Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Candidacy

Transféré par

Monefah MulokCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Candidacy

Transféré par

Monefah MulokDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

December 19, 2012 Topic: Candidacy Group 3 Palle, Ira Jane Y. Puyales, Mannylyn J.

I.

Eligibility of Candidates a. Qualifications (President & V-President, Congress, Local Elective Officials) i. Citizenship Requirement ii. Residence iii. Drug Testing b. Grounds for disqualification i. Sec 12 & 68 of the Omnibus Election Code ii. Sec 40 of the Local Government Code iii. Sec 4 Lone Candidate Law (Special Disqualifications) c. Jurisdiction d. Petitions i. Petition to deny due course or cancel certificate of candidacy ii. Petition for disqualification iii. Distinguish Both Petitions e. Effects of Disqualification II. Filing of Certificate of Candidacy a. Candidate Defined b. Purpose c. Mode of Filing d. Time of Filing e. Place of Filing f. Prohibition Against Filing of Multiple Candidacies g. Contents of Certificate of Candidacy h. Correction of Certificate i. Effect of Filing j. Nuisance Candidates i. Grounds for Declaration of nuisance Candidacy ii. Nature of Proceedings iii. Procedure for Declaration of Candidate as Nuisance k. Guest Candidates l. Withdrawal of Certificate of Candidacy m. Substitution of Candidates III. Political Parties a. Definition b. Registration i. Purpose ii. Procedure c. Disqualification d. Grounds for cancellation

ELIGIBILITY OF CANDIDATES A. QUALIFICATIONS(President & V-President, Congress, Local Elective Officials) President and Vice-President of the Philippines Section 63 of the Omnibus Election Code (OEC for brevity) in line with Article VII, Section 2 and 3 of the 1987 Constitution set forth the qualification that is needed to be attained by a person who seeks to be elected as President and Vice-President. Sec. 63 OEC No person may be elected President or Vice President unless he is a natural born citizen of the Philippines, a registered voter, able to read and write, at least forty years of age on the day of the election, and a resident of the Philippines for at least ten years immediately preceding such election. Congress Section 64 of the Omnibus Election Code provides for the qualification for Members of the Batasang Pambansa. It states that: No person shall be elected Member of the Batasang Pambansa as provincial, city or district representative unless he is a natural-born citizen of the Philippines and, on the day of the election, is at least twenty-five years of age, able to read and write, a registered voter in the constituency in which he shall be elected, and a resident thereof for a period of not less than six months immediately preceding the day of the election. A sectoral representative shall be a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, able to read and write, a resident of the Philippines, able to read and write, a resident of the Philippines for a period of not less than one year immediately preceding the day of the election, a bona fide member of the sector he seeks to represent, and in the case of a representative of the agricultural or industrial labor sector, shall be a registered voter, and on the day of the election is at least twenty-five years of age. The youth sectoral representative should at least be eighteen and not be more than twenty-five years of age on the day of the election: Provided, however, that any youth sectoral representative who attains the age of twenty-five years during his term shall be entitled to continue in office until the expiration of his term. However, Section 64 of Omnibus Election Code is modified by Article VI, Section 3 and 6 of the 1987 Constitution which provides that Article VI, Section 3 No person shall be a Senator unless he is a natural -born citizen of the Philippines, and, on the day of the election, is at least thirty-five years of age, able to read and write, a registered voter, and a resident of the Philippines for not less than two years immediately preceding the day of the election. Article VI, Section 6 No person shall be a Member of the House of Representatives unless he is a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, and, on the day of the election, is at least twenty-five years of age, able to read and write, and, except the party-list representatives, a registered voter in the district in

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

which he shall be elected, and a resident thereof for not less than one year immediately preceding the day of the election. Local Elective Official Section 65 of the Omnibus Code of the Philippines provides that: The qualifications for elective provincial, city, municipal and barangay officials shall be those provided for in the Local Government Code. Section 39 of the Local Government Code provides the qualifications for the elective local officials. (a) An elective local official must be a citizen of the Philippines; a registered voter in the barangay, municipality, city, or province or, in the case of a member of the sangguniang panlalawigan, sangguniang panlungsod, or sanggunian bayan, the district where he intends to be elected; a resident therein for at least one (1) year immediately preceding the day of the election; and able to read and write Filipino or any other local language or dialect. Candidates for the position of governor, vice- governor or member of the sangguniang panlalawigan, or Mayor, vice-mayor or member of the sangguniang panlungsod of highly urbanized cities must be at least twenty-three (23) years of age on election day. Candidates for the position of Mayor or vice-mayor of independent component cities, component cities, or municipalities must be at least twenty-one (21) years of age on election day. Candidates for the position of member of the sangguniang panlungsod or sangguniang bayan at least eighteen (18) years of age on election day. Candidates for the position of punong barangay or member of the sangguniang barangay must be at least eighteen (18) years of age on election day. Candidates for the sangguniang kabataan must be at least fifteen (15) years of age but not more than twenty-one (21) years of age on election day. Citizenship Requirement:

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

I.

Who are citizens of the Philippines? Citizens of the Philippines provided for by Article IV, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution are the following: 1. Those who are citizens of the Philippines at the time of the adoption of this Constitution; 2. Those whose fathers or mothers are citizens of the Philippines; 3. Those born before January 17, 1973, of Filipino mothers, who elect Philippine citizenship upon reaching the age of majority; and 4. Those who are naturalized in the accordance with law.

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

It further provides in Article IV, Sec 4 of the 1987 Constitution that: Citizens of the Philippines who marry aliens shall retain their citizenship, unless by their act or omission they are deemed, under the law, to have renounced it.

Who are the Natural-Born Citizens? Natural-born citizens are those who are citizens of the Philippines from birth without having to perform any act to acquire or perfect their Philippine citizenship. Those who elect Philippine citizenship in accordance with paragraph (3), Section 1 hereof shall be deemed natural-born citizens. 1987 Constitution, Article IV, Section 2 CASE 1: CO vs HRET G.R. No. 92191-92 July 30, 1991 FACTS: Petitioner Antonio Co ran for Congressman of the 2nd District of Samar. Private respondent Jose Ong, Jr. was declared winner. Although Ongs mother is a natural born -Filipina, his father was only naturalized as a Filipino when the respondent was already nine years old. Given these facts, petitioner contends that Ong is not a natural-born Filipino citizen and therefore disqualified from being elected Congressman. ISSUE: WON Ong is a natural-born Filipino citizen. RULING: Affirmative. Section 15 of the Revised Naturalization Act squarely applies its benefit to him for he was then a minor residing in this country. The Courts based its resolution of the issue by tracing Jose Ong, Jr. citizenship to his mother who was a natural-born Filipina. What is material to the case is whether he elected Filipino citizenship when he reached the age of majority as provided for by Section 1 (4) Article IV of the 1935 Constitution which was the operative law when he was born. Under the 1987 Constitution, natural-born status can only be accorded to individuals who elected citizenship upon reaching majority. In the opinion of the Court it is not necessary for Ong, Jr. to formally or in writing elect citizenship when he came of age as he was already a citizen since he was nine by virtue of his mother being a natural-born citizen and his father a naturalized Filipino. Dual Citizen Dual citizenship arises when, as a result of the concurrent application of the different laws of two or more states, a person is simultaneously considered a national by the state. This status of citizenship does not serve as a disqualification because a person on this case is ipso facto and without any voluntary act on his part is considered a citizen of both states. However, what is prohibited is dual allegiance, where it is subject to strict process with respect to the termination of the status. In dual citizenship, the act of filing their certificate of candidacy, they already elected Philippines citizenship, thus, terminating their status as a person with dual citizenship.

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

CASE 2: VALLES v. COMELEC G.R. No. 137000, August 9, 2000 FACTS: Respondent was born in Australia to a Filipino father and an Australian mother. Australia follows jus soli. She ran for governor. Opponent filed petition to disqualify her on the ground of dual citizenship. HELD: Dual citizenship as a disqualification refers to citizens with dual allegiance. The fact that she has dual citizenship does not automatically disqualify her from running for public office. Filing a certificate of candidacy suffices to renounce foreign citizenship because in the certificate, the candidate declares himself to be a Filipino citizen and that he will support the Philippine Constitution. Such declaration operates as an effective renunciation of foreign citizenship. Repatriation Repatriation simply consists of the taking of an oath of allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines and registering said oath in the Local Civil Registry of the place where the person concerned resides or last resided. Repatriation may be had under various statutes by those who lost their citizenship due to: (1) desertion of the armed forces; (2) service in the armed forces of the allied forces in World War II; (3) service in the Armed Forces of the United States at any other time; (4) marriage of a Filipino woman to an alien; and (5) political and economic necessity. Repatriation results in the recovery of what had been lost. When what was lost is natural born citizenship, what is recovered is also natural born citizenship. CASE 3: BENGZON V. CRUZ, GR. NO. 142840, MAY 7, 2001 Facts: Bengzon, incumbent congressman for the 2nd District of Pangasinan, was defeated by respondent Teodoro C. Cruz in the elections of May 11, 1998. Cruz was a natural-born Filipino citizen, but he took the oath of allegiance to the United States on November 5, 1985, and was naturalized as a U.S. citizen on June 5, 1990. On March 17, 1994, he retook his Philippine citizenship in accordance with RA 2630. Petitioner asserts that respondent is no longer a natural-born citizen and therefore disqualified from running as a congressman. Issue: Whether or not Cruz was a natural-born citizen. Held: Yes. It is apparent from the enumeration of who are citizens under the present Constitution that there are only two classes of citizens: (1) those who are natural-born and (2) those who are naturalized in accordance with law. A citizen who is not a naturalized Filipino, i.e., did not have to undergo the process of naturalization to obtain Philippine citizenship, necessarily is natural-born Filipino. Noteworthy is the absence in said enumeration of a

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

separate category for persons who, after losing Philippine citizenship, subsequently reacquire it. The reason therefor is clear: as to such persons, they would either be naturalborn or naturalized depending on the reasons for the loss of their citizenship and the mode prescribed by the applicable law for the reacquisition thereof. As respondent Cruz was not required by law to go through naturalization proceeding in order to reacquire his citizenship, he is perforce a natural-born Filipino. As such, he possessed all the necessary qualifications to be elected as member of the House of Representatives. II. Residence Requirement

Residence for the purposes of qualification for an elective position is synonymous with domicile. Within the view of Constitution regarding election process, residence equates domicile. Article 50 of the Civil Code states that for the exercise of civil rights, and the fulfillment of civil obligations, the domicile of natural persons is their place of habitual residence. Domicile means and individuals permanent home, a place to which, whenever absent for business or for pleasure, one intends to return, and depends on facts and circumstances, in the sense that they disclose intent. A domicile, once acquired is retained until a new one is gained. To successfully effect such change, it must demonstrate (a) an actual removal or an actual change of domicile; (b) a bona fide intention of abandoning the former place of residence and establishing a new one; and (3) acts which correspond with the purpose. In other words, there must basically be animus manendi coupled with animus non-revertendi. Domicile Twin Element CASE 4: ROMUALDEZ-MARCOS vs. COMELEC 248 SCRA 300 FACTS: Marcos, filed her certificate of candidacy for the position of Representative of Leyte First District. On March 23, 1995, private respondent Cirilio Montejo, also a candidate for the same position, filed a petition for disqualification of the petitioner with COMELEC on the ground that petitioner did not meet the constitutional requirement for residency. On March 29, 1995, petitioner filed an amended certificate of candidacy, changing the entry of seven months to since childhood in item no. 8 in said certi ficate. However, the amended certificate was not received since it was already past deadline. She claimed that she always maintained Tacloban City as her domicile and residence. The Second Division of the COMELEC with a vote of 2 to 1 came up with a resolu tion finding private respondents petition for disqualification meritorious. ISSUE: Whether or not petitioner lost her domicile of origin by operation of law as a result of her marriage to the late President Marcos. HELD: For election purposes, residence is used synonymously with domicile. The Court upheld the qualification of petitioner, despite her own declaration in her certificate of candidacy that she had resided in the district for only 7 months, because of the following: (a) a minor

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

follows the domicile of her parents; Tacloban became petitioners domicile of origin by operation of law when her father brought the family to Leyte; (b) domicile of origin is lost only when there is actual removal or change of domicile, a bona fide intention of abandoning the former residence and establishing a new one, and acts which correspond with the purpose; in the absence of clear and positive proof of the concurrence of all these, the domicile of origin should be deemed to continue; (c) the wife does not automatically gain the husbands domicile because the term residence in Civil Law does not mean the same thing in Political Law; when petitioner married President Marcos in 1954, she kept her domicile of origin and merely gained a new home, not a domicilium necessarium; (d) even assuming that she gained a new domicile after her marriage and acquired the right to choose a new one only after her husband died, her acts following her return to the country clearly indicate that she chose Tacloban, her domicile of origin, as her domicile of choice. DOMICILE includes the twin elements of: (1) The fact of residing or physical presence in a fixed place; (2) Animus manendi, or the intention of returning there permanently. Classification of Domicile CASE 5: UGDORACION, JR. vs COMELEC, GR No. 179851, April 18, 2008 FACTS: Jose Ugdoracion and Ephraim Tungol were rival mayoralty candidates in Albuquerque, Bohol in the May 2007 elections. Tungol filed a petition to cancel Ugdoracions Certif icate of Candidacy contending that the latters declaration of eligibility for Mayor constituted material misrepresentation; that he is actually a green card holder or a permanent resident of the US. It appears that Ugdoracion became a permanent US resident on September 26, 2001 and was issued an Alien Number by the USINS. Ugdoracion, on the other hand, presented the following documents as proof of his substantial compliance with the residency requirement: (1) a residence certificate; (2) an application f or a new voters registration; and (3) a photocopy of Abandonment of Lawful Permanent Resident Status. COMELEC cancelled Ugdoracions COC and removed his name from the certified list of candidates for Mayor. His motion for recon was denied. Hence, the petition imputing grave abuse of discretion to the COMELEC. ISSUE Whether Ugdoracion lost his domicile of origin HELD: YES. Residence, in contemplation of election laws, is synonymous to domicile. Domicile is the place where one actually or constructively has his permanent home, where he, no matter where he may be found at any given time, eventually intends to return ( animus revertendi) and remain(animus manendi). Domicile is classified into (1) domicile of origin, which is acquired by every person at birth; (2)domicile of choice, which is acquired upon abandonment of the domicile of origin; and (3)domicile by operation of law, which the law attributes to a person

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

independently of his residence or intention. III. DRUG TEST R.A. No. 9165 (Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002), Section 36 (g) provides that all candidates for public office whether appointed or elected both in the national and local government shall undergo mandatory drug tests. COMELEC Resolution No. 6486, issued on December 23, 2003, implementing the RA 9365 provides that results should be submitted by the candidates for national and local position on date required by law including House of Representatives and nominees for the party-list or sectoral organizations under the party list system. The tests can be taken only in government forensic laboratories or laboratories accredited by the Department of Health. The lists will be published in two newspapers of general circulation within a week thereafter. The resolution does not indicate whether or not candidates who test positive for drugs will be allowed to assume office if they win. B. GROUNDS FOR DISQUALIFICATIONS i. Sec 12 & 68 of the Omnibus Election Code Any person who has been declared by competent authority insane or incompetent, or has been sentenced by final judgment for subversion, insurrection, rebellion or for any offense for which he has been sentenced to a penalty of more than eighteen months or for a crime involving moral turpitude, shall be disqualified to be a candidate and to hold any office, unless he has been given plenary pardon or granted amnesty. This disqualifications to be a candidate herein provided shall be deemed removed upon the declaration by competent authority that said insanity or incompetence had been removed or after the expiration of a period of five years from his service of sentence, unless within the same period he again becomes disqualified. Sec 12, Omnibus Election Code Any candidate who, in an action or protest in which he is a party is declared by final decision of a competent court guilty of, or found by the Commission of having (a) given money or other material consideration to influence, induce or corrupt the voters or public officials performing electoral functions; (b) committed acts of terrorism to enhance his candidacy; (c) spent in his election campaign an amount in excess of that allowed by this Code; (d) solicited, received or made any contribution prohibited under Sections 89, 95, 96, 97 and 104; or (e) violated any of Sections 80, 83, 85, 86 and 261, paragraphs d, e, k, v, and cc, subparagraph 6, shall be disqualified from continuing as a candidate, or if he has been elected, from holding the office. Any person who is a permanent resident of or an immigrant to a foreign country shall not be qualified to run for any elective office under this Code, unless said person has waived his status as permanent resident or immigrant of a foreign country in accordance with the residence requirement provided for in the election laws. Sec 68, Omnibus Election Code

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

A person who is disqualified under Section 68 is prohibited to continue as a candidate. A petition for disqualification requires merely the determination of whether the respondent committed acts to merit his disqualification from office, and is done through an administrative proceeding which is summary in character and requires only a clear preponderance of evidence. (Domingo vs COMELEC, 313 SCRA 311)

CASE 6: BLANCO vs COMELEC, G.R. No. 180164, June 17, 2008) FACTS: Blanco was disqualified in an administrative proceeding to run for mayor of Bulacan in May 8, 1995 elections for vote buying in violation of Section 68 of the Omnibus Election Code. During the May 14, 2007 elections, petitioner ran anew for the mayoralty position, and again, was disqualified by the COMELEC pursuant to Section 40(b) of the Local Government Code for having been removed from office as a result of administrative case. ISSUE: Whether or not Blanco is disqualified to run for an elective office HELD: No. COMELEC erred in its decision because removal from office entails the ouster of an incumbent before the expiration of his term. Petitioner never held office because his proclamation was stopped. Hence, he was disqualified only in so far as May 8, 1995 election is concerned.

ii. Sec 40 of the Local Government Code The following persons are disqualified from running for any elective local position: (a) Those sentenced by final judgment for an offense involving moral turpitude or for an offense punishable by one (1) year or more of imprisonment, within two (2) years after serving sentence; (b) Those removed from office as a result of an administrative case; (c) Those convicted by final judgment for violating the oath of allegiance to the Republic; (d) Those with dual citizenship; (e) Fugitives from justice in criminal or nonpolitical cases here or abroad; (f) Permanent residents in a foreign country or those who have acquired the right to reside abroad and continue to avail of the same right after the effectivity of this Code; and (g) The insane or feeble-minded. iii. Special Disqualification Under the Lone Candidate Law (Sec. 4, R.A 8295) In addition to the disqualifications mentioned in Sections 12 and 68 of the Omnibus Election Code and Section40 of Republic Act No. 7160, otherwise known as the Local Government Code, whenever the evidence of guilt is strong, the

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

following persons are disqualified to run in a special election called to fill the vacancy in an elective office, to wit: a) Any elective official who has resigned from his office by accepting an appointive office or for whatever reason which he previously occupied but has caused to become vacant due to his resignation; and b) Any person who, directly or indirectly, coerces, bribes, threatens, harasses, intimidates or actually causes, inflicts or produces any violence, injury, punishment, torture, damage, loss or disadvantage to any person or persons aspiring to become a candidate or that of the immediate member of his family, his honor or property that is meant to eliminate all other potential candidate. C. JURISDICTION Article IX C, Section 2, Number 2 of the 1987 Constitution gives the COMELEC the power to exercise exclusive original jurisdiction over all contests relating to the elections, returns, and qualifications of all elective regional, provincial, and city officials, and appellate jurisdiction over all contests involving elective municipal officials decided by trial courts of general jurisdiction, or involving elective barangay officials decided by trial courts of limited jurisdiction. Decisions, final orders, or rulings of the Commission on election contests involving elective municipal and barangay offices shall be final, executory, and not appealable. COMELEC has been given judicial power as judge with exclusive original jurisdiction over all contest relating to the election, returns, and qualifications of all elective regional, provincial, and city officials, and appellate jurisdiction over all contests involving elective municipal officials decided by trial courts of general jurisdiction, or involving elective barangay officials decided by trial courts of limited jurisdiction. COMELEC also have jurisdiction to issue writs of certiorari, mandamus, quo warranto or habeas corpus but only in aid of its appellate jurisdiction over election protest cases involving elective municipal officials decided by courts of general jurisdiction. (Relampagos vs Cumba) Be it noted that in the case of Galido vs. COMELEC, 193 SCRA 78, the Supreme court ruled that the final orders of the Commission on Elections in contests involving elective municipal and barangay offices are final, executory and not appealable, does not preclude a recourse to the Supreme Court by way of a special civil action of certiorari. The jurisdiction of the COMELEC over a petition to deny due course to or cancel certificates of candidacy continues even after election, if no final judgment of disqualification is rendered before the election, and the candidate facing disqualification is voted for and receives the highest number of votes, and that the winning candidate has not been proclaimed or has taken his oath of office. (Domino v Comelec, 310 SCRA 546) D. PETITIONS i. Petition to deny due course or cancel certificate of candidacy(Rule 23, COMELEC Rules of Procedure; Section 78 of BP 881) Section 1. Grounds for Denial of Certificate of Candidacy. A petition to deny due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy for any elective office may be

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

filed with the Law Department of the Commission by any citizen of voting age or a duly registered political party, organization, or coalition or political parties on the exclusive ground that any material representation contained therein as required by law is false. Section 2.Period to File Petition. The petition must be filed within five (5) days following the last day for the filing of certificate of candidacy. Section 3.Summary Proceeding. The petition shall be heard summarily after due notice. It also provided in Rule 24, Section 2 of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure that the Commission may refuse to give due course to or cancel a Certificate of Candidacy of any candidate if the certificate filed is a substitute Certificate of Candidacy, when it is not a proper case of substitution under Sec. 77 of BP 881. There are two instances where a petition questioning the qualifications of a registered candidate to run for the office for which his certificate of candidacy was filed can be raised under the Omnibus Election Code (B.P. Blg. 881), to wit: 1) Before election, pursuant to Section 78 thereof 2) After election, pursuant to Section 253 thereof (petition for quo warranto)

ii.

Petition for Disqualification (Rule 25, COMELEC Rules of Procedure) Section 1. Grounds for Disqualification Any candidate who does not possess all the qualifications of a candidate as provided for by the Constitution or by existing law or who commits any act declared by section 12 and 68 of the BP 881, section 40 of R.A 7160 and under section 4 of R.A 8295 as grounds for disqualification may be disqualified from continuing as a candidate. Section 2. Who may file for Disqualification Any citizen of the Philippines which is of voting age, or duly registered political party, organization or coalition of political parties may file with the Law Department of the COMELEC a petition to disqualify a candidate on grounds provided by law. The petition shall be filed any day after the last day for filing of certificates of candidacy but not later than the date of proclamation which shall be heard summarily after due notice. Section 5.Effect of Petition if Unresolved Before Completion of Canvass. If the petition, for reasons beyond the control of the Commission, cannot be decided before the completion of the canvass, the votes cast for the respondent may be included in the counting and in the canvassing; however, if the evidence of guilt is strong, his proclamation shall be suspended notwithstanding the fact that he received the winning number of votes in such election.

iii.

Distinguish: Petition to Deny Due Course or to Cancel Certificates of Candidacy and Petition for Disqualification

A petition for disqualification is properly filed when a candidate commits any act declared by section 12 and 68 of the BP 881, section 40 of R.A 7160 and under section 4 of R.A 8295 as

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

10

grounds for disqualification. On the other hand, a petition to deny due course or to cancel certificate of candidacy can be grounded on a statement of false material representation in the certificate. While a person who is disqualified under Section 68 is merely prohibited to continue as a candidate, the person whose certificate is cancelled or denied due course under Section 78 is not treated as a candidate at all, as if she never filed a COC. Thus, in the case of Miranda vs. Abaya, 30 Phil. 642 (1999) the SC made the distinction that a candidate who is disqualified under Section 68 van validly be substituted under section 77 of BP 881 because s/he remains a candidate until disqualified; but a person whose COC has been denied due course or cancelled under Section 78 cannot be substituted because s/he is never considered a candidate. E. EFFECTS OF DISQUALIFICATIONS (Section 6, R.A. No. 6646) Section 6.Effect of Disqualification Case. Any candidate who has been declared by final judgment to be disqualified shall not be voted for, and the votes cast for him shall not be counted. If for any reason a candidate is not declared by final judgment before an election to be disqualified and he is voted for and receives the winning number of votes in such election, the Court or Commission shall continue with the trial and hearing of the action, inquiry, or protest and, upon motion of the complainant or any intervenor, may during the pendency thereof order the suspension of the proclamation of such candidate whenever the evidence of his guilt is strong. Section 7. Petition to Deny Due Course To or Cancel a Certificate of Candidacy. The procedure hereinabove provided shall apply to petitions to deny due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy as provided in Section 78 of Batas Pambansa Blg. 881.

Disqualification BEFORE election A candidate disqualified by final judgment before an election CANNOT be voted for, and votes cast for him shall not be counted. The votes garnered by them shall be considered as stray votes as he was never a candidate in the elections. Disqualification AFTER election those candidates who had been disqualified after election, doctrine on the rejection of the second placer shall be applied. Doctrine of Rejection of Second Placer The rule that a candidate who obtains the second highest number of votes may not be proclaimed winner in case the winning candidate is disqualified is now settled. To assume that the second placer would have received the other votes would be to substitute our judgment for the mind of the voter. The second placer is just a second placer. He lost the elections. He was repudiated by either a majority or plurality of voters. The doctrine of rejection of second placer will apply if two conditions concur: 1) The decision on disqualification remained pending on election day; and 2) The decision on disqualification became final only after the elections

CASE 7: DOMINO vs COMELEC (310 SCRA 546)

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

11

FACTS: Petitioner Juan Domino ran for Congressman of Sarangani. He was disqualified on residency requirements. On 11 May 1998, the day of the election, the COMELEC issued Supplemental Omnibus Resolution No. 3046, ordering that the votes cast for DOMINO be counted but to suspend the proclamation if winning, considering that the Resolution disqualifying him as candidate had not yet become final and executory. The candidate who gathered the second highest number of votes intervened in the case and said that she should be declared as a winner since Domino was disqualified from running for the position. ISSUE: Whether or not the doctrine on the rejection of the second placer should be applied. HELD: It is now settled doctrine that the candidate who obtains the second highest number of votes may not be proclaimed winner in case the winning candidate is disqualified. In every election, the peoples choice is the paramount consideration and their expressed will must, at all times, be given effect. When the majority speaks and elects into office a candidate by giving the highest number of votes cast in the election for that office, no one can be declared elected in his place. It would be extremely repugnant to the basic concept of the constitutionally guaranteed right to suffrage if a candidate who has not acquired the majority or plurality of votes is proclaimed a winner and imposed as the representative of a constituency, the majority of which have positively declared through their ballots that they do not choose him.

CASE 8: CAYAT V. COMELEC G.R. No. 163776 April 24, 2007 FACTS: Cayat and Palileng are the only mayoralty candidates for the May 2004 elections in Buguias Benguet. Palileng filed a petition for cancellation of the COC of Cayat on the ground of misrepresentation. Despite this decision, Cayat was still proclaimed as the winner and Palileng filed a petition for annulment of proclamation. COMELEC then declared Palileng as the duly elected mayor and Feliseo Bayacsan as the duly elected vice mayor. Bayacsan argues that he should be declared as mayor because of the doctrine of rejection of second placer. ISSUE: WON the rejection of second placer doctrine is applicable. HELD: The doctrine cannot be applied in this case because the disqualification of Cayat became final and executor before the elections and hence, there is only one candidate to speak of. The law expressly declares that a candidate disqualified by final judgment before an election

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

12

cannot be voted for, and votes cast for him shall not be counted. As such, Palileng is the only candidate and the duly elected mayor. The doctrine will apply in Bayacsans favor, regardless of his intervention in the present case, if two conditions concur: (1) the decision on Cayats disqualification remained pending on election day, 10 May2004, resulting in the presence of two mayoralty candidates for Buguias, Benguet in the elections; and (2)the decision on Cayats disqualification became final only after the elections.

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

13

FILING OF CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDACY A. Certificate of candidacy (Sec 73, BP 881) No person shall be eligible for any elective public office unless he files a sworn certificate of candidacy within the period fixed herein. B. Candidate Defined (Sec 6, BP 881) Any person aspiring for or seeking an elective public office, who has filed a certificate of candidacy by himself or through an accredited political party, aggroupment, or coalition of parties. C. Mode of Filing (Sec 3, COMELEC RESOLUTION NO. 9518) XXX. The Certificate of Candidacy shall be filed by the candidate personally or by his duly authorized representative, whose authority shall be in writing, under oath and attached thereto. No Certificate of Candidacy shall be filed or accepted by mail, electronic mail, telegram or facsimile. XXX D. Time of Filing (Sec 13, RA 9396) The Commission shall set the deadline for the filing of certificate of candidacy/petition of registration/manifestation to participate in the election. Any person who files his certificate of candidacy within this period shall only be considered as a candidate at the start of the campaign period for which he filed his certificate of candidacy. E. Place of Filing (Sec 3, COMELEC RESOLUTION NO. 9518) The certificate of candidacy shall be filed in FIVE (5) LEGIBLE COPIES with the offices of the Commission specified hereunder: Law Department, Commission on Elections: For President, Vice-President and Senator. Regional Election Director, NCR: For Members of the House of Representatives for legislative districts in the National Capital Region (NCR); Provincial Election Supervisor concerned: o Members of the House of Representatives of legislative districts in provinces; o For Provincial officials; City Election Officer concerned designated for the purpose by the Regional Election Director. o Members of the House of Representatives for legislative districts in cities outside the NCR, which comprise one or more legislative districts; o For City Officials of cities with more than one election officer. Copies of the designation of the Election Officer concerned shall immediately be submitted to the Law Department of the Commission; City/Municipal Election Officer concerned: For City/Municipal Officials

Certificate of candidacy not filed with the correct offices as enumerated above shall not be accepted. F. Prohibition Against Filing of Multiple Candidacies (Sec 73, BP 881)

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

14

No person shall be eligible for more than one office to be filled in the same election, and if he files his certificate of candidacy for more than one office, he shall not be eligible for any of them. XXX G. Contents of Certificate of Candidacy (Sec. 74, BP 811) The certificate of candidacy shall state that the person filing it is announcing his candidacy for the office stated therein and that he is eligible for said office; if for Member of the Batasang Pambansa, the province, including its component cities, highly urbanized city or district or sector which he seeks to represent; the political party to which he belongs; civil status; his date of birth; residence; his post office address for all election purposes; his profession or occupation; that he will support and defend the Constitution of the Philippines and will maintain true faith and allegiance thereto; that he will obey the laws, legal orders, and decrees promulgated by the duly constituted authorities; that he is not a permanent resident or immigrant to a foreign country; that the obligation imposed by his oath is assumed voluntarily, without mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that the facts stated in the certificate of candidacy are true to the best of his knowledge. Unless a candidate has officially changed his name through a court approved proceeding, a certificate shall use in a certificate of candidacy the name by which he has been baptized, or if has not been baptized in any church or religion, the name registered in the office of the local civil registrar or any other name allowed under the provisions of existing law or, in the case of a Muslim, his Hadji name after performing the prescribed religious pilgrimage: Provided, That when there are two or more candidates for an office with the same name and surname, each candidate, upon being made aware or such fact, shall state his paternal and maternal surname, except the incumbent who may continue to use the name and surname stated in his certificate of candidacy when he was elected. He may also include one nickname or stage name by which he is generally or popularly known in the locality. The person filing a certificate of candidacy shall also affix his latest photograph, passport size; a statement in duplicate containing his bio-data and program of government not exceeding one hundred words, if he so desires. Mandatory Before Election but Directory Afterwards CASE 9: SINACA vs MULA and COMELEC 315 SCRA 266 The provision of the election law regarding certificates of candidacy, such as signing and swearing, and the information required to be stated therein, are considered mandatory prior to the elections. Thereafter, they are regarded as merely directory. The proclamation of the candidate as winner may not be nullified on such ground. The defects in the certificates should have been questioned before the election; they may not be questioned after the election without invalidating the will of the electorate, which should not be done. The Supreme Court laid down its exception to the aforementioned rule. It ruled that if the contents of the COC have defects beyond matters of form and material misrepresentations then the candidate cannot avail of the benefit of our ruling that COC mandatory requirements before elections are considered merely directory after the people shall have spoken. A mandatory and material election law requirement involves more than the will of the people in any given locality. Where a material COC misrepresentation under oath is

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

15

made, thereby violating both our election and criminal laws, we are faced as well with an assault on the will of the people of the Philippines as expressed in our laws. In a choice between provisions on material qualifications of elected officials, on the one hand, and the will of the electorate in any given locality, on the other, we believe and so hold that we cannot choose the electorate will. The balance must always tilt in favor of upholding and enforcing the law. To rule otherwise is to slowly gnaw at the rule of law. H. Correction of Certificate A certificate of candidacy may be corrected. Once entries in a certificate of candidacy are corrected, it is the corrected version which is considered filed and not the earlier one. (Yason v. Comelec, 134 SCRA 371 (1985) The amendment of the certificate, although made after the deadline for filing it, but before the election, is a substantial compliance with the law and cures its defect. (Alialy v. Comelec, 2 SCRA 957 (1961)

I.

Effect of Filing Sec 66 of OEC Candidates Holding Appointive Office or Position- Any person holding a public office or position, including active members of AFP and officers and employees in GOCC, shall be considered ipso facto resigned from his office upon filing of his certificate of candidacy.

Sec 67 of OEC Candidates holding elective office - Any elective official, whether national or local running for any office other than the one which he is holding in permanent capacity, except for President and Vice President, shall be considered ipso facto resigned from his office upon filling of hi certificate of candidacy.

RA 9006 Sec 14 repealed Sec 67 but maintained Sec. 66 of the Omnibus Election Code so that now, only appointive officials running for elective office are deemed resigned upon filing of certificate of candidacy. In addition to that Sec. 6.6, R.A. 9006 or Fair Election Act states that: Any mass media columnist, commentator, announcer, reporter, on-air correspondent or personality who is a candidate for any elective public office shall be deemed resigned, if so required by his/her employer, or shall take a leave of absence from his/her work as such during the campaign period. J. Nuisance Candidate (Sec. 69, BP 881) The Commission may, motu proprio or upon a verified petition of an interested party, refuse to give due course to or cancel a certificate of candidacy if it is shown that said certificate has been filed by a nuisance candidate. A nuisance candidate is one who files a certificate of candidacy:

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

16

(a) To put the election process in mockery or disrepute; or (b) To cause confusion among the voters by the similarity of the names of the registered candidates, or (c) Clearly demonstrating that he/she has no bona fide intention to run for the office which the certificate of candidacy has been filed, and thus prevents a faithful determination of the true will of the electorate. i. Nature of Proceedings

Proceedings to have a candidate declared as a nuisance candidate are summary in nature. In lieu of oral testimonies, the parties may be required to submit position papers together with affidavits or counter-affidavits and other documentary evidence. ii. 1. 2. Who May File Disqualification Case Against Nuisance Candidate

Motu propio by the Comelec Verified petition by any registered candidate iii. Period of Filing

The petition shall be filed personally or through an authorized representative, within five (5) days from the last day for the filing of certificates of candidacy. (Sec. 3, Rule 24 COMELEC Rules of Procedure) iv. (1) Procedure (Sec. 5, R.A No. 6646)

The petition is filed with the COMELEC personally or through duly-authorized representative within 5 days from the last day for the filing of certificates of candidacy. Filing by mail is not allowed. Within 3 days from the filing of the petition, the COMELEC shall issue summons to the respondent candidate, together with a copy of the petition and its enclosures, if any. The respondent shall then have 3 days from receipt of the summons to file his verified answer (not a motion to dismiss) to the petition, serving copy thereof upon the petitioner. Grounds for a motion to dismiss may be raised as an affirmative defense. The COMELEC may then designate any of its officials who are lawyers to hear the case and receive evidence. In lieu of oral testimonies, the parties may be required to submit position papers together with affidavits or counter-affidavits and other documentary evidence. The hearing officer shall immediately submit to the COMELEC his findings, reports, and recommendations within 5 days from the completion of such submission of evidence. The COMELEC shall then render its decision within 5 days from receipt of the findings of the hearing officer. This decision shall be disseminated by the COMELEC to the city or municipal election registrars, boards of election inspectors, and the general public in the political subdivision concerned within 24 hours through the fastest available means.

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

17

(6)

After 5 days from receipt of the parties, the decision becomes final and executory unless stayed by the Supreme Court.

Case 10: PAMATONG vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 161872, April 13, 2004 Equal access to opportunity for public service is a privilege subject to limitations Rev. Elly Velez Pamatong ran for president. COMELEC denied due course on ground that he is a nuisance candidate: he cannot wage a nationwide campaign and/or not nominated by a political party or not supported by a registered by a political party with a national constituency. Pamatong contended that his right to equal access to opportunity for public service was violated. Supreme Court held that equal access to opportunity for public service is not a constitutional right but a privilege subject to limitations imposed by law. Sec. 26, Art. II neither bestows such a right nor elevates the privilege to an enforceable right. The aforesaid provision forms part of the Declaration of Principles of State Policies, which is generally considered non- self-executing and are merely guidelines for legislative or executive action, and not operative because in the absence of legislation, it lacks proper definition of its effective means and reach. As long as limitations are applied equally without discrimination, the equal access clause is not violated. The rationale is that the State has a compelling interest to ensure that its electoral exercises are rational, objective and orderly. The poll would be bogged by irrelevant minute covering every step of the electoral process, most probably posed at the instance of these nuisance candidates. Owing to the superior interest in ensuring a credible and orderly election, the State could exclude nuisance candidates and need not indulge in their trips to the moon on gossamer wings. K. Guest Candidates (Sec 70, BP 881) A political Party may nominate and/or support candidates not belonging to it. L. Withdrawal of Certificate of Candidacy Sec 73, BP 881 - Xxx A person who has filed a certificate of candidacy may, prior to the election, withdraw the same by submitting to the office concerned a written declaration under oath. No person shall be eligible for more than one office to be filled in the same election, and if he files his certificate of candidacy for more than one office, he shall not be eligible for any of them. However, before the expiration of the period for the filing of certificates of candidacy, the person who has filed more than one certificate of candidacy may declare under oath the office for which he desires to be eligible and cancel the certificate of candidacy for the other office or offices." Sec 14, COMELEC RES. NO. 9518 - Any person who has filed a Certificate of Candidacy may, at any time before election day and subject to Sec. 15 hereof, file personally a Statement of Withdrawal under oath, in five (5) legible copies, with the office where the Certificate of Candidacy was filed. No Statement of Withdrawal shall be accepted if filed

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

18

by a person other than the candidate himself or if filed by mail, electronic mail, telegram or facsimile. xxx Xxx The filing of a withdrawal of a Certificate of Candidacy shall not affect whatever civil, criminal or administrative liabilities a candidate may have incurred. A person who has withdrawn his Certificate of Candidacy for a position shall not be eligible, whether as a substitute candidate or not, for any other position. Case 11: GO vs COMELEC GR. No. 147741 (2001) Petitioner filed with the municipal election officer of the municipality of Baybay, Leyte, a certificate of candidacy for mayor of Baybay, Leyte on February 27, 2001. However, on February 28, 2001 she filed another certificate of candidacy for the position of Governor, because of this she sought the withdrawal of her COC as mayor. However, the provincial election supervisor of Leyte refused to accept the affidavit of withdrawal and suggested that, pursuant to a COMELEC resolution, she should file it with the municipal election officer of Baybay, Leyte where she filed her certificate of candidacy for mayor. Only a few minutes were left before the deadline so instead of going to Baybay Leyte to personally seek the cancellation she decided to just fax her withdrawal to her father living in Balay. The father was able to send it at 12:28 am, the following day. The respondent Montejo and several other sought the disqualification of petitioner because she filed two COCs. COMELEC gave due course to the petition of Montejo. Hence this petition. The issues to be resolved are as follows: Is petitioner disqualified to be candidate for governor of Leyte and mayor of Baybay, Leyte because she filed certificates of candidacy for both positions? Was there a valid withdrawal of the certificate of candidacy for municipal mayor of Baybay, Leyte? (a) Must the affidavit of withdrawal be filed with the election officer of the place where the certificate of candidacy was filed? (b) May the affidavit of withdrawal be validly filed by fax? Petition was granted, annulling the COMELEC resolution declaring petitioner disqualified for both positions of governor of Leyte and mayor of the municipality of Baybay, Leyte. The filing of the affidavit of withdrawal with the election officer of Baybay, Leyte, at 12:28 a.m., 1 March 2001 was a substantial compliance with the requirement of the law. The court holds that petitioner's withdrawal of her certificate of candidacy for mayor of Baybay, Leyte was effective for all legal purposes, and left in full force her certificate of candidacy for governor. There is nothing in Sec 72 o BP 188 which mandates that the affidavit of withdrawal must be filed with the same office where the certificate of candidacy to be withdrawn was filed. Thus, it can be filed directly with the main office of the COMELEC, the office of the regional election director concerned, the office of the provincial election supervisor of the province to which the municipality involved belongs, or the office of the municipal election officer of the said municipality.

M.

Substitution of Candidates

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

19

Sec. 77, BP 881 - Candidates in case of death, disqualification or withdrawal of another If after the last day for the filing of certificate of candidacy, an official candidate of a registered or accredited political party dies, withdraws or is disqualified for any cause, only a person belonging to, and certified by, the same political party may file a certificate of candidacy to replace the candidate who died, withdrew or was disqualified. xxx SEC. 15 COMELEC Resolution No. 9581. Substitution of Candidates in case of death, disqualification or withdrawal of another. - If after the last day for the filing of Certificates of Candidacy, an official candidate of a duly registered political party or coalition of political parties dies, withdraws or is disqualified for any cause, he may be substituted by a candidate belonging to, and nominated by, the same political party. No substitute shall be allowed for any independent candidate. The substitute of a candidate who has withdrawn on or before December 21, 2012 may file his Certificate of Candidacy for the office affected not later than December 21, 2012, so that the name of the substitute will be reflected on the official ballots. No substitution due to withdrawal shall be allowed after December 21, 2012. The substitute for a candidate who died or is disqualified by final judgment, may file his Certificate of Candidacy up to mid-day of election day, provided that the substitute and the substituted have the same surnames. If the death or disqualification should occur between the day before the election and mid-day of election day, the substitute candidate may file his Certificate of Candidacy with any Board of Election Inspectors in the political subdivision where he is a candidate, or in the case of a candidate for Senator, with the Law Department of the Commission on Elections in Manila, provided that the substitute and the substituted candidate have the same surnames.

Can independent candidates be substituted in any of the instances mentioned above? While the law specifically mentions that candidates who are party members may be substituted, the law nevertheless does not expressly prohibit the substitution of independent candidates. The law being silent on the matter, this cannot be perceived as a prohibition.

Substitution not allowed when certificate was denied due course. A person without a valid certificate of candidacy cannot be considered as a candidate, much the same as one who has no certificate of candidacy.

CASE 12: ONG vs. ALEGRE, G.R. No. 163295, Jan. 23, 2006 Ong (incumbent) and Alegre are both running for mayor. Ongs certificate of candidacy was denied due course on ground of violation of three-term rule. Thus, he was substituted by

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

20

Romeo Ong. Was the substitution valid? The Supreme Court held that while there is no dispute as to whether or not a nominee of a registered or accredited political party may substitute for a candidate of the same party who had been disqualified for any cause, this does not include those cases where the certificate of candidacy of the person to be substituted had been denied due course and cancelled under sec. 78 of the Code. Expression unius est exclusio alterius. While the law enumerated the occasions where a candidate may be validly substituted, there is no mention of the case where a candidate is excluded not only by disqualification but also by denial and cancellation of his certificate of candidacy. Under the foregoing rule, there can be no valid substitution for the latter case, much in the same way that a nuisance candidate whose certificate of candidacy is denied due course and/or cancelled may not be substituted. If the intent of the lawmakers were otherwise, they could have so easily and conveniently included those persons whose certificates of candidacy have been denied due course and/or cancelled under the provisions of sec. 78 of the Code.

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

21

POLITICAL PARTIES A. DEFINITION "Political party" or "party", when used in this Act, means an organized group of persons pursuing the same ideology, political ideas or platforms of government and includes its branches and divisions. To acquire juridical personality, quality it for subsequent accreditation, and to entitle it to the rights and privileges herein granted to political parties, a political party shall first be duly registered with the Commission. Any registered political party that, singly or in coalition with others, fails to obtain at least ten percent of the votes cast in the constituency in which it nominated and supported a candidate or candidates in the election next following its registration shall, after notice and hearing be deemed to have forfeited such status as a registered political party in such constituency. (Section 60, Omnibus Election Code) A political party is an organized group of persons pursuing same political ideals in a government. In order that a group of persons be organized, all of them must be joined in a corporate body, articulate, with attributes of a social personality. In addition, it must have a constitution, by-laws, rules or some kind of charter. Some kind of agreement, written or not must exist on how the group is to function, how it will be presided over, and how it is to express its collective will. B. REGISTRATION Section 61 of the Omnibus Election code provides that: Any organized group of persons seeking registration as a national or regional political party may file with the Commission a verified petition attaching thereto its constitution and by-laws, platform or program of government and such other relevant information as may be required by the Commission. The Commission shall, after due notice and hearing, resolve the petition within ten days from the date it is submitted for decision. No religious sect shall be registered as a political party and no political party which seeks to achieve its goal through violence shall be entitled to accreditation. The listing of political parties is for registration and accreditation. Registration is the means by which the government is enabled to supervise and regulate the activities of various elements participating in an election. Accreditation is the means by which the registration requirement is made effective by conferring benefits to registered political parties. (Peralta vs COMELEC, 82 SCRA 30) i. Purpose

The purpose of registration of political parties with the COMELEC is to enable them to: (1) Acquire juridical personality; (2) Qualify for subsequent accreditation; and (3) Entitle them to the rights and privileges granted to political parties.

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

22

The purpose of the law recognizing the legal personality of political aggroupments for election purposes is to foster and encourage the formation of political parties, inspired by high political ideas in government. (Sumulong vs COMELEC, 70 Phil 703) ii. (1) Procedure for Registration (Rule 32, COMELEC Rules of Procedure) The political party seeking registration may file with the COMELEC a verified petition attaching thereto its constitution and by-laws, platform or program of government and such other relevant information as may be required by the COMELEC. Upon receipt of the reports from its field offices, the Commission shall immediately set the petition for hearing and shall send notices to the petitioner and other parties concerned. On the day following the receipt of the notice of hearing, the petitioner shall cause the publication of the petition, together with the notice of hearing, in three (3) daily newspaper of general circulation, notifying in writing the Commission of such action.

(2)

(3)

C.

WHO MAY NOT BE REGISTERED 1. 2. 3. 4. Religious sects Those which seeks to achieve their goals through unlawful means Those which refuse to adhere to the Constitution Those that are supported by any foreign government

F.

GROUNDS FOR CANCELLATION OF REGISTRATION (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Accepting financial contributions from foreign governments or their agencies (Art. IX-C, Sec. 2 (5), 1987 Constitution); The party is a religious sect or denomination, organization or association organized for religious purposes (Sec. 6 (1), R.A. 7941); The party advocates violence or unlawful means to seek its goal (Sec. 6 (2), R.A. 7941); The party is a foreign party or organization (Sec. 6 (3), R.A. 7941); The party is receiving support from any foreign government, foreign political party, foundation, organization, whether directly or through any of its officers or members or indirectly through third parties for partisan election purposes (Sec. 6 (4), R.A. 7941); The party violates or fails to comply with laws, rules or regulations relating to elections (Sec. 6 (5), R. A. 7941); The party declares untruthful statements in its petition for registration (Sec. 6 (6), R.A. 7941); The party has ceased to exist for at least 1 year (Sec. 6 (7), R.A. 7941); The party fails to participate in the last 2 preceding elections (Sec. 6 (8), R.A. 7941); If registered under the party-list system, the party fails to obtain at least 2% of the votes in the 2 preceding elections for the constituency in which it has registered. (Sec. 6 (8), R.A. 7941)

(6) (7) (8) (9) (10)

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

23

Under the party-list system, the COMELEC may refuse or cancel registration either motu propio or upon verified complaint of any interested party, after due notice and hearing. (Sec. 6, R.A. 7941)

GROUP 3 :: PALLE :: PUYALES ::

24

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Torts 8Document7 pagesTorts 8Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of WitnessDocument2 pagesAffidavit of WitnessMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambigous 2Document2 pagesAmbigous 2Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

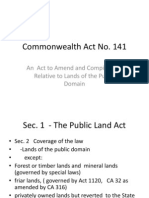

- Commonwealth Act NoDocument86 pagesCommonwealth Act NoMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- People's Small-Scale Mining Act of 1991 RA 7076 Sec. 2 Declaration of PolicyDocument38 pagesPeople's Small-Scale Mining Act of 1991 RA 7076 Sec. 2 Declaration of PolicyMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Post-Arrest Procedure and ExceptionsDocument6 pagesPost-Arrest Procedure and ExceptionsMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Adoption CasesDocument4 pagesAdoption CasesMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Gotesco Properties, Inc. vs. Spouses Edna and Alberto Moral G.R. NO. 176834 November 21, 2012 FactsDocument2 pagesGotesco Properties, Inc. vs. Spouses Edna and Alberto Moral G.R. NO. 176834 November 21, 2012 FactsMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Habeas Corpus CasesDocument6 pagesHabeas Corpus CasesMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- 11111111Document2 pages11111111Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Capalla vs. ComelecccDocument14 pagesCapalla vs. ComelecccMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Procedure For Environmental CasesDocument90 pagesProcedure For Environmental CasesMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Jan 11Document36 pagesJan 11Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- La Bugal-B'Laan v. RamosDocument49 pagesLa Bugal-B'Laan v. RamosMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Clear Air Act of 1999Document6 pagesPhilippine Clear Air Act of 1999Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection ActDocument49 pagesWildlife Resources Conservation and Protection ActMonefah Mulok50% (2)

- Public Corporations: General PrinciplesDocument23 pagesPublic Corporations: General PrinciplesMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- WillsDocument5 pagesWillsMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- MonDocument15 pagesMonMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- EvvvidDocument3 pagesEvvvidMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Gotesco Properties, Inc. vs. Spouses Edna and Alberto Moral G.R. NO. 176834 November 21, 2012 FactsDocument2 pagesGotesco Properties, Inc. vs. Spouses Edna and Alberto Moral G.R. NO. 176834 November 21, 2012 FactsMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Salesss AssortedDocument19 pagesSalesss AssortedMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Jan 11Document36 pagesJan 11Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. NO. 32432 SEPTEMBER 11, 1970 Imbong vs. ComelecDocument31 pagesG.R. NO. 32432 SEPTEMBER 11, 1970 Imbong vs. ComelecMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- January 7Document7 pagesJanuary 7Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- ENVI Provisions LGC (Revised)Document11 pagesENVI Provisions LGC (Revised)Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambigous 2Document2 pagesAmbigous 2Monefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 172954 October 5, 2011 ENGR. JOSE E. CAYANAN, Petitioner, North Star International Travel, Inc., RespondentDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 172954 October 5, 2011 ENGR. JOSE E. CAYANAN, Petitioner, North Star International Travel, Inc., RespondentMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Public Corporations: General PrinciplesDocument23 pagesPublic Corporations: General PrinciplesMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- Salesss AssortedDocument19 pagesSalesss AssortedMonefah MulokPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Civ Civils Notes 2019Document123 pagesCiv Civils Notes 2019DPas encore d'évaluation

- MINORITIES SEATS For Upload LatestDocument6 pagesMINORITIES SEATS For Upload LatestSikandar ZahoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court upholds citizenship of property ownerDocument8 pagesSupreme Court upholds citizenship of property ownerRomana AfrozePas encore d'évaluation

- Family Project Final PDFDocument15 pagesFamily Project Final PDFKartik BhargavaPas encore d'évaluation

- B. Sc. LL. B. Conflict of Laws AssignmentDocument2 pagesB. Sc. LL. B. Conflict of Laws AssignmentArchit Virendra SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Registration Form - Uttarakhand Suboardinate Service Selection CommissionDocument4 pagesReview Registration Form - Uttarakhand Suboardinate Service Selection CommissionRohit SaxenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Admin Law - Digests For Powers & Duties of Public OfficersDocument2 pagesAdmin Law - Digests For Powers & Duties of Public OfficersElixirLanganlanganPas encore d'évaluation

- Conflict of Laws Reviewer 1Document56 pagesConflict of Laws Reviewer 1Abigael Severino100% (3)

- Ujano Vs RepublicDocument2 pagesUjano Vs RepublicElyn ApiadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sottomayor Vs de BarrosDocument1 pageSottomayor Vs de Barrosmelaniem_1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Agot, HR-Law Assignment 3Document11 pagesAgot, HR-Law Assignment 3Crystal KatePas encore d'évaluation

- Theories of Private International LawDocument20 pagesTheories of Private International LawAadityaVasu71% (35)

- Election Qualification RequirementsDocument2 pagesElection Qualification RequirementsNathalie Faye Abad ViloriaPas encore d'évaluation

- OutlineDocument72 pagesOutlineMichael MarksPas encore d'évaluation

- Legitimacy and Legitimation Conflict of LawsDocument21 pagesLegitimacy and Legitimation Conflict of LawsAyush Bansal100% (2)

- Succession under Indian Succession Act for ChristiansDocument16 pagesSuccession under Indian Succession Act for ChristiansPRANOY GOSWAMIPas encore d'évaluation

- Validity of MarriageDocument17 pagesValidity of MarriageRicha RajpalPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.penera Vs COMELECDocument57 pages1.penera Vs COMELECJoseph Lorenz AsuncionPas encore d'évaluation

- First National Bank Vs RostekDocument10 pagesFirst National Bank Vs RostekMjay GuintoPas encore d'évaluation

- Estate dispute over HK property rightsDocument15 pagesEstate dispute over HK property rightsJYhkPas encore d'évaluation

- General Terms and Conditions of Business of Cleverbridge AGDocument8 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of Business of Cleverbridge AGRashid SaidPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Family LawDocument31 pagesIntroduction To Family LawcarolynPas encore d'évaluation

- Who Is MinorDocument6 pagesWho Is Minorabhijeet sinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Teodulo M. Coquilla Vs The Hon. Commission On Elections and Mr. Neil M. AlvarezDocument3 pagesTeodulo M. Coquilla Vs The Hon. Commission On Elections and Mr. Neil M. AlvarezCRSS Region VII100% (1)

- Asistio v. AguirreDocument8 pagesAsistio v. AguirreHaniyyah FtmPas encore d'évaluation

- Marcos v. Comelec (G.r. No.119976)Document2 pagesMarcos v. Comelec (G.r. No.119976)Roward100% (5)

- Citizenship Act 1955 modes of acquiring Indian citizenshipDocument6 pagesCitizenship Act 1955 modes of acquiring Indian citizenshipManas DasPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Library Inheritance Tax Case SummaryDocument7 pagesE-Library Inheritance Tax Case SummaryKennethQueRaymundoPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature: Generally Special Proceedings Are NonDocument10 pagesNature: Generally Special Proceedings Are NonRaymond MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- San Luis v. San LuisDocument12 pagesSan Luis v. San LuiscyhaaangelaaaPas encore d'évaluation