Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hualde-Schwegler Palenquero

Transféré par

all1allTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hualde-Schwegler Palenquero

Transféré par

all1allDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Published in Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 23.

1 (2008): 1-31

INTONATION IN PALENQUERO

Jos Ignacio Hualde University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Armin Schwegler University of California, Irvine

The least understood aspect of Palenquero phonology is its intonational system. This is a serious gap, as it is precisely in the realm of prosody that the most striking phonological differences between Palenquero and (Caribbean) Spanish are apparent. Although several authors have speculated that African influence may be at the source of Palenqueros peculiar intonation, to date published research offers no detailed information about the intonation of the creole. The goal of this study is to remedy this situation. Here we identify several specific intonational features where conservative (or older-generation) Palenquero differs from (Caribbean) Spanish. One of these features is a strong tendency to use invariant word-level contours, with a H tone on the stressed syllable and L tones on unstressed syllables, in all sentential contexts, including prenuclear positions. A second feature that we have identified is the use of a sustained phrase-final high or mid level contour in declaratives accented on the final syllable, and a long fall in declaratives accented on the penult. The final section addresses the issue of the possible origin of these intonational features. We point out similarities with Equatorial Guinea Spanish and conclude that, at some point in the history of Palenquero, the Spanish prosodic system was interpreted as involving lexical tone, in conformity with claims in the literature regarding several Atlantic creoles. KEYWORDS: creole, Colombia, intonation, Palenque, Palenquero, prosody, Spanish, substrate, tone, accent, vowel lengthening, Bantu

Palenquero intonation

1. Introduction Palenquero is a creole language spoken in El Palenque de San Basilio, Colombia, located about 60 km inland from the city of Cartagena de Indias. Founded in the second half of the 17th century, this former maroon community has been speaking creole and Spanish for several centuries (Schwegler, 1998: 223-237). The fact that the inhabitants of Palenque spoke both Spanish and their own language already early on is noted in a document of 1772 (Patio, 1983:183). Palenquero was first identified as a creole in publications by Granda (1968) and Bickerton & Escalante (1970). Over the last 30 years or so, the almost exclusively Black community has been shifting towards increased use of Spanish (Schwegler & Morton, 2003). Although Patio (1983) describes the situation he encountered in the late 1970s as one of general bilingualism, he notes that older speakers tend to use the creole more, a situation which still obtains today. Recently, Schwegler (in press b) has observed that many younger people in Palenque have only a passive command of the creole. Conversations in Palenquero are characterized by almost constant extra- as well as intra-sentential switches between creole and Spanish (Patio, 1983: 186, Schwegler & Green, in press). Despite this heavy interaction (or even overlapping) of the two local languages, at the descriptive level, Palenquero can readily be characterized as a separate code from Spanish. At the same time, speakers are very much aware of the existence of two distinct languages in their community. Palenquero displays many of the syntactic features associated with Atlantic creoles (Bickerton & Escalante, 1970; Granda, 1968, 1978; Patio, 1983, 2002; Schwegler & Green, in press). Its lexicon is derived almost exclusively from Spanish, but it contains some two hundred elements of Bantu origin (specifically Kikongo, according to Schwegler, 2002a, 2002b, in press a). Of these, only a dozen or so are used in daily speech [fn1]. Common Palenquero words of Bantu origin are: mon child (< Kik. mwana child), Kik. lumbal name of a local funeral tradition (<Kik. lu-mblu memory, recollection, melancholy), and ma ngmbe cattle < Kik. ngombe cattle) (see Schwegler, 2002a) The last example contains the particle ma (see Moino, 2005), from the Bantu class 6 prefix, in the standard classification of Bantu noun classes (see, e.g., Wald, 1987: 1000, Katamba, 2003: 104), which has become a general plural marker in Palenquero; e.g.: ma hnde people (< Sp. gente), ma mbe men (< Sp. hombre), ma plo trees (< Sp. palo). [fn 2] Moino (2002) and Schwegler (2002b) also discuss possible cases of African influence on Palenquero (morpho)syntax. In addition to these

Palenquero intonation

lexical and grammatical Africanisms, one finds in Palenque a series of cultural patterns that are similarly suggestive of Bantu influence (Schwegler,1992, in press a). The present-day segmental phonology of Palenquero does not differ much from that of the neighboring Caribbean Spanish varieties. [fn 3] Significantly, there are no differences in segmental inventory (Bickerton & Escalante, 1970; Patio, 1983: 90; Schwegler, 1998: 264-267). Coda /s/ variably [s], [h] and [] in Caribbean Spanish has been systematically eliminated: ut < Sp. usted you (sing./formal), peko < Sp. pescado fish. That is, Palenquero has taken the weakening of coda /s/, present in Caribbean and many other Spanish varieties, to its logical conclusion. Sequences of liquid plus stop have given rise to geminates: mtte < Sp. martes Tuesday, kabbn < Sp. carbn (char-)coal, Tubbko < Sp. Turbaco (toponym), a process variably found in Cartagena (Becerra, 1985; Nieves Oviedo, 2002) as well as some areas of Cuba (Guitart, 1976) and the Dominican Republic. In Palenquero, as in these Caribbean varieties of Spanish, voiceless geminates may be simplified, but voiced geminate stops contrast with voiced approximants or fricatives (cf. lgo [lo] lake vs. lggo [lg:o] long < Sp. largo). Intervocalic /d/ often becomes a flap []: kuiro care(ful) < Sp. cuidado, as is also the case in some rural coastal Colombian varieties (Granda, 1994) and the Dominican Spanish dialect of El Cibao (Nez Cedeo, 1987). Nevertheless, in spite of these coincidences with Caribbean Spanish, Palenquero also exhibits clear indications of an earlier, more Bantu-like phonological stage. Two contemporary features in particular are indicative of an earlier reinterpretation of the Spanish allophonic alternation between initial [b-, d-, g-] and intervocalic [--, --, --] as the typical Bantu pattern with initial [mb-, nd-, g-] and intervocalic [--, -l-, --] (see, for instance, Maddieson, 2003: 24). These features are: (1) the optional and still very common prenasalization of word-initial plosives like nd < Sp. dar to give, ngat < Sp. gastar to spend, mbsa < Sp. bolsa bag, pocket ; and (2) the replacement of intervocalic /d/ with /l/, kel < Sp. quedar to stay, bitlo < Sp. vestido dress. Also somewhat suggestive of Bantu substratal influence (although the process is also found in other languages) is the voicing of postnasal voiceless stops obligatory in a select few words like timbo < Sp. tiempo time, kumbl < Sp. comprar to buy, plnda < Sp. pltano banana, sind < Sp. sentir to feel, and Palnge < Palenque, but free in items like kand ~ kant to sing < Sp. cantar (for this voicing process in Bantu, see Hyman, 2003: 50). [fn 4] Another Bantu-like feature is the replacement of rhotics with /l/, observable in a number of words: al < Sp. arroz rice, plo < Sp. perro dog, sel < cerrar close,

Palenquero intonation

shut, kolasn < Sp. corazn heart (Patio, 1983: 96-98, Schwegler & Morton, 2003: 135, item 7; see also 138, item 14). Against this background, it would not be surprising if Palenquero prosody also preserved vestiges of a Bantu substrate (Patio 1983: 109-110). In fact, in the first description of Palenquero, Montes (1962: 450 [cited in Patio 1983: 110]) refers to the peculiarsimo tonillo palenquero, una de cuyas ms salientes caractersticas es la notoria elevacin del tono y el alargamiento cuantitativo de la slaba acentuada [fn 5], for which he surmises an African origin. Bickerton & Escalante claim that in Palenquero, finalsyllable accent is a matter of high tone rather than stress, and that there are some pairs, such as kusina kitchen, kusin to cook, which are only tonally distinguished (1970: 257). While acknowledging the existence of striking intonational patterns, Patio (1983: 109-110) denies the existence of contrastive lexical tone in Palenquero, preferring to interpret word-level prosody in terms of stress (see also Patio, 2002: 28). All scholars who have subsequently researched Palenquero seem to agree, explicitly or implicitly, that the creole lacks lexical tonal contrasts. The fact remains, however, that very little is known about Palenquero intonation (but see Moino 2003: 524-525 for a brief description). Prosody continues to be the least understood aspect of Palenquero phonology, even though it is precisely at this level that one finds the most remarkable synchronic phonological differences with respect to the neighboring Spanish varieties. As Megenney states:

La faceta que sin duda es la ms difcil de resolver es la de los patrones de entonacin del palenquero, que en algunas instancias, difieren del espaol costeo normal, y eso, en donde se esperara, en los tonemas. La pregunta inmediata que nos hacemos al escuchar estas diferencias de entonacin se relaciona con el posible vnculo que los patrones anmalos del palenquero tengan o no con los sistemas tonales de las lenguas africanas. Hasta ahora este problema es irresoluble. (1986: 22) [fn 6]

A goal of this paper is to shed some light on this hitherto unsolvable problem of the origins of Palenquero intonation. The issue that we want to address is what makes Palenquero intonation so different from Spanish, including Caribbean and Colombian Spanish, as several researchers have reported. That is, our goal is to try to identify specific aspects of Palenquero prosody that may account for its distinct intonational impression. Once some of these features are identified, we will proceed to examine whether the Bantu substrate may have been a causal factor. In section 2 we describe our data sources (recordings of Palenquero). Section 3 offers a brief overview of Spanish intonation, focusing on the major features that will be

Palenquero intonation

useful in the comparison. In section 4 we examine specific aspects of Palenquero declarative patterns that seemingly differ from Spanish. Section 5 concentrates on interrogative intonation. The main intonational differences between Palenquero and Spanish are summarized in Section 6, where we also review the possible influence of a Bantu substrate, and compare Palenquero intonation with that of other Atlantic creoles.

2. Corpus for the study of Palenquero intonation For the purpose of this study, we have used two recordings of Palenquero speech. Our main source of examples is a recording made by one of the authors, A. Schwegler, in Palenque in the summer of 1988. The recording contains a lively, highly informal and relaxed dialogue between two female speakers, R. (born 1919) and V. (born 1914). The conversation is interspersed with occasional remarks by the researcher and other participants. As expected, code-switches between Palenquero and Spanish are frequent. [fn 7] Our secondary recording, also obtained in situ in 1988, is a long monologue by a younger but very competent speaker of Palenquero, S. (born 1955).The monologue is solely in creole. The recordings were digitized and analyzed with PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, 1999-2005). Heavily stigmatized (see Patio, 1983: 110), [fn 8], the traditional tonillo (singsong intonation) of traditional Palenquero speech has been avoided by the latest generations to the point where contemporary local intonational patterns show a much higher degree of convergence with those of regional Spanish. In light of Palenques sociolinguistic history and prevailing local language attitudes (Schwegler, 1998; Schwegler & Morton, 2003), it is logical to assume that the age of informants and the date of a recording significantly condition the prosodic features we seek to examine in this study. Older speakers and early recordings are thus more likely to reveal the special intonational contours that Montes (1962) and others have noted. These and other considerations have guided us in selecting the aforementioned early recording from the late 1980s as our principal data source. The general auditory impression obtained from our recordings confirms the (often vague) descriptions made in the above-mentioned earlier investigations. Frequently, the intonational patterns of Palenquero differ markedly from those found in any monolingual Spanish variety. In this paper, our emphasis will be on patterns that appear to significantly differ from those of Spanish.

Palenquero intonation

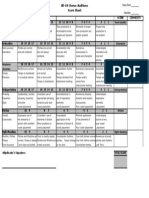

3. Basic features of Spanish stress and intonation Spanish has contrastive lexical stress on one of the last three syllables of the word; e.g. nmero number, numero I number, numer s/he numbered (stressed syllables are underlined). Function words and expressions may be either lexically stressed or unstressed (Navarro Toms, 1977: 187-194; Quilis, 1993: 390-395; Hualde, 2005: 233-235). definite articles and prenominal possessives, for instance, are unstressed (el libro the book, nuestros amigos our friends), whereas indefinite articles and demonstratives are stressed (un libro a book, estos amigos these friends). As in English and many other intonational languages, intonational contours in Spanish can be analyzed as resulting from the interpolation between tonal events associated with stressed syllables (known as pitch accents) and tonal movements at the end of phrases (boundary tones) (Pierrehumbert, 1980; Beckman & Pierrehumbert, 1986; Ladd, 1996; Gussenhoven, 2004). Figure 1 illustrates a typical neutral declarative contour in Spanish with the text le dieron el nmero de vuelo they gave him the number of the flight. [fn 9] The figure contains three time-aligned tiers: the text of the utterance, divided into syllables, the waveform, and the intonational curve. This intonational curve shows three pitch excursions, corresponding to the three lexically stressed syllables in the utterance. Notice, however, that the first two tonal peaks occur after the stressed syllable. The three pitch accents in the figure have a rising configuration: the pitch rises through the stressed syllable from a low point or valley at the beginning of each of the three lexically stressed syllables (die-, n- and vue-). The peak is reached in the following syllable (-ron, -me-) in the case of the first two (prenuclear) accents, and within the stressed syllable in the last or nuclear accent [fn 10]. At the end of a final declarative, there is normally a low boundary (indicated with the symbol L% in the tonal transcription), resulting in a final fall, as can be seen in Figure 1. The same Figure 1 also shows that in final declaratives, accentual peaks are typically lower from the beginning to the end of the intonational phrase (Prieto et al., 1995). This phenomenon, known as declination or downtrend, is typical of final declaratives. Exceptions to declination are, nevertheless, found in spontaneous speech (Face, 2003).

Palenquero intonation

Fig. 1.

Example of neutral declarative in Spanish: le to him dieron el gave (3. pl.) the LH nmero de vuelo number of flight LH LH-L%

they gave him the number of the flight = they gave him the flight number Lexically stressed syllables are underlined. Notice that this example contains three rising pitch-accents (LH). The beginning of the rise (a valley) coincides with the onset of the lexically stressed syllable. The peak is displaced to the posttonic in the two prenuclear accents. All three peaks are progressively reduced (declination). The utterance ends with a boundary low tone (L%). In Spanish neutral declarative sentences, the pitch thus typically rises during the stressed syllable of (most) content words, and reaches a peak in the posttonic syllable, except in the final or nuclear accent, where the peak occurs within the stressed syllable (e.g. Prieto et al., 1996; Sosa 1999; Hualde, 2002, 2003). It is not the case, however, that lexical stress is always manifested as a pitch rise. Spanish does not have lexical tone.

Palenquero intonation

Instead of rises, other pitch-accents can be chosen to convey different pragmatic meanings. For instance, in yes-no questions, the last stressed syllable is often associated with a low tone, before a final rise that is confined to the posttonic syllable(s) (see Fig. 2. In the figures, the total duration of the utterance is given in seconds, abbreviated (s)).

300

le 0 0

die

ron

el

nu' me ro

de

vue

lo 1.29655

Time (s)

Fig. 2.

Example of yes/no question in Spanish:

(Note that the last stressed syllable, vue-, is associated with a L tone.)

Le dieron el to him gave (3 pl.) the LH

nmero de number of H

vuelo? flight L-H%

Did they give him the flight number?

Palenquero intonation

Also, in many dialects, neutral declarative nuclear accents are realized as a fall during the stressed syllable, as in the Coastal Colombian Spanish contour in Figure 8 (p. 000). That is, as in other languages without lexical tone, stressed syllables are not systematically characterized by any particular pitch contour. Lexically stressed syllables function as anchors for intonational pitch accents, but the shape of pitch accent varies depending on pragmatics factors. A lexically stressed syllable may be associated with a rising contour (LH), a high tone (H), a falling contour (HL), a low tone (L), or no tonal target at all. How such a lexically stressed syllable is ultimately realized depends on the type of sentence, the position of the word in the sentence, the distribution of old and new information, and so on. Certain pitch accents are more common than others, but there are several possible contours that may be associated with the stressed syllable of the word. The specific inventory depends on the language (for Spanish, see Beckman et al., 2002; Hualde, 2003, among others). For the purpose of this paper, it is important to note that in Spanish, just like in English and other stress languages, words cited in isolation have a rise that is confined to the stressed syllable, with a fall on the posttonic. This is the contour on the word vuelo flight in Figure 1, which is in nuclear position in a declarative sentence. Even though this may not be a particularly frequent contour in discourse (a rise with displacement of the peak to the posttonic may be more common), the nuclear or citation contour is especially important, as it has been observed that speakers of languages with lexical tone tend to adopt borrowings from stress-accent languages with the tonal pattern they receive in citation form (Devonish, 2002).

4. Declarative sentences in Palenquero 4.1. Pitch accents In the Palenquero corpus that we have examined, declarative sentences typically exhibit a high tone on every stressed syllable (that is, on every syllable that would be stressed in the Spanish cognate word), without any displacement of the peak. This pitch accent is thus contrary to the typical Spanish pattern of rising accents with peaks displaced to posttonic syllables. The stressed syllable is high for most of its duration, and there is a low tone on the posttonic. Successive peaks show very little or no declination. This is illustrated in the two representative examples given in Figures 3 and 4 (speakers

Palenquero intonation

10

are identified by their initial in parenthesis after the text). Notice that in Figure 3, depu i tn buk peko a Katahna [fn 11] later on I will go look for fish in Cartagena (Sp. despus voy a buscar pescado en Cartagena), every syllable that would have lexical stress in Spanish is associated with a high tone, and all the high-toned syllables have roughly the same F0 level, without any declination. [fn 12]

400

de 0 0

pu

tn

bu

pe

ko

ka

ta

na 2.32646

Time (s)

Fig. 3.

Palenquero: depu i later I H

tn FUT H

buk go get H

peko a Katahna (V.) fish in Cartagena H H

later I will go get fish in Cartagena The second example, i t yeb plnda I am taking along bananas in Figure 4 again illustrates the presence of a high tone on all stressed syllables. Readers will note that once again there is essentially no declination.

Palenquero intonation

11

500

i 0 0

ye

b Time (s)

pln

da 1.51994

Fig. 4.

Palenquero: i t yeb I T/A take H H

FOCUS

plnda. banana H

(V.)

I am taking along bananas.

Consider also the example in Figure 5: y s tn malo n pogke ri m mor I do not have a husband, because mine died (cf. Sp. yo (s que) no tengo marido porque el mo ha muerto). As shown, all syllables that in the Spanish cognate words would be stressed are once again realized with a H tone in Palenquero. Note in particular (1) the absence of tonal valleys between the three H-toned syllables with which the utterance

Palenquero intonation

12

starts, and (2) the lack of peak displacement. For instance the phrase-medial word malo husband (< Sp. marido) is realized with a L-H-L surface pattern. In Spanish discourse this pattern on the word marido would be expected only if the word were realized with special emphasis or in isolation.

Palenquero intonation

13

500

yo' si' te'n mai' lonu' po ke rimi a' mo ri' 0 0 Time (s)

Fig. 5. Palenquero: y s I AFFIRM H H ri of tn have H malo husband H mor (R.) die H n NEG H pogke because

2.5795

m mine has H H

I have no husband, because mine died.

Palenquero intonation

14

As a final example, consider the contour in y-a ten ma-numno m, y-a ten mahan m I have my brothers, I have my children (Fig. 6). In this example the postnominal possessive m my is emphasized and uttered with an upstepped H tone. Nevertheless, the preceding word is realized in both cases with the contour it would presumably receive in isolation: numno L-H-L, mahan L-L-H (that is, with the contour that Spanish words with penultimate and final stress, respectively, would receive if pronounced in isolation).

Palenquero intonation

15

500

y-ate ne'manu ma'nomi'y-a tene' mahana' mi': 0 0 Time (s)

Fig. 6. yI a

T/A

2.41163

Palenquero: ten have H ma-numno m, y- a ten PL brother mine I T/A have H HL% H mahan m.( R.) boys mine H HL%

I have my brothers, I have my children (= I have several brothers and children).

Palenquero intonation

16

The reinterpretation of stress as lexical association of a H tone with the stressed syllable has been claimed both for Caribbean creoles (Devonish, 1989, 2002) and for African varieties of European languages, such as Nigerian English (Amayo, 1980). This transfer of high tone onto the stressed syllable would have resulted from essentially the same process that occurs in borrowings from English and Portuguese in a number of Bantu and other West African languages: the intonational contour of words in isolation in the source language is taken to characterize the word at the lexical level (Carter, 1987; Devonish, 2002), That is, the pitch contour in the citation form of words is taken as an integral part in the pronunciation of the word in all contexts, allowing for very little flexibility in intonation. Conservative Palenquero intonation with its consistently high tone on stressed syllables and low tones on unstressed syllables would appear to be in agreement with this cross-linguistic pattern. Lack of peak displacement in prenuclear rising accents has been reported for two bilingual or contact Spanish varieties: the Spanish of Cuzco (ORourke, 2004) and the Spanish of bilingual Basque speakers (Elordieta, 2003). Buenos Aires Spanish also appears to differ from other Spanish dialects in this respect (Sosa, 1999: 187; Colantoni, 2005), apparently as a result of a recent change triggered by Spanish/Italian bilingualism at the beginning of the 20th century. We should note, however, that, impressionistically, Palenquero intonation differs substantially from these Spanish varieties. A strict alignment within the stressed syllable of accentual peaks cannot, therefore, be considered the crucial ingredient for the Palenquero tonillo. What appears to cause the distinct prosody of Palenquero is, at least in part, the level high tone over much of the duration of stressed syllables. This contour is better characterized as a level H tone rather than as a rising accent LH, as we typically find in Spanish.

4.2. (Absence of) boundary tones in phrases with oxytonic ending Another striking feature of Palenquero intonation is that final declaratives sometimes end in a level tone, without a final drop. In utterances where the last word is oxytonic (that is, has final stress, as in mam, in Fig. 7), we often find a level high tone on the last syllable, without the final fall that is nearly obligatory in Spanish (as it is in English) in final declarative sentences. The example i t sin mam I am without mother = I no longer have a mother (Fig. 7) and the corresponding Colombian Spanish yo estoy sin mam (Fig. 8) illustrate this intonational difference.

Palenquero intonation

17

500

y- 0 0

sin

ma

m 1.23526

Time (s)

Fig. 7. Palenquero: i I t T/A be sin mam. (V.) without mother

I am without mother = I no longer have a mother.

Palenquero intonation

18

500

yo 0 0

es

toy

sin

ma

ma 1.082

Time (s)

Fig. 8.

Coastal Colombian Spanish: yo estoy sin mam. I am without mother = I no longer have a mother. Note the intonational fall throughout the final, lexically stressed syllable. Analytically, the toneme (last pitch-accent and boundary tone) is HL* L%.

Bickerton & Escalantes (1970: 257) claim that final-syllable accent is a matter of high tone rather than stress would appear to refer to this striking intonational feature of Palenquero: the use of a level H tone on phrase-final accented syllables. It is interesting to note that in the example in Figure 7 where the two last syllables are

Palenquero intonation

19

segmentally identical (mam) and, therefore, directly comparable, there is no lengthening of the acccented syllable. Instead, the penultimate is slightly longer: /ma/ = 277 ms, /m/ = 267 ms. Bickerton & Escalante are, thus, right in their observation that final prominence in Palenquero may be cued by purely tonal means in some instances. We will return to this point in the next subsection. Another example of a level H on a phrase-final accented syllable, from S.s monologue, is given in Figure 9.

200

a... s to t 0 0

kumo

guan

dan

d 1.6761

Time (s)

Fig. 9. Palenquero: a sto t kumo guandand (S.) ah we T/A be like spider ah, we are like spiders [meaning: we are spreading / relocating to everywhere] Note the level H tone on the last syllable.

Palenquero intonation

20

4.3. Final downstep In sentences with the same basic structure as those examined in the preceding subsection, the H tone of the last syllable is sometimes downstepped, so that it is pronounced at the same level tone as the preceding toneless (pretonic) syllable. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figures 10 and 11. From the data available it is not yet entirely clear what pragmatic or other factors trigger this downstepping of utterance-final highs. The sentence in Figure 10, i- tn si mon I have six children was produced in answer to the question kunto mon b ten? how many children do you have?. Notice the fall after the H tone in si, and the level phonetic mid-tone over the last two syllables (again without a final boundary tone, like in Fig. 7 and 9). That is, underlying mon LH is realized as phonetic M-M in this example. As in Figure 7, the penultimate syllable is actually longer than the accented final syllable: mon /mo/ = 286 ms, /n/ = 209 ms.

Palenquero intonation

21

500

y- 0 0

tn

si

mo

n 1.23367

Time (s)

Fig. 10. Palenquero:

/- I T/A H H y- I T/A H

tn have H tn have H

si six H si six HL%

mon/ (V.) child H mon child M M

I have six children

Palenquero intonation

22

Exactly the same phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 11, where pa yeb pa bend to take along to sell [it] (durations: bend /ben/ = 255 ms, /d/ = 185 ms) exhibits a final level mid-tone over the last two syllables. This pattern is unlike anything normally found in Spanish, where, as noted above, final declaratives usually fall at the end of the utterance, even if the syllable is stressed. In other words, in Spanish (as in other European languages), the presence of a L% boundary tone at the end of a final declarative is essentially obligatory.

400

pa 0 0

ye

pa Time (s)

ben

d 1.2107

Fig. 11. Palenquero

/pa yeb to take H [L LH

pa to L

bend/ (V.) sell H M M]

to take along to sell [it]

Palenquero intonation

23

A similar phenomenon is illustrated in the second sentence in Figure 12. This figure contains two exclamative utterances: yeb m t! n deh m t n! take me along!, do not leave me [here]!. Both sentences end with a stressed monosyllabic word. As shown in the figure, the last H-toned syllable in each of the two sentences is downstepped to mid (represented as M in the transcriptions). The second of the two sentence ends with a level tone, like some of the other examples above. In contrast, the last syllable of the first sentence in Figure 12 shows a falling contour; that is, here we find a pronounced drop in pitch after the downstepped H tone on its final syllable. Unlike in the other examples studied here and in the preceding subsection, the final syllable is extraordinarily lengthened to over 500 milliseconds: yeb m t, /ye/ = 110 ms, /b/ = 171 ms, /m/ = 196 ms, /t/ = 568 ms. This is a (somewhat anomalous) example of a contour we will examine in section 4.4.

Palenquero intonation

24

500

yeba' mi' 0 0

te'

nu'deha'mi' te' Time (s)

nu' 2.43441

Fig. 12. Palenquero: /yeb m take me H H t. n deh m you (s.) NEG leave me ML% H H H t you H n/ (R.) NEG M

Take me along! Do not leave me [here]!

Palenquero intonation

25

In partial summary, it thus appears that a H tone linked to the last syllable of a phrase can be downstepped to M both after another H toned-syllable (Fig. 12), and after a toneless syllable (Figs. 10 and 11).

4.4. The long nuclear fall As we mentioned in section 1, Montes noted as a salient feature of Palenquero intonation the noticeable raising of the tone and the quantitative lengthening of the stressed syllable (1962: 450, our translation). Patio adds that, more exactly, this affects the last stressed/accented syllable in the sentence (la ltima slaba acentuada de la oracin [1983: 110]). We would further add that this nuclear contour tends to occur when the last word in the intonational phrase is paroxytonic (i.e., has penultimate accent), since, when the accent is on the last syllable, the contours described in the previous two subsections tend to occur instead (but most words are, in fact, paroxytonic). An example of this contour is illustrated in Figure 4, on the phrase-final paroxytonic word plnda. In our corpus, this contour, which we will dub the long nuclear fall, is particularly frequent in S.s monologue. The two main features of this contour were adequately captured in Montes impressionistic observation. One of them is the noticeable raising of the tone. Most often the final pitch accent reaches approximately the same level as a previous pitch accent peak, or rises even higher. This is tantamount to saying that, in this contour, there is little or no declination. The second feature is the extraordinary lengthening of the stressed syllable. If the syllable is open, the tone usually remains as a level H on the stressed syllable and falls on the posttonic. If the stressed syllable has a coda consonant, the fall is initiated during the coda of this syllable. Although the first sentence in Figure 12 above appears to show a long nuclear fall, this example is unusual in two respects. First, the contour occurs on a final accented syllable. Secondly, its peak is downstepped. We attribute these features to the exclamatory force of the utterance. In the corpora that we have examined, long nuclear falls are rare on oxytonic phrases, and the few examples in our corpus all appear to occur in exclamations. In contrast, the long nuclear fall is a recurrent feature of paroxytonic phrases. The examples given in this section are all from S.s monologue, which contains sufficient examples of this contour to allow quantitative analysis.

Palenquero intonation

26

In the example in Figure 13, the phrases pa sal ri Palnge to get out of Palenque and pa Katahna to Cartagena both exhibit a long nuclear fall. Two additional examples with the same contour are shown in Figures 14 and 15.

200

pa sa l ri pa 0 0

ln ge pa ka ta

na 2.5758

Time (s)

Fig. 13. Palenquero: pa to sal get out ri Palnge, pa of Palenque to Katahna (S.) Cartagena

to get out of Palenque, to Cartagena

Palenquero intonation

27

200

ku 0 0

ma

hn

de 1.18129

Time (s)

Fig. 14. Palenquero: ku t ma hnde (S.) with all these PL people with all these people = with everyone (Sp. con toda esa gente)

Palenquero intonation

28

200

di ma 0 0

ks

na

ngn

de 1.89163

Time (s)

Fig. 15. Palenquero: di of this ma ks asna ngnde (S.) PL thing this big

of those things, big like this One of the striking features of the contour illustrated in Figures 4 and 13-15 is the extraordinary lengthening of the last stressed syllable. In a study of syllable duration in Spanish, Clegg & Fails (1987) find that stressed syllables are, on average, 50% longer than unstressed ones. We have identified and analyzed 44 phrases bearing a long nuclear fall in S.s recording, all with phrase-penultimate stress. The average duration of the penultimate syllables is 388.48 ms. (st. dev. 67.05 ms.), whereas the antepenultimate syllable has an average duration of 139.08 ms. (st. dev. 40.28 ms.). [fn 13]. That is, the nuclearly accented syllable in phrases with the long nuclear fall contour is more than 2.5 times (or 285%) longer than the preceding one. These results are roughly in line with those obtained by Kaisse (2001) in a study of a somewhat similar contour, the Argentinian long fall. The Palenquero long fall differs from its Argentinian counterpart in several respects. First, it lacks the special pragmatic meaning of the Argentinian contour (item in a discontinuous list or highlighted

Palenquero intonation

29

word, according to Kaisse). The Palenquero long fall seems to be a rather neutral nuclear accent configuration when born by a word with penultimate accent. Secondly, the Argentinian contour has its fall entirely within the stressed syllable, while Palenquero keeps the accented syllable high if open, with the fall becoming initiated after the tonic. We have provided syllable durations so as to facilitate comparisons with published results on Spanish. A more accurate view can be obtained by limiting comparison to the duration of the vowels, as the consonant margins introduce uncontrolled variability (as it is the case in the studies cited). To that end, Table 1 provides mean duration values (with standard deviation in parentheses) for the last three vowels in the 44 utterances we are examining in this section. From these calculations we have excluded accented vowels in antepenultimate position (6 tokens, e.g. kot plnda to cut bananas). As shown in the table, vowels in accented syllables bearing a nuclear long fall tend to have roughly twice the duration of vowels in immediately preceding and following unaccented syllables.

pretonic /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ /u/ ALL V Table 1.

89.5 110.6 100.9 98.5 131.2 106.8 (10) (25.6) (2) (21.9) (0) (34.5)

N 21 4 4 8 1 38

tonic

244.8 204.7 199.1 198.1 157.7 188.0 (57.9) (4.7) (38) (19.9) (20.4) (22.3)

N 9 25 5 2 3 44

posttonic

103.8 (5.9) 95.7 (3.5) 168.8 (20.4) 68.4 (7.5)

--99.9 (24.1)

N 11 13 3 17 --44

Average duration (in ms., standard deviations in parentheses) of vowels in pretonic, tonic and posttonic (final) position in phrases with a long nuclear fall contour.

Palenquero intonation

30

5. Interrogative intonation Palenquero does not make use of Spanish-like subject-verb inversion (thus Pal. kundo bo kel bae? lit. when you want [to] go?, but never *kundo kel bo bae?). Because of the absence of subject-verb inversion, intonation is crucial in the creole for signalling questions, especially yes-no questions. [fn. 14] In interrogative Palenquero sentences, we find the characteristic Caribbean Spanish circumflex pattern, with upstepping of the final accent and a final fall (Sosa, 1999: 203-209), instead of the final rise found in other Spanish dialects that we illustrated in Figure 2. This section offers four Palenquero examples of interrogative contours. Two end with a paroxytonic word, mtte Tuesday (Fig. 16) and slo alone (Fig. 17). The sentence in Figure 16 is a negative yes-no question: mana n- mtte? isnt tomorrow Tuesday?. Figure 17 shows a pronominal (wh) question: kmo ut tn deh m y slo? How [is it that] you are going to leave me alone? (notice that the subject pronoun ut you is in preverbal position). These examples exhibit typical circumflex patterns. The contour reaches a high peak on the penultimate syllable, and drops off rapidly on the final syllable. The other two examples of interrogative sentences in this section exhibit oxytonic endings: nas to be born (Fig. 18) and a there (Fig. 19). In these examples, the pitch remains high on the last syllable. Figure 18 illustrates a pronominal question functioning as a check: lo k nas? [the day] when I was born?. This sentence ends with a level contour. Each of the four syllables has the following durations: /lo/ = 188 ms, /ki/ = 218 ms, /na/ = 211 ms, /s/ = 400 ms. Notice that the last syllable is twice as long as the other syllables. The example i si y- pel por a? and what if I get lost around there? (Fig. 19) is a question with exclamatory force. The final contour is slightly more complex, with a small fall after the peak on the last syllable, but without a drop off to the intonational floor.

Palenquero intonation

31

500

ma n~a' na nu'e 0 0

ma'

tte 1.07754

Time (s)

Fig.16. Palenquero: mana n mtte? (R.) tomorrow NEG is Tuesday isnt tomorrow Tuesday?

Palenquero intonation

32

500

ko mo u te' ta'n deha' mi' yo' 0 0 Time (s)

Fig. 17.

so'

lo 1.60443

Palenquero: Kmo ut tn deh m how you (s). FUT leave me

y slo? (R.) I alone

How [is it that] you are you going to leave me alone?

Palenquero intonation

33

500

lo 0 0

k-i'

na Time (s)

se' 1.30696

Fig. 18.

Palenquero: lo k that I

nas? (V.) to be born

[the day] when I was born? lo = 188 ms, ki = 218 ms, na = 211 ms, s = 400 ms

Palenquero intonation

34

500

i si y-a' 0 0

pe

le'

por

i' 1.37232

Time (s)

Fig. 19. Palenquero: i si and if yI pel T/A lose por a? (R.) around there

and what if I get lost around there?

Palenquero intonation

35

By employing a circumflex interrogative pattern, Palenquero emulates a pattern that is standard in Caribbean Spanish. It should be noted, however, that this contour allows for the realization of a H tone on the last accented syllable. This is contrary to the rising contour of yes-no interrogatives found in Castilian, Mexican, and other wellknown varieties of Spanish (see Sosa, 1999), where the syllable with nuclear accent bears a L tone, as illustrated earlier in Figure 2. This is thus a case where prosodic convergence with regional Spanish is possible without weakening the connection between stress and H tone.

5. Summary and discussion of origins In the preceding sections we have noted a number of features where Palenquero prosody differs from Spanish. Most important among these are: (a) The systematic association in Palenquero of accented syllables with level H tones, in declarative and interrogative sentences as well as both in nuclear and prenuclear positions. The frequent absence of final falls in declaratives with oxytonic endings. The downstep of phrase-final H tones to a level M tone.

(b) (c)

One could analyze Palenquero as essentially a tone language, as has been suggested by Devonish (1989, 2002) and other investigators for several Atlantic creoles (including Iberian-based Papiamentu, as analyzed by Rmer, 1991; Rivera-Castillo, 1998; RiveraCastillo & Pickering, 2004). In such an analysis, Palenquero function words may be either H-toned or toneless, thereby generally corresponding to the contrast between unstressed and stressed forms in Spanish. All other words would bear a lexical H-tone on one of the syllables, which is again the stressed syllable of the corresponding Spanish word, in the lexicon of Spanish origin. In this way, Palenquero would also be similar to Nubi, an Arabic-lexified creole spoken in Uganda (Gussenhoven, 2005) as well as restricted-tone languages such as Somali (Hyman, 1981). Typologically, however, Palenquero is still closer to being an accentual language than a tone language since (a) there can be only one H-toned syllable per word, and (b) every lexical word has a Htoned syllable (there are no toneless words, except for some function words). This latter

Palenquero intonation

36

feature makes it unlike Somali and Nubi, which also have one H tone per word, but have rules deleting underlying H tones in certain phonological contexts (Somali also has a class of underlyingly unaccented verb forms). Palenquero lacks the lexical tonal contrast superimposed on stress that is found in Papiamentu, the other Iberian-lexicon creole of South America. As Remijsen & van Heuven (2005) demonstrate, Papiamentu is a stress-accent language with an added pitchaccent contrast, not very different from that found in Swedish (Bruce, 1977; Gussenhoven, 2004: 209-216). Guyanese Creole and some other Anglo-West African varieties possess a similar lexical pitch-accent contrast (see Devonish, 2002: 165-180). In the final analysis, we find ourselves in agreement with Patios (1983, 2002) position that Palenquero is best analyzed as an accentual language, rather than as a language with lexical tone. However, Palenquero differs more than Spanish from the stress-accent language prototype represented by English, and is closer to being a tonalaccent language. Moino (2001), in an unpublished conference paper, appears to adopt a similar view, describing Palenquero as possessing a tonal-accentual system. He offers a similar conclusion in print, albeit only in passing [fn 15] (Moino 2002: 247; see also 2005). The very high frequency with which accented syllables bear a H tone, and the other properties listed above contribute to making Palenquero prosody impressionistically very different from that of standard and even regional varieties of Spanish. We may ask now whether it is reasonable to attribute the peculiar intonational features of Palenquero to substrate influence. That is, could these features be due to the fact that, during the formative period of the creole, a majority of its users were native speakers of Bantu languages (specifically, it appears, from the Kikongo group)? Most Bantu languages have a lexical opposition between H and L, better characterized for many of the languages as a privative contrast between H-toned and toneless syllables (Kisseberth & Odden, 2003: 59). Bantu languages in general are also well-known for having many complex phenomena of tonal assimilation and other alternations (for Kikongo, in particular, see, Carter, 1980; Odden, 1994; Blanchon, 1998, among others). Palenquero has not adopted this sort of complex tonology, although the lowering of final H tones to M can be analyzed as a tone rule. The consistency with which accented syllables are realized with a high pitch (reaching a peak within the syllable), leads us to conclude that, at some point in the past, Palenqueros reinterpreted Spanish stress as requiring an association with a lexical H tone, as has been claimed for several English-lexicon creoles (see Carter, 1987; Devonish, 2002, among others). This would have involved the interpretation of the intonational contours of Spanish words in citation form (or in nuclear position) as word-level tone. As

Palenquero intonation

37

Devonish states it, the general hypothesis is that [g]iven the appropriate circumstances, sentence level intonation may become reinterpreted as a tone melody associated with an individual word (2002: 36). We believe that this hypothesis may explain the intonational features that make Palenquero different from (Caribbean) Spanish. The reinterpretation of Spanish stress as a lexical H tone is indeed what one would, in principle, expect, if most of the first users of Palenquero were native speakers of Kikongo and other Bantu lexical-tone languages. Within this context it is relevant to note that Kikongo imports Portuguese borrowings by adapting them with a H tone on the syllable that bears lexical stress in Portuguese (Carter, 1987: 246-247), and the same adaptation has been reported in borrowings from English into several Bantu and West African languages (Carter, 1987). Some of the most striking features of Palenquero intonation are replicated in the Spanish of Equatorial Guinea, where most speakers have a Bantu language as their native tongue. Thus Quilis & Casado-Fresnillo (1995: 138), comparing the Spanish intonation of their Equatorial Guinea informants with that of Madrid Spanish, find that Equatorial Guinea Spanish has very little declination, more ups and downs in pitch, and also level endings. This coincides with our findings for Palenquero. Lipski also notes that in Equatorial Guinea Spanish [m]any declarative sentences end on a mid or high tone, and occasionally even on a rising tone, in contrast to native non-African varieties of Spanish (2005: 212). Lipski concludes that [i]n the case of Spanish as phonologically restructured by speakers of Bantu languages in Equatorial Guinea (all of which use a basic two-tone system), it appears that many instances of lexical stress accent in Spanish have been reinterpreted as lexically preattached High tone (2005:212). In our view, these similarities in intonation between Equatorial Guinea Spanish and Palenquero are best explained as the result of a common initial set of circumstances, where native speakers of tonal Bantu languages were exposed to Spanish prosody as adults. That is, the reinterpretation of Spanish prosody that appears to have taken place in Equatorial Guinea Spanish also occurred in the initial development of the Palenquero creole. This overall scenario, in which Spanish stress and sentence-level prosody are reinterpreted in terms of lexical tone, is consistent with the evidence for another phonological reinterpretation, at the segmental level. As noted in the introduction, certain changes in the shape of words of Spanish origin appear to indicate that the Spanish phonological alternation between the initial voiced stops [b-, d- g-] and the intervocalic voiced fricatives or approximants [--, --, --] was initially reinterpreted in terms of the typical Bantu alternation between initial [mb-, nd-, g-] and intervocalic [--, -l-, --]. At

Palenquero intonation

38

both the suprasegmental and the segmental levels, the original members of the Palenquero community filtered Spanish phonology through the lens of their native Bantu phonology. As discussed in section 4.4, accented phrase-penultimate syllables are extraordinarily lengthened under the long nuclear fall contour. [fn 16] On the other hand, we have also noted that often there is very little or no stress-related lengthening in neutral declarative sentences with an oxytonic ending. Given the fact that phrasepenultimate lengthening is a widespread feature in Bantu languages (see, for instance, Myers, 2003), it would not be unreasonable to attribute the peculiar Palenquero durational pattern in stressed phrase-penultimate syllables to the Bantu substrate as well. [fn 17] A final caveat: the findings of this paper are based on somewhat dated recordings of Palenquero. As we noted in section 2, the traditional Palenquero tonillo is much less noticeable in the speech of younger contemporary speakers. The intonational patterns of Palenquero that originally struck researchers in the 1960s and 70s may thus be less apparent to those venturing into the community at the beginning of the 21st century.

References Amayo, A. (1980) Tone in Nigerian English. Chicago Linguistic Society, 16, 1-9. Beckman, M. & Pierrehumbert, J. (1986) Intonational structure in English and Japanese. Phonology Yearbook, 3, 255-310. Becerra, S. (1985) Fonologa de las consonantes implosivas en el espaol urbano de Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). Bogota: Publicaciones del Instituto Caro y Cuervo. Beckman, M., Daz-Campos, M., McGory, J. T. & Morgan, T. (2002) Intonation across Spanish in the Tones and Break Indices framework. Probus, 14, 9-36. Bickerton, D. & Escalante, A. (1970) Palenquero: A Spanish-based creole of northern Colombia. Lingua, 24, 254-267. Blanchon, J. A. (1998) Semantic/pragmatic conditions on the tonology of the Kongo noun-phrase: A diachronic hypothesis. In L. M. Hyman & C. W. Kisseberth (Eds.), Theoretical aspects of Bantu tone (pp. 1-32). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Palenquero intonation

39

Boersma, P. & Weenink, D. (1999-2005) PRAAT: Doing phonetics by computer. http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ Bruce, G. (1977) Swedish word accents in sentence perspective. Lund: Gleerup. Carter, H. (1980) The Kongo tonal system revisited. African Languages Studies, 17, 1-32. Carter, H. (1987) Suprasegmentals in Guyanese: Some African comparisons. In G. Gilbert (Ed.), Pidgin and creole languages (pp. 213-263). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Clegg, J. H. & Fails, W. C. (1987) On syllable length in Spanish. In T. A. Morgan, J. F. Lee & B. VanPatten (Eds.), Language and language use: Studies in Spanish dedicated to Joseph H. Matluck, (pp. 69-78). Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Colantoni, L. (2005) Alignment of nuclear and prenuclear accentual peaks in Buenos Aires Spanish. Presented at 2nd Spanish ToBI Workshop, Barcelona, June 22, 2005. Devonish, H. (1989) Talking in tones: A study of tone in Afro-European creole languages. London & Christ Church, Barbados: Karia Press & Caribbean Academic Publications. Devonish, H. (2002) Talking rhythm stressing tone: The role of prominence in AngloWest African Creole languages. Kingston, Jamaica: Arawak. Elordieta, G. (2003) The Spanish intonation of speakers of a Basque pitch-accent dialect. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 2, 67-95. Face, T. (2003) Intonation in Spanish declaratives: Differences between lab speech and spontaneous speech. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 2, 115-131. Granda, G. de (1968) La tipologa criolla de dos hablas del rea lingstica hispnica. Thesaurus, 23, 193-205. Granda, G. de (1978) Estudios lingsticos hispnicos, afrohispnicos y criollos. Madrid: Gredos. Granda, G. de (1994) Espaol de Amrica, espaol de frica y hablas criollas hispnicas. Madrid: Gredos. Guitart, J. (1976) Markedness and a Cuban dialect of Spanish. Washington: Georgetown University Press. Gussenhoven, C. 2004. The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gussenhoven, C. (2005) The prosody of the Nubi verb. Poster presented at Between Tone and Stress, Leiden, June 2005.

Palenquero intonation

40

Hualde, J. I. (2002) Intonation in Spanish and the other Ibero-Romance languages: Overview and status quaestionis. In C. Wiltshire & J. Camps (Eds.), Romance phonology and variation. Selected papers from the 30th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, Gainesville, Florida, February 2000 (pp. 101-115). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Hualde, J. I. (2003). El modelo mtrico y autosegmental. In P. Prieto (Ed.), Teoras de la entonacin, (pp. 155-184). Barcelona: Ariel. Hualde, J. I. (2005) The sounds of Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hyman, L. (1981) Tonal accent in Somali. Studies in African Linguistics, 12, 169-203. Hyman, L. (2003) Segmental phonology. In D. Nurse & G. Philippson (Eds.), pp. 42-58. Kaisse, E. (2001) The long fall: an intonational melody of Argentinian Spanish. In J. Herschensohn, E. Malln & K. Zagona (Eds.), Features and interfaces in Romance, 147-160. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Katamba, F. (2003) Bantu nominal morphology. In D. Nurse & G. Philippson (Eds.), pp. 103-120. Kisseberth, C. & Odden, D. (2003) Tone. In D. Nurse & G. Philippson (Eds.), pp. 59-70. Ladd, D. R. (1996) Intonational phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Leyden, K. van (2004) Prosodic characteristics of Orkney and Shetland dialects: An experimental approach. Utrecht: LOT. Lipski, J. (1992) Spontaneous nasalization in the development of Afro-Hispanic language. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 7, 261-305. Lipski, J. (1994) Latin American Spanish. London / New York: Longman. Lipski, J. (2005) A history of Afro-Hispanic language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Maddieson, I. (2003) The sounds of the Bantu languages. In D. Nurse & G. Philippson (Eds.), pp. 15-41. Megenney, W. (1986) El palenquero: un lenguaje post-criollo de Colombia. Bogota: Caro y Cuervo. Montes, J. J. (1962) Sobre el habla de San Basilio de Palenque. Thesaurus, 17, 446-450. Moino, Y. (2001) Le palenquero de Colombia: langue accentuelle ou langue tonale? Paper presented at ACPBLE, Coimbra, Portugal. Moino, Y. (2002) Las construcciones de genitivo en palenquero: una semantaxis africana? In Y. Moino & A. Schwegler (Eds.), pp. 227-248. Moino, Y. (2003) Lengua e identidad afroamericana: el caso del criollo de Palenque de San Basilio (Colombia). In C. Als & J. Chiappino (Eds.) Caminos cruzados. Ensayos en antropologa social,

Palenquero intonation

41

etnoecologa y etnoeducacin (pp. 517-531). Mrida: IRD Editions-ULA GRIAL. Moino, Y. (2005) Cruces lingsticos iberocongoleses en palenquero: integrarse a la sociedad mayoritaria o distinguirse de ella? Paper presented at Congreso de la Asociacin Alemana de Hispanistas: Fronteras, construcciones y trangresiones de fronteras, Universitt Bremen, March 2005. Moino, Y. & Schwegler, A. (Eds.) (2002) Palenque, Cartagena y Afro-Caribe: Historia y lengua. Tbingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. Myers, S. (2003) F0 timing in Kinyarwanda. Phonetica, 60, 71-97. Navarro Toms, T. (1977) Manual de pronunciacin espaola, 19th ed. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientficas (Publicaciones de la Revista de Filologa Espaola, [4th ed., 1932]). Nieves Oviedo, R. (2002) Sobre la asimilacin de consonantes en algunas reas de la Costa Atlntica colombiana (Crdoba, Sucre, Bolvar). In Y. Moino & A. Schwegler (Eds.), pp. 257-266. Nez Cedeo, R. (1987) Intervocalic /d/ rhotacism in Dominican Spanish: A non-linear analysis. Hispania, 70, 363-368. Nurse, D. & Philippson, G. (Eds.) (2003) The Bantu languages. London: Routledge. ORourke, E. (2004) Peak placement in two regional varieties of Peruvian Spanish intonation. In J. Auger, J. C. Clements & B. Vance (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to Romance linguistics (pp. 321-341). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Odden, D. (1994) Syntactic and semantic conditions in Kikongo phrasal phonology. In J. Cole & C. Kisseberth (Eds.), Perspectives in phonology (pp. 167-201). Stanford, CA: CSLI. Patio Roselli, C. (1983) El habla en El Palenque de San Basilio. In N. S. de Friedemann & C. Patio Roselli, Lengua y sociedad en El Palenque de San Basilio (pp. 85-287). Bogota: Caro y Cuervo. Patio Roselli, C. (2002) Sobre y composicin del criollo palenquero. In Y. Moino & A. Schwegler (Eds.), pp. 21-33. Pierrehumbert, J. (1980) The phonology and phonetics of English intonation. PhD dissertation, MIT. Prieto, P., Santen, J. van & Hirschberg, J. (1995) Tonal alignment patterns in Spanish. Journal of Phonetics, 23, 429-451. Prieto, P., Shih, C. & Nibert, H. (1996) Pitch downtrend in Spanish. Journal of Phonetics, 24, 445-473. Quilis, A. (1993) Tratado de fonologa y fontica espaolas. Madrid: Gredos.

Palenquero intonation

42

Qulis, A. & Casado-Fresnillo, C. (1995) La lengua espaola en Guinea Ecuatorial. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educacin a Distancia. Remijsen, B. & Heuven, V. J. van (2005) Stress, tone, and discourse prominence in the Curaao dialect of Papiamentu. Phonology 22: 205-235. Rivera-Castillo, Y. (1998) Tone and stress in Papiamentu: the contribution of a constraint-cased analysis to the problem of creole genesis. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 13, 297-334. Rivera-Castillo, Y. & Pickering, L. (2004) Phonetic correlates of stress and tone in a mixed system. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 19, 261-284. Rmer, R. G. (1991) Studies in Papiamentu phonology. Amsterdam & Kingston: Caribbean Culture Studies. Schwegler, A. (1992) Hacia una arqueologa afrocolombiana: Restos de tradiciones religiosas bantes en una comunidad negroamericana. Amrica Negra, 4, 5-82. Schwegler, A. (1996) Chi ma nkongo: lengua y rito ancestrales en El Palenque de San Basilio (Colombia). 2 vols. Frankfurt/Madrid: Vervuert Verlag. Schwegler, A. (1998) Palenquero. In M. Perl & A. Schwegler, (Eds.), Amrica negra: Panormica actual de los estudios lingsticos sobre variedades criollas y afrohispanas (pp. 220-291). Frankfurt: Vervuert. Schwegler, A. (2002a) El vocabulario africano de Palenque (Colombia): Segunda parte: compendio alfabtico de palabras (con etimologas). In Y. Moino & A. Schwegler pp. 171-226. Schwegler, A. (2002b) On the (African) origins of Palenquero subject pronouns. Diachronica, 19, 273-332. Schwegler, A. (in press a) Bantu elements in Palenque (Colombia): anthropological, archeological and linguistic evidence. To appear in J. B. Haviser & K. C. MacDonald (Eds.), African re-genesis: Confronting social issues in the diaspora. London: University College London Press. Schwegler, A. (in press b) Palenquero. In D. Brown (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier. Schwegler , A. & Green, K. (in press) Palenquero (Creole Spanish). To appear in J. Holm & P. Patrick (Eds.), Comparative creole syntax. London: Battlebridge Publications. Schwegler, A. & Morton, T. (2003) Vernacular Spanish in a microcosm: Kateyano in El Palenque de San Basilio (Colombia). Revista Internacional de Lingstica Iberoamericana (RILI), 1, 97-159. Sosa, J. M. (1999) La entonacin del espaol: su estructura fnica, variabilidad y dialectologa. Madrid: Ctedra.

Palenquero intonation

43

Wald, B. (1987) Swahili and the Bantu languages. In B. Comrie (Ed.), The worlds major languages (pp. 991-1014). New York: Oxford University Press. Yip, M. (2002) Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palenquero intonation

44

Notes

* For comments we are grateful to Steve Byrd, Laura Downing, Yves Moino and three anonymous reviewers of this journal. The remainder are mostly archaisms or ritual vocabulary associated with the funeral tradition known as lumbal (Schwegler, 1996). Incidentally, this is also the prefix in Gabriel Garca Mrquezs fictional Macondo, from the plural of Kikongo (and other Bantu) li-kondo banana tree. This includes the Spanish spoken in Palenque, together with the creole (Schwegler & Morton, 2003). Prenasalization in Palenquero has been described in Patio (1983: 98-103), Granda (1994: 402-403), Schwegler (1998: 264-265), and Schwegler & Morton (2002: 120, 122, 127, 152), and is treated from a wider Afro-Hispanic perspective in Lipski (1992) and (1994: 98-99). The replacement of /d/ with /l/ is studied in Patio (1983: 93-96), Granda (1994: 412-423), and Schwegler & Morton (2002: 113, 135 [Table 1, item 8]). The voicing assimilation of postnasal plosives is described in Patio (1983: 106-107). The very peculiar Palenquero sing-song intonation, one of whose most salient characteristics is the noticeable raising of the tone and the quantitative lengthening of the stressed syllable. The one aspect that, without a doubt, is the most difficult to solve is that of the intonational patterns of Palenquero, which, in some instances, differ from those of Coastal Spanish. This happens where one would expect it, in the tonemes. The immediate question that arises when we hear these differences of intonation relates to the possible link that the anomalous patterns of Palenquero may or may not have with the tonal systems of African languages. At present, this is an unsolvable problem. Participants were aware of the presence of a tape recorder. [] la peculiar entonacin con que hablan los habitantes de San Basilio, de la cual no pueden liberarse cuando utilizan el castellano, lo cual les atrae no pocas burlas fuera del terruo (Patio, 1983: 110). [ the peculiar intonation with which the inhabitants of San Basilio speak and of which they cannot rid themselves when speaking Spanish. This makes them the butt of many jokes outside of their town.] 9 Text adopted from Sosa (1999), who uses it to illustrate intonational contours in a large number of Spanish dialects. Although the example in Figure 1 was produced by the first author of this paper, who is a speaker of Northern-Central Peninsular Spanish, the contour illustrated is typical of most

3 4

7 8

Palenquero intonation

45

Spanish dialects (Caribbean Spanish included), as demonstrated in Sosa (1999), where the reader can find many essentially identical examples for a large number of Spanish varieties. See also ORourke (2004). 10 The nuclear accent is the perceptually most prominent accent in the phrase. In Spanish, this accent is placed on the last content word of the phrase in utterances with broad focus. Prenuclear accents are localized pitch movements preceding the nuclear one. See, for instance, Ladd (1996). In general, we follow the usual conventions in the transcriptions of Palenquero (see, for instance, Patio, 1983). Our main departure from tradition is that, following Moino (2002: 247), we mark stress on all stressed syllables. The phoneme transcribed as <h> is a pharyngeal fricative /h/, which is often realized as voiced [] in intervocalic position (Patio employs Spanish <j> for this sound). The letters <b, d, g> stand for the phonemes /b,d,g/, which, as in Spanish, are realized as continuant segments in most contexts. The letter <y> represents a voiced palatal with fricative and affricate allophones. The letter <r> stands for a rhotic tap, and <rr> for a trill. In standard Spanish, the contrast is neutralized word-initially, where only the trill occurs. In Palenquero, the tap may, however, occur word-initially and preceded by a vowel (as an allophone of /d/), as in pogke ri because of < Sp. porque de. For introductions to the study of tone, see Yip (2002) and Gussenhoven (2004). Final unstressed syllables present difficulties for measuring, as our speaker often devoiced the final vowel, either partially or completely. With this caveat, the average value obtained for the posttonic syllable in the 44 tokens we analyzed is 193.79 (st. dev. 102.32 ms.) Lipski notes that subject preposing in WH- questions has at times been attributed to an earlier AfroHispanic creole, if not directly to African substrate (2005: 262). In Latin America, non-inverted questions are also found in Cuban, Puerto Rican and coastal Colombian Spanish (that of Palenque included). In these areas, Spanish speakers from the Canary Islands and/or Galicia may have introduced the intonation-based strategy for forming yes-no questions. As Lipski (2005: 263) rightly points out, this by no means implies that contact with creoles or African languages may not also have been a contributing factor for the rise of non-inverted yes-no questions. La lengua [palenquera] es fonolgicamente acentual, pero el acento no es de intensidad y se realiza por medio de un tono alto y/o alargamiento de la vocal: justificaremos estas opciones [de trascripcin] en un trabajo en preparacin sobre la prosodia de la lengua criolla. Palenquero is phonologically an accentual language, but the accent is not one of intensity, and is realized by way of a high tone and/or lengthening of the vowel: I will justify these conventions [of transcription] in a paper on Palenquero prosody, currently in preparation.

11

12 13

14

15

Palenquero intonation

46

16

The lengthening of the stressed phrase-penultimate syllable in interrogatives is also visually detectable in the example in Figure 17, kmo ut tn deh m y slo? How [is it that] you are going to leave me alone? (/y/ = 145 ms, /s/ = 227 ms, /lo/ = 189 ms). The influence of the substrate on durational (as well as intonational) patterns is demonstrated by van Leyden (2004) in an experimental study of the prosodic characteristics of the Shetland dialect (Scotland), which has a Scandinavian substrate.

17

End of document

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Maria Lilia F. Realubit. Translating Vocabulario de La Lengua...Document3 pagesMaria Lilia F. Realubit. Translating Vocabulario de La Lengua...imanolkioPas encore d'évaluation

- Team Chada: Nicamar Angel L. Arsenio Rolando B. Acosta Narlina A. Espanto Jannet B. Dacanag John Lito B. YaoDocument14 pagesTeam Chada: Nicamar Angel L. Arsenio Rolando B. Acosta Narlina A. Espanto Jannet B. Dacanag John Lito B. YaoLui Harris S. CatayaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ergative Analyis of MasbatenyoDocument13 pagesErgative Analyis of MasbatenyoMihael RoseroPas encore d'évaluation

- Colonialism and Resistance - A Brief History of Deafhood - Paddy LaddDocument11 pagesColonialism and Resistance - A Brief History of Deafhood - Paddy Laddאדמטהאוצ'וה0% (1)

- Haugen Analysis Linguistic BorrowingDocument23 pagesHaugen Analysis Linguistic BorrowingInpwPas encore d'évaluation

- DIXON - DemonstrativesDocument52 pagesDIXON - DemonstrativeslauraunicornioPas encore d'évaluation

- BEFORE NIGHT COMES: Narrative and Gesture in Berio's Sequenza III (1966)Document10 pagesBEFORE NIGHT COMES: Narrative and Gesture in Berio's Sequenza III (1966)Elena PlazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Constantino Tagalog and Other Philippine LanguagesDocument43 pagesConstantino Tagalog and Other Philippine LanguagesFeed Back ParPas encore d'évaluation

- Lipski 2015 Spanish PalenqueroDocument13 pagesLipski 2015 Spanish PalenqueroNaydelin BarreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Quechua Language Shift, Maintenance, and Revitalization in The Andes - The Case For Language PlanningDocument62 pagesQuechua Language Shift, Maintenance, and Revitalization in The Andes - The Case For Language PlanningFelipe TabaresPas encore d'évaluation

- Language EcologyDocument19 pagesLanguage EcologyElviraPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Language and CultureDocument81 pagesIntroduction To Language and CultureJulieth CampoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Dialectology of Cebuano Bohol Cebu and DavaoDocument13 pagesThe Dialectology of Cebuano Bohol Cebu and DavaoEya ApostolPas encore d'évaluation

- LiteratureDocument21 pagesLiteratureMylene Sunga AbergasPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Literature by Frank R. Blake (9pages)Document9 pagesPhilippine Literature by Frank R. Blake (9pages)May RusellePas encore d'évaluation

- John Joseph GumperzDocument29 pagesJohn Joseph GumperzAsma GharbiPas encore d'évaluation

- Learner's Activity Sheet Assessment Checklist: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and To The World - Week 1Document11 pagesLearner's Activity Sheet Assessment Checklist: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and To The World - Week 1Asna MpPas encore d'évaluation

- IbanagReferencegrammar PDFDocument359 pagesIbanagReferencegrammar PDFSimon PechoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Development of Philippine Literature Journey From Pre Colonial To Contemporary TimesDocument28 pagesThe Development of Philippine Literature Journey From Pre Colonial To Contemporary TimesWilson CadientePas encore d'évaluation

- An Experimental Decipherment of The Calatagan PotDocument22 pagesAn Experimental Decipherment of The Calatagan Pot000000000000000Pas encore d'évaluation

- BLL 105 Final PaperDocument6 pagesBLL 105 Final PaperApril Ezra MoulicPas encore d'évaluation

- I.Objectives: Diaries/verbal-Communication-And-Its-TypesDocument6 pagesI.Objectives: Diaries/verbal-Communication-And-Its-TypesSharie MagsinoPas encore d'évaluation

- In An Ocean of Emotions:: Philippine DramaDocument16 pagesIn An Ocean of Emotions:: Philippine DramaJasmine AlmeroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Story of An Orphan GirlDocument1 pageThe Story of An Orphan GirlArvi ChuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Identity and Investment in The PDFDocument15 pagesLanguage Identity and Investment in The PDFAurora Tsai100% (1)

- Sorsogon State University Sorsogon City Campus: BS EN 9001:2015Document10 pagesSorsogon State University Sorsogon City Campus: BS EN 9001:2015Jeremy EngayPas encore d'évaluation

- Lenore A. Grenoble Lindsay J. Whaley Saving - Languages An Introduction To Language RevitalizationDocument245 pagesLenore A. Grenoble Lindsay J. Whaley Saving - Languages An Introduction To Language RevitalizationRatnasiri ArangalaPas encore d'évaluation

- General Morphological Processes Involved in The Formation of New WordsDocument3 pagesGeneral Morphological Processes Involved in The Formation of New WordsGazel Villadiego Castillo100% (1)

- Criteria For Dance BattleDocument2 pagesCriteria For Dance BattleseadiabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On After Babel by George SteinerDocument26 pagesNotes On After Babel by George Steinerluzmoreira8448Pas encore d'évaluation

- Baybayin BillDocument2 pagesBaybayin BillJohn Joshua Azucena100% (1)

- Smaller and Smaller CirclesDocument1 pageSmaller and Smaller CirclesLUZ BACCAYPas encore d'évaluation

- Cummins 1981 Age On Arrival and Immigrant Second Language Learning in CanadaDocument18 pagesCummins 1981 Age On Arrival and Immigrant Second Language Learning in CanadaCharles CorneliusPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Volume 10: Research Methods in Language and Education Au1Document8 pagesIntroduction To Volume 10: Research Methods in Language and Education Au1Mhaye CendanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 7 1st QuarterDocument68 pagesModule 7 1st QuarterKim Joshua Guirre DañoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 Filgr7q3Document122 pages2019 Filgr7q3Jenalyn TayamPas encore d'évaluation

- English 7 Pre Assessment Material FINAL COPY With Question CategoriesDocument3 pagesEnglish 7 Pre Assessment Material FINAL COPY With Question CategoriesJopao PañgilinanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Phonetic Structures of Kalanguya (University of The Philippines, Diliman Undergraduate Thesis, 2010)Document11 pagesThe Phonetic Structures of Kalanguya (University of The Philippines, Diliman Undergraduate Thesis, 2010)Paul Julian Santiago100% (1)

- 21st Cen. Lit. Long Quiz ReviewerDocument9 pages21st Cen. Lit. Long Quiz ReviewerFuntastic PaulPas encore d'évaluation

- Gay Lingo-June 27Document23 pagesGay Lingo-June 27John BarbaPas encore d'évaluation

- A. KirkpatrickDocument4 pagesA. Kirkpatrickerinea081001Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Game of Naming: A Case of The Butuanon Language and Its Speakers in The PhilippinesDocument21 pagesThe Game of Naming: A Case of The Butuanon Language and Its Speakers in The PhilippinesAbby GailPas encore d'évaluation

- MODULE 2 - Culture and SocietyDocument6 pagesMODULE 2 - Culture and Societyjoy castillo100% (1)

- Cabral Kokama1995Document427 pagesCabral Kokama1995Jamille Pinheiro DiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Language and Space Theories and MethodsDocument17 pagesLanguage and Space Theories and MethodsAide Paola Ríos100% (1)

- COURSE SYLLABUS in (Code - Descriptive Title)Document7 pagesCOURSE SYLLABUS in (Code - Descriptive Title)Fernando BornasalPas encore d'évaluation

- The Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccDocument13 pagesThe Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccFabian KoLPas encore d'évaluation

- Chavacano Language PDFDocument1 pageChavacano Language PDFJerald Abian SujitadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Language Diversity and English in The Philippines by Curtis McFarlandDocument23 pagesLanguage Diversity and English in The Philippines by Curtis McFarlandJhy-jhy OrozcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mimetic TheoryDocument2 pagesMimetic TheorybozPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonological and Morphological Analysis of The PhilippineDocument13 pagesPhonological and Morphological Analysis of The PhilippineCprosal Pabalinas Cheryl100% (1)

- Palenquero LanguageDocument8 pagesPalenquero Languagenuno100% (1)

- Mexico City SpanishDocument8 pagesMexico City SpanishКирилл КичигинPas encore d'évaluation

- Variation in Palatal ProductionDocument11 pagesVariation in Palatal ProductionEster PiscorePas encore d'évaluation

- An Articulator y View of Historical S-Aspiration in SpanishDocument12 pagesAn Articulator y View of Historical S-Aspiration in SpanishJorge MoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Erik Boot Vocabulary in The Cholti Language Resistance2010 PDFDocument46 pagesErik Boot Vocabulary in The Cholti Language Resistance2010 PDFMarcusAugustusVPas encore d'évaluation

- Mennonite PlauttdietschDocument25 pagesMennonite PlauttdietschSenzei Sariel HemingwayPas encore d'évaluation

- Trudgill Spanish SDocument28 pagesTrudgill Spanish SPsaxtisPas encore d'évaluation

- Root Affix AsymmetriesDocument30 pagesRoot Affix Asymmetriessergio2385Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vietnamese (Hanoi Vietnamese) : Illustration of The IpaDocument16 pagesVietnamese (Hanoi Vietnamese) : Illustration of The IpaLong MinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Hualde y Prieto 2002Document10 pagesHualde y Prieto 2002bodoque76Pas encore d'évaluation

- Phonotactic Rules With Foreign WordsDocument2 pagesPhonotactic Rules With Foreign WordsSattar KhattawyPas encore d'évaluation

- Learn HangulDocument11 pagesLearn HanguldesireeuPas encore d'évaluation

- Hum 102 Essentials of Communication: Session1Document74 pagesHum 102 Essentials of Communication: Session1Himanshu SukhejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Consonant Sounds Surprise TestDocument3 pagesConsonant Sounds Surprise Testinger polaPas encore d'évaluation

- All-VA Chorus Auditions Adjudication Form PDFDocument1 pageAll-VA Chorus Auditions Adjudication Form PDFmELISSAPas encore d'évaluation

- Aur Mushkil Asan Ho GayeDocument96 pagesAur Mushkil Asan Ho Gayesunnivoice100% (3)

- Gujarati ShorthandDocument563 pagesGujarati ShorthandVatsal Dave83% (6)

- Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Del Sur Good Sheperd College IncDocument6 pagesBangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Del Sur Good Sheperd College IncQuenie BarreraPas encore d'évaluation

- A Synchronic Comparison Between The Vowel Phonemes of Bengali & English Phonology and Its Classroom ApplicabilityDocument31 pagesA Synchronic Comparison Between The Vowel Phonemes of Bengali & English Phonology and Its Classroom ApplicabilityAnkita DasPas encore d'évaluation

- Holy Quran para 1 PDFDocument27 pagesHoly Quran para 1 PDFmunna99100% (8)

- Alliteration RevisionDocument1 pageAlliteration Revisionjavier9786Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jamia Hafsa Ka Waqia by Maulana Zahid Ur RashidiDocument130 pagesJamia Hafsa Ka Waqia by Maulana Zahid Ur RashidiShahood AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- LinksAmE1 8Document3 pagesLinksAmE1 8Oswaldo AlexisPas encore d'évaluation

- Belting en Studie I Syn Och ArbetssättDocument46 pagesBelting en Studie I Syn Och Arbetssättjanina821Pas encore d'évaluation

- Principles of Speech DeliveryDocument5 pagesPrinciples of Speech DeliveryKat PingolPas encore d'évaluation

- Spelling RulesDocument5 pagesSpelling RulesvijthorPas encore d'évaluation

- Intonation Practice O'Connor - Arnold PDFDocument12 pagesIntonation Practice O'Connor - Arnold PDFmariana100% (1)

- Session 5 - Phonological RulesDocument16 pagesSession 5 - Phonological RulesSuong Trong Mai HoangPas encore d'évaluation

- Vocal Exercises To Improve ProjectionDocument7 pagesVocal Exercises To Improve ProjectionNiño Joshua Ong BalbinPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech and Language ImpairmentDocument4 pagesSpeech and Language ImpairmentVia Iana RagayPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 Speech Organs Vowels 2 PDFDocument3 pagesLesson 1 Speech Organs Vowels 2 PDFsami karem100% (1)

- Definition of VowelsDocument5 pagesDefinition of VowelsHillary NduPas encore d'évaluation

- Place of ArticulationDocument3 pagesPlace of ArticulationCo Bich Cshv100% (1)

- Q3 English 7 Module 2Document32 pagesQ3 English 7 Module 2Nicole Claire Tan Dazo50% (2)

- Final CSEC ORAL EXAMINATION 2020 - Virtual ClassDocument40 pagesFinal CSEC ORAL EXAMINATION 2020 - Virtual Classdijojnay100% (2)

- A Start in PunjabiDocument159 pagesA Start in PunjabiManleen KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- Arpabet PDFDocument4 pagesArpabet PDFNoob AkayPas encore d'évaluation

- English Pronunciation For Spanish SpeakersDocument5 pagesEnglish Pronunciation For Spanish SpeakersbenmackPas encore d'évaluation

- L4 Descript of VOWELS-1Document34 pagesL4 Descript of VOWELS-1Ménessis CastilloPas encore d'évaluation