Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

International Business

Transféré par

Siddharth ReddyDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

International Business

Transféré par

Siddharth ReddyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of International Business Studies (2009) 40, 255273

& 2009 Academy of International Business All rights reserved 0047-2506

www.jibs.net

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

College of Business, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA Correspondence: G Knight, Florida State University, College of Business, PO Box 3061110, Tallahassee, FL 32306-1110, USA Tel: 1 850 644 1140; Fax: 1 850 644 4098; E-mail: gknight@fsu.edu

Abstract The trend of increasing internationalization of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is noteworthy, because such firms typically have far fewer financial and tangible resources than large multinational enterprises. As a result, international business is often more challenging for smaller firms. In this study we investigate the widespread internationalization of SMEs, and specific factors that support their superior performance abroad. We uncover a collection of intangible capabilities that are especially salient to these firms and their growing international involvement. We identify international business competence (IBC) as an intangible, overarching firm resource that engenders superior international performance in the international SME. Through case studies and a comprehensive literature review, we identify four dimensions of IBC. We devise and assess a model that links IBC to SME international performance. Results suggest that international orientation, international marketing skills, international innovativeness, and international market orientation are all significant dimensions of IBC, and that IBC is instrumental in SME international performance. We discuss resultant findings and offer managerial implications. Journal of International Business Studies (2009) 40, 255273. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400397

Keywords: capabilities view; resource-based view; international business competence; international performance; small and medium enterprise

Received: 13 October 2005 Revised: 19 December 2006 Accepted: 10 September 2007 Online publication date: 29 May 2008

INTRODUCTION International business has been dominated by large, multinational enterprises (MNEs). However, globalization, combined with advancing information and communications technologies (ICT), is contributing to a growing role in international business for the small and medium enterprise (SME; defined as firms with 500 or fewer employees) (Coviello & McAuley, 1999; Knight, 2000). Since the 1980s the number of internationally active SMEs has increased dramatically. It is estimated that over one million SMEs, or as many as 30% of the manufacturing SMEs in the industrialized countries, are now active in international business, accounting for more than a third of world merchandise trade (OECD, 1997). These businesses are expanding into multiple foreign markets, and draw upwards of 60% of total revenue from abroad (e.g., Chuushoo Kigyoo Cho, 1995; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; OECD, 1997). Recognition of the increasing role of international SMEs is exemplified by the work of Oviatt and McDougall (1994), whose seminal work on international new ventures received the JIBS Decade Award in 2004. However, globalization, ICT, and other external trends by themselves are insufficient to explain the intriguing processes at

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

256

work in the successful international SME. International SMEs tend not to fit the profile of traditional multinational firms those with substantial financial and tangible resources. SMEs tend to possess far fewer of the tangible assets, such as plant, property, and equipment, as well as financial and human resources, that usually favor the internationalization of large MNEs. As a result, the complexities of international operations are more challenging for SMEs (Craig & Douglas, 1996; Czinkota, 1982). For such firms internationalization is an innovative act, and suggests the existence of processes that distinguish them from better-resourced, larger firms (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). But, despite the growing salience of international SMEs, there has been little research to investigate the intangible resources that these firms employ in order to expand abroad. That is, our understanding of how SMEs nurture and structure intangible resources to overcome limited tangible resources to achieve international business success is still limited. For instance, although researchers have explored the role of some firm characteristics, such as international market orientation (Cadogan, Diamantopoulos, & de Mortanges, 1999; Cadogan, Diamantopoulos, & Siguaw, 2002; Racela, Chaikittisilpa, & Thoumrungroje, 2007), international marketing mix (Atuahene-Gima, 1995; Cavusgil & Zou, 1994), and even managerial attitudes (Brady & Bearden, 1979) in export performance, research on the role of these and other intangible resources, and their interrelationships with and linkage to the emergent international SME, is only just beginning to emerge. This study attempts to make several contributions by exploring this gap in the literature. First, we examine the role of specific organizational competences, intangible resources that engender success in the international SME. In the literature, business competences and innovation have been central research themes regarding organizational strategy and performance (e.g., Dev, Erramilli, & Agarwal, 2002; Hurley & Hult, 1998; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). By contrast, there has been very little empirical research aimed at uncovering the bundles of firm competences that characterize the innovative processes that underlie recent international success among countless SMEs. Current knowledge in this area is fragmented and incomplete, and the benefit of SMEs being competent in international business, or what it takes to achieve this competence, is not yet clear. In extending our understanding in this area,

we conceptualize a new construct, international business competence (IBC), which incorporates key firm characteristics or factors expected to collectively enhance international performance. The role of IBC in international SME performance is investigated via a series of case studies, with the objective of identifying those specific firm factors that reflect IBC in the international SME. Second, based on these findings, we develop and empirically test a model with several factors that collectively contribute to superior international performance in contemporary SMEs. By linking these factors, in a cohesive manner, to international performance, this study extends the international business literature. Finally, by focusing on international SMEs, we hope to extend knowledge about a category of firm that deserves more research attention. In the following section, we provide the rationale for the emergence of contemporary SMEs and for their international success today. We then summarize relevant literature and conceptualize the concept of international business competence within a proposed theoretical model. We develop a set of hypotheses intended to assess the validity of the proposed model. We next explain our research methods and test the hypotheses in a survey-based study. Finally, we report on empirical findings, providing discussion and conclusions.

THE RESOURCE-BASED VIEW, CAPABILITIES, AND THE INTERNATIONAL SME The ability of SMEs to succeed in foreign markets is largely a function of the internal capabilities and competences of the firm (e.g., Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Wu, Sinkovics, Cavusgil, & Roath, 2007; Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000). Evolutionary economics (Nelson & Winter, 1982) elaborates on the superior ability of firms to develop particular organizational capabilities, consisting of critical competences. The evolutionary economics view highlights the importance of internal capabilities in particular. According to this view, the superior ability of certain firms to create new knowledge leads to the development of organizational capabilities (Wu et al., 2007), consisting of critical competences and embedded routines. Internally, firms prepare for international ventures by developing an appropriate set of competences. Successful international SMEs eschew strictly domestic orientations, and instead adopt a global mindset wherein management views the

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

257

world as the firms marketplace, implanting a culture of international business (e.g., Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida, 2000; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). Fundamental changes in business philosophy and orientation are required to succeed in an international, as opposed to a domestic, marketplace. Given differences between SMEs and large firms, especially regarding the level of tangible resources, we argue that the pattern of business competences internal to the contemporary SME is likely to be distinctive and specific for achieving international success. The resource-based view (RBV) (e.g., Grant, 1996; Penrose, 1959; Teece & Pisano, 1994; Wernerfelt, 1984) helps explain how knowledge and resultant organizational competences, and thus capabilities, are developed and leveraged within enterprising firms. Wernerfelt (1984: 172) defined resources as those (tangible and intangible) assets which are tied semipermanently to the firm. Resources that support firm performance include such assets as inhouse knowledge, employment of skilled personnel, superior strategies, and efficient procedures (Hunt, 2000; Wernerfelt, 1984). We argue that smaller international firms may manifest specific resources comprising orientations and competences that are instrumental to the conception and implementation of activities in international markets. Although these businesses tend to lack substantial financial and human resources, they may leverage a collection of more fundamental, intangible resources that facilitate their international success. The resources consist largely of the know-how, skills, and overall business competences that reside in the managers who work at these firms. Peng (2001) suggests that the RBV can make a significant contribution to international business through its identification of specific knowledge and competences as valuable, unique, and hard-toimitate resources that separate winners from losers in global competition (Dev et al., 2002), allowing smaller firms to differentiate themselves and succeed abroad. Intangible resources that are relatively unique confer competitive advantages by enabling the firm to produce value-added offerings for given markets. When skillfully leveraged, they engender organizational efficiency and/or effectiveness. Accordingly, intangible resources such as international orientation and marketing competence can be instrumental to desired corporate outcomes. Collis (1991) views capabilities as being embedded in the firms culture and routines, and to the extent that they

result in the development of a core competence the vector of assets along which the firm is uniquely advantaged they can provide substantial competitive advantages. Company-level comparative advantages in resources result in marketplace positions of competitive advantage and superior financial performance (Hunt, 2000). In order to achieve competitive advantages, it is also necessary that firm resources be relatively scarce or distinctive (Barney, 1991; Collis, 1991; Mahoney, 1995). Scarcity can be achieved in several ways. For instance, Mahoney (1995) has argued that the degree of the management teams substitutability is a possible source of organizational resource advantage. The management team may be relatively unique regarding the nature and extent of specialized knowledge held by individual managers or embedded within the firm. That is, management at potential rival firms typically lacks the knowledge of the particular circumstances, social structure, and causal relationships of other firms within which actions need to be interpreted (Mahoney, 1995). Causal ambiguity and social complexity give rise to the development of firmspecific knowledge and competences that are imperfectly imitable by would-be rival firms (Barney, 1991). Competitors might well be able to imitate the visible, tangible resources owned by the smaller firm (e.g., plant, equipment, raw materials), but it is more difficult to imitate idiosyncratic knowledge-intensive processes that give rise to superior IBCs and routines (Dev et al., 2002). Competitive imitation of such resources is possible only via the same time-consuming process of irreversible investment or knowledge acquisition that the firm itself underwent (Collis, 1991). It is also possible that resources in international SMEs are no better than those of other firms; rather, core competences arise through superior resource usage (Penrose, 1959). For example, the firm may make better use of human resources through judicious assignment of employees to organizational tasks that results in higher productivity (Dev et al., 2002), or the SME may make better allocations of financial resources toward higher-yield uses (Mahoney, 1995; Williamson, 1985). While firm-specific knowledge and competences play a crucial role in firm performance (Barney, 1991; Dev et al., 2002; Hunt, 2000; Wernerfelt, 1984; Wu et al., 2007), knowledge in the literature generally refers to the capacity of managers to apprehend and use relationships among informational factors to achieve intended ends (Autio et al.,

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

258

2000; Wu et al., 2007). Over time, the firm accumulates firm-specific knowledge internally (Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Teece & Pisano, 1994). Organizational knowledge obtained in this way from multiple individual sources is greater than the sum of its parts, and becomes a key strategic asset to the firm (Nelson & Winter, 1982). The knowledge base acquired in this way is idiosyncratic, and provides the firm with its competences (Nonaka, 1994; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). Knowledge is reinforced in all the activities of the firm, and becomes increasingly embedded in its routines (Autio et al., 2000). Through routinization of organizational activities, capabilities are embedded into organizational memory, engendering a unique configuration of firm resources and competences (Dev et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2007). However, the integration of particular types of knowledge depends on the nature and quality of the firms organizational routines, which involve continuous conversion of, especially, tacit knowledge (Polanyi, 1966) into business activities that create value for customers. Tacit knowledge is deeply embedded in individuals, and cannot be expressed explicitly or codified in written form (Nonaka, 1994). As a result, the unique and specific pathways that firms follow give rise to firm-specific knowledge bases and competences (Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Nelson & Winter, 1982; Nonaka, 1994). While capabilities typically emerge via the integration of unique knowledge embedded in individuals throughout the firm (Grant, 1991; Teece & Pisano, 1994), competences reflect the knowledgeintensive, performance-enhancing business activities in which the firm has become particularly skilled (Wu et al., 2007). Therefore the firms competences reflect its ability to perform repeatedly productive tasks that create value via the transformation of inputs into outputs (Nelson & Winter, 1982; Teece et al., 1997). Subsequently, organizational competences are the main source of the firms performance advantages (Dev et al., 2002; Grant, 1991; Wu et al., 2007). In international business, knowledge and particular organizational competences provide substantial advantages that facilitate foreign market entry and operations (e.g., Dev et al., 2002; Kogut & Zander, 1993; Johnson, Lenartowicz, & Apud, 2006). As firm resources, they lead to superior performance, particularly in highly competitive or challenging environments (Nelson & Winter, 1982). The most useful competences are those that

are rare, valuable, and difficult to imitate, as these will contribute maximally to superior organizational performance (Nelson & Winter, 1982; Teece et al., 1997). For resource-constrained international SMEs, therefore, firm competences are particularly important to the extent that they allow the firm to enter new (foreign) markets and devise effective ways of doing business in those markets.

RECOGNIZING IBC To empirically explore the above issues, we adopted a two-phase research design. In the first phase, we undertook exploratory research that combined case studies on a collection of international SMEs with a review of relevant literature, all intended to better understand contemporary international SMEs as well as to uncover key constructs and associated relationships. In the second phase, we conducted a survey-based study on a large sample of internationally active SMEs in order to validate findings from the qualitative phase. For the first phase, we conducted in-depth interviews with senior managers at 16 randomly selected SMEs that derive a substantial proportion of their revenues from international business, identified from the Directory of United States Exporters (available from the Journal of Commerce). Most of the interviewed firms were founded after 1985. They were selling half or more of their total sales abroad, and had internationalized within 3 years of founding. The interviews were conducted with the CEO or executive in charge of international operations within the firm. The interviews typically lasted about 45 min, and emphasized a collection of specific issues, including the nature of the firms internationalization process, posture in foreign markets, corporate culture in regards to internationalization, international strategic approaches, and generally the firms international success factors. The material obtained from the interviews was analyzed and organized according to patterns of consistent themes of firm culture, strategy, and performance. This analysis was initiated and carried out continuously after the first two interviews, in order to allow for refinements in the interview script, based on emerging themes and concepts. These data were supplemented with secondary material such as annual reports, brochures, and newspaper articles. Five of the interviewed firms marketed primarily consumer products, and eleven sold primarily industrial goods. On average, the interviewed firms had about 291 employees and

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

259

$54 million in annual sales. While a few of the interviews were conducted at the company sites, most were done by telephone, because respondent firms were dispersed throughout the United States. The case studies revealed particular types of competences that appear critical in the international performance of SMEs. The great majority of interviewed managers spoke about the importance of being internationally oriented, particularly when expanding abroad. They also highlighted the importance of developing and applying a strong marketing prowess in foreign ventures. They further indicated that success requires substantial innovativeness in the pursuit of international markets. Finally, they emphasized the importance of being sensitive to customers and markets, facilitated in part via efforts to understand customers and respond to their particular needs. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the case study results, we conceived that the most important organizational attributes in contemporary international SMEs are what we term international orientation, international marketing skills, international innovativeness, and international market orientation. The case studies suggested that these attributes are particularly important in the international performance of the contemporary SME. Collectively, we

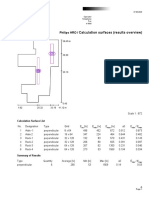

term them IBC. This conceptualization is summarized in Figure 1. The four factors are not expected to cause advantages, but are predicted to collectively reveal the latent, intangible construct IBC (cf. Bentler, 1995; Day, 1994; Hult & Ketchen, 2001). Other indicators are plausible, but the focus is on the present four because they emerged in case studies and, to some extent, from the literature review as strongly associated with SME international performance. In developing study hypotheses, we examined extant literature to uncover potential antecedents to performance in the international SME (e.g., Atuahene-Gima, 1995; Cadogan et al., 2002; Calantone & Knight, 2000; Coviello & McAuley, 1999; Knight, 2000; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Pelham & Wilson, 1996; Racela et al., 2007; Rialp & Rialp, 2006; Zahra et al., 2000). The emergent factors could be relevant to any internationalizing firm. However, findings from our exploratory investigation suggest that these factors are particularly important to the foreign market success of the growing category of international SMEs. The positional advantage that the four factors reveal is thought to be rare, valuable, and difficult to imitate. This adds further to their apparent role in engendering superior performance in the international SME.

International SME performance

Intl1 Intl2 Intl3 Intl4

International orientation

International market share H1a

Mkg1 Mkg2 Mkg3 Mkg4

International marketing skills

H1b International business competence H1c H1d

International sales growth

Inno1 Inno2 Inno3 Inno4 Inno5

International innovativeness

International profitability

CUS COM INT International market orientation

Export intensity

Figure 1

Conceptual framework and hypotheses.

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

260

DEFINING IBC The literature defines firm competence in multiple ways. Borrowing the definition of Teece et al. (1997), Day (1994: 38) views business competence as well-defined routines that are combined with firm-specific assets to enable distinctive functions to be carried out. Prahalad and Hamel (1990) argued that a firms effective interaction with markets is a core company competence (Johnson et al., 2006). Other researchers investigated alliance competence (Lambe, Spekman, & Hunt, 2002), nden, 2004), network competence (Ritter & Gemu interfirm partnering competence (Johnson & Sohi, 2003), cross-cultural competence (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2000; Johnson et al., 2006), intercultural communication competence (Bush, Rose, Gilbert, & Ingram, 2001), market knowledge competence (Li & Calantone, 1998), and various others (Dev et al., 2002). In the present study, IBC is conceptualized as a multidimensional concept that reflects the extent to which the SME adopts a bundle of international competences to carry out international business activities in foreign markets in an effective way. IBC emphasizes the SMEs possession of intangible, cultural orientations as well as processes that account for international business success. It reflects competences in multiple areas, including learning about international environments and adapting the entire organization to new environments through interactions with foreign markets. We discuss specific, emerged dimensions of IBC next.

International Orientation In the case studies, the great majority of SME managers spoke about the importance of having an aggressive, entrepreneurial approach to international markets. For example, a manager at a medical technology company noted: International business is risky; you have to be willing to take the risks and get out there y We go after our markets pretty aggressively. Another stated: You have to be pretty entrepreneurial and aggressive to succeed abroad. The business doesnt just come to you; you go out and find it. Collectively, we termed the construct expressed in such descriptions international orientation. Firms with a strong international orientation tend to possess distinctive competences and outlook (e.g., McDougall, Shane, & Oviatt, 1994; Mort & Weerawardena, 2006). They tend to be characterized by managerial vision and proactive organizational culture for developing particular resources

aimed at achieving company goals in foreign markets (e.g., Knight, 2000; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). For the SMEs that we interviewed, having an international orientation implies active exploration of new business opportunities abroad. Firms with limited tangible resources that are inclined to pursue foreign markets may need a strong international posture, in order to take the initiative to pursue new opportunities in complex markets, typically fraught with uncertainty and risk (Mort & Weerawardena, 2006). An international orientation is likely to give rise to certain processes, practices, and decision-making activities associated with targeting new markets abroad (Mort & Weerawardena, 2006) and thus possibly contributes to firm performance (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004).

International Marketing Skills The critical role of marketing prowess abroad also was strongly emphasized by virtually all SMEs in the case studies. One vice-president stated: We customize our products and our marketing for the overseas market y how we market our products is really important. Another noted: For us, advertising, direct sales, and promotional techniques are crucial y we have to be good at these. A vice president for international sales explained: In marketing, we put a lot of emphasis on execution, the actual handling of the product in the market y you have to merchandise your products well y get an ad agency with local expertise y You have to create demand and build your brand name. We conceptualize this as international marketing skills, which refer to a firms ability to create value for foreign customers through effective segmentation and targeting, and through integrated international marketing activities by planning, controlling, and evaluating how marketing tools are organized to differentiate offerings from those of competitors (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Johnson et al., 2006; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). Marketingrelated activities are known to engender superior organizational performance (e.g., Kotabe, Duhan, Smith, & Wilson, 1991). Within their markets, firms with good marketing skills attempt to offer products whose value buyers perceive to exceed the expected value of alternative offerings. The urge to continuously provide superior buyer value drives the firm to create and maintain a business culture that fosters the requisite business behaviors. Although SMEs might possess superior products and technology that meet the preferences of international customers well, they are less likely

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

261

to reach foreign customers effectively without strong marketing skills. As a result of globalization, buyers today are better organized, have more information, and are generally more demanding. Superior marketing skills assist companies to operate more effectively in such competitive international marketplaces. These skills provide the foundation through which the firm interacts with diverse foreign markets (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Zou & Cavusgil, 2002), enabling managers to create specific marketing-related strategies aimed at overcoming these challenges, and to adapt their various marketing strategies such as market positioning, forming partnerships, and locating distributors and retailers to local business environments more effectively. In sum, international marketing skills help the international SME reach and serve international customers more effectively.

International Innovativeness The next capability identified in the case studies is what we term international innovativeness. Most of the interviewed SMEs appeared to be strongly innovative, whether regarding their particular industrial or product category, or the approaches that they applied for entering foreign markets. For example, one manager stated that his firm provides state-of-the-art (heart surgery) products, y and in matters of life or death, people want the best. Another remarked: Our products are more competitive in Europe because theyre better designed, with better architecture, and more innovative. A third stated that his firm has employed methods for entering foreign markets that were pretty unusual and innovative. We define international innovativeness as the capacity to develop and introduce new processes, products, services, or ideas to international markets (Damanpour, 1991; Hurley & Hult, 1998; Kandemir & Hult, 2005). Zaltman, Duncan, and Holbek (1973) suggest that one of the stages of the innovativeness process is initiation and openness to the innovation (Calantone, Kim, Schmidt, & Cavusgil, 2006; Kandemir & Hult, 2005). Openness hinges on the degree to which members of an organization are willing to consider the adoption of an innovation or whether they are resistant to it. Van de Ven (1986) refers to this as the management of the organizations cultural attention in order to recognize the need for new ideas and action within the organization. Innovation results from two major sources: (1) internal R&D that draws on the firms accumulated

knowledge; and (2) market intelligence, including the innovations of other firms (Lewin & Massini, 2003; Nelson & Winter, 1982). Because an internationalizing firms learning may rely heavily on local sources of information, the role of market intelligence appears to be crucial for introducing innovations into foreign markets (Autio et al., 2000). In addition to introducing new goods and methods of production, R&D also supports the opening of new markets and reinventing the firms operations to serve those markets optimally (Nelson & Winter, 1982; Schumpeter, 1934). Much of the innovativeness in the international SME might hinge on the extent to which managers acquire and act on market intelligence. Organizations without the capacity to innovate may invest time and resources in studying markets, but are less able to translate this knowledge into practice. International innovativeness is a crucial dimension for successful international ventures, influencing the performance of international SMEs positively (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). In the expanded international market, technological leadership improves the competitiveness of firms that face local or regional firms as well as betterresourced MNEs. Coupled with a strong international orientation, it serves as a source of processes, products, and services that fit targeted international markets better (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Steensma, Marino, Weaver, & Dickson, 2000). Therefore international innovativeness is also a potential driver of SME performance in international markets (e.g., Kotabe, 1990; Porter, 1990).

International Market Orientation In the interviews, most SME executives also highlighted the importance of being oriented to foreign markets. One person noted that his company often does field surveys to find out what customers needs are and how to market products y Our philosophy has been to find out what customers need first, then design products to fit those needs y Thats been a factor in our success. Another noted that his company had developed a feedback loop early to learn about customers and competitors. Another stated that many potential customers had wanted to use his companys products but were held back by high prices. The firm responded with R&D that allowed it to bring down prices, and has since become number one in the world in its product category. An executive at another interviewed SME noted: Its really important to

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

262

understand the nuances of foreign markets y The ability to really understand the client, the market, and competitors, and then respond to that understanding is key. This is what the literature refers to as market orientation (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990). In defining market orientation, Kohli and Jaworski (1990) emphasized the organization-wide generation of market intelligence regarding customer needs, the dissemination of this intelligence throughout the firm, and organization-wide responsiveness to it. In a similar vein, Narver and Slater (1990) emphasized three behavioral components of market orientation customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination. Accordingly, we conceptualize international market orientation in the SME as the extent to which the firms international business activities are oriented toward customers and competitors, and the extent to which these activities are coordinated across functional areas in the firm (Hurley & Hult, 1998; Narver & Slater, 1990; Slater & Narver, 1994). Market orientation is a critical concept in marketing and management (Racela et al., 2007). The positive effect of market orientation on firm performance is well documented in domestic business settings (e.g., Pelham & Wilson, 1996; Slater & Narver, 1992) as well as in international settings, where the nature of customers and competitors is likely to vary substantially crossnationally (Cadogan et al., 1999; Calantone & Knight, 2000; Wren, Souder, & Berkowitz, 2000). For instance, Cadogan et al. (2002) found that firms with a foreign market orientation tend to achieve superior international performance. It seems equally critical for international SMEs to understand customers, competitors, and other market forces, and to disseminate learning about these entities within the organization (e.g., Cadogan et al., 2002; Calantone & Knight, 2000; Racela et al., 2007). In this process, market intelligence plays a crucial role. That is, because the nature of buyers and competitors abroad differs substantially from the domestic market, SMEs that rely on market intelligence to understand and serve customers abroad should experience superior performance. In firms with a strong market orientation, the knowledge obtained from market intelligence should also serve as a critical source of information for international innovativeness. Thus international market orientation should enhance SME performance abroad (Selnes, Jaworski, & Kohli, 1996; Wren et al., 2000).

IBC AND FIRM PERFORMANCE As indicated in Figure 1, we postulate that IBC reflects a firms capabilities to carry out international business activities effectively, and has a positive effect on international performance. Here we define international performance in terms of international market share, international sales growth, international profitability, and export intensity. International market share refers to the firms market share in international markets. International sales growth reflects the sales growth rate of the firm in the past 3 years in international markets. International profitability refers to the time span in years it took for the firm to become as profitable in international markets as in the domestic market. Export intensity is the ratio of export revenue to total sales. These indicators are the ones typically tracked by managers in assessing company performance, and have been used in numerous past studies (e.g., Calantone & Knight, 2000; Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Hult & Ketchen, 2001; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). In this study, these indicators will be evaluated independently, using a separate hierarchical model. Consistent with Hult and Ketchen (2001), this method facilitates a more thorough evaluation of the impact of IBC on each performance measure. It is preferred over a more traditional approach of assessing the effect of antecedents on some composite measure of performance. Supporting our model, the RBV identifies inimitability and immobility among the characteristics of firm resources that support sustainable competitive advantage (e.g., Barney, 1991). Fahy (2002) found that a firms intangible resources are important for competitive advantage in international business. As a bundle of business culture and processes, IBC is expected to serve as a source of competitive advantages, because it is difficult for competitors to replicate (Fahy, 2002). It is embedded in organizational processes, and thus is difficult for outsiders to observe (Barney, 1991; Li & Calantone, 1998). Furthermore, IBC is less likely to be perfectly mobile across organizations. It is developed over time within the firm, and is not available for purchase in the market. Therefore, consistent with the RBV, IBC is expected to offer the owning firm an important source of sustainable competitive advantage in international markets (Fahy, 2002). In a similar vein, the knowledge-based view also supports IBC as a crucial organizational factor for international SMEs. In particular, the view draws attention to the importance of tacit knowledge for

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

263

competitive advantage (Grant, 1996; McEvily & Chakravarthy, 2002) as well as the firms capability for integrating knowledge for successful organizational activities (Grant, 1996). According to this view, IBC is likely to serve as a source of competitive advantage since it concerns the SMEs tacit aspects culture, processes, routines, and knowledge that are difficult for competitors to replicate ( Johnson et al., 2006). Furthermore, IBC implicitly embraces the firms knowledge integration throughout its internationalization process, as international business activities involve ongoing learning ( Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Summarizing the ideas presented above, we contend that IBC, evidenced in international orientation, international marketing skills, international innovativeness, and international market orientation, positively affects the performance of the SME in international markets. Our case studies and a review of relevant literature imply that these competences, as compared with other possible ones, are especially salient to the international performance of the SME. Thus we offer the following hypotheses on the effect of IBC on individual elements of international SME performance: Hypothesis 1a: IBC positively affects international SME performance as evidenced in international market share. Hypothesis 1b: IBC positively affects international SME performance as evidenced in international sales growth. Hypothesis 1c: IBC positively affects international SME performance as evidenced in international profitability. Hypothesis 1d: IBC positively affects international SME performance as evidenced in export intensity. These hypotheses are evaluated subsequently in an empirical study.

METHODOLOGY To explore the proposed model, SMEs from multiple industries are included in the sampling frame. After conducting case study interviews with 16 representative SMEs actively involved in international business, we carried out an extensive literature search to locate measurement scales and information for each construct identified in the

case studies. Insights and inputs from the interviews were also used to develop a survey instrument. The resulting questionnaire was developed using seven-point Likert scales, following appropriate procedures (Churchill, 1979; Joreskog, Sorbom, Du Toit, & Du Toit, 2000; Nunnally, 1978). The measurement scales are presented in Table 1. For all construct measures, the unit of analysis was the firms most important export venture in its most important export market. The scale for international orientation was adapted from Khandwalla (1977), Covin and Slevin (1989), and Steensma et al. (2000). The scale for international marketing skills was based on the conceptualization of McKee, Conant, Varadarajan, and Mokwa (1992). The scale for international innovativeness was operationalized as a firms relative position to competitors in terms of technology leadership and technological innovativeness. The scale for international market orientation was adopted from Narver and Slater (1990). Lastly, the scale for firm performance was based on that of Cavusgil and Zou (1994). The resulting questionnaire was reviewed for face validity by a group of international business scholars. Next, a pilot study was conducted with 82 exporting SMEs for further refinement of the instrument. These firms were identified from the CorpTech Directory of Technology Companies, and were located around the United States. The completed questionnaires generated in this phase of the study were closely analyzed in order to further improve the survey instrument. Following this phase, a new sampling frame was developed for the main study from two databases: Directory of United States Exporters ( Journal of Commerce) and CorpTech Directory of Technology Companies. The final questionnaire was mailed to 900 randomly selected manufacturing SMEs in the United States whose export revenue was at least 25% or more of total sales. Although somewhat arbitrary, the 25% cut-off was established in light of the exploratory goals of the research and the attendant need to investigate highly international firms. It is more restrictive than the criteria used in previous studies to identify international firms, ranging from 5 to 10% (e.g., Autio et al., 2000; Zahra et al., 2000). Since the firms in the sampling frame are small to medium size, the CEO was targeted in each case and requested to have the survey completed by the individual most knowledgeable about export operations, if not the CEO. As an incentive, subjects were advised that money would be donated to charity for each returned survey. A total of 354 usable surveys

Journal of International Business Studies

Journal of International Business Studies

264

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Table 1

Measurement scales

Construct International orientation (1not at all; 7to an extreme extent)

CRZ 0.83

AVE 54.9%

Item Top management tends to see the world, instead of just the USA, as our firms marketplace The prevailing organizational culture at our firm (managements collective value system) is conducive to active exploration of new business opportunities abroad Management continuously communicates its mission to succeed in international markets to firm employees Management develops human and other resources for achieving our goals in international markets When confronted with international decision-making situations, we typically adopt a cautious, wait-and-see posture in order to minimize the chance of making costly mistakesa,b Management believes that, owing to the nature of the international business environment, it is best to explore it gradually via conservative, incremental stepsa,b In international markets, our top managers have a proclivity for high-risk projects (with chances for high returns)a Our top management is experienced in international businessa Management communicates information throughout the firm regarding our successful and unsuccessful customer experiences abroada Top management is willing to go to great lengths to make our products succeed in foreign marketsa Vision and drive of top management are important in our decision to enter foreign marketsa Marketing planning process Control and evaluation of marketing activities Skill to segment and target individual markets Ability to use marketing tools (product design, pricing, advertising, etc.) to differentiate this product Effectiveness of distributiona Knowledge of customers and competitorsa Development or adaptation of the producta Effectiveness of pricinga Advertising effectivenessa Image of your firma Locations of sales outletsa Ability to work well with distributorsa Ability to respond quickly to developing opportunitiesa

Standardized Loading 0.63 0.58

Source Covin and Slevin (1989), Khandwalla (1977), Miller and Friesen (1984)

0.83 0.88

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

International marketing skills In international markets, own firm rating relative to main competitors; 1much worse than main competitors; 7much better than main competitors

0.81

51.4%

0.77 0.74 0.64 0.71

Adapted from McKee, Conant, Varadarajan, and Mokwa (1992)

Table 1

continued

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Construct

CRZ

AVE

Item

Standardized Loading 0.69 0.62 0.74 0.66 0.83

Source

International innovativeness (1not at all; 7to an extreme extent)

0.84

50.7%

Our firm is at the leading technological edge of our industry in international markets We invented a lot of the technology embedded in this product Our firm is highly regarded for its technical expertise among our channel members in international markets In the design and manufacture of this product, we employ some of the most skilled specialists in the industry We are recognized in international markets for products that are technologically superior Compared with local competitors, were often first to introduce product innovations or new operating approaches in international marketsa Over the past 5 years, our firm has marketed very many products in foreign marketsa Customer orientation Management communicates information throughout our firm about our successful and unsuccessful customer experiences in this market All our managers understand how everyone in our firm can contribute to creating value for the customers in this market Competitor orientation Top management frequently discusses the strengths and weaknesses of our major competitor(s) there If a competitor launched an intensive campaign targeted at our customers there, we would implement a response immediately Interfunctional orientation Our business functions (e.g., marketing/sales, manufacturing, finance) are integrated in serving the needs of this market Our strategy for competitive advantage in this market is based on our understanding of customer needs therea Our strategies in this market are driven by our beliefs about how we can create value for customersa For us, success in this market is driven by truly satisfying the needs of our customers therea We systematically assess customer satisfaction in this market at least once a yeara We ensure that close attention is given, in this market, to after-sales servicea Our firm responds quickly, throughout the organization, to negative customer satisfaction information regarding this marketa

International market orientation (1not at all; 7to an extreme extent)

0.82

53.9%

0.89 0.86

0.85 0.92 0.78 0.72 0.98 0.73

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

Journal of International Business Studies

CFA fit indexes: chi-square280.104 on 126 d.f.; NNFI0.934; CFI0.946; SRMR0.046; RMSEA0.059. All standardized coefficient loadings are significant at po0.01. CRZcomposite reliability. AVEaverage variance extracted. a Indicates items that were dropped in the scale purification process. b Indicates reverse-polarity items

265

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

266

were returned in three waves, an effective response rate of about 39%. Nonresponse bias was assessed by dividing responses into two groups. Early and late respondents were compared using a t-test to identify potential differences on key variables (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). Furthermore, we compared number of employees, firm age calculated from the founding year, total sales, product category, return on investment, sales growth, and market share in main export market between randomly chosen samples of responding and nonresponding firms. No significant differences were found in these t-tests (p40.05), and thus nonresponse bias is not likely to affect results. Respondent firms represent a range of industries that manufacture various products, such as medical devices, coiled steel tubing, computer software, textile printing blankets, and oil field chemicals. The average firm had 190 employees and generated $32 million in total sales in other words, typical SMEs. Foreign sales accounted for an average of 41% of total sales, with firms targeting some 20 countries at the median. To assess the quality of measures, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using EQS for Windows 5.7b (Bentler, 1995). Because of the exploratory nature of the study, we first ran a CFA on three dimensions (international orientation, international marketing skills, and international innovativeness) of IBC as first-order constructs, and international market orientation, the fourth dimension of IBC, as a second-order construct with customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional orientation included as first-order constructs of international market orientation. In this CFA model, IBC, the higher-order construct, is not specified yet to assess the adequacy of the four dimensions of IBC as valid constructs only. The results after a measurement purification process (Table 1) revealed a chi-square of 280.104 on 126 degrees of freedom (d.f.), non-normed fit index (NNFI) of 0.934, comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.946, standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR) of 0.046, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.059. These suggest that the four elements of IBC fit the empirical covariances provided by the sample very well (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Subsequently, the unidimensionality of each construct was assessed by investigating the standardized loadings for convergent validity, average variance extracted compared with shared variances at the construct level for discriminant validity, and

composite reliability for measurement reliability. The CFA results reveal that all loadings were greater than 0.50 and significant (po0.05), as reported in Table 1. This indicates an adequate level of convergent validity (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). For discriminant validity, we calculated average variance extracted for each construct and shared variances between constructs (Fornell & Larker, 1981). Table 2 shows intercorrelations and shared variances of the measures. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, no average variance extracted is less than shared variance between relevant constructs, and all average variance extracted values are greater than 0.50 (Fornell & Larker, 1981). These results imply that discriminant validity of constructs was achieved. As a final step to assess the validity and adequacy of each construct, we calculated composite reliabilities (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Fornell & Larker, 1981). Table 1 presents composite reliabilities and the standardized parameters of measurement scales. All composite reliabilities are greater than 0.80, above the generally acceptable level of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). These results reveal that an adequate level of construct validity was achieved. Next, we assessed the validity of the higher-order construct, IBC, by estimating another CFA model with the three first-order constructs (international orientation, international marketing skills, and international innovativeness) and one second-order construct (international market orientation) as indicators of IBC. The results, reflected in Table 3, provide a chi-square of 290.787 on 129 d.f., NNFI of 0.932, CFI of 0.943, SRMR of 0.053, and RMSEA of 0.060. Although most fit indexes decreased negligibly, the fit indexes of this higher-order model still indicate that the higher-order model also fits with the empirical covariances provided by the data set very well (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Subsequently, we assessed the validity of IBC as a higher-order construct. According to the results, international orientation (loading0.72), international marketing skills (loading0.66), international innovativeness (loading0.51), and international market orientation (loading0.97) are all significant indicators (po0.01) of the higher-order construct IBC, revealing a good level of convergent validity for IBC, as reported in Table 3. Furthermore, its composite reliability of 0.82 coupled with average variance extracted of 0.539 indicates that IBC as a higherorder construct has a good level of construct validity. With the acceptable measurement model, we estimated our theoretical model with IBC as a

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

267

Table 2

Intercorrelations and shared variances of measures (n354)

1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 International orientation International marketing skills International innovativeness International market orientation International market share International sales growth International profitability Export intensity 0.42 0.34 0.71 0.25 0.24 0.18 0.37

2 0.18 0.46 0.64 0.36 0.32 0.27 0.10

3 0.12 0.21 0.47 0.30 0.27 0.32 0.12

4 0.50 0.41 0.22 0.28 0.29 0.31 0.17

5 0.06 0.13 0.09 0.08 0.83 0.58 0.27

6 0.06 0.11 0.07 0.08 0.69 0.59 0.23

7 0.03 0.07 0.10 0.09 0.34 0.35 0.15

8 0.14 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.07 0.05 0.02

The correlations are in the lower triangle of the matrix. Shared variances are in the upper triangle of the matrix.

Table 3

International business competence as a higher-order construct

Construct International business competence

CRZ 0.82

AVE 53.9%

Item International International International International orientation marketing skills innovativeness market orientation

Standardized Loading 0.72 0.66 0.51 0.97

CFA fit indexes: chi-square290.787 on 129 d.f.; NNFI0.932; CFI0.943; SRMR0.053; RMSEA0.060. CRZcomposite reliability. AVEaverage variance extracted.

higher-order construct for each of the performance variables. That is, we estimated a separate hierarchical model for each performance measure to evaluate the impact of IBC more effectively (Hult & Ketchen, 2001). Final study results are reported in Table 4.

Hypothesis 1a is supported. The control variable, firm size, does not affect international market share significantly (p40.10).

IBC and International Market Share We estimated a model with IBC as a higher-order construct and international market share as a performance measure. In this theoretical model, we also included firm size, measured by number of full-time employees, as a control variable. The results suggest an excellent fit of the model to the data, with a chi-square393.81 on 164 d.f., NNFI0.91, CFI0.92, and RMSEA0.063. Furthermore, as lower-order indicators, international orientation (standardized loading0.71, R20.51), international marketing skills (standardized loading0.71, R20.51), international innovativeness (standardized loading0.55, R20.30), and international market orientation (standardized loading0.93, R20.86) all loaded significantly on IBC, the higher-order construct (po0.01). Finally, results reveal that IBC affects firm international market share positively with standardized coefficient0.41, t6.00, explaining about 17% of variance in the dependent variable. Therefore,

IBC and International Sales Growth We next estimated a model with international sales growth as a performance measure, retaining firm size as the control variable. Results revealed an excellent fit of the model to the data, with a chisquare380.49 on 164 d.f., NNFI0.91, CFI93, and RMSEA0.062. As above, international orientation (standardized loading0.71, R20.51), international marketing skills (standardized loading 0.70, R20.49), international innovativeness (standardized loading0.54, R20.29), and international market orientation (standardized loading0.94, R20.89) as indicators of IBC all loaded significantly on IBC (po0.01). Moreover, IBC affects firm international sales growth positively with standardized coefficient0.37, t5.64, explaining about 14% of the variance. Therefore, Hypothesis 1b is supported. Firm size does not significantly affect international sales growth (p40.10). IBC and International Profitability A model with international profitability as a performance variable and firm size as a control

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

268

Table 4

Summary of the results

Lower-order constructs

Loading on IBC

Beta coefficient (IBC-DV)

R2

Fit indexes

Chi-square (d.f.) Model 1 (DVInternational market share) International orientation 0.71 International marketing skills 0.71 International innovativeness 0.55 International market orientation 0.93 Model 2 (DVInternational sales growth) International orientation 0.71 International marketing skills 0.70 International innovativeness 0.54 International market orientation 0.94 Model 3 (DVinternational profitability) International orientation 0.72 International marketing skills 0.69 International innovativeness 0.54 International market orientation 0.95 Model 4 (DVinternational export intensity) International orientation 0.74 International marketing skills 0.68 International innovativeness 0.52 International market orientation 0.94

DVdependent variable. **Significant at 0.01.

NNFI

CFI

RMSEA

Hypothesis Hypothesis supported?

0.41**

0.17 393.81 (164) 0.91

0.92

0.063

H1a

Yes

0.37**

0.14 380.49 (164) 0.91

0.93

0.062

H1b

Yes

0.38**

0.14 388.16 (164) 0.91

0.92

0.063

H1c

Yes

0.33**

0.08 422.56 (164) 0.90

0.91

0.068

H1d

Yes

variable was estimated next. Results reveal an excellent fit of the model to the data, with a chi-square388.16 on 164 d.f., NNFI0.91, CFI0.92, and RMSEA0.063. As above, international orientation (standardized loading0.72, R20.50), international marketing skills (standardized loading0.69, R20.47), international innovativeness (standardized loading0.54, R20.29), and international market orientation (standardized loading0.95, R20.91) as indicators of IBC all loaded significantly on IBC (po0.01). Furthermore, IBC affects firm international profitability positively with a standardized coefficient0.38, t5.70, explaining about 14% of variance. Therefore, Hypothesis 1c is supported. Firm size as the control variable does not affect international profitability (p40.10).

excellent fit of the model to the data, with a chisquare422.56 on 164 d.f., NNFI0.90, CFI0.91, and RMSEA0.068. International orientation (standardized loading0.74, R20.55), international marketing skills (standardized loading0.68, R20.46), international innovativeness (standardized loading0.52, R20.27), and international market orientation (standardized loading0.94, R20.87) all loaded on IBC (po0.01). The results further indicate that IBC affects a firms export intensity positively with standardized coefficient 0.33, t4.29, explaining about 8% of variance. Thus, Hypothesis 1d is also supported. Firm size reveals no significant effect on export intensity (p40.10).

IBC and Export Intensity Finally, we estimated a model with export intensity as the performance variable and firm size as a control variable. The results indicate another

DISCUSSION Cast in an evolutionary economics framework (Nelson & Winter, 1982), our findings suggest how particular organizational capabilities can support superior performance in diverse international markets in the international SME. Our results provide empirical evidence that contemporary

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

269

smaller firms that possess a high level of IBC perform better internationally. IBC leads to superior SME performance in international sales growth, international market share, international profitability, and export intensity. That is, IBCs impact across various performance variables is consistent. The results suggest that SMEs can enhance their performance internationally and thus their overall performance by establishing and skillfully managing IBC. These results offer theoretical and managerial implications. Theoretically speaking, our findings suggest that, in order to be successful in international business, international SMEs should develop specific competences that are relatively unique and inimitable, in order to maximize their utility for international performance. Possession of IBC leads to the development of specific organizational capabilities, consisting of critical competences and embedded routines. IBC reflects superior firm resources, such as in-house local market knowledge (Johnson et al., 2006), and superior strategies that are undertaken by skilled personnel. As the resource-based perspective highlights, a firms foundational resources, including key competences, are important in diverse business environments because they provide a stable basis for the development of specific competences. These competences will be particularly useful to the extent that they are embedded in organizational culture via ongoing replication of routines, producing a unique configuration of resources. Our results also suggest that a firms IBC is a multidimensional construct that taps specific internal competences of the contemporary SME, such as business culture and capabilities, that are critical to its international performance, with considerable relevance to the firms internal and external business environments. Although SMEs tend to lack substantial financial and tangible resources, those that succeed internationally appear to leverage a collection of more fundamental, intangible resources, reflected in IBC. Those key intangible resources, as dimensions of IBC, include international orientation, international marketing skills, international innovativeness, and international market orientation. Although there are undoubtedly other competences instrumental to the international SME, our findings from case and survey-based studies indicate that these factors are particularly salient. They are distinctive lower-order constructs that reveal the level of firms IBC. Of these four dimensions, international market orientation and international orientation appear to

have the highest loadings on IBC. We assessed the statistical significance of such differences. According to the results, international market orientation loads on IBC more significantly than any of the other three dimensions across the four different models (po0.01). International orientation loads on IBC more significantly than international innovativeness in the models in which international sales growth (po0.10) and export intensity (po0.05) are the dependent performance variables. International marketing skills also loads on IBC more significantly than international innovativeness across all four models (po0.05). To sum up, international market orientation and international orientation seem to be the strongest indicators of IBC, followed by international marketing skills. Although a significant indicator, international innovativeness does not reveal IBC as well as the other three constructs do. Managerially speaking, study results reveal that international performance and the ultimate survival of the firm appear to hinge on the development and well-conceived manipulation of a particular set of competences. SMEs are smaller firms, often relatively new to international business. They tend to lack the large base of financial and tangible resources that characterize the traditional MNE. The specific competences identified here help international SMEs to overcome the scarcity of traditional resources to succeed in foreign markets. The quality of the management team in international SMEs, in particular, is likely to hold particular relevance for company success. The competences embedded in management are born of specific circumstances, causal relationships, and a unique social structure within each SME. Similarly, results indicate that IBC may be relatively distinctive. The specialized approaches inherent in IBC are held by individual managers or embedded within the internationally successful small firm. In short, IBC comprises a collection of firm-specific capabilities that are imperfectly imitable by wouldbe rival firms. The study findings suggest that, among the four dimensions investigated here, a firms IBC is more strongly reflected in international market orientation and international orientation. Compared with the other lower-order constructs, international market orientation and international orientation may have a wider scope of influence on SME business activities. That is, having a strong international orientation can shape organizational culture, while international market orientation covers

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

270

a firms internal efforts to collect and disseminate market intelligence on foreign customers and competitors, and to coordinate functional areas internally for international business activities. SME managers should configure their intangible resources so as to emphasize international orientation and international market orientation. This study investigated IBC comprehensively as a higher-order construct in which multiple key lower-order indicators are identified. The comprehensive approach followed in this study offers several advantages over the disaggregated approach in the literature. First, it provides managers with a way to assess their competence in international markets more effectively. Managers are able to examine how multiple factors simultaneously form firms IBC. In addition, the approach supports the notion that a firm is a bundle of resources. Given the complex structure of IBC, it is relatively more difficult for competitors to replicate such a comprehensive approach. Finally, a complex approach is more realistic because firms adopt goals and strategic visions that affect their culture and various capabilities simultaneously across the entire organization. While globalization and emergent technologies facilitate an environment in which more smaller firms are expected to internationalize, many such enterprises remain wedded to their home markets. Our findings suggest a way forward for SME managers currently focused on their domestic market but who wish to expand abroad. They also suggest how currently active international SMEs might internationalize further and improve their international performance. In light of the findings presented here, such firms should seek to develop IBC, and the particular competences that it represents. We have highlighted these competences and empirically confirmed their explanatory value among a large sample of international SMEs. Managers at SMEs with international aspirations are advised to begin with a global vision, and devise a collection of competences that reflect IBC.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH We acknowledge limitations of the current study, which may help scholars in developing future research. First, although this study identified four distinctive dimensions of IBC, there are likely to be additional relevant dimensions. Future research should investigate additional dimensions. For example, one possible dimension is the global commitment that SMEs make. Second, the ante-

cedents of IBC are yet to be explored. Even though we identified four critical dimensions, future research needs to investigate internal and external factors of SMEs that influence IBC. We conjecture that a firms management characteristics could be an important internal factor for IBC, and market and/or technological turbulence could play roles as external factors. Third, even though this study argued and reported an overall positive effect of IBC on SME profit, it may have a partial negative effect on profit as the firms efforts to enhance IBC incur costs, which will affect profitability negatively. Future research should identify when the overall effect of IBC turns negative by incorporating moderators such as industry type and level of competition. Finally, we adopted ultimate outcome measures in evaluating the impact of IBC on firm performance. However, there could be other immediate outcome measures of IBC, including international customer satisfaction, brand awareness, and customer loyalty. These customer-based immediate outcome measures would offer more detailed explanations on how IBC leads to firm performance. Thus future research should aim at exploring IBCs effect on customer satisfaction by obtaining performance data from consumers. During the past couple of decades, the volume of global business activity has increased dramatically, and is associated with the emergence of mechanisms and infrastructures that are facilitating the internationalization of countless smaller firms. The development of technologies that allow companies to internationalize and conduct global business efficiently is hastening this trend. The emergence of international SMEs is encouraging, because it suggests that any firm, regardless of its size and base of tangible resources, can be an active player in international business. The emergence of such firms heralds the arrival of a more diverse international business system in which any firm can succeed internationally. To the extent that more SMEs succeed in international business, they can gradually challenge other, larger firms that have traditionally excelled abroad. Future research should aim at deepening understanding of international SMEs, which represent a widespread, emergent trend. Future research should also investigate the characteristics and behaviors of born-global firms (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Rialp & Rialp, 2006), and the liabilities of newness, smallness, and foreignness (Autio et al., 2000; Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997). SMEs are smaller firms, often relatively new

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

271

in international markets. Although the specific competences identified here help international SMEs overcome the scarcity of traditional resources needed to succeed abroad, additional research on such topics can help clarify the most appropriate approaches that small firms should follow to ensure superior performance.

CONCLUSION Internationalization is no longer optional for most firms today. How firms can reposition themselves to be internationally competent is of great interest to managers and researchers. By exploring how a firms IBC is materialized within the firm as a

culture and as a behavioral tendency, this study contributes to our understanding of the contemporary international firm. This study investigated SMEs international orientation, international marketing skills, international innovativeness, and international market orientation as the lower-order indicators of IBC, and reported that they all reflect the business competence of small firms in international markets. We linked IBC to SME performance variables empirically, suggesting that IBC as an intangible firm resource affects firm performance positively. We hope that this study provides the basis for future research on the concept of IBC, particularly on behalf of the international SME.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3): 411423. Armstrong, J., & Overton, T. 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3): 396402. Atuahene-Gima, K. 1995. The influence of new product factors on export propensity and performance: An empirical analysis. Journal of International Marketing, 3(2): 1128. Autio, E., Sapienza, H., & Almeida, J. 2000. Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5): 909924. Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1): 7494. Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1): 99120. Bentler, P. 1995. EQS: Structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software Inc. Brady, D. L., & Bearden, W. O. 1979. The effect of managerial attitudes on alternative exporting methods. Journal of International Business Studies, 10(3): 7984. Bush, V. D., Rose, G. M., Gilbert, F., & Ingram, T. N. 2001. Managing culturally diverse buyerseller relationships: The role of intercultural disposition and adaptive selling in developing intercultural communication competence. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 29(4): 391404. Cadogan, J. W., Diamantopoulos, A., & de Mortanges, C. P. 1999. A measure of export market orientation: Scale development and cross-cultural validation. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(4): 689707. Cadogan, J. W., Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. 2002. Export market-oriented activities: Their antecedents and performance consequences. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3): 615626. Calantone, R., & Knight, G. 2000. The critical role of product quality in the international performance of industrial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(6): 493506. Calantone, R., Kim, D., Schmidt, J., & Cavusgil, S. T. 2006. The influence of internal and external firm factors on international product adaptation strategy and export performance: A three-country comparison. Journal of Business Research, 59(2): 176185. Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. 1994. Marketing strategyperformance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1): 121. Churchill, G. A. 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1): 6473. Chuushoo Kigyoo Cho 1995. Chuushoo kigyoo hakushoo (White paper on small and medium-size enterprise). Tokyo: Okura-sho Insatsu Kyoku (Treasury Department, Government of Japan). Collis, D. 1991. A resource-based analysis of global competition. Strategic Management Journal, 12(Summer Special Issue): 4968. Coviello, N., & McAuley, A. 1999. Internationalisation and the smaller firm: A review of contemporary empirical research. Management International Review, 39(3): 223256. Covin, J., & Slevin, D. 1989. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1): 7587. Craig, C. S., & Douglas, S. P. 1996. Developing strategies for global markets: An evolutionary perspective. Columbia Journal of World Business, 31(1): 7081. Czinkota, M. 1982. Export development strategies: US promotion policies. New York: Praeger Publishers. Damanpour, F. 1991. Organizational innovation: A metaanalysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3): 555590. Day, G. S. 1994. The capabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4): 3752. Dev, C. S., Erramilli, M. K., & Agarwal, S. 2002. Brands across borders: Determining factors in choosing franchising or management contracts for entering international markets. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(6): 91104. Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. 1989. Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12): 15041510. Fahy, J. 2002. A resource-based analysis of sustainable competitive advantage in a global environment. International Business Review, 11(1): 5778. Fornell, C., & Larker, D. F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1): 3950. Grant, R. M. 1991. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3): 114135. Grant, R. M. 1996. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(Winter Special Issue): 109122. Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. 2000. Building crosscultural competence: How to create wealth from conflicting values. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Journal of International Business Studies

International business competence and the contemporary firm

Gary A Knight and Daekwan Kim

272