Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Dysphagia

Transféré par

Khairul MustafaDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dysphagia

Transféré par

Khairul MustafaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Update on Assessment and Management of Dysphagia Post Stroke

Giselle Carnaby-Mann, MPH, PhD, Kerry Lenius, MS, and Michael A. Crary, PhD

Abstract: Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) following stroke is a common problem and is associated with significant morbidity. Early identification and management has been reported to result in improved outcomes for stroke patients and is now a standard recommendation for all certified stroke centers in the USA. This article provides an update on issues surrounding current practices in screening, evaluation and treatment for dysphagia following stroke.

Regardless of method, an appropriate dysphagia assessment tool should be readily accessible, validated in a population of acute stroke patients, and should also demonstrate strong inter-observer reliability. Furthermore, such a measure should have the potential to grade severity of identified dysphagia. The most frequently used swallowing assessment method is the clinical bedside evaluation. These exams have been traditionally designed and performed by speech language pathologists. Although the clinical examination is reported to be less sensitive in the identification of dysphagia and aspiration when compared to alternative instrumental assessment techniques, several authors agree that it does confer valuable information to the prognosis and management of stroke patients with swallowing impairment.8, 11 Several forms of this exam have been suggested; however psychometric evaluations of these tests have found them to be highly variable in their ability to reliably detect dysphagia.12 Disparity among studies in the criteria for identifying patients with dysphagia and the over reliance on reported findings contributes to this heterogeneity in outcomes both within and across studies. Videofluoroscopic assessment of swallowing (modified barium swallow) is also frequently used to investigate dysphagia. This exam involves the dynamic recording of a patient swallowing different consistencies of food impregnated with barium while under x-ray. Images of the swallowing actions are then stored for later analysis by both a speech language pathologist and radiologist. Although often regarded as the gold standard for swallowing evaluation, this view is not universally accepted.12, 13 Videofluoroscopic protocols vary widely between clinicians and institutions. Additionally, reliability estimates for the interpretation of the physiologic findings from this technique are low. High reliability estimates have only been reported for a single variable, the identification of an aspiration event.14 In addition, the radiological setting does not mimic normal eating conditions and often underestimates the time required for patients to consume food. Although the radiation exposure from a single study is considered acceptable, frequent repetition of this examination is undesirable. Furthermore, a patients physical or cognitive limitations may completely prevent evaluation using this technique. Martino, Pron, and Diamant reported survey data which indicated that, 71% of respondent dysphagia clinicians (speech language pathologists) performed a complete clinical examination of dysphagia.15 Conversely, only 36% of these clinicians completed an instrumental swallowing examination. Moreover, the instrumental examinations were rarely completed in the absence of the full clinical examination. Thus, the results of this survey strongly suggested that the

Northeast Florida Medicine Vol. 58, No. 2 2007 31

Introduction

Swallowing dysfunction after stroke is common and present in about 30% -60% of patients with acute stroke.1-5 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) estimates that dysphagia resulting from stroke and neurological deficit affects approximately 300,000-600,000 persons each year in the USA. Dysphagia following stroke is associated with an increased risk of complications such as aspiration pneumonia (RR, 3.17)6, dehydration, increased mortality (RR: 6.12), comorbidity (RR 2.11), poorer long-term outcome (RR 1.63), and greater health care costs.7,8 Although overt dysphagia is reported to have a high rate of spontaneous resolution, a substantial number of stroke survivors still demonstrate dysphagia characteristics well beyond the rehabilitation period. Indeed, for some patients this can be a permanent condition requiring long-term tube feeding.9, 8 These persisting deficits impact physical and social functioning, quality of life for patients and caregivers, community re-entry opportunities, and health care resource utilization.

Identification of Dysphagia

The reported high incidence of dysphagia following stoke, and the consequent risks associated, emphasize the need for early identification and evaluation of dysphagia. Current American Stroke Association (ASA) stroke management guidelines recommend completion of a comprehensive clinical assessment for any stroke patient suspected to have dysphagia.10 Identifying patients who are at risk for dysphagia following stroke, however, remains a difficult task. Several methods have been proposed for the evaluation of dysphagia following stroke. No consensus currently exists on a standard method of assessment. Investigators have utilized methods ranging from subjective impressions such as observations of coughing following liquid ingestion, to global impressions of function, or the use of computerized instrumental techniques (e.g. videofluoroscopy and videoendoscopy).

Address Correspondence to: Giselle Carnaby-Mann, MPH, PhD, Associate Research Scientist, Swallowing Research Laboratory, Dept. of Behavioral Science & Community Health, University of Florida. Phone: 352-273-6164. Fax: 352-392-7018. Email: gmann@phhp.ufl.edu.

www . DCMS online . org

clinical examination of swallowing is the primary method of assessment among practicing clinicians. The Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability (MASA) is one clinical measure of dysphagia that has demonstrated strong reliability, has been validated (against videofluoroscopic and videoendoscopic swallowing examination) in several populations of stroke patients, provides a numerical score reflecting the severity of dysphagia symptoms, and is sensitive to change in patient performance over time.16 This exam has been extensively evaluated for use as a bedside swallowing assessment for stroke patients.The MASA demonstrates strong psychometric properties compared to radiographic swallowing studies (SE: 73%; SP: 89%) in stroke patients. This clinical tool provides good inter-observer reliability for dysphagia (kappa = 0.85) and aspiration (kappa = 0.74). The 24 items combine to provide a total score and cut-off criteria for dysphagia and aspiration severity. This tool can be used to document change in swallow function over time. The MASA has been and continues to be used in several large-scale studies of dysphagia.17,18 Further, the MASA is considered simple to use and has been reported by several authors to have facilitated dysphagia identification following stroke and promoted more efficient use of scarce resources.

Correspondingly, the JCAHO now states that dysphagia screening for all stroke admissions is one of the standardized measures that certified stroke centers in the USA must implement. Unfortunately, there is no concordance on which screening method should be used to identify such at risk stroke patients. Currently many facilities utilize some form of swallow screening tool; often a water swallowing task or variant of this. Many centers, however, also modify these protocols to suit their needs, thus confounding any associated validity or reliability estimates. Clearly, more research is required to develop an acceptable dysphagia screening measure that provides accuracy, safety, simplicity, acceptable financial cost and benefit in absolute terms to the stroke population.

Management of Dysphagia

Screening for Dysphagia

Formal screening for dysphagia in all patients with acute stroke has recently become a recommended strategy, by the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), to promote better intra-hospital care.19 The concept that complications of swallowing disorders are preventable if they are recognized early and managed appropriately underlies much of what is often termed screening for dysphagia. While most of us support the notion of making informed judgments on health status from physical examination, the identification of which tool to use for screening remains controversial.13 Martino et al.13 in a recent systematic review of screening for dysphagia following stroke, reported that most published clinical dysphagia evaluation methods were related to observation of symptomology and or laryngeal signs (63%) and most of the outcomes were inferred from physiology (74%). This author also found that the screening accuracy of these tools was limited because of poor study design and the predominant use of aspiration as the single diagnostic reference. Nonetheless, they concluded that while the evidence for benefit from dysphagia screening was limited, it did suggest an associated reduction in pneumonia, length of hospital stay, personnel costs, and patient charges. In follow-up to this, Hinchey et al, reported on a national stroke practice study that investigated the impact of formal dysphagia screening on the incidence of pneumonia following stroke.20 This author found that the use of a formal screens prevented pneumonia even after adjustment for stroke severity and suggested that by instituting formal dysphagia screening procedures up to 8,300 lives might be saved and 40,000 pneumonias prevented annually.20

32 Vol. 58, No. 2 2007 Northeast Florida Medicine

The management of dysphagia is aimed at providing adequate nutrition to a patient in the safest, most efficient way. If swallowing is deemed unsafe, a management plan is formulated in which patients may be taught a range of feeding exercises, maneuvers, or strategies to facilitate oral feeding. In some cases, this plan may include the recommendation of alternative feeding methods. Swallowing treatment can be classified into either indirect (compensatory) or direct methods. Compensatory methods are those strategies or maneuvers aimed at eliminating the symptoms of dysphagia without directly altering the swallowing physiology. These include techniques such as altering head or body position, altering food delivery methods, or modifying the type of food consistency consumed. Direct swallowing treatments are designed to change the swallowing physiology and require direct participation by the patient. These include techniques such as training patients to hold their breath while swallowing and then to cough following a swallow to clear any residual material from the hypopharynx (i.e. supraglottic swallow), various forms of sensory stimulation, or even the use of surface electromyographic biofeedback while swallowing. While a range of different techniques for swallow rehabilitation exist, the relative efficacy of the various techniques or programs of treatment is difficult to assess. Current practice in the treatment of dysphagia following stroke is haphazard, both across and within facilities. Patients may receive various combinations of behavioral interventions in the form of direct swallowing maneuvers, indirect environmental compensations, diet modification or advice on safer eating practices. In addition, such treatments may include instrumental support to monitor patients progress, but the impact of these techniques or programs of treatment is largely unknown. In fact, limited data exists to support any of these techniques. A recent Cochrane review of swallowing therapy following acute stroke noted only a positive but insignificant trend toward benefit from swallowing therapy.21 Unfortunately, research to date has focused predominantly upon case studies and small case series. Few randomized trials of efficacy have been attempted. A recent prospective randomized controlled trial that has attempted to address these issues was performed by Carnaby

www . DCMS online . org

et al. This study was a pragmatic trial that evaluated routine (usual) swallowing care practice compared to two levels of standardized swallowing treatment.18 The standardized treatment groups received high and low intensity regimes consisting of behavioral interventions and diet modification. High intensity subjects were treated for a minimum of once a day, whereas low intensity subjects received treatment no less than 3 times a week. Of 3,227 potential stroke patients screened, 306 were recruited for this trial. Each subject was evaluated by a blinded outcome monitor and followed out to 6 months post stroke. The results of this trial revealed that standardized swallowing treatment significantly reduced medical and dietary complications when compared to the routine swallowing treatment practice at that hospital. In addition, intensity of therapy enhanced outcomes. Levels of chest infection, institutionalization, and subjects remaining non functional feeders were reduced within the two treatment arms. Patients within the treatment arms also received significantly more treatment sessions with greater duration of treatment during each session, but they were treated for a significantly less number of days, suggesting a potential efficacy benefit. While providing some promising data, this is but a single study. Without more large prospective studies with rigorous control over confounders, the issues surrounding efficacy and the utility of the various dysphagia treatments will remain largely unknown. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES) is a new treatment technique for the rehabilitation of impaired swallowing following stroke. To date, over 5,000 speech language pathologists in the USA have been trained to use this technique, and it continues to gain popularity as a treatment modality. This technique involves the application of a low level electrical current across the skin to excite nerve or muscle tissue during a functional task. In dysphagia rehabilitation, small stimulating electrodes are placed on the muscles of the throat to promote a muscle contraction associated with swallowing. The procedure is reported to help stroke patients regain their swallowing ability by promoting clinical swallow performance and functional oral intake.22, 23,24 Although commonly used in the area of physical therapy, the application of the NMES technique to the muscles of swallowing has raised much controversy. 25 One of the reasons for the perceived controversy is the large commercial publicity of the procedure compared to the small number of published studies reporting investigations of this treatment technique. Although most studies have reported seemingly positive results, many have been criticized for design flaws and threats to external validity.26, 27 In fact, data defining the exact procedure for the treatment, optimum positioning of the stimulating electrodes, role of the exercise accompanying the stimulation parameters, and criteria for patient selection is lacking. This paucity of data has reduced the ability of clinicians to define and systematically measure the potential benefits of this new technique.

Future Directions

To date, investigation in the area of dysphagia following stroke has focused upon describing the natural history and characteristics of swallowing impairment in this group. Small studies of clinical and physiologic outcome have demonstrated the potential value of single techniques, maneuvers and exercises. Few large scale programmatic studies have been undertaken to evaluate the longer term health benefits of these interventions. Recently, this research direction has included investigations into short term benefits achieved from resistance exercises paired with and without electrotherapeutic applications. Promising results from these studies are beginning to emerge but, as yet, remain inconclusive. This new direction appears to have considerable potential to influence both the overall outcome of stroke survivors and reduce the burden to patient, caregiver, and community.

Conclusion

Dysphagia following stroke is a significant public health issue. Early identification and effective management of this problem can improve outcome for many stroke sufferers. It is clear that methods for the screening, evaluation and treatment of dysphagia all require further research and refinement. Only through rigorous inquiry can the relative value and utility of the currently used techniques be determined. To achieve this objective, better designed multi-centered trials that include large enough samples to assess the benefit of longer term health outcomes in identified dysphagic stroke patients will need to be undertaken.

1. HRQ Evidence Report #8. Diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders (dysphagia) in acute stroke patients. Appendix B. Burden of illness of dysphagia and its complications in neurologic disease. AHCPR Publication 1999; 99:E024. ATLANTIS Study Investigators. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. JAMA. 1999;282:2019-2026. Audebert HJ, Rott MM, Eck T, Haberl RL. Systemic inflammatory response depends on initial stroke severity but is attenuated by successful thrombolysis. Stroke. 2004;35:21282133. Axelsson K, Asplund K, Norberg A, Alafuzoff I. Nutritional status in patients with acute stroke. Acta Med Scand. 1988; 224:217-224. Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, et al. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991; 337:1521-1526. Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, et al. Dysphagia after stroke: Incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005; 26:2756-2763. Smithard DG, ONeill PA, Park CL, Morris J. Complications and outcome after acute stroke: Does dysphagia matter? Stroke. 1996; 27:1200-1204. Smithard DG, ONeill PA, England RE, et al. The natural history of dysphagia following a stroke. Dysphagia. 1997; 12:188-193. Mann G, Hankey GJ, Cameron D. Swallowing function after Northeast Florida Medicine Vol. 58, No. 2 2007 33

References

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

www . DCMS online . org

stroke: prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke. 1999; 30:744-748. 10. Duncan, P. W., Zorowitz, R., Bates, B. Management of adult stroke rehabilitation care: A clinical practice guideline. Stroke. 2005; 36:100-143. 11. Mann GM, Hankey GJ, Cameron D. Swallowing disorders following acute stroke: Prevalence and diagnostic accuracy. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2000; 10:380-386. 12. Ramsey D, Smithard D.G., Kalra L. Early assessments of dysphagia and aspiration risk in acute stroke patients. Stroke. 2003,34 (5)1252-7. 13. Martino R, Pron, G, Diamant, N. Screening for oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke: Insufficient evidence for guidelines. Dysphagia. 2000; 15:19-30. 14. Stoeckli SJ, Huisman TAGM, Seifert B, Martin-Harris BJW. Interrater reliability of videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation. Dysphagia. 2003; 18:53-57. 15. Martino R, Pron G, Diamant N. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: Surveying practice patterns of the speech-language pathologist. Dysphagia. 2004; 19:165-176. 16. Mann G. The Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability: MASA. Philadelphia: Delmar Thompson Learning. 2002. 17. OLoughlin G. Able to eat no mean feat- Dysphagia outcomes in stroke patients. Australian Resource Center for Healthcare Innovations [ARCHI] 2006. http://.archi.net.au/e-libruary/ health_administration/awards06/effectiveness. 18. Carnaby G, Hankey GJ, Pizzi J. Behavioral intervention for dysphagia in acute stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5:31-37. 19. Joint Commission on Accreditation of healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) The Stroke Performance Measurement Implementation Guide. 2005; 25 (6)3-6. 20. Hinchey JA, Shephard, T, Furie K, et al. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005; 36(9):1972-1976. 21. Bath PMW, Bath-Hextall FJ, Smithard DG Interventions for dysphagia in acute stroke. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000;(2):CD000323. 22. Blumenfeld L, Hahn Y, Lepage A, et al. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation versus traditional dysphagia therapy: a nonconcurrent cohort study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006; 135:754-757. 23. Shaw GY, Sechtem PR, Searl J, et al. Transcutaneous neuromuscular electrical stimulation (VitalStim) curative therapy for severe dysphagia: myth or reality? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007; 116:36-44. 24. Crary MA, Carnaby-Mann GD, Faunce A. Electrical stimulation therapy for dysphagia: Descriptive results of two surveys. Dysphagia. 2007 e- publication. 25. Logemann JA. The effects of VitalStim on clinical research thinking in dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2007; 22:11-12. 26. Ludlow CL, Humbert I, Saxon K, et al. Effects of surface electrical stimulation both at rest and during swallowing in chronic pharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2007;22:1-10. 27. Suiter DM, Leder SB, Ruark JL. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on submental muscle activity. Dysphagia 2006; 21:56-60.

34 Vol. 58, No. 2 2007 Northeast Florida Medicine

www . DCMS online . org

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 5 PBDocument10 pages5 PBKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- National Descriptors Texture Modification AdultsDocument21 pagesNational Descriptors Texture Modification AdultsKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- 07-3 Biopiracy Imitations Not InnovationsDocument76 pages07-3 Biopiracy Imitations Not InnovationsKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery: Module MenuDocument5 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery: Module MenuKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

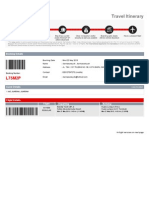

- Travel Itinerary: Booking DetailsDocument5 pagesTravel Itinerary: Booking DetailsKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Family+MedicineDocument23 pages2 Family+MedicineKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1principlesof FMDocument26 pages1principlesof FMKhairul MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Logical SpatiallDocument130 pagesLogical SpatiallRoy C. DomantayPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL Carpentry Second QuarterDocument6 pagesDLL Carpentry Second QuarterJenny Mae Lucas Felipe80% (5)

- Emg20 Q1 OtDocument6 pagesEmg20 Q1 OtChua KimberlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Consensual Qualitative Research: The Theory: Diosdado M. San Antonio 21 December 2016Document30 pagesConsensual Qualitative Research: The Theory: Diosdado M. San Antonio 21 December 2016Cyn DrylPas encore d'évaluation

- Wlce Answer Key PDFDocument30 pagesWlce Answer Key PDFMarie Michelle Dellatan LaspiñasPas encore d'évaluation

- Template - Research 1 Learnring Module 1Document31 pagesTemplate - Research 1 Learnring Module 1Rey GiansayPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review of Assessing Student LearningDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Assessing Student Learningapi-283267030Pas encore d'évaluation

- Filipino Trait and Personality Church and KatigbakDocument12 pagesFilipino Trait and Personality Church and KatigbakMimiSnow100% (1)

- RSM7204 - Course Outline - Summer 2022Document8 pagesRSM7204 - Course Outline - Summer 2022Aman DattaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 1 Case Investigation ReportDocument3 pagesAssessment 1 Case Investigation Reportsaqer_11Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge English Scale FactsheetDocument2 pagesCambridge English Scale FactsheetEdwin DavisPas encore d'évaluation

- PHL 101 SampleDocument17 pagesPHL 101 Samplelyrah_eb425100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Listening Speaking and Pronunciation FINAL ROSMERYDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Listening Speaking and Pronunciation FINAL ROSMERYRosmery RiberaPas encore d'évaluation

- CEP Diagrama Causa-Efecto (Ingles)Document35 pagesCEP Diagrama Causa-Efecto (Ingles)Roftell RamírezPas encore d'évaluation

- C1 Advanced Exam Format - Cambridge EnglishDocument3 pagesC1 Advanced Exam Format - Cambridge EnglishMichele DalfovoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ratiba Ya NECTA Kidato Cha Nne 2015Document5 pagesRatiba Ya NECTA Kidato Cha Nne 2015DennisEudesPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Comprehension & Executive Functioning A Meta Analysis Ed Psy 2018Document20 pagesReading Comprehension & Executive Functioning A Meta Analysis Ed Psy 2018Anne CunninghamPas encore d'évaluation

- Q4 Applied Eapp WK5Document4 pagesQ4 Applied Eapp WK5Jomarie LagosPas encore d'évaluation

- Neoreviews 1.11Document79 pagesNeoreviews 1.11Ridzuan HarunPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 William Edwards Deming Power PointDocument21 pages9 William Edwards Deming Power PointTArek SArkerPas encore d'évaluation

- 4TH Quarter-Tle 7 Lesson PlanDocument13 pages4TH Quarter-Tle 7 Lesson PlanChristy Parinasan100% (2)

- 4A07 Nguyen Thi Xuan Mai English and Vietnamese ConsonantsDocument18 pages4A07 Nguyen Thi Xuan Mai English and Vietnamese Consonantsnbt411Pas encore d'évaluation

- CaddraGuidelines2011 ToolkitDocument48 pagesCaddraGuidelines2011 ToolkitYet Barreda BasbasPas encore d'évaluation

- Format For Course Curriculum: Software Testing Course Level: UGDocument4 pagesFormat For Course Curriculum: Software Testing Course Level: UGSaurabh SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Model Curriculum Diploma Civil Engineering 310812Document66 pagesModel Curriculum Diploma Civil Engineering 310812Aravind KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Practicing For The: TerranovaDocument34 pagesPracticing For The: TerranovaTatiana Shivchenco100% (1)

- Brief Guide To Competency-Based InterviewsDocument3 pagesBrief Guide To Competency-Based InterviewsАне ДанаиловскаPas encore d'évaluation

- PRELIMS - Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument4 pagesPRELIMS - Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonAndrey CabuntocanPas encore d'évaluation

- Adv. No. 1of 2022Document9 pagesAdv. No. 1of 2022CHIRANJIBI BEHERAPas encore d'évaluation

- RES 721 - Syllabus - Creswell & Creswell (5th Ed.)Document26 pagesRES 721 - Syllabus - Creswell & Creswell (5th Ed.)aksPas encore d'évaluation