Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Eurotech Hair Systems, Inc. vs. Go

Transféré par

vanessa3333333Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Eurotech Hair Systems, Inc. vs. Go

Transféré par

vanessa3333333Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

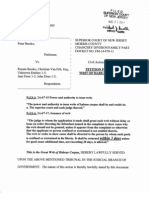

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila THIRD DIVISION G.R. No.

160913 August 31, 2006 EUROTECH HAIR SYSTEMS, INC., LUTZ KUNACK, and JOSE BARIN, Petitioners, vs. ANTONIO S. GO, Respondent. RESOLUTION QUISUMBING, J.: For review on certiorari are the Decision 1 dated July 9, 2003 and the Resolution 2 dated November 19, 2003, of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 69909 setting aside the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) Decision 3 but reinstating with modification the Decision 4 of the Labor Arbiter. The facts are as follows: Petitioner Eurotech Hair Systems, Inc. is a domestic corporation engaged in the manufacture and export of wigs and toupees. Petitioners Lutz Kunack and Jose E. Barin are the companys pr esident and general manager, respectively. Respondent Antonio S. Go served as Eurotechs operations manager from September 2, 1996 until he was dismissed on September 27, 1999. As operations manager, he drafted and implemented the plans for the production of wigs and toupees. Respondents responsibilities included manpower planning to meet the monthly production targets. In 1999, the company suffered production shortfalls. Thus, on September 2, 1999, petitioner Barin issued respondent a memorandum, strongly advising him to improve his performance. He was also admonished because of the late shipment of 80 units of hairpieces to one of petitioners clients, Bergmann Company. On September 7, 1999, Eurotech issued another memorandum reiterating the previous reminder for respondent to improve his performance. Again, on September 21, 1999, Eurotech issued two memoranda, reminding respondent of his continued failure to improve his performance. He was given 24 hours to explain in writing why the company should not terminate his services on the ground of loss of trust and confidence. On September 22, 1999, Eurotech relieved respondent as operations manager pending evaluation of his performance. On September 24, 1999, Eurotech issued yet another memorandum reminding respondent of his failure to submit his written explanation and granting him another 24 hours to submit such explanation. The second 24-hour period lapsed without respondents explanation. On September 27, 1999, petitioner Kunack finally issued respondent a t ermination letter citing loss of trust and confidence. Consequently, respondent filed against petitioners a complaint docketed as NLRC Case No. RAB-IV-10-11565-99-L for illegal dismissal, separation pay, backwages, and damages. 5 The Labor Arbiter ruled for respondent. On appeal, the NLRC reversed the Labor Arbiter and dismissed the complaint for lack of merit. 6 Respondents motion for reconsideration was denied. Hence, respondent elevated the matter to the Court of Appeals. The appellate court set aside the decision of the NLRC and essentially reinstated the ruling of the Labor Arbiter. Respondent received said Decision of the Court of Appeals on July 21, 2003. Prior to such receipt, he had executed a quitclaim 7 in consideration of P450,000. Hence, on July 16, 2003, the Labor Arbiter issued an Order 8 dismissing with prejudice the complaint for illegal dismissal in view of the said waiver. Petitioners thus moved for reconsideration of the Court of Appeals decision in light of the said settlement. Responde nt, on the other hand, manifested that he was not represented by his counsel when he signed the quitclaim. He further alleged that he was in fact advised by petitioners not to inform his counsel about the quitclaim. The Court of Appeals denied the motion for reconsideration for lack of merit and voided for lack of jurisdiction the Labor Arbiters Order dismissing the case with prejudice. Hence, the instant petition raising the following issues: A WHETHER OR NOT THE NLRC EXHIBITED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN RENDERING ITS DECISION DATED 30 JULY 2001 AND ITS ORDER DATED 20 DECEMBER 2001. 1. Whether or not respondents Petition for Certiorari prayed for the Court of Appeals correction of the NLRCs evaluation o f the evidence without establishing where the grave of abuse lies. 2. Whether or not the findings of facts by the NLRC are conclusive upon the Court of Appeals, which can no longer be disturbed. B WHETHER OR NOT THE JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEALS HAD LEGAL BASIS AND WAS BASED ON GROSS MISAPPRECIATION OF FACTS. 1. Whether or not the NLRC correctly ruled that there was sufficient and legitimate basis to terminate the services of respondent for his gross incompetence resulting in the Companys loss of confidence on said employee. 2. Whether or not the Court of Appeals had substantial basis to support its judgment.

3. Whether or not the Court of Appeals ruling has violated the Companys constitutional right to reasonable returns on its investments. 4. Whether or not respondent was afforded the required procedural due process. C WHETHER OR NOT THE COURT OF APPEALS HAD LEGAL BASIS IN HOLDING THAT THE LABOR ARBITER DID NOT HAVE JURISDICTION TO DISMISS THE CASE IN VIEW OF THE COMPROMISE AGREEMENT REACHED BETWEEN THE PARTIES. 9 Simply put, the issues now for our resolution are: (1) Was respondents dismissal in accordance with law? and (2) Is the compromise agreement entered into by the parties valid? Petitioners contend the NLRC correctly ruled there was legitimate basis to terminate respondent for gross incompetence resulting in the companys loss of confidence in him. But petitioners also claim that the Court of Appeals ruling effectively violated their constitutional right to reasonable returns on investment. They allege that the evidence on record shows respondent was afforded the required procedural due process. Petitioners likewise contend that the pendency of respondents petition for certiorari before the Court of Appeals did not di vest the Labor Arbiter of jurisdiction to dismiss the case in view of the quitclaim. They add that respondent knowingly and voluntarily executed the waiver in the presence of the Labor Arbiter. Petitioners further allege that the compromise agreement has the force and effect of res judicata. Respondent, for his part, counters that there was no legal or factual basis to terminate him on the ground of loss of trust and confidence. He argues that allowing an employer to dismiss an employee on a simple claim of loss of trust and confidence places the employees right to security of tenure at the mercy of the employer. Respondent further contends that the petition raises only questions of fact and should therefore be denied outright. Finally, he assails the Court of Appeals deletion of the award of attorneys fees. He argues that s ince moral and exemplary damages have been awarded to respondent, an award of attorneys fees is proper under Article 2208 10 of the Civil Code. Considering all the circumstances in this case, we find the present petition meritorious. Loss of trust and confidence to be a valid ground for an employees dismissal must be based on a willful breach and founded on clearly established facts. A breach is willful if it is done intentionally, knowingly and purposely, without justifiable excuse, as distinguished from an act done carelessly, thoughtlessly, heedlessly or inadvertently. 11 While failure to observe prescribed standards of work, or to fulfill reasonable work assignments due to inefficiency may be a just cause for dismissal, 12 the employer must show what standards of work or reasonable work assignments were prescribed which the employee failed to observe. In addition, the employer must prove that the employees failure to observe any such standard s or assignments was due to his own inefficiency. 13 In this case, petitioners showed that respondent failed to meet production targets despite reminders to measure up to the goals set by the company. However, they were unable to prove that such failure was due to respondents inefficiency. Significant factors that might explain the companys poor production include existing market conditions at the time, the overall spending behavior of consumers, and the prevailing state of the countrys economy as a whole. The companys production shortfalls cann ot be attributed to respondent alone, absent any showing that he willfully breached the trust and confidence reposed in him by the petitioners. Note that the burden of proof in dismissal cases rests on the employer. 14 In the instant case, however, petitioners failed to prove that respondent was terminated for a valid cause. Evidence adduced was utterly wanting as to respondents alleged inefficienc y constituting a willful breach of the trust and confidence reposed in him by petitioners. However, on the second issue, we find for petitioners. Article 227 of the Labor Code provides: ART. 227. Compromise agreements. Any compromise settlement, including those involving labor standard laws, voluntarily agreed upon by the parties with the assistance of the Bureau or the regional office of the Department of Labor, shall be final and binding upon the parties. Note, however, that even if contracted without the assistance of labor officials, compromise agreements between workers and their employers remain valid and are still considered desirable means of settling disputes. 15 A compromise agreement is valid as long as the consideration is reasonable and the employee signed the waiver voluntarily, with a full understanding of what he was entering into. All that is required for the compromise to be deemed voluntarily entered into is personal and specific individual consent. Thus, contrary to respondents contention, the employees counsel need not be prese nt at the time of the signing of the compromise agreement. In this case, we find the consideration of P450,000 fair and reasonable under the circumstances. In addition, records show that respondent gave his personal and specific individual consent with a full understanding of the stakes involved. In our view, the compromise agreement in this case does not suffer from the badges of invalidity. The fact that the Order, which dismissed the case in view of the compromise agreement, was issued during the pendency of the petition for certiorari in the Court of Appeals does not divest the Labor Arbiter of jurisdiction. A petition for certiorari is an original action and does not interrupt the course of the principal case unless a temporary restraining order or a writ of preliminary injunction has been issued against the public respondent from further proceeding. 16 The Labor Arbiter thus acted well within his jurisdiction. Therefore, the Labor Arbiters Order dismissing the case with prejudice in view of the compromise agreement ent ered into by the parties must be upheld. WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The assailed Decision dated July 9, 2003 and Resolution dated November 19, 2003, of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 69909 are SET ASIDE. The July 16, 2003 Order of the Labor Arbiter in NLRC Case No.

RAB-IV-10-11565-99-L dismissing the case with prejudice is AFFIRMED. No costs. SO ORDERED. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Associate Justice WE CONCUR: ANTONIO T. CARPIO Associate Justice CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Associate Justice DANTE O. TINGA Associate Justice

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR. Associate Justice ATTESTATION I attest that the conclusions in the above Resolution had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Courts Division. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Associate Justice Chairperson CERTIFICATION Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the Division Chairpersons Attestation, I certify that the conc lusions in the above Resolution had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Courts Division. ARTEMIO V. PANGANIBAN Chief Justice

Footnotes

1

Rollo, pp. 60-72. Penned by Associate Justice Oswaldo D. Agcaoili, with Associate Justices Perlita J. Tria Tirona, and Edgardo F. Sundiam concurring.

2

Id. at 74-77. Id. at 79-95. Id. at 117-122. Id. at 115. Id. at 94. Id. at 569. Id. at 96. Id. at 520-521.

10

Art. 2208. In the absence of stipulation, attorneys fees and expenses of litigation, other than judicial costs, cannot be recovered, except: (1) When exemplary damages are awarded; (2) When the defendants act or omission has compelled the plaintiff to litigate with third persons or to incur expenses to p rotect his interest; xxxx (5) Where the defendant acted in gross and evident bad faith in refusing to satisfy the plaintiffs plainly valid, just and demandable claim; xxxx (7) In actions for the recovery of wages of household helpers, laborers and skilled workers; xxxx

11

Asia Pacific Chartering (Phils.), Inc. v. Farolan, G.R. No. 151370, December 4, 2002, 393 SCRA 454, 466.

12

Buiser v. Leogardo, Jr., No. L-63316, July 31, 1984, 131 SCRA 151, 158. Asia Pacific Chartering (Phils.), Inc. v. Farolan, supra note 11 at 467-468. Athenna International Manpower Services, Inc. v. Villanos, G.R. No. 151303, April 15, 2005, 456 SCRA 313, 320. Galicia v. NLRC (Second Division), G.R. No. 119649, July 28, 1997, 276 SCRA 381, 387. Tomas Claudio Memorial College, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 152568, February 16, 2004, 423 SCRA 122, 132.

13

14

15

16

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Bresko Habeas Corpus 8-26-11Document132 pagesBresko Habeas Corpus 8-26-11pbresko100% (1)

- Feudalism WorksheetDocument3 pagesFeudalism WorksheetRamesh Adwani100% (1)

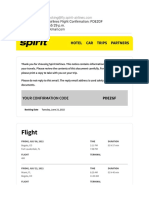

- Modified Spirit Airlines Flight Confirmation PDEZGFDocument7 pagesModified Spirit Airlines Flight Confirmation PDEZGFASTRIDH CHACONPas encore d'évaluation

- Territorial Disputes Over The South China SeaDocument46 pagesTerritorial Disputes Over The South China SeaTan Xiang100% (1)

- Dreams Are Broken Into Three Parts According To The SunnahDocument19 pagesDreams Are Broken Into Three Parts According To The SunnahpakpidiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Court rules action for forcible entry is in personamDocument2 pagesCourt rules action for forcible entry is in personamBenneth SantoluisPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax 1 ReviewerDocument52 pagesTax 1 Reviewervanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestDocument1 pageYolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestAlan Gultia100% (1)

- Payments Threats and Fraud Trends Report - 2022 PDFDocument69 pagesPayments Threats and Fraud Trends Report - 2022 PDFSamuelPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Martin Funeral Homes Vs NLRCDocument9 pagesSt. Martin Funeral Homes Vs NLRClawdisciplePas encore d'évaluation

- Yupangco Cotton Mills vs. CADocument4 pagesYupangco Cotton Mills vs. CAvanessa_3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Fortress of Spears - Anthony RichesDocument817 pagesFortress of Spears - Anthony Richescamilush100% (4)

- Infiltrators!". The Police Then Pushed The Crowd and Used Tear Gas To Disperse ThemDocument3 pagesInfiltrators!". The Police Then Pushed The Crowd and Used Tear Gas To Disperse ThemAlfonso Miguel LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB vs. VelascoDocument8 pagesPNB vs. Velascovanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- CIR v Mirant Pagbilao Tax Credit RulingDocument1 pageCIR v Mirant Pagbilao Tax Credit RulingKate Garo83% (6)

- Standard Chartered Bank Employees Union vs. Standard Chartered BankDocument8 pagesStandard Chartered Bank Employees Union vs. Standard Chartered Bankvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Brotherhood Labor Unity vs. ZamoraDocument4 pagesBrotherhood Labor Unity vs. Zamoravanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Verceles Et Al vs. BLRDocument6 pagesVerceles Et Al vs. BLRvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- ICTSI Employees Dispute Daily Wage Computation MethodDocument6 pagesICTSI Employees Dispute Daily Wage Computation MethodCarmela SalcedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Alvarez vs. IACDocument11 pagesAlvarez vs. IACvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Golden Donuts vs. NLRCDocument14 pagesGolden Donuts vs. NLRCvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of the Philippines Supreme Court rules on attorney fees deductionDocument3 pagesRepublic of the Philippines Supreme Court rules on attorney fees deductionvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Laguna Metts Corporation vs. CADocument3 pagesLaguna Metts Corporation vs. CAvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vengco vs. TrajanoDocument3 pagesVengco vs. Trajanovanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on post-judgment compromiseDocument5 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court rules on post-judgment compromisevanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Samahan NG Mga Manggagawa Sa Hyatt - Nuwhrain-Apl vs. BacunganDocument3 pagesSamahan NG Mga Manggagawa Sa Hyatt - Nuwhrain-Apl vs. Bacunganvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- SC Rules on Backwage Computation and Reinstatement Order in Illegal Dismissal CaseDocument6 pagesSC Rules on Backwage Computation and Reinstatement Order in Illegal Dismissal Casevanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on union election disputeDocument8 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court rules on union election disputevanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Johnson & Johnson vs. Johnson Office and Sales UnionDocument4 pagesJohnson & Johnson vs. Johnson Office and Sales Unionvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Peralta vs. Director of PrisonsDocument52 pagesPeralta vs. Director of Prisonsvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- SC Orders Consolidation of Cases Against Former PCIC DirectorDocument3 pagesSC Orders Consolidation of Cases Against Former PCIC Directorvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on seaman's disability claimDocument3 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court rules on seaman's disability claimvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- T01C01 Laurel v. Misa 77 Phil 856Document27 pagesT01C01 Laurel v. Misa 77 Phil 856CJ MillenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center vs. NLRCDocument6 pagesSoutheast Asian Fisheries Development Center vs. NLRCvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- G & M (Phil) vs. RiveraDocument2 pagesG & M (Phil) vs. Riveravanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Supreme Court upholds dismissal of petition questioning voluntary arbitrator's decisionDocument3 pagesSupreme Court upholds dismissal of petition questioning voluntary arbitrator's decisionvanessa_3Pas encore d'évaluation

- SSS vs. CADocument21 pagesSSS vs. CAvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shipside Inc. vs. CADocument13 pagesShipside Inc. vs. CAvanessa3333333Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Collector of Internal Revenue Vs Rueda 42 SCRA 23Document4 pages1 Collector of Internal Revenue Vs Rueda 42 SCRA 23uhynu78Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iranian man sues DEA agentDocument12 pagesIranian man sues DEA agentEumell Alexis PalePas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Alonzo Robinson, 4th Cir. (1999)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Alonzo Robinson, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- BPI Vs Guevara DigestDocument47 pagesBPI Vs Guevara DigestRob ClosasPas encore d'évaluation

- Blaw Asm 3Document9 pagesBlaw Asm 3Anthony NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Going Back To FrancisDocument20 pagesGoing Back To FrancisLee SuarezPas encore d'évaluation

- Kenya Childrens Act No 8 of 2001Document193 pagesKenya Childrens Act No 8 of 2001Mark Omuga100% (1)

- Silence The Court Is in Session by Vijay Tendulkar 39Document14 pagesSilence The Court Is in Session by Vijay Tendulkar 39Chaitanya Shekhar 7110% (1)

- US Quest for EmpireDocument5 pagesUS Quest for EmpireCarol LeePas encore d'évaluation

- United States v. Frank Giampa, 758 F.2d 928, 3rd Cir. (1985)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Frank Giampa, 758 F.2d 928, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act 1992 Changed Grassroots DemocracyDocument3 pages73rd Constitutional Amendment Act 1992 Changed Grassroots DemocracynehaPas encore d'évaluation

- Green-Water NavyDocument6 pagesGreen-Water NavyDearsaPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay - The Downfall of The Iroquois ConfederacyDocument2 pagesEssay - The Downfall of The Iroquois ConfederacyAsep Mundzir100% (1)

- ComplaintDocument2 pagesComplaintKichelle May N. BallucanagPas encore d'évaluation

- Ace Punt FormationDocument2 pagesAce Punt FormationMichael Schearer100% (1)

- Verb Lists: Infinitives and GerundsDocument2 pagesVerb Lists: Infinitives and GerundsMarius RanusasPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure CasesDocument10 pagesCivil Procedure CasesRam BeePas encore d'évaluation

- Batches of Mismatches Regarding LachesDocument34 pagesBatches of Mismatches Regarding Lacheselassaadkhalil_80479Pas encore d'évaluation

- Carter TimelineDocument1 pageCarter Timelinehoneyl5395Pas encore d'évaluation

- When He Texts After Ghosting, Do Not ReplyDocument2 pagesWhen He Texts After Ghosting, Do Not Replymaverick auburnPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are The Key Features of The US Political System?Document11 pagesWhat Are The Key Features of The US Political System?Yuvraj SainiPas encore d'évaluation