Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Examen

Transféré par

Candelaria LuqueDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Examen

Transféré par

Candelaria LuqueDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE CRDOBA

FACULTAD DE LENGUAS

MAESTRA EN INGLS CURSO DE POSGRADO TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA

MA. Mara Cristina Astorga, UNRC MA. Cecilia Ferreras, UNC

Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

DNI: 27245635 Ao: 2007

Investigating learner language: comment on the essential features of Functional Analysis regarding: a. Underlying development. b. Steps for conducting a function-form analysis.

Functional analyses started to be carried out when the learners need to communicate was taken into account. In order to see underlying theories of L2 learning and L2 development, it is necessary to mention the underlying theory of language that informs this method of analysis. Language is seen as a tool for communicating meaning. Language, as Ellis and Barkhuizen (2005:111) state, is seen as a system of form-function mappings since grammatical forms are used to realize specific meanings. These mappings are complex because one form can be used to realize different meanings and one specific meaning can be realized by means of different forms. According to Ellis and Barkhuizen (2005), as multiple form-function mappings allow speakers to choose, they are the primary source of the variability found in the language. Therefore, researchers interested in investigating variability may employ functional analyses. There are underlying conceptions of L2 learning and L2 development in this approach. To begin with, learning a second language means learning linguistic structures in order to perform different functions learners are already acquainted with due to their L1 background knowledge. In Ellis and Barkhuizens (2005) words, learners bring to the task of learning an L2 an established set of functional concepts from their L1 and are driven to find appropriate linguistic means for performing these in the L2. Regarding development, we can identify stages learners go through in the acquisition of an L2. These stages of acquisition are characterized in terms of configurations of form-function mappings, which the learner reassesses and accommodates as he/she learns more about the second language. That is why, researchers supporting functional analysis, such as Huebner, Tarone and Preston, view the learners interlanguage as dynamic and variable, since learners overtime reanalyse their

conception

about

L2

learning

and

L2

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

3 mappings and bring them more closely to the mappings of a native speaker. One very interesting stage introduced by Ellis (1999) is characterized by free variation, i.e., a stage when there is no clear form-function relation between the form and meaning in the target language. Having this concept in mind, researchers can explain why learners randomly use and omit a certain linguistic form to express a specific meaning. When analysing learner language, researchers may be interested in the extent to which the mappings of the learners interlanguage match those of the target language. In order to find an answer, they may carry out a functional analysis and compare the results with the mappings found in a reference grammar. We can distinguish between two types of functional analyses: Form-function analysis and function-form analysis. On the one hand, when conducting a form function analysis, the researcher starts from a linguistic form and then investigates the meanings this form can realize in a sample of learner language. On the other hand, in a function-form analysis, the researcher selects a language function and, analysing the samples, identifies the forms that can be used to perform such function. For the purposes of this paper, the steps to carry out a function-form analysis will be presented. Ellis and Barkhuizen (2005) present the steps for conducting a function-form analysis: Identify the function of interest (semantic, semantico-grammatical, pragmatic or discourse functions). Collect samples of learner language (naturalistic or clinically elicited data). Identify the linguistic forms used to perform that function. Count the frequency of each form used to realize the function. Discover the dominant form used to realize the function of interest at a specific stage. We have seen the theories of language, L2 learning and L2 development that informs this method of analysis. Besides, the different types of functional analyses were mentioned. Finally, the steps to carry out a function-form analysis were presented.

Would you use this research approach to investigate in your L2 classrooms? Why? Why not?

Despite the fact that functional analyses can shed some light on many aspects of the learners interlanguage, I would not carry out such analyses for a number of reasons. Firstly, I am not so interested in Pragmatics as I am in Pedagogy. I am interested in the role of instruction, which in general is overlooked in this type of analysis as most studies

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

4 focus on learners acquiring a language naturally without instruction. As a teacher, I need techniques and methods which guarantee that my intervention is as useful as possible in the learning process of my students. Functional analyses can give us a glimpse of how far from the target language our students interlanguage is and what form function relations they acquire at different stages. Secondly, functional analyses do not make any reference to the role of attention in production and acquisition in order to explain variability in the language. This is closely related to the role of instruction as teachers can guide students so that their attention is focused to a certain aspect of the language. Thirdly, I myself will never reach pragmatic competence in the language I am teaching unless I live in an English speaking country long enough. That is why I do not consider myself an objective evaluator of the learners communicative/pragmatic competence, about which these types of analyses provide detailed information. To conclude, it cannot be denied that functional analyses can be very enlightening. However, it is a kind of analysis that may be of more interest to linguists than to language teachers.

What is the psycholinguistic basis of the research approach to learner language that analyses accuracy, complexity and fluency? How does Skehan s information processing model (1998) of L2 learning view storage or representation?

Researchers that are interested in analysing learners accuracy, complexity and fluency believe that learners have limited attentional resources and may attempt to one of these different aspects of an L2 when using that language. When focusing on accuracy, learners may produce language that is grammatically correct. In other words, they use the language that is fully internalised so as not to deviate from the rule system of the target language. In contrast, when complexity is the focus of attention, learners take a more creative stance towards the use of the L2 since they try to use more challenging, elaborated language. In this case, they use language that is not fully internalised because it is at the upper limit of their interlanguage systems (Ellis and Barkhuizen 2005:139). Finally, when trying to be fluent speakers, learners seek to avoid problems when communicating in order to have a task done. Meaning is prioritised. In short, certain tasks predispose the learner for fluency, complexity or

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

5 accuracy. Researchers following this approach may make use of different devices to measure accuracy, complexity or fluency. Underlying this type of analysis, there is a particular view of L2 proficiency, which has a psycholinguistic basis. Skehans information processing model has thrown some light on this research approach. He claims that the fact that attentional resources are limited has far-reaching effects on second language processing and use (1998: 73). He identifies three stages in the processing of information: input, central processing and output. Regarding input, he gives importance to the notion of noticing introduced by Schmidt, which can help account for the way in which not all input has equal value and only that input which is noticed then becomes available for intake and effective processing (Skehan, 1998: 48). Skehan adopts Schmidts proposal that a number of factors can have some influence on the way input is received. These factors include frequency and salience of certain features in the input, the role of instruction, the nature of the task, and individual differences among learners, such as readiness and processing ability. Regarding the second stage, central processing, Skehan states (1998: 86) that in order to represent or store information, learners have an information-processing dual mode system, which has a limited capacity and represents information in the form of rules and exemplars. On the one hand, the rule-based system contains rules which can be applied in creative and novel ways. The advantage of this system is that it is generative, restructurable, flexible and sensitive to feedback. The disadvantage of such a system is that operation of rule during either comprehension or production demands from the learner complex processes of construction. In Skehans (1998:31) words, it may be inadequate for the demands of realtime language processing. The exemplar-based system, on the other hand, contains examples of language which are stored as chunks or wholes. The same word may be represented many times as part of different larger units. The positive side of this system is that it is fast to be accessed during language production or comprehension. However, this system has only a limited generative potential and it is not sensitive to feedback, as this cannot produce a change that can be applied in a general way. Both modes of representation are necessary and neither is better. In other words, the rule-based system is generative and flexible, but rather demanding in processing terms, while the exemplar (memory) system may be more rigid in application, but functions much more quickly and effectively in ongoing communication (Skehan, 1998:62). These two systems should work together as neither is ideal when working in isolation. Their use depends on the different communicative contexts and purposes. For example, in ongoing

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

6 communication, when time is limited, the exemplar-based system is more appropriate as it is fast, accessible and meaning-oriented. In contrast, when the learner can spend some time to plan and prepare a particular language task in which form may be important, a rule-based system can be employed. As regards the third stage, i.e, output, Skehan believes that this system of representation explained above can be the basis for producing language. The use of the exemplar-based system, which focuses on meaning, fosters fluency while the use of the rulebased system has an impact on accuracy and complexity in the output. Although this last system focuses primarily on form, syntax is seen as a way to produce meanings. This model presented above has some teaching implications (Skehan, 1998). To begin with, without intervention, students tend to focus on meaning alone. Teachers can set up the necessary conditions so that students notice form as well as meaning. Then, teachers can manipulate processing conditions so that interlanguage change is possible. For example, students can be given time to plan before a task in carried out in order to lave less processing work during the task. During the planning phase, teachers can even channel students attention to prioritise either complexity or accuracy. This model introduced by Skehan helps distinguish between the different stages in order for teachers to know when and how intervention may be most effective for learners interlanguage to develop.

What are the essential differences between the Interaction Hypothesis proposed by Long (1988)1 and the Output Hypothesis proposed by Swain (1995)?

Before the Interaction and the Output Hypotheses were developed by Long (1983, 1996) and by Swain (1985, 1995) respectively, it was thought that acquisition of a second language was possible through natural exposure to input made up of a wide range of language samples (Krashens Comprehensible Input Hypothesis). Although the early version of Longs Interaction Hypothesis (IH) took up this idea, there was emphasis on the importance of interaction as a source of input. As Ellis and Barkhuizen (2005: 167) pointed out, since this early version of the IH was challenged on a number of fonts, it was modified so as to throw light on the role of interaction in the development and change of the learners interlanguage.

1

I could not find the relevance of this year in relation to the Interaction Hypothesis. Consequently, I decided to refer to the two versions proposed by Long in 1983 and 1996.

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

7 In both versions of the Interaction Hypothesis emphasis is placed on the fact that learners may learn a second language through interaction. Negotiation of meaning is central as it facilitates acquisition. Gass and Selinker explain that this refers to those instances in conversation when the participants need to interrupt the flow of the conversation in order for both parties to understand what the conversation is about. (2001: 272). In both versions negotiation is seen as a source of comprehensible input, i.e., while interacting, learners can receive positive evidence on what is possible in the target language. The later version incorporated the role of negative evidence and modified output. This version pointed out that negative evidence can also help learners see what is grammatical and possible in the language; i.e., while interacting, learners can receive feedback by means of recasts and therefore can compare their own deviant productions with grammatically correct input offered by the recast (Ellis and Barkhizen, 2005: 169). In Longs words, negative feedback obtained during negotiation work or elsewhere may be facilitative of L2 development, at least for vocabulary, morphology, and language-specific syntax, and essential for learning certain specifiable L1-L2 contrasts (qtd. in Gass and Selinker, 2001:294). In addition to negative evidence, the role of modified output as an important element of interaction was introduced. Long borrowed this concept from Swains Output Hypothesis, which will now be presented. The Output Hypothesis proposed by Swain suggested a crucial role for output in the development of a second language. Input alone cannot account for interlanguage development since when one hears language, one can interpret the meaning without the use of syntax (Gass and Selinker, 2001:277). In contrast, when one produces language, one has to put the elements into some order to create a coherent message. Comprehensible output refers to the need for the learner to be pushed toward the delivery of a message that is not only conveyed, but that is conveyed precisely, coherently, and appropriately (Swain, qtd, in Gass and Selinker, 2001:278). Skehan (1998) referred to three main roles for output: to test hypothesis, to force syntactic processing and to develop automaticity. Firstly, when learners produce language, they can test different hypotheses about the L2, particularly when they are given negative feedback and they modify the output so as to get closer to the target language. Students become aware of their strengths and weaknesses and they notice the gap between their interlanguage and the L2. Secondly, producing language may help learners to focus on syntax so as to convey intended meanings. Gass and Selinker (2001:290) argue that understanding the syntax of the language is a level of knowledge that is essential to the production of language. This level cannot be achieved by means of processing language only

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

8 at the level of meaning, which is done when receiving input. Thirdly, producing language helps learners to develop fluency and automaticity as the consistent and successful mapping (practice) of grammar to output results in automatic processing (Gass and Selinker, 2001:290). Therefore, learners gain control over new forms, which can be more easily accessed when needed. After presenting the main tenets of the Output and Interaction Hypotheses, we could conclude that the Output Hypothesis and both versions of the Interaction Hypothesis agree on the fact that input alone is not enough to acquire a second language. However, the first version of the IH differs from the OH in that it overlooks the function of output. Furthermore, we could say that the second version of the IH holds a similar view to the one suggested by the OH since the IH incorporates the function of output introduced by Swain. Both Long and Swain give importance to the role of output as interaction contributes to learners L2 development. The slight difference lies on the fact that Long puts emphasis on negotiation of meaning in interaction as a context for learning; whereas Swain focuses on the importance of output in that interaction.

How do Doughty and Williams (1998) deal with the implicit/explicit dichotomy in relation to FonF techniques?

One of the main concerns of English Language teaching has always been whether explicit grammar instruction should be present in the language classroom. In Long and Robinsons words: Although by no means the only important issue underlying debate over approaches to language teaching down the years, implicit or explicit choice of the learner or the language to be taught as the starting point in course design remains one of the most critical. (1998:15) In the EFL teaching history we can identify theories and approaches in the implicit and explicit extremes of the pedagogical grammar continuum. Some theorists have advocated formal and systematic attention to isolated linguistic features. Meaning is not an issue as in can be separated from grammar rules and instruction. This is the case of methods such as the Audiolingual method and the Grammar Translation method, which state that learning the language requires study of categories or parts of speech in written text and the rules for their use in translation (Hinkel and Fotos: 2002). When focusing on forms, the target language is

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

9 broken down into words and collocations, rules, structures, which are presented to the learner through pedagogical material which has been specially designed to teach the target forms (Long and Robinson, 1998:15,16). On the implicit extreme language is seen as a means of communicating ideas. There is neither explicit grammar teaching nor error correction. Language is acquired naturally in the process of real communication through exposure to samples of the language. As Hinkel and Fotos explain (2002:4), these communicative/humanistic approaches gave no formal grammar instruction but rather presented quantities of meaning-focused input containing target forms and vocabulary. This extreme seems better than a mere focus on forms. However, focusing on meaning alone may not be effective as the sole exposure to positive evidence alone is not be sufficient for the acquisition of the target language. A growing dissatisfaction with either extreme brought about a balanced approach, in which focus on grammatical features arise in a context of communicative interaction. As Long and Robinson (1998) state focus on form often consists of an occasional shift of attention to linguistic code features [...] triggered by perceived problems with comprehension or production. Focus on form (FonF) techniques can take various forms depending on the degree of the focus, the moment where the focus is placed and the nature of the target forms. One implicit technique involves teachers manipulating and enhancing the input in order to increase the perceptual salience of the target forms, which students can detect in the input without distracting them while they read (White, 1998). It has been suggested that enhancing the input together with giving extra material containing the target forms may have a positive effect on students interlanguage development. Doughty and Varela (1998) argue that implicit focus-on-form (FonF) techniques are potentially effective, since the aim is to add attention to form to a primarily communicative task rather than to depart from an already communicative goal in order to discuss linguistic feature. However, flooded input with positive evidence alone -without explicit rule explanation- may not be enough for students to progress. This is the case of contrasts between L1 and L2 forms. Another technique associated with FonF is recasting, i.e., reformulating an incorrect utterance without changing the originals meaning. Long explains that recasts are utterances that rephrase the learners utterance by changing one or more sentence components (subject, verb or object) while still referring to its central meaning (in Ellis and Barkhuizen, 2005: 169). This consists of incidental feedback on the part of the teacher showing the correct use of a certain structure. Corrective recasts involve the teacher drawing the students attention to a non-target form produced in order to offer them the correct form while they are engaged in a

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

10 communicative task. This type of feedback helps learners to draw attention to formal features without distracting them from their original communicative intent (Doughty and Varela, 1998). This technique has been claimed to be particular useful and effective in the context of content-based ESL classes. According to Doughty and Varela (1998), this relatively implicit FonF technique is task natural and reasonably incidental to teaching, as well as comfortable for the teacher. As it can be seen, different FonF techniques can be effective and advantageous depending on the complexity and nature of the target forms, the readiness of each individual learner, and the level of explicitness of focus on form (Williams and Evans, 1990).

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

11 References

Doughty, C. and E. Varela (1990) Communicative Focus on Form. In C. Doughty and J. Williams (Eds.), Focus of Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 114-138. Ellis, R. (2002) The Place of Grammar Instruction in the Second/Foreign Language Curriculum. In E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (Eds.) New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. Ellis, R. and G. Barkhuizen (2005) Analysing Learner Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gass, S.M. and L. Selinker (2001) Second Language Acquisition: an Introductory Course (2nd edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Hinkel, E. and S. Fotos (2002) From Theory to Practice: A Teachers View. In E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (Eds) New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbraum. Long, M. H. and P. Robinson (1990).Focus on Form Theory, research and practice. In C. Doughty and J. Williams (Eds.), Focus of Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 15-41. Skehan, P. (1998) A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. White, J. (1990) Getting the learners attention. A typographical input enhancement study. In C. Doughty and J. Williams (Eds.), Focus of Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 85-113. Williams, J. and J. Evans (1990) What kind of focus and on which forms?. In C. Doughty and J. Williams (Eds.), Focus of Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 139-155.

TEORAS DE LA ADQUISICIN DE UNA SEGUNDA LENGUA Luque Colombres, Mara Candelaria

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Puctuation SyllabificationDocument16 pagesPuctuation SyllabificationCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- ThinkDocument3 pagesThinkCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Selected Readings 1 FinalDocument26 pagesSelected Readings 1 FinalCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Drama Projects: Teacher's Resource BinderDocument14 pagesBasic Drama Projects: Teacher's Resource Binderperfectionlearning67% (60)

- DR JekyllDocument21 pagesDR JekyllJarir JamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Think l2Document3 pagesThink l2Candelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

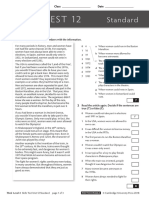

- Skills Test 3 & 4 Skills Test 12Document3 pagesSkills Test 3 & 4 Skills Test 12Candelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- MythsDocument7 pagesMythsCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Parents and Schools Need Mutual Obligations and CommitmentsDocument4 pagesParents and Schools Need Mutual Obligations and CommitmentsCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- 24HoursForTheLord PDFDocument67 pages24HoursForTheLord PDFtraperchaperPas encore d'évaluation

- Parents and Schools Need Mutual Obligations and CommitmentsDocument4 pagesParents and Schools Need Mutual Obligations and CommitmentsCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Wars, Murders To Rise Due To Global Warming?: Shifts in Temperature and Rainfall Linked To More Aggression, Study SaysDocument5 pagesWars, Murders To Rise Due To Global Warming?: Shifts in Temperature and Rainfall Linked To More Aggression, Study SaysCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Resource Sustainable DevelopmentDocument24 pagesResource Sustainable DevelopmentCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- TIC IndagaciónDocument14 pagesTIC IndagaciónCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Emerging ThemesDocument19 pagesEmerging ThemesCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Think 2 Unit 4 Sample UnitDocument10 pagesThink 2 Unit 4 Sample UnitCandelaria Luque100% (1)

- Proyecto de EscrituraDocument2 pagesProyecto de EscrituraCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Placement Test 1 2016 KeyDocument4 pagesPlacement Test 1 2016 KeyCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Intelligence LightDocument4 pagesIntelligence Lightapi-3786405Pas encore d'évaluation

- Socratic Seminar Recommended Texts ListDocument3 pagesSocratic Seminar Recommended Texts ListCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Elements of The Socratic Method - I - Systematic QuestioningDocument8 pagesElements of The Socratic Method - I - Systematic Questioningdrleonunes100% (4)

- Placement Test 1 2016Document4 pagesPlacement Test 1 2016Candelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Narrative Essay National Geographic PDFDocument26 pagesNarrative Essay National Geographic PDFkimberleysalgado100% (1)

- Writing Test Placement TestDocument1 pageWriting Test Placement TestCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Think Students Book Starter Unit 9 PDFDocument8 pagesThink Students Book Starter Unit 9 PDFCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Think Students Book Starter Unit 9 PDFDocument8 pagesThink Students Book Starter Unit 9 PDFCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Gradable and Non-Gradable AdjectivesDocument23 pagesGradable and Non-Gradable AdjectivesCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 9 ThinkDocument8 pagesUnit 9 ThinkCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- Think Students Book Level 3 Unit 7Document8 pagesThink Students Book Level 3 Unit 7Jerry TurnerPas encore d'évaluation

- Passive VoiceDocument17 pagesPassive VoiceCandelaria LuquePas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Comprehensible Input Versus Comprehensible Output (Krashen Vs Swain)Document7 pagesComprehensible Input Versus Comprehensible Output (Krashen Vs Swain)Romina Paola PiñeyroPas encore d'évaluation

- Swain vs. Krashen Second Language AcquisitionDocument8 pagesSwain vs. Krashen Second Language AcquisitionBlossomsky9650% (2)

- The Role of Input and Output in Second LDocument14 pagesThe Role of Input and Output in Second LAndrea BolañosPas encore d'évaluation

- I+1 Teaching Techniques PDFDocument3 pagesI+1 Teaching Techniques PDFTomas MongePas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Output & Feedback in Second Language Acquisition: A Classroom-Based Study of Grammar Acquisition by Adult English Language LearnersDocument21 pagesThe Role of Output & Feedback in Second Language Acquisition: A Classroom-Based Study of Grammar Acquisition by Adult English Language LearnersLê Anh KhoaPas encore d'évaluation

- Report On Second Language Acquisition HypothesisDocument10 pagesReport On Second Language Acquisition HypothesisKin Barkly100% (1)

- Izumi & Bigelow (2000) Does Output Promote Noticing and Second Language Acquisition PDFDocument41 pagesIzumi & Bigelow (2000) Does Output Promote Noticing and Second Language Acquisition PDFAnneleen MalesevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied Linguistics S5 SummaryDocument49 pagesApplied Linguistics S5 SummaryDRISS BAOUCHE100% (2)

- The Role of Feedback in SlaDocument12 pagesThe Role of Feedback in Slaapi-360025326Pas encore d'évaluation

- Input and Output in The SLA ProcessDocument14 pagesInput and Output in The SLA ProcessSra. Y. DávilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Anxiety and L2 Written Production in The Language ClassroomDocument13 pagesAnxiety and L2 Written Production in The Language Classroomkarensun21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Output HypothesisDocument22 pagesOutput HypothesiszazamaoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Pleasure Hypothesis 3Document24 pagesThe Pleasure Hypothesis 3vinoelnino10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Second Language Acquisition Swain's Output Vs Krashen's InputDocument6 pagesSecond Language Acquisition Swain's Output Vs Krashen's Inputfrankramirez9663381Pas encore d'évaluation

- BLB - New Book 5Document95 pagesBLB - New Book 5drmohaddes hossainPas encore d'évaluation

- Krashen (1998) Comprehensible Output PDFDocument8 pagesKrashen (1998) Comprehensible Output PDFAnneleen MalesevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Lesson Plan 1Document10 pagesSample Lesson Plan 1api-335698310Pas encore d'évaluation

- SLA AssignmentDocument11 pagesSLA AssignmentMary Bortagaray67% (9)

- Assignment AnswersDocument9 pagesAssignment AnswersLeonardo MonteiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Alcc Eng AssignmentDocument10 pagesAlcc Eng AssignmentOlaaVegMelPas encore d'évaluation

- 11russell MoranoDocument26 pages11russell MoranoNicolas Matias Muñoz MoragaPas encore d'évaluation

- Error Correction 2Document24 pagesError Correction 2BAGASKARAPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensible Input in ESLDocument21 pagesComprehensible Input in ESLlacraneacsuPas encore d'évaluation

- Down - With - Forced - Speech - PDF Unit5Document7 pagesDown - With - Forced - Speech - PDF Unit5SilviaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Input in Second Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesThe Role of Input in Second Language AcquisitionJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICS100% (1)

- Principles of Language Learning and Teaching (Longman) - Chapter 10: Theories of Second Language AcquisitionDocument15 pagesPrinciples of Language Learning and Teaching (Longman) - Chapter 10: Theories of Second Language AcquisitionLuis Rodriguez Zalazar100% (1)

- Sample Lesson Plan 3Document10 pagesSample Lesson Plan 3api-335698310Pas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of Language Input in Language Learning: Taher BahraniDocument4 pagesImportance of Language Input in Language Learning: Taher BahraniAniaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Input in Second Language Acquisition PDFDocument6 pagesThe Role of Input in Second Language Acquisition PDFMARIA DEL CARMEN ALVARADO ACEVEDOPas encore d'évaluation