Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

FKFFKFK

Transféré par

kennerbobTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

FKFFKFK

Transféré par

kennerbobDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

hilip Parsons, writing in 1771, described how it was carried out in England: In the Northern parts of England it is no unusual

diversion to tie a rope across a street and let it swing about the distance of ten yards from the ground. To t he middle of this a living cock [sic] is tied by the legs. As he swings in the a ir, a set of young people ride one after another, full speed, under the rope, an d rising in the stirrups, catch at the animal's head, which is close clipped and well soaped, in order to elude the grasp. Now he who is able to keep his seat i n his saddle, and his hold of the bird's head, so as to carry it off in his hand , bears away the palm, and becomes the noble hero of the day.[4] The sport was challenging, as the oiling of the goose's neck made it difficult t o retain a grip on it, and the bird's flailing made it difficult to target in th e first place. Sometimes the organisers would add an extra element of difficulty ; one writer witnessed "a nigger, with a long whip in hand ... stationed on a st ump, about two rods [10 m / 32 ft] from the gander, with orders to strike the ho rse of the puller as he passed by." The reaction of the startled horse would mak e it even more difficult for the puller to grab the goose as he went by. Many ri ders missed altogether; others broke the goose's neck without snapping off the h ead.[5] The American poet and novelist William Gilmore Simms wrote that It is only the experienced horseman, and the experienced sportsman, who can poss ibly succeed in the endeavor. Young beginners, who look on the achievement as ra ther easy, are constantly baffled; many find it impossible to keep the track; ma ny lose the saddle, and even where they succeed in passing beneath the saplings without disaster, they either fail altogether in grasping the goose, which keeps a constant fluttering and screaming; or, they find it impossible to retain thei r grasp, at full speed, upon the greasy and eel-like neck and head which they ha ve seized.[6] Goose pulling is attested in the Netherlands as early as the start of the 17th c entury; the poet Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero referred to it in his 1622 poem Boer engeselschap ("Company of Peasants"), describing how a party of peasants going t o a goose-pulling contest near Amsterdam end up in a brutal brawl, leading to th e lesson that it is best for townspeople to stay away from peasant pleasures.[7] The Dutch settlers of North America brought it to their colony of New Netherlan d and from there it was transmitted to English-speaking Americans. Goose-pulling was taken up by those at the lower levels in American society,[2] though it cou ld attract the interest of all social strata. In the pre-Civil War South, slaves and whites competed alongside each other in goose-pulling contests watched by " all who walk in the fashionable circles."[8] Charles Grandison Parsons described the course of one such contest held in Milledgeville, Georgia in the 1850s: At the appointed time, rude whisky tents, and festive seats, and shades, were pr epared around the "pulling course;" and thousands of spectators ladies as well a s gentlemen, the elite as well as the vulgar assembled to engage in or witness t he favorite sport... Tickets were issued by the proprietor of the gander, at fifty cents each, to all gentlemen present who wished for them, and they entered their names as "pullers ". The pullers were to start about ten rods [about 50 m / 165 ft] from the gande r, on horseback, riding at full speed, and as they passed along under the gander , they had the privilege of pulling off his head which would entitle them to the additional privilege of eating him... One entered the list a "gentleman of property and standing" and dashed over the course. The poor gander seeming quite resigned to his fate, or not comprehending his danger, and not knowing how to "dodge" had his neck seized by the first rid er; but being well oiled, and his head so small, and his strength not yet exhaus ted, he slipped his head through the puller's hand without suffering much from t he twist... After this he kept a sharp look out, and many pullers passed by with out being able to grapple his neck. The game went on, and the pullers increased, till the jaded gander could elude their grasp no longer. An old Cracker with a sandpaper glove on pulled off his head at last, amid the shouts of a wondering h ost of intoxicated competitors.[8] The prizes of a goose-pulling contest were trivial often the dead bird itself, o ther times contributions from the audience or rounds of drinks. The main draw of

such contests for the spectators was the betting on the competitors, sometimes for money or more often for alcoholic drinks.[2] One contemporary observer comme nted that "the whoopin', and hollerin', and screamin', and bettin', and exciteme nt, beats all; there ain't hardly no sport equal to it."[9] Goose-pulling contes ts were often held on Shrove Tuesday and Easter Monday, with competitors "engage d in this sport not just for its excitement but also to prove they were "real me n," physically strong, brave, competitive and willing to take risks."[10] Unlike some other contemporary blood sports, goose pulling was often frowned upo n. In New Amsterdam (modern New York) in 1656, Director General Pieter Stuyvesan t issued ordinances against goose pulling, calling it "unprofitable, heathenish and pernicious."[1] Many contemporary writers professed disgust at the sport; an anonymous reviewer in the Southern Literary Messenger, writing in 1836, describ ed goose pulling as "a piece of unprincipled barbarity not infrequently practise d in the South and West."[11] William Gilmore Simms described it as "one of thos e sports which a cunning devil has contrived to gratify a human beast. It appeal s to his skill, his agility, and strength; and is therefore in some degree grate ful to his pride; but, as it exercises these qualities at the expense of his hum anity, it is only a medium by which his better qualities are employed as agents for his worser nature."[6] The sport appears to have been relatively uncommon in Britain, as all references are to it as a curiosity practiced somewhere else. The 1771 Parsons account loc ates it in "Northern parts of England" and assumes it is unknown in Newmarket in Southern England. In a satirical letter to Punch in 1845 it is regarded as a ba rbarous practice known only to the bloodthirsty Spaniards, like bull-fighting.[1 2] The serious work Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain, of 1849, calls it "Goose-riding" and says it has been "practiced in Derbyshire wit hin the memory of persons now living", and that the antiquary Francis Douce (175 71834) had a friend who remembered it "when young" in Edinburgh in Scotland.[13] From these references it would appear to have died out in Britain by the end of the 18th century.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Birthday: Relationship Status: Sex: Interested In:: Duane Earl - Host of Beyond Insemination 326 Days AgoDocument2 pagesBirthday: Relationship Status: Sex: Interested In:: Duane Earl - Host of Beyond Insemination 326 Days AgokennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- TXTHJHJJDocument7 pagesTXTHJHJJkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- SssDocument4 pagesSsskennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- SSDDDocument2 pagesSSDDkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- 33 DDocument2 pages33 DkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- SssssssDocument3 pagesSsssssskennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- GoddysDocument3 pagesGoddyskennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- Boob DdyDocument1 pageBoob DdykennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- SsssssDocument3 pagesSssssskennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- Hello BodyDocument3 pagesHello BodykennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- DoDocument3 pagesDokennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- FfoDocument3 pagesFfokennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- LolDocument1 pageLolkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- ObDocument2 pagesObkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- ObDocument2 pagesObkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- Long JohnDocument1 pageLong JohnkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- LoddlDocument1 pageLoddlkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- LolDocument1 pageLolkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- Long JohnDocument3 pagesLong JohnkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- BobbyDocument2 pagesBobbykennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- BobDocument1 pageBobkennerbobPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Drugs in Sport Info BriefDocument6 pagesDrugs in Sport Info BriefAbdul Razak MansorPas encore d'évaluation

- 100 HIIT Workouts for Fat Loss & Muscle GainDocument207 pages100 HIIT Workouts for Fat Loss & Muscle GainJostyna47% (15)

- Warm Up Weekly Goals: Week1 Week2 Week3 Week4Document3 pagesWarm Up Weekly Goals: Week1 Week2 Week3 Week4Unalyn UngriaPas encore d'évaluation

- HJ Strength Training ProgramDocument1 pageHJ Strength Training ProgramPawel MajewskiPas encore d'évaluation

- PE Physical Activity LogDocument1 pagePE Physical Activity LogLisa Melissa LakesPas encore d'évaluation

- 7X7 StrengthSolutionDocument25 pages7X7 StrengthSolutionSwarna Khare100% (5)

- Bodyweight Chaos FinishersDocument22 pagesBodyweight Chaos FinishersBoonyarit SikhonwitPas encore d'évaluation

- Kizen Sheiko 3 Day - Cycle 1Document61 pagesKizen Sheiko 3 Day - Cycle 1Dimitris OurdasPas encore d'évaluation

- P.E. 8 Module 3Document21 pagesP.E. 8 Module 3Glydel Mae Villamora - SaragenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dimkpa Chujor Ex Pres 3Document7 pagesDimkpa Chujor Ex Pres 3api-301424382Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mike O'Hearn's Power Bodybuilding - The 12-Week ProgramDocument8 pagesMike O'Hearn's Power Bodybuilding - The 12-Week Programgitocg63% (8)

- Dolan Portfolio PDFDocument6 pagesDolan Portfolio PDFJoe Yuan Julian MambuPas encore d'évaluation

- 5x5 Madcow1Document6 pages5x5 Madcow1SoteriaCastellanoMuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Definition and Type of Physical Activity and ExerciseDocument2 pagesDefinition and Type of Physical Activity and ExerciseanastitPas encore d'évaluation

- Improve Strength, Power and Reaction TimeDocument1 pageImprove Strength, Power and Reaction TimeLeRoy13Pas encore d'évaluation

- Do You Like SportDocument2 pagesDo You Like SportLinh Trịnh MỹPas encore d'évaluation

- Key To Map: Follow The F Orest CodeDocument1 pageKey To Map: Follow The F Orest CodeJoe CunninghamPas encore d'évaluation

- 21 Day Challenge V Training GuideDocument49 pages21 Day Challenge V Training GuideSharcreta Smith100% (2)

- 12-Week-Mass and Power Workout - Lee Hayward PDFDocument39 pages12-Week-Mass and Power Workout - Lee Hayward PDFdragos100% (2)

- 12 Weeks of Powerbuilding: Squat Bench Press Deadlift DAY Week 1Document15 pages12 Weeks of Powerbuilding: Squat Bench Press Deadlift DAY Week 1Wacko JackoPas encore d'évaluation

- Gorgeous Glutes Workout PlanDocument31 pagesGorgeous Glutes Workout PlanVeronica ZambranoPas encore d'évaluation

- HobbyDocument7 pagesHobbyдаріна єленюкPas encore d'évaluation

- 531 Workout TrackerDocument46 pages531 Workout Trackerandrewallen1986Pas encore d'évaluation

- B Raviraj - Sports Council - JC Selection - B RavirajDocument4 pagesB Raviraj - Sports Council - JC Selection - B RavirajTarun MeenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fitness PortfolioDocument3 pagesFitness PortfolioThomas Prince RobsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Age at Peak Performance of Successful Track and Field AthletesDocument14 pagesAge at Peak Performance of Successful Track and Field AthletesChristine BrooksPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fitness Athlete'S Guide To: Bulking For StrengthDocument11 pagesThe Fitness Athlete'S Guide To: Bulking For StrengthAnthony Dinicolantonio100% (2)

- Micro Perspectiveall in Source by Jayson C. LucenaDocument95 pagesMicro Perspectiveall in Source by Jayson C. LucenaJayson LucenaPas encore d'évaluation

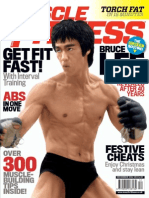

- Muscle & Fitness - December 2014 UKDocument212 pagesMuscle & Fitness - December 2014 UKVodaDan100% (1)

- Sheiko 3 Day Program - Over 80kg - 175lbsDocument14 pagesSheiko 3 Day Program - Over 80kg - 175lbsAljon S. TemploPas encore d'évaluation