Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1

Transféré par

Robert WhitakerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1

Transféré par

Robert WhitakerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Page 1

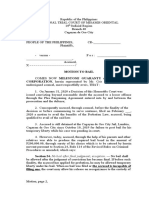

FOCUS - 2 of 5 DOCUMENTS Copyright (c) 1994 Arizona Board of Regents Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law SPRING, 1994 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1 LENGTH: 9136 words ARTICLE: SELF-DETERMINATION, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND SURVIVAL ON PLANET EARTH NAME: Louis Rene Beres * BIO:

* Ph.D., Princeton University, 1971. Professor of International Law, Department of Political Science, Purdue University.

LEXISNEXIS SUMMARY: ... Insects and fish perish in masses and individual creatures seem content to litter the earth with their corpses so long as the species can persist unaltered. ... TEXT: [*1] I. TWO SELVES: THE IRONIES OF SELF-DETERMINATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW Everywhere in the world today one hears the call for self-determination. n1 In the Middle East, in successor republics to the Soviet Union, in Africa, in southwest Asia, and most dramatically, in the former Yugoslavia, peoples and nationalities clamor for, and affirm, independence and Statehood. From the point of view of modern international law, no more valid expectation exists. n2 In the United Nations Charter n3 and in literally hundreds of other authoritative sources of [*2] world law, n4 the right of peoples and nations to self-determination is taken as a cardinal element of civilized international relations. n5 Yet, this situation is enormously ironic. By its very nature, the self-determination of peoples and nations undermines the self-determination of individuals. n6 Encouraging the expanding fragmentation of the world into [*3] competing sovereignties, this right under international law makes it nearly impossible for persons to see themselves as members of a single human family. As a result, the presumed differences between peoples are taken as critical and the essential similarities dismissed as unimportant. Not surprisingly, war n7 and genocide n8 are not only the legacy of the current century, but also the most probable planetary future. Self-determination, of course, has its place. Under the United Nations Charter, this principle is treated as an indispensable corrective to the crime of colonialism. Hence, colonial peoples are granted an "inherent" right to struggle [*4] by all necessary means, n9 and United Nations member States are instructed to render all necessary moral and material assistance to the struggle for freedom and independence. n10 Yet, the cumulative effect of claims for self-determination is violence and death. Reaffirming individual commitments to life in the "herd," these claims contradict the idea of global oneness and cosmopolis. From identification as Moslem Azerbaijanis or Christian Armenians, as Croats or Serbs, individuals all over the world surrender themselves as persons, being told again and again that meaning derives from belonging. Not surprisingly,

Page 2 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *4

these individuals are too often willing to do anything that the group commands -- even the mass killing of other human beings, as long as the victims are "outsiders." [*5] What do we really seek in world affairs? If it is authentic peace and an end to war crimes n11 and crimes against humanity, n12 then the expectation of self-determination must be balanced against the needs of planetization, of a new world order n13 in which the commonality and community of the entire human species takes precedence over the lethal calls of separatism, ethnic rivalry, and militaristic nationalism. Poised to consider that national liberation can itself be the source of armed conflict and murder, individuals everywhere must learn to affirm their significance outside the herd, as persons rather than as members. The herd is always potentially dangerous, whether it be the herd of a criminal band, a discontented nationality, or a State. n14 Before the residents of this [*6] endangered planet can discover safety in world politics, they will have to discover power and purpose within themselves. In the end, humankind will rise or fall on the strength of a new kind of loyalty, one that recognizes the contrived character of national, religious, and ethnic differences and the primacy of human solidarity. Although this kind of loyalty is certainly difficult to imagine, especially when one considers that organization into and belonging within competitive herds still offers most people a desperately needed sense of self-worth, there seems to be no alternative. Whether we seek an accommodation of Palestinians n15 and Israelis n16 in the Middle East, of Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, or of different nationalities in Eastern Europe, in the former USSR, or in the former Yugoslavia, the only real hope lies in getting those involved to see themselves as individuals. II. AFFIRMING THE INDIVIDUAL SELF: A PLANETARY IMPERATIVE [*7] To fulfill the expectations of a new global society, one that would erect effective barriers around humankind's most murderous forms of self-determination, n17 the essential initiatives must be undertaken within States. In this connection, national leaders can never be expected to initiate the essential changes on their own. Rather, the new evolutionary vanguard must -- in the fashion of the growing worldwide movement against nuclear weapons and nuclear war n18 -- grow out of informed publics throughout the world. Such a vanguard [*8] must aim to end the separation of State interests from those of its citizens and from those of humanity as a whole. This vanguard must grow out of searches for individual self-determination. But the journey from the herd to selfhood begins in myth and ends in doubt. For this journey to succeed, the individual traveling along the route must learn to substitute a system of uncertainties for what he has always believed; learn to tolerate and encourage doubt as a replacement for the comforting "securities" of Statism. Induced to live against the grain of our civilization, he must become not only conscious of his singularity, but also satisfied with it. Organically separated from "civilization," he becomes aware of the forces that undermine it, forces that offer him a last remaining chance for both meaning and survival. [*9] We may turn to Kierkegaard for guidance. Recognizing the "crowd" as "untruth," the nineteenth-century Danish philosopher warns of the dangers that lurk in submission to multitudes: A crowd in its very concept is the untruth, by reason of the fact that it renders the individual completely impenitent and irresponsible, or at least weakens his sense of responsibility by reducing it to a fraction. . . . For "crowd" is an abstraction and has not hands: but each individual has ordinarily two hands. . . . n19 And what is the most degrading crowd of all? The answer is supplied not by Kierkegaard, but by Nietzsche: The State tells lies in all the tongues of good and evil; and whatever it says it lies -- and whatever it has it has stolen. Everything about it is false. . . . All-too-many are born: for the superfluous the State was invented. n20

Page 3 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *9

In giving ourselves over completely to national self-determination, we commit a grievous form of idolatry. Allegedly offering ourselves to a "higher cause," we actually turn national frontiers into prison walls that lock up capacity for thought and authentic feeling. We nurture incessant preparations for killing by embracing the cold, metallic surfaces of the State. Without such preparations national leaders would jeopardize their positions, and the State itself would be in "danger" of relinquishing its hold on citizens as an object of libation. As Simone Weil has observed: "The State is a cold concern, which cannot inspire love, but itself kills, suppresses everything that might be loved; so one is forced to love it, because there is nothing else. That is the moral torment to which all of us today are exposed."

n21

The task, then, is for each person to become an individual. In order to reject the idolatry of militaristic nationalism and national self-determination, each man and woman must understand the lethal encroachments of the State. Recognizing in their current leadership an incapacity to surmount collective misfortune, n22 citizens must strive to produce their own private expressions of progress. "From [*10] becoming an individual no one," says Kierkegaard, "is excluded, except he who excludes himself by becoming a crowd." n23 We live in a twilight era. Faced with endless infamy of the modern State, we must understand the responsibility to be in the world, to act in history. If we are unwilling to accept abolition of the future, then we must rescue life from the threat of war and genocide. n24 But something must precede this turn of events. We must move toward meaningful definitions of selfhood by acknowledging the vulgarity of captivity involving endless cycles of useless production and consumption. Rejecting the relentless docility of the crowd, we must discard artificial definitions of wealth in favor of true private and national growth. Inventiveness must take new forms. Revolted by the mob and its mouthpieces, we begin to understand our disorder. A collapsing civilization compromises with its disease, cherishes the infectious pathogen. "The wrinkles of a nation," writes E. M. Cioran, "are as visible as those of an individual." n25 Witnessing the dying reflexes of an entire planet, we must learn to tremble at the visible manifestations of humankind's aggressions against itself. n26 After so much imposture, so much fraud, we must feel that we have had [*11] enough. Instead of being engulfed by the refined gibberish of State and society, we need to choose transformation and rebirth. The herd takes pleasure in turning the "other" into a corpse. n27 The remedy for this tragedy can never be found entirely within the realms of inter-State relations or jurisprudence. n28 It can be found only in diminishing the claims of the State herd. [*12] The problem of the omnivorous State, which subordinates all individual sensibilities to the idea of unlimited internal and external jurisdiction, was foreseen brilliantly in the 1930s by Jose Ortega y Gasset. In The Revolt of the Masses, Ortega correctly identifies the State as "the greatest danger," mustering its immense and unassailable resources "to crush beneath it any creative minority which disturbs it -- disturbs it in any order of things: in politics, in ideas, in industry." n29 Set in motion by individuals whom it has already rendered anonymous, the State positions its machinery above society so that humankind comes to live for the State, for the governmental apparatus: And as, after all, it is only a machine whose existence and maintenance depend on vital supports around it, the State, after sucking out the very marrow of society, will be left bloodless, a skeleton, dead with that rusty death of machinery, more gruesome than the death of a living organism. n30 A similar image is offered by Simone Weil: "The development of the State exhausts a country. The State eats away its moral substance, lives on it, fattens on it, until the day comes when no more nourishment can be drawn from it, and famine reduces it to a condition of lethargy." n31

Page 4 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *12

Ortega's and Weil's characterizations of the State were prefigured by Nietzsche. "State," he exclaims in the First Part of Zarathustra, "is the name of the coldest of all cold monsters. Coldly, it tells lies too and this lie crawls out of its mouth! 'I, the State, am the people.' That is a lie! It was creators who created peoples and hung a faith and a love over them: thus they served life." n32 The task, therefore, is to migrate from the Kingdom of the State to the Kingdom of the Self. But in this movement one must also want to live in the second Kingdom. This is the most difficult part of the needed migration because the Kingdom of the State has immense attractions. The risks of living within this Kingdom become apparent to most only when the possibilities of migration no longer exist. [*13] Kierkegaard understood the dilemma, and articulated it in the following way: Devoid of imagination, as the Philistine always is, he lives in a certain trivial province of experience as to how things go, what is possible, what usually occurs. . . . For philistinism thinks it is in control of possibility . . . it carries possibility around like a prisoner in the cage of the probable, and shows it off.

n33

The "trivial province of experience" must be recognized. Only then can it be indicted and condemned to speedy execution. Today this province is maintained by an endless succession of electronic and print images which distort meaning and suppress Self. Taking the lies of such images as truth, we ignore the only real truth -- the one contained and imprisoned within us. And because we live in falsehood, we are, as Simone Weil notes, "under the illusion that happiness is what is unconditionally important." n34 Furthermore, we misunderstand happiness, believing that it can be purchased, along with self-worth, by money. The connections are fractured and incoherent. Both Socrates and Plato understood that the pursuit of happiness is never the pursuit of pleasure. In fact, they are diametrically opposed. With the pursuit of pleasure, people inevitably transform freedom into obedience. Although unhindered by the normal expressions of political tyranny, they understand that becoming a self must always be treason. The State requires its members to be serviceable instruments, suppressing every glimmer of creativity and imagination in the interest of a plastic mediocrity. Even political liberty within particular States does nothing to encourage opposition to war or to genocide in other States. Since "patriotic self-sacrifice" is demanded even of "free" peoples, the expectations of inter-State competition may include war and the mass killing of other peoples. In the final analysis, war and genocide are made possible by the surrender of Self to the State. Given that the claims of international law n35 are rendered [*14] impotent by Realpolitik, this commitment to so-called power politics is itself an expression of control by the herd. Without such control, individuals could discover authentic bases of personal value inside themselves, depriving the State of its capacity to make corpses of others. The herd controls not through the vulgar fingers of politics but by the more subtle hands of Society. Living without any perceptible rewards for innerdirection, most people have discovered the meaning of all their activity in what they seek to exchange for pleasure. Hence, meaning is absorbed into the universal exchange medium, money, and anything that enlarges this medium is treated as good. According to this model, finality of life is not, as Miguel de Unamuno wrote, "to make oneself a soul," n36 but rather to justify one's "success" to the herd. Instead of seeking to structure what Simone Weil, who was strongly influenced by Unamuno, calls "an architecture within the soul," we build life upon the foundations of death. Thus does humankind nurture great misfortune. The Talmud tells us: "The dust from which the first man was made was gathered in all the corners of the world." Seizing this wisdom, people everywhere must begin to move toward generous new visions of planetary identity. Shorn of the dreadful misunderstanding that people can exist only amid the death struggles of competing herds, the residents of Earth could escape from the dark side of national self-determination n38 and recover an overriding

n37

Page 5 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *14

cosmopolitanism that brings self-affirmation and safety. [*15] III. DEATH, STATES AND IMMORTALITY: UNDERSTANDING THE CONNECTIONS What, then, must be done if each individual life, not each individual State, is to be preeminent? The answer certainly cannot be found in reason. Throughout history, the implications of correct argument have always been overcome by the most palpable nonsense. No, we must look elsewhere, beyond the rules of logical inference, into the very depths of human activity. We must look not to Plato, but to Freud, n39 not to Cicero, n40 but to Kierkegaard, to Stirner, n41 to Nietzsche, to Hesse.

n42

And we must look to Arthur Schopenhauer. This contemporary of Hegel n43 rested his philosophy upon the Kantian distinction between what is and what is rationally knowable. Seizing upon the idea that we can never know our true nature by rational inference, Schopenhauer taught that we can still be perfectly aware of it via the will, a primordial force that opposes all deliberate thought with the search for perpetual life. n44 What a mistake it would be to assume that reason governs the world. n45 Should we stand only in the tradition of Greek philosophy and Renaissance [*16] science, we would discover little to support a purposeful individual life. On the contrary, it is the utter pointlessness of individual life that is underscored by the application of reason and system to the vast panorama of life in general. Everywhere in the panorama of non-human life, nature cares only for the form or for the species. It appears wholly indifferent to the fate of individual members. Insects and fish perish in masses and individual creatures seem content to litter the earth with their corpses so long as the species can persist unaltered. Everywhere outside the human community, numberless creatures behave as if nature mocks the idea of transcendent worth for individual life. Humankind is different. Of course, the spectacle of catastrophe and annihilation has been with us from the beginning, and the seeming insignificance of individual life appears to be confirmed by every earthquake or typhoon, by every pestilence or epidemic, by every war or holocaust. Yet, each of us is unwilling to accept a fate that points not only to extinction, but also to extinction with insignificance. Where do we turn? It is to promises of immortality. And from where do we hear such promises? From religion, to be sure, but also from States that have deigned to represent God in his planetary political duties, n46 and that cry out for "self-determination." How do these States sustain the promise of immortality? One way is through the legitimization of the killing of other human beings. And why is such killing the ostensible protection of one's own life? An answer is offered by Eugene Ionesco as follows: I must kill my visible enemy, the one who is determined to take my life, to prevent him from killing me. Killing gives me a feeling of relief, because I am dimly aware that in killing him, I have killed death. My enemy's death cannot be held against me, it is no longer a source of anguish, if I killed him with the approval of society: that is the purpose of war. Killing is a way of relieving one's feelings, of warding off one's own death. n47 There are two separate but interdependent ideas here. The first is the rather pragmatic and mundane observation that killing someone who would otherwise kill you is a life-supporting action. Why assume that your intended victim would otherwise be your assassin? Because, of course, your own government has [*17] clarified precisely who is friend and who is foe. The second, far more complex idea, is that killing in general confers immunity from mortality. This idea, of death as a zero-sum commodity, is captured by Ernest Becker's paraphrase of Elias Canetti: "Each organism raises its head over a field of corpses, smiles into the sun, and declares life good." n48 Or, according to Otto

Page 6 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *17

Rank, "The death fear of the ego is lessened by the killing, the Sacrifice, of the other; through the death of the other one buys oneself free from the penalty of dying, of being killed." n49 It is time, in the Spanish philosopher Unamuno's words, "to consider our mortal destiny without flinching." n50 This, lamentably, is easier said than done because the human instinct that clings to life flees from death as the very prototype of evil, and because each singular individual is able to counter the observed fact of mortality with entire categories of exceptions. Such solipsistic boasts have been identified by George Santayana as follows: Any proud barbarian, with a tincture of transcendental philosophy, might adopt this tone. "Creatures that perish," he might say, "are and can be nothing but puppets and painted shadows in my mind. My conscious will forbids its own extinction; it scorns to level itself with its own objects and instruments. The world, which I have never known to exist without me, exists by my co-operation and consent; it can never extinguish what lends it being. The death prophetically accepted by weaklings, with such small insight and courage, I mock and altogether defy: it can never touch me." n51 Nevertheless, the fact of having been born augurs badly for immortality, and the human inclination to rebel against an apparently unbearable truth inevitably produces the very terrors from which individuals seek to escape. In its desperation to live perpetually, humankind embraces a whole cornucopia of faiths that offer life everlasting in exchange for undying loyalty. In the end, such loyalty is transferred from the faith to the State, which battles with other States in what political scientists would describe as a struggle for power, but which is often, in reality, a perceived final conflict between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness. The advantage to being on the side of the Sons of Light in such a contest is nothing less than the prospect of eternal life. n52 But the result is ongoing wars around the world. [*18] How, then, do we end these terrible wars? Most important, we must first understand them as manifestations of humankind's unwillingness to accept personal death. Death defines world politics because individuals wish to escape death. The ironies are staggering, but the connections persist and remain unexamined. IV. ACCEPTING INDIVIDUAL MORTALITY: LIBERATION OF THE ONLY TRUE SELF Once freed from their unwillingness to accept the finitude of life, individuals might finally agree upon a desacrialization of States, upon a covenant with all other individuals to treat the political as a secular realm of unalterably mundane limits. With such an agreement, the passion for "victory" would be greatly abridged, and the rationale of war between States severely impaired. Over time, every polis could become a cosmopolis, and the "realism" of power struggles between States could be revealed for what it has always been: a religious myth. But we are back at the beginning. How may we be instructed to accept our own personal mortality? Epicurus had an answer. In his Letter to Menoeceus, he counsels: Become accustomed to the belief that death is nothing to us. For all good and evil consists in sensation, but death is deprivation of sensation. And therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not because it adds to it an infinite span of time, but because it takes away the craving for immortality. n53 More than two thousand years later, Santayana settled upon similar conclusions: In endowing us with memory, nature has revealed to us a truth utterly unimaginable to the unreflective creation . . . the truth of mortality. . . . The more we reflect, the more we live in memory and idea, the more convinced and penetrated we shall be by the experience of death; yet, without our knowing it, perhaps, this very conviction and experience will have raised us, in a way, above mortality. n54 As it is memory that makes mortality an incontestable truth, says Santayana, so it is also memory that opens to us all an ideal immortality, an [*19] "immortality in representation," an opportunity to accept the knowledge of natural

Page 7 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *19

death as an occasion to "live in the spirit." Through the acceptance of death, then, each moment of life may become vastly more rich in joy, meaning and potentiality. Detached from the falsehood that existence can conquer temporality, each individual may experience an authentic notion of immortality, one that "quickens his or her numbered moments with a vision of what never dies, the truth of those moments and their inalienable values." n55 In other words, the joy and sufficiency of single moments represents the only means open to humankind for witnessing the glory of eternity. Yet, reasonable as this may be, it is a proposition not readily transmitted to an entire species. Indeed, in a world where the happy filling of a single hour is far beyond the reach of billions, it is a conclusion without much likelihood of being taken seriously. Taken by itself, the probable truth of mortality has little to do with its widespread acceptance. "Truth," as Schopenhauer notes, "cannot appear naked before the people." n56 Our persistent attachment to life does not spring from knowledge and reflection, but from the will to live. Therefore, in order to weaken this attachment in a fashion that would ultimately permit humankind to experience a new world politics, and a new form of self-determination, our will must be transformed. Only then will we be able to come to grips with the real idea of world politics and with the requirements for a durable self. As I have suggested, we hold on to life at all costs. The pathetic spectacle of jogging multitudes, punishing bodies with heat and humidity or sub-zero cold to eke out a few additional moments of life, is only the most current and visible expression of an eternal search -- the search to overcome death. Although religion springs from the need to direct this search, theological leadership is normally not at odds with the State. Indeed, today the leadership of every State speaks, with varying degrees of "success," with religious authority. The State presents itself as sacred. The idea of the State as sacred is met with horror and indignation, especially in the democratic, secular West, but this notion is indisputable. Throughout much of the contemporary world, the expectations of government are always cast in terms of religious obligation. And in those places where the peremptory claims of faith are in conflict with such expectations, it is the latter that invariably prevail. With States as the new gods, the profane has become not only permissible, it is now altogether sacred. Consider the changing place of the State in world affairs. Although it has long been observed that States must continually search for an improved power position as a practical matter, the sacralization of the State is a development of modern times. This sacralization, representing a break from the traditional [*20] political realism of Thucydides, n57 Thrasymachus n58 and Machiavelli, n59 was fully developed in Germany. From Fichte n60 and Hegel, through Ranke and von Treitschke, n61 the modern transformation of Realpolitik has led the planet to its current problematic rendezvous with self-determination. Rationalist philosophy derived the idea of national sovereignty from the notion of individual liberty, but cast in its modern, post-seventeenth century expression, the idea has normally prohibited intervention n62 and acted to oppose human dignity and human rights. n63 Left to develop on its continuous flight from reason, the legacy of unrestrained nationalism can only be endless loathing and slaughter. Ultimately, as Lewis Mumford has observed, all human energies will [*21] be placed at the disposal of a murderous "megamachine" with whose advent we will all be drawn unsparingly into a "dreadful ceremony" of worldwide sacrifice. n64 The State that commits itself to mass butchery does not intend to do evil. Rather, according to Hegel's description in the Philosophy of Right, "the State is the actuality of the ethical Idea." It commits itself to death for the sake of life, prodding killing with conviction and pure heart. A sanctified killer, the State that accepts Realpolitik generates an incessant search for victims. Though mired in blood, the search is tranquil and self-assured, born of the knowledge that the State's deeds are neither infamous nor shameful, but heroic. n65 With Hegel's characterization of the State as "the march of God in the world," John Locke's notion of a Social

Page 8 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *21

Contract -- the notion upon which the United States was founded n66 -- is fully disposed of, relegated to the ash heap of history. While the purpose of the State, for Locke, is to provide protection that is otherwise unavailable to individuals -the "preservation of their lives, liberties and States" -- for Hegel, the State stands above any private interests. It is the spirit of the State, Volksgeist, rather than of individuals, that is the presumed creator of advanced civilization. And it is in war, rather than in peace, that a State is judged to demonstrate its true worth and potential. [*22] How easily humankind still gives itself to the new gods. Promised relief from the most terrifying of possibilities -- death and disappearance -- our species regularly surrenders itself to formal structures of power and immunity. Ironically, such surrender brings about an enlargement of the very terrors that created the new gods in the first place, but we surrender nonetheless. In the words of William Reich, we lay waste to ourselves by embracing the "political plague-mongers," a necrophilous partnership that promises purity and vitality through the killing of "outsiders." Fear of death, to summarize, not only cripples life, it also creates entire fields of premature corpses. But how can we be reminded of our mortality in a productive way, a way that would point to a new and dignified polity of private selves and, significantly, to fewer untimely deaths? One answer lies in the ethics of Epicurus, an enlightened creed whose prescriptions for disciplined will are essential for international stability. The creed of Epicurus is not the caricatural hedonism so falsely associated with the philosopher, but an independence of desire and a freedom from fear -- of death especially. When, therefore, in the Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus maintains that pleasure is "the end," he says explicitly: [W]e do not mean the pleasures of profligates and those that consist in sensuality, as is supposed by some who are either ignorant or disagree with us or do not understand, but freedom from pain in the body and from trouble in the mind. For it is not continuous drinkings and revellings, nor the satisfaction of lusts, nor the enjoyment of fish and other luxuries of the wealthy table, which produce a pleasant life, but sober reasoning, searching out the motives for all choice and avoidance, and banishing mere opinions, to which are due the greatest disturbance of the spirit. n67 Sober reasoning, above all, turns our confidence towards death and our caution towards the fear of death. Aware that Socrates called such fears "bogies," Epictetus says, in Book II, Chapter I of the Discourses: What is death? A bogy. Turn it round and see what it is: you see it does not bite. The stuff of the body was bound to be parted from the airy element, either now or hereafter, as it existed apart from it before. Why then are you vexed if they are parted now? For if not parted now, they will be hereafter. Why so? That the revolution of the universe may be accomplished, for it has need of things present, things future, and things past and done with. n68 We are each "a little soul, carrying a corpse," as Marcus Aurelius says, citing Epictetus, but what sort of soul bears such a heavy burden? Is it the soul of the [*23] Platonic tradition described by Descartes as "in its nature entirely independent of the body, and in consequence that it is not liable to die with it"? n69 Such questions of metaphysics lie far beyond the purview of a political scientist -- even one who has been freed from the tyrannies of vacant empiricism -but they must be raised before we can ask the next question: How can we best liberate citizens from the "bogy" of death in order to rescue an endangered planet from nefarious definitions of self-determination? To answer such questions we need not contrast Descartes with the Epicureans, or with Spinoza, Locke or Hume. All we need to recognize is, as Santayana notes in Volume Three of The Life of Reason, that "everything moves in the midst of death." n70 Raised by this understanding "above mortality," the triumphant soul of constantly perishing bodies acknowledges that everything, everywhere, is in flux, and that even the most enduring satisfactions are not at odds with personal transience.

Page 9 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *23

But let us take leave of the metaphysical, and return to the vastly more concrete realm of international affairs. What, exactly, must be done to bring individuals to the liberation offered by Santayana? Very little, if anything! "Immortal reason," Santayana notwithstanding, will not wean our minds from mortal concerns. Perhaps, over time, humankind will envisage the eternal and detach its affections from the world of flux, but that time seems to be far in the future. For now, we must rely on something else, something far less awesome and far more mundane. We must rely on an expanding awareness that States are not the Hegelian "march of God in the world," but the vicars of annihilation and that the triumph of the herd in world politics only hastens the prospect of individual death. V. DEATH, REALPOLITIK AND PLANETIZATION: CREATING AUTHENTIC SELF-DETERMINATION This, then, is an altogether different kind of understanding. Rather than rescue humankind by freeing individuals from fear of death, this perspective recommends educating people to the truth of an incontestable relationship between death and geopolitics. By surrendering ourselves to States and to traditional views of self-determination, we encourage not immortality but premature and predictable extinction. It is a relationship that can, and must, be more widely understood. There are great ironies involved. Although the corrosive calculus of geopolitics has now made possible the deliberate killing of all life, populations all over the planet turn increasingly to States for security. It is the dreadful ingenuity of States that makes possible death in the billions, but it is in the [*24] expressions of that ingenuity that people seek safety. Indeed, as the threat of nuclear annihilation looms even after the Cold War, n71 the citizens of conflicting States reaffirm their segmented loyalties, moved by the persistent unreason that is, after all, the most indelible badge of modern humankind. As a result, increasing human uncertainty brought about by an unprecedented vulnerability to disappearance is likely to undermine rather than support the education required. Curiously, therefore, before we can implement such education, we will need to reduce the perceived threat of nuclear war n72 and enlarge the belief that the short-term goal of nuclear stability is within our grasp. To make this possible we must continue to make progress on the usual and mainstream arms control measures and on the associated strategies of international cooperation and reconciliation. In this connection, arms control [*25] obligations must fall not only on nuclear weapon States, but also upon non-nuclear States that threaten others with war or even genocide. "Death," says Norbert Elias, "is the absolute end of the person. So the greater resistance to its demythologization perhaps corresponds to the greater magnitude of danger experienced." n73 Let us, then, reduce the magnitude of danger, both experienced and anticipated. But let us also be wary of nurturing new mythologies, of planting false hopes that offer illusions of survival in a post-apocalypse world. Always desperate to grasp at promises that allay the fears of personal transience, individuals are only too anxious to accept wish-fantasies of security in the midst of preparations for Armageddon. The world is full of noise, but it is still possible to listen for real music. In the fashion of Hesse's Steppenwolf, who behind a mixture of the trumpet's chewed rubber discovers the noble outline of divine music, we may "tune out" the eternal babble of outmoded forms of self-determination to hear -- like an old master beneath a layer of dirt -- the majestic structure and full broad bowing of the strings. Caught up in a war of extermination against the individual, n74 the murdered and murderous sounds of global politics ooze on and on, but the original spirit of music can never be destroyed. Although life in the herd seeks to strip this music of its vital tones, spoiling, scratching and degrading it, for those who learn to listen, even the most ghastly of disguises gives way to beauty. Only when enough persons have learned to listen can the herds themselves be transformed. Understood in terms of international relations, this means that States themselves can become purposeful communities -- communities that sustain individuals who in turn ensure harmonious and dignified foreign policies -- but not until civic virtue has yielded to real virtue. When this happens, States themselves will be truly self-determined with genocide and inter-State conflict replaced by planetization.

Page 10 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *25

What is this planetization? It is not merely one step further along the continuum of authority transfer from civilization; it is the very opposite of civilization. It must be the very opposite! After all, Dostoyevsky reminds us of the following: And what is it in us that is mellowed by civilization? All it does, I'd say, is to develop in man a capacity to feel a greater variety of sensations. And nothing, absolutely nothing else. And through this development, man will yet learn how to enjoy bloodshed. Why, it has [*26] already happened. Have you noticed, for instance, that the most refined, bloodthirsty tyrants, compared to whom the Attilas and Stenka Razins are mere choirboys, are often exquisitely civilized? . . . Civilization has made man, if not always more bloodthirsty, at least more viciously, more horribly bloodthirsty. In the past, he saw justice in bloodshed and slaughtered without any pangs of conscience those he felt had to be slaughtered. Today, though we consider bloodshed terrible, we still practice it -- and on a much larger scale than ever before. n75 Planetization, however, provides a more productive alternative. Founded upon the requirements of the unique and fulfilled Self that is distanced from the herd, including a diminished need to "belong," planetization acknowledges that no true concern for others can appear without prior love for oneself. It is the widespread failure to understand this acknowledgment that has doomed innumerable plans for world order via some form of cosmopolis. Before we can create a global community based upon functional presumptions of singularity and oneness, self-determination in international law must be rerouted. The critical task is to determine our private Selves, not our collective selves. Legal Topics: For related research and practice materials, see the following legal topics: Criminal Law & ProcedureCriminal OffensesVehicular CrimesGeneral OverviewGovernmentsAgriculture & FoodPest & Disease ControlInternational LawSovereign States & IndividualsHuman RightsGenocide FOOTNOTES:

n1 See Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States in Accordance With the Charter of the United Nations (The Principle of Equal Rights and Self-Determination of Peoples), G.A. Res. 2625, U.N. GAOR, 25th Sess., Supp. No. 28, at 121, U.N. Doc. A/8028 (1970), reprinted in 9 I.L.M. 1292; Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, G.A. Res. 1514, U.N. GAOR, 15th Sess., Supp. No. 16, at 66, U.N. Doc. A/4684 (1960); Principles Which Should Guide Members in Determining Whether or Not an Obligation Exists to Transmit the Information Called For Under Article 73e of the Charter, G.A. Res. 1541, U.N. GAOR, 15th Sess., Supp. No. 16, at 29, U.N. Doc. A/4684 (1960).

n2 Such an expectation would have the character of a peremptory or jus cogens norm under international law. According to Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, "a peremptory norm of general international law is a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character." Even a treaty that might seek to criminalize forms of insurgency protected by this peremptory norm would be invalid. According to Article 53 of the Vienna Convention, "A treaty is void if, at the time of its conclusion, it conflicts with a peremptory norm of general international law." Convention on the Law of Treaties, (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties), opened for signature May 23, 1969, art. 53, U.N. Doc. A/CONF. 39/27, at 289, reprinted in 8 I.L.M. 679. The concept is extended to newly emerging peremptory norms by Article 64 of the Convention: "If a new peremptory norm of general international law emerges, any existing treaty which is in conflict with that norm becomes void and terminates." Id. art. 64, 8 I.L.M. at 703.

Page 11 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n3 U. N. Charter.

n4 See The Right To Self-Determination: Historical And Current Development On The Basis Of United Nations Instruments, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/Sub. 2/404/Rev. 1, (1981), a study prepared by Aureliu Cristescu, Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. See also Umozurike O. Umozurike, Self-Determination in International Law (1972) and Dov Ronen, The Quest For Self-Determination (1979).

n5 The phrase, "civilized international relations," is quite plausibly an oxymoron. Here it is instructive to consider a comment by Michel Leiris, a member of the Surrealist Group from 1924-1929: However little taste one might have for proposing metaphors as explanations, civilization may be compared without too much inexactness to the thin greenish layer -- the living magma and the odd detritus -- that forms on the surface of calm water and sometimes solidifies into a crust, until an eddy comes to break it up. All our moral practices and our polite customs, that radiantly colored cloak that hides the coarseness of our dangerous instincts, all those lovely forms of culture we are so proud of -- since it is thanks to them that we can still call ourselves "civilized" -- are ready to disappear at the slightest turbulence, to shatter at the slightest impact (like the thin mirror on a fingernail whose polish cracks or roughens), allowing our horrifying primitiveness to appear in the interstices, revealed by the fissures just as hell might be revealed by earthquakes, when the cosmic revolutions burst the fragile skin of the earth's circumference and for a moment lay bare the fire at the center, whose wicked and violent heat keeps even the stones molten. See Michel Leiris, Civilization, in Brisees: Broken Branches 19 (1989).

n6 As it is understood under international law, self-determination is a right of peoples, not of individuals. And because states, not individuals, are the traditional subjects of international law, it is upon states that the responsibility for enforcing this right must devolve. It follows that "successful" support for the principle of self-determination in particular parts of the world may take place at the expense of individual selves. This paradox was recognized and explained in the middle of the nineteenth century by Max Stirner: Liberty of the people is not my liberty! . . . A people cannot be free otherwise than at the individual's expense; for it is not the individual that is the main point in this liberty, but the people. The freer the people, the more bound the individual; the Athenian people precisely at its freest time, created ostracism, banished the atheists, poisoned the most honest thinker. See Max Stirner, The Ego and His Own: The Case of the Individual Against Authority, 214 (Steven T. Byington trans., Libertarian Book Club 1963) (1845). In its very formidable assault on authoritarianism, Stirner's book represented a "third force" -- neither a defender of the theological or monarchical state nor a protagonist of the models offered by Liberals and Socialists. Quintessentially anti-Hegel, Stirner's book strongly influenced Henrik Ibsen and called for personal insurrection rather than political revolution.

n7 For a definition of crimes against peace, or waging aggressive war, see Resolution on the Definition of Aggression, G.A. Res. 3314, U.N. GAOR, 29th Sess., Supp. No. 31, at 142, U.N. Doc. A/9631 (1975), reprinted in 13 I.L.M. 710 (1974). For pertinent codifications of the criminalization of aggression, see also U.N. Charter art. 2, para. 4; Charter of the International Military Tribunal, Annex to the Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers, Aug. 8, 1945, art. 6, 59 Stat. 1544, 82 U.N.T.S. 279; Treaty Providing for the Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy, Kellogg-Briand Pact (Pact of Paris), Aug. 27, 1928, 46 Stat. 2343, 94 U.N.T.S. 57; Declaration on the Non-use of Force in International Relations and Permanent Prohibition on the Use of Nuclear Weapons, G.A. Res. 2936, U.N. GAOR, 27th Sess., Supp. No. 30, at 5, U.N. Doc. A/8730 (1972); Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States in Accordance With the Charter of the United Nations, supra note 1; Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and Sovereignty, G.A. Res. 2131, U.N. GAOR, 20th Sess., Supp. No. 14, at 11, U.N. Doc. A/6014, (1966), reprinted in 5 I.L.M. 374 (1966); Resolution Affirming the Principles of International Law Recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal, G.A. Res. 95 (1), U.N. Doc. A/236, at 1144 (1946). See also Protocol of Amendment to the Charter of the Organization of American States (Protocol of Buenos Aires), Feb. 27, 1967, 21 U.S.T. 607, T.I.A.S. No. 6847; Charter of the Organization of African Unity, May 25, 1963, arts. II, III, 479 U.N.T.S. 39; American Treaty on Pacific Settlement (Pact of Bogota), Apr. 30, 1948, 30 U.N.T.S. 55; Charter of the Organization of American States, Apr. 30, 1948, chs. II, IV, V, 2 U.S.T. 2394, 119 U.N.T.S. 3; Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (Rio Pact), Sept. 2, 1947, 62

Page 12 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

Stat. 1681, 121 U.N.T.S. 77; Pact of the League of Arab States, Mar. 22, 1945, art. 5, 70 U.N.T.S. 237; Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (Montevideo Convention), Dec. 26, 1933, arts. 8, 10, & 11, 49 Stat. 3097, 165 L.N.T.S. 19.

n8 Genocide is a crime against humanity with precise jurisprudential meaning. It identifies as criminal any of a series of stipulated acts "committed with intent to destroy, in whole or part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group as such . . . ." Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, opened for signature Dec. 9, 1948, art. II, 78 U.N.T.S. 277, 280.

n9 The right of insurgency, of course, is affirmed in the American political tradition at the first part of the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: We hold these truths to be self-evident, That all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. The Declaration of Independence para. 2 (U.S. 1776).

n10 Although specially-constituted U.N. committees and the U.N. General Assembly have repeatedly condemned acts of international terrorism, they exempt those activities that derive from the inalienable right to self-determination and independence of all peoples under colonial and racist regimes and other forms of alien domination and the legitimacy of their struggle, in particular the struggle of national liberation movements, in accordance with the purposes and principles of the Charter and the relevant resolutions of the organs of the United Nations. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on International Terrorism, U.N. GAOR, 28th Sess., Supp. No. 28, at 1, U.N. Doc. A/9028 (1973). These exemptions regarding terrorism are corroborated by Article 7 of the General Assembly's 1974 Definition of Aggression. See Resolution on the Definition of Aggression, supra note 7. Article 7 refers to the October 24, 1970 Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States in Accordance With the Charter of the United Nations, supra note 1. For a comprehensive and authoritative inventory of sources of international law concerning the right to use force on behalf of self-determination, see The Right to Self-Determination: Historical and Current Development on the Basis of United Nations Instruments, supra note 4.

n11 Today, the laws of war, the rules of jus in bello, comprise: (1) laws on weapons; (2) laws on warfare; and (3) humanitarian rules. Codified primarily in the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and known thereby as the law of the Hague and the law of Geneva, these rules attempt to bring discrimination, proportionality, and military necessity into belligerent calculations. On the main corpus of jus in bello, see Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, done Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3114, 75 U.N.T.S. 31 (entered into force Oct. 21, 1950); Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea, done Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3217, 75 U.N.T.S. 85, (entered into force Oct. 21, 1950); Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, done Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3316, 75 U.N.T.S. 135 (entered into force Oct. 21, 1950); Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, done Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3516, 75 U.N.T.S. 287 (entered into force Oct. 21, 1950); Convention No. IV Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, with Annex of Regulations (Hague Regulations), Oct. 18, 1907, 36 Stat. 2277, 1 Bevans 631.

n12 As we will consider more closely later on, "crimes against humanity" are defined in the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, Aug. 8, 1945. See Agreement For the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers and Charter of the International Military Tribunal, supra note 7, (entered into force for the United States Sept. 10, 1945).

Page 13 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n13 Although brought into fashion by the Bush administration, the concept of "world order" as an organizing dimension of inquiry and as a normative goal of global affairs has its contemporary intellectual origins in the work of Harold Lasswell and Myres McDougal at the Yale Law School, Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn's World Peace Through World Law (1966) and the large body of writings of Richard A. Falk and Saul H. Mendlovitz. For works by this author who was an original participant in the World Law Fund's World Order Models Project, see especially Louis R. Beres and Harry R. Targ, Constructing Alternative World Futures: Reordering the Planet (1977); Planning Alternative World Futures: Values, Methods and Models (Louis R. Beres & Harry R. Targ eds., 1975); Louis R. Beres, People, States and World Order (1981); and Louis R. Beres, Reason and Realpolitik: U.S. Foreign Policy and World Order (1984).

n14 Carl Jung observed: [I]f people crowd together and form a mob, then the dynamics of the collective man are set free -- beasts or demons which lie dormant in every person till he is part of a mob. Man in the crowd is unconsciously lowered to an inferior moral and intellectual level, to that level which is always there, below the threshold of consciousness, ready to break forth as soon as it is stimulated through the formation of a crowd. See Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion, in Gloria B. Levitas, 2 The World of Psychology: Identity and Motivation 476-77 (1963).

n15 The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which seeks the formal creation of a Palestinian state, has simultaneously affirmed that such a state already exists. Significantly, at the time of the September 13, 1993 agreement with Israel, signed on the White House lawn, the PLO was clearly not acting as a state. See Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, Dec. 26, 1988, art. 1, 49 Stat. 3097, 165 L.N.T.S. 19. See the June 1990 ruling of the Southern District of New York where the PLO was a defendant in Klinghoffer v. S.N.C. Achille Lauro, 739 F. Supp. 854, 858 (S.D.N.Y. 1990). Here, in seeking favorable classification for litigation, the PLO requested the court to accept its self-description as a state. More precisely, the PLO characterized itself as "the nationhood and sovereignty of the Palestinian people." Id. at 857. The court, however, found the PLO to be an "unincorporated association." Id. at 858. It determined that the PLO lacked the key elements of statehood, as articulated by long-settled norms of international law. Id., citing National Petrochemical Co. of Iran v. M/T Stolt Sheaf, 860 F. 2d 551, 553 (2d Cir. 1988) (quoting Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States 201 (1987)), cert. denied., 489 U.S. 1081 (1989).

n16 On Israel and Jewish self-determination, see Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (Dover Publications 1988). This Dover edition is an unabridged reproduction of the work published in 1946 by the American Zionist Emergency Council, which was, in turn, based on the first English-language edition, A Jewish State, published in London, England, in 1896. The Herzl text was originally published in Vienna, in 1896, under the title Der Judenstaat. Recognizing that, "[t]he nations in whose midst Jews live are all either covertly or openly anti-Semitic," Herzl put the Jewish Question in the briefest possible form: "Are we to 'get out' now, and where to? Or, may we yet remain? And, how long?" Herzl, supra, at 86.

n17 Today, these forms include not only the "traditional" patterns of war and genocide, but also new sorts of barbarism perpetrated against the planet itself. Most dramatically, Iraq, during the recent Gulf War, resorted to deliberate environmental destruction as a way of affirming its superiority over Kuwait. The intentional dumping of millions of barrels of Kuwaiti and Saudi oil into the Persian Gulf and the torching of Kuwaiti oil wells represent clear and egregious violations of Article 53 of the Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, supra note 11. See also Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques, done Dec. 10, 1976, 31 U.S.T. 333, 16 I.L.M. 88 (entered into force Oct. 5, 1978). Regarding Saddam Hussein's "ecoterrorism" against Kuwaiti oil wells, a number of pertinent instruments pertain to marine pollution. See International Convention For the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil, done May 12, 1954, 12 U.S.T. 2989, 327 U.N.T.S. 3 (entered into force July 26, 1958). See also Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage Resulting from the Exploration and Exploitation of the Seabed Mineral Resources, done Apr. 30, 1978; Convention For the Prevention of Marine Pollution From Land Based Sources, done June 4, 1974, reprinted in 13 I.L.M. 352 (entered into force May 6, 1978); International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund For Compensation For Oil Pollution

Page 14 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

Damage, done Dec. 18, 1971, reprinted in 11 I.L.M. 284 (entered into force Oct. 16, 1978); International Convention on Civil Liability For Oil Pollution Damage, done Nov. 19, 1969, reprinted in 9 I.L.M. 45 (entered into force June 19, 1975). Still other possibly pertinent conventions are: International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution Casualties; Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollutions by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, with Annexes I and II; International Convention For the Prevention of Pollution From Ships, with Annex I; and Protocol of 1978 Relating to the International Convention For the Prevention of Pollution From Ships, with Annex.

n18 This movement is reinforced by particular conventions in force under international law. See Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles (INF Treaty), Dec. 8, 1987, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 88 Dep't State Bull. 24 (1988); Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (Helsinki Accords), Aug. 1, 1975, Dep't State Pub. No. 8826 (Genl. For. Pol. Ser. 298); Limitation on Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems Treaty Protocol, July 3, 1974, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 27 U.S.T. 1645; Joint Statement on the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (Vladivostok Agreement), Apr. 29, 1974, 70 Dep't State Bull. 677 (1974); Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests, July 12, 1974, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 71 Dep't State Bull. 217 (1974); Declaration of Basic Principles of Relations Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, May 29, 1972, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 66 Dep't State Bull. 898 (1972); Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Limitation of Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems (ABM Treaty), May 26, 1972, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 23 U.S.T. 3435, 944 U.N.T.S. 13; Interim Agreement Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Certain Measures with Respect to the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, May 26, 1972, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 23 U.S.T. 3462, 94 U.N.T.S. 3; Agreement Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Measures to Improve the U.S.-U.S.S.R. Direct Communications Link (Hot Line Modernization Agreement), Sept. 30, 1971, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 22 U.S.T. 1598, 806 U.N.T.S. 402; Agreement on Measures to Reduce the Risk of Outbreak of Nuclear War Between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (Accident Measures Agreement), Sept. 30, 1971, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 22 U.S.T. 1590, 807 U.N.T.S. 57; Treaty on the Prohibition of the Emplacement of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Seabed and the Ocean Floor and in the Subsoil Thereof (Seabed Arms Control Treaty), opened for signature Feb. 11, 1971, 23 U.S.T. 701, 955 U.N.T.S. 115; Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), opened for signature July 1, 1968, 21 U.S.T. 483, 729 U.N.T.S. 161; Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America (Treaty of Tlatelolco), Feb. 14, 1967, 634 U.N.T.S. 326; Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Outer Space Treaty), opened for signature Jan. 27, 1967, 18 U.S.T. 2410, 610 U.N.T.S. 205; Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water (Partial Test Ban Treaty), Aug. 5, 1963, 14 U.S.T. 1313, 480 U.N.T.S. 43; Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Regarding the Establishment of a Direct Communication Link (Hot Line Agreement), June 20, 1963, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 14 U.S.T. 825, 472 U.N.T.S. 163; Antarctic Treaty, Dec. 1, 1959, 12 U.S.T. 794, 402 U.N.T.S. 71; and Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the Moon Treaty), Report of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, U.N. GAOR, 34th Sess., Supp. No. 20, at 33, U.N. Doc. A/34/20 Annex II; South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone Treaty, Aug. 6, 1985, 24 I.L.M. 1440. See also Treaty on Underground Nuclear Explosions for Peaceful Purposes, May 28, 1976, U.S.-U.S.S.R., 74 Dep't State Bull. 802 (1976); and Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SALT II Treaty), June 18, 1979, S. Exec. Doc. Y, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. 37 (1979).

n19 Soren Kierkegaard, That Individual, in Existentialism From Dostoevsky to Sartre 94 (Walter A. Kaufmann ed., 1956).

n20 Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: On the New Idol, in The Portable Nietzsche 161 (Walter A. Kaufmann trans., 1954).

n21 Simone Weil, The Need For Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Toward Mankind (1952).

n22 Nietzsche reminds us that, "Often mud sits on the throne -- and often also the throne on Mud." Nietzsche, supra note 20, at 162.

Page 15 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n23 Kierkegaard, supra note 19, at 98.

n24 In making this rescue possible, we must also critically re-examine our criteria of "normalcy" in evaluations of destructive human behaviors. Our very definitions of pathological behavior now omit the most terrible crimes of unfeeling, including genocide. Using the extant definitions accepted in psychology and psychiatry, it is not necessarily pathological behavior to take part in mass murder or genocide. Thus, Eichmann and other major Nazi functionaries in the Holocaust were repeatedly described as "completely sane." What this suggests, inter alia, is the triumph of the absurd, a world in which mass killers may be "normal" but where legions of harmless people who suffer mild neuroses and anxieties are characterized as "emotionally disturbed" or "mentally ill." For an exploration of this situation, which reveals just how far-reaching the absence of responsibility of others has become in contemporary life, see Israel W. Charny, Genocide and Mass Destruction: Doing Harm to Others as a Missing Dimension in Psychopathology, Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, May 1986, at 144-57. Significantly, the perfectly "sane" genociders have often been able to transfer responsibility to others, and even to rationalize the transference in terms of legal and ethical obligations. In response to questioning at his trial in Jerusalem, Eichmann always maintained that he had not only obeyed orders (at times identifying blind obedience as the "obedience of corpses," or Kadavergehorsam), but he had also obeyed the law. Moreover, he insisted that he had lived his entire life according to the moral precepts of the philosopher Kant. In Kant's philosophy, the source of law was practical reason; for Eichmann it was the will of the Fuhrer. See Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil 137 (1963).

n25 See Emile M. Cioran, The Temptation To Exist 51 (Richard Howard ed., 1956).

n26 Understood in jurisprudential terms, these "aggressions" comprise crimes of war, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity: "crimes of war," "crimes against peace," and "crimes against humanity" are defined in the Charter of the International Military Tribunal as follows: (a) Crimes Against Peace: namely planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances, or participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the foregoing; (b) War Crimes: namely violations of the laws or customs of war. Such violations shall include, but not be limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labor or for any other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity; (c) Crimes Against Humanity: namely murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war; or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crimes within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated. See Charter of the International Military Tribunal, Annex to the Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers, supra note 7, at art. 6(a), (b), & (c).

n27 Thus, says Nietzsche, "To lure many away from the herd, for that I have come. The people and the herd shall be angry with me. Zarathustra wants to be called a robber by the shepherds." Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra's Prologue, in The Portable Nietzsche, supra note 20, at 135.

n28 These realms include the extant international law of human rights. See especially, American Convention on Human Rights, done Nov. 22, 1969, O.A.S. Treaty Series No. 36 at 1, O.A.S. OR, OEA/Ser. L/V/II., 23 Doc. 21/Rev. 6 (1979), entered into force July 18, 1978);

Page 16 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature Mar. 7, 1966, 660 U.N.T.S. 195, reprinted in 5 I.L.M. 352 (entered into force Jan. 4, 1969); Convention on the Political Rights of Women, done Mar. 31, 1953, 27 U.S.T. 1909, 193 U.N.T.S. 135 (entered into force for the United States July 7, 1976); Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, done July 28, 1951, 189 U.N.T.S. 137 (entered into force Apr. 22, 1954) (this Convention should be read in conjunction with the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, adopted by the General Assembly on Dec. 16, 1966, and entered into force, Oct. 4, 1967); European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, done Nov. 4, 1950, Europ. T.S. No. 5 (entered into force Sept. 3, 1953); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, G.A. Res. 2200, U.N. GAOR, 21st Sess., Supp. No. 16, at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1967), reprinted in 6 I.L.M. 360 (entered into force Jan. 3, 1976); International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, G.A. Res. 2200, U.N. GAOR, 21st Sess., Supp. No. 16, at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1967), reprinted in 6 I.L.M. 368 (entered into force Mar. 23, 1976); Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, G.A. Res. 1514, U.N. GAOR, 15th Sess., Supp. No. 16, at 66, U.N. Doc. A/4684 (1961); Universal Declaration Of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217, U.N. Doc. A/810, at 71 (1948). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (together with its Optional Protocol of 1976), and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights -- known collectively as the International Bill of Rights -- serve as the touchstone for the normative protection of human rights.

n29 See Jose Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses 121 (Norton 1960) (1932).

n30 Id. at 121.

n31 Simone Weil, The Need For Roots, supra note 21, at 120.

n32 Nietzsche, supra note 20, at 160.

n33 Soren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death (Walter Lowrie trans., 1954).

n34 Simone Weil, First and Last Notebooks xii (Richard Rees trans., 1970).

n35 For these claims, see Agreement For the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers and its annex, Charter of the International Military Tribunal, supra note 7. The principles of international law recognized by the charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and the judgment of the Tribunal were affirmed and adopted by the U.N. General Assembly on Dec. 11, 1946. Resolution Affirming the Principles of International Law Recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal, supra note 7. This Affirmation was followed by General Assembly Resolution 177II, adopted Nov. 21, 1947, directing the U.N. International Law Commission to "(a) Formulate the principles of international law recognized in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the judgment of the Tribunal, and (b) Prepare a draft code of offenses against the peace and security of mankind . . . ." U.N. Doc. A/519 at 112. The principles formulated are known as the Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter and Judgment of the Nuremberg Tribunal; Report of the International Law Commission, U.N. GAOR, 5th Sess., Supp. No. 12, U.N. Doc. A/1316, at 11 (1950).

Page 17 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n36 Miguel de Unamuno, The Agony of Christianity (1931).

n37 B. Sanh 38b, in The Book of Legends 14 (Hayim Nahman Bialik ed., 1992).

n38 This "dark side of national self-determination" includes terrorism. For current conventions in force concerning terrorism, see especially, European Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism, Jan. 27, 1977, Europ. T.S. 90 (entered into force Aug. 4, 1978); Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Internationally Protected Persons, Including Diplomatic Agents, adopted Dec. 14, 1973, 28 U.S.T. 1975, 13 I.L.M. 43 (entered into force for the United States Feb. 20, 1977); Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Civil Aviation (Montreal Convention), Sept. 23, 1971, 24 U.S.T. 564 (entered into force for the United States Jan. 26, 1973); Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft (Hague Convention), Dec. 16, 1970, 22 U.S.T. 1641 (entered into force for the United States Oct. 14, 1971); Convention on Offences and Certain Other Acts Committed on Board Aircraft (Tokyo Convention), Sept. 14, 1963, 20 U.S.T. 2941, 704 U.N.T.S. 219 (entered into force for the United States on Dec. 4, 1969); Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, done Apr. 18, 1961, 23 U.S.T. 3227, 500 U.N.T.S. 95 (entered into force for the United States Dec. 13, 1972). See also International Convention Against the Taking of Hostages, G.A.Res. 34/146, U.N. GAOR, 34th Sess., Supp. No. 46, at 245 (entered into force June 3, 1983; entered into force for the United States Dec. 7, 1984). On December 9, 1985, the U.N. General Assembly unanimously adopted a resolution condemning all acts of terrorism as "criminal." Never before had the General Assembly adopted such a comprehensive resolution on this question. Yet, the issue of particular acts that actually constitute terrorism was left largely unaddressed, except for acts such as hijacking, hostage-taking and attacks on internationally protected persons that were criminalized by previous custom and conventions. United Nations Resolution on Terrorism, G.A. Res. 40/61, U.N. GAOR, 40th Sess., Supp. No. 53, at 301, U.N. Doc. A/40/53 (1985).

n39 See especially, Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego 15 (James Strachey ed. & trans., 1959) (1922).

n40 Cicero's major writings, of course, are the Republic and the Laws. See De Re Publica, De Legibus, Loeb Classical Library (G.P. Putnam 1928).

n41 See Stirner, supra note 6. A formidable assault on authoritarianism in the midnineteenth century, Stirner's book represented a "third force" -- neither a defender of the theological or monarchical State, nor a supporter of models offered by Liberals and Socialists. Conceived as the rejoinder to Hegel, it argued that all freedom is essentially self-liberation -- an argument that influenced the dramatic writings of Henrik Ibsen.

n42 See especially, Hermann Hesse, Steppenwolf (Bantam Books 1963) (1927). Other representative works of Hesse are: Beneath the Wheel, Demian, Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game), and Siddhartha.

n43 See Georg W.F. Hegel, Philosophy Of Right (1821).

Page 18 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n44 See Arthur Schopenhauer, The Will To Live (Richard Taylor ed., 1962).

n45 No one, I think, has made this point more convincingly than Milan Kundera. Referring to the "drivel of propaganda," which nobody seriously believes, he describes a sheer force of violence that wills to assert itself as force: Force is naked here, as naked as in Kafka's novels. Indeed, the Court has nothing to gain from executing K., nor has the Castle from tormenting the Land-Surveyor. Why did Germany, why does Russia today want to dominate the world? To be richer? Happier? Not at all! The aggressivity of force is thoroughly disinterested; unmotivated; it wills only its own will; it is pure irrationality. Milan Kundera, The Art of the Novel 10 (Linda Asher trans., Grove Press 1988) (1986). The passage, of course, was written before the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

n46 One is reminded, in this regard, of Heinrich von Treitschke, in his published lectures on Politics, citing approvingly to Fichte: "Individual man sees in his country the realization of his earthly immortality." See Heinrich von Treitschke, Politics (Blanche Dugdale & Torben de Bille trans., 1916).

n47 This comment from Ionesco's Journal appeared in a British magazine called Encounter, May 1966. See also Eugene Ionesco, Fragments of a Journal (Grove Press 1968). Elsewhere, says Ionesco, "People kill and are killed in order to prove to themselves that life exists." See the dramatist's only novel, The Hermit 102 (1973).

n48 Ernest Becker, Escape From Evil 2 (1975).

n49 Otto Rank, Will Therapy and Truth and Reality 130 (Knopf 1945) (1936).

n50 Miguel de Unamuno, Tragic Sense of Life 43 (J.E. Crawford Flitch trans., Dover Publications 1954).

n51 George Santayana, Reason in Religion 237-38 (1982). This Dover edition is an unabridged republication of volume three of The Life of Reason, published originally by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1905.

n52 This is especially apparent in the power of Islamic fundamentalism in the contemporary Middle East.

n53 Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus, in The Stoic and Epicurean Philosophers 30 (Whitney H. Oates et al. eds. & trans., 1940).

Page 19 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

n54 Santayana, supra note 51, at 260.

n55 Id. at 260-61.

n56 Schopenhauer, supra note 44, at 8.

n57 See The Melian Debate, in Classics of International Relations 16-20 (John A. Vasquez ed., 2d ed. 1990). For complete work, see Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War (Rex Warner trans., 1954).

n58 See the argument of Thrasymachus in Plato's Republic that justice is merely "the interest of the stronger." A similar point is made by Callicles in the Gorgias, where the argument is offered that natural justice is the right of the strong man, and that legal justice is merely the barrier which the mass of weaklings establishes to save itself.

n59 See Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince (1513).

n60 See Johann G. Fichte, Addresses to the German Nation (1917).

n61 See Heinrich von Treitschke, Selections From Treitschke's Lectures on Politics 24-25 (Adam L. Gowan trans. 1914); see also John H. Randall Jr., The Making of the Modern Mind 669-70.

n62 See U.N. Charter art. 2, para. 7. See also Annex to Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States in Accordance With the Charter of the United Nations, G.A. Res. 2625, U.N. GAOR, 25th Sess., Supp. No. 28 at 122-23, U.N. Doc. A/8028 (1971); Declaration On Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States in Accordance With the Charter of the United Nations, G.A. Res. 2625, U.N. GAOR, 25th Sess., Supp. No. 28, at 121, U.N. Doc. A/8028 (1971), reprinted in 9 I.L.M. 1292 (1970); and Declaration of the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and Sovereignty, G.A. Res. 2131, U.N. GAOR, 20th Sess., U.N. Doc. A/2131/Rev. 1 (1966).

n63 As an example of the difficulties in ensuring human rights under existing international law, all major human rights treaties contain the

Page 20 11 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 1, *26

requirement to submit periodic reports to supervisory bodies. In this connection, the Centre for Human Rights in Geneva is the main organizational entity for carrying out the United Nations human rights programme. This Centre in Geneva services: The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; The International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid; The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; and The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. See United Nations Centre for Human Rights/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), Manual on Human Rights Reporting Under Six Major International Human Rights Instruments, HR/PUB/91/1 (1991). But states in violation of human rights norms are most unlikely to report unfavorably upon themselves.

n64 See Lewis Mumford, The Myth of the Machine: The Pentagon of Power (1970), a book that climaxes a series of studies by Mumford that began in 1934 with Technics and Civilization.