Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Did Bollywood Write India's Growth Script?

Transféré par

nimish-adhia-6248Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Did Bollywood Write India's Growth Script?

Transféré par

nimish-adhia-6248Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

20

Did Bollywood write Indias growth script?

Deewar

Feature

September 13, 2013 www.easterneye.eu Like us on www.facebook.com/easterneye

Follow us on www.twitter.com/easterneye www.easterneye.eu September 13, 2013

Feature

21

films depict changing attitudes to wealth

by Dr Raj Persaud

Hum Hain Rahi Pyaar Ke

Maine Pyaar Kiya; and (right) Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak

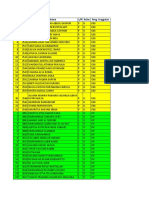

Exactly why did Indias economic miracle occur? Could the answer lie in hit Bollywood films? An academic from the US has recently published a study which statistically analysed the most popular lms in India each year since 1955, and found that characters of rich merchants have changed dramatically, from being portrayed as villains to now being heroes. Nimish Adhia from Manhattanville College, New York, argues that the shift in who were villains and heroes in popular cinema is linked to a profound change in Indian society. It was this fundamental transformation in attitude to commerce, in the decade before liberalisation of the Indian economy, which might explain India becoming the economic powerhouse it is today. Adhia contends that previously there was a deep Indian antipathy toward trade, with deep roots in the caste system. Religious scholars (brahmans) were at the top of the caste hierarchy, followed by soldiers (the kshatriyas), merchants (the baniyas) and peasants (the shudras). He contends that Bollywood mirrors the psyche of Indians. The Indian lm industry is the worlds most prolic, producing more than 1,000 lms year with a daily global viewership of over 12 million, second only to that of Hollywood. The lms chosen for this study entitled The role of ideological change in Indias economic liberalization, are all winners of the Filmfare Best Film award, given to one Hindi lm every year. These awards have similar prestige and popularity in Hindi cinema as the Oscars do in Hollywood. The Best Film is chosen through viewer polls and a panel of experts, so reect a mixture of elite and popular approval. A total of 52 lms, one for each year from 1954 to 2007 (there were no awards in 1987 and 1988) were analysed in the study published in the The Journal of Socio-Economics. Adhia argues that the dilemma of duty is recurrent in early Indian lms. In the climax of Mother India (1957), a mother takes a stand on her wayward son. In Deewar (1975), a police ofcer nds he must cuff his beloved older brother. In Upkaar (1967), two brothers debate tilling their family farm or moving for better opportunities. How these dilemmas are resolved, says Adhia, offers an insight into the prevalent values of the times. From the 1950s to the 1980s, he argues, the plot conundrums in Indian cinema invariably resolve in favour of duty. The mother in Mother India shoots and kills her son as he attempts to kidnap a woman an action that would have been shameful for the village. I am the mother of the entire village, she says as she picks up the gun. She is shown to lament his death for the rest of her life, but the lm idealises her as Mother India. But then, starting with Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985), a spate of lms arrived that celebrate the assertion of ones desire. This usually takes the form of falling in love. The young lovers in the big hit Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988) elope and endure enormous hardships because of their families opposition. Similarly in Ram Teri Ganga Maili, Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Hum Hain Rahi Pyaar Ke (1993), opposition to the romance arises from narrow concerns of class, status and language. But in the end, the lovers prevail. In India of the 1980s, the pursuit of individual wants, needs and desires was gaining legitimacy. In Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikander (1992), Sanju (Aamir Khan) who is initially the black sheep of his family gains respect by winning a cycling competition. The race, argues Adhia, embodies individual effort, competition, and self-discipline. While characters of earlier lms had attained heroism through sacrice to the in-

terests of family, village or nation, now the path to heroism lies in individual achievement. Around the same time, the Best Film award winning lms begin to show businessmen as extraordinarily moral. For example, Ashok Mehra (Raj Babbar) in Ghayal (1990), who is the older brother of the lms hero, dies while trying to protect his business from being used as a cover for anti-social activities. Maine Pyaar Kiya and Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994) both revolve around families headed by benevolent, self-made industrialist patriarchs. In contrast to the rich of the films from the 1950s, who were unfailingly wicked, the wealthy are now solicitous and magnanimous. In the plots of the lms from the 1980s and 1990s, problems do not arise from actions related to the pursuit of wealth, but factors such as untimely deaths and envious outsiders. Wealth has become unproblematic. To measure the portrayal of the rich businessmen systematically, Adhia analyses all male characters integral to the storylines of the lms. Female characters are excluded because they are rarely shown to pursue a vocation, let alone run a business. The analysis found the number of heroes as businessmen in popular Indian cinema has increased dramatically recently. The percentage of businessmen characters that are portrayed positively has increased, with an upsurge in the number of lms toward the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s in which the occupation of the hero is that of a trader or business owner. In the 1960s, not a single winner of the Filmfare Best Film award portrayed a hero who was a businessman, but by the 1990s, there were 11 heroes who were businessmen and only three who werent, meaning almost 80 per cent of heroes by the 1990s were businessmen. Also in the 1990s, there were 25 portrayals of businessmen in a positive manner and only four portrayals were negative, while in the 1970s there were twice as many negative portrayals of businessmen, in these films analysed, as there were positive depictions. Adhia argues that the economy boomed after these significant changes in Indian cinema. He believes films reflect the cultural changes that were occurring in society, which anticipate the coming economic revolution. But some will look at Adhias data and come to a different conclusion. Did Indian cinema kickstart the shift or just reflect it? And is it even possible that the script for the Indian economy was written by Bollywood?

Mother India; and (below left) Hum Aapke Hain Kaun

We Interiors in London specialise in all areas of interiors soft furnishings We are Manufactures of Bespoke Made to Measure Soft Furnishings our services include Curtains Blinds - Roller,Roman,Venetian, & Vertical Shutters Leather & Painted Curtain Tracks - Electric & Manual Silent Gliss & Lutron Curtain Poles Cushions & Covers Headboards Upholstery & Re- Upholstery Bespoke Sofas Furniture & Mattresses Wide Collection of Fabrics Wallpapers Bespoke Cornices Professional Fitting Service Residential & Commercial

Free Measuring Service Free Consultation Free Estimates

With over 35 years in the interior soft furnishing industry the quality of our workmanship is renowned, we pride ourselves in our ability to interpret our clients requirements to the highest of standards, We can produce outstanding curtains and blinds and all accessories to any specification working with all types of material.

Tel : 0208 459 2436 M. : 07 888 692 890

E-mail : info@interiorsinlondon.co.uk Web : www.interiorsinlondon.co.uk

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- CHAPTER 4 SUMMARY - Living JusticeDocument3 pagesCHAPTER 4 SUMMARY - Living Justicecorky0183% (6)

- Kumpulan Lirik HadrohDocument18 pagesKumpulan Lirik HadrohGita Raya95% (22)

- Issue 3 - As Surely As The Sun LiteraryDocument51 pagesIssue 3 - As Surely As The Sun Literaryapi-671371562100% (1)

- Sarang Kulkarni - FMM2021032Document3 pagesSarang Kulkarni - FMM2021032Sarang KulkarniPas encore d'évaluation

- Film StudiesDocument32 pagesFilm StudiesArchanaa GnanaprakasamPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Proposal FinalDocument9 pagesResearch Proposal FinalRaja ShahPas encore d'évaluation

- Changing Trends in World CinemaDocument22 pagesChanging Trends in World CinemaPiyush ChaudhariPas encore d'évaluation

- Film As A Medium of Mass CommunicationDocument4 pagesFilm As A Medium of Mass CommunicationnamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Stereotypical Portrayal of Women in Hindi CinemaDocument9 pagesStereotypical Portrayal of Women in Hindi CinemaShalini SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- History of BollywoodDocument16 pagesHistory of BollywoodZaidPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effect of Toxic Masculinity in IndiaDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Toxic Masculinity in IndiaSanchita PaulPas encore d'évaluation

- Bollywood Films (Emergence)Document3 pagesBollywood Films (Emergence)Nadia ZehraPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature To Films: Indian ContextDocument5 pagesLiterature To Films: Indian ContextAmanroy100% (1)

- Research Paper On Indian MoviesDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Indian MoviesthrbvkvkgPas encore d'évaluation

- Change in Trend of Indian CinemaDocument4 pagesChange in Trend of Indian CinemaSanjana OjhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lagaan N AfterDocument18 pagesLagaan N Afterletterstomukesh100% (1)

- Nishanth R. Research ProposalDocument11 pagesNishanth R. Research ProposalADNAN KHURRAMPas encore d'évaluation

- Female Body and Male Heroism in South Indian Cinema: A Special Reference To Telugu CinemaDocument12 pagesFemale Body and Male Heroism in South Indian Cinema: A Special Reference To Telugu CinemafadillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Representation of Women'S Identity in Bollywood: Chapter - IvDocument50 pagesRepresentation of Women'S Identity in Bollywood: Chapter - IvnutbihariPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Must See Movies For MBADocument3 pages10 Must See Movies For MBAVignesh PillaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Methodology PVR Vs CineMaxDocument47 pagesResearch Methodology PVR Vs CineMaxSiddharth Vachhiyat100% (1)

- Filmy ChakkarDocument63 pagesFilmy Chakkarmanish prasad singhPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- VikramDocument8 pagesVikramdasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film IndustryDocument8 pagesFilm Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film Industrydasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- VANSHITA SINGH - Movie Review Admn LawDocument2 pagesVANSHITA SINGH - Movie Review Admn LawshantanuPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Portrayal of Women in The Popular Indian Cinema PDFDocument18 pagesPortrayal of Women in The Popular Indian Cinema PDFHabiba Khan100% (1)

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film IndustryDocument8 pagesFilm Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film Industrydasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film IndustryDocument8 pagesFilm Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film Industrydasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- History of Commercial ArtDocument5 pagesHistory of Commercial ArtMudassir AyubPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- P.barathiraja Tamil DirectorDocument8 pagesP.barathiraja Tamil Directordasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiJecci AlbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film IndustryDocument8 pagesFilm Career: Tamil Filmmaker Tamil Film Industrydasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Report Version 16Document111 pagesReport Version 16Harsh VardhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiDocument8 pagesFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Cinema What It Can Teach Us?: Management Consultant, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, IndiaDocument2 pagesIndian Cinema What It Can Teach Us?: Management Consultant, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, IndiaJayakrishnan BhargavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hare, R M - Sorting Out EthicsDocument103 pagesHare, R M - Sorting Out EthicsJunior100% (1)

- Devotional Paths To Divine (Autosaved)Document22 pagesDevotional Paths To Divine (Autosaved)divyaksh mauryaPas encore d'évaluation

- Master Maria MichalowskaDocument150 pagesMaster Maria MichalowskaKevin Pee RomeraPas encore d'évaluation

- Seclusion and Veiling of Women PDFDocument24 pagesSeclusion and Veiling of Women PDFJohnPaulBenedictAvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied-Sexual Discourse, Erotica in Today's Arabic Literature-Nadia Ghounane - 2Document12 pagesApplied-Sexual Discourse, Erotica in Today's Arabic Literature-Nadia Ghounane - 2Impact JournalsPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Grade World History: Chapter 4 Notes - The Rise of Muslim StatesDocument19 pages7 Grade World History: Chapter 4 Notes - The Rise of Muslim StatesNirpal MissanPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3 Module 10Document4 pagesChapter 3 Module 10Wild RiftPas encore d'évaluation

- Prog2 02Document61 pagesProg2 02klenPas encore d'évaluation

- BOOK REVIEW On Akhuwat Ka Safar by DR - Mohammad Amjad SaqibDocument3 pagesBOOK REVIEW On Akhuwat Ka Safar by DR - Mohammad Amjad SaqibMERITEHREER786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pratyabhijnahridayam - The Secret of Recognition. Kshemaraja Tr. J.singh (Delhi, 1980)Document192 pagesPratyabhijnahridayam - The Secret of Recognition. Kshemaraja Tr. J.singh (Delhi, 1980)chetanpandey100% (3)

- Debate Worksheet - Religion ProDocument5 pagesDebate Worksheet - Religion Proapi-343814983Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final PaperDocument3 pagesFinal Paperapi-549606779Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ferraris and His WORKDocument8 pagesFerraris and His WORKeric parlPas encore d'évaluation

- Dato Lee Chong WeiDocument7 pagesDato Lee Chong WeiNurfarah Ain0% (1)

- Christ Our High Priest Bearing Our IniquityDocument18 pagesChrist Our High Priest Bearing Our IniquityJohann MaksPas encore d'évaluation

- Application Form JH20 UGJ 1767Document1 pageApplication Form JH20 UGJ 1767raj sahilPas encore d'évaluation

- How Beautiful Is The Morning: Birthday SongsDocument4 pagesHow Beautiful Is The Morning: Birthday SongsfendyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bakunawa InfoDocument2 pagesBakunawa InfoRenbel Santos GordolanPas encore d'évaluation

- A Leader's ValuesDocument20 pagesA Leader's ValuesAndroids17Pas encore d'évaluation

- Greek & Roman Mythology (Gods & Goddesses)Document2 pagesGreek & Roman Mythology (Gods & Goddesses)Christopher MacabantingPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 5 Main Course BookDocument38 pagesUnit 5 Main Course BookSUDHASONI100% (1)

- Excerpts-Thou Shalt Not Bear False WitnessDocument9 pagesExcerpts-Thou Shalt Not Bear False Witnesselirien100% (1)

- Tes Praktek Ibadah RegulerDocument49 pagesTes Praktek Ibadah RegulerTU MTsN Tambakberas JombangPas encore d'évaluation

- Censorship in Saudi ArabiaDocument97 pagesCensorship in Saudi ArabiainciloshPas encore d'évaluation

- Christ Our Righteousness - Romans 1:16-32 John 3:16-18, Romans 10:6-10Document2 pagesChrist Our Righteousness - Romans 1:16-32 John 3:16-18, Romans 10:6-10JimPas encore d'évaluation

- Puranic Stories RevisedDocument171 pagesPuranic Stories RevisedAnonymous 4yXWpDPas encore d'évaluation

- Skeptic 281Document67 pagesSkeptic 281spinoza456Pas encore d'évaluation