Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

176 The Making of Modern Japan

Transféré par

Charles MasonDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

176 The Making of Modern Japan

Transféré par

Charles MasonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

176

The Making of Modern Japan

that made use of ordinary vocabulary and great brevity. The poet Matsuo (1644 1694), born the second son of an impecunious samurai, grew Basho up on the fringes of the upper class without its benets or income. Friendship with one of superior rank helped him for a time; when that ended, he moved to Edo and took a minor position in the water department. In 1680 he moved ) tree to a modest cottage; a disciple planted an ornamental banana (basho outside his door; the house, and then its resident, became named for it, as . In Basho s early days there was lively debate he changed his name to Basho and competition among different schools of poetry. Together with his friends he relished the challenge of linked-verse (renga) competitions in which two and three line offerings were pieced together in a somewhat meandering but meaningful progression. Gradually he settled on the three-line segment, of ve, seven, and ve syllables, using it as a single statement. Within this extraordinarily brief compass, the polysyllabic Japanese language could do little more than sketch a scene and suggest an emotion. It was thus all the more frequently did, a Zen-like ash of universal remarkable to produce, as Basho signicance in the presence of the daily and the ordinary. Accompanying this was a striking simplicity of vocabulary and setting. The sound of a frog leaping into an old pond, the sight of a crow on a naked branch, or summers grasses on a legendary battleeld could provide the setting in which the reader or listeners emotions did the rest. Often there was a transference of the senses, as emotion was reinforced by sight and sound. began a series of ve journeys, each of which resulted in a In 1684 Basho poetic narrative. For months at a time he wandered through distant parts of Japan, describing the setting and producing compelling verses telling of his loneliness and dread or sadness and serenity. He moved on foot and on horseback and took no supplies. He accepted no students for pay, something that was commonly done, though he occasionally sold examples of his calligraphy. Nevertheless by now his fame preceded him. Everywhere he went he was welcomed by leading local residents who outdid themselves to honor their distinguished guest. Evenings were usually devoted to the exchange of verses as the s. One locals did their best to match their more modest skills against Basho might have expected this in an urban, middle- or upper-class setting; that it took place in remote mountain villages tells a great deal about the accomplishments of the local elite and channels of information. s is Poetry has always held a central place in Japanese culture, and Basho of course one chapter in a great tradition. He himself expressed it well in a , famous passage; one and the same thing runs through the waka of Saigyo gi, the paintings of Sesshu , the tea ceremony of Rikyu . What the renga of So is common to all these arts is that they follow nature and make a friend of

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Basho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesD'EverandBasho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (18)

- Basho The Complete Haiku IntegralaDocument492 pagesBasho The Complete Haiku IntegralaShubhadip AichPas encore d'évaluation

- Matsuo BashoDocument5 pagesMatsuo BashoMaria Angela ViceralPas encore d'évaluation

- Haiku: History of The Haiku FormDocument8 pagesHaiku: History of The Haiku FormKim HyunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature of JapanDocument6 pagesLiterature of Japanmaria yvonne camilotesPas encore d'évaluation

- On Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk LucienDocument81 pagesOn Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk Luciencalisto.aravena.zPas encore d'évaluation

- (Japan) BashoDocument4 pages(Japan) BashoEhrykuh MaePas encore d'évaluation

- The Main Theme of BashoDocument4 pagesThe Main Theme of BashoANGELA V. BALELAPas encore d'évaluation

- Beginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)D'EverandBeginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuD'EverandCats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuPas encore d'évaluation

- Was A Common Sight in Japan To See Circulating Libraries Carried From House To House On The Backs of MenDocument8 pagesWas A Common Sight in Japan To See Circulating Libraries Carried From House To House On The Backs of MenZnoe ScapePas encore d'évaluation

- None Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoDocument11 pagesNone Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoRidhwan 'ewan' RoslanPas encore d'évaluation

- HAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaDocument16 pagesHAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaJoshua Lander Soquita Cadayona100% (1)

- Biographical Sketch - Matsuo BashoDocument4 pagesBiographical Sketch - Matsuo Bashoapi-544796190Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceDocument1 pageBashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceAraPas encore d'évaluation

- Matsuo Bashō - WikipediaDocument38 pagesMatsuo Bashō - Wikipediagolden wingsPas encore d'évaluation

- BOOK REVIEWS - The Japan Foundation NewsletterDocument16 pagesBOOK REVIEWS - The Japan Foundation NewsletterFredrik MarkgrenPas encore d'évaluation

- David Landis Barnhill, Bashos JourneyDocument211 pagesDavid Landis Barnhill, Bashos Journey2radial50% (4)

- Basho's HaikusDocument5 pagesBasho's HaikusSaluibTanMelPas encore d'évaluation

- HaikuDocument16 pagesHaikuMaria Kristina EvoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative AnalysisDocument8 pagesComparative AnalysisJoshua Pascua GapasinPas encore d'évaluation

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledBill BensonPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese Haiku by Peter BeilensonDocument66 pagesJapanese Haiku by Peter Beilensonrf880% (1)

- Basho HaikuDocument3 pagesBasho HaikusatoriasPas encore d'évaluation

- HaikuDocument7 pagesHaikuRafael Luis SoPas encore d'évaluation

- Show Appreciation For Songs, Poems, Plays, EtcDocument8 pagesShow Appreciation For Songs, Poems, Plays, EtcShawn MikePas encore d'évaluation

- 178 The Making of Modern Japan: Ukiyo-E Prints. Virtuoso Printmakers Illustrated The Ukiyo Zo Shi, As This GenreDocument1 page178 The Making of Modern Japan: Ukiyo-E Prints. Virtuoso Printmakers Illustrated The Ukiyo Zo Shi, As This GenreCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- The Old Pond by Matsuo BashoDocument8 pagesThe Old Pond by Matsuo Bashoemerine casonPas encore d'évaluation

- MatsuoipediaDocument21 pagesMatsuoipediaBalayya PattapuPas encore d'évaluation

- HaikuDocument25 pagesHaikuKim HyunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Poems - HaikuDocument2 pagesPoems - HaikuMabel BaybayonPas encore d'évaluation

- Basho 2Document15 pagesBasho 2coilPas encore d'évaluation

- Japanese Prints: 'Of long nights with orange lanterns''D'EverandJapanese Prints: 'Of long nights with orange lanterns''Pas encore d'évaluation

- One Hundred Poems From The Japanese: IntroductionDocument7 pagesOne Hundred Poems From The Japanese: IntroductionSergio Enrique Inostroza ValenzuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Delphi Collected Works of Basho and the Haikuists (Illustrated)D'EverandDelphi Collected Works of Basho and the Haikuists (Illustrated)Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Year of My Life, Second Edition: A Translation of Issa's Oraga HaruD'EverandThe Year of My Life, Second Edition: A Translation of Issa's Oraga HaruÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (1)

- Afro-Asian Literature (Final)Document4 pagesAfro-Asian Literature (Final)RU ELPas encore d'évaluation

- Daniel Crump Buchanan - One Hundred Famous Haiku - Japan Publications, US (1976)Document60 pagesDaniel Crump Buchanan - One Hundred Famous Haiku - Japan Publications, US (1976)pajaree.kanjanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Basho - Tlge Narrow Road To The Deep North and Other T? Travel SketchesDocument178 pagesBasho - Tlge Narrow Road To The Deep North and Other T? Travel SketchesKiruba Nidhi100% (2)

- Japan Haiku Poets: and SelectedDocument27 pagesJapan Haiku Poets: and SelectedClaire Jacynth FloroPas encore d'évaluation

- HaikuDocument12 pagesHaikuAlphanso BarnesPas encore d'évaluation

- Peipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoDocument8 pagesPeipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoHaiku NewsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Story of The Aged MotherDocument6 pagesThe Story of The Aged MotherOrdnajela Onaicul75% (4)

- Matsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESDocument3 pagesMatsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESshanid.saudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Classic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersD'EverandClassic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (4)

- On The Road AgainDocument3 pagesOn The Road Againfcrocco100% (2)

- Lowell Georgia Placido G-8 Sampaguita A Brief History of HaikuDocument2 pagesLowell Georgia Placido G-8 Sampaguita A Brief History of HaikuLara Mae B. PlacidoPas encore d'évaluation

- l3 21st Century PPDocument15 pagesl3 21st Century PPRic SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Haiku: Japanese LiteratureDocument14 pagesHaiku: Japanese LiteratureNestle Anne Tampos - TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- DGL, LunberryCMS2019LDocument14 pagesDGL, LunberryCMS2019LcoilPas encore d'évaluation

- The Haiku Masters:: Four Poetic DiariesDocument156 pagesThe Haiku Masters:: Four Poetic DiariesdanieldelosriosPas encore d'évaluation

- Different Forms of PoetryDocument13 pagesDifferent Forms of Poetrykhryslerbongbonga30Pas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoDocument7 pagesAnalysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoMervyn Larrier100% (11)

- I Wait for the Moon: 100 Haiku of Momoko KurodaD'EverandI Wait for the Moon: 100 Haiku of Momoko KurodaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Kobayshi IssaDocument6 pagesKobayshi Issaapi-518643296Pas encore d'évaluation

- Composting: Composting Turns Household Wastes Into Valuable Fertilizer and Soil Organic Matter. in Your GardenDocument6 pagesComposting: Composting Turns Household Wastes Into Valuable Fertilizer and Soil Organic Matter. in Your GardenCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Phone Idect C10i User GuideDocument47 pagesPhone Idect C10i User GuideCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ignoring Alternative ExplanationsDocument1 pageIgnoring Alternative ExplanationsCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- $10,000 Key To Influence:: Overcoming Resistance With Omega StrategiesDocument1 page$10,000 Key To Influence:: Overcoming Resistance With Omega StrategiesCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Conscious Reaction) and Focus On Anticipated Regret (Which Is Conscious andDocument1 pageConscious Reaction) and Focus On Anticipated Regret (Which Is Conscious andCharles MasonPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3: English and European Literature LESSON 1: Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare Lesson OutcomesDocument12 pagesChapter 3: English and European Literature LESSON 1: Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare Lesson OutcomesMariel C. Bombita57% (7)

- Mamá Raton y Sus HijitosDocument1 pageMamá Raton y Sus HijitosOlivia CanelaPas encore d'évaluation

- MM 47 03 2017Document76 pagesMM 47 03 2017Adolf Bormann100% (1)

- IFP II SyllabusDocument7 pagesIFP II SyllabusJustin OhPas encore d'évaluation

- The Films of Woody AllenDocument213 pagesThe Films of Woody AllenAnonymous lcIhVy8npc100% (7)

- Capstone Assignment Ecd 470Document8 pagesCapstone Assignment Ecd 470api-341533986Pas encore d'évaluation

- Asking Students What Philosophers TeachDocument19 pagesAsking Students What Philosophers TeachmenosfaldaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sidharth 2020ENG1009 DSE European RealismDocument9 pagesSidharth 2020ENG1009 DSE European RealismSidharth RatheePas encore d'évaluation

- Miss Brill Katherine Mansfield ThesisDocument8 pagesMiss Brill Katherine Mansfield Thesiskimberlygomezgrandrapids100% (2)

- Qin Xiang English 342 DweDocument18 pagesQin Xiang English 342 DweDaniel Alejandro Saez100% (12)

- Gift WrappingDocument17 pagesGift WrappingDiana de castroPas encore d'évaluation

- Tell Edfu 2009-2010 Annual ReportDocument11 pagesTell Edfu 2009-2010 Annual Reportalanmoore2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- TLE-Sep 7-8Document2 pagesTLE-Sep 7-8Ladyjobel Busa-RuedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Rubrics DemoDocument9 pagesRubrics DemoLederly JosePas encore d'évaluation

- Dissertation Sur Madame Bovary de FlaubertDocument8 pagesDissertation Sur Madame Bovary de FlaubertBestPaperWritingServiceReviewsToledo100% (1)

- Rembrandt 1606 1669 The Mystery of The RevealedDocument104 pagesRembrandt 1606 1669 The Mystery of The RevealedMAGIC ZONEPas encore d'évaluation

- The Birds - Mochila Bag Pattern v3Document12 pagesThe Birds - Mochila Bag Pattern v3cherielyn.rivera100% (1)

- Yarn - Issue 65, March 2022Document60 pagesYarn - Issue 65, March 2022Natalia AstudilloPas encore d'évaluation

- CoveringDocument58 pagesCoveringAndy SetiawanPas encore d'évaluation

- 04-Point of View Day 2Document4 pages04-Point of View Day 2Joni PrussiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Art Appreciation-Chapter 1.4 - Assumptions of ArtDocument2 pagesArt Appreciation-Chapter 1.4 - Assumptions of ArtVanessa SorianoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ucla Athletics For Print and Digital Applications: Style GuideDocument61 pagesUcla Athletics For Print and Digital Applications: Style GuideElimarketPas encore d'évaluation

- Club Report Final-1Document21 pagesClub Report Final-1rakshansh jainPas encore d'évaluation

- Field Report T-901Document1 pageField Report T-901Tahir Iqbal. Kharpa RehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Paul Gilreath - The Guide To MIDI OrchestrationDocument716 pagesPaul Gilreath - The Guide To MIDI OrchestrationTomás Cabado98% (52)

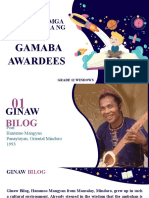

- Gawad Sa Mga Manlilikha NG BayanDocument65 pagesGawad Sa Mga Manlilikha NG BayansamPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuklip: 38Mm Casement Window Technical CatalogueDocument27 pagesNuklip: 38Mm Casement Window Technical CatalogueEvans Mandinyanya100% (1)

- Pier Paolo TamburelliDocument9 pagesPier Paolo TamburellijsrPas encore d'évaluation

- Members List WCCI SouthDocument6 pagesMembers List WCCI Southaptech32smilesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebook - PMP - Verbal Aikido - Luke Archer - enDocument136 pagesEbook - PMP - Verbal Aikido - Luke Archer - enGuillaumea Foucault100% (1)