Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Derivatives

Transféré par

Sheetal IyerCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Derivatives

Transféré par

Sheetal IyerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A derivative is a financial instrument whose value is based on one or more under lying assets.

In practice, it is a contract between two parties that specifies c onditions (especially the dates, resulting values of the underlying variables, a nd notional amounts) under which payments are to be made between the parties.[1] [2] The most common types of derivatives are: forwards, futures, options, and sw aps. The most common underlying assets include: commodities, stocks, bonds, inte rest rates and currencies. Under US law and the laws of most other developed countries, derivatives have sp ecial legal exemptions that make them a particularly attractive legal form to ex tend credit.[3] The strong creditor protections afforded to derivatives counterp arties, in combination with their complexity and lack of transparency however, c an cause capital markets to underprice credit risk. This can contribute to credi t booms, and increase systemic risks.[3] Indeed, the use of derivatives to conce al credit risk from third parties while protecting derivative counterparties con tributed to the financial crisis of 2008 in the United States.[3][4] Financial reforms within the US since the financial crisis have served only to r einforce special protections for derivatives, including greater access to govern ment guarantees, while minimizing disclosure to broader financial markets.[5] Usage Derivatives are used by investors for the following: provide leverage (or gearing), such that a small movement in the underlying valu e can cause a large difference in the value of the derivative;[8] speculate and make a profit if the value of the underlying asset moves the way t hey expect (e.g., moves in a given direction, stays in or out of a specified ran ge, reaches a certain level); hedge or mitigate risk in the underlying, by entering into a derivative contract whose value moves in the opposite direction to their underlying position and ca ncels part or all of it out;[9] obtain exposure to the underlying where it is not possible to trade in the under lying (e.g., weather derivatives);[10] create option ability where the value of the derivative is linked to a specific condition or event (e.g. the underlying reaching a specific price level). [edit]Hedging Derivatives allow risk related to the price of the underlying asset to be transf erred from one party to another. For example, a wheat farmer and a miller could sign a futures contract to exchange a specified amount of cash for a specified a mount of wheat in the future. Both parties have reduced a future risk: for the w heat farmer, the uncertainty of the price, and for the miller, the availability of wheat. However, there is still the risk that no wheat will be available becau se of events unspecified by the contract, such as the weather, or that one party will renege on the contract. Although a third party, called a clearing house, i nsures a futures contract, not all derivatives are insured against counter-party risk. From another perspective, the farmer and the miller both reduce a risk and acqui re a risk when they sign the futures contract: the farmer reduces the risk that the price of wheat will fall below the price specified in the contract and acqui res the risk that the price of wheat will rise above the price specified in the contract (thereby losing additional income that he could have earned). The mille r, on the other hand, acquires the risk that the price of wheat will fall below the price specified in the contract (thereby paying more in the future than he o therwise would have) and reduces the risk that the price of wheat will rise abov e the price specified in the contract. In this sense, one party is the insurer ( risk taker) for one type of risk, and the counter-party is the insurer (risk tak er) for another type of risk. Hedging also occurs when an individual or institution buys an asset (such as a c ommodity, a bond that has coupon payments, a stock that pays dividends, and so o n) and sells it using a futures contract. The individual or institution has acce ss to the asset for a specified amount of time, and can then sell it in the futu

re at a specified price according to the futures contract. Of course, this allow s the individual or institution the benefit of holding the asset, while reducing the risk that the future selling price will deviate unexpectedly from the marke t's current assessment of the future value of the asset. Derivatives traders at the Chicago Board of Trade Derivatives can serve legitimate business purposes. For example, a corporation b orrows a large sum of money at a specific interest rate.[11] The rate of interes t on the loan resets every six months. The corporation is concerned that the rat e of interest may be much higher in six months. The corporation could buy a forw ard rate agreement (FRA), which is a contract to pay a fixed rate of interest si x months after purchases on a notional amount of money.[12] If the interest rate after six months is above the contract rate, the seller will pay the difference to the corporation, or FRA buyer. If the rate is lower, the corporation will pa y the difference to the seller. The purchase of the FRA serves to reduce the unc ertainty concerning the rate increase and stabilize earnings. [edit]Speculation and arbitrage Derivatives can be used to acquire risk, rather than to hedge against risk. Thus , some individuals and institutions will enter into a derivative contract to spe culate on the value of the underlying asset, betting that the party seeking insu rance will be wrong about the future value of the underlying asset. Speculators look to buy an asset in the future at a low price according to a derivative cont ract when the future market price is high, or to sell an asset in the future at a high price according to a derivative contract when the future market price is low. Individuals and institutions may also look for arbitrage opportunities, as when the current buying price of an asset falls below the price specified in a future s contract to sell the asset. Speculative trading in derivatives gained a great deal of notoriety in 1995 when Nick Leeson, a trader at Barings Bank, made poor and unauthorized investments i n futures contracts. Through a combination of poor judgment, lack of oversight b y the bank's management and regulators, and unfortunate events like the Kobe ear thquake, Leeson incurred a US$1.3 billion loss that bankrupted the centuries-old institution.[13]

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- New Testament Student Manual EngDocument929 pagesNew Testament Student Manual EngSheetal Iyer100% (1)

- Work Flow 2Document2 pagesWork Flow 2Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- 9Document1 page9Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- E - Forms MappingDocument3 pagesE - Forms MappingSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Report Sheetal Iyer 1Document6 pagesReport Sheetal Iyer 1Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Voluntary CutsDocument1 pageVoluntary CutsSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- ReportDocument16 pagesReportSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Report Sheetal Iyer 1Document6 pagesReport Sheetal Iyer 1Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- AdyCover PageDocument1 pageAdyCover PageSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhirubhai Ambani: If You Work With Determination and With Perfection, Success Will FollowDocument1 pageDhirubhai Ambani: If You Work With Determination and With Perfection, Success Will FollowSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Hello SirDocument1 pageHello SirSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Attributes ExplainedDocument3 pagesAttributes ExplainedSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Thank you for your thoughtful giftDocument1 pageThank you for your thoughtful giftSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Sr. No. Pg. NoDocument1 pageSr. No. Pg. NoSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- R C A S C: Oyal Ollege of RTS, Cience & OmmerceDocument1 pageR C A S C: Oyal Ollege of RTS, Cience & OmmerceSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- ACKNOWDocument5 pagesACKNOWSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Eligibility criteria and investment routes for FIIs seeking Indian registrationDocument4 pagesEligibility criteria and investment routes for FIIs seeking Indian registrationSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Compiled byDocument1 pageCompiled bySheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 4Document12 pagesChapter 4Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Compiled By111Document1 pageCompiled By111Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- R C A S C: Oyal Ollege of RTS, Cience & OmmerceDocument1 pageR C A S C: Oyal Ollege of RTS, Cience & OmmerceSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- QUESTIONSDocument2 pagesQUESTIONSSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- FII ProcedureDocument13 pagesFII ProcedureSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- WtoDocument40 pagesWtoSheetal Iyer100% (1)

- FYBCom 121Document5 pagesFYBCom 121Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview ITDocument1 pageOverview ITSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- EmsDocument4 pagesEmsSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

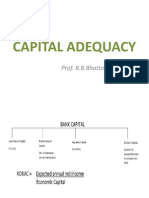

- Capital Adequacy: Prof. B.B.BhattacharyyaDocument115 pagesCapital Adequacy: Prof. B.B.BhattacharyyaSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- PnL Analysis of Options Strategy as Nifty Moves 57-6000Document12 pagesPnL Analysis of Options Strategy as Nifty Moves 57-6000Sheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation

- Option PricingDocument11 pagesOption PricingSheetal IyerPas encore d'évaluation