Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Greece Financial Crisis

Transféré par

lubnashaikh266245Description originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Greece Financial Crisis

Transféré par

lubnashaikh266245Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Greece Financial Crisis:

For years, Greece has been spending money it doesn't have. The government there took advantage of the economic good-times to borrow money and spend it on pay-rises for public workers and projects such as the 2004 Olympics. It began to run-up a bigger and bigger deficit (the gap between how much a country brings in from tax, and what it spends). After the world economy went bad, Greece suffered. Banks started to view it as a country that might not be able to manage its money. They worried Greece might eventually fail to pay its loans, and even go bankrupt. To cover the risk, banks started charging Greece more to borrow cash - making the problem even worse. Eventually the government there went looking for help. It is now borrowing 110 billion euros (95bn) from other EU countries and the International Monetary Fund. That money is being loaned at a much better rate, but comes with tough conditions. Greece has to promise to cut its budget deficit. It's those cuts that have led to the riots in Athens. What does this mean for other countries? As well as Greece, banks and credit rating agencies are going through their books looking for other bad risks. That means countries that have a big budget deficit, compared with how much money their economy generates. Portugal and Spain are reckoned to be two that could face problems next. The EU hopes that its bailout will reassure the money markets that their cash is safe. However, that depends on Greece getting control of the situation and proving it can make the cuts needed. The UK does not use the Euro currency, but could still be affected. Its budget deficit is also large, and we could start to appear unattractive to lenders. UK banks also hold some of the debt of countries such as Greece, Spain, and Portugal. If they were to go bankrupt, it would mean more problems for Britain's banks.

In the mean-time, there is some good news for holidaymakers. A fall in the value of the Euro means the pound currently goes a bit further at the bureau de change. Why is Greece in trouble? Greece was living beyond its means even before it joined the euro. After it adopted the single currency, public spending soared. Public sector wages, for example, rose 50% between 1999 and 2007 - far faster than in other eurozone countries. And while money flowed out of the government's coffers, its income was hit by widespread tax evasion. So, after years of overspending, its budget deficit - the difference between spending and income - spiralled out of control. When the global financial downturn hit, therefore, Greece was ill-prepared to cope. Debt levels reached the point where the country was no longer able to repay its loans, and was forced to ask for help from its European partners and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the form of massive loans. In the short term, however, the conditions attached to these loans have compounded Greece's woes. What has been done to help Greece? In short, a lot. In May 2010, the European Union and IMF provided 110bn euros ($140bn: 88bn) of bailout loans to Greece to help the government pay its creditors. It soon became apparent that this would not be enough, so a second, 130bn-euro bailout was agreed earlier this year. As well as these two loans, which are made in stages, the vast majority of Greece's private creditors agreed to write off more than half of the debts owed to them by Athens. They also agreed to replace existing loans with new loans at a lower rate of interest. However, in return for all these loans, the EU and IMF insisted that Greece embark on a major austerity drive involving drastic spending cuts, tax rises, and labour market and pension reforms. These have had a devastating effect on Greece's already weak economic recovery. The European Commission expects the Greek economy to shrink by another 4.7% this year. Greece has already been in recession for four years. Without economic growth, Greece cannot boost its own income and so has to rely on aid to pay its loans. Many commentators believe even the combined 240bn euros of loans and the debt write-off will not be enough. What happens next?

The result of the general election on 17 June was greeted with relief in eurozone capitals, the EU and IMF. The win for New Democracy has, for the time being, eased fears that Greece is about to leave the eurozone. Yet major problems remain and the financial markets are still nervous. It Greece's economy continues to contract sharply, the country may not be able to repay its debts, meaning it will need further help. If the rest of Europe is no longer willing to provide it, then Greece may be forced to leave the euro. There is, of course, the possibility that the Greek people, fed up with rising unemployment and falling living standards, will make it impossible for the government to continue with austerity. However, European leaders are hoping that the Greek economy will slowly begin to recover, thanks to the wide-ranging reforms insisted upon by the EU and IMF, allowing Greece to make its repayments and once again, stand on its own two feet. Why does this matter for the rest of Europe? It matters a lot. If Greece does not repay its creditors, a dangerous precedent will have been set. This will make investors increasingly nervous about the likelihood of other highly-indebted nations, such as Italy, or those with weak economies, such as Spain, repaying their debts. If investors stop buying bonds issued by other governments, then those governments in turn will not be able to repay their creditors - a potentially disastrous vicious circle. To combat this risk, European leaders have agreed a 700bn-euro firewall to protect the rest of the eurozone from a full-blown Greek default. Equally, if banks that are already struggling to find enough capital are forced to write off money over and above that which they have already agreed to, they will become weaker still, undermining confidence in the entire global banking system. Banks would then be even more reluctant, and less able, to lend to one another, potentially sparking a second credit crunch, where bank lending effectively dries up. For example, Greece owes French banks $38bn, German banks $5.5bn, UK banks $8.2bn and US banks $3.5bn. This problem would be exacerbated by savers and investors taking money out of banks in vulnerable economies, such as Greece, Portugal and Spain, and moving it to banks in safer economies such as Germany or the Netherlands. This could lead to more banks defaulting on their loans. These potential scenarios would be made immeasurably worse if Greece were to leave the euro. The country would almost certainly reintroduce the drachma, which would devalue dramatically and quickly, making it even harder for Greece to repay its debts. (2010 info):

So what is Greece doing? As already mentioned, the government has started slashing away at spending and has implemented austerity measures aimed at reducing the deficit by more than 10 billion ($13.7 billion). It has hiked taxes on fuel, tobacco and alcohol, raised the retirement age by two years, imposed public sector pay cuts and applied tough new tax evasion regulations. Are people happy with this? Predictably, quite the opposite and there have been warnings of resistance from various sectors of society. Workers nationwide have staged strikes closing airports, government offices, courts and schools. This industrial action is expected to continue.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Impending Monetary Revolution, the Dollar and GoldD'EverandThe Impending Monetary Revolution, the Dollar and GoldPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary and Analysis of The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe: Based on the Book by Joseph E. StiglitzD'EverandSummary and Analysis of The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe: Based on the Book by Joseph E. StiglitzÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (3)

- Greece CrisisDocument6 pagesGreece CrisisShu En SeowPas encore d'évaluation

- Q&A: Greek Debt Crisis: What Went Wrong in Greece?Document7 pagesQ&A: Greek Debt Crisis: What Went Wrong in Greece?starperformerPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Crisis Explained: Why Is Greece in Trouble?Document3 pagesEurozone Crisis Explained: Why Is Greece in Trouble?devilcaeser2010Pas encore d'évaluation

- National Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument15 pagesNational Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt Crisisalok mishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece Debt Crisis ExplainedDocument4 pagesGreece Debt Crisis ExplainedLee SharpPas encore d'évaluation

- The European Debt Crisis: HistoryDocument7 pagesThe European Debt Crisis: Historyaquash16scribdPas encore d'évaluation

- Uni EropaDocument5 pagesUni Eropadiandra aditamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece Economic CrisisDocument5 pagesGreece Economic CrisisPankaj Kumar SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece's Debt Crisis ExplainedDocument6 pagesGreece's Debt Crisis ExplainedNgurah MahendraPas encore d'évaluation

- What's The Latest?: Greece Debt Crisis Alexis Tsipras International Monetary FundDocument6 pagesWhat's The Latest?: Greece Debt Crisis Alexis Tsipras International Monetary FundsrpvickyPas encore d'évaluation

- Debt CrisisDocument8 pagesDebt CrisisUshma PandeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Government Debt CrisisDocument8 pagesGreek Government Debt CrisisShuja UppalPas encore d'évaluation

- Greek Financial Crisis May 2011Document5 pagesGreek Financial Crisis May 2011Marco Antonio RaviniPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief On GreeceDocument4 pagesBrief On GreeceHarsha RavuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Crisis and Its Impact On Indian Economy 4800 +Document16 pagesEurozone Crisis and Its Impact On Indian Economy 4800 +Bhavesh Rockers GargPas encore d'évaluation

- Stability Fund Is Not Very StableDocument4 pagesStability Fund Is Not Very StableNaimul EhasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Investment Loans Greece-EU-IMF. Is Is Fair?: How It Started?Document4 pagesInvestment Loans Greece-EU-IMF. Is Is Fair?: How It Started?Rusu CalinPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece's Mismanagement of Fiscal PolicyDocument5 pagesGreece's Mismanagement of Fiscal PolicyShrey ChaudharyPas encore d'évaluation

- RMF July UpdateDocument12 pagesRMF July Updatejon_penn443Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01Document9 pagesPaper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01290105Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalDocument4 pagesVinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalFinterestPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Is Greece in Debt?Document5 pagesWhy Is Greece in Debt?yatz24Pas encore d'évaluation

- Euro Debt CrisisDocument2 pagesEuro Debt CrisisAmrita KarPas encore d'évaluation

- Eco 1Document2 pagesEco 1night2110Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Document4 pagesThe Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Qraen UchenPas encore d'évaluation

- Greec Crisis Causes&ImplicationDocument9 pagesGreec Crisis Causes&Implicationshubh_sumanPas encore d'évaluation

- It Is All Greek, Then Now and How?: Euro Currency Adoption: The Adoption of A Common Euro Currency Had ADocument3 pagesIt Is All Greek, Then Now and How?: Euro Currency Adoption: The Adoption of A Common Euro Currency Had APranav AnandPas encore d'évaluation

- European Debt CrisisDocument3 pagesEuropean Debt CrisisVivek SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Round 3 DebateDocument3 pagesRound 3 Debateapi-344837074Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Impact of Europe Debt Crisis On The World Economy: Assignment of Banking and FinanceDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Europe Debt Crisis On The World Economy: Assignment of Banking and FinanceHồng NhungPas encore d'évaluation

- Beyond The Edge: Whatever Happens To Greece, The Failings of The Euro Zone Have Not Been AddressedDocument4 pagesBeyond The Edge: Whatever Happens To Greece, The Failings of The Euro Zone Have Not Been AddressedKarla BruniPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Debt Crisis: Causes, Timeline, Extent of The Crisis, How It Is Being Addressed and How It'Ll Affect UsDocument15 pagesEurozone Debt Crisis: Causes, Timeline, Extent of The Crisis, How It Is Being Addressed and How It'Ll Affect UsShivani SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- CRS Insights: June 29, 2015 (IN10295)Document3 pagesCRS Insights: June 29, 2015 (IN10295)testPas encore d'évaluation

- 02-10-2012 - EOTM - Der KommissarDocument3 pages02-10-2012 - EOTM - Der KommissarYA2301Pas encore d'évaluation

- Email Share Tweet Save More Continue Reading The Main Story: by The New York Times Updated November 9, 2015Document7 pagesEmail Share Tweet Save More Continue Reading The Main Story: by The New York Times Updated November 9, 2015Mozammel HoquePas encore d'évaluation

- Guide To The Eurozone CrisisDocument9 pagesGuide To The Eurozone CrisisLakshmikanth RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is The European DebtDocument32 pagesWhat Is The European DebtVaibhav JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Euro Debt CrisisDocument2 pagesEuro Debt CrisisJona CabertePas encore d'évaluation

- Fixed Income Securities: Essay AssignmentDocument3 pagesFixed Income Securities: Essay AssignmentSheeraz AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- Debt Crisis in GreeceDocument6 pagesDebt Crisis in Greeceprachiti_priyuPas encore d'évaluation

- European Union Moves To Put Out Greek Fire: Economics GroupDocument3 pagesEuropean Union Moves To Put Out Greek Fire: Economics Groupelise5351Pas encore d'évaluation

- Euro Zone Crisis - A Global Problem - The HinduDocument3 pagesEuro Zone Crisis - A Global Problem - The Hindurajupat123Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Greek TragedyDocument6 pagesThe Greek TragedyGRK MurtyPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Implication 1Document25 pagesEurozone Implication 1JJ Amanda ChenPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece Crisis Greece Crisis: A Tale of Misfortune A Tale of MisfortuneDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis Greece Crisis: A Tale of Misfortune A Tale of MisfortuneSmeet ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- EUs Financial CrisisDocument35 pagesEUs Financial CrisisUmar Abbas BabarPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece Crisis and The Consequences For IndiaDocument4 pagesGreece Crisis and The Consequences For IndiaAditya KharkiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Article For Greece-Fields EconomicsDocument13 pagesArticle For Greece-Fields EconomicsΜαρινα ΜαστρογιαννοπουλουPas encore d'évaluation

- Financial Crisis 2Document4 pagesFinancial Crisis 2Arul SakthiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bringing Greece Back To Growth: A Third Assistance Programme For GreeceDocument3 pagesBringing Greece Back To Growth: A Third Assistance Programme For GreeceEconomy 365Pas encore d'évaluation

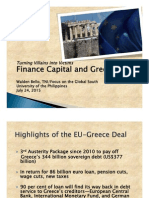

- W. Bello: Turning Villains Into Victims Finance Capital and GreeceDocument35 pagesW. Bello: Turning Villains Into Victims Finance Capital and GreeceGeorge PaynePas encore d'évaluation

- European Sovereign Debt Crisis: PiigsDocument11 pagesEuropean Sovereign Debt Crisis: PiigsBismahqPas encore d'évaluation

- Greece DebtDocument2 pagesGreece DebtChetan MittalPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Crisis: Impacts: Prepared ForDocument24 pagesEurozone Crisis: Impacts: Prepared ForAkif AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Happening in The Euro Area-1Document3 pagesWhat Is Happening in The Euro Area-1BruegelPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 5bDocument20 pagesGroup 5bAnkit SinghviPas encore d'évaluation

- Abandon Ship: Time To Stop Bailing Out Greece?: by Raoul Ruparel Edited by Stephen Booth and Mats PerssonDocument23 pagesAbandon Ship: Time To Stop Bailing Out Greece?: by Raoul Ruparel Edited by Stephen Booth and Mats PerssonVango StavroPas encore d'évaluation

- Eurozone Debt Crisis Recap: September 14 2011Document17 pagesEurozone Debt Crisis Recap: September 14 2011crazykid9Pas encore d'évaluation

- Yahoo Symbol ListDocument21 pagesYahoo Symbol ListShubham RohatgiPas encore d'évaluation

- TeamNews n70 ANG PDFDocument9 pagesTeamNews n70 ANG PDFkaren stefania hortua curzPas encore d'évaluation

- Wage Account November 2020M HN-1Document12 pagesWage Account November 2020M HN-1Pavel ViktorPas encore d'évaluation

- Reconciliation Statement MathDocument6 pagesReconciliation Statement MathRajibPas encore d'évaluation

- Ascon NodeDocument2 pagesAscon NodeMuhammad WaseemPas encore d'évaluation

- RFP For Consultant 3rd ParallelDocument115 pagesRFP For Consultant 3rd ParallelNaim ParvejPas encore d'évaluation

- WP2310Document24 pagesWP2310Nick FaldoPas encore d'évaluation

- $834.67 Discount BondDocument5 pages$834.67 Discount BondLưu Gia Bảo0% (1)

- The Evolution of Islamic Finance in MalaysiaDocument3 pagesThe Evolution of Islamic Finance in MalaysiaNURUL AMALINA BINTI ROSLI STUDENTPas encore d'évaluation

- EMI Calculator - Ankur WarikooDocument15 pagesEMI Calculator - Ankur WarikooKshitij BishtPas encore d'évaluation

- Assam Economic SurveyDocument232 pagesAssam Economic SurveyBarna GanguliPas encore d'évaluation

- Gyan Ganga: Institute of Technology &sciencesDocument6 pagesGyan Ganga: Institute of Technology &sciencesMandhir NarangPas encore d'évaluation

- Ingles Cuestionario Quimestre 2-1Document3 pagesIngles Cuestionario Quimestre 2-1Ana AlvaradoPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 7 Week 8 - Intro To Portfolio TheoryDocument24 pagesWeek 7 Week 8 - Intro To Portfolio TheoryJoshua NemiPas encore d'évaluation

- Diffusion Aceleration and Business Cycle Hickman 1959Document32 pagesDiffusion Aceleration and Business Cycle Hickman 1959Eugenio MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Table 13.2 Valuation Template 8Document2 pagesTable 13.2 Valuation Template 8Henry S. ChoiPas encore d'évaluation

- R56 Technical AnalysisDocument20 pagesR56 Technical AnalysisxczcPas encore d'évaluation

- Tybaf Sem5 Fm-Ii Nov18Document5 pagesTybaf Sem5 Fm-Ii Nov18rizwan hasmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chap 19Document14 pagesChap 19N.S.RavikumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Media Docs Bright Beginnings Fee Structure 2023Document2 pagesMedia Docs Bright Beginnings Fee Structure 2023Maureen MwendePas encore d'évaluation

- TP-WMS-05816-DAS-A4-D1-L - Swing Check Valve DatasheetDocument1 pageTP-WMS-05816-DAS-A4-D1-L - Swing Check Valve Datasheetbmanojkumar16Pas encore d'évaluation

- CH 16Document12 pagesCH 16Islani AbdessamadPas encore d'évaluation

- Dhirubhai AmbaniDocument73 pagesDhirubhai AmbaniVireksh PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- 45PV Promo Order July 2023Document1 page45PV Promo Order July 2023Marques Da DeolindaPas encore d'évaluation

- MHR 520 Note (Aiden)Document18 pagesMHR 520 Note (Aiden)hanhvy04Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Crowding Out Effect How Does It Affect EconomiesDocument3 pagesWhat Is Crowding Out Effect How Does It Affect EconomiesAjinath DahiphalePas encore d'évaluation

- TYBBA (IB) (Sem V)Document11 pagesTYBBA (IB) (Sem V)ANUSUYA CHATTERJEEPas encore d'évaluation

- Vacancies For Management Trainees211218Document6 pagesVacancies For Management Trainees211218udiptya_papai2007Pas encore d'évaluation

- GSIS TEMPLATE Fire Insurance Application Form (TRAD)Document3 pagesGSIS TEMPLATE Fire Insurance Application Form (TRAD)Ronan MaquidatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Birdflu 666Document934 pagesBirdflu 666sligomcPas encore d'évaluation