Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

0807 Lang Katalin

Transféré par

Joseph Ignatius LingCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

0807 Lang Katalin

Transféré par

Joseph Ignatius LingDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, Volume 4 Number 1 2009

THE ROLE OF STORYBOOKS IN TEACHING ENGLISH TO YOUNG LEARNERS

Katalin LNG

(Vitz Jnos Catholic College, Esztergom, Hungary)

langkata@freemail.hu

The first part of this paper gives a short background to the theoretical assumptions of early foreign language teaching focusing on the term CPH (Critical Period Hypothesis).The second part briefly looks at the theoretical underpinning of using literature as a resource for language teaching. The last section introduces the reader to two projects incorporating stories into the practice of the classroom. Keywords: teaching, language teaching, foreign language teaching, English teaching

Young learners and second language acquisition

The definition of the term: critical period hypothesis

One of the most hotly debated issues in second language acquisition (SLA) research is the critical period hypothesis (CPH). The term was originally proposed by two neurobiologists, Penfield and Roberts, but it is Lenneberg whose name is widely associated with it (see in Hakuta & Bialystok & Wiley, 2003). The critical period hypothesis states that "there is a specific and limited time period during which language acquisition is easy and complete... and beyond which it is difficult and typically incomplete" (Ellis, 1998:67). Two additional points need to be mentioned: first, according to DeKeyser and Larson-Hall (2005), this hypothesis applies to both first and second language acquisition. Second, instead of the term critical, sensitive and optimal have also been used by several authors representing slightly different interpretations as compared to the original one, but the term critical has spread in the literature. (See the list of authors representing the different usage of the term in Nikolov, 2000:16.) Debates have been going on into the notion of the CPH: several researchers have been attracted by it, arguing for and against the existence of CPH. Four different major standpoints exist in the literature which illustrates this uncertainty (Nikolov, 2000). The so called 'younger the better', the strong version of CPH, states that young children are generally more successful than older learners, only they can acquire native-like pronunciation, and after puberty a decline in SLA capacity begins. It is based on the public wisdom according to which children pick up the language quickly and easily when they are exposed to it. (Hakuta & Bialystok & Wiley, 2003; Singleton, 2001).The proponents of the second standpoint, 'the older the better' version claim just the opposite of the above mentioned one: late beginners have a faster acquisition rate, therefore they are more efficient language learners. Studies on primary school SLA, successful adult learners

47

LNG, K.: The Role of Storybooks in Teaching English..., p. 47-54.

and immersion programmes seem to support their view (Harley& Hart, 1997; Ioup & Boustagui & Tigi & Moselle, 1994). The third standpoint, 'the younger the better in some areas', the weak version of CPH, states that children are better only in the area of pronunciation. Finally, 'the younger the better in the long run' version assumes that, despite the initial advantages of adult learners in some areas, such as syntax and morphology, children can overtake adults in the long run achieving better results (Nikolov, 2000). To sum up this review, although there is not sufficient evidence for the existence of CPH, the claim that there is an age-related decline regarding the success of achieving native-like proficiency in SLA seems to be supported. Further research needs to be carried out, with a special focus on pedagogical, psychological and sociological variables.

Arguments for early second language teaching

However controversial the results of research are, there is some evidence which support the existence of CPH, therefore they can not be neglected when we argue for early foreign language education. Arguments for the introduction of early foreign language programmes in formal instruction can be grouped under four major headings: (1) cognitive reasons (2) neurological reasons (3) linguistic reasons and (4) social-psychological reasons.

Explanations

The cognitive explanation

There are several age-related changes in cognitive processes which underpin early foreign language teaching. Working memory capacity, cognitive processing speed, risk-taking, the ability of encoding new information and recalling details, all decline with ageing (Hakuta & Bialystok & Wiley, 2003). Based on the research in cognitive science, children favour implicit (procedural) learning - which is rather slow and requires intensive input and interaction- and mostly rely on their memory. Adults, however, tend to prefer explicit (declarative) learning and rely on their analytical abilities during SLA (DeKeyser & Larson-Hall, 2005). Harley and Hart (1997) also describe this phenomenon, differentiating between wholist (characteristic of children) and analytic (typical for adults) approaches in processing information. Although the difference between implicit and explicit learning does exist, it mainly has pedagogical implications, and does not prove children's success at SLA. An additional argument for children's superiority at SLA is described in Hyltenstam's and Abrahamsson's study (2003:565): "Adult learners differ from child learners in that they no longer have access to the inborn language acquisition device [LAD - introduced in Chomskyan theory)] specified in UG [Universal Grammar] and instead have to rely on general problemsolving procedures".

The neurological explanation

Since Penfield's and Roberts's publication on CPH, there have been biological explanations for children's greater success in language acquisition. They argued for the brain's steady loss of flexibility and cerebral plasticity "the ability of neurons to make new connections"- with ageing (Hyltenstam & Abrahamsson, 2003:561).

48

Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, Volume 4 Number 1 2009

Lenneberg referred to the process of laterization of the brain, during which the right and the left hemispheres become specialized, which happens around puberty, causing difficulties in language acquisition afterwards (see in Nikolov, 2000). Neuroscience is a rapidly growing division of learning, more and more studies are dedicated to the investigation of the nature of language acquisition (Singleton, 2001).

The linguistic explanation

Linguistic arguments regarding the age factor in SLA, mainly emphasize the role of environmental input children and adult experience. On the one hand, adults are likely to receive quantitatively less input, and qualitatively more complex input. On the other hand, children are provided with more input and less-complex, strongly simplified language from their caretakers (DeKeyser & Larson-Hall, 2005). This phenomenon probably also contributes to children's better attainment in the long run. Considering the amount of input, several studies examined the influence of age of arrival and length of residence on learners' achievement in their host environment.

The social-psychological explanation

Several variables are listed by DeKeyser and Larson-Hall (2005) as predictors of success in SLA. Among these factors are integrative motivation, self-consciousness, risk-taking, attitude toward and identification with the target community and culture. What enhances children's success in SLA is their inherent motivation, their readiness to communicate and thus understand the world around them, and their lack of fear of making mistakes. Krashen's Affective Filter Hypothesis (1985) tries to give an explanation for children's low level of anxiety. He states that the affective filter is a mental block which prevents learners from using the input. If the acquirer is anxious and unmotivated, the filter is 'up', the input will not reach LAD. Krashen hypothesised that around puberty the effect of the affective filter gets stronger, which would explain the better achievements of young learners in SLA. Considering the differences between young and older arrivals in a L2 environment regarding the level of the identification with the target community, the advantages of young learners seem evident. Because of their compulsory schooling, they more easily integrate into the target culture and acquire L2. Also, as their cultural and linguistic identity is less fully formed as compared to late arrivals, young learners' motivation to maintain their L1 is weaker (Singleton, 2001).

Early foreign language programmes

In the previous passages I have introduced the notion of CPH and outlined the major arguments for early second language teaching. The aim of the next step in this chapter is to give a short summary of the tradition of early foreign language programmes. By way of introduction I would like to clarify the difference between immersion programmes and foreign language (FL) programmes. In the settings of immersion education (originating from Canada) the target language of education is the one that is widely used in the social environment of learners; whereas in case of FL programmes, the usage of the

49

LNG, K.: The Role of Storybooks in Teaching English..., p. 47-54.

target language is mainly limited to the classroom, therefore it is not used in learners' everyday life. While in immersion programmes the target language is a medium of instruction partly or totally, in FL programmes it is taught as a school subject. Considering the overall picture of early FL instruction, there has been a radically increasing interest in it in the past two decades all over the world. The publication of Nikolov & Curtain (2000) compiles eighteen studies introducing early FL practice from many different countries. Despite the fact that the contexts of these educational programmes differ to a great extent, they have one thing in common: they all accept and follow the assumption 'the younger the better' in their programme design. In her study, Nikolov (2000) calls attention to the danger of lack of continuity and transfer in early FL programmes with the suggestion of careful consideration of aims, expectations, methodology, and previous knowledge of learners. It is also worth mentioning the results of the workshop in 1996 held in ECML (European Centre for Modern Languages, Graz) being dedicated to the issue of early foreign language learning. A group of international experts concluded their meeting by formulating some broad implications for early FL programmes. They derived their list of suggestions from the above theories: "Learning should be child-centered and experiential Children should be encouraged to be active and constructive in their own learning Learning should involve social interaction Language should be used as a tool to do things which are relevant and meaningful to the child Activities and tasks should present an appropriate level of challenge Effective "scaffolding" or "mediation" should be available to support learning Children should have lots of opportunities to extend learning through related activities and tasks Abstract, formal reflection on language should come after practical, concrete experience of using language" (Read & Ellis, 1996:4). In my opinion, it would be instructive and informative to conduct more classroom-based research in order to reveal to what extent the curriculum design and FL classroom practice, such as methodology and choice of materials, is based on the above mentioned theories and follows these suggestions. The purpose of the following section is to highlight the essence of using literature as a resource in language learning with special focus on young learners' needs.

Literature and language development

Maley (1989) makes a valuable distinction between the study of literature and the use of literature as a resource for language learning. While the former approach the text as a cultural piece of art, the latter considers the text a language in use which can be exploited for language learning purposes (Brumfit, 1989). In this study I will focus on the second interpretation and the role of children's literature, especially storybooks in early SLA. Literature on the use of stories and picture books in young L2 learners' classrooms has been rich as educationalists are eager to develop techniques

50

Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, Volume 4 Number 1 2009

and activities suitable for the particular target group (Garvie, 1990; Ellis & Brewster, 1991, 2002; Brewster & Ellis & Girard, 2002; Mourao, 2006, among others). Literature, telling and reading stories for children, has an immense value for children, parents, teachers and educators. It plays a strong role in child language, cognitive, personal and social development both in mother tongue acquisition and SLA. It motivates and instructs at the same time. It stimulates different kinds of development, it transmits knowledge, values and believes, and it supports and expands imagination and creativity. As Collie and Slater (1987) formulate the benefits of literature for teachers: it can serve as a valuable authentic material, as a cultural and language enrichment, and above all, through working on any literary piece of work, immense opportunities are being created for learners' personal involvement.

Storybooks and the teacher

Shifting from the arguments mounted to support the idea of using literature in early foreign language education, now I am considering the ways how storybooks can be exploited in the classroom in company with their pedagogical values. To broadly define the term 'storybook' in this study, let me elicit some examples for it from the rich variety of genres of children's literature: classical fairy tales and folktales, fables, contemporary retellings of fairy tales and fables, animal stories, rhyming stories, comics, everyday life or fantasy. During the sharing experience of reading and listening to stories, audience can take up more than one subject position and learn basic concepts or facts about the world. According to Stephens (1992:162-163) 'a picture is a frozen moment in time can reveal things that words do not,can powerfully inscribe both explicit and implicit ideologies.' Stephens (1992) claims that during this process the audience will become an expert in language and in interpreting visual images. They have to decode verbal text and also understand how to read pictures. Thus using books several thinking processes like observing, comparing, and organizing can be developed. Children can recognize, find and name objects, describe colour, size, mode, emotions and generally what is happening in the picture, observe and compare details, make predictions and tell their own stories which all stimulate oral language development thus expand their vocabulary. "Moreover, since story-telling traditionally is not associated with 'learning', the 'affective filter' is low and this is also an advantage in the learning process..." (Kolsawalla, 1999:19). Stories can also motivate children to write dialogues and dramatize them, compose group stories, write a different ending to a given story, write a letter to or in the name of one of the characters. Teachers can also ask children to sequence pictures or captions of a story after the discussion of the plot. Some books are especially suitable for presenting and discussing conflicts and ways of problem-solving. Children can see examples and share solutions with each other. Adults' reading aloud serves as a model for reading and provides listening practice and also motivates children to learn to read for themselves. All in all, the ways of utilizing storybooks are inexhaustible and mainly depends on the professional experience and the creativity of the teacher. Stories, representing a theme or topic, naturally let themselves to be thoroughly exploited during series of lessons, therefore story-based language teaching in primary education has become fashionable in recent years. Further on I will introduce and summarize the results of two projects, both incorporating stories into the practice of FL classroom.

51

LNG, K.: The Role of Storybooks in Teaching English..., p. 47-54.

Introduction of two projects

The first study I would like to give account of was carried out by Lugossy and Nikolov (2003). It focuses on using authentic reading materials in lower primary FL lessons. The aim of the project was to describe and analyse how children and their teachers have benefited from using authentic books as supplementary materials. The paper also examined the effect of the project on children's siblings, peers and teachers' colleagues. Participants were children between the ages of 7-10, who had no access to English outside the classroom. The two teachers involved had different language proficiency and professional backgrounds, one working at a large, prestigious school in a city, whereas the other teaches at a small, village school with children coming from a disadvantaged socio-cultural background. During the two years of the project, teachers were given 22 richly illustrated, authentic books to read in the lessons. The special feature of the project was that children could take the books home to re-read them. Data collection has been organized using qualitative techniques: on-going self-observation by the two teachers, lesson observations by an external observer twice in the classroom, teachers' diaries and two semi-structured interviews with the teachers at the end of each school year. As for the attitudinal and motivational outcomes for children, both teachers and external observers experienced an overwhelming enthusiasm, and they claimed that it was a successful reading experience for the children. With regard to the attitudinal and motivational outcomes for teachers, both teachers reported changes in their professional lives, but in a different way. Whereas "T1 found the books "methodologically challenging", (Lugossy & Nikolov, 2003:7), T2 needed more time: at first she took the children's reading of storybooks as an occasion for her relaxation, but gradually she realized the potential that these readings provide, and felt the urge to create more interesting tasks on her own. Results show a positive influence of this project on peers and siblings, as well. Colleagues in both cases were less responsive, and parents from the rural area were more supportive and grateful as compared to parents' reactions in the city school. Further development in the area of language outcomes and group dynamics have been outlined and emphasized by the authors. The second project (Nikolov, 1998) reports on a study examining how young learners have been involved in the development of a negotiated storybased syllabus for English as a foreign language. Three groups of children between the ages of six and fourteen have been involved with the same teacher (the author) for a period of eight years in a Hungarian primary school. In the case of the first group the aim was to develop a process syllabus, whereas with the second and third group, the main goal was to pilot, assess and adapt the process syllabus to the needs of the new groups of children. During this longitudinal ethnographic-like research, several issues were observed: participation, choice of tasks and materials, assessment, the role of mother tongue, and changes in the role of the teacher. Special emphasis was given to the technique of negotiation, and its changes due to the age of children. Data was collected through the teacher's self-reflection notes. In my report on this project, I would like to focus on the issue of choice of tasks and materials. The author describes the process of negotiation on tasks and materials as follows: she offered alternatives to the children, through which children took an active part in the decision-making

52

Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, Volume 4 Number 1 2009

considering the teaching and learning process. At the same time the teacher made it clear that she was ready to listen to children's opinions, and they should be responsible for their own language development. She reports that children's decisions mainly concerned the order of tasks, and not the tasks themselves. Later children also often felt the urge to formulate their own suggestions but they were generally open to making a compromise. The author gives the following reasons for story-based language teaching: the richly illustrated authentic materials are themselves motivating for this age group, some of the tales are well-known in Hungarian as well, thus serving as a useful background knowledge for learners in the English lesson, vocabulary and language functions are presented in a meaningful context through stories, stories can be exploited by designing great variety of tasks around them, both active and passive skills are developed, Stories are excellent tools for cultural enrichment of FL teaching. During this project children were actively involved in the development of story-based syllabus: in lower primary they brought their own storybooks to the English lesson and they enjoyed listening to the same story again and again. The choice of books was based on voting. In grades 4 and 5, fewer and fewer children brought stories from home, they chose the story according to the sex of pupils or preference of topic. In grade 8 it occurred that children asked for a horror book, so the teacher offered them a choice between "Dracula", "Frankenstein" or "The Canterville Ghost". It is interesting to mention that, although they chose the third one, after finishing it, they voted for a detective story and not another horror story. In the conclusion, Nikolov states the results of the project: children's positive attitude to the English language and their success as language learners in the long run, their confidence in and sense of responsibility for language learning. As a negative outcome the lack of continuity of this innovative project is mentioned.

Conclusion

The aim of my work was to give an overview of early foreign language teaching, emphasizing the debate on the existence of critical period hypothesis (CPH). Deriving from the theoretical explanations for the introduction of early foreign language teaching I intended to summarize the assumptions and implications experts formulated for practitioner teachers. I tried to call attention to the value of literature in child development by discussing some advantages of storybooks and listing a few techniques of exploiting books in the classroom as well. In order to illustrate theory I introduced the reader to two projects which proved to be a successful realization of using storybooks in second language teaching.

53

LNG, K.: The Role of Storybooks in Teaching English..., p. 47-54.

References

BREWSTER, J. & ELLIS, G. & GIRARD, D. (2002): The primary English teacher's guide. Penguin, London. BRUMFIT, C. (1989): A Literary Curriculum in World Education. In: Carter, R. & Walker, R. & Brumfit, C. (Eds.): Literature and the Learner: Methodological Approaches. Modern English Publications and the British Council, pp. 24-29. COLLIE, J. & SLATER, S. (1987): Literature in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. DEKEYSER, R. & LARSON-HALL, J. (2005): What does critical period really mean? In: Kroll, J. F. & De Groot, A. M. B. (Eds.): Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 88-108. ELLIS, G. & BREWSTER, J. (1991): The storytelling handbook for primary teachers. Penguin, London. ELLIS, G. & BREWSTER, J. (2002): Tell it again! The new storytelling handbook for primary teachers. Penguin & Longman, London. ELLIS, R. (1998): Second language aquisition. Oxford University Press, Oxford. GARVIE, E. (1990): Story as vehicle. Multilingual Matters, Clevedon. HAKUTA, K. & BIALYSTOK, E. & WILEY, E. (2003): Critical evidence: A test of the Critical Period Hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 14, pp. 31-38. HARLEY, B. & HART, D. (1997): Language aptitude and second language proficiency in classroom learners of different starting ages. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, pp. 379-400. HYLTENSTAM, K. & ABRAHAMSSON, N. (2003): Maturational constraints in SLA. In: Doughty, C. J. & Long, M. H. (Eds.): Handbook of second language acquisition. Blackwell, London, pp. 539-588. IOUP, G. & BOUSTAGUI, E. & TIGI, M. E. & MOSELLE, M.(1994). Reexamining the critical period hypothesis: A case study of successful adult SLA in a naturalistic environment. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 16, pp. 73-98. KOLSAWALLA, H. (1999): Teaching vocabulary through rhythmic refrains in stories. In: Rixon, S. (Ed): Young learners of English. Some research perspectives. Longman, Essex, pp. 18-31. KRASHEN, S. D. (1985): The input hypothesis issues and implications. Laredo, Torrance CA. LUGOSSY, R. & NIKOLOV, M. (2003): Real books in real schools: Using authentic reading materials with young EFL learners. Novelty, 10 (1), pp. 66-75. MALEY, A. (1989): Down from the Pedestral: Literature as Resource. In: Carter, R. & Walker, R. & Brumfit, C. (Eds.): Literature and the Learner: Methodological Approaches. Modern English Publications and the British Council, pp. 10-23. MOURAO, S. J. (2006). Understanding and sharing. English storybook borrowing in Portuguese pre-schools. In: Enever, J. & Schmid-Schonbein, G. (Eds.): Picture books and young learners of English. Langenscheidt, Mnchen, pp. 49-58. NIKOLOV, M. & CURTAIN, H. (Eds.) (2000): An early start: young learners and modern languages in Europe and beyond. European Centre for Modern Languages, Strasbourg. NIKOLOV, M. (1998): ltalnos iskols gyerekek bevonsa egy trgyalsos, trtnetalap angol nyelvi tanterv kidolgozsba. Magyar Pedaggia, 98 (3), pp. 239-251. NIKOLOV, M. (2000): Issues in English language education in Hungary. Habilitation dissertation. University of Pcs, Pcs, pp. 13-60. READ, C. & ELLIS, G. (1996). Child development and early foreign language learning: implications for curriculum design, methodology and materials. Workshop No. 11/96. European Centre for Modern Languages, Graz. SINGLETON, D. (2001): Age and second language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, pp. 77-89. STEPHENS, J. (1992): Language and ideology in children's fiction. Longman, Essex.

54

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Treatise of ChamalongosDocument15 pagesTreatise of ChamalongosAli Sarwari-Qadri100% (6)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- 0 0 93853961 Training and Development in NALCO Final ReportDocument76 pages0 0 93853961 Training and Development in NALCO Final ReportSatyajeet SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Sales Force Recruitment and SelectionDocument12 pagesSales Force Recruitment and Selectionfurqaan tahirPas encore d'évaluation

- Post Modern LeadershipDocument15 pagesPost Modern LeadershipRufaida Serad100% (1)

- Counselling Skills and Techniques GuideDocument29 pagesCounselling Skills and Techniques GuideWanda Lywait100% (1)

- The Vital Role of Play in Early Childhood Education by Joan AlmonDocument35 pagesThe Vital Role of Play in Early Childhood Education by Joan AlmonM-NCPPC100% (1)

- von Hildebrand and Aquinas on Personhood vs NatureDocument62 pagesvon Hildebrand and Aquinas on Personhood vs NatureAndeanmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Across A Complete Review of Short Subjects PartDocument2 pagesAcross A Complete Review of Short Subjects PartDijattx25% (4)

- TKT Young Learners HandbookDocument27 pagesTKT Young Learners HandbookSimon Lee100% (4)

- Pnu Recommendation Form-1Document2 pagesPnu Recommendation Form-1Danilo PadernalPas encore d'évaluation

- HaileyDocument1 pageHaileyJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 Original Literary Work Declaration FormDocument1 page4 Original Literary Work Declaration FormJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Storytelling Emcee's TextDocument1 pageStorytelling Emcee's TextJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- My Simile MiniBookDocument24 pagesMy Simile MiniBookJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Task 2Document1 pageTask 2Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Fun Holiday Programme at Joy Tuition Centre: Fun and Interesting Ways To Master EnglishDocument5 pagesFun Holiday Programme at Joy Tuition Centre: Fun and Interesting Ways To Master EnglishJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

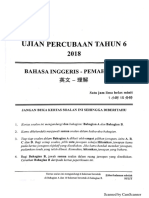

- Choose The Best Answer To Complete The Sentence.: Section ADocument9 pagesChoose The Best Answer To Complete The Sentence.: Section AJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- BB DD FF HH LL NN Oo PP RR VVWWXX ZZDocument6 pagesBB DD FF HH LL NN Oo PP RR VVWWXX ZZJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- HIP Self-Assessment Template (Auto)Document162 pagesHIP Self-Assessment Template (Auto)Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 7 Year 6 WorksheetDocument4 pagesTopic 7 Year 6 WorksheetNagarajan Pillai AboyPas encore d'évaluation

- Fun Holiday Programme at Joy Tuition Centre: Fun and Interesting Ways To Master EnglishDocument5 pagesFun Holiday Programme at Joy Tuition Centre: Fun and Interesting Ways To Master EnglishJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- In English Language AcquisitionDocument4 pagesIn English Language AcquisitionJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Year 4 SuggestedanswersDocument3 pagesYear 4 SuggestedanswersJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Upsr 2017 Paper 1Document20 pagesUpsr 2017 Paper 1Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Model 3 Paper 2Document6 pagesModel 3 Paper 2Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- UPSR SJKC Trial BI Kuching 2018Document25 pagesUPSR SJKC Trial BI Kuching 2018Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- SJK Unit 8 Unit MapDocument1 pageSJK Unit 8 Unit MapJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar Exercise: - Present Continuous TenseDocument6 pagesGrammar Exercise: - Present Continuous TenseJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- PrepositionsDocument6 pagesPrepositionsTyieara Marsya100% (1)

- AttachmentDocument2 pagesAttachmentJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Ffi '+.ffiffi: Fhe andDocument1 pageFfi '+.ffiffi: Fhe andJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunshine Round SDN BHDDocument1 pageSunshine Round SDN BHDJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Answer Scheme BI Paper 2 - TrialDocument3 pagesAnswer Scheme BI Paper 2 - TrialZamBobberPas encore d'évaluation

- Im OkDocument1 pageIm OkJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Novice To Expert How Do Professionals LearnDocument7 pagesNovice To Expert How Do Professionals LearnJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Kalen Dar Akademi K 2015Document1 pageKalen Dar Akademi K 2015Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- My Love for Singapore in 40-Char PoemDocument1 pageMy Love for Singapore in 40-Char PoemJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- HahahahaDocument1 pageHahahahaJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- 200832860 (1)Document16 pages200832860 (1)Joseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- Leadership VDocument14 pagesLeadership VJoseph Ignatius LingPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Listening Skills To Solve Customer ComplaintsDocument2 pages7 Listening Skills To Solve Customer ComplaintsmsthabetPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PraposalDocument34 pagesResearch Praposalswatisingla786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Academic Writing For Open University StudentsDocument18 pagesEffective Academic Writing For Open University StudentsErwin Yadao100% (1)

- Final Baby ThesisDocument43 pagesFinal Baby ThesisCrystal Fabriga AquinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Metaphore and Stories CBT With Childrean PDFDocument15 pagesMetaphore and Stories CBT With Childrean PDFGrupul Scolar Santana SantanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Phil1B Lec 4 The Act (Modules 5&6)Document49 pagesPhil1B Lec 4 The Act (Modules 5&6)Aryhen Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Arachnoid Cyst: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument11 pagesArachnoid Cyst: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaOsama Bin RizwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Aleppo SyriaDocument3 pagesAleppo SyriaKimPas encore d'évaluation

- New TermDocument97 pagesNew TermEthan PhilipPas encore d'évaluation

- Kunyit Asam Efektif Mengurangi Nyeri DismenoreaDocument6 pagesKunyit Asam Efektif Mengurangi Nyeri DismenoreaSukmawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Forever War Essay TopicsDocument3 pagesForever War Essay TopicsAngel Lisette LaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Emergent Futures: at The Limina of Consciousness & ComplexityDocument29 pagesEmergent Futures: at The Limina of Consciousness & Complexitymaui1100% (5)

- Mapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthDocument14 pagesMapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - Healthgamms upPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Education: Accomplishment Report On Project Reap (Reading Enhancement Activities For Pupils) S.Y. 2021-2022Document4 pagesDepartment of Education: Accomplishment Report On Project Reap (Reading Enhancement Activities For Pupils) S.Y. 2021-2022Louisse Gayle AntuerpiaPas encore d'évaluation

- LilyBlum ResumeDocument1 pageLilyBlum ResumeLily BlumPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Planning Research CentreDocument17 pagesFamily Planning Research CentreFish Man50% (2)

- Early Intervention in Children 0 6 Years With A R 2014 Hong Kong Journal oDocument9 pagesEarly Intervention in Children 0 6 Years With A R 2014 Hong Kong Journal oCostiPas encore d'évaluation

- SHELLING OUT - SzaboDocument31 pagesSHELLING OUT - Szabodeni fortranPas encore d'évaluation

- PMI EDMF FrameworkDocument2 pagesPMI EDMF FrameworkShanmugam EkambaramPas encore d'évaluation

- ValuesDocument10 pagesValuesEdsel-Stella PonoPas encore d'évaluation