Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Egoist 42

Transféré par

Reina GonzalesDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Egoist 42

Transféré par

Reina GonzalesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

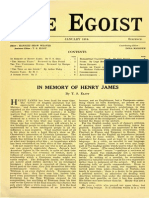

Published Monthly

THE

No. 2 . V O L . I V .

Editor: H A R R I E T S H A W W E A V E R .

Assistant Editors : RICHARD ALDINGTON.

EGOIST

F E B R U A R Y 1917.

SIXPENCE.

Contributing Editor : D O R A M A R S D E N , B.A.

H. D.

CONTENTS

PAGE PAGE

OBSERVATIONS PYGMALION.

PRELIMINARY By H . D .

TO

A .

DEFINITION . . .

OF 17 21

THE

FUTURE

OF A M E R I C A N HUMOUR.

B y Yone Noguchi

25 26

" IMAGINARY."

B y D . Marsden

ENVY. PASSING

B y F. S. Flint PARIS. By M. C. . . . . .

JAMES JOYCE. Kristian)

AUTUMN THE RAIN.

B y E z r a P o u n d (with W o o d c u t by R o a l d . . . . . .

B y D . H . Lawrence Sinclair . . . . . .

. 2 6

.21

22

EZRA POUND. Bosschre

SERIAL

Translated from the F r e n c h of J e a n . . . . . . . .

.

de .

.

27

29

T H E EXILES.

CHILD.

B y M a d a m e Ciolkowska .

B y May

.

.

.

.

23

.24

STORY TARR.

B y Wyndham Lewis

C O R R E S P O N D E N C E : Dreiser Protest

.30

VI.

O B S E R V A T I O N S PRELIMINARY T O A DEFINITION O F " I M A G I N A R Y "

BY D. MARSDEN

I THE difficulties standing i n the way of a satisfactory definition of imaginary very greatly exceed those presented by the term real, which was the subject of our last study. The reason is that the activities with which the latter is concerned, i.e. whether a name has been rightly or wrongly applied to a given phenomenon, can be expressed i n terms which are comparatively superficial. The term imaginary, on the contrary, embodies a distinction between v i t a l activities so basic that an adequate consideration of them forces a definition of the term life itself. That is, the ontological questions which, with anything approximating to skill one might successfully evade in considering real, become the ever-present substance of one's care i n considering imaginary. It is perhaps desirable therefore to state our motive for insinuating a study of imaginary between real on the one hand, and its opposite, illusory, on the other. Our justification is, that i n order to close up certain leakages of meaning i n the term real itself i t is necessary to do so. There exists a loosely held but widespread assumption, which psychologists themselves show no anxiety to undermine and to which indeed the perfunctory manner i n which psychology deals with imagination is directly due, that the imaginary stands in some sort of antithetical relation to the real. Y e t that such assumption is erroneous is easily demonstrable. There is nothing i n the meaning of either term to render the one exclusive of the other. On the contrary, both can be, and are, simultaneously applied to one and the same image : as when we quite correctly say of an image, " It is really imaginary.'" The two terms do bear a close relation to each other, but i t is not one of antithesis. The actual antithesis of real is, as we have already indicated, the term illusory. (2) The first preliminary to our study then w i l l be

to indicate precisely what the relationship between imaginary and real is. It w i l l be found that the ground has already been partly covered i n our chapter on the real. It w i l l moreover be further covered i n connexion with illusory. A t this point therefore we shall merely have to state the relationship i n its categoric form. Thought is a special mode of application of the powers of imagination. W h e n we think, we use imaginary images i n a particular way. The element which distinguishes thought-inspired a c t i v i t y as against instinctive activity is the imaginative one ; and men's minds have rightly apprehended the facts of the situation when they, speaking of the power of thought i n general, usually intend that one shall understand thereby imagination rather than thought as the more characteristic and inclusive term. (3) The characteristics which distinguish thought and imagination from each other can be reduced i n words to very modest dimensions, though their issue in action involves a l l the difference which lies between the imaginary and the real. F o r thought produces the last and imagination the first. W e w i l l state the difference thus : I n imagination the imaginary image combines with like imaginary images. I n thought imaginary images pair, one by one, each w i t h its corresponding external image. T h i n k i n g is therefore the interlacing of the imaginary with its external counterpart (as presumed). If when the latter is subjected to certain standard usages such presumption proves itself justified, upon the external image is superimposed a distinctive label. A s product half of the imaginary and half the external i t now constituted a realized image. I n such manner does the imaginary image intertwining with the external call into existence the world of reality. After a like manner also does i t create that of illusion. (4) W h e n we compare external w i t h imaginary images, we find many common points of likeness. B o t h alike are, felt. B o t h show liveliness and strength and both are equally capable of showing aspects of

18

THE

EGOIST

February 1917

keen pleasure and acute pain. Judged from the point of v i e w of seeking an increase of satisfaction alongside a d i m i n u t i o n of pain, however, an outstanding difference presents itself between them, i n that imaginary images show an orderliness and intelligence of sequence i n pursuit of these ends which is constantly g i v i n g a lead to the external world. It is the supe r i o r i t y of the imaginary i n this very respect that gives purpose to the processes of thinking. Thought is a bridge which the human species has constructed as a means whereby the external order of images can be impregnated w i t h something of the imaginary's particular quality i n this respect. The real world as the immediate issue of thought is man's ingenious a n d unique creation giving body and form to this precise intention, giving a lead to the external world. II (5) H a v i n g dealt w i t h the imputed antithesis of imaginary, our second preliminary will be concerned w i t h its actual antithesis. The conception which opposes and completes that of the imaginary image is an external one. S o ! A t the very threshold of our i n q u i r y we are confronted with the riddle alike of philosophy and sciencethat of space. Whatever explanation one may be prepared to give of this element of disruption and cleavage operating among the t o t a l i t y of life's images, space must always remain the factor from which the imaginary derives its significance. No account of imaginary therefore can proceed any part of its course without giving some account of space also. W e shall not pretend to offer here any detailed account of space. W e shall merely hope to be able to indicate on what lines any such account must travel, the facts of life being what they are. (6) L e t the vital unit be described as the unit of feeling, the unit of cognition, life, the ego or the universe. B y whatever name i t is called, its essential characteristics w i l l i n each case be identical : it will comprehend within its borders distinction, difference, a n d division. Essentially, life is the unit which cannot be described (because it cannot be experienced) under a single aspect. Taken throughout its entire range from the cell which is simply a stomach to the complexest type of humanity, the number of elements under which the fact of life is expressible is threefold. W e can speak of life even as we can experience it, only as a trinity: the t r i n i t y of organism, external world, and space. W e might say that these three represent i n an unrupturable union life's two poles, together with the axis which at once joins and divides t h e m ! A n d just as one pole is meaningless save i n relation to the other and both meaningless save i n relation to a dividing and uniting axis, so is an organism meaningless apart from its world, and both together meaningless apart from space. Hence, whether we elect to say that life is the establishment of an organism, or the establishment of space, or the b i r t h of the external world matters nothing. E a c h statement equally inplicates the remaining two. E a c h portends the same single but triune-faced fact of life, of a universe, and of an ego. L e t us once more traverse the selfsame fact. L e t us begin b y saying that the minimum of life is the establishment of a Self. E v e n so, the same logical chain promptly ravels down. F o r the meaning of self exists only i n relation to another termthe not-self, while the relation of a self to a not-self can be postulated only b y postulating also the existence of some principle of division. A n d that brings us back to space a g a i n ! A l w a y s the same three i n one and one i n t h r e e ! (7) Before considering whether even this triune aspect of life exhausts the prime and initial postulates necessary for the bare statement of life, let us see whether it is possible to assemble a set of conditions

which could illustrate the facts as far as stated. Can we establish a unified s y s t e m ; a self-contained universe comprising within itself two worlds i n t i mately combined and yet drastically alienated; alike yet opposite ; different yet interacting i n mutually fitting adjustment one with the other? L e t us t r y to construct after the dynamic model a logical replica of such conditions. L e t us postulate a nodule of energy comprising force i n a state of steadily increasing tension. The tension growing, let us say that finally it reaches explosion-point; and the explosion effecting itself it has to show as its sequel a disintegration of the initial force into two streams differing from one another as positive to negative, equal but opposite and inclining to opposite poles. Say that each thread of each stream has its own t w i n poles, a n d that the positive poles of a l l the threads come together and meet round about a point, thus rendering the latter a nucleus from which the threads joining them w i t h the negative poles strike outwards like r a d i i from the centre to the circumference of a sphere. A d d also that knots form i n the outgoing threads, thus pro ducing denser patches in the finer whole, and we can begin to allocate the rles. (8) The cluster of intercommunicating positive poles represents the organismthe self. The fine threads extending divergently from the centre to a l l points of the universe are the substance of space along which travel the currents passing between their respective poles and to whose contact w i t h the positive poles we give the name sensation. A t a relatively small distance from the actual centre, i.e. from the nuclei of the nervous system, there is woven out of the relatively dense and close-packed threads an outer line of defencea system of limited entrances and exitsby way of which as the sense-organs the currents pass inward from the negative poles. The expanse of space is the direct measure of the strength of propulsion existing i n the total v i t a l system. The knots i n the spatial substance are the furnishings of space : the objects comprising the external world. Life itself is the establishment and maintenance of space and the passage of the positive and negative currents travelling through space between their respective poles. Conversely must death be the shrinkage to vanishing-point of the threads of space. When " t o dying eyes the casement slowly grows a glimmering square," the last weak rays of space are swiftly shrinking, fading, fainting. Then suddenly they are n o t ; and life's brief adventure is finished : Organism, W o r l d , Space, and Time alike involved i n the one common dissolution. (9) W h i c h brings us to the rle, i n the logical scheme of things, which has been labelled Time. F o r , once the fact of life has been rendered capable of logical manipulation (if we may use such a conjunction of term) by the postulating of a self, a world, and space, it becomes evident that this threefold rendering by no means exhausts the whole of life's prime aspects. It becomes clear that life is not merely a triune but a multi-featured f a c t ; so that when one of its forms (to w i t : man) is taken with a desire to paraphrase it by means of verbal symbols, these same symbols will run to a lengthy list before they have taken account of even its most essential features. Accordingly, the rle of Time equally w i t h those of space and the world is inherent i n the account already given wherein we paraphrased the life's beginnings. If, for instance, the pre-vital condition be one of tension between forces, the one of which has to secure a preponderance of strength before the v i t a l condition can establish itself, the system when so established will still retain within itself, in, addition to forces of a v i t a l tendency, those forces which were a n t i - v i t a l . Life indeed w i l l represent merely the domination of these latter forces b y the former. That is, while the. latter are dominated so long as life maintains itself, they are not annihilated. Accordingly, throughout

February 1917

THE

EGOIST

19

the period of existence of every v i t a l system, certain forces w i l l remain within it inimical to its preserva t i o n and maintenance. Not a l l currents therefore which travel between pole and pole can be equally v i t a l l y welcome; consequently the characteristic which we call preference w i l l hold a prime place i n every system. It is this fact of preference which constitutes the all-important v i t a l attitude of affir mation and negation: the sense of Is and Is-not which attends i n the nicest discrimination upon a l l things. The same fact, too, yields the attitude of desire and repulsion: satisfaction and frustration; a l l of them primary basic v i t a l attitudes. A s for t i m e : vital time must be the sustentation of effort: the actual yielding of the toll levied upon a system's strength to the end that the forces within it making for its maintenance shall prevail against those which are warring against it. Thus time is the small change into which the v i t a l strength of the system converts itself, and the form i n which from its advent to its close i t spends and exhausts itself upon its preferences. (10) The most obvious objection to any such paraphrase of the facts of life as the one just given is that it makes space and time into mere items or adjuncts of the individual v i t a l system : beginning with i t and ending with it. This objection, given force to as i t is on the one hand by consideration of the illimitable and abiding-seeming character of the spatial " u n i v e r s e , " and on the other b y the unending tale of the world's history, i n time looks sufficiently overwhelming. To our understanding, however, it seems that i n a complete statement of a theory on these lines these objections, while serious, can be shown to stop just short of total overwhelmingness. A n d at this point we must leave the subject for the time being. III (11) The first important corollary to such a concep tion of space is that i t forces an immediate overhauling of the dualism with which Descartes handicapped modern philosophy at its inception, and which has preyed upon its strength from that day to this. The essential oneness in difference of the cognitional activity involving as it does both " p o l e s " (positive and negative, subjective or objective, just as we choose to name them), lays a ban upon a division into a " m i n d - s t u f f " which cognizes on the one hand and a " s t u f f " of a different k i n d which is cognized on the other. Descartes' first postulate of a res cogitans versus a res extensa is left without any logical base, and presents itself as a distortion of a l l that is characteristic of life as the unit of cognition and feeling. The attempt to set the " c o n t e n t " of cognition over against a cognitive " a c t i v i t y " abstracted by some asserted means from cognition as a whole, can hope for as much success as an analo gous attempt to outline the course of an express train by constructing a stone wall across the railway-track. Such division, however, has obtained what practically we may call universal acceptance. The fact that it has accounts for the paralysed condition i n which philosophy finds itself and for the open andshall we sayshameless confession of impotence which philosophy's most earnest and strenuous servants find themselves driven to make. W e have already quoted Spencer's opinion that this dualismwhose genuineness he accepts as wholeheartedly as any transcendentalistis one " n e v e r to be transcended while consciousness lasts." A writer of like mental complexion, D r . Tyndall, s a y s : " T h e passage from the physics of the brain to the corresponding facts of consciousness is unthinkable. Granted that a definite thought and a definite molecular action i n the brain occur simultaneously, we do not possess the intellectual organ which would enable us to pass by a process of reasoning from the one to the other. They appear together, but we do not know w h y . "

A n d H u x l e y says, " I know nothing whatever, and never hope to know anything, of the steps by which the passage from molecular movement to states of consciousness is effected." (12) A m o n g their very many differences and dis agreements i n creed and temperament, the one count on which idealist and (latter-day) materialist opinion are at one is that the phenomena of thought and matter present nowhere a mutual point of contact. B o t h schools hold that the two sets of phenomena run parallel courses and, because parallel, they remain for ever apart. A difference i n manners perhaps : a deeper estimation of the value of suavity may inspire idealist opinion to garb itself i n a more soothing raiment, and it might say that though the antithesis of thought and matter is a positive and indeed supreme fact, nature would not be so u n k i n d as to leave us without a reconciling principle somewhere ; that i n fact there is a reconciling principle but that its place of residence is unfortunately outside the boundaries of Time and Space. W h i c h is not much use to people whose interests a l l lie within Time and Space ! (13) Obviously this dualism which modern philo sophy has maintained from first to last is a matter i n which the imaginary has a paramount concern. Since we have claimed that imagination is the element of all that is essential i n thought, we must be prepared to make the imaginary responsible for a l l that has rendered thought as contrasted with matter a mystery. F o r us this dualism which we hold is not impossible of resolution will have to be described as that of imagination versus matter, rather than that of thought (or mind) versus matter. (14) While the working-out of the details of our position must be postponed u n t i l we have dealt with imaginary itself, we can here state a number of conclusions which will show what direction our argument is taking. I n the first place, i n accordance with the theory of space just outlined, we maintain that cognized images cannot be opposed to some cognizing activity which " a c h i e v e s " them. There is nothing i n experience to correspond w i t h a res cogitans and a res extensa. Cognition, feeling, life, reduced to its very simplest element, constitutes a unity comprehending both aspects. Abstract from it either, and there remainsnothing! The spatial pole (if we may so describe it) is not one whit less involved i n any single cognition than the organic pole, and vice versa. The current of movement which effects its course between the two achieves one single, unbroken, compound, cognitive fact. That com pound creation we know under the description of things : of objects occupying space. Matter, that is thinghood, is the activity of both self and not-self acting as a whole. (15) It is to be noted how persistently philosophy directs a b l i n d eye upon this elementary fact of cognition. That every spatial fact is just as much a state of consciousness as is any inner or mental fact is always ignored i n practice i n spite of the lipservice which is paid to it i n theory. Philosophers speak of " t h e passage from molecular movement to states of consciousness," as though i t were possible to conceive of them as something other than states of consciousness. Y e t molecular movement has as much claim to be regarded as just such a conscious state as a state of bliss or of agony or any k i n d of feeling whatsoever. I n this respect there is no distinction to be drawn between the most ultimate ray of the remotest star or the instrument which fixes it, and the glow of exultation following upon the ray's discovery. A l l are states of consciousness equally. So too are the little shapes called figures under which the changes observed i n a muscle are subsumed as quantities, together with the muscle itself, w i t h the scalpel and the forceps and a l l the multitudinous images which constitute the physical.

20

THE

EGOIST

February

1917

h i s t o r y of matter. I n short, i t is not possible to pass from a n y t h i n g whatsoever to a state of conscious ness, simply because everything whatsoever is a state of consciousness. (16) Where then are we to look for the source of confusion? T h a t such a source exists is plain. The antithesis of m i n d versus matter would not have been so readily accepted unless i t possessed some t h i n g more than a mere show of speciousness. This is our t h e o r y : the mistaken distinctions as between a res cogitans and a res extensa has been inspired by the distinction genuinely obtaining between two orders of cognition, i.e. that between cognition and recognition. That we are i n possession of the right clue i n holding that the dualistic distinction has to do w i t h a new form of cognitional activity which contrasts w i t h the more elementary form of cognition is supported at the outset by the fact that philosophy accepts without demur a l l the facts of cognition. Otherwise how account for the easy, not to say glib way i n which philosophers refer to the facts of physics: all of them cognitive facts. It is an activity which is like and yet unlike cognition which introduces uneasiness. It is the activity which supplements cognition which presents the stumbling-block. That a c t i v i t y is recognition: the activity which has become possible because man has discovered the way to create imaginary images. I n the slow evolution of life's forms the imaginary image has supervened upon the cognitional world, and life has found itself impreg nated w i t h a new power. It is this newly acquired power which as thought and mind has baffled men's understanding from the beginning of his history. This revolutionary development i n which cognitional a c t i v i t y is supplemented by an activity higher and more complex than itself but not basically different from it, made its appearance i n creation with the advent of man. The instrument by which it effected itself, and b y which it still develops from strength to strength, is that of S P E E C H . B y means of speech m a n has effected among his k i n d i n a k i n d of loopline extension at cognition's positive polea prolonga t i o n of the current which in instinctive activity eventuates i n an immediate and forthright response whenever the latter is stimulated by a current running i n w a r d from the spatial pole. It is in the mechanism of this " p a u s e " : rather i n this extension of the current's circuit, that the substance of our theory of the imaginary is to be sought. IV (17) The foregoing section summarized amounts to t h i s : O n grounds which we propose soon to develop, we conclude that the supposed antithesis of matter and m i n d is actually reducible to what amounts to no more than a mere distinction between two forms of cognition : cognition proper and recognition. These two activities can be represented by their distinctive products as those productive characteristically of the world of external objects and the world of imagina tion. B o t h these worlds meet and combine to make the world of t h o u g h t ; while going back to the origin of the entire distinction again we have to say that the development of recognition out of its elemental form cognition was made possible i n man because with h i m began the era of Speech. I n short, life's dualism is a mistake which can be explained while it cannot be defended. (18) This side of the subject we now leave to deal w i t h another subject quite different from dualism intrinsically, but one which in its application has become closely implicated i n dualism's defence. W e refer to the presentment of the theory of psycho physical parallelism which has latterly secured a dominant position as that which explains most acceptably the theory of dualism. I n our opinion the enormities of the explanation exceed even those of the theory which it seeks to explain, inasmuch as

it misconstrues the entire function of science a n d the whole meaning of knowledge. The theory m a i n tains that while no state of consciousness ever takes place without concomitant changes i n the neural system, yet is there no causal connexion between the two. The neural changes r u n their course con comitant with, and correlated to the changes i n consciousness, but neither course ever overflows the limits of its own self-contained system so as to establish direct connexion with the other. The passage from Professor James which we quote below will describe the position : though i t should be noted that of parallelists there are two varieties: one might say a higher and a lower accordingly as each holds that the one or the other of the self-contained systems is the dominant one. " I f we knew thoroughly the nervous system of Shakespeare, and as thoroughly a l l his environing conditions . . . we should be able . . . to show w h y his hand came to trace on certain sheets of paper those crabbed little black marks which we for shortness' sake call the manuscript of Hamlet. W e should understand the rationale of every erasure and altera tion therein, and we should understand a l l this without i n the slightest degree acknowledging the existence of the thoughts i n Shakespeare's m i n d . . . . On the other hand, nothing in a l l this could prevent us from giving an equally complete account of . . . Shakespeare's spiritual history, an account i n which every gleam of thought and emotion should find its place. The mind-history would run alongside of the body-history of each man, and each point i n the one would correspond to, but not react upon, a point in the other. So the melody floats from the harpstrings, but neither checks nor quickens its v i b r a t i o n s ; so the shadow runs alongside the pedestrian, but in no way influences his steps." (19) N o w what k i n d of reason is offered i n defence of the bold assertion that phenomena, presenting themselves in such unvarying interconnexion as the theory of parallelism says neural and conscious pro cesses do, stand i n no sort of causal connexion the one with the other? W e will let its advocates speak for themselves. Professor Stout (who would be classified as of the " h i g h e r persuasion) puts the reason expressly i n the passage i n the subjoined quotation which we have marked by italics : " W h e n we come to the direct connexion between a nervous process and a correlated conscious process, we find a complete solution of continuity. The two processes have no common factor. Their connexion lies entirely outside of our total knowledge of physical nature on the one hand, and of conscious process on the other. The laws which govern the change of position of bodies and of their component atoms and molecules i n space, evidently have nothing to do with the relation between a material occurrence and a conscious occurrence. "No reason in the world can be assigned why the change produced in the grey pulpy substance of the cortex by light of a certain wave-length should be accom panied by the sensation red, and why that produced by light of a different wave-length should be accompanied by the sensation green. It is equally unintelligible that a state of volition should be followed by a change in the substance of the cortex and so immediately by the contraction of a muscle." The writer is here unmistakably arguing that notwithstanding the strict correlation and concomi tance existing between the two processes, science must still further supply a satisfying answer to one particular why or be accounted incapable of establish ing causal connexion between them. N o w let us note minutely what k i n d of query this why represents. W h a t the passage demands to know is why light of a certain wave-length should be accompanied b y the (Continued on page 31)

February 1917

THE

EGOIST

E a c h from his marble base has stepped into the light and my work is for naught. VI N o w am I the power that has made this fire as of old I made the gods start from the rocks am I the god or does this fire carve me for its use?

21

PYGMALION

BY

H . D. I

S H A L L I let myself be caught i n m y own light, shall I let myself be broken i n m y own heat, or shall I cleft the rock as of old and break my own fire with its surface? Does this fire thwart me and my work, or m y work does it cloud this l i g h t ; which is the god, which the stone the god takes for his use? II W h i c h am I, the stone or the power that lifts the rock from the earth? A m I the master of this fire, Is this fire m y own strength? A m I the master of this swirl upon swirl of light have I made it as i n old times I made the gods from the rock? H a v e I made this fire from myself, or is this arrogance is this fire a god that seeks me i n the dark? III I made image upon image for m y use, I made image upon image for the grace of Pallas was my flint and m y help was Hephaestos. I made god upon god step from the cold rock, I made the gods less than men for I was a man and they my work. A n d now what is it that has come to pass for fire has shaken m y hand, m y strivings are dust. IV N o w what is i t that has come to pass? Over m y head, fire stands, m y marbles are alert. E a c h of the gods, perfect, cries out from a perfect throat : you are useless, no marble can bind me, no stone suggest. V T h e y have melted into the light a n d I am desolate, they have melted each from his plinth, each one departs. T h e y have gone, w h a t agony can express m y grief?

JAMES JOYCE

AT LAST T H E NOVEL APPEARS* IT is unlikely that I shall say anything new about M r . Joyce's novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I have already stated that i t is a book worth reading and that it is written i n good prose. I n using these terms I do not employ the looseness of the half-crown reviewer. I am very glad that it is now possible for a few hundred people to read M r . Joyce comfortably from a bound book, instead of from a much-handled file of E G O I S T S or from a slippery bundle of type-script. After much difficulty T H E E G O I S T itself turns publisher and produces A Portrait of the Artist as a volume, for the hatred of ordinary English publishers for good prose is, like the hatred of the Quarterly Review for good poetry, deep-rooted, traditional. Since Landor's Imaginary Conversations were ban died from pillar to post, I doubt if any manuscript has met with so much opposition, and no manuscript has been more worth supporting. Landor is still an unpopular author. H e is still a terror to fools. H e is still concealed from the young (not for any alleged indecency, but simply because he did not acquiesce i n certain popular follies). H e , Landor, still plays an inconspicuous rle i n university courses. The amount of light which he would shed on the undergraduate mind would make students inconvenient to the average run of professors. B u t L a n d o r is permanent. Members of the " F l y - F i s h e r s " and " R o y a l A u t o m o b i l e " clubs, and of the " I s t h m i a n , " may not read h i m . They will not read M r . Joyce. E pur si muove. Despite the printers and publishers the B r i t i s h Government has recognized M r . Joyce's literary merit. That is a definite gain for the party of intelligence. A number of qualified judges have acquiesced i n m y statement of two years ago, that M r . Joyce was an excellent and important writer of prose. The last few years have seen the gradual shaping of a party of intelligence, a party not bound by any central doctrine or theory. W e cannot accurately define new writers by applying to them tag-names from old authors, but as there is no adequate means of conveying the general impression of their charac teristics one may at times employ such terminology, carefully stating that the terms are nothing more than approximation. W i t h that qualification, I would say that James Joyce produces the nearest thing to Flaubertian prose that we have now i n English, just as W y n d h a m Lewis has written a novel which is more like, and more fitly compared with, Dostoievsky than is the work of any of his contemporaries. I n like manner M r . T . S . E l i o t comes nearer to filling the place of Jules L a Forgue i n our generation. (Doing the "nearest

* A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, b y J a m e s J o y c e . T H E E G O I S T L T D . R e a d y now, price 6s.

THE

EGOIST

February 1917

t h i n g " need not i m p l y an approach to a standard, from a position inferior.) T w o of these writers have met w i t h a l l sorts of opposition. I f M r . E l i o t probably has not yet encountered very much opposition, i t is only because his work is not yet very widely k n o w n . M y own income was considerably docked because I dared to say that Gaudier-Brzeska was a good sculptor a n d that W y n d h a m Lewis was a great master of design. I t has, however, reached an almost irre ducible m i n i m u m , and I am, perhaps, fairly safe i n reasserting Joyce's ability as a writer. It w i l l cost me no more than a few violent attacks from several sheltered, and therefore courageous, anonymities.

contemporary Europe is caused b y the lack of repre sentative government i n Germany, and by the non existence of decent prose i n the German language. Clear thought and sanity depend on clear prose. They cannot live apart. The former produces the latter. The latter conserves and transmits the former. The mush of the German sentence, the straddling of the verb out to the end, are just as much a part of the befoozlement of K u l t u r and the consequent hell, as was the rhetoric of later R o m e the seed and the symptom of the R o m a n Empire's decadence and extinction. A nation that cannot write clearly cannot be trusted to govern, nor yet to think. Germany has had two decent prose-writers, Frederick the Great and Heinethe one taught b y Voltaire, and the other saturated with F r e n c h a n d with Paris. Only a nation accustomed to muzzy writing could have been led by the nose and bam boozled as the Germans have been by their controllers. The terror of clarity is not confined to any one people. The obstructionist and the provincial are everywhere, and i n them alone is the permanent danger to civilization. Clear, hard prose is the safe guard and should be valued as such. The m i n d accustomed to i t w i l l not be cheated or stampeded by national phrases and public emotionalities. These facts are true, even for the detesters of literature. F o r those who love good writing there is no need of argument. I n the present instance i t is enough to say to those who w i l l believe one that Mr. Joyce's book is now procurable.

EZRA POUND

AUTUMN RAIN

JAMES JOYCE By R O A L D KRISTIAN

THE plane leaves F a l l black and wet On the lawn : The cloud-sheaves I n heaven's fields yet Droop, and are strewn In falling seeds of rain, The seed of heaven Over m y face Falling : I hear again L i k e echoes even That softly pace Heaven's muffled floor, The winds that tread Out all the grain Of tears, the store Of harvest bread F r o m the sheaves of gain Caught up aloft, The sheaves of dead Men and their pain N o w winnowed soft F r o m the floor of heaven, Manna invisible Of a l l their pain F r o m the floor of heaven Finely divisible F a l l i n g as rain.

D. H . LAWRENCE

W h e n y o u tell the Irish that they are slow in recog nizing their own men of genius they reply with street riots and politics. N o w , despite the jobbing of bigots and of their sectarian publishing nouses, and despite the " F l y F i s h e r s " and the types which they represent, and despite the unwillingness of the print-packers (a word derived from pork-packers) and the initial objections of the D u b l i n publishers and the later unwillingness of the English publishers, M r . Joyce's novel appears i n book form, and intelligent readers gathering few by few w i l l read it, and it will remain a permanent part of E n g l i s h literaturewritten by an Irishman in Trieste and first published i n N e w Y o r k City. I doubt if a comparison of M r . Joyce to other English writers or Irish writers would much help to define h i m . One can only say that he is rather unlike them. The Portrait is very different from L' Education Sentimen tale, but it would be easier to compare it with that novel of Flaubert's than with anything else. Flaubert pointed out that if France had studied his work they might have been saved a good deal in 1870. If more people had read The Portrait and certain stories i n M r . Joyce's Dubliners there might have been less recent trouble in Ireland. A clear diagnosis is never without its value. A p a r t from M r . Joyce's realismthe school-life, the life i n the University, the family dinner with the discussion of P a r n e l l depicted in his novel apart from, or of a piece with, all this is the style, the actual w r i t i n g : hard, clear-cut, with no waste of words, no bundling up of useless phrases, no filling in w i t h pages of slosh. I t is very important that there should be clear, unexaggerated, realistic literature. I t is very impor t a n t that there should be good prose. The hell of

February 1917

THE

EGOIST

23

THE EXILES*

IT seems impossible that this war should have spared a breath of life in what lingered here and there of realism i n a r t : that realism to which a l l representation is legitimate but which ever falls short of reality. The significance of tragedy has already undergone a metamorphosis. The tragic situations of our modern romantic and naturalistic schools were drawn from sources some of which have immutable values, others of which are of relative and transient value. These are already on the shelf with a number of sentiments and sentimentalities we can afford to accommodate no longer. The circumstances of war cannot subtract from the pathos of Dombey and Son or Tess or Jude; it does not compete with Balzac. N o t even Zola's divulgences are extinguished. E a c h continues i n its peculiar sphere of drama. B u t the author to come finds himself faced by a world of unprecedented events which he cannot ignore if he persist i n realistic evocations. The trivialities, offered to the public as a derivative from the war, are indicative of a vague, subconscious awakening even among the vulgarest to the impossibility of measuring it with common sense. F o r no common sense can measure the war. F a i l i n g a higher ideal, the purveyors of the public's recreations supply it with diversions making no appeal whatever to the reason. Thus may one briefly explain the detestable futilities indulged i n by all the belligerent countries' capitals and bigger agglomerations during circumstances which call at the very least for flagellation, sackcloth, and ashes if any ever did. Thus may one excuse the antics entirely novel and most wonderfully unseasonable peculiar to the former capital of Puritania. The poets alone have a free field before them. F o r they, having their own code, may, like Kabalists. translate all themes. The prose-writers, the playwrights, will be constrained to make a review of their stock of subjects, problems and plots. The real tragedies, borne i n the souls (and bodies) of the majority, are too bleeding and sore; they are like some of those unhappy wounded who, bandaged a l l over, do not present a patch of immune flesh by which one dare touch them : only the minor tragedies will bear handlingtherefore they won't deserve to be handled. A minor tragedy being no tragedy. E v e r y thing dwindles before the enormous facts defying comment and for which alone allegory has the necessary capaciousness. Probably a great upheaval, some violent transformation such as the one we are experiencing, provoked the Odyssey and Iliad. Most certainly an A r n o l d Bennett or P a u l Bourget w i l l (or ought to) have little to say i n future, though far be it from me to disparage their efforts hitherto, criticism of which should take into account the period for which, and i n which, they wrote. Subsequent to this war there w i l l , or should be, no room for a h y b r i d form of art combining imagination and realism. Between purely creative art and faithful records of facts I can see no occasion for compromise. To the former category alone genius can make answer. In the latter the war w i l l leave a vast bibliography which for sensation and emotions w i l l eclipse a l l the novels and problem-plays any W e d e k i n d or Shaw in the world can write. I t happens that these soliloquies were animated b y a record of the k i n d : Au Sortir des Camps allemands; Soldats interns en Suisse, by Nolle Roger. The writer, apparently a nurse tending the " e x c h a n g e d " F r e n c h prisoners who are recuperating i n the A l p s , relates what she has seen as these things should be t o l d : w i t h as little comment as description w i l l allow

* Au Sortir des Camps allemands ; Soldats interns en Suisse, p a r Nolle R o g e r ( E d i t i o n A t a r , Genve).

and without any fear of overloading her observations. H a v e y o u ever been shown a photograph of a prisoners' camp, for instance, without minutely examining the tiniest detail from the expression on the men's faces to the time b y the clock on the shelf? F o r what can be indifferent where a new world is concerneda new species of men bred by new conditions, new sensations, new privations, new sufferings, new joys even? Mme. Nolle Roger appears to have lived i n close contact with the French and English invalids who have been sent from the German camps to Switzerland from the moment of their crossing the frontier. After such reminiscences as hers, what " f i c t i o n " can make us weep, what psychological conflict deserves examination? A story that will cause y o u to smile twice is a good s t o r y ; a narrative which can on two successive readings draw tears is unsurpassed i n pathos: such a one as this, for example :

The E n g l i s h came last. Chteau d'Oex . . . had been selected for them. " T h e E n g l i s h . . . we saw them at Constance [where the final medical revision is made and prisoners not considered i l l enough for sojourn i n Switzerland are sent back to their camps]. T h e y are i n even worse state t h a n us." The first convoy comprised 304 men, t h i r t y of w h o m were officers. W h e n they crossed the frontier, they too, like the French on the previous d a y a n d the preceding ones, saw, on the extremest point of Swiss soil, facing the G e r m a n sentry, little groups of children w a v i n g flags and t h r o w i n g flowers, a n d a crowd lined all along the railway-line cheering the passing train. A t Z u r i c h the enthusiasm was beyond words. T h e police were overwhelmed. The crowds had to be allowed into the stations. A t Berne refreshments were handed to the " T o m m i e s . " T h e n they continued on their t r i u m p h a n t way. W h e n at six o'clock i n the morning they arrived at M o n t r e u x , the roofs, the terraces were black w i t h a cheering, weeping, laughing multitude. The t r a i n stopped. The notes of the B r i t i s h N a t i o n a l A n t h e m , the same as the Swiss, resounded. A n d the soldiers i n the carriages and the crowd on the quays sang i t together. W e saw these tall, t h i n fellows, w i t h their hollow cheeks a n d drawn features, t r i m i n their k h a k i uniforms or black prisoners' garbs, alight. T h e y h a d put so m a n y flowers i n their caps t h a t they seemed wreathed w i t h roses. Their procession was at once superb and pitiable : a l l those long, damaged bodies, those l i m p and lame, paralysed, twisted, shortened legs w h i c h they seemed to carry before them like something cumbersome, all the crippled N . C . O . ' s ! Others were carried by o n stretchers and so covered w i t h flowers that their uniforms were completely hidden. O n l y the pale, smiling face was visible.

The writer describes the arrival i n the hotels, the assigning of clean, steam-heated rooms and beds with sheets on them, to men who had not known comfort or privacy for months, their emotion at the sight of these luxuries added to the effusions of the receptionsalways spoilt by the haunting vision of the comrades left behind and those, especially, who at Constance saw the gates closed on them. . . . She alludes to the touching idea of the GermanSwiss peasants who received their French and English visitors silently at first, for, not knowing any other tongue, they feared that the sound of their Teutonic dialect would not be agreeable to them. Who said things would fall back into their old places?

MURIEL CIOLKOWSKA

Peasant

Pottery

Row)

Shop

41 Devonshire Street,

Theobald's Road, W.C.

(Close to S o u t h a m p t o n

Interesting British and Continental : Peasant Pottery on sale Brightly coloured plaited felt Rugs

2 4

THE

EGOIST

February 1917

THE CHILD

I. VISIONARY i F R O M the F e r r y i n the east to the F e r r y i n the west, The river and the grey esplanade, A n d the high white palisade Go on and on and on, three abreast. D o w n our lane, To the end of the esplanade and back again, Is as far as y o u can walk when you're four, L i k e me. Doors a l l along i n the palisade, Doors that open and shut without handles or latches or a n y t h i n g else y o u can see; I must count every one, U p to seven ; I mustn't miss o n e ; Because I ' m afraid Of the seventh door. (I don't know w h y : Y o u ' r e like that when you're four.) W h i t e clouds going up from the river, and blue sky and the s u n ; Something w i l d i n the air, Something strange i n the s k y ; I saw G o d there I n the clouds and the sky and the sun. ii I saw h i m with great joy and without any awe (Whatever that i s ) ; A strange, new bliss, U t t e r l y candid, pure from the taint of sin. Y e t I h i d it a w a y ; I h i d it as if it were sin, U n t i l one day I let i t out when I ought to have kept it i n . There must be something odd A b o u t seeing G o d ; F o r they Go worrying, worrying, worrying all the way To make me confess that I saw what They think I saw. A n d i t comes to this, T h a t I set m y small face hard, as who shall say : I ' m sorry. B u t that's what I s a w ; I nod M y head w i t h an obstinate glee; I grin W i t h joy that isn't utterly pure from s i n ; A n d at last I s a y : " D o n ' t y o u wish y o u were me, To be able to see God?" iii They are telling me now they will have to put me to bed, N o t for anything specially wrong I've done, B u t for going on saying the naughty thing I've said. W e l l I don't care If they do put me to bed. If I am more tiresome to-day than ever I've been, If they don't know what I mean, If nobody has ever seen If they have put me to bed, If they have turned out the light, If I am afraid of what conies and stands by your bed at night. I don't care. I know that I saw G o d there In the sky and the clouds and the sun. II.

THEY say

H i g h up, ever so high, A b o v e the clouds and the s u n ; No use at a l l to t r y A n d see God up there. No one has ever seen him with his long white beard and his hair, A n d that funny thing the angels make h i m wear A l l undone. B u t if heaven is God's chair, A n d earth the little stool he kicks away, A n d the sky's a l l stuck between, W h y hasn't somebody seen God's feet coming through? Sharp white feet tearing the blue. A n d there's another thing always puzzles me : They say There are three up there There's Godthat's one ; A n d , Jesus, his little son ; That's t w o ; A n d the H o l y Ghost and the dove coming down from heaven: If you count the dove, that's more Than three, that's four. Why That must be what they mean B y the Three and One. Three and one does make four. (These are the things that bothered me when I was seven.) What do you say about somebody having seen God once, up i n the s k y ? Oh no, it couldn't have been. Wellif I didit was ever so long ago. I was only four, you know. III.

FRIGHT.

FRIGHT

PRISON-HOUSE

I have been naughty to-day. M y mother sits i n her chair, W i t h the dark of the room and the light Of the fire on her face and hair. Her head is turned away, A n d she will not say Good night. I kneel at her knees; I try To touch her face; I throw M y body i n torment down at her feet and cry Quietly there i n my fright. F o r I think, perhaps, perhaps she will die i n the night, A n d never know H o w sorry I am. Surely, surely she will not let me go Out. of her sight, L i k e this, Without a word or a kiss? I was her little lamb Yesterday. I climb the last stair Where the gas burns always low ; In the big dark room my bed Stands very small and white GodGodare Y o u there? I feel with my hands as I g o ; The floor Cries out under my t r e a d ; Somebody shuts the d o o r ; Somebody turns out the light A t the head of the s t a i r ; A n d I know That G o d isn't anywhere, A n d that Mother will die i n the night.

MAY SINCLAIR

G o d hides somewhere

February 1917

THE

EGOIST

25

names of T h a c k e r a y a n d m y beloved D u M a u r i e r a T H E FUTURE OF AMERICAN HUMOUR n d m a n y others) w h e r e o n c e a w e e k t h o s e E n g l i s h professional laughter-makers or, more true to say, t h e s m i l e - m a k e r s , serious a n d s i l e n t i n face p e r h a p s IT w o u l d be a n i n t e r e s t i n g p s y c h o l o g i c a l s t u d y t o trace b a c k h o w the so-called A m e r i c a n h u m o u r more t h a n L a m b ' s Quakers, used to sit for the m a n u f a c t u r e o f h u m o u r o r m e r r i m e n t , I a t once happened to b l o o m i n the g r i m , cold g r o u n d felt as i f I h a d d i s c o v e r e d t h e t r u e r e a s o n w h y of the P u r i t a n m i n d . I n the early days i n A m e r i c a , when people h a d to struggle against the ever-com the E n g l i s h h u m o u r was rather u n n a t u r a l , forced, b a t i v e N a t u r e a n d I n d i a n s , t o be o p t i m i s t i c , o r a t a l w a y s r e f l e c t i v e a n d e v e n p h i l o s o p h i c a l , b u t n o t i m p u l s i v e ; i t is, u n l i k e t h e h u g e l a u g h t e r of A m e r i c a n l e a s t to p r e t e n d t o b e o p t i m i s t i c , w a s c o n s i d e r e d a h u m o u r , a s m i l e d e c i d e d l y s a r d o n i c , w h i c h is s t i l l p a r t m o s t c o u r a g e o u s , a n d t h e p l a y of h u m o u r w a s a f r a i d t o lose i t s p r i d e of a r i s t o c r a t i c s c h o l a r l i n e s s ; c e r t a i n l y t h e best a n d m o s t sensible s e l f - p r o t e c t i o n its fear o f d e m o c r a t i c o p e n - m i n d e d n e s s m a k e s i t from m o r a l degeneration. B u t i f we can say t h a t unnecessarily lonely a n d sad. I have m a n y a reason t h e r e a l t r o u b l e w i t h t h e present A m e r i c a n s lies i n n o t h i n g b u t t h e i r o p t i m i s m , n o u r i s h e d b y t h e i r n o w t o say t h a t t h e i m p o r t a t i o n of t h e s o - c a l l e d A m e r i c a n h u m o u r i n t o E n g l a n d w i l l d o a great h a s t y belief i n h u m a n i t y a n d carelessly e n d o r s e d a n d e n c o u r a g e d b y t h e i r n e w s p a p e r s , we w i l l h a v e s e r v i c e i n b r i g h t e n i n g u p t h e E n g l i s h life, w h i c h no h e s i t a t i o n t o s a y t h a t t h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r has b e e n depressed a n d d a r k e n e d b y t h e present h a r m l e s s , doubtless, b u t often s u p e r f i c i a l a n d s l i g h t War. A n d a t t h e same t i m e I s h o u l d s a y t h a t i t is is a m e n a c e to t h e r e a l d e v e l o p m e n t of m o r a l i t y . t h e v e r y t i m e for t h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r a t h o m e t o I find i t , i n e i g h t o r n i n e cases o u t of t e n , t o be m e r e l y l e a r n to stop i t s l a u g h t e r o r j o k e ; t h i s is t h e t i m e a j o k e o r h o r s e - l a u g h n o t b a c k e d b y life's t r a g e d y t o r e m i n d t h e A m e r i c a n s to free t h e m s e l v e s f r o m t h e or t e a r s ; while such a humour, u n l i k e the E n g l i s h i l l u s i o n of a n age of o p t i m i s t i c e x t r a v a g a n z a , n o w h u m o u r w h i c h , as s o m e b o d y s a i d , w a s officially w h e n t h e y see s u c h a h u m a n t r a g e d y i n a l l E u r o p e . c r e a t e d b y Punch, has a n agreeable aspect of n o t A m e r i c a s h o u l d also enter i n t o t h e age w h e n n o p a t r o n i z i n g t h e readers, i t shows, o n t h e o t h e r h a n d , a b s o l u t e i n d e p e n d e n c e i n a c t i o n is to be t o l e r a t e d i n quite an American-like character i n forcing them t h e s o l u t i o n of t h e p r o b l e m s of h u m a n i t y a n d t h e i n t o its p e r s o n a l c o m p r e h e n s i o n o r confidence. I t is w o r l d ; h o w c a n t h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r a l o n e h o l d s i m p l e - m i n d e d because i t r a r e l y c l a i m s m o r e t h a n its o w n o l d m a s q u e r a d i n g ? A s a piece of l i t e r a t u r e l a u g h t e r ; i t is a g a i n s i m p l e - m i n d e d because i t i t s h o u l d be r u l e d b y t h e m e a n i n g of m o d e r n l i t e r a t u r e , m e r e l y l o o k s , as a n y t h i n g else i n A m e r i c a , u p o n t h e w h i c h has left r o m a n t i c i s m e v e n for t h e r e a l i s m of q u a n t i t y a n d not on the quality. I cannot take the R u s s i a n f a s h i o n ; a n d to b e c o m e t h e best l i t e r a t u r e , w o r d s s e r i o u s l y w h e n w e are t o l d t h a t t h e s o - c a l l e d of i t s o w n k i n d , i t s h o u l d l e a v e the q u a n t i t a t i v e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r is t h e p r i d e of A m e r i c a n h e a r t s ; s t a n d a r d a n d a i m a t t h e t r u e q u a l i t y . (I say t h i s besides, I h a v e seen p r o o f e n o u g h t h a t i t s effectiveness as i f I were s p e a k i n g o n q u a l i t y before q u a n t i t y for is often d o u b t f u l i n d e e d , t h e A m e r i c a n s forget a n y o t h e r phase of A m e r i c a n life.) I say t h a t t h e s o m e t i m e s t h e i r o w n p r i d e of h u m o u r q u i t e p l a i n l y . d a y s of A r t e m u s W a r d , M a r k T w a i n , B i l l N y e , e v e n H e r e i s , a m o n g m a n y others, one e x a m p l e i n t h e t h e d a y s of M r . D o o l e y a n d G e o r g e A d e , are a l r e a d y " Q u e s t i o n b e t w e e n J a p a n a n d A m e r i c a . " W e are p a s s i n g , n o t because t h e y d i d n o t , as C h e s t e r t o n p e r i o d i c a l l y t o l d of t h e w a r a n d t h e J a p a n e s e p e r i l i n d e s i r e d i n his Defence of Nonsense, represent t h e A m e r i c a n papers, y e l l o w o r w h a t n o t ; a n d t h e o t h e r a l l e g o r i c a l v i e w of t h e w h o l e u n i v e r s e o r C o s m o s , d a y w e were t o l d t h a t a c e r t a i n A m e r i c a n s e n a t o r b u t because f r o m t h e v e r y weakness of t h e i r b e i n g had declared that to have Japanese inhabitants i n too o p t i m i s t i c t h e y d i d n o t h e l p m u c h for life's C a l i f o r n i a m e a n t to k e e p a n d feed h a t e f u l spies i n spiritual d e v e l o p m e n t ; i n another w a y of saying, t h e d o m a i n . W h a t a l a c k of " t h e sense of h u m o u r " ! f r o m b e i n g r a t h e r o u t s i d e of r e a l life, t h e y d i d n o t I r e a d i n t h e first p a r t of t h e a r t i c l e " T h e M i s s i o n m a k e t h e A m e r i c a n life e i t h e r r i c h e r o r i n t e n s e r . of H u m o u r , " b y a scholarly A m e r i c a n lady, the T h e n e w h u m o u r of A m e r i c a s h o u l d n o t b e c o m e a f o l l o w i n g w o r d s : " J u s t as t h e m o s t effective w a y t h i n g t o p l a y w i t h , b u t i t m u s t be a t r u e l i t e r a t u r e t o d i s p a r a g e a n a u t h o r o r a n a c q u a i n t a n c e a n d we built with human blood and s o u l ; and it should h a v e often o c c a s i o n t o d i s p a r a g e b o t h i s t o s a y a c t to s t r e n g t h e n life's conscience a n d force, k e e p i n g t h a t he l a c k s a sense of h u m o u r , so t h e m o s t effective t h e belief t h a t a l i t e r a t u r e g r o w s m o r e perfect a n d c r i t i c i s m we c a n pass u p o n a n a t i o n is t o d e n y i t t r u e as i t g r o w s s i m p l e r . I t s h o u l d n o t , as i n t h e t h i s v a l u a b l e q u a l i t y . " I n d e e d t h e sense of h u m o u r o l d e n d a y s , be i t s office t o a m u s e p e o p l e , b u t t o is t h e m o s t v a l u a b l e q u a l i t y of one's life o r n a t i o n ; b a c k h u m a n i t y a n d life (the n a t i o n , of course) w i t h b u t w h y d o some A m e r i c a n s a t least forget t h e i r p r i d e of h u m o u r t o w a r d s us J a p a n e s e ? W h y does its o w n belief s h o u l d be i t s greatest a i m . Y o u m u s t n o t t h i n k t h a t I w i s h to m a k e h u m o u r a s y m b o l o f t h e i r sense of h u m o u r f a i l to a p p e a r w h e n i t s h o u l d w i s d o m ; w h a t I w a n t t o say is t h a t we w i s h t o appear? I t is far f r o m m y i d e a t o s a y t h a t t h e m a k e o u r s e l v e s wise e n o u g h b y i t s t h r i c e blessed A m e r i c a n h u m o u r of t h e present t i m e is b u t a sort q u a l i t y t o l a u g h o r s m i l e , as s o m e b o d y s a i d , w h e n o f r e c r e a t i o n ; b u t I s h o u l d l i k e t o say t h a t i t is we s h o u l d o t h e r w i s e be i n d a n g e r of c r y i n g . fed b y t h e u n r e a l i t y of t h e s o - c a l l e d A m e r i c a n o p t i A s I s a i d before, I do n o t b e l i e v e i n t h e A m e r i c a n m i s m , a n d i t has, n a t u r a l l y , n o f o o t i n g o n life's h u m o u r of t h e present f o r m because i t has n o t r e a l i s m i n e v i t a b l e r e a l i s m . W h a t I w a n t t o s a y is t h a t t h e for i t s b a c k g r o u n d . I n e v e r m e a n t o b r e a k t h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r needs t o be a r o u s e d t o c o n s c i o u s d e m o c r a t i c aspect of t h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r f r o m ness of itself, a n d t o b e t a u g h t a r e a l p r o p o s i t i o n t o w a r d life. E v e n i n A m e r i c a t h e age of i r r e s p o n s i b l e a n y p o i n t ; b u t as t h e m e a n i n g of A m e r i c a n d e m o c r a c y l a u g h t e r a n d o p t i m i s m is a l r e a d y p a s s e d ; t h e t i m e has c h a n g e d t o - d a y f r o m t h e c o u n t r y ' s l o s i n g t h e absolute solitariness i n contact w i t h the inevitable , h a s a r r i v e d w h e n h u m o u r also s h o u l d a c t a t r u e p a r t d i s i l l u s i o n m e n t o f t h e m o d e r n age, t h e A m e r i c a n i n life. T h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r is s t r o n g e n o u g h t o c a s t off i t s s u p e r f i c i a l e x a g g e r a t i o n , w h i c h as l i t e r a t u r e h u m o u r t o o , as a l i t e r a r y d e m o n s t r a t i o n , s h o u l d u n d e r g o t h e p r o p e r c h a n g e q u i t e n a t u r a l of t h e is r e a l l y o l d - f a s h i o n e d a n d c o w a r d l y , a n d i t is o l d e n o u g h t o l e a r n , as M e r e d i t h was h a p p y to s a y , t h e n a t i o n . T h e A m e r i c a n h u m o u r , a t least a t present, o n l y serves as a c l o w n a l o n g life's h i g h w a y . s m i l e of t h e m i n d . T a k e off y o u r c l o w n ' s p o w d e r I should like to r e m i n d the American humorist a n d p a i n t a n d become real, y o u A m e r i c a n h u m o u r , t h a t life a n d t h e w o r l d are n o t so l i g h t - h e a r t e d as i t t o steer a w i s e c o u r s e a m i d t h e g r a v e , c o n f u s e d m o r a l often s u p p o s e s ; t h e t r u e h u m o u r is b u t a n o t h e r questions. W e expect m a n y things from y o u . p h a s e of t h e r e a l t e a r l a u g h i n g l y i n t e r p r e t e d , a n d i s , W h e n I w a s s h o w n b y S i r O w e n S e a m a n of Punch let m e s a y , a t w i n sister o r b r o t h e r of t h e t e a r differ a l a r g e r o u n d t a b l e i n t h e office ( w i t h t h e c a r v e d e n t l y b o r n b y a t w i s t o f e v o l u t i o n . I w o u l d a d v i s e

26

THE

EGOIST

February 1917

the world-famous American h u m o u r that it should be m o r e serious i f i t w a n t s to act, w i t h other phases o f A m e r i c a n l i t e r a t u r e , i n s o l v i n g t h e d e s t i n y of t h e nation.

YONE NOGUCHI

Nakano, Japan.

ENVY

I E N V Y you, I envy you, a m i d the r u m b l e a n d hoot a n d of L o n d o n ' s traffic. Happy pair! Y o u r left a n d r i g h t h a n d s d r o p a n d find e a c h o t h e r a n d w r i n g each other. W h i t e in the sun f r o m h a t t o shoes, o n l y t h e p i n k of y o u r a n k l e s s h o w i n g t h r o u g h the white stockings. Straight-limbed, firm-bosomed, soft i n t h e f o l d s of y o u r b l o u s e . A n d you, O Youth, w i t h t h e f l u s h o n y o u r cheeks, i n y o u r eyes a h a p p y a d m i r a t i o n , I envy you. Y o u r h a n d s seek a n d w r i n g e a c h o t h e r ; y o u r l i m b s a t t r a c t each other through their c l o t h i n g ; and you would marry if this a n d t h a t concurred. Foolish, oh foolish! I t is n o t y o u r y o u t h , y o u r s t r a i g h t n e s s , y o u r cleanness, y o u r b l o o m , I envy; i t is y o u r v i r g i n i t y . Y o u w o u l d p a r t w i t h i t i n a b u r s t of j o y , a n d w o u l d n o t k n o w y o u r loss, perceiving it. clatter

" Well ? " " W e l l , I k n e w those people were stained w i t h crimes, I knew they were the assassins of B e l g i u m ; but I could not help a d m i r i n g . I t was so b e a u t i f u l ! T h e y marched parade-fashion i n t h a t step w h i c h is so r i d i c u l o u s ; their uniforms, a d i r t y green c o l o u r , were covered w i t h wine a n d greasefilthy! B u t a l l t h a t was lost i n their song. G r a v e songs, i n three parts, semi-religious. N o t a voice was out of tune, all were i n t i m e ; i n a w o r d , m u s i c , real music, popular tunes, b u t not v u l g a r , simple and yet learned. A n d at t h a t moment I was, I tell y o u , more wretched t h a n e v e r ! I t h o u g h t : ' W e shall be victorious, I a m s u r e : w e shall chase them from here, we shall impose peace terms w h i c h shall keep them from doing h a r m b u t that we shall never h a v e ! ' Can y o u explain to me w h y i t seems impossible to r e v i v e a popular sense of true music i n F r a n c e ? " I could not explain, but i t seems to me too evident t h a t most unfortunately he is right. Certain southern departments excepted, there is no doubt t h a t our popular soul is t o - d a y incapable of expression otherwise t h a n by unisons, a n d w h a t unisons ! Ninety-nine F r e n c h m e n out of a hundred are unable to retain a single musical phrase w h i c h m i g h t happen to be I w i l l not say complicated but a little long. . . . T h e p o p u l a r French ideal of music takes the form of the most s t u p i d l y sentimental waltz on the one hand or, on the other, of the v u l g a r nigger chorus : degradation of both joy and melancholy, i m p o tence i n serene, grave enthusiasm. . . . So m u c h also for " T i p p e r a r y " a n d t h e British musical n u l l i t y w h i c h M . Pierre M i l l e tries to e x p l a i n a w a y b y t h e s u b s t i t u t i o n of b a r b a r i t y b y c i v i l i z a t i o n an e x p l a n a t i o n w h i c h is l i k e a sortie de secours, o r a n escape f r o m a d i l e m m a .

From

the

same a u t h o r :

A l l that is terrible, and I s a y : " I t is terrible." B u t w h a t is cruellest of a l l , most humiliating, is that m y horror comes n o t from m y senses, but from m y reason, because m y nerves expected it, knew it, have worn out their capacity of suffering and r e v o l t . The refugee is not shocked by this callousness. " I a m like y o u , " he s a i d . " W h e n I came there on the w a y from H o l l a n d I was so well prepared for what I saw t h a t i t d i d n ' t touch me ; no, not i n the least, not even to see m y house fallen into the cellar. I should never have thought t h a t so much hardness of heart could be opposed to one's o w n p a i n . It's probably because the c a l a m i t y is too b i g , universal. One says to oneself: ' N o doubt, i t had to take place.' O r perhaps B u t beauty, . . . one fails to u n d e r s t a n d ; it is beyond one's grasp, like a noise d o y o u n o t feel i t u p o n y o u ? . . . which is so loud that i t stuns y o u . B u t there is one t h i n g t h a t S t r i v e to r e a c h t h e g r a p e , b u t do n o t p l u c k i t . tears the heart, all the same. Y o u m a y have seen e v e r y t h i n g T h e g e s t u r e is a l l . without weeping ; but that must move y o u to tears. F . S. F L I N T " O h ! it is nothing, nothing at a l l . One blushes t h a t i t should so impress one. . . . I don't need to tell y o u t h a t i n t h a t country every one has a dog : these for sport or as pets, those as watch-dogs. A n d they have stayed i n the t o w n , these dogs,, PASSING PARIS when the inhabitants fled or were s h o t ; they have stayed i n a A P A S S A G E f r o m M . P i e r r e M i l l e i n his c h a r m i n g town where not a single stone is i n its place. H o w they keep alive, how they do not die of starvation, I cannot tell y o u . N o En Croupe de Bettone (Crs, 1 fr. 25) : doubt they do their o w n hunting, catch rats, scour the c o u n t r y . " Y o u ' r e not cross w i t h me at least, are y o u ? " B u t they return as fast as they can a n d a l l group together a t " A n d w h y should I b e ? " the entrance to the town, on the road. " F o r being a refugee. F o r a refugee, I m a y tell y o u , is a " T h e r e may be two hundred of t h e m , perhaps threehounds, m a n w h o sits d o w n a t y o u r table, who eats as though he had spaniels, sheep-dogs, terriers, even lapdogs, t i n y r i d i c u l o u s a n i m a l s ; and they wait, w i t h their heads turned i n the same been fasting for a fortnight, and sometimes he m a y have been. direction w i t h a look of intensely sad and passionate interest. A n d w h o says a f t e r w a r d s : ' A h ! I don't feel at home.' . . . " W h a t they are expecting is easy to understand. Sometimes one H e was full of energy, certain of victory. T h e home, the works, of the former citizens of the t o w n makes u p his m i n d a n d comes w o u l d be rebuilt. Things would go well after the warbusiness back from H o l l a n d . T h e longing to see his c o u n t r y , to find w o u l d be better t h a n ever. A n d w i t h the businesslike manner out what has been made of his house, to rout among the r u i n s , n a t u r a l to his compatriots he pointed out what would have to is stronger than everything, t h a n fear or hatred. A n d sometimes be done to set things going again. B u t suddenly he interrupted i t happens that one of the dogs recognizes him. H i s d o g ! If himself : y o u could see t h a t ! Could y o u but imagine i t ! T h i s flock of " D ' y o u k n o w w h a t m o v e d me most, what w o n ' t leave m y dogs, w i t h ears pointing as far as they can, see a m a n o n the r o a d head?" from H o l l a n d , a m a n w i t h o u t a helmet, not i n uniform. T h e p a i n " N o . T h e ruins, the fires, the b o m b a r d m e n t ? " ful anxiety, the motionless anxiety of a l l these staring beasts, " I t should be that. A n d yet i t is something else. . . . I a m staring as hard as they candogs have not v e r y good eyes almost ashamed to o w n u p to i t , i t is almost t r i v i a l . . . i t was and who scent, scent at a long distance, because their noses when they came i n , those G e r m a n s ! T h e y sang. . . . "

February 1917

THE

EGOIST

t o - d a y l i k e t h a t of K e a t s i n a preceding epoch. he w i l l be mentioned.

27

The point is,

are better t h a n their eyes. A n d at last the leap, the great leap, of one of these dogs when i t has smelt its m a s t e r ; its w i l d , savage race o n the road, ravaged a n d furrowed b y guns a n d h e a v y m o t o r c o n v o y s ; its j o y , its joyful bark, its dancing t a i l , its s k i p p i n g paws, its l i c k i n g tongue, its whole b o d y w h i c h is one t r e m o r of j o y ! I t doesn't leave the m a n now, i t doesn't w a n t to lose h i m again. F o r a d a y , or two days, i t sticks to his back, w i t h o u t eating, a n d leaves w i t h h i m . B u t the others, w h a t becomes of t h e m ? T h e y are always on the road, always on d u t y . A n d when they see the dog leave, the dog w h i c h has at last found w h a t they w a n t always, w h a t they w a n t t i l l their last day, t h e y a l l raise their snouts i n despair a n d whine, whine for ever, w i t h great howls filling the heavens a n d w h i c h last t i l l there's n o t h i n g left o n the road. T h e n they s t o p ; b u t they don't budge. T h e y remain. T h e y hope. " A n d y o u weep, monsieur, when y o u see t h a t : y o u weep like they dofloods of tears. I beg y o u r pardon. . . . "

T h a t is t r u e . F i r s t of a l l , P o u n d w i l l be m e n t i o n e d because he is t h e b e s t - k n o w n p o e t of h i s g e n e r a t i o n . I s i t because he is t h e best p o e t ? W h o is t h e greatest F r e n c h , G e r m a n , Russian, or Italian poet t o - d a y ? O n e m i g h t a s k t h i s q u e s t i o n of t h e A c a d e m i e s , of t h e N o b e l tribunals. T h e i r answer w o u l d certainly n o t be t h e same as ours. N o t because w e s h o u l d g i v e a n o t h e r n a m e , b u t a w h o l e l i s t of names, w h e r e p r o b a b l y t h e one q u o t e d b y t h e wiseacres w o u l d n o t be f o u n d . E v e r y g o o d p o e t has a g r o u p of q u a l i t i e s w h i c h m a k e h i m a poet. Is he w h o possesses a l l those w e k n o w of t h e t r u e s t p o e t ? Is i t he w h o , l a c k i n g i n s e v e r a l , possesses a n e w q u a l i t y i n a n u n u s u a l degree? Is there a h i e r a r c h y a m o n g these q u a l i t i e s ? Is t h e r e a c e r t a i n i n f e r i o r i t y of t a l e n t for w h i c h t h e finest gifts w i l l n o t atone? D o n o t let u s t r y t o class P o u n d o r a n y o t h e r poet. B u t t h e r e is a p o i n t a t w h i c h one c a n define. W e can s a y w i t h a l i t t l e m o r e c e r t a i n t y i n w h a t degree s u c h a n d s u c h a poet has one of t h e p o e t i c q u a l i t i e s . I t r e m a i n s t o be seen w h e t h e r we are a l l agreed as t o t h e v a l u e of t h i s q u a l i t y , o r w h e t h e r i t is t h e k i n d t h a t w i l l shine o u t i n t h e woof of t h e p o e t i c f a b r i c . I f t h e n a m e of P o u n d comes i n t o a l l d i s c u s s i o n s o n a r t i t is because he has, t o a n u n u s u a l degree, c e r t a i n q u a l i t i e s , a n d t h a t a t least t w o of t h e m are very apparent, and greatly appreciated. H e is free a n d w i t h o u t r h e t o r i c n o one m o r e so. H i s v i s i o n is d i r e c t ; he does n o t use t h e i m a g e , b u t shows t h e t h i n g s t h e m s e l v e s w i t h p o w e r . T h i s is i n d e e d a q u a l i t y of t h e Imagistes. H i s independence comes f r o m t h e fact t h a t he has d u g i n t o t h e p a s t w i t h a keener m i n d , a n d m o r e p r o f o u n d l y t h a n is necessary for o r d i n a r y c u l t u r e . T h e n u m b e r o f influences he has passed u n d e r h a v e also freed h i m , a n d he has m a d e his d e p a r t u r e from t h e k n o w n w i t h rare a u d a c i t y . F o r m u l a e a n d rules n o l o n g e r l i m i t a n d c u t off his p e r s p e c t i v e s , b u t are a p r e t e x t for b r e a k i n g loose. H e does n o t respect o r i g i n a l s . H o w i n d e e d c a n a p o e t be m a d e o u t of a n y one w h o h a s n o t d e s t r o y e d o r p u l l e d d o w n e v e r y t h i n g , i f o n l y for a few h o u r s ? The poet is a sceptic m a d l y i n love, w h o wants i n spite of e v e r y t h i n g t o create h i s d r e a m , U p t o n o w P o u n d h a s b e a t e n o u t a p a t h for h i s c r e a t i o n s ; h e u p r o o t s weeds of aesthetics a n d m o r a l s ; he m a k e s one l o o k i n f r o n t , n o t t o t h e side, o r t h r o u g h a v e i l o f passive acceptance. E v e r y w h e r e his poems incite m a n t o e x i s t , to profess a b e c o m i n g e g o t i s m , w i t h o u t w h i c h t h e r e c a n be no r e a l a l t r u i s m .

I beseech y o u enter y o u r life. I beseech y o u learn to say " I " W h e n I question y o u . F o r y o u are no part, but a whole ; N o portion, but a being.

T o be also e s p e c i a l l y r e c o m m e n d e d i n t h i s collect i o n : La Mort du Gentleman, w h e r e i n i t is s h o w n t h a t c o n s c r i p t i o n m a k e s a n e n d of t h a t p e c u l i a r l y British speciality.

T h e P r i x G o n c o u r t has been a w a r d e d t o M . H e n r i B a r b u s s e , whose L'Enfer w a s r e v i e w e d i n these c o l u m n s last year. F e w , if any, other E n g l i s h publications h a d , I believe, dealt w i t h i t . S i n c e t h e n M . B a r b u s s e has p u b l i s h e d Le Feu, w h i c h o b t a i n e d t h e p r i z e . T h e a t t r i b u t i o n for 1914 has n o t y e t been v o t e d .

T h e d e a t h has o c c u r r e d of Thodule R i b o t , t h e philosopherwho resented being thus qualified a u t h o r of L ' A t t e n t i o n , Les Maladies de la Volont, Les Maladies de la Mmoire, etc., w h i c h w e n t t h r o u g h as m a n y e d i t i o n s as p o p u l a r n o v e l s . O t h e r of h i s w o r k s s t u d i e d the Passions, t h e Logic of Sentiments, t h e Creative Imagination. Thodule R i b o t d i s c o v e r e d two new principles : psycho-physiology a n d psychop a t h o l o g y w h i c h discoveries f o u n d e d a s c h o o l of i n v e s t i g a t o r s . H e r e a l i z e d t h a t t h e s t u d y of t h e u n h e a l t h y c o n d i t i o n was as essential i n p s y c h o p h i l o s o p h i c a l research as the s t u d y of t h e h e a l t h y form. M . C.

EZRA POUND

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF J E A N DE

BOSSCHRE

II NOW w e c o m e t o t h e Lustra of E z r a P o u n d . I t is t h e m o m e n t t o get a w a y f r o m m y s e l f a n d ask w h a t o t h e r p e o p l e t h i n k a b o u t P o u n d . W h a t p o s i t i o n has he i n t h e c r o w d of p o e t s ? In t h e " p o r t r a i t " of P o u n d I s k e t c h e d o u t a n a p p r e c i a t i o n of h i s w o r t h , b u t M r . C a r l S a n d b u r g has l o o k e d a t t h e p o e t ' s w o r k f r o m a g r e a t d i s t a n c e f r o m across t h e A t l a n t i c . H i s j u d g m e n t is c o n c e r n e d r a t h e r w i t h t h e w o r k o r t h e a t t i t u d e of t h e m a n t h a n w i t h the m a n himself. M r . S a n d b u r g writes :

If I were d r i v e n to name one i n d i v i d u a l who, i n the E n g l i s h language, b y means of his o w n examples of creative art i n poetry, has done most of l i v i n g men to incite new impulses i n poetry, the chances are I w o u l d name E z r a P o u n d . T h i s statement is made reservedly, out of k n o w i n g the w o r k of P o u n d a n d being somewhat close to i t three years or so. . . . If, however, as a friendly stranger i n a smoking c o m p a r t m e n t , y o u s h o u l d casually ask me for a n off-hand o p i n i o n as to who is the best m a n w r i t i n g poetry to-day, I should p r o b a b l y answer, " E z r a P o u n d . " A l l t a l k o n modern poetry, b y people w h o k n o w , ends b y dragging i n E z r a P o u n d somewhere. H e m a y be n a m e d o n l y to be cursed as w a n t o n a n d mocker, poseur, trifler, a n d v a g r a n t . O r he m a y be classed as filling a niche

T h a t a t least is t h e i l l u s i o n h e gives a t m o m e n t s w h e n one w a n t s t o see t h e w o r l d as a p o e t ; t h a t i s t o say i n one's m o s t l u c i d a n d h u m a n m o m e n t s . O n e m u s t b e l i e v e i n one's o w n e x i s t e n c e , a n d t h i s f a i t h b e g i n s w i t h n e g a t i o n . O n e m u s t be c a p a b l e of r e a c t i n g t o s t i m u l i for a m o m e n t , as a r e a l , l i v e p e r s o n , e v e n i n face of as m u c h of one's o w n p o w e r s as are a r r a y e d a g a i n s t one, b a l a n c e d b y a n i m m e d i a t e avowal :

A n d w h o are we, w h o k n o w t h a t last intent, T o plague to-morrow w i t h a testament !

B u t a k i n d of disease c a l l e d h o p e c a n n o t be c u t o u t of a m a n ' s h e a r t . H e goes o n b e l i e v i n g i n t h e successive m o m e n t s . I t is great p o e t r y , t h e i n t i m a t e d r a m a of t h i s s t r u g g l e , t o go o n b e l i e v i n g i n s p i t e of t h e a p p e a r a n c e of e m p t i n e s s . T h e groans, t h e

28

THE

poet, a l l w h i c h

EGOIST

February 1917