Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

India's North-East States

Transféré par

Sunny ChohanTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

India's North-East States

Transféré par

Sunny ChohanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Indias North-East States: Narcotics, Small Arms and Misgovernance

Mahendra P Lama

Abstract

The seven states of India's north-east, located on or close to the border with Bangladesh, China, Myanmar and Nepal have all had a history of prolonged troubles. Among the more disturbing aspects are the narcotics trade in the region, insurgency and trafficking in arms. The number of drug addicts has kept increasing at an alarming rate. This is partly the result of the proximity to Myanmar, now the world's principal heroin producer. Almost every state in the north-east is affected by insurgent activities, and many parts of the region have been declared "disturbed areas" under the Armed Forms (Special Powers) Act of 1958. An array of insurgent outfits has developed has in recent times, working in close co-ordination with each other within and outside the north-east. A large quantity of modern and sophisticated small arms including AK 47s and M16s are in circulation in the region and generally in the hands of these insurgents. The central government has adopted two policies in response to these problems. One of these is the creation of more states all of them small in area. Secondly, a large amount of funds has been pumped into the region. Neither of these has been very successful in coping with the problems there.

I Introduction

The states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura (with Sikkim, included in 1975), in Indias north-east are on the border with Bangladesh, China, Myanmar, and Nepal. These states are a troubled legacy for India. Although their varied and rich natural resource endowments could provide the basis for rapid economic growth, this has not happened. Nevertheless these states have much better social indicators than many states in other parts of India. Many of the states of Indias north-east were given full-fledged statehood generally after prolonged agitation and all of them have actively participated in the entire democratic process conducted both at the state and local levels for this purpose (Table 1). In response to prolonged trouble in many of these states, a huge amount of funds has been pumped into them during the last five decades by the Union government regardless of the size of the state and its population. The basic idea has been to wean the population away from insurgent activities and to provide opportunities for such activists to return to a normal life, including political participation. This present chapter deals with one of most disturbing aspects of life in many of these states, the problems of the narcotics trade in the region, and its links with insurgency and trafficking in arms. As we shall see these trades make such a return to a normal life style much more difficult, if not virtually impossible, unless more systematic measures, than have hitherto been taken, are devised and put into effect.

Ethnic Studies Report, Vol. XIX, No. 2, July 2001 ICES

244

Lama

Table 1 North-East States: Population, Per Capita Income and Illiteracy Rate

States Full-fledged Statehood 1987 1947 1972 1972 1987 1963 1975 1972 Population (million) 0.864 22.41 1.83 1.77 0.689 1.20 0.406 2.75 Per Capita Income (US $) (*) 250 171 153 175 215 190 164 121 Illiteracy (%) 58 47 40 50 17 38 43 39

Arunachal Pradesh Assam Manipur Meghalaya Mizoram Nagaland Sikkim Tripura

Source: (*) Computed from Per Capita Income (Rs), Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey, 1996-97, Government of India.

There are a number of indicative parameters to show how poor governance of the state is related to drug abuse and other consequential problems. In north-east India, abuse of alcohol, opium and cannabis has been common from time immemorial. Ganja (marijuana) is also very popular particularly in the rural areas. What is even more important is the remarkable change in the form of narcotics consumed and in the nature of the people affected by the abuse of such items in recent times. The commonly known inexpensive traditional alcohol and ganja have been steadily replaced by more expensive and not easily accessible items such as heroin commonly known as number 4 in the drug addicts' parlance.1 The use of heroin has outstripped all other forms of drug abuse. And drug abuse which used to be the bane of the urban, middle class and affluent sections of society has moved beyond them to the poor and rural youth across the region. It is clear that the resources allocated for both plan and non-plan expenditures have not been utilised for the purposes they were allocated for. Even if they were targeted to objectives such as poverty alleviation, public distribution system, health, education, drinking water and rural electrification, these resources either did not reach the target groups or had a huge leakage in the delivery mechanism.2 In the absence of any monitoring and evaluation of these projects and related use of resources, the leakage and diversion of funds became a regular feature and gradually became institutionalised. Meanwhile, the resources kept coming in from Delhi regardless of how they were utilised. This continuous flow of resources in fact did consolidate the emerging institutionalised corruption. The issue is how and where to use the money amassed through corruption. It is a common feature in north-east India that the earning of money is quickly reflected in the apparent consumption patterns of the people, and also in buildings, and cars and modern gadgets at home. More dangerously, it is reflected in the behaviour of the youth who have very limited entertainment options in the region. Since most of them would hesitate to go out of the state, they would like this easy money to be spent in the cities and towns of their own state. And one very fashionable way is to resort to expensive narcotics. Once they are in the chain of drug abusers it is then very difficult for them to get disentangled and so the process continues from a resort to anti-social activities and, often on to insurgency. Despite so much pumping of resources to the area, most of the states in the north-east continue to remain in a state of poverty. Though the percentage of population below the poverty line has gone down steadily during the 20 years from 1973-74 to 1993-94, the numbers in absolute terms have in fact increased. For example, in small states like Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya the percentage of people living below the poverty line has come down steadily from 51.93 to 39.35% and from 50.2 to

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 245

37.92 respectively during the period from 1973-74 to 1993-94, but the actual number of people below the poverty line has increased from 2.66 lakhs to 3.73 lakhs and from 5.52 lakhs to 7.73 lakhs respectively during the same period. Indeed the total number of persons below the poverty line in the entire north east region (including Sikkim) has increased from 10.9 million in 1973-74 to 13.49 million in 1993-94. This means 4.2% (3.39% in 1973-74) of the people below the poverty line in India is concentrated in a land area of 7.97% of the country (Table 2). Moreover, the concentration of the people below the poverty line in the rural areas goes to show that the rural development programmes, particularly the poverty alleviation measures, have not really benefited the rural poor.

Table 2 Number and Percentage of Population below Poverty Line by States 1973-74 (Modified expert Group)

States 1973-74 % of No. of persons persons (lakh) (2) (1) 2.66 51.93 81.83 51.21 5.36 49.98 5.52 50.2 1.82 50.32 2.9 50.81 1.18 50.86 8.54 51 3213.36 54.68 1983 1993-94

(1) 2.82 77.69 5.65 5.62 1.96 3.5 1.35 8.95 3228.97

(2) 40.88 20.47 37.02 38.81 36 39.25 39.71 40.03 44.48

(1) 3.73 96.36 6.8 7.38 1.94 5.05 1.84 11.79 3203.68

(2) 39.35 40.86 33.72 37.92 25.66 37.92 41.43 39.01 35.97

Arunachal Pradesh Assam Manipur Meghalaya Mizoram Nagaland Sikkim Tripura All India

Source: Government of India, Perspective Planning Division, Planning Commission, Report of the Expert Group on Estimation of Proportion and Number of Poor, Government Press Faridabad, 1993.

In the absence of reliable income distribution data, one can only check the equality/ inequality of income distribution through indices such as the per capita ranking, per capita income growth rate and poverty estimates. While per capita rankings of the north-east states have generally gone up over the years, their poverty ranking has gone down sharply. For example, out of the 25 states in the country, Nagaland had the 9th highest per capita income and ranked 13th in the measurement of poverty among the states in 1983-84. By the years 1993-94, though its per capita ranking remained unchanged at the 9th position, its poverty ranking slid down to 9th position. This means that in 198384, Nagaland was better than 12 states in the country in poverty management but this deteriorated to the point where it was better than only 8 states in the percentage of people living below the poverty line in 1993-94. Similarly, Sikkim had the 12th highest per capita income in the country and it also ranked in the 12th position as far as the people below the poverty line were concerned in 1983-84. Over the years, it has been able to improve its per capita income ranking to the 10th position, whereas its ranking in the poverty status has gone down very sharply to 4th position. Sikkim is thus the 4th most poverty-ridden state in the country today which is a worse position than all the north-eastern states and only better than Bihar and Orissa (Table 3). This situation could be interpreted in very many ways. For one thing the high per capita income vis--vis a very high poverty status implies that the income is very skewedly distributed in the state. This means that the top echelons of society may be getting an overwhelmingly high percentage of the share of the income, indicating thereby a significant concentration of income. This has been so for many of the states in the north-east. Secondly, since most of the poverty-stricken people are concentrated in the rural areas, it could also mean an increasing urban-rural gap in terms of both

246

Lama

distribution of income and asset creation. This will in the long run go against environmental security and sustainability of the state and this syndrome of income concentration also indicates the deviation in the fundamental principles and objectives of governance and the management of the economy wherein the guiding philosophy should have been to distribute the national wealth across the state in an increasingly equitable manner. A noted economist of the region Jayanta Madhab points out that the credit-deposit ratio being very low in the region, the banking sector transfers something like Rs 5,000 crore from this region to other regions for investment. Because of prolonged insurgency in the region, despite abundance of natural resources (oil, gas, coal, granite, limestone, water and forest wealth) no outside investment has taken place. Indeed, there was capital flight in the last eight years from the region.3

Table 3 Ranking of the North-East States in Terms of Per Capita Net State Domestic Product at Current Price (Rs)

1983-84* Per capita Poverty Rank Rank (1) (2) 8 6 9 19 16 16 14 18 17 22 13 9 12 12 11 24 1987-88 (1) 8 19 12 16 6 10 7 22 (2) 8 9 17 14 18 13 10 11 1993-94 (1) 7 19 18 17 11 9 10 24 (2) 7 5 13 9 17 9 4 8

Arunachal Pradesh Assam Manipur Meghalaya Mizoram Nagaland Sikkim Tripura

* Out of 25 states Notes: Per capita income rank is in the ascending order i.e. Arunachal Pradeshs per capita income was the 6th highest in the country in 1983-84. Poverty ranking is on the basis of descending order (from the highest to the lowest) i.e. Arunachal Pradeshs position in the list of people below poverty line was 8th in 1983-84.

Both these persisting syndromes of poverty and skewed distribution of income have played a very critical role in shaping the future of youths in these states. This has a far reaching consequence in the increasing number of unemployed people in these states and a generation of frustrated youth. In fact, a study done by the Ministry of Welfare in 1989 found that 88% of the sampled drug addicts in Guwahati cited frustration as the reason for them to go for drugs.4 Given their history of poor inter-state mobility particularly to regions other than the north-east, these poverty-stricken and unemployed youths have tended to resort to various activities which give them a quick income and some measure of instant, if temporary, success. And in most cases these activities relate to drug trafficking and abuse, arms and bootlegging and other smuggling activities. This is further encouraged by the immunity provided by local political leaders to such youth, for their ownthe leaderspetty political gain. In the process youths become the instant prey of forces inimical both to society and the country. A large number of them have either joined insurgency movements or newer forces like the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) or are in the pay of foreign agencies such as the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan. Thirdly, the poor governance of the states has led to two very significant consequences. Corruption has been rampant and at times blatant. Accountability has been totally absent in many of the states. This has led to exploitation and manipulation of these corrupt officials by the militants, and near anarchy in some places particularly in regard to the maintenance of law and order, a major factor

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 247

in the forced support to the insurgent groups extended by some very well known private agencies. All of this constitutes the second stage of the chaotic situation that has developed in many of these states. Initially certain state actions including inappropriate economic intervention, unsuitable political policy intervention, and the resulting protracted confrontation with insurgents, and between them and the security forces both at the Union and the state level, created huge problems. The situation becomes more complex when in order to sustain their operations, the insurgents go in for sophisticated weaponry. This in turn prolongs the conflict, and brings instability to the system apart from weakening the sinews of state controls particularly in the law and order area. When the state fails to protect the general population particularly those with economic power, the latter tends to organise their own security system sometimes by succumbing easily to the financial and other demands of the insurgents. This more often institutionalises friendly extortion, but goes directly against the state as it literally gets side-tracked in the business of running an administration. Here the role and grip of the state over certain administrative areas like law and order maintenance gets vastly eroded. This is what has been happening in the north-east. The most vital examples are the business community and industrialists including those in tea, jute and timber, indirectly and tacitly supporting the insurgent activities by providing them with money under pressure on friendly terms or otherwise. A very crucial example is that of the Tata Tea Companys case of 1997. Tata Tea is one of the Indian giants and has a huge stake in the tea industry of Assam. The Tata Tea and five other unnamed companies were found to be providing funds to the militants, particularly the ULFA. In a statement made in September 1997, Prafulla Mahanta, chief minister of Assam, stated that:

It is not that we are singling out the tea industry. Investigations are also on to ascertain which other companies, both in public and private sectors have paid the extremist groups and action will be taken against those found guilty... an inquiry has been initiated against government employees who were allegedly funding the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB), formerly the Boro security force. The audited financial accounts of the NDFB for 1994-95 and 1995-96 revealed the outfit received money for sales tax, forest and motor vehicle inspectors.5

Most of the plantations have had to part with some cash for the necessity of ensuring protection to tea garden managers or members of their families who would naturally be the first targets of attack from the ultras said a spokesman for the Tea Company.6 Fourthly, across the international border vigilance is poor and there are symptoms of loose national controls because of weak administration. So extraterritorial forces including some from Myanmar and Pakistans ISI play a major role. Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh have a long international border with unguarded and rugged border points. The smugglers exploit these factors. They have a preference for the heroin produced in the Golden Triangle (Laos, Myanmar and Thailand) as they find the purity content of heroin from it to be as high as 90 to 95%, whereas the purity content is hardly 40% in heroin from the Golden Crescent. A Delhi-based newsmagazine mentions that according to an US intelligence report on the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka, the sea route from the Golden Triangle to Myanmar is a key conduit for arms and narcotics. A very substantial percentage of the heroin in the world market is channelled through this route.7 The Bangladesh connection of some of the militants is very well known. Clinching evidence of this was the arrest of ULFA leader Anup Chetia in Dhaka. In fact, a booklet published by the Ministry of Home Affairs pointed out that:

ULFA has reportedly started several income generating projects in Dhaka, Mymensingh, Narsingdi, Sylhet etc. which are run by money partly received as subscription from tea gardens in Assam and partly by donor agencies.... In Dhaka, ULFA owns three hotels, a

248

Lama

private clinic, two motor driving schools. In Sylhet, it has a number of grocery shops and drug stores. In Mymensingh, it owns some poultry farms while in Narsingdi, it runs two schools.8

This Myanmar connection in the arms supplies to the north-east became so serious that in 1995, the Indian and Myanmarese armies conducted a joint operation known as Operation Golden Bird on the Manipur-Myanmar border where at least 40 insurgents were killed. The commander of an counter-insurgency army corps stated later that the militants in the north-east and Myanmar actively aided by the Pakistani ISI are getting their arms supply from the flourishing arms market in the Far East.9

II Trafficking and Trade Routes: A Complex Chain

The illicit drug trade is a highly sophisticated operation with clearly defined interests, strategies and aims with a unified power structure, and with total control over the whole process including a complex chain of small businesses. Activities are carried out by many individuals, independent and intermediate traders, who, however, often indulged in violent rivalries as much as they did in coordination. The drug trade has different stages ranging from primary production where farmergrowers are involved, to secondary production where the persons and intermediaries with the knowhow required to convert the base into processed drugs are involved and on to the transport and distribution and consumption stage where the so-called cartels have the appropriate infrastructure to facilitate transport and distribution of the drug. This infrastructure consists of a network including transit areas.10 The major outflows in the north-west into India are from Sagaing to Tamu to Manipur, and Kalay/Tiddim to Mizoram. From the main unit producing heroin at Kalaymyo, under the control of a businessman who works with well-known drug traffickers from north-west Myanmar as well as the army, there are three major routes: to the north towards Khampat and Tamu-Moreh and from there to Imphal; to the west towards Rikhawdar/ Champhai and from there to Aizawal; and to the south-west include: from Khamti areas through Noklok to Mogokchung in Nagaland; from Tamanthi and Homalin to Somra and from there northwards through Jessami to Kohima in Nagaland; and from Paletwa to Alikadam in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh, to Coxs Bazaar and Chittagong. Some heroin is also trafficked over the Arakan state border into Bangladesh, then trafficked again to India.11 In Myanmar, there are persistent reports from Chin state and Sagaing division, of the authorities collusion in both production and transportation of opium and heroin. These are transported down from Shan state to the Indian border, then into neighbouring countries and on to the world market. Drugs coming from Myanmar into Manipur are mostly sent to Patna, one of the major drug centres in India, and on to three other distribution points: Kathmandu, Delhi and Bombay. From there, they are further trafficked on to the international market, now overwhelmingly reliant on people from Myanmar. The effects of this trade are felt not only in Asia, but all over the world.

Estimates of Trafficking

Myanmar is now the worlds principal heroin-producer and heroin is frequently described as the most valuable export of the country. For that country, the official economy offers few alternatives to the heroin trade.12 Since the SLORC seized power in 1988, the production of opium, from which heroin is refined, has risen to over 2,030 metric tons annually, amounting to 60% of the world supply.13 Of the supply to North American and Australian markets, heroin from Myanmar accounts for 57% and 76% respectively. While previously most of the heroin reaching Europe originated in the Golden Crescent (Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran) reportedly, over the past two years, a growing portion of the European heroin market is also being supplied by Myanmar, with heroin trafficked out of northwestern Myanmar.14

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 249

In Myanmar, Shan state has been the centre of opium production and conversion. All this is dispatched to plains around Mandalay, through Chin state and Sagaing division and into northern India and onto world markets. This is so despite the claims by the military junta that they are actively combating drug production and distribution. In fact there has been a massive increase in poppy cultivation after they came under the control of the military regime. It is also alleged that high-level government and military authorities have increasingly profited from the narcotics trade by taking bribes for not sending troops into areas where refineries are located.15 Table 4

The major points of trafficking are: Moreh (Manipur): About 109kms south-east of Imphal on the Indo-Myanmar road (national highway no. 39) with a population of over 25,000. Tribals like Kuki-Chin, Meitis and Mizos are in a majority and the other inhabitants are Tamils and Punjabis. Moreh is also a flourishing border trade point. The 12 April 1995 agreement between the governments of India and Myanmar allows the trade through Moreh and Tamu and Champhai (Mizoram) and Hri (Myanmar). Though the cross border trade supposedly includes only locally produced commodities and other produce of the respective countries, the composition has undergone drastic change with more trading on non-traditional high value items including electronics and drugs. Tamu (Myanmar): A counterpart border town located in Myanmar. There has been literally a free movement of people and goods between these towns. This is the town which regularly exports Chinese and other foreign goods to the north-eastern states. Nagaland: four major routes TamuImphalDimapur (surface route) Pangsa (Tuensang district)Noklak-Kiphire-KohimaDimapur (surface route) JhizamiPfutseroKohimaDimapur (surface route) TirapLedoDimapur (railway route) Other routes Behiang-Singghat-Churachandpur-Tipaimikh-Silchar in Assam; Mandalay-Tahang (both in Myanmar), Homalin (Myanmar)-Ukhurul (Manipour)-Jessami-Kohima (both in Nagaland); Mandalay-Tahang (Myanmar border)-Aizwal-Silchar; Homalin-Kamjong (Manipur border town)-Shangshak Khullen-Ukhriul; Myitkina-Maingkwan-Pangsau Pass (thick forests in Myanmar) Nampong-Jairangpur-Digboi (upper Assam); Putao (Hkamti area of upper Myanmar)-Digboi-Pasighat (in Arunachal Pradesh-other destination) and Tamanthi (Myanmar)-Noklak (Nagaland border with Myanmar)-Kohima-Dimapur New Somtal (in Chandel district)-Sugnu-Churachandpur-Imphal Kohima-Dimapur and Kheinan-Behiang-Churachandpur-Imphal-Kohima -Dimapur.

According to the Geopolitical Drug Dispatch:

... heroin laboratories and drug-export routes have now shifted to the south-west [from Kachin state and the Chinese border]. Major drug-production units are now operating along the Chindwin river near the Indian border, under direct protection by the Burmese army, far from zones controlled by the rebels and from the notorious Golden Triangle... (In 1992) rather than heading up to the Chinese border, trucks loaded with raw opium and heroin began heading down the central plain to the south around Mandalay. Shortly afterward, other sources in India reported that the north-east regions of Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram were flooded with heroin.16

There are varying estimates of the extent of drug trafficking in the region. Some of the states adamantly deny any such incidents of drug import or trafficking while some states do agree partially. However, in the absence of any reliable source of information, the estimates vary a lot.

250

Lama

A study done by the Ministry of Welfare, government of India, shows that in Dimapur alone 5.614kgs of heroin, 679kgs of ganja, 1kg of opium were seized during a brief period in 1986-89.17 An official report prepared in August 1989, as quoted by P Tarapot, stated that Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland together accounted for the smuggling of at least 20kgs of heroin every day both for the local illicit markets and other national and international destinations in 1989.18 The following are the figures indicating the seizures of heroin by the Nagaland police and State Excise Department during a three year period.

Table 5 Year 1992 1993 1994 TOTAL Nagaland Police 3.957 kgs .613 kgs .260 kgs 4.830 kgs Nagaland Excise 1.450 kgs .288 kgs .008 kgs 1.746 kgs

Source: Police Department, Government of Nagaland, Kohima.

III Narcotics-Small Arms Linkage

Though the cascading phenomenon wherein the initial supplies have been controlled or funnelled through state (mostly intelligence) agencies to arm non-state actors and groups,19 has not come to light in the north east region, there has been a massive interplay of both criminal and insurgent activities with a substantial arms base. The detection of exact linkage is further constrained by the absence of necessary databases, automation, communications and collection management necessary to improve the intelligence contribution. With the intent of developing pre-movement tactical information, detection and monitoring mission must be emphasised early by identifying the overall structure that led to the movement of narcotics. However, this has been true equally of other countries more seriously affected by drug trafficking. J F Holden-Rhodes mentions that one of the most difficult and continuing problems was the lack of a database to support the analysis effort. Initially, it was thought that the necessary information was held in law enforcement community files. Early examination revealed that the data contained material on US citizens which made receiving and storing it in the DIA an illegal act.20 Almost every state in the north-east is affected by insurgent activities. Many parts of the northeast have been declared as disturbed areas under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958.21 There is an array of insurgent outfits, many of whom have emerged very recently. Table 6 gives us a brief idea about various insurgent groups and terrorist organisations operating in the region. There are a number of common features among these groups, beginning with their varied political demands starting from statehood within the constitution of India to re-demarcation of interstate borders to the expulsion of foreigners and outsiders. A number of them are fighting against the Union of India and have been demanding secession from the Indian Union, some of them since preindependence times. Since most of them are well equipped in sophisticated weaponry they seldom hesitate to resort to violence particularly against the state armed forces. This violence is sometimes extended also against a particular community or a group leading to arson, destruction and mass killings.

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 251

252

Lama

Table 6

Arunachal Pradesh United Peoples Volunteers of Arunachal Pradesh (UPUA) United Liberation Volunteers of Arunachal Pradesh (ULVA) United Liberation Movement of Arunachal Pradesh (ULFA) Assam United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA): Strength 1,600 militants, 200 AK series rifles, 20 RPGs and 400 other types of rifles Bodo Security Force (BSF) Karbi National Volunteers (KNV) Adam Sena National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB): Strength 600 militants, 50 AK series rifles and 100 other types of rifles Muslim Security Force (MSF) Muslim United Liberation Tigers of Assam (MULTA) Islamic Tigers Muslim Volunteers Force (MVF) Sadam Bahini Bodo Liberation Tiger (BLT) Manipur United Nationalist Liberation Front (UNLF): Strength 1,500 militants and 200 AK series rifles Kanglei Yawol Kanna Lup (KYKL) Peoples Liberation Army (PLA): Strength 1,000 militants and 150 AK series rifles Peoples Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) Kuki National Front (KNF) Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP) Islamic Liberation Front (ILF) Hmar Peoples Convention (HPC) Kuki National Party (KNP)

Meghalaya Achik National Volunteer Council (ANVC) Hynniewtrept Volunteers Council (HVC) Achik Liberation Matgrik Army (ALMA) Nagaland National Socialist Council of Nagaland [Isaac-Muivah (NSCN-IM)]: Strength 2,000 militants, 400 AK series rifles, 50 RPGs and assorted rifles National Socialist Council of Nagaland [Khaplang (NSCN-KM)]: Strength 1,000 militants and 200 AK series rifles Cotd..

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 253

Table 6 contd.. Tripura Tripura National Force (TNF) National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT): Strength 150 militants and 50 AK series rifles Tripura Commando Force (TCF) National Militia of Tripurs (NMT) All Tripura Volunteer Force (ATVF) All Tripura Tiger Force (ATTF): Strength 200 militants and 50 AK series rifles Tripura and Tribal Commando Force (TTCF)

Many of these groups are said to have been working in close co-ordination with each other within and outside the north-east. A more notable phenomenon is their links with extraterritorial forces including China and the ISI of Pakistan. The leadership of many of these outfits is known but untraceable as they are stationed outside India, in Bangladesh, Bhutan and Thailand. Many of them have resorted to large scale extraction of money from both the government and private agencies. Some of them have even been practising what they call tax collection. Most of them have been boycotting all the regular democratic processes in the respective states including the state assembly and general elections. There are quite a few of them who have come over-ground and participated in the negotiating process. Some have even surrendered and thereafter joined mainstream political movements. There is a large quantity of modern and sophisticated small arms including AK47s and M16s in circulation in the north-east region, and generally in the hands of these insurgent groups and other non-state actors. Many believe that unless these insurgent groups resort to smuggling and drug trafficking, they could not have mobilised resources for purchase of weapons and maintenance of their cadres. The other possible sources could be extortion or supply by inimical foreign agencies. In order to substantiate this latter contention examples are provided of the links between extraterritorial forces and insurgent groups. As a Times of India report indicated ULFA received arms training from Kachin Liberation Army which operates from Myanmar and later from both factions of NSCN. They have been in contact with the Bangladeshi army, Pakistans ISI and the LTTE.22 But since these activities have been sustained for so many years with a lot of vicissitudes in the material situation, the major role of these external sources in funding the insurgents could be largely discounted. It is believed that a subnationalist movement led by the ULFA gets at least 10-15% of its funds from the illegal narcotics trade.23 In fact, many of the prominent insurgent groups such as UNLF, NSCN and PLA have been vociferously campaigning against the drug addicts and the drug traffickers particularly in Manipur and Nagaland. It was the PLA which imposed prohibition (banning sale of liquor) in January 1990, with the government announcing the prohibition immediately after.

Their anti-drug campaign appears to be serious because they have been shooting hundreds of drug addicts and peddlers in the region in the recent years. The UNLF and PLA would first warn the addicts, peddlers and traffickers to give up consumption or selling it. If their warning is ignored, the extremists would shoot them below the thigh or in the leg. The underground activists published names of drug addicts or the peddlers soon after they had punished them. Their intelligence network, monitoring of persons who took heroin or sold the narcotics was far better than that of the government agencies... In fact, there has been a mass movement against drug addiction and alcoholism in the region particularly in Manipur and Nagaland... The drive launched against these social evils by underground activists was more effective than those adopted by other agencies. The armed extremists would enter the house of drug addicts or peddlers and explain to them the worst effect drug addiction or alcoholism would have on society and warn them not to take narcotics. The extremists even threatened parents if they did not keep their addicted children either at drug de-addiction

254

Lama

centres or in jails. If the underground warnings were not heeded the extremists would punish them by shooting them.24

In the north-eastern region, arrests of local drug dealers are not very common or frequent. There has been occasional bursts of activity such as when several small packets of heroin (reported in local newspapers) were seized in Mizoram and the border was temporarily closed on the Mizoram side. Thereafter it was a return to normal. Likewise, arrests at the Myanmar border town of Tamu are not very common, even though Tamu is a major transhipment point. In geographical areas where the presence of drug traffickers and terrorists coincided, a convergence of interests occurred for the purpose of confronting a common enemy, which was the state.25 However, the Indian policy of neutrality in the case of Myanmar affairs, has so far kept terrorism and drug trafficking as two separate phenomena in the region. The other part of the story is quite damning. The armsrunning through the sea off the Andamans to the north-east has come to light in recent years. Apparently many of these illegal arms consignments including AK series rifles, rocket propelled grenades, night vision fitted rifles and hand grenades originating in the Far East, were meant to go to the Myanmar rebels fighting the military regime in Yangon, but are increasingly being diverted to insurgent groups in the north east including the ULFA and the NSCN. All these arms are brought to Coxs Bazaar in Bangladesh and consignments are broken up into small caches to be carried by three different routes. A part of it goes to the Chin rebels and the rest to the north-east. This has largely gone against the counter-insurgency operations in the north-east for which over 25,000 troops are deployed at a maintenance cost close to Rs 100 crore a year. The importance of this arms-import-route was confirmed by the successful tri-service interception named Operation Leech on the high seas off the Andamans conducted in February 1998. In that operation, security forces killed six gun-runners, arrested 73 others and seized a huge consignment of arms, including 140 AK47 series rifles and assorted ammunition. The end users of this particular consignment were mainly three major groups two in the north-east and one in Myanmar the banned NSCN, the All Tripura Tiger Force (ATTF) and the Chin National Army in Myanmar.26 The narcotics and illegal arms import connections were confirmed again in May 1998, when defence forces intercepted two more Thai trawlers near Narcodam island and seized a 50kg consignment of heroin along with an unspecified number of guns and assorted weapons.27 In fact, much of this heroin was meant for European and American destinations which prompted the Narcotics Control Bureau of the USA to seek support from the Defence Services headquarters to check the flow of narcotics.28 The Bhutan-Nepal area is also fast emerging as another route for the illegal trafficking of narcotics; this is confirmed by a number of big seizures in the recent past. It includes 5.25kg of cannabis seized by the Bhutanese police from the Bhutanese who were working for a Nepal-based gang in Phuentsholing.29

IV Implications

All these issues have wide political, economic, military, health, environmental and psychological consequences that pose threats to Indian sovereignty, and to the political stability, economic and social equilibrium of many of these states. Firstly, the number of drug addicts has been increasing at an alarming rate. The expenses involved often lead to heavy indebtedness, and this in turn to the selling of land and houses. Street violence and other social crimes have recorded a steep climb, although the traffickers and drug-baron led systematic violence have not been seen. In fact, some parents in the region often express the view that they would like their children to be sent to confinement and police custody for their own safety! The affected families and the governments now find that the problems of drug abuse are more serious than the decades of dreaded insurgency activities in these states.

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 255

Manipur jails have turned into reformation centres for drug addicts.30 Given this depressing scenario, a feeling that alcoholism is more tolerable than drug addiction is fast catching up in the north-east.31 On 2 October 1997, community organisations in Moreh, Manipur state, launched a week-long satyagraha or campaign of civil disobedience primarily against the menace of drugs and AIDS. The original aim of the campaign was for protesters to form a human wall along the border to stop heroin traffickers from entering, on the assumption that the place at which the problem needs to be tackled, is at the consumer end. The snag is that drugs are easy and cheap to produce. There is also the sense that addicts should not be treated as criminals. They should never be allowed unsupervised on the streets until their addiction is cured, because they will inevitably have to recruit more addicts in order to pay for the drugs they need for themselves.32 Secondly, in the areas faced with serious trafficking or local production problems, the pattern of HIV transmission among injecting-drug users (IDUs) is stark testimony to the so-called spillover effect.33 The number of HIV infected people has multiplied. The HIV positive among drug addicts is mostly by sharing of infected syringes while injecting heroin into their bodies. A survey showed that half of Manipurs estimated 25,000 drug users were infected with the AIDS virus between October 1989 and June 1990.34 According to a very recent survey referred to in the Times of India, 7,000 drug addicts (mostly intravenous drug takers) were subjected to various tests in Manipur alone. Of these, 4,000 were found to be HIV positive. These trends have also been confirmed by the World and South Asian Drug reports.35 The Churachandpur district in Manipur has been the worst hit area mainly because of its proximity to the Golden Triangle countries.36 The state government has now opened a Surveillance Centre for AIDS in the Regional Medical College in Imphal. According to Bertil Lintner, the state ...had 600 drug addicts in 1988. Two years later there were at least 15,000and the state also turned up more than 900 AIDS carriers, identified as heroin addicts who used common needles to inject the drug. Manipur, by 1992, had the highest incidence of drug-related AIDS infections in India, a state of only 1.2 million people.37 On a plea made by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MSJ&E), United Nations Drug Control Programme (UNDCP) has agreed to fund two projects of Rs 22 crore in the north-east to fight drug abuse and to protect, cure and rehabilitate the high risk groups through community involvement. Thirdly, the economic implications of the north-east being the host of drug addicts and its proximity to the drug-corridor are very serious. Apart from destroying some of the main pillars of the society, especially the youth, the corridor status has given the north east an artificially high cost economy. It might have an impact on agriculture as the arable land could be more profitable for the cultivation of poppies and marijuana. Though this has not been recorded in the north-east, this is widely so in many other drug-corridors in other parts of the world.38 It might also lead to a sharp fall in tourist traffic thereby badly affecting the entire services sector such as hotels and transport among others. Fourthly, government officials are increasingly falling prey to the attractions of links with insurgent groups. The document entitled Bleeding Assam published by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs accuses Assam government employees of being in association with the banned ULFA. It mentions another modus operandi (adopted by the ULFA is to utilise corrupt officials in the government to divert government funds or force them to do so under threat... at places resources allocated for development have not reached the beneficiaries... but have instead been used to finance ULFAs gun running... hence infrastructure development in Assam continues to be hampered with poorer communication links.39 If the drugs-arms trafficking linkage gets crystallised and consolidated the situation would be very alarming. The situation looks very grim already even if we go by the number of terrorists killed in 1998 as seen below.

256

Lama

The June 1999 bomb blast in New Jalpaiguri railway station in north Bengal, killing many Kargil bound soldiers, has serious implications. The subsequent claim by the ULFA that it did this bombing with the help of the ISI should in fact be an eye opener to security personnel, policy makers and civil society at large in the region particularly when it took place in an area which is the meeting point for four countries: India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal.

Table 7 Terrorists Killed in India (1998) Jammu-Kashmir Assam Manipur Nagaland Tripura Total Source: 930 161 91 59 26 1,269

The existence of such a nexus is further confirmed by the news reported in the Hindustan Times that the districts of north Bihar specially those on the Indo-Nepal border are flooded with regular arms obtained under dubious licenses procured from Nagaland. The Motihari police has seized 41 such weapons that include double barrel and single barrel guns of .12 bore rifles of .315 calibre. A glance at the couple of licenses claimed to have been procured from Nagaland revealed that they were issued neither by the deputy commissioner nor additional deputy commissioner.40 This article has shown that the problems of troubled north-eastern states of India will remain very difficult in the years to come. The central governments response to the political problems of the region has been one of creating more states, all of them rather small in area, a point illustrated in Table 1 earlier in this article, and one that could be seen even more effectively by a glance at a good atlas. But the creation of more states has not met the political problems adequately. As Table 6 would show, the number of insurgent groups operating in these states has also kept increasing. This on its own is serious enough without the drugs and arms smuggling analysed in this chapter, a dangerous situation for which the central government has been unable to provide any effective long term measures.

Data provided by the Union Home Minister L K Advani in the Lok Sabha, 22 December 1998, quoted by Hindustan Times, 23 December 1999.

Mahendra P Lama is Associate Professor, South Asian Division, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Notes 1 Cannabis: All plants of the genus cannabis produce within them a complex chemical called Delta 9 Tetrahydrocannabinol known as THC. Three varieties of the plant produce THC in significant amounts, Cannabis Sativa, Cannabis Indica and Cannabis Ruderalis. Of these Sativa produces THC in the highest concentration and is therefore the preferred source of the drug. These cannabises are used in the form of herbal, resin and oil. The effects are bodily warmth, relaxation, happiness and congeniality and pleasure from the company of the people around them, and adverse effects include dryness of the mouth, nausea and dizziness to cancer and heart disease. Heroin is produced by chemical processing of raw opium (obtained from certain varieties of poppy, particularly, oriental opium poppy, Papaver Somniferum), a chemically bonded synthesis of acetic anhydride, a common industrial acid, and morphine, a natural organic painkiller extracted from opium poppy. Morphine is the key ingredient. The acidic bond simply fortifies the morphine, making

India's North-East States: Drugs, Small Arms 257

it at least ten times more powerful than ordinary medical morphine and strengthening its addictive characteristics. David Emmett and Graeme Nice, Understanding Drugs: A Handbook for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1996 and Phanjoubam Tarapot, Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking in North Eastern India, Delhi, Vikas, p 56. 2 3 Indicators: non-plan expenditures have gone up many fold. The share of the central government in the revenue has gone up to over 80% in many of the states. Jayanta Madhab, North-East: Crisis of Identity, Security and Underdevelopment, Economic and Political Weekly, Bombay, 6 February 1999. M N Karna, Assessment of Drug Abuse, Drug Users and Drug Prevention Services in Guwahati, Shillong, Department of Sociology, North Eastern Hill University, and Ministry of Welfare, Delhi, Government of India, 1989. Statement given by the Chief Minister of Assam, Prafulla Mahanta, Telegraph, Calcutta, 22 September 1997. Deccan Herald, Bangalore, 17 September 1997. Outlook, Delhi, 1 February 1999. Hindustan Times, Delhi, 25 October 1998. Outlook, Delhi, 1 February 1999. Daniel Avila Camacho, Interrelationship Between Drug Trafficking and the Illicit Arms Trade in Central America and Northern South America in Pericles Gasparini Alves and Daiana Belinda Cipollone (eds), Curbing Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms and Sensitive Technologies: An Action-Oriented Agenda, New York, United Nations, UNIDIR/8/16 1998. The Geopolitical Drug Dispatch, Edition No.14, December 1992, p 3 as quoted in All Quiet on the Western Front? The situation in Chin state and Sagaing division, Burma, Images Asia, Karen Human Rights Group and The Society Institutes Burma Project, January 1988, pp 58-64. Mary H Cooper, The Business of Drugs, Washington DC, Congressional Quarterly Inc., 1990. United States General Accounting Office/National Security and Internal Affairs Division, Drug Control: US Heroin Program Encounters Many Obstacles in Southeast Asia, GAO/NSIA-96-83, March 1996, p 3. All Quiet on the Western Front?, op.cit., pp 58-64. Francois Casanier, A Narco-Dictatorship in Progress, Burma Debate, March/April 1996. The Geopolitical Drug Dispatch, op.cit., p 1. Karna, op.cit. Tarapot, op.cit., p 99. Jasjit Singh, Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms: Some Issues and Aspects in Alves and Cipollone (eds), Curbing Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms..., op.cit. J F Holden-Rhodes, Sharing the Secrets: Open Source Intelligence and the War on Drugs, West Port, Connecticut, London, Praeger, 1997. Ministry of Home Affairs, Annual Report 1995-96, Delhi, Government of India, 1996.

5 6 7 8 9 10

11

12 13

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

258

Lama

22 23

Times of India, Delhi, 5 September 1997. Tara Kartha, Non-conventional Threats to Security: Threats from the Proliferation of Light Weapons and Narcotics, Strategic Analyses, Delhi, IDSA, May 1997. Tarapot, op.cit., p 111. Antonio Garcia Revilla, Inter-relationship Between Small Arms Trafficking, Drug Trafficking and Terrorism in Alves and Cipollone (eds), Curbing Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms..., op.cit. Outlook, Delhi, 1 February 1999. Ibid., p 41. Hindustan Times, Delhi, 25 October 1998. Kuensel, Thimphu, 8 August 1998. S H M Rizvi and Shibani Roy, Psychotropic Drug Addiction and AIDSA Counter-Productive Phenomenon in Manipur, Social Sciences, Special Issue, Shillong, North Eastern Institute of Anthropological Research, June-December, 1993. Sundar Daniel, A Case of Redefinition, paper presented at the Seminar on the Malaise of Drugs and Drug Trafficking in North east India organised by State Resource Centre, Shillong, North Eastern Hill University and ICSSR, 1997. It costs only 140 to buy the raw materials to make 1kg of cocaine in a Colombian laboratory, but the total price collected for it, split into many thousands of doses on the streets, is about 70,000, virtually all of which goes into astronomical profits for a wholly criminal hierarchy from the barons to the street pushers. If drugs were legalised the price would be controlled by market forces (with added taxation) and so could fall dramatically, but the producers and distributors, deprived of their huge profits, would vastly increase their production. There would be a limit to taxation, above which it would defeat its object by promoting a thriving black market. There would therefore be a massive increase in addiction. Richard Clutterbuck, Terrorism, Drugs and Crime in Europe after 1992, London, Routledge, 1990.

24 25 26 27 28 29 30

31

32

33 34

World Drug Report, United Nations International Drug Control Programme, New York, Oxford University Press, 1997. John Mao and Mary C Smite, AIDSThe Pandemic Menace with special reference to Manipur, Social Sciences, Special Issue, Shillong, North Eastern Institute of Anthropological Research, JuneDecember 1993. Hindustan Times, Delhi, 1 June 1999. U C Bhattachajee, AIDS Menace in North-East India: Some Measures of Control, Social Sciences, Special Issue, Shillong, North Eastern Institute of Anthropological Research, June-December 1993. Bertil Lintner, Burma in Revolt, p 325, as quoted in All Quiet on the Western Front? op.cit., p 63. James A Inciardi, The War on Drugs: Heroin, Cocaine, Crime, and Public Policy, California, Mayfield Publishing Company, 1984, pp 183-185. Bleeding Assam, Ministry of Home Affairs, Delhi, Government of India, 1998 as quoted by Hindustan Times, Delhi, 24 October 1998. Hindustan Times, 1 February 1999.

35 36 37 38 39

40

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Terror and ParadoxDocument2 pagesTerror and ParadoxSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- What Has Turkey Learned From TerrorismDocument5 pagesWhat Has Turkey Learned From TerrorismSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hawala SystemDocument11 pagesThe Hawala SystemnewtomiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dynamics of Extremism in Jammu and KashmirDocument9 pagesDynamics of Extremism in Jammu and KashmirSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Securing Tyrants or Fostering Reform US Internal SDocument15 pagesSecuring Tyrants or Fostering Reform US Internal SSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- EUCounter-TerrorismStrategy pdf11Document25 pagesEUCounter-TerrorismStrategy pdf11Sunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Budgam: Breaking The Myth of Excessive Force by Security Forces in KashmirDocument14 pagesBudgam: Breaking The Myth of Excessive Force by Security Forces in KashmirSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Intifada PDFDocument31 pagesIntifada PDFSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dpko IndiaDocument129 pagesDpko IndiaSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

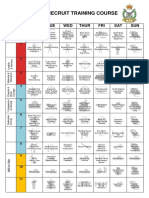

- Army Recruit Course Day by Day V8 PDFDocument1 pageArmy Recruit Course Day by Day V8 PDFSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- India, Pakistan, and The Kashmirk SolutionDocument40 pagesIndia, Pakistan, and The Kashmirk SolutionSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosing Foreign Policy of Nepal: Krishna H. PushkarDocument9 pagesDiagnosing Foreign Policy of Nepal: Krishna H. PushkarSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Entangled Triangle of Nepal India and ChinaDocument6 pagesThe Entangled Triangle of Nepal India and ChinaSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Officer Candidate Assesment PDFDocument15 pagesOfficer Candidate Assesment PDFSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- It Mba ProspectusDocument44 pagesIt Mba ProspectusKaran PopliPas encore d'évaluation

- Jammuandkashmir Apresentation 120405050624 Phpapp02Document44 pagesJammuandkashmir Apresentation 120405050624 Phpapp02Sunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Opportunities and Threats in Terms of Economic Growth and DevelopmentDocument17 pagesOpportunities and Threats in Terms of Economic Growth and DevelopmentSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Close Quarters Battle: Compiled by A. AMORETTIDocument8 pagesBasic Close Quarters Battle: Compiled by A. AMORETTIKristjan PurrePas encore d'évaluation

- Spoken KashmiriDocument120 pagesSpoken KashmiriGourav AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- Gps in ManipurDocument10 pagesGps in ManipurSunny ChohanPas encore d'évaluation

- WWII 1942 British CommandosDocument142 pagesWWII 1942 British CommandosMarcos Nabia100% (5)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Drug EduDrug Education and Vice Controlcation and Vice ControlDocument9 pagesDrug EduDrug Education and Vice Controlcation and Vice ControlChristian Dave Tad-awanPas encore d'évaluation

- Border Control and SecurityDocument6 pagesBorder Control and Securityfreshe RelatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Aff, RedactedDocument5 pagesAff, RedactedJon WilcoxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Drug War in MexicoDocument6 pagesThe Drug War in Mexicoapi-142789006Pas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Enforcement 1999 PDFDocument198 pagesDrug Enforcement 1999 PDFHowardPas encore d'évaluation

- Gabriel Vargas Laredo CartelDocument15 pagesGabriel Vargas Laredo Cartelildefonso ortizPas encore d'évaluation

- Edgar Valdez Villarreal, La Barbie. Perfil de La DEADocument2 pagesEdgar Valdez Villarreal, La Barbie. Perfil de La DEAVictor Hugo MichelPas encore d'évaluation

- Jao Pho and Red WaDocument4 pagesJao Pho and Red WaJericho ParasPas encore d'évaluation

- GAC 008 Assessment Event 4: Academic Research EssayDocument7 pagesGAC 008 Assessment Event 4: Academic Research EssayKlarissa AngelPas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge IGCSE™ Global Perspectives 0457Document7 pagesCambridge IGCSE™ Global Perspectives 0457Revathi NarayananPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti AcidsDocument8 pagesAnti AcidsMohammad Ali Abu Ma'ashPas encore d'évaluation

- Cali CartelDocument7 pagesCali CartelMigIwaczPas encore d'évaluation

- El Chapo.s-1 Filed IndictmentDocument49 pagesEl Chapo.s-1 Filed IndictmentSimone Electra WilsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug DealerDocument6 pagesDrug DealerDeclan Max BrohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Drug Policy and Security Term Paper 1Document21 pagesDrug Policy and Security Term Paper 1nah ko ra tanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hua MangaDocument138 pagesHua MangagdeskPas encore d'évaluation

- How Charas Changed Life in MalanaDocument11 pagesHow Charas Changed Life in MalanasimsalabimbambasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fredy Cesar Olaya Reyes - CB - CagenDocument2 pagesFredy Cesar Olaya Reyes - CB - CagenOlga Constanza Cruz NovalPas encore d'évaluation

- Abu Farhan Azmi - The Biggest Substance AbuserDocument1 pageAbu Farhan Azmi - The Biggest Substance AbuserSania AnsariPas encore d'évaluation

- Genre Analysis Final DraftDocument6 pagesGenre Analysis Final Draftapi-284031188Pas encore d'évaluation

- Philadelphia/Camden: High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area Drug Market AnalysisDocument16 pagesPhiladelphia/Camden: High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area Drug Market AnalysislosangelesPas encore d'évaluation

- Shared Responsability US-Mexico Policy Options For Confronting Organized CrimeDocument388 pagesShared Responsability US-Mexico Policy Options For Confronting Organized CrimeMario Chaparro100% (2)

- OrganicDocument35 pagesOrganicKristina CoePas encore d'évaluation

- The Right and Duties of Other States in The EEZDocument6 pagesThe Right and Duties of Other States in The EEZOmank Tiny SanjivaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Jewish MobstersDocument11 pagesJewish Mobstersmamacita puerco100% (1)

- 02 Drug Trafficking Zhang PaperDocument22 pages02 Drug Trafficking Zhang Paperdogar153Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Kurdish Workers Party PKK As Criminal Syndicate Funding Terrorism Through Organized Crime A Case StudyDocument21 pagesThe Kurdish Workers Party PKK As Criminal Syndicate Funding Terrorism Through Organized Crime A Case StudyRıdvan BeyPas encore d'évaluation

- 01576-Colombia Coca Survey 2005 EngDocument118 pages01576-Colombia Coca Survey 2005 Englosangeles100% (1)

- Jack Ben English PowerpointDocument23 pagesJack Ben English Powerpointapi-239231458Pas encore d'évaluation

- DSD Math Ga Part 7Document49 pagesDSD Math Ga Part 7Commerce ClassesPas encore d'évaluation