a political question. HELD: Pursuant to Art 15 of the 35 Constitution, SC held that there is nothing in this provision to indicate that the election therein referred to is a special, not a general election. The circumstance that the previous amendment to the Constitution had been submitted to the people for ratification in special elections merely shows that Congress deemed it best to do so under the circumstances then obtaining. It does not negate its authority to submit proposed amendments for ratification in general elections. The SC also noted that if what is placed in question or if the crux of the problem is the validity of an act then the same would be or the issue would be considered as a justiciable question NOT a political one.

IMBONG vs COMELEC September 11, 1970 RA 6132: delegates in ConCon (Contitutional Law 1) Petitioner: Imbong Respondents: Ferrer (Comelec Chair), Patajo, Miraflor (Comelec Members) Petitioner: Gonzales Respondent : Comelec Ponente: Makasiar RELATED LAWS: Resolution No 2 (1967) Calls for Constitutional Convention to be composed of 2 delegates from each representative district who shall be elected in November, 1970. RA 4919 implementation of Resolution No 2 Resolution 4 (1969) amended Resolution 2: ConCon shall be composed of 320 delegates approportioned among existing representative districts according to the population. Provided that each district shall be entitled to 2 deledates. RA 6132 Concon Act 1970, repealed RA 4919, implemented Res No. 2 & 4. Sec 4: considers all public officers/employees as resigned when they file their candicacy Sec 2: apportionment of delegates Sec 5: Disqualifies any elected delegate from running for any public office in the election or from assuming any appointive office/position until the final adournment of the ConCon. Par 1 Sec 8: ban against all political parties/organized groups from giving support/representing a delegate to the convention. FACTS: This is a petition for declaratory judgment. These are 2 separate but related petitions of running candidates for delegates to the Constitutional Convention assailing the validity of RA 6132. Gonzales: Sec, 2, 4, 5 and Par 1 Sec 8, and validity of entire law Imbong: Par 1 Sec 8 ISSUE: Whether the Congress has a right to call for ConCon and whether the parameters set by such a call is constitutional. HOLDING: The Congress has the authority to call for a Constitutional Convention as a Constituent Assembly. Furthermore, specific provisions assailed by the petitioners are deemed as constitutional.

y Sec 4 RA 6132: it is simply an application of Sec 2 Art 12 of Constitution y Constitutionality of enactment of RA 6132: Congress acting as Constituent Assembly, has full authority to propose amendments, or call for convention for the purpose by votes and these votes were attained by Res 2 and 4 Y

Sec 2 RA 6132: it is a mere implementation of Res 4 and is enough that the basis employed for such apportions is reasonable. Macias case relied by Gonsales is not reasonable for that case granted more representatives to provinces with less population and vice versa. In this case, Batanes is equal to the number of delegates I other provinces with more population. y Sec 5: State has right to create office and parameters to qualify/disqualify members thereof. Furthermore, this disqualification is only temporary. This is a safety mechanism to prevent political figures from controlling elections and to allow them to devote more time to the Concon. y Par 1 Sec 8: this is to avoid debasement of electoral process and also to assure candidates equal opportunity since candidates must now depend on their individual merits, and not the support of political parties. This provision does not create discrimination towards any particular party/group, it applies to all organizations

BAUTISTA vs. SALONGA Facts: ? On 27 Aug 1987, Cory designated Bautista as the Acting Chairwoman of CHR. In December of the same year, Cory made the designation of Bautista permanent. The CoA, ignoring the decision in the Mison case, averred that Bautista cannot take her seat w/o their confirmation. Cory, through the Exec Sec, filed with the CoA communications about Bautistas appointment on 14 Jan 1989. Bautista refused to be placed under the CoAs review hence she filed a petition before the SC. On the other hand, Mallillin invoked EO 163-A stating that since CoA refused Bautistas appointment, Bautista should be removed. EO 163-A provides that the tenure of the Chairman and the Commissioners of the CHR should be at the pleasure of the President. ISSUE: Whether or not Bautistas appointment is subject to CoAs confirmation. HELD: Since the position of Chairman of the CHR is not among the positions mentioned in the first sentence of Sec. 16, Art. 7 of the 1987 Constitution, appointments to which are to be made with the confirmation of the CoA it follows that the appointment by the President of the Chairman of the CHR is to be made without the review or participation of the CoA. To be more precise, the appointment of the Chairman and Members of the CHR is not specifically provided for in the Constitution itself, unlike the Chairmen and Members of the CSC, the CoE and the COA, whose appointments are expressly vested by the Constitution in the President with the consent of the CoA. The President appoints the Chairman and Members of the CHR pursuant to the second sentence in Sec 16, Art. 7, that is, without the confirmation of the CoA because they are among the officers of government whom he (the President) may be authorized by law to appoint. And Sec 2(c), EO 163 authorizes the President to appoint the Chairman and Members of the CHR. Because of the fact that the president submitted to the CoA on 14 Jan 1989 the appointment of Bautista, the CoA argued that the president though she has the sole prerogative to make CHR appointments may from time to time ask confirmation with the CoA. This is untenable according to the SC. The Constitution has blocked off certain appointments for the President to make with the participation of the Commission on Appointments, so also has the Constitution mandated that the President can confer no power of participation in the Commission on Appointments over other appointments exclusively reserved for her by the Constitution. The exercise of political options that finds no support in the Constitution cannot be sustained. Further, EVEN IF THE PRESIDENT MAY VOLUNTARILY SUBMIT TO THE COMMISSION ON APPOINTMENTS AN APPOINTMENT THAT UNDER THE CONSTITUTION SOLELY BELONGS TO HER, STILL, THERE WAS NO VACANCY TO WHICH AN APPOINTMENT COULD BE MADE ON 14 JANUARY 1989. There can be no ad interim appointments in the CHR for the appointment thereto is not subject to CoAs confirmation. Appointments to the CHr is always permanent in nature. The provisions of EO 163-A is unconstitutional and cannot be invoked by Mallillin. The Chairman and the Commissioners of the CHR cannot be removed at the pleasure of the president for it is constitutionally guaranteed that they must have a term of office.

OCCENA vs. COMELEC [GR 56350, 2 April 1981]; also Gonzales vs. National Treasurer [GR 56404] En Banc, Fernando (CJ): 8 concur, 1 dissents in separate opinion, 1 on official leave Facts: The challenge in these two prohibition proceedings against the validity of three Batasang Pambansa Resolutions proposing constitutional amendments, goes further than merely assailing their alleged constitutional infirmity. Samuel Occena and Ramon A. Gonzales, both members of the Philippine Bar and former delegates to the 1971 Constitutional Convention that framed the present Constitution, are suing as taxpayers. The rather unorthodox aspect of these petitions is the assertion that the 1973 Constitution is not the fundamental law, the Javellana ruling to the contrary notwithstanding. Issue: Whether the 1973 Constitution was valid, and in force and effect when the Batasang Pambansa resolutions and the present petitions were promulgated and filed, respectively. Held: It is much too late in the day to deny the force and applicability of the 1973 Constitution. In the dispositive portion of Javellana v. The Executive Secretary, dismissing petitions for prohibition and mandamus to declare invalid its ratification, this Court stated that it did so by a vote of six to four. It then concluded: "This being the vote of the majority, there is no further judicial obstacle to the new Constitution being considered in force and effect." Such a statement served a useful purpose. It could even be said that there was a need for it. It served to clear the atmosphere. It made manifest that as of 17 January 1973, the present Constitution came into force and effect. With such a pronouncement by the Supreme Court and with the recognition of the cardinal postulate that what the Supreme Court says is not only entitled to respect but must also be obeyed, a factor for instability was removed. Thereafter, as a matter of law, all doubts were resolved. The 1973 Constitution is the fundamental law. It is as simple as that. What cannot be too strongly stressed is that the function of judicial review has both a positive and a negative aspect. As was so convincingly demonstrated by Professors Black and Murphy, the Supreme Court can check as well as legitimate. In declaring what the law is, it may not only nullify the acts of coordinate branches but may also sustain their validity. In the latter case, there is an affirmation that what was done cannot be stigmatized as constitutionally deficient. The mere dismissal of a suit of this character suffices. That is the meaning of the concluding statement in Javellana. Since then, this Court has invariably applied the present Constitution. The latest case in point is People v. Sola, promulgated barely two weeks ago. During the first year alone of the effectivity of the present Constitution, at least ten cases may be cited.

TOLENTINO vs. COMELEC FACTS: The case is a petition for prohibition to restrain respondent Commission on Elections "from undertaking to hold a plebiscite on November 8, 1971," at which the proposed constitutional amendment "reducing the voting age" in Section 1 of Article V of the Constitution of the Philippines to eighteen years "shall be, submitted" for ratification by the people pursuant to Organic Resolution No. 1 of the Constitutional Convention of 1971, and the subsequent implementing resolutions, by declaring said resolutions to be without the force and effect of law for being violative of the Constitution of the Philippines. The Constitutional Convention of 1971 came into being by virtue of two resolutions of the Congress of the Philippines approved in its capacity as a constituent assembly convened for the purpose of calling a convention to propose amendments to the Constitution namely, Resolutions 2 and 4 of the joint sessions of Congress held on March 16, 1967 and June 17, 1969 respectively. The delegates to the said Convention were all elected under and by virtue of said resolutions and the implementing legislation thereof, Republic Act 6132.

ISSUE: Is it within the powers of the Constitutional Convention of 1971 to order the holding of a plebiscite for the ratification of the proposed amendment/s.

HELD: The Court holds that all amendments to be proposed must be submitted to the people in a single "election" or plebiscite. We hold that the plebiscite being called for the purpose of submitting the same for ratification of the people on November 8, 1971 is not authorized by Section 1 of Article XV of the Constitution, hence all acts of the Convention and the respondent Comelec in that direction are null and void. lt says distinctly that either Congress sitting as a constituent assembly or a convention called for the purpose "may propose amendments to this Constitution,". The same provision also as definitely provides that "such amendments shall be valid as part of this Constitution when approved by a majority of the votes cast at an election at which the amendments are submitted to the people for their ratification," thus leaving no room for doubt as to how many "elections" or plebiscites may be held to ratify any amendment or amendments proposed by the same constituent assembly of Congress or convention, and the provision unequivocably says "an election" which means only one. The petition herein is granted. Organic Resolution No. 1 of the Constitutional Convention of 1971 and the implementing acts and resolutions of the Convention, insofar as they provide for the holding of a plebiscite on November 8, 1971, as well as the resolution of the respondent Comelec complying therewith (RR Resolution No. 695) are hereby declared null and void. The respondents Comelec, Disbursing Officer, Chief Accountant and Auditor of the Constitutional Convention are hereby enjoined from taking any action in compliance with the said organic resolution. In view of the peculiar circumstances of this case, the Court declares this decision immediately executory. No costs .

JAVELLANA vs. EXECUTIVE SECRETARY Facts: ? In 1973, Marcos ordered the immediate implementation of the new 1973 Constitution. Javellana, a Filipino and a registered voter sought to enjoin the Exec Sec and other cabinet secretaries from implementing the said constitution. Javellana averred that the said constitution is void because the same was initiated by the president. He argued that the president is w/o power to proclaim the ratification by the Filipino people of the proposed constitution. Further, the election held to ratify such constitution is not a free election there being intimidation and fraud. ISSUE: Whether or not the SC must give due course to the petition. HELD: The SC ruled that they cannot rule upon the case at bar. Majority of the SC justices expressed the view that they were concluded by the ascertainment made by the president of the Philippines, in the exercise of his political prerogatives. Further, there being no competent evidence to show such fraud and intimidation during the election, it is to be assumed that the people had acquiesced in or accepted the 1973 Constitution. The question of the validity of the 1973 Constitution is a political question which was left to the people in their sovereign capacity to answer. Their ratification of the same had shown such acquiescence.

DE LEON vs. ESGUERRA Facts: Alfredo de Leon won as barangay captain and other petitioners won as councilmen of barangay dolores, taytay, rizal. On february 9, 1987, de leon received memo antedated december 1, 1986 signed by OIC Gov. Benhamin Esguerra, february 8, 1987, designating Florentino Magno, as new captain by authority of minister of local government and similar memo signed february 8, 1987, designated new councilmen. Issue: Whether or not designation of successors is valid. Held: No, memoranda has no legal effect. 1. Effectivity of memoranda should be based on the date when it was signed. So, February 8, 1987 and not December 1, 1986. 2. February 8, 1987, is within the prescribed period. But provisional constitution was no longer in efffect then because 1987 constitution has been ratified and its transitory provision, Article XVIII, sec. 27 states that all previous constitution were suspended. 3. Constitution was ratified on February 2, 1987. Thus, it was the constitution in effect. Petitioners now acquired security of tenure until fixed term of office for barangay officials has been fixed. Barangay election act is not inconsistent with constitution.

SANIDAD vs. COMELEC Facts: On 2 September 1976, President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued P D 9 9 1 c a l l i n g f o r a n a t i o n a l referendum on 16 October 1976 for the Citizens Assemblies ("barangays") to resolve the issues of martial law, the interim assembly, its replacement, the powers of such replacement, the period of its existence, the length of the period for the exercise by the President of his present powers. On 22 September 1976, the President issued another PD 1031, amending the previous Presidential Decree 991, by declaring the provisions of Presiden tial Decree 229 providing for the manner of voting and canvass of votes in "barangays" (Citizens Assemblies) applicable to the national referendum-plebiscite of 16 October 1976. The President also issued PD 1033, stating the questions to be submitted to the people in the referendum - plebiscite on 16 October 1976. The Decree recites in its "whereas" clauses that the people's continued opposition to the convening of the interim Natio nal Assembly evinces their desire to have such body abolished and replaced thru a constitutional amendment, providing for a new interim legislative body, which will be submitted directly to the people in the referendum-plebiscite of October 16. The Commission on Elections was vested with the exclusive supervision and control of the October 1976 National Referendum-Plebiscite. P a b l o C . S a n i d a d a n d P a b l i t o V. S a n i d a d , f a t h e r a n d s o n , c o m m e n c e d f o r P r o h i b i t i o n w i t h Preliminary Injunction seeking to enjoin the COMELEC from holding and conducting the Referendum Plebiscite on October 16; to declare without force and effect PD 991, 1033 and 1031. They contend that under the 1935 and 1973 Constitutions there is no grant to the incumbent President to exercise the constituent power to propose amendments to the new Constitution. On 30 September 1976, another action for Prohibition with Preliminary Injunction, was instituted by Vicente M. Guzman, a delegate to the 1971 Constitutional Convention, asserting that the power to propose amendments to, or revision of the Constitution during the transition period is expressly conferred o n t h e i n t e r i m National Assembly under action 16, Article XVII of t h e Constitution. Another petition for Prohibition with Preliminary Injunction was filed by Raul M. Gonzales, his son, and Alfredo Salapantan, to restrain the implementation of Presidential Decrees. Issue: W/N the President may call upon a referendum for the amendment of the Constitution. Held: Section 1 of Article XVI of the 1973 Constitution on Amendments ordains that "(1) Any amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution may be proposed by the National Assembly upon a vote of three-fourths of all its Members, or by a constitutional co nvention. (2) The National Assembly may, by a vote of two - thirds of all its Members, call a constitutional convention or, by a majority vote of all its Members, submit the question of calling such a convention to the electorate in an election." Section 2 thereof provides that "Any amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution shall be valid when ratified by a majority of the

votes c a s t i n a p l e b i s c i t e w h i c h s h a l l b e h e l d n o t l a t e r t h a n t h r e e m o n t h s a a f t e r t h e a p p r o v a l o f s u c h amendment or revision." In the present period of transition, the interim National Assembly instituted in the Transitory Provisions is conferred with that amending power. Section 15 of the Transitory Provisi ons reads "The interim National Assembly, upon special call by the interim Prime Minister, may, by a majority vote of all its Members, propose amendments to this Constitution. Such amendments shall take effect when ratified in accordance with Article 16 hereof." There are, therefore, two periods contem plated in the constitutional life of the natio n: period of normalcy and period of transition. In times of normalcy, the amending process may be initiated by the proposals of the (1) regular National Assembly upon a vote of three-fourths of all its members; or (2) by aConstitutional Convention called by a vote of two - thirds of all the Members of the National Assembly. However the calling of a Constitutional Co nvention m ay be submitted to the electorate in an e lection v o t e d u p o n b y a m a j o r i t y v o t e o f a l l t h e m e m b e r s o f t h e N a t i o n a l A s s e m b l y. I n t i m e s o f t r a n s i t i o n amendments may be proposed by a majority vote of all the Members of the interim National Assembly upon special call by the interim Prime Minister. The Court in Aquino v. COMELEC, had already settled that the incumbent President is vested with that prerogative of discretion as to when he shall initially convene the interim National Assembly. The Constitutional Convention intended to leave to the President the determination of the time when he shall initially co nvene the interim National Assembly, co nsistent with the prevailing conditions of peace and order in the country. When the Delegates to the Constitutional Convention voted on the Transitory Provisions, they were aware of the fact that under the same, the incumbent President was given the discretion as to when he could convene the interim National Assembly. The President's decision to defer the co nvening of the interim National Assembly soon found support from the people themselves. In the plebiscite of January 10 - 15, 1973, at which the ratificatio n of the 1973 Constitution was submitted, the people voted against the convening of the interim National Assembly. In the referendum of 2 4 J u l y 1973, the Citizens Assemblies ("bagangays") reiterated their s o v e r e i g n w i l l t o w i t h h o l d t h e convening of the interim National Assembly. Again, in the referendum of 27 February 1975, the proposed question of whether the interim National Assembly shall be initially co nvened was eliminated, because some of the members of Congress and delegates of the Constitutional Convention, who were deemed a u t o m a t i c a l l y m e m b e r s o f t h e i n t e r i m N a t i o n a l A s s e m b l y , w e r e a g a i n s t i t s i n c l u s i o n s i n c e i n t h a t referendum of January, 1973 the people had already resolved against it. In sensu striciore, when the legislative arm of the state undertakes the proposals of amendment to a Constitution, that body is not in the usual functio n of lawmaking. It is not legislating when engaged in the amending process. Rather, it is exercising a peculiar power besto wed upon it by the fundamental charter itself. In the Philippines, that power is provided for in Article XVI of the 1973 Constitution (for the regular National Assembly) or in Section 15 of the Transitory Provisions (for

the interim National Assembly). While ordinarily it is the business of the legislating body to legislate for the nation by virtue of constitutional conferment, amending of the Constitution is not legislative in character. In political science a distinction is made between constitutional content of an organic character and that of a legislative character. The distinction, however, is one of policy, not of law. Such being the case, approval of the President of any proposed amendment is a misnomer. The prerogative of the President to approve o r d i s a p p r o v e a p p l i e s o n l y t o t h e o r d i n a r y c a s e s o f l e g i s l a t i o n . T h e P r e s i d e n t h a s n o t h i n g t o d o w i t h proposition or adoption of amendments to the Constitution.

DEFENSOR SANTIAGO vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 127325 - March 19, 1997) Facts: Private respondent Atty. Jesus Delfin, president of P e o p l e s I n i t i a t i v e f o r R e f o r m s , Modernization and Action (PIRMA), filed with COMELEC a petition to amend the constitution to lift the term limits of elective officials, through Peoples Initiative. He based this petition on Article XVII, Sec. 2 of the 1987 Constitution, which provides for the right o f the people to exercise the power to directly propose amendments to the Constitutio n. Subsequently the COMELEC issued an o rder directing the publication of the petitio n and of the notice of hearing and thereafter set the case for hearing. At the hearing, Senator Roco, the IBP, Demokrasya-Ipagtanggol ang Konstitusyon, Public Interest L aw Center, and Laban ng Demokratikong Pilipino appeared as interveno rs - oppositors. Senator Roco filed a motion to dismiss the Delfin petition on the ground that one which is cognizable by the COMELEC. The petitioners herein Senator Santiago, Alexander Padilla, and Isabel Ongpin filed this civil action for pro hibition under Rule 6 5 of the Rules of Court against COMELEC and the Delfin petition rising the several arguments, such as the following: (1) The constitutional provision on p e o p l e s i n i t i a t i v e t o a m e n d t h e constitution can only be implemented by law to be passed by Congress. No such law has been passed; (2) The peoples initiative is limited to amendments to the Constitution, not to revision thereof. Lifting of the term limits constitutes a revision, therefore it is outside the power of peoples initiative. The Supreme Court granted the Motions for Intervention. Issues: (1) Whether or not Sec. 2, Art. XVII of the 1987 Constitution is a self-executing provision. (2) Whether or not COMELEC Resolution No. 2300 regarding the conduct of initiative o n amendments to the Constitution is valid, considering the absence in the law of specific provisions on the conduct of such initiative. (3) Whether the lifting of term limits of elective officials would constitute a revision or an amendment of the Constitution. Held: S e c . 2 , A r t X V I I o f t h e C o n s t i t u t i o n i s n o t s e l f e x e c u t o r y , t h u s , w i t h o u t i m p l e m e n t i n g legislation the same cannot operate. Although the Constitution has recognized or granted the right, the people cannot exercise it if Congress does not provide for its implementation. The portion of COMELEC Resolution No. 2300 which prescribes rules and regulations on the conduct of initiative on amendments to the Constitution, is void. It has been an established rule that w h a t h a s b e e n d e l e g a t e d , c a n n o t b e d e l e g a t e d ( p o t e s t a s d e l e g a t a n o n d e l e g a r i p o t e s t ) . T h e delegation of the power to the COMELEC being invalid, the latter cannot validly promulgate rules and regulations to implement the exercise of the right to peoples initiative. T h e l i f t i n g o f t h e term limits was held to be that of a revision, as it would affect o t h e r provisions of the Constitution such as the synchronization of elections, the constitutional guarantee of equal access to opportunities for public service, and prohibiting political dynasties. A revisio n cannot be done by initiative. However, considering the Courts decision in the above Issue, the issue of whether or not the petition is a revision or amendment has become academic.

LAMBINO vs. COMELEC G.R. No. 174153, Oct. 25, 2006 (CARPIO, J.) Requirements for Initiative Petition Constitutional Amendment vs. Constitutional Revision Tests to determine whether amendment or revision FACTS: The Lambino Group commenced gathering signatures for an initiative petition to change the 1987 Constitution and then filed a petition with COMELEC to hold a plebiscite for ratification under Sec. 5(b) and (c) and Sec. 7 of RA 6735. The proposed changes under the petition will shift the present Bicameral-Presidential system to a Unicameral-Parliamentary form of government. COMELEC did not give it due course for lack of an enabling law governing initiative petitions to amend the Constitution, pursuant to Santiago v. Comelec ruling ISSUES: Whether or not the proposed changes constitute an amendment or revision Whether or not the initiative petition is sufficient compliance with the constitutional requirement on direct proposal by the people RULING: Initiative petition does not comply with Sec. 2, Art. XVII on direct proposal by people Sec.2, Art. XVII...is the governing provision that allows a peoples initiative to propose amendments to the Constitution. While this provision does not expressly state that the petition must set forth the full text of the proposed amendments, the deliberations of the framers of our Constitution clearly show that: (a) the framers intended to adopt relevant American jurisprudence on peoples initiative; and (b) in particular, the people must first seethe full text of the proposed amendments before they sign, and that the people must sign on a petition containing such full text. The essence of amendments directly proposed by the people through initiative upon a petition is that the entire proposal on its face is a petition by the people. This means two essential elements must be present. 2 elements of initiative 1. First, the people must author and thus sign the entire proposal. No agent or representative can sign on their behalf. 2.Second, as an initiative upon a petition, the proposal must be embodied in a petition. These essential elements are present only if the full text of the proposed amendments is first shown to the people who express their assent by signing such complete proposal in a petition. The full text of the proposed amendments may be either written on the face of the petition, or attached to it. If so attached, the petition must stated the fact of such attachment. This is an assurance that every one of the several millions of signatories to the petition had seen the full text of the proposed amendments before not after signing. Moreover, an initiative signer must be informed at the time of signing of the nature and effect of that which is proposed and failure to do so is deceptive and misleading which renders the initiative void.

In the case of the Lambino Groups petition, theres not a single word, phrase, or sentence of text of the proposed changes in the signature sheet. Neither does the signature sheet state that the text of the proposed changes is attached to it. The signature sheet merely asks a question whether the people approve a shift from the Bicameral-Presidential to the UnicameralParliamentary system of government. The signature sheet does not show to the people the draft of the proposed changes before they are asked to sign the signature sheet. This omission is fatal. An initiative that gathers signatures from the people without first showing to the people the full text of the proposed amendments is most likely a deception, and can operate as a gigantic fraud on the people. Thats why the Constitution requires that an initiative must be directly proposed by the people x x x in a petition - meaning that the people must sign on a petition that contains the full text of the proposed amendments. On so vital an issue as amending the nations fundamental law, the writing of the text of the proposed amendments cannot be hidden from the people under a general or special power of attorney to unnamed, faceless, and unelected individuals. The initiative violates Section 2, Article XVII of the Constitution disallowing revision through initiatives article XVII of the Constitution speaks of three modes of amending the Constitution. The first mode is through Congress upon three-fourths vote of all its Members. The second mode is through a constitutional convention. The third mode is through a peoples initiative. Section 1 of Article XVII, referring to the first and second modes, applies to any amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution. In contrast, Section 2 of Article XVII, referring to the third mode, applies only to amendments to this Constitution. This distinction was intentional as shown by the deliberations of the Constitutional Commission. A peoples initiative to change the Constitution applies only to an amendment of the Constitution and not to its revision. In contrast, Congress or a constitutional convention can propose both amendments and revisions to the Constitution. Does the Lambino Groups initiative constitute a revision of the Constitution? Yes. By any legal test and under any jurisdiction, a shift from a Bicameral-Presidential to a Unicameral-Parliamentary system, involving the abolition of the Office of the President and the abolition of one chamber of Congress, is beyond doubt a revision, not a mere amendment. Amendment vs. Revision Courts have long recognized the distinction between an amendment and a revision of a constitution. Revision broadly implies a change that alters a basic principle in the constitution, like altering the principle of separation of powers or the system of checks-andbalances. There is also revision if the change alters the substantial entirety of the constitution, as when the change affects substantial provisions of the constitution. On the other hand, amendment broadly refers to a change that adds, reduces, or deletes without altering the basic principle involved. Revision generally affects several provisions of the constitution, while amendment generally affects only the specific provision being amended. Where the proposed change applies only to a specific provision of the Constitution without affecting any other section or article, the change may generally be considered an amendment and not a revision. For example, a change reducing the voting age from 18years to 15 years is an amendment and not a revision.

Similarly, a change reducing Filipino ownership of mass media companies from 100% to 60% is an amendment and not a revision. Also, a change requiring a college degree as an additional qualification for election to the Presidency is an amendment and not a revision. The changes in these examples do not entail any modification of sections or articles of the Constitution other than the specific provision being amended. These changes do not also affect the structure of government or the system of checks-and-balances among or within the three branches. However, there can be no fixed rule on whether a change is an amendment or a revision. A change in a single word of one sentence of the Constitution may be a revision and not an amendment. For example, the substitution of the word republican with monarchic or theocratic in Section 1, Article II of the Constitution radically overhauls the entire structure of government and the fundamental ideological basis of the Constitution. Thus, each specific change will have to be examined case-by-case, depending on how it affects other provisions, as well as how it affects the structure of government, the carefully crafted system of checksand-balances, and the underlying ideological basis of the existing Constitution. Since a revision of a constitution affects basic principles, or several provisions of a constitution, a deliberative body with recorded proceedings is best suited to undertake a revision. A revision requires harmonizing not only several provisions, but also the altered principles with those that remain unaltered. Thus, constitutions normally authorize deliberative bodies like constituent assemblies or constitutional conventions to undertake revisions. On the other hand, constitutions allow peoples initiatives, which do not have fixed &identifiable deliberative bodies or recorded proceedings, to undertake only amendments & not revisions. Tests to determine whether amendment or revision In California where the initiative clause allows amendments but not revisions to the constitution just like in our Constitution, courts have developed a two-part test: the quantitative test and the qualitative test. The quantitative test asks whether the proposed change is so extensive in its provisions as to change directly the substantial entirety of the constitution by the deletion or alteration of numerous existing provisions. The court examines only the number of provisions affected and does not consider the degree of the change. The qualitative test inquires into the qualitative effects of the proposed change in the constitution. The main inquiry is whether the change will accomplish such far reaching changes in the nature of our basic governmental plan as to amount to a revision. Whether there is an alteration in the structure of government is a proper subject of inquiry. Thus, a change in the nature of [the] basic governmental plan includes change in its fundamental framework or the fundamental powers of its Branches. A change in the nature of the basic governmental plan also includes changes that jeopardize the traditional form of government & the system of check and balances Under both the quantitative and qualitative tests, the Lambino Groups initiative is a revision &Not merely an amendment. Quantitatively, the Lambino Groups proposed changes overhaul two articles - Article VI on the Legislature and Article VII on the Executive -affecting a total of 105 provisions in the entire Constitution. Qualitatively, the proposed changes alter

substantially the basic plan of government, from presidential to parliamentary, and from a bicameral to a unicameral legislature. A change in the structure of government is a revision A change in the structure of government is a revision of the Constitution, as when the three great co-equal branches of government in the present Constitution are reduced into two. This alters the separation of powers in the Constitution. A shift from the present BicameralPresidential system to a Unicameral-Parliamentary system is a revision of the Constitution. Merging the legislative and executive branches is a radical change in the structure of government. The abolition alone of the Office of the President as the locus of Executive Power alters the separation of powers and thus constitutes a revision of the Constitution. Likewise, the abolition alone of one chamber of Congress alters the system of checks-andbalances within the legislature and constitutes a revision of the Constitution. The Lambino Group theorizes that the difference between amendment and revision is only one of procedure, not of substance. The Lambino Group posits that when a deliberative body drafts and proposes changes to the Constitution, substantive changes are called revisions because members of the deliberative body work full-time on the changes. The same substantive changes, when proposed through an initiative, are called amendments because the changes are made by ordinary people who do not make an occupation, profession, or vocation out of such endeavor. The SC, however, ruled that the express intent of the framers and the plain language of the Constitution contradict the Lambino Groups theory. Where the intent of the framers and the language of the Constitution are clear and plainly stated, courts do not deviate from such categorical intent and language.

MANILA PRINCE HOTEL vs. GSIS 267 SCRA 402 February 1997 En Banc FACTS: Pursuant to the privatization program of the government, GSIS chose to award during bidding in September 1995 the 51% outstanding shares of the respondent Manila Hotel Corp. (MHC) to the Renong Berhad, a Malaysian firm, for the amount of Php 44.00 per share against herein petitioner which is a Filipino corporation who offered Php 41.58 per share. Pending the declaration of Renong Berhad as the winning bidder/strategic partner of MHC, petitioner matched the formers bid prize also with Php 44.00 per share followed by a managers check worth Php 33 million as Bid Security, but the GSIS refused to accept both the bid match and the managers check. One day after the filing of the petition in October 1995, the Court issued a TRO enjoining the respondents from perfecting and consummating the sale to the Renong Berhad. In September 1996, the Supreme Court En Banc accepted the instant case. ISSUE: Whether or not the GSIS violated Section 10, second paragraph, Article 11 of the 1987 Constitution COURT RULING: The Supreme Court directed the GSIS and other respondents to cease and desist from selling the 51% shares of the MHC to the Malaysian firm Renong Berhad, and instead to accept the matching bid of the petitioner Manila Prince Hotel. According to Justice Bellosillo, ponente of the case at bar, Section 10, second paragraph, Article 11 of the 1987 Constitution is a mandatory provision, a positive command which is complete in itself and needs no further guidelines or implementing laws to enforce it. The Court En Banc emphasized that qualified Filipinos shall be preferred over foreigners, as mandated by the provision in question. The Manila Hotel had long been a landmark, therefore, making the 51% of the equity of said hotel to fall within the purview of the constitutional shelter for it emprises the majority and controlling stock. The Court also reiterated how much of national pride will vanish if the nations cultural heritage will fall on the hands of foreigners. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Puno said that the provision in question should be interpreted as pro-Filipino and, at the same time, not anti-alien in itself because it does not prohibit the State from granting rights, privileges and concessions to foreigners in the absence of qualified Filipinos. He also argued that the petitioner is estopped from assailing the winning bid of Renong Berhad because the former knew the rules of the bidding and that the foreigners are qualified, too.

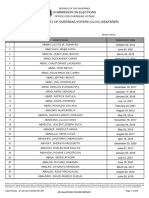

PAMATONG vs. COMELEC

FACTS: Petitioner Pamatong filed his Certificate of Candidacy (COC) for President. Respondent COMELEC declared petitioner and 35 others as nuisance candidates who could not wage a nationwide campaign and/or are not nominated by a political party or are not supported by a registered political party with a national constituency. Pamatong filed a Petition For Writ of Certiorari with the Supreme Court claiming that the COMELEC violated his right to "equal access to opportunities for public service" under Section 26, Article II of the 1987 Constitution, by limiting the number of qualified candidates only to those who can afford to wage a nationwide campaign and/or are nominated by political parties. The COMELEC supposedly erred in disqualifying him since he is the most qualified among all the presidential candidates, i.e., he possesses all the constitutional and legal qualifications for the office of the president, he is capable of waging a national campaign since he has numerous national organizations under his leadership, he also has the capacity to wage an international campaign since he has practiced law in other countries, and he has a platform of government. ISSUE: Is there a constitutional right to run for or hold public office? RULING: No. What is recognized in Section 26, Article II of the Constitution is merely a privilege subject to limitations imposed by law. It neither bestows such a right nor elevates the privilege to the level of an enforceable right. There is nothing in the plain language of the provision which suggests such a thrust or justifies an interpretation of the sort. The "equal access" provision is a subsumed part of Article II of the Constitution, entitled "Declaration of Principles and State Policies." The provisions under the Article are generally considered not self-executing, and there is no plausible reason for according a different treatment to the "equal access" provision. Like the rest of the policies enumerated in Article II, the provision does not contain any judicially enforceable constitutional right but merely specifies a guideline for legislative or executive action. The disregard of the provision does not give rise to any cause of action before the courts. Obviously, the provision is not intended to compel the State to enact positive measures that would accommodate as many people as possible into public office. Moreover, the provision as written leaves much to be desired if it is to be regarded as the source of positive rights. It is difficult to interpret the clause as operative in the absence of legislation since its effective means and reach are not properly defined. Broadly written, the myriad of claims that can be subsumed under this rubric appear to be entirely open-ended. Words and phrases such as "equal access," "opportunities," and "public service" are susceptible to countless interpretations owing to their inherent impreciseness. Certainly, it was not the intention of the framers to inflict on the people an operative but amorphous foundation from which innately unenforceable rights

may be sourced. The privilege of equal access to opportunities to public office may be subjected to limitations. Some valid limitations specifically on the privilege to seek elective office are found in the provisions of the Omnibus Election Code on "Nuisance Candidates. As long as the limitations apply to everybody equally without discrimination, however, the equal access clause is not violated. Equality is not sacrificed as long as the burdens engendered by the limitations are meant to be borne by any one who is minded to file a certificate of candidacy. In the case at bar, there is no showing that any person is exempt from the limitations or the burdens which they create. The rationale behind the prohibition against nuisance candidates and the disqualification of candidates who have not evinced a bona fide intention to run for office is easy to divine. The State has a compelling interest to ensure that its electoral exercises are rational, objective, and orderly. Towards this end, the State takes into account the practical considerations in conducting elections. Inevitably, the greater the number of candidates, the greater the opportunities for logistical confusion, not to mention the increased allocation of time and resources in preparation for the election. The organization of an election with bona fide candidates standing is onerous enough. To add into the mix candidates with no serious intentions or capabilities to run a viable campaign would actually impair the electoral process. This is not to mention the candidacies which are palpably ridiculous so as to constitute a onenote joke. The poll body would be bogged by irrelevant minutiae covering every step of the electoral process, most probably posed at the instance of these nuisance candidates. It would be a senseless sacrifice on the part of the State. The question of whether a candidate is a nuisance candidate or not is both legal and factual. The basis of the factual determination is not before this Court. Thus, the remand of this case for the reception of further evidence is in order. The SC remanded to the COMELEC for the reception of further evidence, to determine the question on whether petitioner Elly Velez Lao Pamatong is a nuisance candidate as contemplated in Section 69 of the Omnibus Election Code.

Obiter Dictum: One of Pamatong's contentions was that he was an international lawyer and is thus more qualified compared to the likes of Erap, who was only a high school dropout. Under the Constitution (Article VII, Section 2), the only requirements are the following: (1) natural-born citizen of the Philippines; (2) registered voter; (3) able to read and write; (4) at least forty years of age on the day of the election; and (5) resident of the Philippines for at least ten years immediately preceding such election.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Consti Cases ReviewDocument227 pagesConsti Cases ReviewRhoan HiponiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Banc, Shall Be The Sole Judge of All Contests Relating To The Election, Returns, and Qualifications ofDocument45 pagesBanc, Shall Be The Sole Judge of All Contests Relating To The Election, Returns, and Qualifications ofGlean Myrrh ValdePas encore d'évaluation

- DigestDocument16 pagesDigestRea AlcantaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Constitutional limits on concurrent gov't appointmentsDocument25 pagesConstitutional limits on concurrent gov't appointmentsGlean Myrrh ValdePas encore d'évaluation

- Digest Lawyer'SLeaguevsAquinoDocument24 pagesDigest Lawyer'SLeaguevsAquinoGlean Myrrh Almine ValdePas encore d'évaluation

- Control Power Free Telephone Workers Union vs. OpleDocument4 pagesControl Power Free Telephone Workers Union vs. OplejohnmiggyPas encore d'évaluation

- De Leon vs. Esguerra ruling affirms security of tenure for elected barangay officialsDocument28 pagesDe Leon vs. Esguerra ruling affirms security of tenure for elected barangay officialsMari CariPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Consti 1Document14 pagesCase Digest Consti 1Honeybeez TvPas encore d'évaluation

- Calderon V CaraleDocument2 pagesCalderon V CaraleTrina Donabelle GojuncoPas encore d'évaluation

- Alliance for Alternative Action: Key Constitutional Law CasesDocument172 pagesAlliance for Alternative Action: Key Constitutional Law CasesChasz CarandangPas encore d'évaluation

- Alliance For Alternative Action: The Adonis Cases 2011Document171 pagesAlliance For Alternative Action: The Adonis Cases 2011Vince Llamazares LupangoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sec. 15 Midnight AppointmentsDocument3 pagesSec. 15 Midnight AppointmentsDawn Jessa GoPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioner vs. VS.: en BancDocument11 pagesPetitioner vs. VS.: en BancDesai SarvidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sarmiento vs. Mison, 156 SCRA 549 (1987)Document39 pagesSarmiento vs. Mison, 156 SCRA 549 (1987)Reginald Dwight FloridoPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Liberties Union VS Executive SecretaryDocument13 pagesCivil Liberties Union VS Executive SecretaryHoneybeez TvPas encore d'évaluation

- Calderon V Carale GR 91636Document13 pagesCalderon V Carale GR 91636Loranisa BalorioPas encore d'évaluation

- Quintos-Deles Vs Commission On Appointments GR No. 83216 (September 4, 1989)Document17 pagesQuintos-Deles Vs Commission On Appointments GR No. 83216 (September 4, 1989)nabingPas encore d'évaluation

- Legislative Department DigestedDocument40 pagesLegislative Department DigestedRotsen Kho YutePas encore d'évaluation

- Appointed by The President, Subject To Confirmation by The Commission On Appointments. Appointments ToDocument3 pagesAppointed by The President, Subject To Confirmation by The Commission On Appointments. Appointments ToPat GalloPas encore d'évaluation

- StatCon Case DigestsDocument11 pagesStatCon Case DigestsJay Yumang0% (1)

- Adonis Notes 2011Document169 pagesAdonis Notes 2011Ron GamboaPas encore d'évaluation

- Imbong vs Ferrer Case Digest on Constitutionality of RA 6132Document3 pagesImbong vs Ferrer Case Digest on Constitutionality of RA 6132Guillermo Olivo IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- Set 10 Case Digest Complete ConstiDocument117 pagesSet 10 Case Digest Complete ConstiMeeJeePas encore d'évaluation

- Ernesto B. Francisco, Jr. vs. The House of Representatives G.R. No. 160261. November 10, 2003Document8 pagesErnesto B. Francisco, Jr. vs. The House of Representatives G.R. No. 160261. November 10, 2003PJAPas encore d'évaluation

- Sarmiento v. MisonDocument3 pagesSarmiento v. MisonRaymond RoquePas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on appointment of Bureau of Customs CommissionerDocument24 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court rules on appointment of Bureau of Customs CommissionerFranzMordenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sarmiento v. Mison (GR L-79974, 17 December 1987)Document3 pagesSarmiento v. Mison (GR L-79974, 17 December 1987)modernbibliothecaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Constitution of The Philippines: HeldDocument16 pagesThe Constitution of The Philippines: HeldChristlen DelgadoPas encore d'évaluation

- HW Cases Political LawDocument5 pagesHW Cases Political LawVictor LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Chavez V JBCDocument4 pagesCase Digest Chavez V JBCNichole Patricia Pedriña100% (5)

- Chavez V JBC DigestDocument5 pagesChavez V JBC DigestJJ CoolPas encore d'évaluation

- Stat Con Ass2Document10 pagesStat Con Ass2EA EncorePas encore d'évaluation

- GONZALES VS. COMELEC (21 SCRA 774 G.R. No. L-28196 9 Nov 1967)Document5 pagesGONZALES VS. COMELEC (21 SCRA 774 G.R. No. L-28196 9 Nov 1967)Shanina Mae FlorendoPas encore d'évaluation

- Adonis Notes 2011Document172 pagesAdonis Notes 2011Alarice L. YangPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Case DigestsDocument172 pagesConsti Case DigestsPaolo Antonio Escalona100% (3)

- Consti Cases Review 2021Document9 pagesConsti Cases Review 2021Mary Kristin Joy GuirhemPas encore d'évaluation

- Executive Dept-Case DigestDocument26 pagesExecutive Dept-Case DigestThea Faye Buncad Cahuya100% (1)

- Pubof CasesDocument28 pagesPubof CasesZach Matthew GalendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Imbong Vs Ferrer Case DigestDocument14 pagesImbong Vs Ferrer Case DigestAnonymous zIDJz7Pas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 79974 December 17, 1987Document32 pagesG.R. No. 79974 December 17, 1987Tashi MariePas encore d'évaluation

- CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY 1Document5 pagesCIVIL LIBERTIES UNION V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY 1Christian AribasPas encore d'évaluation

- GR 91636Document13 pagesGR 91636AM CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Liberties Union V Executive Secretary (194 SCRA 317) Francisco vs. House of Representatives (GR 160261, 10 November 2003)Document7 pagesCivil Liberties Union V Executive Secretary (194 SCRA 317) Francisco vs. House of Representatives (GR 160261, 10 November 2003)GracePas encore d'évaluation

- Today Is Friday, July 17, 2015: Gold Creek Mining Corp. vs. RodriguezDocument7 pagesToday Is Friday, July 17, 2015: Gold Creek Mining Corp. vs. RodriguezIan InandanPas encore d'évaluation

- Issue:: Gonzales vs. ComelecDocument10 pagesIssue:: Gonzales vs. ComelecblimjucoPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 2 - EXECUTIVE TO JUDICIARYDocument7 pagesGroup 2 - EXECUTIVE TO JUDICIARYGlean Myrrh ValdePas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez v. JBC - Gr. No. 202242Document9 pagesChavez v. JBC - Gr. No. 202242Jm BrjPas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez v. JBC: Composition of Judicial Appointments CouncilDocument6 pagesChavez v. JBC: Composition of Judicial Appointments CouncilPaolo AlarillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bautista vs Salonga CaseDocument3 pagesBautista vs Salonga CaseJessamine OrioquePas encore d'évaluation

- 022 BUNALES PhilConSa vs. GimenezDocument2 pages022 BUNALES PhilConSa vs. GimenezCarissa CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- FRANCISCO I. CHAVEZ, Petitioner, Judicial and Bar Council, Sen. Francis Joseph G. Escudero and Rep. Niel C. TUPAS, JR., Respondents. FactsDocument5 pagesFRANCISCO I. CHAVEZ, Petitioner, Judicial and Bar Council, Sen. Francis Joseph G. Escudero and Rep. Niel C. TUPAS, JR., Respondents. FactsChristine LarogaPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Chavez v. JBC, July 17, 2012Document41 pages3 Chavez v. JBC, July 17, 2012GERALD LUDASPas encore d'évaluation

- Facts:: First, The Heads of The Executive Departments, Ambassadors, Other PublicDocument3 pagesFacts:: First, The Heads of The Executive Departments, Ambassadors, Other Publicknicky FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases Atty Arellano-MidtermsDocument17 pagesCases Atty Arellano-MidtermsOna MaePas encore d'évaluation

- Chavez Vs JBCDocument4 pagesChavez Vs JBCIyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Address at Oregon Bar Association annual meetingD'EverandAddress at Oregon Bar Association annual meetingPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33D'EverandHuman Rights in the Indian Armed Forces: An Analysis of Article 33Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestsDocument209 pagesCase DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neypes RuleDocument6 pagesThe Neypes RuleEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Employer-Employee Relationship CasesDocument190 pagesEmployer-Employee Relationship CasesEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- LABOR ChanRoblesDocument52 pagesLABOR ChanRoblesEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments Law OutlineDocument7 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law OutlineEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Loon vs. Power MasterDocument2 pagesLoon vs. Power MasterEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- PilDocument32 pagesPilEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4th Set LabRelDocument13 pages4th Set LabRelEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Torts Memory Aid AteneoDocument11 pagesTorts Memory Aid AteneoStGabriellePas encore d'évaluation

- Employer-Employee Relationship CasesDocument190 pagesEmployer-Employee Relationship CasesEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of DesistanceDocument1 pageAffidavit of DesistanceEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporation Code OutlineDocument8 pagesCorporation Code OutlineEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- NLRC Rules of Procedure 2011Document30 pagesNLRC Rules of Procedure 2011Angela FeliciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary of PleadingsDocument1 pageSummary of PleadingsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- NLRC Ruling on Illegal Dismissal UpheldDocument22 pagesNLRC Ruling on Illegal Dismissal UpheldEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transportation LawDocument150 pagesTransportation Lawjum712100% (3)

- Philippines Corporation CodeDocument68 pagesPhilippines Corporation CodeEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes in Corporation LawDocument47 pagesNotes in Corporation LawEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Transpo 16 - 20Document119 pagesTranspo 16 - 20Eloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Amp AtuanDocument8 pagesAmp AtuanEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ampatuan Case DigestDocument3 pagesAmpatuan Case DigestEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Batch of Consti DigestsDocument56 pages1st Batch of Consti DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Amp AtuanDocument8 pagesAmp AtuanEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Commendador vs. de VillaDocument1 pageCommendador vs. de VillaEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- NEGO Case DigestsDocument4 pagesNEGO Case DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- NEGO Case DigestsDocument4 pagesNEGO Case DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Education Science Tachnology Arts Culture SportsDocument103 pagesEducation Science Tachnology Arts Culture SportsEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Property Case Digests 1Document8 pagesProperty Case Digests 1Eloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Law IDocument925 pagesConsti Law IEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Philippines As A StateDocument263 pagesThe Philippines As A StateEloisa Katrina MadambaPas encore d'évaluation

- MIKE A. FERMIN v. ATTY. LINTANG H. BEDOLDocument6 pagesMIKE A. FERMIN v. ATTY. LINTANG H. BEDOLsejinmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ladlad PartylistDocument10 pagesLadlad PartylistLennom EspirituPas encore d'évaluation

- New Normal ManualDocument1 276 pagesNew Normal ManualGMA News OnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Marcos vs. Comelec Digest 1Document2 pagesMarcos vs. Comelec Digest 1Rochelle Ann Reyes50% (2)

- Garcillano v. HOP G.R. No. 170338 December 23, 2008Document4 pagesGarcillano v. HOP G.R. No. 170338 December 23, 2008Emrico CabahugPas encore d'évaluation

- TibagDocument48 pagesTibagAngelika CalingasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Imbong v. COMELEC DigestDocument2 pagesImbong v. COMELEC DigestKatrYna JaponaPas encore d'évaluation

- TALAGADocument66 pagesTALAGAChingPas encore d'évaluation

- Election Law 101 SyllabusDocument9 pagesElection Law 101 SyllabusRalph Ryan TooPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Digest Legal EthicsDocument12 pagesCase Digest Legal EthicsPew IcamenPas encore d'évaluation

- Commission On Elections: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument676 pagesCommission On Elections: Republic of The PhilippinesGirly A. MacaraegPas encore d'évaluation

- Santiago vs. Comelec, 270 Scra 106Document20 pagesSantiago vs. Comelec, 270 Scra 106Krisleen AbrenicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Uapsa Mapua BylawsDocument29 pagesUapsa Mapua Bylawsuapsa.mapua.codoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Case Digests FinalsDocument7 pagesConsti Case Digests FinalsFe Myra LagrosasPas encore d'évaluation

- University of Santo Tomas Senior High School Commission On Elections Executive Order No. 03 Series of 2018-2019Document7 pagesUniversity of Santo Tomas Senior High School Commission On Elections Executive Order No. 03 Series of 2018-2019Isaiah CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Domado Disomimba Sultan vs. Atty. Casan MacabandingDocument8 pagesDomado Disomimba Sultan vs. Atty. Casan MacabandingAnonymous dtceNuyIFIPas encore d'évaluation

- Lokin v. COMELECDocument2 pagesLokin v. COMELECCJ MillenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Antonio Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesAntonio Vs ComelecEmmanuel C. DumayasPas encore d'évaluation

- Fornier v. COMELEC and Ronald Allan Kelley PoeDocument3 pagesFornier v. COMELEC and Ronald Allan Kelley PoeAnne Janelle Guan100% (3)

- Technology For Teaching and Learning 1Document3 pagesTechnology For Teaching and Learning 1ChefcelinePas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Digest 06-24-2016Document127 pagesConsti Digest 06-24-2016Careyssa MaePas encore d'évaluation

- Demafiles Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesDemafiles Vs ComelecRian Lee TiangcoPas encore d'évaluation

- 18 Comelec V Noynay DigestDocument2 pages18 Comelec V Noynay Digestclovis_contadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Abayon Vs HRET and DazaDocument13 pagesAbayon Vs HRET and DazaKael MarmaladePas encore d'évaluation

- Consti Law 1 Syllabus PDFDocument59 pagesConsti Law 1 Syllabus PDFverlyn ocretoPas encore d'évaluation

- Petitioner,: en Banc Civil Service Commission, G.R. No. 158791Document39 pagesPetitioner,: en Banc Civil Service Commission, G.R. No. 158791Ynna GesitePas encore d'évaluation

- Cayetano V Monsod - GR 100113 - Gilberto B. MirabuenaDocument1 pageCayetano V Monsod - GR 100113 - Gilberto B. Mirabuenashienna baccayPas encore d'évaluation

- CD - 14. Faelnar Vs PeopleDocument1 pageCD - 14. Faelnar Vs PeopleCzarina CidPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus LocGov Election RevDocument7 pagesSyllabus LocGov Election RevkdescallarPas encore d'évaluation

- Election Contests & Quo Warranto ActionsDocument14 pagesElection Contests & Quo Warranto ActionsBruce EstillotePas encore d'évaluation