Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Hoec 30 (1) - Gesamt-1

Transféré par

Be WadsworthTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Hoec 30 (1) - Gesamt-1

Transféré par

Be WadsworthDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Homo Oeconomicus Volume 30, Number 1 (2013)

ACCEDO

Accedo Verlagsgesellschaft, Mnchen

Band 82 der Schriftenreihe des Munich Institute of Integrated Studies Gesellschaft fr integrierte Studien (GIS) (Reihenkrzel 0049)

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1) www.homooeconomicus.org Cover(s): Katharina Kohl The electronic archive of Homo Oeconomicus is retrievable via www.gbi.de 2013 Accedo Verlagsgesellschaft mbH Gnesener Str. 1, D-81929 Mnchen, Germany www.accedoverlag.de, info@accedoverlag.de Fax: +49 89 929 4109 Printed and bound by Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt ISBN 978-3-89265-106-2 ISSN 0943-0180

Homo Oeconomicus Volume 30, Number 1 (2013)

Happy Bargain: Aspiring Good or Accepting Fair Deals? FRIEDEL BOLLE AND PHILIPP E. OTTO The Precautionary Principle and the Justifiability of Three Imperatives MARKO AHTEENSUU Portuguese Inquisitorial Sentencing Trends R. WARREN ANDERSON Laws and Goodness as the Foundations of Machiavellis Republic TIMO LAINE Veblen, Commons, and the Modern Corporation: Why Management Does Not Fit Economics THIBAULT LE TEXIER Comments: The Essential Relativity of Happiness and Wellbeing. Comments on Bjorn Grindes Happiness and Mental Health as Understood in a Biological Perspective, Homo Oeconomicus 29(4): 535-556. HETA ALEKSANDRA GYLLING Meanings of Happiness. Comments on Bjorn Grindes Happiness and Mental Health as Understood in a Biological Perspective, Homo Oeconomicus 29(4): 535-556. TIMO AIRAKSINEN Poem with Endnotes and References WERNER GUETH Back Issues Instructions for Contributors 1

17

37

61

79

99

105

113 119 125

HomoOeconomicus30(1):116(2013)

www.accedoverlag.de HappyBargain:AspiringGoodorAcceptingFair Deals? FriedelBolleandPhilippE.Otto*

EUVFrankfurt(Oder),Germany (eMail: bolle@europa-uni.de)

Abstract: We investigate satisfaction in bargaining, where the negotiation is followed by an individual evaluation of satisfaction and fairness levels. The strongest general determinants of satisfaction are own income and perceived fairness. Fairness perceptions again are driven by income comparisons and equality considerations (in particular equal splits), and show only a small selfserving bias. These results support the assumption that individual social utility functions are based on self-interest and fairness norms, but not (directly) on individual altruism or preferences for relative income. JEL classification: C78, I14 Keywords: Bargaining, Satisfaction Levels, Fairness Perception, Interdependent Happiness

1. Introduction Since Easterlin (1973) and Morawetz (1977) the relation between income distribution and reported happiness is increasingly investigated empirically. According to Easterlin (1995), reported happiness seems to be strongly influenced by the relative income differences in contrast to absolute income levels. Austin et al. (1980) similarly stress the importance of relative comparisons for fairness perception and fairness plus aspiration for satisfaction. But happiness or satisfaction seeking need not be a

*

Financial support by the German Science Foundation (DFG#BO747-11) is gratefully acknowledged.

2013AccedoVerlagsgesellschaft,Mnchen. ISBN9783892651062 ISSN09430180

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

constant sum game even if the sum of material payoffs is fixed. When other people around you are happy, this makes you feel happy as well (Raghunathan and Corfman 2006). One example is the relation between spouses' life satisfaction (Schimmack and Lucas 2007). If your wife/husband is happy, you tend to be happier too. Positive correlation can be expected in a partnership because of the consumption of shared goods and because of reciprocal relations. Furthermore, happiness increases productivity and bolsters against life-shocks (Oswald et al. 2009), as well as if spouses' satisfaction levels diverge the probability of divorce increases (Guven 2009). In most relationships, the distribution of consumption is determined (at least partly) by bargaining. The appropriation of non-public good household income is emphasized by Becker (1974) for whom bargaining about the distribution of the expected household income constitutes the marriage market. An unequal distribution of income and satisfaction, however, seems to destabilize partnerships or prevent establishing a partnership in the first place. Strategic advantages cannot be realized when regarded as unfair. Because of social preferences, satisfaction need not be monotonically related to the negotiated share of the pie. The most prominent example is the Dictator Game where dictators voluntarily share their income with others in experiments usually with strangers. In the most frequently investigated bargaining game, the Ultimatum Game (Gth et al. 1982), the strategic advantage is almost completely dominated by fairness requirements of the responder and resulting fear of the proposer that their offers will be rejected (van Dijk et al. 2008). Therefore, not only own income, but also procedural fairness, the resulting distribution, and perhaps the expected satisfaction of others (via empathy) will influence bargaining behavior, and thus, each of these factors partly determines experienced satisfaction. Different fairness considerations are discussed in the literature and intensively tested experimentally (for a recent overview see Bolton et al. 2008). Usually, the influential variable perceived fairness is not neutral or universal, but seems to vary with the available options (Binmore 1998). For being treated fair, people often show extensive (and economically implausible) search behavior for discounts and more strongly prefer discounts when these are a huge percentage rather than a huge amount (Kahneman and Tversky 1984; Darke and Freedman 1993). Thaler (1985) introduces the notion of transaction utility here the relation of a market price or negotiated price to a fair price, which also emphasizes the psychological value of having discounts on the initial price (Darke and Dahl 2003; Lichtenstein and Bearden 1989; Schindler 1998). The fair discount on initial prices in these studies are, however,

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

exogenous and do not result from negotiation. Moreover, fairness standards could be different with regard to culture (Berman et al. 1985), social context (Butterfield et al. 2000), involvement of friends or strangers (Boza and Diamond 1998), and further factors. The importance of aspirations for the bargaining process has been investigated by Tietz and Bartos (1983) as well as Ostmann (1992). The influence of aspiration level on the resulting satisfaction has been shown by Allen et al. (1977) for negotiated prices and post-purchase satisfaction. The strength of these different influences on the resulting evaluation remains an empirical question and it needs to be quantified which of these factors account most for changes in fairness and satisfaction. Here, we investigate determinants of satisfaction for bargaining. Satisfaction is mainly influenced by own income and perceived fairness. Perceived fairness has similar roots for everyone (social norms) and subjective components. The latter appear to indicate a (in our study small) self-serving bias which makes higher incomes for oneself appear to be fairer. Further possible influences on fairness and satisfaction ratings will be discussed in detail. 2. Bargaining Experiment The experiment is a 2x2 assignment game where four players search a partner in a one-on-one matching task with unstructured bargaining. The two workers (W1; W2) have to join one of two firms (F1; F2). Every firm can approach a worker and start bargaining, and vice versa. A match means that an agreement is made about how to distribute the joint productivities (Tables 1 and 2) between the two partners. As we always have < , F1 and in particular W1 are in a weaker strategic position than W2 and F2. Workers and firms could freely negotiate their contracts and after ten minutes the negotiation phase ended. During these ten minutes, only provisional contracts were formed, which means that further negotiations with the alternative partner were possible. A new agreement automatically canceled an earlier contract. Only the final contract determined a player's income.

W1 W2

F1

F2

Table 1: The productivities of matches

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

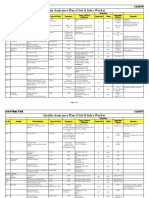

Treatment Productivities Treatment Productivities 160 460 280 400

T1 400 640 T4 460 640 160 460 280 520

T2 280 640 T5 460 640 280 520 280 460

T3 460 640 T6 400 640

Table 2: Productivities (eurocents) of matches in the six experimental treatments (rows = workers, columns = firms), with efficient matches underlined This negotiation task was repeated six times so that every subject played every treatment but mostly in different roles. In treatments T1 and T2 with productivities + < + (variables as in Table 1, values of different treatments in Table 2), in treatments T4 and T5 the inequality sign is reverted, and in treatments T3 and T6 replaced by an equal sign. Furthermore, = in T1, T3, and T5, and < in T2, T4, and T6.

Table 3: Frequencies of fairness and satisfaction ratings The six different treatments appeared in random order. In an experimental session, for every treatment eight participants were rematched into groups of four, and each time player positions were assigned randomly. At the end of a negotiation phase, participants were informed

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

about their results for this trial and had to report their experienced satisfaction" and perceived fairness" on a five point scale (from very much to very little).1 The experiment was executed under four different experimental settings. While treatments were varied in a within subjects design, settings were varied between subjects. One setting took place as a classroom experiment with face-to-face interaction (class"). Here the workers had to approach the firms, which were represented by subjects sitting at separate tables. The experimenters took care that communication was restricted to one-on-one bargaining. Neither other subjects nor the experimenter were able to follow their negotiations. Every successful match was reported in a protocol by the firm subject, including the distribution of the joint productivity. All other settings were run in the laboratory with only anonymous interaction and free offers (and possibly acceptance of offers) by workers as well as firms. One laboratory setting was implemented under the same partial information condition as the class setting (lab), i.e. players knew the productivities of the two matches in which they were involved but not the other two productivities, one with full information (info),2 and one with partial information and the possibility to fixate a contract preventing both partners from further negotiation (fix). Only in the class setting the possibility of missing answers existed, resulting in 12 missing fairness and satisfaction ratings. In the laboratory an answer had to be entered to proceed. The number of sessions, which each consisted of eight participants, was ten, except in the fix setting where only eight sessions were implemented. Altogether, 304 students of the European University Viadrina participated in the study (36.5% male, 22.6 years average age, 55.3 economics students, 71.4% German and 17.1% Polish). With six evaluations per person, this means a maximum of 1824 satisfaction as well as fairness ratings. The students were randomly recruited from a pool of students who had declared their willingness to participate in economic experiments. Most of them were first or second year students and no one had theoretical knowledge about bargaining. Further information regarding the experimental procedure, resulting incomes of the subjects,

1 The German wording is: Bitte bewerten Sie dieses Ergebnis nach (1 = niedrig; 5 = hoch), Fairness: 1 2 3 4 5; Zufriedenheit: 1 2 3 4 5. 2 In Otto and Bolle (2011) it is shown that the negotiated results do not differ with complete information. Here we will investigate whether complete information affects satisfaction.

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

and a detailed description of the bargaining results is provided in Otto and Bolle (2011). 3. Influences on Satisfaction and Fairness In the following, influential factors for the individual satisfaction and fairness ratings are analyzed. Only results with complete allocations are analyzed here, meaning all four players of the experimental market formed a match with another player. As there was a substantial amount of nomatches (23.2 percent), with only two players finding a partner and two remaining single, the number of ratings available for both satisfaction and fairness reduces to 1388. Players in the laboratory often switched to another match in the last seconds, where former partners did not have sufficient time to agree to a bargain with their alternative match partner. Late switchers might experience the feeling of guilt (or malicious pleasure) because being aware that their former partner and one more player are probable to remain single. Partial allocation also results in highly diverse payments, with two players receiving zero payoffs for this period. Therefore, their satisfaction and fairness perception can be expected to be different. Reported satisfaction and fairness of matched players with non-matched co-players are significantly lower (p < .0001 according to a one sample t-test) than for players in fully formed matches. The average rating for the group with no-matches is 2.35 for satisfaction (t(423) = -8.43) and 2.31 for fairness (t(424) = -11.83). These are fundamentally lower than for the group where all players resulted in a match with 3.15 for satisfaction (t(1388)=5.27) and 3.28 for fairness (t(1388) = 6.85). Therefore we restricted our investigation to complete matches. The correlation between a subjects satisfaction and fairness evaluation is relatively strong (0.54; p < .001) and poses the question of causality. It can be expected that the correlation is partly due to common influences and partly to a causal relation. A subject may be happy because she estimates the result to be fair or she may underlie a self-serving bias (Binmore et al. 1991; Loewenstein et al. 1992; Babcock and Loewenstein 1997) and regard bargaining results to be fairer if they provide her with more income or make her happier. As the experiments were conducted under a double blind standard the strict anonymity of decisions and evaluations is expected to prevent experimenter demand effects and other extrinsic influences on the relation of the evaluations.

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

The effects on satisfaction and fairness are further investigated in an ordered probit simultaneous equation analysis3 where a number of possible influences on the dependent variables fairness and satisfaction are taken into account. In addition to own income these are relative income measures: Rel.Income = share of the productivity in a match, es = dummy for equal split, more = max{own minus others income, 0}, less = max{others minus own income, 0}, aspmore = max{income minus aspiration level, 0}, aspless = max{aspiration level minus income, 0} others variables: others income (IncOther), satisfaction, fairness perception dummies for settings: class, lab, info, fix dummies for positions: W1, W2, F1, F2 dummies for treatments: T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6 (different productivities of matches) demographic variables: gender, age, subject of study, residence, nationality dummy for the experience of not being included in a match at the end of any previous bargaining period (NmExp).

Closeness to equal splits has turned out to be the most successful characterization of bargaining results (Otto and Bolle 2011). This is captured by es and also by more and less which are positive or negative distances to equal splits and are the decisive components of the Fehr and Schmidt (1999) utility function for inequality aversion. Aspiration level bargaining has been propagated by Tietz and Bartos (1983) and Ostmann (1992). Hypothetical aspiration levels are defined here as strategic advantages measured by the Nash bargaining solution under a simplifying assumption about outside options. When W1 and F1 negotiate the distribution of , W1s outside option is assumed to be /2, i.e., half of the productivity of a match with F2, and F1s outside option is /2. Note that Selten (1972) used this simplification in the definition of his Equal Division Core. Thus, W1s aspiration level in a negotiation with F1 is /2 + /2 - /2. Aspiration levels actually require the knowledge of the partners outside option which is provided only in the experimental setting info. As, however, results do not differ between the settings (see Otto and Bolle 2011), we may assume that this information is provided implicitly in the bargaining process.

We used the program package QLIM from SAS.

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Also, the fairness evaluation of the partner and his/her satisfaction could not be directly observed and had to be inferred from the received offers. Others variables may have effect via altruism (others income, others satisfaction) or because of a desire for common standards (fairness). The dummies for experimental and demographic differences serve mainly as control variables but may also provide additional information. We first estimated satisfaction and fairness in a seemingly unrelated ordered probit regression with all variables (see Appendix). Then we omitted all variables without significant coefficient (5% level) and estimated two hierarchical models with this reduced set of variables. In a model where fairness is affected by satisfaction the coefficient of fairness is insignificant, i.e., in our negotiations we can exclude a strong selfserving bias from own happiness. If we assume satisfaction to be influenced by fairness, the coefficient is positive and significant (p < 0.015). So we conclude that fairer results are more satisfactory.4 The pseudo R2 is small but highly significant as well as most other coefficients in Table 4. The significant Rho shows that the equations are not independent (residuals of endogenous variables are correlated). Faceto-face bargaining is apparently more satisfactory than anonymous bargaining via computer and the positive influence of income on satisfaction is plausible. It is surprising that W1 and F1, who are in a weak bargaining position, earn extra points for the latent variable which makes it more probable that they reach a higher level of satisfaction. The income equivalents of these additional values are 51 and 36 cent which means that in most cases W2 and F2 are nonetheless happier than their co-players. If in T1, W1 forms a match with F1, W2 with F2, and in both cases equal splits are negotiated, then W2 and F2 both enjoy 180 (= 320 - 140) cents more income. Our explanation for the extra happiness of W1 and F1 is that, on average, they got more than they expected from their weak bargaining position.5 This explanation is not supported, however, by a significant coefficient of aspmore. Therefore our conjecture can only be true if aspiration levels are determined non-strategically.

4 We arrive at the same conclusion if we apply this procedure with the full number of variables. After the elimination of insignificant variables we again get the same strongly significant variables (p < .001) as in Table 4.

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

Satisfaction Param. Intercept Fairness Income NmExp IncomeOth Rel.Income less es Sex German Polish W1 F1 class info T4 Limit 1 Limit2 Limit3 Limit4 Pseudo R Rho

2

Fairness Std.Err. 0.253 0.079 0.0005 0.073 0.003*** 1.509*** -0.003*** 0.673*** 0.116* 0.191* 0.162 0.0004 0.329 0.0006 0.078 0.058 0.085 0.102 Param. -0.259 Std.Err. 0.238

-1.370*** 0.192* 0.008*** 0.114

0.461*** 0.287** 0.465***

0.092 0.090 0.074 0.462*** -0.151* -0.237** 0.065 0.077 0.076 0.047 0.055 0.063

0 0.905*** 1.753*** 2.670*** 0.099 0.365***

0.056 0.079 0.105

0 0.803*** 1.634*** 2.453***

Table 4: Hierarchical ordered probit regression results for 1388 satisfaction and fairness ratings from 304 subjects in 38 independent experimental groups, with * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. The pseudo R2 is calculated according to McFadden with adjustment for degrees of freedom. Further influences on satisfaction are provided only indirectly via the fairness evaluation. It is interesting that, with the exception of the class

5

Such a dependency of happiness on aspiration levels is found by Stutzer (2004).

10

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

dummy, there are no common influences on the satisfaction and fairness ratings. Fairness is influenced by four groups of variables: others income, three variables measuring relative income, three demographic variables and three experimental variables. Note that the influences of IncOther, Rel.Income, less, and es have to be evaluated jointly.6 There is a rather small self-serving bias7 involved in the fairness ratings of the players, but it is practically impossible to offset the negative impact of leaving an equal split match in favor of higher relative income. Demographic variables are only weakly significant. Men and Germans have higher ratings than women and non-Polish foreigners. Face-to-face communication in the class setting not only improves satisfaction, but also the fairness perception. T4 may diminish the fairness ratings because of the large differences of productivities to the lowest productivity (although this difference is not much larger than in T5). The information about all match productivities (info setting) also has a slight negative influence. It is worthwhile to mention some non-significant coefficients. Satisfaction is not directly influenced by measures of relative income, and fairness not by absolute income. Neither altruistic motives (IncOther) seem to play a role in the form of direct compassion, and only prevents a strong self-serving bias in fairness rating. At last, let us make a methodological remark. In our investigation we have not considered the cluster structure of our data. Eight subjects formed an experimental group. Every subject in this group participated in six markets and interacted with every other subject in the group at least once. Testing these two cluster structures separately8 did not change our results except that standard errors are slightly larger.

If the distribution of a productivity of 400 shifts from (210, 190) to (230, 170) then the advantaged players fairness scores increase by 1.509*20/400 - 0.003*20 = 0.015 and the disadvantaged players fairness scores decrease by 0.015 + 0.003*40 = 0.135. As the width of the intervals for the transfer of latent variable scores (see limits in Table 4) into ratings is about 0.8 the probability that the advantaged player increases his rating by one category is about 1.9% and the probability that the disadvantaged player decreases his rating by one category is about 17.9%. 7 A self-serving bias may be defined as a standard that is different when applied from the viewpoints of the two bargaining partners. The (in terms of income) advantaged partner attributes higher scores to this situation than in the disadvantaged case. Bargainers do not strive to maximize fairness but, if at all, then only satisfaction. 8 SAS does not offer a random effects simultaneous equations ordered probit model and STATA allows only one cluster structure here.

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

11

4. Discussion It is not surprising that satisfaction is strongly influenced by the bargaining result (own income), but it is new that fairness is the only other important systematic determinant of satisfaction. Under the assumption that people are maximizing satisfaction, its dependence on fairness may describe social pressure. Other regarding preferences do not seem to play a decisive role. Social norms of fair behavior have a general core, but there is also some individual variability. The former is expressed by the dominant influence of equal splits and situational frames (experimental settings class and T4). The latter seems to be accompanied by a self-serving bias which is expressed by the asymmetric dependency of one's fairness perception on relative income measures. In the field of bargaining, selfserving biases concerning social norms are reported by Binmore et al. (1991) and Loewenstein et al. (1993). The influence of different positions and, thus, resulting differences in fairness perception might be more variable and ambiguous in other situations than the one considered here. Reported satisfaction and fairness can supplement investigations of bargaining behavior. Our study reveals the strong influence of fairness considerations on satisfaction and presumably on bargaining results in general. This does not directly suggest a new bargaining theory, but adds support for the inclusion of general social norms in utility functions (Cappelen et al. 2010; Krupka and Weber 2008) rather than individual empathy. Fairness perceptions, however, are only partly determined by objective norms and seem to also underlie a small self-serving bias. This bias is weaker here than might be expected from the numerous detections of such a bias. On the background of the attempts to model social behavior on the basis of an altruistic or inequity averse utility function, it is surprising that satisfaction if it is measuring utility underlies no direct influences from others income or others satisfaction, be it in absolute or relative terms. All these influences are comprised in the fairness perception. This result may stimulate research about the principle variables of social utility functions. Are these functions generally based on individual emotions (i.e., altruism, envy, a desire for revenge, etc.), or are they essentially determined by social norms? This investigation supports the latter. References Allen, B., Kahler, R., Tatham, R. and Anderson, D. (1977), Bargaining process as a determinant of postpurchase satisfaction, Journal of Applied Psychology 62, 487-492.

12

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Austin, W., McGinn, N.C. and Susmilch, C. (1980), Internal standards revisited: effects of social comparisons and expectancies on judgments of fairness and satisfaction, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 16, 426-441. Becker, G.S. (1974), A theory of marriage, in: Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital (National Bureau of Economic Research), 299-351. Berman, J., Murphy-Berman, V. and Singh, P. (1985), Cross-cultural similarities and differences in perceptions of fairness, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 16, 55-67. Binmore, K. (1998), Egalitarianism versus utilitarianism, Utilitas 10, 353-367. Binmore, K., Morgan, P., Shaked, A. and Sutton, J. (1991), Do people exploit their bargaining power? An experimental study, Games and Economic Behavior 3, 295-322. Bolton, G., Brandts, J., Katok, E., Ockenfels, A. and Zwick, R. (2008), Testing theories of other-regarding behavior: A sequence of four laboratory studies, Handbook of Experimental Economics Results 1, 488-499. Boza, M.-E. and Diamond, W. (1998), The social context of exchange: transaction utility, relationships and legitimacy, Advances in Consumer Research 25, 557-562. Butterfield, K., Trevin, L. and Weaver, G. (2000), Moral awareness in business organizations: Influences of issue-related and social context factors, Human Relations 53, 981-1018. Cappelen, A.W., Konow, J., Sorensen, E.O. and Tungodden, B. (2010), Just luck: an experimental study of risk taking and fairness, MPRA Paper 24475, University Library of Munich, Germany. Darke, P.R. and Dahl, D.W. (2003), Fairness and discounts: The subjective value of a bargain, Journal of Consumer Psychology 13, 328-338. Darke, P.R. and Freedman, J.L. (1993), Deciding whether to seek a bargain: Effects of both amount and percentage off, Journal of Applied Psychology 78, 960-965. Easterlin, R. (1973), Does money buy happiness?, Public Interest 30, 310. Easterlin, R. (1995), Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all?, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 27, 35-47. Elster, J. (1996), Rationality and the Emotions, Economic Journal 106, 1386-1397. Fehr, E. and Schmidt, K.M. (1999), A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation, Quarterly Journal of Economics 114, 817-868.

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

13

Gth, W., Schmittberger, R. and Schwarze, B. (1982), An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 3, 367-388. Guven, C. (2009), Reversing the question: Does happiness affect consumption and savings behavior?, Technical Report 219, DIW Berlin, The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1984), Choices, values, and frames, American Psychologist 39, 341-350. Krupka, E.L. and Weber, R.A. (2008), Identifying social norms using coordination games: Why does dictator game sharing vary?, IZA Paper 3860, Bonn, Germany. Lichtenstein, D.R. and Bearden, W.O. (1989), Contextual influences on perceptions of merchant-supplied reference prices, Journal of Consumer Research 16, 55-66. Loewenstein, G., Issacharoff, S., Camerer, C. and Babcock, L. (1993), Self-serving assessments of fairness and pretrial bargaining, Journal of Legal Studies 22, 135-159. Babcock, L., and Loewenstein, G. (1997). Explaining bargaining impasse: the role of self-serving biases, Journal of Economic Perspectives 11, 109-126. Morawetz, D. (1977), Income distribution and self-rated happiness: some empirical evidence, Economic Journal 87, 511-522. Oswald, A., Proto, E. and Sgroi, D. (2009), Happiness and productivity, IZA Paper 4645, Bonn, Germany. Ostmann, A. (1992), The interaction of aspiration levels and the social field in experimental bargaining, Journal of Economic Psychology 13, 233261. Otto, P.E. and Bolle, F. (2011), Matching markets with price bargaining, Experimental Economics 14, 322-348. Raghunathan, R. and Corfman, K. (2006), Is happiness shared doubled and sadness shared halved? Social inuence on enjoyment of hedonic experiences, Journal of Marketing Research 43, 386-394. Schimmack, U. and Lucas, R. (2007), Marriage matters: spousal similarity in life satisfaction, Journal of Applied Social Science Studies (Schmollers Jahrbuch) 127, 105-111. Schindler, R.M. (1998), Consequences of perceiving oneself as responsible for obtaining a discount: evidence for smart-shopper feelings, Journal of Consumer Psychology 7, 371-392. Selten, R. (1972), Equal share analysis of characteristic function experiments, in: Beitrge zur experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung (Contributions to Experimental Economics) 111, 130-165.

14

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Stutzer, A. (2004), The role of income aspirations in individual happiness, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 54, 89109. Thaler, R. (1985), Mental accounting and consumer choice, Marketing Science 4, 199-214. Tietz, R. and Bartos, O. (1983), Balancing Aspiration Levels as Fairness Principle in Negotiations, in: R. Tietz (Ed.), Aspiration Levels in Bargaining and Economic Decision Making, Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, Vol. 213, Berlin-HeidelbergNew York-Tokyo, 52-66. van Dijk, E., Kleef, G.A.v., Steinel, W. and Beest, I.v. (2008), A social functional approach to emotions in bargaining: When communicating anger pays and when it backfires, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94, 600-614. Appendix Full bivariate regression results with endogenous variables satisfaction and fairness, with standard errors in parenthesis, * p < .05, and ** p < .01. For testing the hierarchical models as fairness being based on satisfactory or vice versa, the number of variables was reduced by retaining only those variables which are significant with p < 5%. The cluster structure of the data in terms of either the individuals or the sessions does not change the significance for the 1% level.

Satisfaction Intercept Income aspmore aspless mean Rel. Income IncOther less -1.3158

(2.9615)

Fairness 2.1140

(2.9320)

0.0080**

(0.0011)

0.0009

(0.0010)

-0.0001

(0.0004)

-0.0002

(0.0004)

0.0003

(0.0004)

0.0002

(0.0004)

0.0007

(0.0146)

-0.0128

(0.0145)

0.4858

(0.6692)

1.2950*

(0.6415)

0.0004

(0.0010)

0.0028**

(0.0009)

-0.0005

(0.0008)

-0.0029**

(0.0008)

F. Bolle and P. E. Otto: Happy Bargain

15

efficient match a es satisfaction other fairness other age sex semester German Polish Frankfurt (Oder) Berlin Economics NmExp lab class info T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 W1

-0.0192

(0.4422)

0.4988

(0.4382)

-0.1320

(0.0694)

-0.1059

(0.0679)

0.1513

(0.0826)

0.6780**

(0.0837)

0.0550

(0.0308)

-0.0159

(0.0307)

-0.0101

(0.0301)

0.0241

(0.0299)

-0.0009

(0.0150)

0.0006

(0.0149)

0.0978

(0.0643)

0.1778**

(0.0639)

-0.0274

(0.0150)

-0.0229

(0.0148)

0.1028

(0.0933)

0.2248*

(0.0923)

0.0015

(0.1470)

0.3034*

(0.1460)

-0.1685

(0.1131)

-0.0159

(0.1126)

-0.2370

(0.1255)

0.1251

(0.1251)

0.0691

(0.0631)

0.0653

(0.0625)

0.1679*

(0.0789)

0.0660

(0.0779)

-0.1057

(0.0936)

-0.1679

(0.0926)

0.5544**

(0.0878)

0.4603**

(0.0871)

0.0381

(0.0972)

-0.2047*

(0.0959)

0.1094

(0.1000)

-0.0035

(0.0995)

0.1371

(0.1036)

0.0671

(0.1027)

0.0083

(0.0985)

0.0130

(0.0979)

-0.0511

(0.1084)

-0.2440*

(0.1069)

-0.0084

(0.1077)

-0.0919

(0.1065)

0.5520**

(0.1247)

0.0955

(0.1250)

16

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

W2 F1 Limit 1 Limit 2 Limit 3 Limit 4 Rho Pseudo R 2

0.0608

(0.0853)

0.0078

(0.0847)

0.4339**

(0.1188)

0.1993

(0.1188)

0

(0)

0

(0)

0.8216**

(0.0475)

0.8216**

(0.0475)

1.6651**

(0.0560)

1.6651**

(0.0560)

2.4803**

(0.0648)

2.4803**

(0.0648)

0.5460**

(0.0230)

0.104

HomoOeconomicus30(1):1736(2013)

17

www.accedoverlag.de ThePrecautionaryPrincipleandtheJustifiability ofThreeImperatives MarkoAhteensuu

UniversityofHelsinki (eMail: marko.ahteensuu@helsinki.fi)

Abstract: This paper argues for the Triad Thesis, the claim that the acceptability of the precautionary principle depends on the justifiability of three imperatives. The precautionary principle calls for early measures to avoid and mitigate serious environmental and health effects in the face of scientific uncertainty. The imperatives are as follows: First, the onus of proof should fall on risk imposers; they need to show that a proposed activity is safe enough. Second, indications of danger that do not qualify as scientific knowledge should be taken into account and may be decisive. Scientific proof is not a prerequisite for taking pre-emptive actions to mitigate risks. Third, serious and irreversible environmental and public health hazards override economic benefits related to an activity. Applying standard Cost-Benefit Analysis is misplaced. The Triad Thesis points to the need for a careful assessment of the nature and extent of justification that the three imperatives can provide. JEL codes: D81, K32 and Z18 Keywords: precautionary principle, burden of proof, standards for evidence, costbenefit analysis, normative underpinnings

1. Introduction In this paper, I will discuss how three imperatives related to the onus of proof, proof standards, and weighing costs and benefits pertain to the much-debated precautionary principle. The triad is as follows: First, the onus of proof should fall on risk imposers rather than the potentially affected parties and public authorities; they need to show that a proposed activity (such as a new experiment, technology or product) is safe enough.

2013AccedoVerlagsgesellschaft,Mnchen. ISBN9783892651062 ISSN09430180

18

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Second, scientific proof of a causal relationship between an activity and its presumed harmful effect(s) is not a prerequisite for taking pre-emptive actions to mitigate the risk. Besides available scientific results, indications of danger that do not qualify as scientific knowledge should be taken into account and may be decisive in the decision-making process. Third, serious and irreversible environmental and public health hazards override economic benefits related to an activity. Applying standard Cost-Benefit Analysis is misplaced. The precautionary principle calls for early measures to avoid and mitigate serious environmental damage and health effects in the face of uncertainty. My argument, which I call the Triad Thesis, is that the three imperatives underlie the precautionary principle. In particular, the thesis implies that the principle can be justified only if the imperatives prove right. Were they insupportable, any formulation (or specific interpretation) of the principle would unavoidably lack an adequate foundation. A crucial test to the precautionary principle lies not so much in particular criticisms levelled at it, nor in problems with its interpretation and implementation, but in the justifiability of the triad. This point has been missed in the discussions on the precautionary principle. The paper is structured in the following way: I will first highlight the double nature of the precautionary principle and then move on to consider more specifically the three imperatives and their justification. The arguments for and against each of the imperatives would warrant a booklength discussion, at the very least. My aim is not to provide a detailed overview, but to point to these discussions that have been insufficiently combined with the precautionary principle. Lastly, I will defend the Triad Thesis against possible objections and discuss its implications. 2. Double Life of the Precautionary Principle In his review on the precautionary principle, Wiener (2007: 599) suggests that it is the most prominentand perhaps the most controversial development in international environmental law in the last two decades. The precautionary principle, indeed, leads a double life. On the one hand, the principle has taken a fast track to become a fundamental principle in environmental law and policy. This can best be seen in numerous declarations and other soft law instruments that include the principle in their objectives or general principles (e.g., UNCED 1992). Many states (such as Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Sweden, and UK) have adopted the principle in their domestic environmental legislation. International treaties (e.g., CPB 2000) enshrine the principle. The precautionary principle also plays a role in case-law. It presents a

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

19

frequently cited argument in international legal disputes. The principle has been recognizedat least implicitlyin many court and tribunal decisions.1 The precautionary principle has been invoked in a wide variety of contexts. These include marine protection and disposal of hazardous wastes, fisheries management, protection of the ozone layer and chemicals regulation, conservation of the natural environment and biological diversity, climate change and global warming policies, and regulation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Besides the environmental protection, the principle is applied to public health policy. On the other hand, the precautionary principle remains a matter of an ongoing debate and controversy. Academic scholars from various disciplines (e.g., risk analysts, legal theorists, economists, political scientists, and ethicists), decision-makers, industry representatives, spokespersons for environmental organizations, and lay people continuously argue about the principle. Opponents of the principle contend that it is vague, incoherent, unscientific, and counterproductive. (I have defended the precautionary principle against common criticisms in Ahteensuu 2007; see also Sandin et al. 2002.) Proponents typically point to past regulatory failures (i.e. not taking early precautions despite early indications of danger or damage) and their devastating consequences, and to the possibility of irreversible harm to the nature. The academic debate is mainly centered on two interrelated issues. First, despite the efforts to clarify the precautionary principle and established policy documents, consensus has not been reached concerning the exact definition of the principle. Second, it is still disputed how the precautionary principle should be put into practice. There are no commonly accepted guidelines for the implementation of the principle. This even holds in the European Union (EU) where the principle has gained attention and popularity the most. In spite of the communication on the precautionary principle (CEC 2000), which was introduced by the Commission of the European Communities in order to standardize the use of the principle, the adopted national precautionary policies within the EU have varied in a wide range (see, e.g., Levidow et al. 2005). Virtually every paper on the precautionary principle stresses that there is no agreement on its right meaning or formulation and that it lacks commonly agreed-on guidelines for its implementation. (For books on the two issues, see Fisher et al. 2006; ORiordan et al. 2001; Freestone and Hey 1996; Raffensperger and Tickner 1999.)

1

Admittedly, it remains under debate whether the precautionary principle has already become a principle of customary international law (or general principles of law).

20

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

3. Taking the Normative Background Seriously In light of an ever-increasing number of analyses of the precautionary principle, one might well think that there is neither need nor room for another contribution on the subject. Academic discussion has already peaked and matured. I disagree with this, though only partially. It seems to me that many recent contributions really come close to inventing the wheel again, but the irony and basic message of the present paper is that overlooking the Triad Thesis in the discussions of the precautionary principle has resulted in reinventing the wheel(s) in these discussions. The imperatives and their justification have been extensively discussed before and independently of the precautionary principle.2 The Triad Thesis takes the normative background of the precautionary principle seriously. Thisalthough emphasized by many authorshas been lived up to by only a few in the discussion (for a review of the academic discussions, see Ahteensuu and Sandin 2012). As noted, the thesis implies that specific understandings of the principle and precautionary decisionmaking in general can be justified only if the imperatives are wellfounded. If the principle is acceptable, it is so to the extent that the three imperatives are justifiable. A related point is that the very introduction of the principle may be seen as a response to two sources of dissatisfaction: First, the prevalent risk decision-making framework in which preventative actions could be taken only after scientific proof of a risk. Second, the use of standard Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) in environmental and public health decision-making.3 Note a subtle difference between two forms of my argument. The weaker one says that the triad forms inseparable part of the precautionary principle without necessarily exhausting its whole meaning. The stronger one says that the principle is reducible to the three imperatives. There is

2 Needless to say, I do not suggest that there is no need to discuss these questions anymore. Given the foundational nature of the issues and the fact that any decision on them (i.e. adopting or rejecting the imperatives as a basis for actual policy) affects large segments of society, disagreements are probable to prevail and new ways to think about the questions are welcome. 3 These two factors do not provide a full historical account (see Ahteensuu and Sandin 2012). Recent decades of risk research and discussions have, no doubt, helped to refine and enrich the precautionary principle. There are connections between the principle and inclusive risk governance, the intricate issue of trust, and different forms of scientific uncertainty. (See, e.g., ibid.; Lemons, ShraderFrechette and Cranor 1997; see also Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993; Ravetz 2004. For an extensive discussion on the developments in risk research, see Hillerbrand et al. 2012.)

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

21

no remainder. The stronger argument might be defended given the rather unspecified nature of the imperatives, but for the purpose of this paper it is enough to settle for the weaker one. The triad plays a central role in the justification of the precautionary principle. I think that it would be difficult to argue convincingly against this. The take-home lesson: the focus should be on the three imperatives, not only on the principle. This contrasts with the common approach absorbed in the right interpretation of the principle and problems with its implementation. What we need instead or, more accurately, in addition to the common approach is a clear idea of the nature and extent of justification that the triad can offer. 3.1. Shifting the Burden of Proof on Risk Imposers The burden of proof is concerned with two interrelated questions: (1) Who is it that has to prove something? (2) What is required for that something to be shown? In risk discussions, an answer to the first question has often been framed as a choice between risk imposers on the one hand and the potentially affected parties on the other. Either it is the job of the government agencies and the general public (including the nongovernmental organizations) to show that a proposed activity is (unacceptably) risky, or the risk imposer needs to show that the activity in question is safe. Conventional wisdom has it that there has been a transition from the former to the latter. This dichotomy is, strictly speaking, a strawman. The burden does not and does not have tofall on one party alone. The issue is not who should bear the burden, but how it should be divided among the parties. In a common setting, producers need to carry out safety tests (e.g., toxicological tests for new pharmaceuticals, food additives and pesticides) and provide information on which government agencies base their risk assessment and regulatory approval. The more stringent these tests, the heavier burden is placed on risk imposers. In a sense, the very existence of an approval mechanism before placing products on the market reflects a reversal of the burden of proof by a legislator. Products are deemed (potentially) dangerous unless and until their safety is demonstrated. Another problem with the dichotomy is that total reversal of the burden of proof in the form of requests for absolute safety is untenable. The best that can be done is to (try to) show that the activity in question does not have the harmful consequences identified in scientific risk assessment (or to show that the risk can be mitigated to an acceptable level by targeted risk management measures). It is not possible to test risks that nobody knows about. We cannot rule out the possibility of harmful consequences because we do not know what we do not know (i.e. the exact scope of our

22

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

ignorance). So, for us there are no risk-free alternatives. Even if there were risk-free alternatives out there, we would not know about them because we are not able to rule out the very possibility of harmful effects.4 An answer to the second question pertaining to the burden of proof which is about proof standardstells us what needs to be shown (e.g., acceptable risk) and when the available evidence is sufficient for that. It binds the first and second imperatives underlying the precautionary principle together. The relationship between the two questions of the burden of proof is, to put it briefly, that the burden placed on the shoulders of one or the other party becomes heavier or lighter depending on the stringency of the standards for proving safety or riskiness. Imposing high proof standards for showing riskiness of an activity places the burden more on government agencies and the public. Imposing high proof standards for proving safety to a sufficient degree places the burden more on industry. (I will come back to this in more detail in the discussion of the second imperative.) Shifting the burden of proof from the risk-exposed and public authorities more onto the risk imposers may appear an unquestionably good thing. This could explain why appeals for it are often being made without paying attention to its justification. Why, then, should risk imposers bear a heavier burden of proof? The rationale is the following: Risk imposers typically gain benefits from their activities. They should be held responsible for all of the effects of these activities including externalities and risks. Risk imposers also have more resources to study and manage the risks than the public does. A protection argument says that placing the burden more on the risk imposers serves protecting public healththe present and future public and the environment. It might also be considered in terms of sensible balancing between risks and benefits: lost monetary benefits due to the situation in which a risk imposer cannot introduce an activity (because the evidential burden is not met and the following regulatory disapproval) are overweighed by the possible infringements of peoples rights and irrevocable damage to nature. Past regulatory failures have shown that the total cost of not regulating can be of a different league than the cost of something being wrongly, i.e. unnecessarily, regulated. An epistemic argument says that risk imposers may, at least sometimes, be best informed about the risks related to their activities.

Despite these problems, sustaining the crude distinction seems well-placed in contexts where there are substantial difficulties to identify and quantify complex causal networks. The effects of dumping toxic waste at sea present an example.

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

23

These arguments fall short of being conclusive. As noted above, the very framing of the issue of burden of proof has been somewhat misplaced. Furthermore, it is necessary to distinguish between the execution of the required safety tests and their payment. Even if risk imposers are responsible for the risks and they should pay the costs of the safety tests, this does not imply that they are the ones who should carry out the tests. The protection argument, in its turn, needs to be backed up by empirical evidence. Noteworthy is also that imposing strict regulation runs a risk of preventing the development of new safer technologies. What undermines the epistemic argument is that risk imposers may lack incentives to reveal fully their information on the risks. The independence of industry (funded) risk studies has been called into question. (For a more detailed discussion, see, e.g., Shrader-Frechette 1991.) 3.2. Acting before Scientific Proof and Consensus Hypothesis testing may involve two kinds of mistakes. One is accepting a hypothesis when it is, in fact, false. This amounts to concluding wrongly that there is a phenomenon or an effect. The other one is rejecting a hypothesis when it is, in fact, true. This amounts to missing an existing phenomenon or an effect. In statistical studies, the first kind of mistake takes place when one rejects the null hypothesis when it is true. The second kind of mistake takes place when one accepts the null hypothesis when it is false. These mistakes are commonly called false positives (typeI error) and false negatives (type-II error). Risk assessment, risk identification in particular, is overshadowed by analogical mistakes. A new chemical may wrongly be believed to be a carcinogen, while another might wrongly be regarded as safe. On the one hand, setting up risk assessment procedures to minimize the first kind of errors would reduce the chance of accepting false identifications of risk, i.e. false alarms, as the basis of decision-making. This involves imposing high proof standards for positing an effect and, thus, places the burden of proof more on the ones who postulate some, rather than no, severe effects. To continue the above example, weighty evidence is required before concluding that a new chemical isor, at least, should be treated as potentiallycarcinogenic. On the other hand, setting up risk assessment procedures to minimize the second kind of errors would reduce failures to identify real risks with repercussions. Causal pathways and scenarios positing indirect, delayed, cumulative and synergistic effects with little evidence in their support need to be taken seriously before concluding safety. This practice, then, places the burden more on the ones who needs to demonstrate safety, i.e. on risk imposers, rather than the general public and officialsas commonly

24

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

portrayed. Indications of danger that do not qualify as scientific knowledge suffice for treating the chemical as a (potential) carcinogen. Why, then, should measures be taken before scientific proof and consensus? An argument from history draws on the fact that waiting for scientific proof or consensus before taking preventative action has, too many times, resulted in calamities. European Environment Agencys report Late Lessons from Early Warnings: The Precautionary Principle 1896-2000 (2001) reports fourteen case studies on taking no precaution in the face of uncertainty and the serious consequences of these omissions. The crux of the matter is that scientific proof and consensus present an inadequate arbiter of regulating an activity and not regulating it. A related point is that scientific proof standards are not risk neutral, as perhaps mistakenly presumed by many. Imposing scientific purity on standards of proof and evidence, rather unintuitively, submits risk analysis to questionable assumptions of error avoidance. This is because scientific practices have been adjusted to avoiding and minimizing the first kind of errors. Accepting preliminary findings and speculative conclusions as prevailing truths in the scientific community would threaten the credibility of all subsequent research based on them. In risk assessment, the situation is different. Unwarranted allegations of risk may be costly, but missed real dangers can have devastating effects. It makes good sense to consider scenarios and causal pathways with only a little evidence on their side. In other words, it is important to pay attention and avoid the second kind of errors. Science and risk analysis, consequently, require different balance of error avoidance. If one thinks about the ultimate aims of science and risk analysis, truth and safety respectively, this conclusion becomes less surprising. The fact that both kinds of mistakes cannot be minimized at the same time makes the point even more pressing. It should be emphasized, however, that the issue is not simply whether one or the other type of mistakes should be minimized, but rather where to strike a reasonable balance. Reporting the rate of the second kind of errors is a good place to start. Although such measuresmost notably statistical powerare well-known and readily available, this is often omitted. At a theoretical level, it seems rather obvious that different proof and evidential standards apply to forming reasoned beliefs and making reasoned practical decisions under uncertainty. Applying this insight into practice is not a straightforward task. Using different proof standards in applied contexts may be taken to jeopardize scientific integrity. Restricting the use of readjusted proof standards only to the realm of applied science appears insufficient and practically impossible. As Hansson explains,

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

25

a complete reform of the standards of evidence would not only affect the interpretation of individual results in toxicology, but also our views on more basic biological phenomena. As an example, if our main concern is not to miss any possible mechanism for toxicity, then we must pay serious attention to possible metabolic pathways for which there is insufficient proof. Such considerations in turn have intricate connections with various issues in biochemistry, and ultimately we are driven to a massive reappraisal of an immense mass of empirical conclusions, hypotheses and theories (Hansson 1997: 227). Another issue is that even if one accepts that the evidential standards for environmental and public health decision-making do not coincide with the ones employed in science, one still needs to determine the level of proof that is required. Regulating activitiesi.e. restricting people and industrys choicesbased on the use of standards other than the ones employed in science may be well-founded in some cases. But it calls for an argument and any choice of the required level of proof needs to be coupled with an explanation for why it is not arbitrary. Setting a sensible limit might only be possible on a case-by-case basis in relation to the regulatory context in question. (For discussion on the reversal of the burden of proof and changing the proof standards in risk analysis, see Hansson 1997; Lemons et al. 1997.) 3.3. Against Cost-Benefit Analysis versus Trumping Economic Benefits Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA; the form Risk-Benefit-Cost Analysis, RCBA, is also employed) refers to a bunch of decision-making techniques for evaluating and comparing policies. A basic tenet of these techniques is that costs should be weighed against benefits. In order to make this possible, all the kinds of costs and benefits including those not traded on markets, such as human lives, clean air and safety at work, need to be expressed in a common denominator. A typical practice is to use dollar values assigned on the basis of willingness to pay measures. The presumption is, then, that a particular policy should not to be undertaken unless its expected total benefits outweigh the expected total costs. More generally, implemented policies should maximize the expected net benefits. CBA has widely been used in public policy, for example, in government agencies decisions whether or not to undertake environmental, safety and health regulations. CBA has been criticized on different grounds. A focal problem is the incomparability of different kinds of costs and benefits, more generally,

26

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

disvalues and values. As an example, there is no straightforward and commonly agreed-on way to weigh and balance between the disvalue of species loss and economic recession, nor between increase in mortality and faster transportation. Moreover, assigning a value to human life may be considered a doomed attempt to value the invaluable. What should be noted is that the basic problem is not about expressing benefits and costs in dollars or in any other currency, nor about assigning a monetary value on the basis of willingness to pay measures, but about an irreducibility of different kinds of disvalues and values into a onedimensional measure. Whilst the former practices have their drawbacks as pointed out by the critics, the latter presents a fundamental problem. Another issuewhich connects the third imperative with the second oneis that unproven causal relations do not count. In practice, CBA means evaluating different decision alternatives against each other by quantifying their respective outcomes and probabilities. Common forms of CBA cannot be applied to outcomes to which probability cannot be assigned. It is useful to make a distinction between two versions of the third imperative. The first one says that straightforward weighing expected costs and benefits is impossible because some possible outcomes are incomparable and/or because their probability cannot be assigned. Common criticisms against CBA provide support for this version of the imperative. The second version says that there are environmental and public health ills that trump the economic benefits related to introducing an activity. This does not mean that costs and potential unwanted consequences of regulatory measures or the option of regulatory inaction need not be considered. Indeed, they should be taken into account. It is simply that specific environmental and public health risks related to an activity weigh more than economic benefits resulting from the activity in question. It is also noteworthy that nothing is said about trade-offs between environmental risks and public health threats. Sometimes one option (proceeding with an activity) imposes the former, whilst the alternative (regulating it) introduces the latter. This is recognized in environmental health ethics discussions (see, e.g., Resnik 2012). Similarly, the imperative keeps silent about situations in which there is one environmental risk against another environmental risk as well as about situations in which there is one public health threat against another public health threat. Two finishing remarks: First, defending the latter version of the third imperative successfully is enough for the precautionary principle. Adopting this road, admittedly, results in probability-oblivious weighing. However, it is not clear whether this can be considered

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

27

problematic as the precautionary principle is typically applied exactly when the probability of the calamity is not quantifiable. Second, putting aside the problems pertaining to CBA as typically employed, its basic tenet bears compelling plausibility. Some evaluation of costs and benefits in the risk decision-making seems necessary (from the ethical point of view). It seems misguided (and unethical) not to consider the costs and benefits even if our estimates of them provide only rough guides, and however many other factors there are that determine the end result of the (ethical) appraisal. (For arguments for and against CBA, see Arrow et al. 1996; Shrader-Frechette 1985; Hansson 2007; Sunstein 2005; Kelman 1981; see also Posner 2004; Munthe 2011.) 4. The Triad Thesis in Practice The Triad Thesis says that the precautionary principle is inextricably linked with the three imperatives. In the strongest sense, the imperatives may be considered to constitute the principle. The weaker form, as noted, says that the triad plays a central role in the justification of the principle. In any case, the intimate connection is visible (to some extent) in the formulations of the precautionary principle found in environmental laws, declarations and statements. Consider the Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principle (1998) that was introduced at a conference organized by the Science and Environment Health Network (SEHN). This well-known formulation states that [w]hen an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. The paragraphs following the definition set out criteria for application of the principle. These include the following: [i]n this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public bears the burden of proof. There is no mention of balancing the environmental and health hazards against economic benefits. There are admittedly other (revisionist) formulations and interpretations of the principle to which the Triad Thesis do not seem to apply. Another well-known formulation, which was adopted at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio Janeiro, includes the qualification of cost-effective measures to prevent[ing] environmental degradation (UNCED 1992: Principle 15). In its communication on the precautionary principle, the Commission of the European Communities (2000) maintains that precautionary regulation must be based on an analysis of costs and benefits and tries to reconcile the principle with the principle of proportionality. Some authors have also tried to formulate tempered versions of the precautionary principle

28

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

compatible with CBA (for discussion, see Sunstein 2005; see also Nollkaemper 1996). The Triad Thesis can account for these kinds of formulations and interpretations in two ways. First, one of the imperatives may be further specified. Costs related to regulatory actions, such as forgone innovations (which could also have benefitted public health and the environment), and the option of regulatory inaction can be taken into account even if it is the case that some environmental and public health ills trump economic benefits. The Commissions communication, for instance, accepts the second version of the third imperative. It reads as follows: the protection of public health should undoubtedly be given greater weight than economic considerations (CEC 2000: 20). Safety margin-based understandings of the precautionary principle may be subsumed under the second imperative. Presumptions to err on the side of safety are common, for example, in fisheries management. Regulatory controls incorporate a margin of safety when they prescribe that activities should be limited below a level at which no adverse effect has been observed or predicted. Related to this is the adoption of conservative presumptions, i.e. default assumptions and methods, for calculating risks. An example from toxicology is assuming animal carcinogens to be human carcinogens too unless there is a sufficient reason not to do so. Requests for more inclusive risk assessments often linked to the precautionary principle can also be neatly dealt with specifying the second imperative. Inclusive risk assessments may consist of extending the assessments to take into consideration more complex cause-effect relationships and alternative framing assumptions, but also to include a wider peer community and even non-scientists (i.e. stakeholders and the general public). In regard to the last-mentioned, Lemons, ShraderFrechette, and Cranor suggest that a fundamental dilemma surrounding () the use of a precautionary approach is how to balance the need for expert scientific knowledge with the need to involve the public in the decisionmaking process (Lemons et al. 1997: 233; see also Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993; Ravetz 2004; Fiorino 1989; Slovic, Fischhoff and Lichtenstein 1980; Cvetkovich and Lofstedt 1999). The second strategy to account for the revisionist formulations consists of denying that the precautionary principle is present in the first place. Outlandish understandings may simply fail to represent the principle. They encapsulate something else, for example, a version of CBA. Sunstein (2005a: 383; 2005b) argues that the tempered precautionary principles are not versions of the precautionary principle, as mistakenly claimed by some authors. He calls these versions the anti-catastrophe principles supplementing CBA. Another example is as follows: When the probability of the calamity can be assigned, measures to avoid and

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

29

mitigate the possible damage fall into the scope of the prevention principle, not the precautionary principle. The close relationship between the imperatives and the precautionary principle has been noted in the relevant commentary literature. In regard to the first imperative, Van den Belt and Gremmen (2002) propose that the precautionary principle can fruitfully be reframed as a debate on the proper division of the burdens of proof. de Sadeleer (2002) discusses the issues of burden of proof at length in his Environmental Principles: From Political Slogans to Legal Rules. Presumably the most exhaustive examination of the onus of proof in legal context is by Foster (2011) in her Science and the Precautionary Principle in International Courts and Tribunals: Expert Evidence, Burden of Proof and Finality. In regard to the second imperative, Hansson (1999) argues that implementing the precautionary principle requires adjusting scientific practices, for example, by supplementing significance tests with measures of type-II errors such as the detection level. Lemons et al. (1997) maintain that there is a tension between the use of the 95% confidence rule as a normative basis to reduce speculation in scientific knowledge and the use of it as the proof standard when deciding on public policy. They also point to the fact that the moral concerns embodied by the adoption of the precautionary principle run against adopting the confidence rule. Buhl-Mortensen and Welin (1998) similarly suggest that the precautionary principle is closely connected with reducing the risk of committing type-II errors (missing real dangers in risk assessment) and that the traditional way of securing the certainty of results (the 5% rule) is in conflict with the goal of a precautionary strategy for environmental management. In regard to the third imperative, Nollkaemper (1996) discusses the cost-obliviousness of the precautionary principle. He notes that the principle has been formulated in absolutist terms in several treaties and identifies policy considerations mitigating this absolutism. Sunstein (2005a) contrasts CBA and the precautionary principle. Chauncey Starr (2003) argues that rational decision-making implies benefit/cost/risk assessment, not the precautionary principle. My suggestion is that although each of the three imperatives have been discussed in relation to the precautionary principle, their exact relation to the principlei.e. their triple role as a normative basishas been overlooked. Belt and Gremmen (2002), for example, fail to acknowledge the third imperative. In their view the principle is reducible solely to the questions of the burden of proof. As for Nollkaemper (1996), he highlights the cost-obliviousness of the principle, but pays insufficient attention to the first and second imperatives.

30

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Often one or the other imperative is discussed as a version of the precautionary principle. Wiener (2007) identifies three archetypal versions of the principle: (1) uncertainty does not justify inaction, (2) uncertainty justifies action, and (3) shifting the burden of proof. A related point nicely highlighted by Wieners classification is that the focus of the debate has been somewhat misplaced. The question is not only whether to take action in the face of scientific uncertainty, but also what action should be taken given the degree and nature of uncertainties related to the cause-effect relationships (e.g., to the probability, characterization, severity, and timing of the effects).5 Another example relates to the most common distinctionthat between strong and weak interpretations of the precautionary principle. Soule (2002) describes the strong interpretation to restrict regulators to considering environmental risk in isolation from possible benefits. There is also a total reversal of the burden of proof implying that a risk imposer needs to demonstrate a zero risk. This amounts to ascribing all the three imperatives to a specific understanding of the precautionary principle. Thinking of the precautionary principle in terms of the Triad Thesis is useful in three ways. First and most obviously, if the imperatives cannot be backed up in our socio-political or moral systems, implementing the precautionary principle unavoidably lacks adequate foundation. This cannot be fixed by simply focusing on the formulations of the principle and their implementation. Above I have outlined typical arguments for each imperative, but it should be clear by now that none of them is without problems. Two further remarks are in order: There are other arguments (not directly related to the triad) that may be thought to provide normative

5

A further complicating factoradmittedly insufficiently addressed in the present analysisis that scientific uncertainties take many forms. They result from a multitude of sources: On the one hand, some natural and social processes present high complexity. They may include non-linearities and systemic indeterminacy. On the other hand, there are different sciences with their own problem-framings and methods. Multitude of models with different assumptions (e.g., about model structures and parameter values) is being employed. There is often lack of or gaps in available data. We make extrapolations (e.g., from effects on animals to effects on humans and from higher to lower exposure or doses). There is conceptual imprecision. Consequently, in the end there may be contradictory information, results and conclusions. (For discussion on different kinds of scientific uncertainties and uncertainty categorizations, see, e.g., Ascough et al. 2008; Bedford 2001; Beven 2009; Knight 1921; Regan, Colyvan and Burgman 2002; Myhr 2010; Rowe 1994; Shrader-Frechette 1996.)

M. Ahteensuu: The Precautionary Principle

31

foundation for the precautionary principle. If these arguments do not have a bearing on the three imperatives, it is doubtful that the principle should be accepted based only on those arguments. Ethical and socio-political systems may pull to opposite directions. It is possible that the precautionary principle would be defendable ethically but not politically, or vice versa. Second, specifying the most plausible versions of each of the three imperatives bears implications for the acceptable formulation and implementation of the precautionary principle. This does not result in one correct formulation of the principle, but, at the very minimum, some of its understandings can be ruled out. Strong versions of the principle that invoke a total reversal of the burden of proof in the form of requests for an absolute proof of safety have to go. Versions that do not require any evidence for triggering the precautionary response are untenable. The same applies to the generally cost-oblivious interpretations. Defensible formulations prescribe provisional precautionary measures. Besides moratoria, these may consist of pre-market testing, labelling, and requests for additional scientific information. Some formulations of the precautionary principle include problematic phrases and needs to be revised. An obvious example of this is the use of the phrase full scientific certaintyan oxymoron. In a strict sense, a cause-effect relationship is never conclusively established by evidence. Third, the Triad Thesis ties the precautionary principle more tightly to the earlier theoretical work. It puts the principle into context. The imperatives and their justification have been discussed before and independently of the precautionary principle. Page (1978), for example, discussed early the preferable balance between the two kinds of errors in the environmental (law) context. And philosophers of science debated the issue in terms of intra- and extra-scientific values in scientific research already in the 1950s. Similarly most of the discussions about CBA and its drawbacks have been unrelated to the precautionary principle. These debates can offer valuable insight into the current dispute. Acknowledging their relevance to the precautionary principle might prevent reinventing the wheel(s) in the current discussions on the principle.6

6

Besides a top-down perspective taken in this paper, it is important to undertake bottom-up analyses of the precautionary principle. These two approaches complement each other. On the one hand, there is a need to address specific applications of the precautionary principle one by one and in relation to the regulatory context in question. I have argued elsewhere (Ahteensuu 2008) that the debate on the precautionary principle needs to be shifted from the question of whether the principleor its weak or strong interpretationis well-grounded in

32

Homo Oeconomicus 30(1)

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the three anonymous referees of Homo Oeconomicus, the managing editor Manfred Holler, and Per Sandin for their insightful comments to improve this paper. Comments on an earlier version of the paper by participants of the SORU Conference Risk and Uncertainty: Ontologies and Methods, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 23rd-25th January 2013 and the YHYS Autumn Colloquium Environmental Justice and New Metaphors, University of Turku, 22nd-23rd November 2012, were also highly appreciated. Thanks to Susanne Uusitalo for making valuable remarks on the language of this paper. This work was completed while working at the Academy of Finland Public Choice Research Centre (PCRC).

References Ahteensuu, M. (2007), Defending the Precautionary Principle against Three Criticisms, Trames: A Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 11: 366-381. Ahteensuu, M. (2008), In Dubio pro Natura? A Philosophical Analysis of the Precautionary Principle in Environmental and Health Risk Governance, Reports from the Department of Philosophy, University of Turku: Painosalama. (Electronic version at <URL: https://oa.doria.fi/handle/10024/38158>.) Ahteensuu, M. and Sandin, P. (2012), The Precautionary Principle, in R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, S. Roeser and M. Peterson (eds.), Handbook of Risk Theory: Epistemology, Decision Theory, Ethics and Social Implications of Risk, Heidelberg: Springer: 961-978.