Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Digest Set 3

Transféré par

Basri JayCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Digest Set 3

Transféré par

Basri JayDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

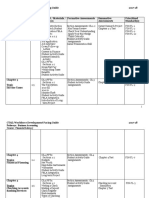

1. Hererra v Petro Phil 146 SCRA 385 2. Ronio v Gomez 83 PHIL 890 3. De Lima v Laguna? 160 SCRA 70 4.

Nakpil v Ca 160 SCRA 334 5. Sangrada v Villanueva __ SCRA 215 6. Insular v Spouses Salazar 159 SCRA 133 7. Equitable v Liwanag 32 SCRA 293 8. Heniza v Sy 6 SCRA 20 9. Manila Trading v Tamaraw 47 PHIL 513 10. Delgado v Alfonso 44 PHIL 739 11. Lotero v Siu Liong 54 PHIL 272 8Sangrador vs. Valderrama, 168 SCRA 215.

HERRERA vs PETROPHIL CORP. [G.R. No. L-48349, December 29, 1986] CRUZ, J.

FACTS:

On December 5, 1969, Herrera and ESSO Standard, (later substituted by Petrophil Corp.,) entered into a lease agreement, whereby the former leased to the latter a portion of his property for a period of 20yrs. subject to the condition that monthly rentals should be paid and there should be an advance payment of rentals for the first eight years of the contract, to which ESSO paid on December 31, 1969. However, ESSO deducted the amount of 101, 010.73 as interest or discount for the eight years advance rental.

On August 20, 1970, ESSO informed Herrera that there had been a mistake in the computation of the interest and paid an additional sum of 2,182.70; thus, it was reduced to 98, 828.03.

As such, Herrera sued ESSO for the sum of 98, 828.03, with interest, claiming that this had been illegally deducted to him in violation of the Usury Law.

ESSO argued that amount deducted was not usurious interest but rather a discount given to it for paying the rentals in advance. Judgment on the pleadings was rendered in favor of ESSO. Thus, the matter was elevated to the SC for only questions of law was involve. ISSUE: W/N the contract between the parties is one of loan or lease.

RULING:

Contract between the parties is one of lease and not of loan. It is clearly denominated a "LEASE AGREEMENT." Nowhere in the contract is there any showing that the parties intended a loan rather than a lease. The provision for the payment of rentals in advance cannot be construed as a repayment of a loan because there was no grant or forbearance of money as to constitute an indebtedness on the part of the lessor. On the contrary, the defendant-appellee was discharging its obligation in advance by paying the eight years rentals, and it was for this advance payment that it was getting a rebate or discount.

There is no usury in this case because no money was given by the defendant-appellee to the plaintiffappellant, nor did it allow him to use its money already in his possession. There was neither loan nor forbearance but a mere discount which the plaintiff-appellant allowed the defendant-appellee to deduct from the total payments because they were being made in advance for eight years. The discount was in effect a reduction of the rentals which the lessor had the right to determine, and any reduction thereof, by any amount, would not contravene the Usury Law.

The difference between a discount and a loan or forbearance is that the former does not have to be repaid. The loan or forbearance is subject to repayment and is therefore governed by the laws on usury.

To constitute usury, "there must be loan or forbearance; the loan must be of money or something circulating as money; it must be repayable absolutely and in all events; and something must be exacted for the use of the money in excess of and in addition to interest allowed by law."

It has been held that the elements of usury are (1) a loan, express or implied; (2) an understanding between the parties that the money lent shall or may be returned; that for such loan a greater rate or interest that is allowed by law shall be paid, or agreed to

be paid, as the case may be; and (4) a corrupt intent to take more than the legal rate for the use of money loaned. Unless these four things concur in every transaction, it is safe to affirm that no case of usury can be declared. G.R. No. L-1927 May 31, 1949 CRISTOBAL ROO, petitioner, vs. JOSE L. GOMEZ, ET AL., respondents. *Usurious Transactions #6 (round 2)STATEMENT OF FACTS: On October 5, 1944, Cristobal Roo received as a loan fromJose L. Gomez P4,000.00 in Japanese fiat money (mickey mouse money). The contractof loan is under the condition that said loan will not earn interest and that it will be paid in the currency then prevailing one year after the execution of the contract. After ayear, a collection suit was filed by respondent Gomez against petitioner Rono to collect the latters debt. Subsequently, t he trial court ruled in favor of Gomez. The courtordered Rono to pay the respondent an amount of P4,000.00 in Philippine currencywhich was then the prevailing currency at the time of payment. Contending suchdecision, Rono insists that the contract taken in favor of respondent is contrary to law,public order and good morals since his loan then of P4,000.00 mickey mouse money is equivalent only to P100.00 of the Philippine currency which is the prevailing currencyat the time of payment. CONTENTION OF THE PETITIONER: Roo asserts that the decision of the trial courtruling in favor of respondent is contrary to the Usury law, because on the basis ofcalculations by Government experts he only received the equivalent of P100 Philippinepesos and now he is required to give four thousand pesos or interest greatly in excessof the lawful rates. CONTENTION OF THE RESPONDENT: That both parties agreed that the loanedamount of P4,000.00 mickey mouse money be paid in the currency prevailing by theend of one year. The civil cod e supports such agreement when it says "obligationsarising from contracts shall have the force of law between the contracting parties andmust be performed in accordance with their stipulations" (Article 1091). RESOLUTION OF SC: The SC ruled that that the contract between the parties is an aleatoty contract.The eventual gain of Gomez is not interest within the meaning of the Usury law.In the first place, Rono is not paying an interest. Such is evidenced by the fact that in hispromissory note, he indicated that the money loaned will not earn any interest. Furthermore, both parties clearly agreed at the time of the execution of thecontract that the loaned money ( P4,000.00 mickey mouse ) will be paid in the currency prevailing by the end of the s tipulated period of one year.

The devaluation of the Mickey mouse money is due to an event unforseable byany man; that the increased intrinsic value and purchasing power of the current moneyis consequence of an event (change of currency) which at the time of the contractneither party knew would certainly happen within the period of one year. However, bothparties subjected their rights and obligations to that contingency. Thus, the contract inquestion is legal and obligatory and is not subject to the operation of the Usury law DELIMA VS LAGUNA TAYABAS Petitioners moved for a reconsideration of this decision seeking its modification so that the legal interest awarded by the Appellate, Court will start to run from the date of the decision of the trial court on December 27, 1963 instead of January 31, 1972, the date of the decision of the Court of Appeals. Petitioner potenciano Requijo as heir of the deceased Petra de la Cruz further sought an increase in the civil indemnity of P3,000.00 to P 12,000.00. The Appellate Court denied the motion for reconsideration holding that since the plaintiffs did not appeal from the failure of the court a quo to award interest on the damages and that the court on its own discretion awarded such interest in view of Art. 2210 of the Civil Code, the effectivity of 5 the interest should not be rolled back to the time the decision of the court a quo was rendered. Hence this petition. The assignment of errors raised the following issues, to wit: 1) Whether or not the Court of Appeal; erred in granting legal interest on damages to start only from the date of its decision instead of from the date of the trial court's decision; 2) Whether or not the Court of Appeals erred in not increasing the indemnity for the death of Petra de La Cruz (in Civil Case No. SP-240) from P3,000 to P12,000.00. We find merit in the petition. Under the first issue, petitioners contend that the ruling of she Appellate Court departs from the consistent rulings of this court that the award of the legal rate of interest should be computed from the promulgation of the decision of the tonal court. Respondents counter that petitioners having failed to appeal from the lower court's decision they. are now precluded from questioning the ruling of the Court of Appeals. It is true that the rule is well-settled that a party cannot impugn the correctness of a judgment not appealed from by him, and while he may make counter assignment of errors, he can do so only to 6 sustain the judgment on other grounds but not to seek modification or reversal thereof, for in 7 such case he must appeal. A party who does not appeal from the decision may not obtain any affirmative relief from the appellate court other than what he has obtained from the lower court, if any, whose decision is brought up on appeal. Moreover, under the circumstances of this case where the heirs of the victim in the traffic accident chose not to appeal in the hope that the transportation company will pay the damages awarded by the lower court but unfortunately said company still appealed to the Court of Appeals, which step was obviously dilatory and oppressive of the rights of the said claimants: that the case had been pending in court for about 30 years from the date of the accident in 1958 so that as an exception to the general rule aforestated, the said heirs who did not appeal the judgment, should 12 be afforded equitable relief by the courts as it must be vigilant for their protection. The claim for legal interest and increase in the indemnity should be entertained in spite of the failure of the claimants to appeal the judgment.

13 4

We hold that the legal interest of six percent (6)

on the amounts adjudged in favor of petitioners

should start from the time of the rendition of the trial court's decision on December 27, 1963 instead of January 31, 1972, the promulgation of the decision of the Court of Appeals. WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby GRANTED, the subject decision is modified in that the legal interest on the damages awarded to petitioners commences from the date of the decision of the court a quo until actual payment while the civil indemnity for the death of Petra de la Cruz is increased to P 30,000.00.

This judgment is immediately executory and no motion for extension of time to file motion for reconsideration shall be entertained. Consolidated Case Nakpil & Sons et. al. vs. Court of Appeals October 3, 1986 160 SCRA 334 Ponented: Justice Paras Facts: In the RTC of Manila, PBA filed a complaint for damages and thus was appealed to the CA where judgment was modified as what the RTC rendered in favor of the plaintiff. PBA constructed a building whereby the construction was undertaken by United Construction Inc, (UCI). Approved by the president of PBA, the plans and specification were prepared by Nakpil & Sons. August 2, 1968, earthquake hit Manila and thus damaging properties where the building of PBA was one of which. November 29 of that same year, plaintiff PBA filed suit for recovery of damages against the UCI. The UCI in turned filed suit against Nakpil & Sons, by which in March 3, 1969 filed their written stipulation. In the RTC, technical issues were submitted to Commissioner Hizon and as for other issues the Court resolved. Commissioner sustained that the building was caused directly by the earthquake and maintained that the specification were not followed. Issue(SC issue): Whether or not an Act of God-fortuitous event, exempts liability from parties who are otherwise liable because of their negligence?

Held: Although the general rule for fortuitous events stated in Article 1174 of the Civil Code exempts liability when there is an Act of God, thus if in the concurrence of such event there be fraud, negligence, delay in the performance of the obligation, the obligor cannot escape liability therefore there can be an action for recovery of damages. The negligence of the defendant was shown when and proved that there was an alteration of the plans and specification that had been so stipulated among them. Therefore, therefore there should be no question that NAKPIL and UNITED are liable for damages because of the collapse of the building. The Court of Appeals affirmed the finding of the trial court based on the report of the Commissioner that the total amount required to repair the PBA building and to restore it to tenantable condition was P900,000.00 inasmuch as it was not initially a total loss. However, while the trial court awarded the PBA said amount as damages, plus unrealized rental income for onehalf year, the Court of Appeals modified the amount by awarding in favor of PBA an additional sum of P200,000.00 representing the damage suffered by the PBA building as a result of another earthquake that occurred on April 7, 1970 (L-47896, Vol. I, p. 92). The PBA in its brief insists that the proper award should be P1,830,000.00 representing the total value of the building (L-47896, PBA's No. 1 Assignment of Error, p. 19), while both the NAKPILS and UNITED question the additional award of P200,000.00 in favor of the PBA (L- 47851, NAKPIL's Brief as Petitioner, p. 6, UNITED's Brief as Petitioner, p. 25). The PBA further urges that the unrealized rental income awarded to it should not be limited to a period of one-half year but should be computed on a continuing basis at the rate of P178,671.76 a year until the judgment for the principal amount shall have been satisfied L- 47896, PBA's No. 11 Assignment of Errors, p. 19).

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is hereby MODIFIED and considering the special and environmental circumstances of this case, We deem it reasonable to render a decision imposing, as We do hereby impose, upon the defendant and the third-party defendants (with the exception of Roman Ozaeta) asolidary (Art. 1723, Civil Code, Supra, p. 10) indemnity in favor of the

Philippine Bar Association of FIVE MILLION (P5,000,000.00) Pesos to cover all damages (with the exception of attorney's fees) occasioned by the loss of the building (including interest charges and lost rentals) and an additional ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND (P100,000.00) Pesos as and for attorney's fees, the total sum being payable upon the finality of this decision. Upon failure to pay on such finality, twelve (12%) per cent interest per annum shall be imposed upon afore-mentioned amounts from finality until paid. Solidary costs against the defendant and third-party defendants (except Roman Ozaeta).

SANGRADOR VS VALDERAMA After carefully reviewing the evidence, We are convinced that the trial court erred in finding that the loan was P1,400,000 as stated in the promissory note (Exh. B) and deed of mortgage. Like the trial court, We do not believe defendant Valderrama's allegation that he did not notice that the amount stated in the promissory note was P1,400,000, instead of only P1,000,000, until demands for payment were sent to him by the plaintiffs' counsel. But neither do We believe the plaintiff Evelyn Sangrador's allegation that besides the sum of P1,000,000 admittedly received by the defendants and evidenced by checks and receipts, she also gave them P400,000.00 in cash without receipt. This is a case, therefore, where both parties prevaricated. Obviously, the P400,000 that was added to the principal represents a hidden interest charge for the promissory note contains no express provision fixing the rate of interest on the loan. Insular Bank of Asia and AmericaVs. Spouses Salazar (159 SCRA 133)I t i s t h e r u l e t h a t e s c a l a t i o n c l a u s e s a r e v a l i d s t i p u l a t i o n s i n commercial contracts to maintain fiscal stability and to retain the valueof money on long term contracts. However, the enforcement of such stipulations are subject to certain conditions.

A provision of a contract which calls for an increase in price in the event of an increase in certain costs. For example, an escalation clause may specify that rent due will increase with inflation. opposite of de-escalation clause.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Corp Reviewer - LadiaDocument87 pagesCorp Reviewer - Ladiadpante100% (6)

- Vinoya Vs NLRCDocument28 pagesVinoya Vs NLRCBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Vinoya Vs NLRCDocument28 pagesVinoya Vs NLRCBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Gardose V TarrozaDocument2 pagesGardose V TarrozalittlemissbelieverPas encore d'évaluation

- Beginners Guide To Market ManipulationDocument53 pagesBeginners Guide To Market ManipulationAnderson Bragagnolo100% (10)

- Balloon Loan Calculator: InputsDocument9 pagesBalloon Loan Calculator: Inputsmy.nafi.pmp5283Pas encore d'évaluation

- Red Line TransportDocument8 pagesRed Line TransportBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Article 7 When Light Felonies Are PunishableDocument3 pagesArticle 7 When Light Felonies Are PunishableBasri Jay100% (3)

- Important Tips On The Law On Sales - Edited 2009Document57 pagesImportant Tips On The Law On Sales - Edited 2009JanetGraceDalisayFabreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax CasesDocument50 pagesTax CasesBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Red Line Transportation Co. vs. Rural Transit Co. GR No. 41570 - Sept. 6, 1934 FactsDocument10 pagesRed Line Transportation Co. vs. Rural Transit Co. GR No. 41570 - Sept. 6, 1934 FactsBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- 0809 B&E SeptDocument118 pages0809 B&E Septhsrivastava703Pas encore d'évaluation

- Part 3 Case Digest Eladla de Lima vs. Laguna Tayabas CoDocument13 pagesPart 3 Case Digest Eladla de Lima vs. Laguna Tayabas CoJay-r Mercado ValenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Romualdez Vs Civil Service CommissionDocument1 pageRomualdez Vs Civil Service CommissionFrancis Gillean OrpillaPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. 164785, March 15, 2010Document19 pagesG.R. No. 164785, March 15, 2010Michelangelo TiuPas encore d'évaluation

- Bahasa Inggeris Peralihan Akhir Tahun Tahun Paper 2 2014Document5 pagesBahasa Inggeris Peralihan Akhir Tahun Tahun Paper 2 2014Nazurah Eryna100% (2)

- Spouses Antonio and Lolita TanDocument1 pageSpouses Antonio and Lolita TanMacPas encore d'évaluation

- SCB GarudaDocument34 pagesSCB Garudaisham1989Pas encore d'évaluation

- 16 BPI V RoyecaDocument3 pages16 BPI V RoyecarPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Provisions 1. Uy Tong vs. Ca 161 Scra 383 FactsDocument16 pagesCommon Provisions 1. Uy Tong vs. Ca 161 Scra 383 FactsDonna RizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Guevarra Vs EalaDocument18 pagesGuevarra Vs Ealaafro yowPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank of America v. American RealtyDocument3 pagesBank of America v. American RealtyMica MndzPas encore d'évaluation

- Cua Lai Chu Vs LaquiDocument2 pagesCua Lai Chu Vs LaquiEM RGPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Bank of Communications vs. Basic Polyprinters and Packaging CorporationDocument2 pagesPhilippine Bank of Communications vs. Basic Polyprinters and Packaging CorporationCharlie BartolomePas encore d'évaluation

- DfsdfsDocument1 pageDfsdfsBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 39 DigestDocument41 pagesRule 39 DigestBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Victorias Milling Co. Inc. v. CADocument20 pagesVictorias Milling Co. Inc. v. CADexter CircaPas encore d'évaluation

- SPCL Case DigestsDocument107 pagesSPCL Case DigestsMahaize TayawaPas encore d'évaluation

- ADDISON V. FELIX (August 03, 1918) FactsDocument1 pageADDISON V. FELIX (August 03, 1918) FactsMikkaEllaAnclaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prudential Vs AlviarDocument2 pagesPrudential Vs AlviarKen MarcaidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lodge BillDocument5 pagesLodge BillRammohanreddy Rajidi33% (6)

- 12 - Edrada vs. Ramos, 468 SCRA 597, G.R. No. 154413 August 31, 2005Document7 pages12 - Edrada vs. Ramos, 468 SCRA 597, G.R. No. 154413 August 31, 2005gerlie22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biñan Steel Corporation Vs CADocument7 pagesBiñan Steel Corporation Vs CAirish7erialcPas encore d'évaluation

- Hechanova vs. AdilDocument1 pageHechanova vs. AdilAnne Kerstine BastinenPas encore d'évaluation

- Nature of Bank DepositsDocument2 pagesNature of Bank DepositsJamie del CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Acme Shoe V CaDocument2 pagesAcme Shoe V CaCatherine MerillenoPas encore d'évaluation

- G.R. No. L-18751, L-18915 - Philippine National Bank v. PicornellDocument9 pagesG.R. No. L-18751, L-18915 - Philippine National Bank v. PicornellJaana AlbanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Rule 18 Monzon Vs RelovaDocument2 pagesRule 18 Monzon Vs RelovaManu SalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Obligations of The PartnersDocument3 pagesObligations of The PartnersBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Obligations of The PartnersDocument3 pagesObligations of The PartnersBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Gasan Vs MarasiganDocument5 pagesGasan Vs MarasiganBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- California Vs Pioneer Insurance Case Digest - AdrDocument2 pagesCalifornia Vs Pioneer Insurance Case Digest - AdrJuliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pasig Agri Vs Nievarez Case DigestDocument2 pagesPasig Agri Vs Nievarez Case DigestRalph Christian Lusanta FuentesPas encore d'évaluation

- Credit TransDocument3 pagesCredit Transalliah SolitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bpi V CA 232 Scra302Document11 pagesBpi V CA 232 Scra302frank japosPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic Vs BagtasDocument2 pagesRepublic Vs BagtasguapaphroditePas encore d'évaluation

- Gozun v. Mercado (2006)Document1 pageGozun v. Mercado (2006)Kaulayaw PormentoPas encore d'évaluation

- PNB V PicornellDocument1 pagePNB V PicornellEinstein NewtonPas encore d'évaluation

- Sectrans DigestDocument100 pagesSectrans Digest2CPas encore d'évaluation

- Digest Credit Trans CasesDocument7 pagesDigest Credit Trans CasesGracelyn Enriquez Bellingan100% (1)

- Cases - Negotiable Instruments (Week 4)Document163 pagesCases - Negotiable Instruments (Week 4)Gelyssa Endozo Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Some Jurisprudence On Alternative Dispute ResolutionDocument13 pagesSome Jurisprudence On Alternative Dispute ResolutionmastaacaPas encore d'évaluation

- General ProvisionsDocument47 pagesGeneral ProvisionsTricia SibalPas encore d'évaluation

- Group I Letters of CreditDocument9 pagesGroup I Letters of CreditYvettePas encore d'évaluation

- Pena Vs AparicioDocument8 pagesPena Vs AparicioShari ThompsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Credit Cases For Digest PledgemortgageDocument11 pagesCredit Cases For Digest PledgemortgageMel Manatad0% (1)

- Serrano vs. CBDocument1 pageSerrano vs. CBChicoRodrigoBantayogPas encore d'évaluation

- 84 - Tagatac v. JimenezDocument4 pages84 - Tagatac v. JimenezJude Raphael S. FanilaPas encore d'évaluation

- 51 Prudencio Vs CADocument8 pages51 Prudencio Vs CACharm Divina LascotaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dotimas - Credit Trans Digest - GR L16106Document2 pagesDotimas - Credit Trans Digest - GR L16106Christopher Jan DotimasPas encore d'évaluation

- Victorias Milling v. CA, G.R. No. 117356, June 19, 2000Document3 pagesVictorias Milling v. CA, G.R. No. 117356, June 19, 2000Carie LawyerrPas encore d'évaluation

- Retail Trade Liberalization Act of 2000Document22 pagesRetail Trade Liberalization Act of 2000Tukne SanzPas encore d'évaluation

- LIM FILCRO Illegal RecruitmentDocument2 pagesLIM FILCRO Illegal RecruitmentVivienne Nicole LimPas encore d'évaluation

- The Law On Alternative Dispute Resolution 01-2Document144 pagesThe Law On Alternative Dispute Resolution 01-2Grace Managuelod GabuyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Tolentino v. Gonzales Sy ChiamDocument4 pagesTolentino v. Gonzales Sy ChiamRengie GaloPas encore d'évaluation

- RP Vs Fncbny DigestDocument2 pagesRP Vs Fncbny Digestjim jimPas encore d'évaluation

- Gilat Satellite Networks, Ltd. vs. UCPBDocument4 pagesGilat Satellite Networks, Ltd. vs. UCPBJeffrey MedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 RCBC Savings Bank V OdradaDocument2 pages07 RCBC Savings Bank V OdradaAnonymous bOncqbp8yiPas encore d'évaluation

- LUCMAN Vs MALAWIDocument2 pagesLUCMAN Vs MALAWIakimo0% (1)

- Culaba VS Ca PDFDocument15 pagesCulaba VS Ca PDFJohn Dy Castro FlautaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ford Vs CADocument5 pagesFord Vs CAEller-JedManalacMendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- PCI Leasing vs. Trojan Metal Industries Inc., Et Al.Document8 pagesPCI Leasing vs. Trojan Metal Industries Inc., Et Al.GerardPeterMarianoPas encore d'évaluation

- "Environmental Courts" Introduction History Factors in Success List of Courts Court Guidelines ReferencesDocument41 pages"Environmental Courts" Introduction History Factors in Success List of Courts Court Guidelines ReferencesSheila Mae CabahugPas encore d'évaluation

- NIL 02 Areza Vs Express Savings Bank PDFDocument23 pagesNIL 02 Areza Vs Express Savings Bank PDFnette PagulayanPas encore d'évaluation

- Patrimonio Vs GutierrezDocument1 pagePatrimonio Vs GutierrezBruce WaynePas encore d'évaluation

- Credit DigestsDocument55 pagesCredit DigestsJerome MoradaPas encore d'évaluation

- GSIS Vs CorderoDocument2 pagesGSIS Vs CorderoMei SuyatPas encore d'évaluation

- Spouses Puerto vs. Court of Appeals (G.R. 138210)Document12 pagesSpouses Puerto vs. Court of Appeals (G.R. 138210)Gretel MañalacPas encore d'évaluation

- First Division G.R. No. 149683. June 16, 2003 Iloilo Traders Finance Inc., Petitioner, V. Heirs of OscarDocument5 pagesFirst Division G.R. No. 149683. June 16, 2003 Iloilo Traders Finance Inc., Petitioner, V. Heirs of Oscarmaximum jicaPas encore d'évaluation

- Deed of Land Title - The MistressDocument1 pageDeed of Land Title - The MistressBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Wagering ContractDocument1 pageWagering ContractBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Ecommerce CasesDocument7 pages1 Ecommerce CasesBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Tax CasesDocument38 pagesTax CasesBasri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Cases Feb 16Document11 pagesCases Feb 16Basri JayPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Procedure IntroductionDocument7 pagesCivil Procedure IntroductionRaffy RoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Administered Interest Rates in IndiaDocument17 pagesAdministered Interest Rates in IndiatPas encore d'évaluation

- Pelzer Company Reconciled Its Bank and Book Statement Balances ofDocument2 pagesPelzer Company Reconciled Its Bank and Book Statement Balances ofAmit PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Commercial Banking Project ReportDocument44 pagesCommercial Banking Project ReportAyaz Qaiser100% (1)

- Global Premium Office Rent Tracker Q4 2016Document6 pagesGlobal Premium Office Rent Tracker Q4 2016Hoi MunPas encore d'évaluation

- Sources of International FinancingDocument6 pagesSources of International FinancingSabha Pathy100% (2)

- 2 - Globalization of World EconomicsDocument12 pages2 - Globalization of World EconomicsMargie Musngi ValerioPas encore d'évaluation

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestJohn Robert BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pacing Guide-Financial LiteracyDocument6 pagesPacing Guide-Financial Literacyapi-377548294Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Banking and Financial Institutions (Physical Security Measures) Regulations, 2014Document11 pagesThe Banking and Financial Institutions (Physical Security Measures) Regulations, 2014Nanda Win LwinPas encore d'évaluation

- IDBIDocument10 pagesIDBIArun ElanghoPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit - 3 Bank Reconciliation StatementDocument21 pagesUnit - 3 Bank Reconciliation StatementMrutyunjay SaramandalPas encore d'évaluation

- Hapter EST ANK: Ultiple Choice QuestionsDocument19 pagesHapter EST ANK: Ultiple Choice QuestionsMalinga LungaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cash Book & Bank Reconciliation StatementDocument2 pagesCash Book & Bank Reconciliation Statementst_mosviPas encore d'évaluation

- Golden RulesDocument4 pagesGolden RulesCharlie True FriendPas encore d'évaluation

- E - Commerce Chapter 11Document19 pagesE - Commerce Chapter 11Md. RuHul A.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Joshua P. Salce Bsabm Case Digest 6Document2 pagesJoshua P. Salce Bsabm Case Digest 6Joshua P. SalcePas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Assistance Completion Report: Consulting ServicesDocument1 pageTechnical Assistance Completion Report: Consulting Serviceshicko85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Banks in Indian EconomyDocument2 pagesRole of Banks in Indian EconomyPriyanka MuppuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of Study of Employee Engagement Practices in Banking IndustryDocument82 pagesAnalysis of Study of Employee Engagement Practices in Banking IndustryRahul SoganiPas encore d'évaluation

- Performance Appraisal in Banking Sector by Ekta BhatiaDocument102 pagesPerformance Appraisal in Banking Sector by Ekta BhatiaManjuPas encore d'évaluation

- On May 31 2015 Reber Company Had A Cash BalanceDocument1 pageOn May 31 2015 Reber Company Had A Cash BalanceAmit PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Matrix Assessment of Pan-European Banks Capital Positions Relating To Basel III: Jan. '11Document98 pagesMatrix Assessment of Pan-European Banks Capital Positions Relating To Basel III: Jan. '11creditplumberPas encore d'évaluation

- BST Project Class 11Document14 pagesBST Project Class 11nobe gamingPas encore d'évaluation