Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Beyond The Archive of Silence

Transféré par

Liza RTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Beyond The Archive of Silence

Transféré par

Liza RDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

HISTORY ON THE LINE Beyond the Archive of Silence: Narratives of Violence of the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh by Yasmin

Saikia

In 1971 two wars broke out in East Pakistan. One was a civil war fought between West and East Pakistan, and the other an international war fought between West Pakistan and India. In the wars ethnicity colluded with national interests and state politics, and the armies of West Pakistan and India became involved in violence, mainly targeted against the civilian population of East Pakistan, particularly women. Both the Pakistan and Indian armies were occupying forces and were assisted in their activities by local supporters. The Bihari community (Muslim Urdu speakers and recent migrants to East Pakistan from India after the partition in 1947) supported the West Pakistan army in the hope of saving a united Pakistan. A sizeable number of Bengalis, members of the Muslim League, the political organization that had conceived and created Pakistan, also supported the West Pakistan army. The Indian army, by and large, was supported by the nationalist Bengalis of East Pakistan, both Muslims and Hindus. With the help of the Indian government, the Bengalis created a local militia called the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army). The combined forces of the Indian army and Mukti Bahini defeated the West Pakistan army and forced them to surrender. At the end of the civil war the Pakistan government lost legitimacy in its eastern province; the international war resulted in the partitioning of Pakistan and creation of an independent nation-state of Bangladesh. The two wars of 1971 are generally referred to by a single name: the Liberation War of Bangladesh. The current historiography on the Liberation War is focused solely on the investigation and discussion of conicts between the armies and militias of West Pakistan, East Pakistan, and India, and the external contexts of battles between the different ethnic groups of Bengalis, Biharis, and Pakistanis.1 The inner conicts within the communities that led to rampant violence against women in the wars are overlooked and womens voices are actively silenced. As a result womens experiences and memories of the war are rendered invisible in the ofcial history of 1971. To overcome the silences concerning gendered violence and to document a peoples history of 1971, I have undertaken to reconstruct through oral history, eldwork, and archival research the experiences of survivors men and women in

History Workshop Journal Issue 58 History Workshop Journal 2004

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

276

History Workshop Journal

Courtesy of the Liberation War Museum.

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

Fig. 1. Protest poster showing family brutalized and killed in 1971.

Fig. 2. Salina Parveen, journalist, abducted and killed in 1971.

Courtesy of the Liberation War Museum.

History on the Line

277

Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India who participated in, experienced, and witnessed the Liberation War. My aim is to probe into the moments of violence, the victimization of women, the actions and experiences of men, and the trauma produced as a consequence. Through this exploration of personal and collective memories, I hope to demonstrate the linked, though conicting, experiences of suffering of people in the subcontinent and to construct a story of survivors of the Liberation War. This research is also an attempt to rethink communal and state violence in postcolonial South Asia and arrive at a clearer understanding of the legacies of the partitions of 1947 and 1971. ENCOUNTERING THE ELUSIVE ARCHIVE

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

A summer research grant enabled me to travel to Bangladesh in 1999 and launch a pilot study on womens experiences during the Liberation War, as well as their later memories. During this initial visit to Bangladesh, I found that nothing was recorded about women in the traditional sites for historical research in archives and libraries. In the media, however, I heard the shrill voices of politicians invoking the violence of 1971 and demanding redress. In this political-public discourse every man from Pakistan was reduced to the generic label of perpetrator and every Bangladeshi man became a mukti judha, a war hero. In this national political memorializing, women were tellingly absent, even though a count of 200,000 rape victims was used by politicians to mobilize anger against Pakistani enemies several decades later. Such narratives created and clearly demarcated societies evil Pakistan and good Bangladesh. No possibilities existed for blurring the boundaries and generating a dialogue between the two. My initial investigation of this narrative in newspapers made it evident that government ofcials, scholars, and political and religious leaders all restricted womens speech. There was a denite unwillingness to ask difcult questions that could potentially expose and force people to come to terms with the reality of a horric past in which Bengali men participated, along with Pakistani and Bihari men, in brutalizing women. The silence was all pervading. The question that arose for me was how could one move beyond such institutional silence and recover womens voices? I was convinced that survivors could tell their experiences if they were allowed to do so. Determined to overcome the silence of the state archives, I returned to Bangladesh in 2001 and lived there for a year. I embarked on a multi-sited and multidisciplinary project, combining oral history with literary, audiovisual, and newspaper research. I started my research in the Dhaka National Library and Archive reviewing local and national dailies from 1971 and 1972 to investigate how they represented violence against women. The newspaper reports did not give womens stories, but allowed me to trace the path of soldiers and map their camp sites. I had become aware through reading Bengali novels that these were places where women were

278

History Workshop Journal

held in captivity for sexual slavery during the war.2 In addition, the audio recordings about womens experiences available at the Dhaka Radio Station, relating mainly to the loss of family members, and the visual materials and family documents in the Liberation War Museum, enabled me to develop an outline of the kind of violence that women experienced and the strategies later adopted to organize a silence about them, evident across a range of the nations public institutions. Armed with this initial research and documentation, I began my oral history project with the aim of correcting the imbalance and placing womens suppressed memories in the narratives on 1971. Many social activists and womens rights advocates discouraged me from the project. They warned me that women will not speak and insisted that I was wasting my time trying to nd women who would bear witness to the crimes of 1971. They actively discouraged me from including Bihari women, the enemies of Bengalis, in my research project. Undeterred, I went to Camp Geneva in Dhaka, a forbidden space for most Bengalis in Bangladesh, where Bihari refugees have been living since the end of the war, for over three decades, as stateless people. After some initial hesitation and reluctance, many women came forward to assist me in locating witnesses and victims of 1971, as well as some of the children who had suffered violence. Conversations with the survivors conrmed that women had been subject to extreme violence. Some of them shared with me their tightly-guarded secrets and asked me to ensure that their stories gained international attention. These initial encounters in Camp Geneva led me to many more Bihari refugee camps across Bangladesh where I heard and recorded testimonies that established the widespread brutality against women during the war. I interviewed both Bihari and Bengali victims, initially aided by a cultural organization the members of which included a variety of professionals and activists who used street plays and political dramas to document a public history of 1971 in northern Bangladesh. The young women I met through this organization led me to women who were brutalized in the war. In turn, these women led me to many more victims, and I travelled all across Bangladesh meeting survivors of 1971. Being an outsider in Bangladesh but uent in Bengali and Urdu privileged me to speak to, and to build trust with, anguished Bengali and Bihari women, who were extremely critical of their own community and society. It became clear to me that 1971 was truly what one woman, Sakeena Begum, a Bihari victim, described as the year of anarchy and end of humanity in Bangladesh.3 I recorded around fty testimonies and corroborated these accounts with over two-hundred Bengali and Bihari witnesses. From these women, who were of varied ethnic, class, religious and social backgrounds, I learned that housewives, school and college students, professional women and sex-workers were victims of violence. Their ages ranged from twelve to fty-seven. From the beginning I was concerned about the ethics of the research I was

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

History on the Line

279

pursuing. I was troubled whether my probing into womens memories would instigate more violence against them. The women who shared their stories of pain and suffering with me, however, did so expecting that I would represent their experiences to others and so help them to overcome the silence that had been imposed on them, even after liberation, both by men and by the state. Many said that to have a voice and to have their pain recognized would be justice done, even if it were many years after the event. They were angry that the state had not recognized their sacrices, and had silenced the issue of gender violence rather than undertaking an investigation. Most of them were bitter that not even a plaque or memorial was dedicated to women victims. Nonetheless, I remained concerned about the impact on these women of a public historical interpretation of their lives and memories. There were times when I seriously doubted whether it would be positive. For instance in one of my eld trips to northern Bangladesh, I met a schoolteacher who at our very rst meeting indicated to me that she wanted to tell her story. She invited me to her home, but after a meal when we sat down to talk, three other women from the village stopped by to chat and stalled the conversation. Although discouraged, on her insistence I went back to her home the next day hoping to listen to her story. But that day the crowd waiting for me was larger, comprising a mixed group of men and women. The men recounted to me exaggerated stories about their brave feats in 1971. The women were silenced. The third day when I went back to her house, a huge crowd of men barred my entry demanding why I was repeatedly coming back to speak to the schoolteacher. What is your interest in her?, they demanded. They threatened me, making it clear that they did not want me to return. Weeks later, I received a letter from my friend, the teacher, that detailed a story of starvation, brutality and rape by a Bengali neighbour in 1971. She said: I was only thirteen years old then, and this elderly neighbour whom my family had requested to help me get safe passage out of the camp (where we were kept in Pakistani custody) destroyed me. She forbade me from using her name in my research and the details recounted in the letter. Her story, and her fears, were far from unique. During my fteen months of research in Bangladesh there were several instances when I seriously doubted the effects my research would have. The larger truth however is more encouraging. By and large, the project had a benecial impact on the women themselves. Almost all of the women I interviewed conded that sharing their traumatic experiences was therapeutic because someone had cared to listen to them. This shattered the myth that women did not want to talk. On the contrary, they said that my willingness to listen and the opportunity I had provided them to reect on their memories and make sense of them were invaluable. At another level, too, my research had an impact. My two research assistants, a Bengali man and a woman, both of the post 1971 generation, discovered an aspect of their history unknown to them. They became enthusiastic about taking the work a step further and organizing young men and women at the university

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

280

History Workshop Journal

to begin a dialogue with Bihari and Bengali women in order to overcome the barriers of distrust and hate that have kept them apart. Their drive to revisit a historical chapter and to democratize it in order to produce a new community was inspiring. I hope they have accomplished some of their objectives. Another question that bothered me was how much I could depend on peoples narratives to construct a reliable picture of what happened in 1971. Recent scholarship has made us aware that memory is slippery and selective.4 From the beginning, I remained vigilant with regard to survivors narratives. But I also realized that three decades of silencing have more or less isolated the victims, pushing them to the extreme margins of society, and have made a coherent narrative of their memories of violence almost impossible. So when some of them tried to recall for me their experiences of violence they could do so only in disjointed fragmentary sentences. On many occasions even this was not possible. Mumtaz Begum, a survivor, told me, I dont remember anything, but I am still in pain. When I inquired further about the nature and cause of her pain, she said, My body is in pain, but I cant tell you what they did to me. I was unconscious throughout my captivity (which lasted eleven days). I was seven months pregnant when they took me to the camp.5 Her captors, it appeared, were both Bengali and Pakistani men. Although the memories of survivors are somewhat foggy and language is not always sufcient, I believe like Arthur Klienman,6 Veena Das,7 Susan Brison8 and many others that personal suffering can and should be made social. Without it, extreme experiences of individual suffering will become unthinkable and therefore unknowable. Scholarly obsession with impersonal and rigorous demands for substantiating individual experience with corroborating evidence bring the danger of muzzling, rather than empowering, the voices of women in Bangladesh. I was aware of the shortcomings of personal memory, but keen to hear what the women had to say. I approached them for information in order to transform memory into language and destroy silence by talking about it. Along with listening to the narratives of survivors, whenever possible, I tried to probe into other sources, including government documents, hospital records, social service and rehabilitation reports, photographs and visual media. The supplementary materials, whenever available, corroborated womens testimonies and lled in many gaps. Over time, these documentary materials and testimonies helped me develop a clearer picture of what happened in 1971. A question that continued to bother me was: how do I nd a language to communicate the horrors of 1971? I have been grappling for a language to convey what Inga Clandinnen calls catastrophetales.9 Listening to such tales, as many know, imposes a responsibility. We are obliged to tell the stories of survivors, for these are the entry point to understand what happened. Along with telling, it is absolutely necessary that we learn to listen to what the people, the survivors, are saying. Only then we can come up with a language to report what we know.

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

History on the Line

281

The task of telling what happened in 1971 is daunting because there are no laid-out paths to follow; every telling invariably betrays the original voice and disrupts the silence that has been kept intact for over three decades. Nonetheless, following Hayden Whites urging to make the historian a middle voice, I have decided to insert my voice in the unveiling of the horrors of gendered violence in 1971.10 For me, this has become more than a historical research project. My role has changed during the course of the research from that of a chronicler to an advocate. I now see myself as a storyteller with a mission. My aim is to make this research a means of bearing witness to the violence of 1971, and of raising awareness about the spurious currency of normality in postcolonial South Asia. Bearing witness to the crime committed against women in 1971 is an aggressive, iconoclastic act. It is an attempt to write a counter history and a way to shake the foundations of the history that exists in the subcontinent today. But I am not a lone voice in demanding a new excavation of postcolonial violence. Kamla Bhasin and Ritu Menon11 and Urvashi Butalia12 pioneered the project of researching and writing alternative narratives of partition violence in 1947. They forged a path for other scholars wishing to expand the boundaries of feminist history in South Asia and to undertake research on the second partition of the subcontinent, in 1971. Like them, my goal is to emphasize the possibility of alternative retellings of the events and history of violence and to demand change. The rich feminist literature on 1947 and my direct encounter with survivors of 1971 have helped me to understand one issue. It is not the women themselves, but the structures and institutions outside their control, that restrict their speech and force them to forget what they endured. Silence serves as a tool to confuse women, and even now, decades later, the women cannot make sense of their horric experiences nor nd answers about why they were targeted in the war that men fought and controlled. The story of Madhumita (name changed) that I quote below illuminates womens experiences during and after the war. Madhumita told me her story in many parts; I quote only two segments of a larger interview that was over six hours long. In her story we hear the voice of a young Bengali Hindu girl who was brutalized and tormented by her neighbours and family friends, who used the occasion of the war to victimize her. We learn from her that after the war her life did not take a better turn, but rather that she was made to pay dearly for her victimization in 1971. Madhumita was, and continues to be, a victim of her own society; the oppression is unending. I met Madhumita in her home. Her elderly mother (around eighty years old) was also present at the rst meeting. Madhumita started her story by introducing herself and her family. I (Madhumita) was fteen years old and a student of grade VIII in 1971. Ours was a rich Hindu merchant family and we lived in a composite Bengali village. On June 21, 1971, local Bengali and Bihari men of the

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

282

History Workshop Journal

Muslim League, supporters of Pakistan, came to our house. My family used to know them very well. They came to arrest my father and brothers because our family was involved in the liberation struggle and were supporters of the Mukti Bahini. But when the Biharis approached our house, all the adult men ed. My youngest brother, who was eleven years old, could not escape. I tried to help him, but was apprehended by the attackers. They locked me in a room; my brother was there too. At this point of the interview, her mother, who was sitting besides her, broke down and started to wail. Madhumita stopped recounting the details about the horrible night of her victimization. Her mothers wail penetrated the stillness of the room. Her cries were heartrending. I had destroyed whatever peace had existed in the household, and that shook me. But I could not leave. So I sat there and listened to the painful screams of her mothers agony. The pain of remembering what happened on the fateful night was unbearable for her. The old lady slumped and fainted. Then Madhumitas brother came in, and carried his mother out of the room. Our conversation stopped for the day. Several weeks later when I met Madhumita again and she began her narrative where she had left off. On this occasion her mother did not join us. Without making direct reference to her experience of sexual violence, Madhumita said, After they nished their business they set the house on re and walked away. But I could not let my brother die. So I dragged myself and despite the pain I was suffering, I helped my brother to escape by breaking open the door. I was badly burned in the process. That night, I hid in our backyard pond. Next morning, when I emerged from the pond chunks of esh started falling off my body. I had no clothes on, except burned shreds to cover some parts. When I looked around, I saw some men from our village returning from their morning prayers. On seeing me they made funny noises and gestures. I tried to tell them I was not a prostitute but so-and-sos daughter, and tried to solicit their help. But they walked away. Since that day I have been a living dead. My body is in pain. I have no status, job, or education. My brother now owns the family business and I live in his house. I gave up my dignity, my life, everything for my brother; but today I am no better than his servant. This is womens lot in Bangladesh.13 Madhumitas voice, like that of many Bangladeshi women, is the voice of a victim. Pride in saving her brother is intricately linked with her own victimization at the hands of her neighbours. In her story we hear that her familys religion and politics provided justication for making her the enemy body. Bengali and Bihari Muslim men under the guise of saving nation and community destroyed her and then left her to die and burn. We almost smell her burning esh, and can feel her pain as she emerges from

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

History on the Line

283

the pond to seek help from her neighbours only to be rebuffed and treated ever since as a social outcast. As we listen to her we want to undo the nightmare of that night and inject a measure of normality into her life. Instead, we are left with a sense of her unending loneliness, with no one to share her memories, fears, anxieties or hopes. I spoke with and recorded the testimonies of over fty victims in Bangladesh during my fteen months stay. Almost all the women who shared with me their horric memories of war talked at length about the pain of betrayal inicted by men they knew men who belonged, perhaps, to their community, their village, even their family. One Bihari woman recounted the murder of her daughter in 1971. [My] daughters name was Fatima. She was eighteen years old in 1971 and was married. She was expecting her rst child in a few months. After the war was over, on March 28, 1972, some Bengali men from [their] neighborhood stormed into [their] mohalla [compound]. They killed Fatimas husband, then they pulled her out of her room into the courtyard. They disrobed her. Then they slit her throat. But that was not enough. They ripped open her stomach, pulled out the unborn child and tore it into two. Fatima died immediately. Recounting this story was not an easy task for Fatimas mother. She lost her composure many times. But she continued. My daughter was innocent. Like all other women in Bangladesh she was like cattle. We are here because our men wanted us to be here. I came to this country because of my husband. He thought he would be better off in East Pakistan, so we came here in 1957 from India. I never chose to come here, nobody even asked me. No one asked my daughter what she wanted. The Bengalis thought she was an enemy because she spoke Urdu. They killed her without showing any mercy. It was not her crime that she was born a Bihari. Has anyone asked us women what we did to deserve this? Has anyone asked a mother how much it hurts to lose a daughter? I am a victim, and I understand what other victims feel. Women are victims in this country. Help us, please, help us. We also deserve to live like human beings.14 These testimonies of women shock us, as they should. 1971 was a nightmare; the violence was relentless. The enemy, as women revealed over and over again, was within, not outside. This is why women have been forced to remain silent.

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

284

History Workshop Journal

INTERROGATING ANOTHER SOURCE: THE PERPETRATORS Extended conversations with women made me realize that I had to talk to those men who made active choices to maintain womens silence. I wanted to encourage them to bear witness. Towards this end, I began collecting army reports and public records, and turned to oral history to collect personal testimonies of doctors, politicians, bureaucrats, veterans and civilians who had joined, supported and assisted in the independence of Bangladesh. The picture that emerged was complicated. They gave me a lot of information about political policies, such as the recruitment of Mukti Bahini soldiers in refugee camps located in India; the performance of mandatory abortion on pregnant women; the destruction of records and reports on womens rehabilitation programmes to maintain their honour; and the silencing of raped women through abandonment by their own families. From many decorated ofcers and women victims I learned about military camps, detention centres, public-works projects and similar ventures which the Pakistan army organized. These accounts portrayed women as the principal targets of male oppression and violence, both in the camps, and in towns where ghting war broke out between the Mukti Bahini and the Pakistan army. Soldiers of the Mukti Bahini proudly talked about their units, the discipline and regulations they were taught and lived by, the battles they fought in, and even about the kind of violence to which they subjected their enemies Pakistanis, Biharis, and those Bengalis who opposed the freedom struggle. The soldiers, however, rarely talked about their treatment of women, although many casually mentioned that they had joined the army not to save women, but their country. From men who served as wartime security guards at camps and business premises which were turned into detention centres for women, I learned about the brutalities inicted upon women. Many of these men are troubled that they did not do more to save women detainees, although some are married to women they rescued. From these accounts, it was easy to read that both action and ideology were carefully planned and upheld by the elite state actors who gloried gruesome violence as acts of valour and national pride. Perpetrators thus came in many forms. But sexual violence was not a random act in 1971. The state made these men freedom ghters and gave them power to carry out its will with violence, if need be. The rhetoric of war and perception of Pakistanis and Biharis as the enemy propelled Bengali men to commit horric acts, and vice versa, and these often metamorphosed into sexual violence against women in order to terrorize and force the whole communities into fear and submission. The violence that men indulged in during the war does not enable us to understand the history of the Liberation of Bangladesh. Rather, it makes us recoil; we want to run away from it. But can we keep running away from

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

History on the Line

285

this history of violence? Indeed it is a depressing knowledge that I am suggesting we search for. Yet, we are obliged to. If we listen to the voice of a perpetrator we will understand why we need to search, probe, and know. Biman (name changed) narrated this horric story to me. He said, On April 3, 1971, the Pakistan army came to our town. The Biharis in our railway colony were emboldened. We saw them walking around the place without fear and it made us very angry. I and ve other friends, who had joined the Mukti Bahini, decided to punish them. We went to one of our Bihari neighbours house. I used to call him uncle and his daughter was my sisters friend. She used to refer to me as brother. But that day all human ties were broken. We forcibly entered the house . . . grabbed the young girl and stripped her naked. She was struck with fear and shame. She ran out of the house and we ran after her. The crowd pursuing her grew in size. I had only one thought in my mind. I want to rape and destroy this girl. I want to destroy the Biharis, they are our enemies. . . . Abdul Hussain (a person I did not like) saw us chasing the girl. He came out of his house, wrapped the girl with a shawl and took her inside. He told the crowd, If you want to take this girl, take her over my dead body. We all stood there. No one had the courage to enter his house and drag her out. At that moment I realized I had become a criminal. The gun they had given me was a tool to kill. They had taught me how to kill. They made me cold like a snake. What have I become?, I thought. During the war, I committed many crimes . . . Nationalism is corrupting; I understand it only today.15 When I heard this confession from a perpetrator of violence, I was dumbfounded. I had not expected to hear such a story. Even as I listened, confusing and contradictory thoughts and feelings clashed in my mind. I found myself asking: What am I supposed to do? Should I tell him, as I had the victims, that I empathize with his suffering? Do I tell him he is a criminal and deserves the agony of his memory? Should my role as a researcher be predictable, to commiserate with the victims and loathe the perpetrators, even one such as Biman, whose pain, though denitely different from his victim, is deep and troubling. I was confused. Although I could not come up with a resolution to my own troubled thoughts, I understood then, as much as I do now, that what I heard was a voice from the grave, a man damned by his own memories and actions, a lonely, sad gure who cannot talk about his experiences in the war because he is not allowed to reveal and expose the criminal actions behind nation-building and nationalism. Worse still, his story has no place in a Bangladesh that revels in the glory of victory in 1971. Perpetrators were the Pakistani others, so the state tells people in Bangladesh. It is an easy, uncomplicated story, until we start investigating. Then the picture becomes convoluted, murky and muddy. Perpetrators appear in many forms and under many guises Pakistani,

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

286

History Workshop Journal

Bengali, Bihari. But there is a common element that binds them within a shared framework. Driven by the spirit of nationalism and nation-building, these men committed horric crimes that haunt them even today. Pakistani soldiers and their Bihari supporters raped and killed to save a nation; Bengali men also raped and killed in the hope of making a new nation, which they did. Who is guilty? What was the power that transformed ordinary men into criminals? I am not saying we should absolve the rapists and killers, but I am asking who is to blame? I have come to realize from listening to the stories of survivors that we need to move beyond the individual and investigate larger institutions such as the state and the ideology of nationalism that drove the war and used it to aggrandize power. To understand the process and creation of the sovereign power of the state that made citizens into agents for raping, killing, brutalizing, we have to listen to both victims and perpetrators.16 We would be fools not to listen to what they are saying, because in their stories is the evidence of what happened in the Liberation War, a story that has been suppressed. I plan to undertake the next segment of my research in Pakistan. My aim there will be to investigate not simply what soldiers and their supporters did in East Pakistan (Bangladesh), but what motivated them. How did the state make men obedient agents in order to carry out violence against their countrymen that seems to defy reason and confound our imagination? Did Pakistani soldiers see their victims as people or as detestable Hindus/Bengalis? Was gender violence a result of a temporary failure of control of individual passion, or was it a male madness which was carefully cultivated, orchestrated, and unleashed? My goal is to investigate and understand the construction by the state of an ideology of masculine power, and the cultivation of ethnic and religious hatred which were used systematically by different groups during the war. One may ask why should we tell the pain of victims alongside the troubled memories of the perpetrators? How can one be an advocate for victims and give voice to perpetrators too? Bearing witness to 1971 involves a kind of intimacy and distancing with people, events, and outcomes. One has to locate oneself between two poles one of understanding and the other the refusal to understand so that we recognize we are all part of it, yet do not become that which we loathe. I have decided to investigate and give voice to the memories of perpetrators not in order to exonerate or befriend them, but to examine and represent the belief that the perpetrators in our midst can teach us something about ourselves, and about the possibilities and limits of being human. If people are cultivated to become perpetrators of violence, and if their ensuing actions affect us, then should we not examine the interdependence of all humans? Should we not expose those sites of power where violent strategies are conceived that validate killing, raping, and brutalizing one human by another human? A close look at the perpetrators of 1971 is essential to develop an ethico-political thinking about violence in postcolonial South Asia.17

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

History on the Line

NOTES AND REFERENCES

287

1 Anthony Mascarenes, The Rape of Bangladesh, Vikas, New Delhi, 1971; S. Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1977; G.W. Choudhury, The Last Days of United Pakistan, Hurst and Company, London, 1975; I. Cohen, The Pakistan Army, California University Press, Berkeley, 1984; R. Sisson and L. E. Rose, War and Secession: Pakistan, India and the Creation of Bangladesh, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1990. 2 Nilima Ibrahim, Ami Birangana Bolchi, Jagrati Prakashan, Dhaka, 1998; Rabiya Khatun, Ekattorer Noymas, Agamee Prakashani, Dhaka, 1991; Raqul Islam, Narihatya O Narinirjatane Kancha, Ananya, Dhaka, 1994. 3 Personal interview, 20 February 2001, Syedpur, Bangladesh. 4 Pierre Nora, Between Memory and History: Les lieux de mmoire, transl. Mark Roudebush, Representations 26, 1989, pp. 725; J. Fentress and Chris Wickham, Social Memory, Blackwell, Oxford, 1992; Jacques Le Goff, History and Memory, transl. Rendall Steven and Elizabeth Claman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1992; M. Matsuda, The Memory of the Modern, Oxford University Press, New York, 1996. 5 Personal interview, 10 February 2001, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 6 Arthur Klienman (ed.), Social Suffering, Cambridge, Academy of the Arts and Sciences, 1996. 7 Veena Das, Crisis and Representation: Rumor and the Circulation of Hate, in Disturbing Remains: Memory, History and Crisis in the Twentieth Century, ed. M. Roth and C. Salas, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2001. 8 Susan Brison, Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of Self, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2002. 9 Igna Clendinnen, Reading the Holocaust, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999. 10 Hayden White, Historical Emplotment and the Problem of Truth, in Probing the Limits of Representation, ed. S. Friedlander, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1992. 11 Kamla Bhasin and Ritu Menon, Borders and Boundaries: Women in Indias Partition, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, 1998. 12 Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence, Duke University Press, Durham NC, 2000. 13 Personal interview, 10 April and 24 October 2001, Chittagong, Bangladesh. 14 Personal interview, 9 November 2001, Khulna, Bangladesh. 15 Personal interview, 16 November 2001, Chittagong, Bangladesh. 16 G. Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, transl. D. Heller-Roazen, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1998; G. Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: the Witness and the Archive, Zone Books, New York, 1999. 17 Hannah Arendt, Understanding and Politics, Partisan Review 20: 4, 1953, pp. 37792; Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, Viking Press, New York, 1965; Hannah Arendt, On the Nature of Totalitarianism: an Essay in Understanding (1953), in her Essays in Understanding, ed. J. Kohn, New York, Harcourt Brace, 1994.

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org by guest on February 7, 2011

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Torah SecretsDocument4 pagesTorah SecretsAchma2016100% (2)

- What Is Reformed Theology Study GuideDocument32 pagesWhat Is Reformed Theology Study Guiderightwingcarpenter5990100% (2)

- Radharani WorkbookDocument24 pagesRadharani WorkbookSuePas encore d'évaluation

- Fusion Reiki Manual by Sherry Andrea PDFDocument6 pagesFusion Reiki Manual by Sherry Andrea PDFKamlesh Mehta100% (1)

- Commentary On Parting From The Four AttachmentsDocument18 pagesCommentary On Parting From The Four AttachmentsAlenka JovanovskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Marx, On ColonialismDocument392 pagesMarx, On ColonialismLiza R100% (5)

- 10 - Chapter 5 PDFDocument30 pages10 - Chapter 5 PDFGiyasul IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Althusser-Essays in Self CriticismDocument141 pagesAlthusser-Essays in Self CriticismLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Wait As Eagles EbookDocument198 pagesWait As Eagles EbookTINTIN RAIT100% (9)

- Unsettling Partition Jill DidurDocument212 pagesUnsettling Partition Jill Diduralifblog.orgPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of violence faced by women during the partition of India as depicted in Urvashi Butalia's The Other Side of SilenceDocument8 pagesAnalysis of violence faced by women during the partition of India as depicted in Urvashi Butalia's The Other Side of SilenceRohan Singh100% (1)

- Labor Relation Case DigestsDocument48 pagesLabor Relation Case DigestsArahbellsPas encore d'évaluation

- Six Things to ConsiderDocument102 pagesSix Things to ConsiderMurg Megamus50% (2)

- The Spectral Wound by Nayanika MookherjeeDocument51 pagesThe Spectral Wound by Nayanika MookherjeeDuke University Press50% (2)

- Quit India Movement Demanded End to British RuleDocument12 pagesQuit India Movement Demanded End to British RuleAziz0346100% (1)

- A Treatise On Meditation by LediDocument239 pagesA Treatise On Meditation by LediClaimDestinyPas encore d'évaluation

- History of QuranDocument71 pagesHistory of Quranarifudin_achmad100% (1)

- Edred Thorsson - The Soul (1989)Document2 pagesEdred Thorsson - The Soul (1989)Various TingsPas encore d'évaluation

- Magnus Marsden - Mullahs, Migrants and MuridsDocument25 pagesMagnus Marsden - Mullahs, Migrants and MuridsLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- The Land of Two Partitions and BeyondDocument246 pagesThe Land of Two Partitions and Beyondbilalmpdd100% (3)

- Unclaimed Harvest: An Oral History of the Tebhaga Women's MovementD'EverandUnclaimed Harvest: An Oral History of the Tebhaga Women's MovementPas encore d'évaluation

- War Heroines Speak: The Rape of Bangladeshi women in 1971 war of IndependenceD'EverandWar Heroines Speak: The Rape of Bangladeshi women in 1971 war of IndependenceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Marx and EcologyDocument306 pagesMarx and EcologyLiza R100% (1)

- History On The Line Beyond The Archive of Silence: Narratives of Violence of The 1971 Liberation War of BangladeshDocument13 pagesHistory On The Line Beyond The Archive of Silence: Narratives of Violence of The 1971 Liberation War of BangladeshAJPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond The Archive of Silence Narratives PDFDocument14 pagesBeyond The Archive of Silence Narratives PDFTayyaba AnsariPas encore d'évaluation

- Week8 YasminSaikiaDocument2 pagesWeek8 YasminSaikiaAdnan MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Myth-Busting The Bangladesh War of 1971: Sarmila BoseDocument5 pagesMyth-Busting The Bangladesh War of 1971: Sarmila BoseAwan MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- War & Story Telling Among Bangladeshi FamiliesDocument7 pagesWar & Story Telling Among Bangladeshi FamiliesNaina HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- A Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshDocument13 pagesA Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshTarek FatahPas encore d'évaluation

- Book ReviewDocument4 pagesBook ReviewMuzammil HussainPas encore d'évaluation

- Archiving The Nation State in Feminist PraxisDocument49 pagesArchiving The Nation State in Feminist PraxisesperantePas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971Document9 pagesAnatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971dirtroadPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Document16 pagesAnatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Rage EzekielPas encore d'évaluation

- EWU. GEN 226. Lecture 19. StudentsDocument5 pagesEWU. GEN 226. Lecture 19. StudentsMd SafiPas encore d'évaluation

- 101.pdfl Review Article: Women and Ethnic Cleansing: A History of Partition in India and PakistanDocument11 pages101.pdfl Review Article: Women and Ethnic Cleansing: A History of Partition in India and Pakistanravibunga4489Pas encore d'évaluation

- ChapterDocument80 pagesChapterapurba mandalPas encore d'évaluation

- Dead Reckoning - Docx 11Document4 pagesDead Reckoning - Docx 11Aftab AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Myths of BangladeshDocument16 pagesMyths of BangladeshjohnacresPas encore d'évaluation

- Silence Revealed Womens Experiences DuriDocument28 pagesSilence Revealed Womens Experiences DuriBarnali SahaPas encore d'évaluation

- From Pak-Bangla To Bangladesh, What Went Wrong?Document4 pagesFrom Pak-Bangla To Bangladesh, What Went Wrong?Komal RehmanPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 - Chapter 6 PDFDocument39 pages14 - Chapter 6 PDFPratik BhartiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Proposal: The IIS University, JaipurDocument18 pagesResearch Proposal: The IIS University, JaipurSahina SarkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Silence Revealed Womens - Experiences - DuriDocument14 pagesSilence Revealed Womens - Experiences - DurismrithiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1971 Genocide in BangladeshDocument30 pages1971 Genocide in BangladeshAbir Mahmud ZakariaPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review - " of Blood and Fire" by Jahanara ImamDocument5 pagesBook Review - " of Blood and Fire" by Jahanara ImamSmoll CutiePas encore d'évaluation

- Victimization of Women During India's PartitionDocument5 pagesVictimization of Women During India's PartitionNeelamPas encore d'évaluation

- Mansib School-4Document4 pagesMansib School-4fakesurjo9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Basti by Intizar HussaintDocument19 pagesBasti by Intizar HussaintpriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sabhyasachi Amiyo ReviewDocument12 pagesSabhyasachi Amiyo ReviewBipul BhattacharyaPas encore d'évaluation

- 15 04 Guru Saday BatabyalDocument24 pages15 04 Guru Saday BatabyalAmit PramanikPas encore d'évaluation

- Ilyas Chattha - Looting in The NWFP and Punjab - Property and Violence in The Partition of 1947Document16 pagesIlyas Chattha - Looting in The NWFP and Punjab - Property and Violence in The Partition of 1947sohaibafzal100Pas encore d'évaluation

- My Experience Before and After Visiting The Liberation War MuseumDocument21 pagesMy Experience Before and After Visiting The Liberation War MuseumShourav Roy 1530951030Pas encore d'évaluation

- Partition and WomenDocument16 pagesPartition and WomenbrbrbracademicsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mookerjea-Leonard Disenfranchised BodiesDocument24 pagesMookerjea-Leonard Disenfranchised BodiesAritra ChakrabortiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ba1 Hum118Document7 pagesBa1 Hum118nandhithaPas encore d'évaluation

- India-Pakistan Partition by Kanwaljit KaurDocument13 pagesIndia-Pakistan Partition by Kanwaljit KaurReadnGrowPas encore d'évaluation

- Hisn 12059Document26 pagesHisn 12059Ch NomanPas encore d'évaluation

- Distrurbing FactDocument2 pagesDistrurbing FactSonia ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Humanity Amidst Insanity: Stories of compassion and hope duringD'EverandHumanity Amidst Insanity: Stories of compassion and hope duringPas encore d'évaluation

- Total Thesis of Madhuparna Mitra GuhaDocument345 pagesTotal Thesis of Madhuparna Mitra GuhaSatadal GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Partition of India and Its Enormous Impact On Bengali LiteratureDocument2 pagesPartition of India and Its Enormous Impact On Bengali LiteratureDevolina DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Women in NationalismDocument7 pagesRole of Women in NationalismMehar BediPas encore d'évaluation

- Hom-205 Bangladesh Studies.Document12 pagesHom-205 Bangladesh Studies.Jh HridoyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Other Side of Silence Voices From the Partition of India -- Butalia, Urvashi -- Repr, 2014 -- Penguin Books Ltd -- 369c955426cecacc4a2b0504ed0159b5 -- Anna’s ArchiveDocument280 pagesThe Other Side of Silence Voices From the Partition of India -- Butalia, Urvashi -- Repr, 2014 -- Penguin Books Ltd -- 369c955426cecacc4a2b0504ed0159b5 -- Anna’s ArchiveRitika SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Term PaperDocument5 pagesTerm PaperArihantPas encore d'évaluation

- Women in Partition Literature, Films and MemoirsDocument63 pagesWomen in Partition Literature, Films and MemoirsEhsanPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment - History Real OneDocument8 pagesAssignment - History Real OneIslam For LIFEPas encore d'évaluation

- Debnath Final ThesisDocument63 pagesDebnath Final ThesisKhushi SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Female Freedom Fighters From NEDocument4 pagesFemale Freedom Fighters From NEEquatorPas encore d'évaluation

- Nüshu: The Hidden Identity of Chinese WomenDocument5 pagesNüshu: The Hidden Identity of Chinese WomenAlexandru KerestelyPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Jinnah in PartitionDocument4 pagesRole of Jinnah in PartitionPradipta KunduPas encore d'évaluation

- BIS ASIF Term PaperDocument8 pagesBIS ASIF Term Paperasif7bin7mohsinPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ProposalDocument3 pagesFinal ProposalMadhurima GuhaPas encore d'évaluation

- How Oral Histories and Literary Works Altered Partition StudiesDocument8 pagesHow Oral Histories and Literary Works Altered Partition StudiesSuresh Ningthoujam100% (1)

- Plot Structure and Development of Emotions in Sakuntala, Part IIDocument17 pagesPlot Structure and Development of Emotions in Sakuntala, Part IILiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerow, Plot Structure and The Development of Rasa in The Śakuntalā. Pt. IDocument15 pagesGerow, Plot Structure and The Development of Rasa in The Śakuntalā. Pt. ILiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemistry Reference TablesDocument8 pagesChemistry Reference Tablescauten2100% (1)

- Review SheetDocument8 pagesReview SheetLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- WowowwDocument1 pageWowowwLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Art HistoryDocument2 pagesArt HistoryLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- # of Carbons Name Formula (C: AP Chemistry Chapter 22 - Organic ChemistryDocument5 pages# of Carbons Name Formula (C: AP Chemistry Chapter 22 - Organic ChemistryLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Gerow, Plot Structure and The Development of Rasa in The Śakuntalā. Pt. IDocument15 pagesGerow, Plot Structure and The Development of Rasa in The Śakuntalā. Pt. ILiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Binary CompoundsDocument5 pagesBinary CompoundsLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Man and Superman - The New YorkerDocument12 pagesMan and Superman - The New YorkerLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Apush NotesDocument1 pageApush NotesLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- The Iranian Component of The Nu Ayrī ReligionDocument12 pagesThe Iranian Component of The Nu Ayrī ReligionLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Sat EssayDocument2 pagesSat EssayLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- (239353868) How Did Sleep Become So Nightmarish - NYTimesDocument7 pages(239353868) How Did Sleep Become So Nightmarish - NYTimesLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 27 - Empire and ExpansionDocument9 pagesChapter 27 - Empire and ExpansionLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- VI. The Baleful Black CodesDocument2 pagesVI. The Baleful Black CodesLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Allinson Anievas - Meiji RestorationDocument22 pagesAllinson Anievas - Meiji RestorationLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

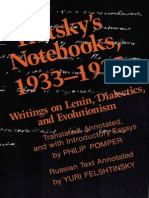

- Trotsky's NotebooksDocument69 pagesTrotsky's NotebooksLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- 17 BollywoodDocument31 pages17 BollywoodsalazarjohannPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioecon TV Presents Alain Badiou at Occidente Portraits, Visions and UtopiaDocument2 pagesBioecon TV Presents Alain Badiou at Occidente Portraits, Visions and UtopiaLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistani Workers in The Middle EastDocument16 pagesPakistani Workers in The Middle EastLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Harvey D - Postmodern Morality PlaysDocument27 pagesHarvey D - Postmodern Morality PlaysLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Harvey D, Hardt and Negri - Commonwealth - An ExchangeDocument10 pagesHarvey D, Hardt and Negri - Commonwealth - An ExchangeLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Loiter Essay in Dissent and Cultural Resistance in Asias CitiesDocument22 pagesWhy Loiter Essay in Dissent and Cultural Resistance in Asias CitiesLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Congress of The Peoples of The East-BakuDocument285 pagesCongress of The Peoples of The East-BakuLiza RPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Humanities Research AssociationDocument4 pagesModern Humanities Research AssociationrimanamhataPas encore d'évaluation

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 22.Document734 pagesMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 22.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Whistling in Peruvian Ayahuasca HealingDocument9 pagesRole of Whistling in Peruvian Ayahuasca HealingjuiceshakePas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Dawat e IslamiDocument62 pagesIntroduction To Dawat e IslamiAli Asghar AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- RekapLaporanSemua RI 2020-01-01Document64 pagesRekapLaporanSemua RI 2020-01-01Christy TirtayasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Akshara Mana Malai - A Garland of Letters for ArunachalaDocument18 pagesAkshara Mana Malai - A Garland of Letters for ArunachalaVishalSelvanPas encore d'évaluation

- RavanaDocument4 pagesRavanaabctandonPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 8 Kindergarten Teachers GuideDocument10 pages1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 8 Kindergarten Teachers GuideRitchie FamarinPas encore d'évaluation

- The China Road Motorcycle Diaries: Misbehaving MonkDocument7 pagesThe China Road Motorcycle Diaries: Misbehaving MonkCarla King100% (3)

- Test Bank For The Economics of Money Banking and Financial Markets 7th Canadian by MishkinDocument36 pagesTest Bank For The Economics of Money Banking and Financial Markets 7th Canadian by Mishkinordainer.cerule2q8q5g100% (32)

- Jesus - Who Is He?Document8 pagesJesus - Who Is He?Sam ONiPas encore d'évaluation

- RMY 101 Assignment Fall 2020 InstructionsDocument5 pagesRMY 101 Assignment Fall 2020 InstructionsAbass GblaPas encore d'évaluation

- God Harmony DictationsDocument4 pagesGod Harmony DictationsAbraham DIKAPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of Indian Philosophy Volume 1Document6 pagesA History of Indian Philosophy Volume 1domenor7Pas encore d'évaluation

- General Holidays List - 2021Document1 pageGeneral Holidays List - 2021milan mottaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ayat-Ayat Ruqyah Plus: Al Fatihah 1-7Document4 pagesAyat-Ayat Ruqyah Plus: Al Fatihah 1-7Vonni Triana Hersa0% (1)

- Syllabus YTE Version0.2Document10 pagesSyllabus YTE Version0.2Sam MeshramPas encore d'évaluation

- Chronicles of Eri by Connor1Document496 pagesChronicles of Eri by Connor1Pedro Duracenko0% (1)