Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

4352494

Transféré par

Mirjana PrekovicDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

4352494

Transféré par

Mirjana PrekovicDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Breasts and Milk in Nonnus' Dionysiaca Author(s): R. F. Newbold Source: The Classical World, Vol. 94, No.

1 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 11-23 Published by: Classical Association of the Atlantic States Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4352494 . Accessed: 12/05/2013 16:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Classical Association of the Atlantic States is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical World.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

The salience of the breast theme in Nonnus' poem is obvious from the sheer number of references to it. In 21,287 hexameters there are 121 uses of gcco'q. Excluding 23 references to gulf, channel, or bay, there are 65 uses of iKct0o;, the other main word for breast, though a few of these uses clearly or possibly mean womb or lap (cf. teat, and Latin sinus).' In addition, there are 11 references to OqXiX, 82 references to (Yrepvov and atiOo; (cf. Latin pectus), of which a good many signify breast rather than chest or thorax. The product of breasts, milk, yA(x, and yXayo;, are mentioned 40 times and cognate adjectives, yaXawcto(popo;, ya Xaaio;, vsoyXay';, 11 times. Qualitatively, there are loving and detailed descriptions of the breast, an emphasis on the saving, comforting, life-giving product of the breast, as well as keen appreciation of the erotic function and appeal of breasts. Voyeurs in Nonnus focus on the breast and curse the garments that conceal them while others (seek to) touch and fondle breasts. There recur interesting ideas such as Zeus never being suckled by Rheia but by a goat, while Dionysus was suckled by his grandmother, or a daughter saving her father by her milk, or the virgin goddess Athene feeding Erechtheus. For all its cherished value, milk is destined to be rivaled, even surpassed by a new means of oral gratification, Dionysus' wine. And the breast can be not only a source of solace and salvation but also a site of power and danger. Considering the breast references as a whole gives credence to psychoanalytic theories about infantile ambivalence toward the infant's first love objects, the mother and the breast (at first not distinguished), both of which can be frustrating, "bad" objects as well as gratifying, "good" objects. Newly born infants do not have a sense of separate, individual existence. If breast-fed, they experience their mother or nurse as part of themselves. The nipple is felt to be inside and thus part of

I In the following instances K6oXto; clearly means lap or womb: Eros beats on the enclosed womb of his mother, 41.134; Eileilytheia makes a way for Beroe to exit from Aphrodite's womb, 41.162; Hermes acts as midwife to bring Beroe forth from Aphrodite's womb, 41.170; Harmonia carried in her womb the seed of many children, 5.191; first Autonoe leapt forth from her mother's fruitful womb, 5.195; Electra was one of the seven Pleiades carried in the womb of her mother, 3.333; heavenly flames delivered Dionysus struggling from his mother's burning womb, 8.397; Zeus received Dionysus after he had broken out of his mother's fiery womb, 9.1; Eileithyia did not see the birth of Dionysus from his mother's womb, 48.841; and, probably, Eros leaping from his mother's lap and taking up his bow and quiver, 33.180. Liddell, Scott, and Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon, list the following meanings for 1C6XiRo: bosom, lap, vagina; sinus genitalis, womb; cavity; fold of garment, bosom of robe; bosom-like hollow, bay, gulf. Using K6kno; to refer to the chests of men, unless the fold of an upper garment is meant, is a rather daring extension of the term. Two examples in Nonnus are: Zeus receiving the foetal Dionysus in his sweet bosom, 7.151-152, and Hermes carrying Dionysus to Ino in his lifemaintaining bosom, 9.53-54. Mao6;, Nonnus' preferred alternative to RaaO6;, can also mean any round, breast-shaped object; hill, knoll. The statistics and references for this study were gathered from W. Peek, Lexicon zu den Dionysiaka des Nonnos (Hildesheim 1975). 11

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12

R. F. NEWBOLD

the self. The breast is felt as a soft, warm cushion that blurs separateness and provides a degree of pleasure sought for the rest of life, mainly through eating and drinking.2 The power and manifold functions of the breast in Nonnus are suggested in part by the wide range of adjectives applied to iaCx6; (see n.25). Images of such a multifunctional organ suggest more than an unrestrained imagination. Rather, they suggest residues of infantile confusion and fantasy that persist into the free-floating stream of consciousness that underlies so much of the Dionysiaca. Interesting and useful analysis of infantile notions about nursing and sexuality in the Dionysiaca has been conducted by Jack Winkler.3 This study seeks to build on his work and offer further insights. The references to breasts and milk will be grouped in eight categories. 1. The breast and its milk as comforter,healer, and savior A large group of references revolve around being at the breast and being nursed. These can be subdivided into: (a) straightforward references to breastfeeding humans and animals; (b) cases when the breast has magical or extraordinary power to heal, comfort, or save; (c) cases where admission to the breast confers a special status; (d) cases where the suckling process is irregular and may be a residue of infantile confusion. (a) Breastfeeding animals and humans. These form the most numerous references and include Dionysus being brought to his aunt Ino's breast;4 Tethys feeding the Naiad Clymene (38.178-180), Electra her son and foster-child Harmonia in turn (3.394-408), Calliope Orpheus (13. 430-431), a nurse Cadmus (8.185-186), Beroe Eros (41.140-142), Agave Pentheus (46.246-248), Themis Indians (31.93-94), Themisto twin sons (3.317-318), Nicaea Iacchus (48.949-951), a virgin Bacchant a boy (45.297-303),5 a nanny a pair of kids (10.8-9), and a lioness her cubs (3.388-393).

2 See, e.g., M. Mahler, F. Pine and A. Bergman, The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant: Symbiosis and Individuation (New York 1975); M. Yalom, A History of the Breast (New York 1997) 146-52. "In Pursuit of the Nymphs: Comedy and Sex in Nonnos' Tales of Dionysos" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Texas, 1974), esp. 103-13. 4 9.95-97, 101, 107-108, 111, 39.104-105. and 5 In the case of Nicaea, who had earlier borne a child to Dionysus who now fed lacchus until he grew up, she had to express until she got the supply established, "pressing out the life-giving juice of her childnursing breasts from her teat." (Translation here and subsequently by H. Rouse, Nonnos: Dionvsiaca. 3 vols. [London 1940]). Less plausibly, the virgin Bacchant was able to establish a flow immediately when the boy, who thought she was her mother, pawed her breast: "and milky drops ran of themselves to the breasts of the unwedded maiden, she . . . offered a newly flowing teat to his childish lips; so a virgin stilled the boy with a familiar drink." A Pan, Aigicoris or Goatgluts, was so named because of his appetite for goat's milk (14.75-77) "which he pressed from nannies' udders," probably referring to milking rather than sucking.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

13

Signs of interest and emotional investment in the breast are indicated by numerous ways of describing the breastfeeding process and the behavior of mothers and nurselings. Eros sprawls over Beroe's breast and bites the teat with his gums. When Beroe feeds Eros, her breasts are "swollen with the pressure of life giving drops." Harmonia and Electra's son, Emathion, take turns at the juice from Electra's rich breast, akin to lion cubs from a lioness. Further illustrations occur below. (b) Breast as comforter, healer, or magical savior. Dionysus flees underwater from Lycurgus and takes refuge at Thetis' teeming bosom (ppuO6EvTKOQXw, 21.178-180). Hera's ambrosial milk heals Dionysus of his madness. She is told by Zeus to use her "milky dew" and "divine drops of her painhealing teat" for this purpose, the "all famous sap of (her) savior breast" (astticacicov giacoi, 35.298-305, 315-328), which will pave the way to Olympus for Dionysus. She squeezed her breast to get the milk flowing and revived him. Perhaps also belonging in this subcategory is the case of Ambrosia, a nurse of Dionysus, who, fleeing Lycurgus, prayed to mother earth, Gaia. The earth duly opened and received her in a loving bosom (qpXikyropt ixc6Xrp, 21.25-28). Similarly, when Daphne fled Apollo, mother earth opened and received her in a 33.21 1-215). compassionate bosom (oiictipgovi C6oXicw, (c) Breast as source of status or privilege. Related to the example above of Hera feeding Dionysus is Hermes' disguising himself as Hera's son Ares and sucking milk from her breast (9.232-234). He thus became her foster-son and so disabled her from attacking him; by contrast, Hera continued to persecute Dionysus. Heracles likewise drank the immortal milk of Hera (40.421). Rheia's suckling of her grandson Dionysus was highly honorific and something she did not do for Hera's son, as Semele triumphantly reminds Hera.6 Semele here says that Dionysus sucked at the same breast as Zeus had done but elsewhere Pentheus doubts Dionysus' claim and says that not even Zeus enjoyed that privilege, sucking on the goat Amalthaea instead (46.12-17: cf. 28.314-316). Not quite correctly, Semele adds that Dionysus does not need Hera's milk for he has milked a nobler breast and for that reason will dwell in the heavens (9.237-242). Beroe, the founder of the city later renowned for its jurisprudence, received from the prudent (`RppOVt) breast of her foster mother Astraea not only milk but also streams of laws, so that the infant babbled legal phrases (41.212-215).

6 9.224-225. There is a more allusive reference at 9.152-153, where Hermes delivers Dionysus to Rheia and declares that the mother of Zeus should be the foster-mother (Roala) and nurse (trtOivq) of her grandson. 1.21 has Dionysus stealing in an underhand way (roickinrrov?a) the milk of the Xeovtookoto (lion-keeping or lion-feeding) goddess. The context suggests he changed his form to that of a lion to do this, so lion-feeding may be the better translation. Throughout the poem there are elements of rivalry and triumph in gaining access to the breast.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14

R. F. NEWBOLD

(d) Irregularities. The Dionysiaca projects a multinippled cosmos, the ideal, perhaps, of the insatiable infant, and it celebrates a god of growth, fertility, and ubiquitous oral solace. It should not be surprising therefore if milk-laden teats become available in circumstances we do not normally expect. Apart from Rheia suckling lions (see n.6) and a goat suckling Zeus, a panther nurses the twin sons of Dionysus and Aura "with intelligent (aoqo) breast" (48.913) and Bacchants nurse lion cubs (14.361-362, 24.129-130). Occasionally in real life a woman who has never been pregnant can, usually with difficulty however, establish a flow of milk. This may not be a problem for goddesses, and there are four references to virgin Athene nursing the motherless Erechtheus at her manly (apaEvt) breast.7 She also received Iacchus to her maiden breast and "let the alien (voOov) milk trickle of itself from the unripe breast" (48.954-957). Artemis, albeit tauntingly, urges Aura, a "virgin mother," to give her breast to her sons (48.858-859). Astraea, nurse of Beroe, and of the whole cosmos, is a parthenos who feeds with virgin (70ap0Eviq) milk (41.214-216) and is presumably one of those Great Mother figures who are fecund but unattached to any one man.8 In another unusual situation, Tectaphus' life is saved by the milk of his daughter Eerie, whose marital status is not given but whose devotion is enthusiastically commemorated (26.100-142). When he is later killed in battle, Eerie's laments recall her once salutary milk and she addresses him both as son and as father (30.167-185). In a striking image that relates not only to examples above but to examples below, the sun, Helios, brings forth the motherless moon in childbirth. Selene receives her light by milking (a'[tFXyt?at) him (40.375-377). Aura can wish that her tormentor Artemis bear a child and "trickle woman's milk from (her) man's breast" (48.806-807). For Nonnus, male nipples can at least offer comfort, if not milk (it is not entirely clear) to a child, Palaemon, who, in the absence of his mother Ino "cried for the milky teat." His father Athamas' breast (1aio6q) removed the yearning for the mother (9.307-31 1). But on the island of the Graioi men actually lactate, for there children suck on the manly breast of a milk-bearing (yaXcxco(p6pou) father and "steal (17i0o1CXErToVTE;, perhaps conveying not just irregularity but impropriety) their drink (E?pcev, literally "dew") with pouting lips in place of the usual mother" (26.52-54). The above references to the role of manly breasts (of Athene, Artemis, Athamas, the Graioi) and the role of Helios vis-A-vis Selene suggest a certain fluidity and possibly residues of infantile confusion about gender differences.

7 13.173-179: cf. 27.1 12-119, 322-323, 48.956. Nonnus emphasizes the irregularity of the nurture: "Bright eyes unwedded turned nursemaid, and shamefast clasped with her inexperienced maiden arm that son of Hephaestus" (13.175177), "she the virgin enemy of wedlock" (27.114). x For discussion of Great Mother parthenoi, see R. McCully, "Qualities Associated with the Ruling Goddesses of the Ancient World," Journal of Ps-'choanalYtic Anthropology 9 (1986) 1-18.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

15

2. Breasts as sources of dangerous or aggressive power. In a dream about his forthcoming confrontation with Lycurgus, Dionysus sees lightning flash from the bosom of the sky (ci0epioto ic6oXkou)to blind the lion that represents the brutal tyrant (18.193195). Zeus passed from the bosom of the sky flashing the lightning that was about to consume Semele (8.368-372). The image here may gain appropriateness from and foreshadow the "breast wars" of book 48 (see below, category 3) and the earlier reference to Semele's naked breasts "armed against Cronides, volleying shafts of love" (7.263-264). The breast of Aphrodite shoots forth something greater than a spear (ikteov FSyxso;) against the Indian warrior Morrheus that makes him soft like a lady's groom (35.173-174). For the giant Damasen, brought forth from Gaia parthenogenetically, spears served as a nourishing breast (25.489-490).9 One of the most extraordinary of the many remarkable images in Nonnus occurs at 35.205-222:

Morrheus . . . stretched out a daring hand towards the modest girl (the Bacchant Chalcomede) and caught the chaste maiden's inviolate dress. And now he would have seized her . . . and ravished the maiden votary in the flame of a bridegroom's desire; but a serpent darted out of her immaculate bosom to protect the virgin maid, and curled about her waist guarding her body all round with its belly's coils. . . . The coiled defender terrified the man of war; he curled his tail round the man's neck in twisted coils, with his wild mouth for a lance, and many a snaky shaft came darting poison against him, some darting through her uncoifed hair, some from her snake-protected loins (8paicovtoOc6koto iR)oq), some from her breast, wild warriors hissing death.

It is difficult to avoid the concept of the powerful phallic woman here, with the phallus magically residing at either or both seats of power, the breast and the genitals, a concept that is the product of the primary thought processes of infantile fantasy, indifferent to logic and contradiction.'0 Both penis and breast have erectile capacity, produce a powerful creamy substance, and can be a source of pride and anxiety to their owner." The idea of shafts from the breast having a phallic significance, only implicit in the above examples involving Semele and Aphrodite, is made more explicit by Chalcomede's case and by an example earlier in the poem where an Indian warrior, having slain a Bacchant, is powerfully attracted to her corpse. The wounder becomes the wounded, and he vacillates between fear and lust (35.21-78). Addressing the naked girl, he likens her breast (aticOoq) to a bow, since her breasts surpass the

9 25.489-490. It is not clear how metaphorical this notion is, whether the spears are maternal nipples or analogous to them. '? See M. Klein, Developments in Psychoanalysis (London 1952) " The equation of semen and milk is common. Breast milk can be some distance and be considered "better" than that produced by others. Friedman, "Mother's Milk: A Psychoanalyst Looks at Breastfeeding," analytic Study of the Child 51 (1997) 475-90. that is, 163-74. squirted See M. Psycho-

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16

R. F. NEWBOLD

"archersof the Loves" (<ateitfjpe; 'Ep6nowv, 35.42-43). This comment gains added significance from Nonnus' earlier observation that the Bacchant's naked thighs were armed in the same way against her attacker (F0)p1X0i1aav: this word is used of Semele's breasts at 7.264 as they shoot shafts of love), with "archers of the Loves" (35.25-26). The fantasy link between breasts and genitals also occurs at 14.363-364, where a Bacchant "coiled a serpent thrice round her breast unharmed . . . while it gazed at her thigh so close" (7ye'rovt gup4, literally "neighboring thigh"). One does not normally think of the thigh as being proximate to the breast even if it here signifies the groin, as it does at 30.218.2 There is, however, another way of regarding the above passages. Equation of breast and face, nipple and eye, is culturally widespread, and the shafts that emanate from the eye/breast could originate in the hostility of the infant projected onto the mother. Typically, the infant focuses upon the eyes of the mother while sucking. Such projection may be the origin of belief in the Evil Eye.'3 3. Breasts as erotic and critically appraised objects. When Aphrodite disguises herself as a maid of Harmonia, she says to Harmonia of Cadmus (whom she wants Harmonia to marry), "I could gladly die if he would only slip a willing hand into the orb of my bosom and, pressing my two breasts . . . delight me with brushing kisses" (4.147-151). Zeus touched with love-crazed hands the hitherto untouched breasts of lo (3.284-286) and, loosening the bodice around Europa's bosom, pressed as if unwillingly "the swelling circle of the firm breast" (1.347-348). Disguised as a serpent, he slipped into her bosom, wrapped himself around her breasts and poured on her (or just her bosom) honey rather than the deadly poison of a viper.'4 A satyr laid chary fingers upon a Bacchant's

12 The fantasy of proximity and kinship between breast and thigh/groin has a physiological basis. Lactating women sometimes notice a flow of milk during coitus, and breastfeeding can induce pelvic contractions similar to those accompanying orgasm. The pelvic contractions and erotic sensations that may visit a mother during breastfeeding often lead to feelings of disgust and loathing toward the infant that excites them, and to withholding or other hostile behavior that gives the infant grounds for sensing a hostile mother and breast. See W. Lederer, The Fear of Women (New York 1968) 241, and C. Sarlin, "The Role of Breast-feeding in Psychosexual Development," Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 29 (1981) 631-41. 13 Evidence is supplied by R. Almansi, "The Face-Breast Equation," Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 8 (1960), 43-70. Cf. M. DeForest, "Clytemnestra's Breast and the Evil Eye," 129-48, in M. DeForest, ed., Woman's Power, Man's Game (Wauconda, III., 1993), on the combination of nourishing breast and evil eye in Aeschylus' Choephoroi. For toxicity and the breast, see n.14, below, and the numbing of Dionysus' hand when he touched Beroe's breast (42.69-70). 1' 7.330-333. The association of serpent and breast is again notable. In this case, Semele (or her breast) is disarmed with honey rather than armed or harmed with poison.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

17

bosom and pressed her breast (12.390-393). The oxherd Hymnus, lusting after the huntress Nicaea, wishes he could be the bowstring pressed to her breast (15.260-261). As if in a trance, Dionysus "brought a longing hand near her (Beroe's) breast, and stroked her belt as if not thinking what he did" (42.67-69). With the possible exception of Zeus and o,"5 the touching of the breasts in all the above instances occurs in the imagination, indirectly, timidly, perfunctorily, or when disguised. Such approaches may have something to do with erotic technique since desire and hesitation are both absent when Harmonia tearfully kissed in farewell her fostermother's breast (and hand, eyes, feet, and head, 4.199-201). And corpses do not enjoin restraint. Thus, the Indian warrior boldly "handled often the swelling rosy breast even now like an apple" of the slain Bacchant (35.33-34). In other references to the erotic appeal of breasts it is the visual pleasure they offer to the safely distanced viewer that is stressed.'6 Hymnus enjoys the sight of the fingers of Nicaea drawing back the bowstring close to her rosy right breast (15.331-334). The sight of even the covered breast can awake fevered imaginings, notably when Dionysus curses the bodice that deprives him of a view of Beroe's breasts. "Glancing from side to side (i.e., from one breast to the other) he saw the shining skin of her breasts as if naked" (42.451-453). By contrast, when he touched her breast, his hand grew numb (v6p1 cE), as if he had touched something toxic (42.69-70). The covered breast could be erotic because the viewer could safely identify with the "modest, caoappova," bodice "which held her breast so tight" (Zeus ogling Persephone, 6.605). Typhon's delight in Cadmus' pipe playing is compared to a youth who notes "the circle of the blushing breast pressed by the bodice" (1.529530). Morrheus' pleasure in the appearance of Chalcomede is highlighted by the teasing sight of "the delicate round of her breast stretching the (diaphanous) robe from within."'7 As we have seen, the erotic aspects of breasts can attract the poet's observation on whether they are veiled or exposed. At times it does not matter much to the panting desire of the ogler. To

'5 But even here there is evasion and indirectness. Zeus touched the breasts of the Inachian heifer, or, as Rouse puts it, "the heifer child of Inachus." On the often distanced mode of sexuality in the Dionysiaca, see G. Braden, "Nonnos' Typhoon: Dionysiaca Books I and II," Texas Studies in Language and Literature 15 (1974) 851-79, esp. 873-74. There is a deep fear of sex in Nonnus' poem. See R. Newbold, "Fear of Sex in Nonnus' Dionysiaca," Electronic Antiquity 4.2 (April 1998) 1-15. 6 When Boreas, jealous of Zeus abducting Europa, whistles on or at the unripe breasts of the girl (1.69-71), is it the visual appeal (irea{ptcav) or the delicate airy touch that is emphasized? Consistent with the rest of Greek literature there is no reference in Nonnus to breasts manifesting erotic arousal on the part of women. See D. Gerber, "The Female Breast in Greek Erotic Literature," Arethusa 11 (1978) 203-12. 17 14.277-280: cf. 30.317. Outside Nonnus, not a common motif in literary breast erotica, it seems. See Gerber (above, n.16) 205.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18

R. F. NEWBOLD

comment on whether the breast is covered and if so by what and for what purpose is another means of focusing attention upon it. Examples involving Beroe, Chalcomede, and a nameless Bacchant (30.217) have already been noted. Further examples include Deceit telling Hera to put a leather girdle about her breast to enhance her power to charm. It allegedly puts to shame the girdle of Aphrodite (8.169-175). When the androgynous Dionysus disguises himself as a woman to deceive Hera, he puts a band around the projecting circle of his breast (14.164-165). A Hamadryad modestly covered the circle of her breast with a green girdle (2.110-111). Having been spied bathing by Actaeon, Artemis covered her chaste (cTo,(ppovcC;) breasts with a maidenly girdle (5.313). A red band circled the rounded curve of Pallene's non-drooping breasts (48.115). The just-deflowered and awake Aura put her bodice back on again and also tightened her girdle around her breast (48.658-660). Each daughter of Lamos wore a yellow xvr6v about her bosom (9.4748). Mystis first had the idea of covering the naked breast with bronze plates (9.125-126). Bacchants wore animal skins over their breasts."8 Winter wears a bodice of snow on her frost-covered br.east (11.493-494). References to uncovering the breast (apart from mourning purposes, see below) include Aphrodite taking a girdle from her bosom and giving it to Hera (32.2-3); Zeus loosening the bodice around Europa's breast (1.346-347) and Dionysus doing likewise in his rape of Aura (48.654-655); and Persephone loosening the chaste bodice that exerted pressure on her breast (5.605). Because Clymene bathed without a bodice, "the glowing circle of her round silvery breasts illuminated the stream" (38.127-129). With so much focus on breasts, and authorial appraisal of them by frequent application of epithets, it is not surprising that comparison and competitiveness should occasionally occur and go beyond Semele rating Rheia's breasts as a superior source of nurturance, to physical comparison. There is an almost phallic competitiveness about the way Aura exalts her masculine breasts over Artemis', fondling and then labeling the latter's as full, soft, and like a married woman's, full of milk. Aura's, by contrast, she says, are round, unripe, and declare her virginity.19 Such critical appraisal was to prove fatal to the utterer. In asking for help from Nemesis in punishing Aura, Artemis is at first too ashamed to tell how her breasts were mocked by Aura (48.423-424). Later, when Aura has become pregnant, Artemis cannot help retorting that Aura's breasts have lost their masculine shape and become swollen with milk (48.763-764). Aura's maternal feminization becomes complete when she is turned into a fountain and her breasts jet forth water forever (48.936-937).

18

14.357-358,

19 48.351-353,

see R. Schmiel,

28.24, and cf. the corrupt passage at 47.9-10. 364-369. On the several masculine characteristics of Aura, "The Story of Aura," Hermes 121 (1993) 470-83.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

19

4. Baring the breast in grief Most references to bared breasts and garments torn therefrom are so that the breasts can be beaten, reddened, and scored in order to demonstrate grief, as does Autonoe at the rumor of her son Actaeon's death (5.377-379); as do Indian women at the death of their menfolk (24.184-186); mourners in the palace of the late Staphylus (18.331-332); the servants of Ino (9.296); and Erigone at the death of her father (47.189). On other occasions it is simply the baring of the breast in grief that is reported.20 5. Spontaneous flows of milk. Some of the breastfeeding examples cited in categories la and lb include reference to milk flowing freely and spontaneously. Before accepting Dionysus, Ino was holding her son in her arms and "her swelling breasts dropt the dew of swelling (Okt3otepvoto, better 'compressed') milk" (9.57-58). Milk flowed spontaneously from the breasts of Bacchants as they suckled lion cubs (24.131). The milk of Hera that flowed so abundantly for Dionysus gave rise to the Milky Way (35.308-311). In addition, there are kinds of spontaneous flows, for example from the earth, that are, or are approximate to, personifications of the source.2' In the great scene of Bacchic revelry at the beginning of book 22, included amongst the miracles is a fountain of water that turns white and gushes forth milk so that Naiads could bathe in and drink it (22.16-19). A rock spewed forth wine from a red breast. The wine poured down a hill in sweetto-drink streams and honey trickled from spontaneously flowing hollows/breasts (x6Xirov) in the ground (22.19-24). In another scenic description, the landscape around Beroe/Beirut included a stream of milk, and in a sandy bay (ic6kXip) "the foamy stone teemed with sweetsmelling wine and brought forth (tAKE) purple fruit on its rocky bosom" (,u5x4, 41.121-125). Remarkable here is the way lactation and parturition imagery have been blended. A breast-hill (KokXvfl) is struck by Dionysus so that wine pours from it (48.574577). A similar effect is achieved by a Bacchant, but streams of milk as well as wine poured forth.22

9.253 (Ino), 30.164 (Eerie), 46.279 (Agave). As are the commonly occurring phrases "bosom of the earth" (x6k6io; apo-pln; or Xo6vio;, 1O times), "of the sea" (OaXacta-cto; or LX6; 7 times), "of the sky" (aiOkpio;, 3 times). 22 If the speculations of W. Niederland, "River Symbolism," 45.306-10. Psychoanalvtic Quarterly 25 (1956) 469-504, and 26 (1957) 50-75, that the association of breasts with rivers and seas owes something to unconscious recollections of birth and the flows of liquid that accompany it, are justified, the conjunction of these items in some of Nonnus' scenes (5.605-607, 7.255-264, 23.204-205, 39.108-129, 41.113, 48.306-307) may be a further mark of the deep regression that characterizcs much of his imagery.

20 21

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20

R. F. NEWBOLD

6. Milk versus wine. There are some negative statements about breasts, milk, oral needs, and the ties between mother and child that fill out the constellation of mammary concerns in Nonnus and elaborate some of the categories already discussed. They may indicate the "bad," frustrating mother and breast. Wine cannot replace milk as an infant food, but it can offer an alternative source of oral satisfaction to adults and lay down another marker of independence from the produce of the breast.23 In Nonnus' case the fantasy of not only the wine press but also mother earth providing wine may suggest a certain ambivalence about the power of milk as well as reluctance to be entirely independent of the all-providing breast. The whiteness of milk might be a standard of perfection (4.142, 11.377), but in making the case for wine Dionysus declares: "Forget your wish for your old-fashioned milk: the snowy-white drops pressed from the udders of goats that have just kidded do not make men happy or drive their cares away" (17.78-80). And so Staphylus now drank wine instead of milk (18.212-213). When Erigone went to milk her goats Dionysus stopped her and handed to her father, Icarius, "skins full of curetrouble liquor" (47.40-42), with the recommendation that it is wine that best heals human pain (47.55). Guests of Icarius warmly praise the new beverage, so healing and heavenly to taste, and which, unlike milk, does not spoil and lose its taste (47.78-103). Pan regrets that milk cannot aid the sort of conquest that wine enabled Dionysus to achieve over Nicaea (16.321-338). 7. Failures to nurse. Although Nonnus' world is generally one of oral abundance and availability, there are some exceptions. Women do not always want to suckle infants. Artemis mockingly reminds Aura that she, Artemis, has not nursed a son at her breast (48.862) and asks how an unmarried maiden, Aura, came to have milk in her breast (48.833). No wonder Aura, cruelly deprived of her prized virginity, is reluctant to offer her breast to infants and express what she regards as illegitimate milk (48.906-907). She exposes her twins to wild beasts. Having nursed one, Athene is reported to be unwilling to nurse another Erechtheus (29.336-339). A mad Argive woman killed her son and "never missed him at her nursing breast" (47.491-492), and another threw into the air her infant son "still searching for the welcome milk" (47.188-189). A berserk Nysian woman dragged her baby along the ground and "forgot the breast" (21.113). The leader of the Indians, Deriades, mocking Dionysus, asserts that this time there will be no friendly Nereid or Thetis to receive him at the breast when once again put to flight, a disturbing possibil23 Cf. J. Waddell, "Sucking at the Father's Breast: Oral Magic in AlgonquianEuropean Tradition," Journal of Psychoanalytic Anthropology 6 (1982) 255-76.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

21

ity (27.45-47). And finally, an outside agent can cut breastfeeding short, as when Dionysus tears lion cubs from their mother's milky breasts (9.176). 8. Miscellaneous. The remaining references to breasts and milk (and excluding those that refer to male chests) include examples such as Cadmus expressing milk from the ineffable books (4.267) and Semele sprinkling her breast with sacrificial blood (7.168). Electra laments that she has not had the chance to dandle at her breast the son of her sister (3.338-340). There are two references to the breast of a girl who weaves (10.411-412, 37.631). Wounds to the breast actually occur or are envisaged.24 The above categories and their contents convey a sense of the multi-faceted and significant role played by breasts and milk in the Dionysiaca.25 As we have seen, breasts are suckled, lauded, covered by garments, exposed, ogled, pressed, fondled, sprinkled, derided, beaten, bitten, and wounded, all passive experiences. More actively, they nourish, comfort, heal, confer special status, arouse apprehension and erotic interest, swell and stretch clothing. More actively still, they pour or shoot forth milk, wine, light, lightning, fire, serpents, and arrows of love. They contain energy under pressure (OXtPO'6evo;) so that the contents tend to erupt (6ic6v'rti) just as do the contents of the swelling womb. (Birth by explosive expulsion is another infantile fantasy.) Biochemically, the same neurohormone, oxytocin, targets both breast and uterus, inducing lactation and birth. In Nonnus, swelling wombs and swelling breasts equally convey and contain suppressed or hidden life that can be ejaculated and spurted forth.26 Whether through intuition or residual

Actual: 17.218, 363, 30.225, 36.45. Envisaged: 2.105, 21.9, 48.734. Such an impression is enhanced by simply listing all the adjectives applied to [saC6q. Most refer to function or appearance: unwonted, accustomed, non-drooping (4 times), projecting, horizontal (3), firm, unpressed, ironclad, fat, of a mountain, illegitimate (2), of a goat, human, better, masculine (7), having just flowed, self-flowing, neighboring, milky (2), abundantly milky, newly yielding milk (2), naked, uncovered, hairy, unfeminine, feminine, wet, on the right side, double, twin, red (3), rosy (5), silvery, snowy, fragrant, unripe (3), delicate, swollen (2), god-nourishing (2), child-nourishing (3), father-nourishing, child-rearing, life-bearing. But some personify the breast: evil-averting, helping, wily, prudent, wise, crafty, jealous. A common phrase is .taC6; in the genitive, dependent on a noun emphasising the roundness of the breasts, such as iTV5uand &vtvo. Epithets descriptive of the breast are transferred to the noun, so that we have the bloody, white, swelling, firm, life-giving circle of the breasts. K6klEoq has some adjectives found with taC6q but also all-mothering, compassionate, unharmed, sea-weedy (2), and unsullied. 26 Breasts: 9.57-58, 41.141. Wombs: 8.7, 26.273, 35.39. Cronos' pregnant gullet: 12.51, 25.561, 41.7. Zeus' pregnant head and thigh: 1.10, 7.12. There is also the earth, impregnated by Zeus' sperm, shooting forth a weird, horned progeny, 14.202, and the metaphorically pregnant cloud, 2.481-492. Cf. Winkler (above, n.3) 99-110.

24 25

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22

R. F. NEWBOLD

infantile confusion, parturition and lactation become metaphors and analogues of each other. Both processes exhibit irregularities. Lactation irregularities have already been noted. Parturition irregularities include Zeus giving birth to Dionysus and Athene (1.1-10, 7.7881); male urine, sperm, or castrated genitals mixing with oxhide, earth, or water to produce Orion, Erechtheus, centaurs, Gamos, and Aphrodite;27 parthenogenesis by Hera, Medusa, and Beroe to produce Hephaestus, Pegasus, and Eros (9.229, 31.19-23, 41.129-137); and numerous instances of parthenogenesis by the earth.28 While females demonstrate an awesome capacity to be self-sufficient and create life on their own, males can by pass normal procreative practice at times, fertilize fields other than women's bodies and give birth themselves. Indeed, Zeus' incubation and delivery of Dionysus appears to be one of the greatest feats in Nonnus' epic.29 Similarly, it is the female power to nurture life with their breasts that males appear to both fear and envy. One of the characteristics of primary process thought is less sharp gender differentiation and more androgyny. This level of cognition tends to blend things rather than to separate them, and the fantasy of one gender having the capabilities of the other is easily accommodated. Extending the breast's powers beyond the maternal woman may, intentionally or otherwise, reduce breast envy. The dominant metaphor of the female body in the Dionysiaca is the earth with its fruitful gulfs (iokXoo) and hills (ga5oi).3` Women may at times embody a standard of weakness that it is disgraceful for men to sink to, but they are also portrayed as self-sufficient, powerful, full, rich, and often fearsome containers and sustainers of life, with a capacity to wound and make war, like a lioness.3'

5.611-615, 12.47, 13.99-103, 177-179, 32.71-72, 40.402-406. 13.155,199, 14.25-26, 18.218-221, 25.489-490, 29.261-262, 31.1923, 41.51-66, 48.9, 12-14. Also, a pine tree produces the human race, 12.55-58, and when the earth is sown with dragons' teeth or stone tablets, The human race took some time giants spring up, 4.425-427, 45.170-174. to grasp the necessary male role in procreation. See K. Wilber, Up from Eden (London 1981) 123-25. 29 On the issue of male and female procreation in Nonnus, see R. Newbold, "Some Problems of Creativity in Nonnus' DionYsiaca," Classical AntiquitY 12 (1993) 89-110, esp. 103-5. 1" Rejecting as phallocentric the psychoanalytic view that the Greeks thought of women as symbolically castrated males, P. Du Bois, Sowing the Body: Psvchoanalysis and Ancient Representations of Women (Chicago 1988), argues that in the classical period they used as metaphors of the female body fields, furrows, stones, ovens, tablets, a progression from autonomy to passivity. The first of these metaphors is closest to Nonnus' position. Du Bois. 91, says of snaky-haired Medusa that "this image of the mother who is parthenogenetic, like the earth, or who is androgynous, equipped with a snake/phallus . . . is omnipotent, adequate in herself, not needing the male." The latter alternative recalls the phallic Bacchants of category Id, above. "1 Cf. the lion-nourishing Great Mother figure of Rheia, 9.147, whose chariot is pulled by lions, 15.386. The huntress Nicaea is strongly associated with lions, 15.184-189, 194-203, 16.96-97. They pull her chariot too. A

21

'

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BREASTS AND MILK IN NONNUS' DIONYSIACA

23

To conclude: in many ways the Dionysiaca is a phallic poem, concerned with competition, exhibitionism, boasting, mockery, and concern for gender differentiation.32 But much more so is it an oral poem, where the infantilism of the fantasy life centers not just on endless opportunities for imbibing, whether wine, milk, honey, nectar, or ambrosia, but also on expulsion33 and on images of the female that characterize the oral stage of development, when the self is not well distinguished from the mother and the breast, and when the circle of the breast (see n.27) is not distinguished from the larger circle of the mother, or men from women. Women, microcosmically, and the earth, macrocosmically, are experienced ambivalently as all-nurturant and highly fertile but also potentially dangerous. There is a keen sense of a fall from an oral paradise. The generativity and life-sustainment of the earth, and of the wombs and breasts of women, are enviable sources of power in a world of fantasy where residues of infantile confusion and ignorance about the "facts of life" and just how males and females differ are evident.34 University of Adelaide CW94.1 (2000) R. F. NEWBOLD rnewbold @arts.adelaide.edu.au

Bacchant rides a lion into battle, 43.314, and another is said to have the heart of a lioness, 32.253-254. Bacchants can terrify a lioness to abandon her newly born cubs, 45.304-305. So can Aura, who hunts lionesses and is called an invincible lioness, 48.252, 283, 736-740. 12 So that to be called "womanly" or to be defeated by a woman is a source of great shame. Even flowers, lyre sounds, palm trees, and rocks are assigned different genders. See L. Lind, "Un-Hellenic Elements in the Dionvsiaca," LAC 7 (1938) 57-65, at 62. The mouth is very much a two-way passage. The expulsive faculty is 3 shared by other body sites. Just as lustful Zeus and Hephaestus spurt foam from their penises, so crazed Athamas and Dionysus spurt foam from their mouths, 5.613, 13.179, 10.20, 32.150, 35.272. The unconscious equation of the various organs and their functions can lead, for example, to ideas of giving birth through the mouth. Cronos both swallows and disgorges offspring, 25.560-562, 41.68-76: cf. 21.254-255. For an indication of the relationship between oral and vaginal incorporation, and the multiple interactions of sex, food, and speech, see G. Sissa, "Maidenhood without Maidenhead: The Female Body in Ancient Greece," in D. Halperin, ed., Before Sexuality (Princeton 1990) 339-64, esp. 360. Dilution of gender differences is exemplified by the militant Bacchants and by Dionysus, who disguises himself as a woman, 14.159-167, and who is taunted with effeminacy by Nicaea, Lycurgus, Orontes, Deriades, and Pentheus. On the other hand, Aura could scarcely be more masculine. 14 The threat posed by maternal figures to individuation is expressed by, amongst other images, those of devouring monsters and choking, engulfing serpents. Since sinking and merging into the breast blurs individuality, even the breast can be experienced as devourer. See S. Klein, "Woman as Serpent," in J. Law, ed., Religious Reflections on the Human Bodv (Bloomington 1995) 10036. The theme is also illustrated by R. Newbold, "Discipline, Bondage, and the Serpent in Nonnus' Dionysiaca," CW 78 (1984) 89-98. My thanks to the CW referee for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Sun, 12 May 2013 16:58:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- 2013 Church Business PlanDocument72 pages2013 Church Business PlanNenad MarjanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Deliverance From Destructive CovenantDocument9 pagesDeliverance From Destructive Covenantteddy100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Crypt of Cthulhu 105 v19n03 2000Document40 pagesCrypt of Cthulhu 105 v19n03 2000NushTheEternal100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Introduction To Teaching Qur'AanDocument148 pagesIntroduction To Teaching Qur'AanJawedsIslamicLibrary0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- TainosDocument37 pagesTainosAnthonio MaraghPas encore d'évaluation

- ParacelsusDocument420 pagesParacelsusmassimo100% (12)

- Introduction To Islamic Family LawDocument53 pagesIntroduction To Islamic Family LawRifatPas encore d'évaluation

- OPENQUEST Catching The Wyrm (2022)Document28 pagesOPENQUEST Catching The Wyrm (2022)Pan WojtekPas encore d'évaluation

- Describing PeopleDocument2 pagesDescribing Peoplescatach50% (2)

- Modal VerbsDocument36 pagesModal VerbsZeinab Al-waliPas encore d'évaluation

- FMT and MassageDocument14 pagesFMT and MassageJalabia money100% (2)

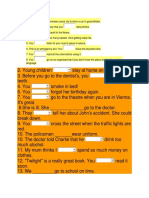

- ENG Sentence Tranformation - If ClausesDocument2 pagesENG Sentence Tranformation - If ClausesMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Akun Pembelajaran Peserta Didik 20519220Document41 pagesAkun Pembelajaran Peserta Didik 20519220DhimzyPas encore d'évaluation

- Elementary Present Continuous and Present Simple ExercisesDocument5 pagesElementary Present Continuous and Present Simple ExercisesKaterina Studentsova100% (1)

- MWS 130S, MWS 140S MWS 330B, MWS 330S, MWS 340B, MWS 430S: Welcome To The Family. Let's Get StartedDocument56 pagesMWS 130S, MWS 140S MWS 330B, MWS 330S, MWS 340B, MWS 430S: Welcome To The Family. Let's Get StartedMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Present Perfect Simple PastDocument1 pagePresent Perfect Simple PastMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Owner's Manual: LP Gas & Charcoal GrillDocument54 pagesOwner's Manual: LP Gas & Charcoal GrillMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- MB20040220 100119Document52 pagesMB20040220 100119Mirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Underwater Archaeological Project at The Ancient City Akra in 2013 (Eastern Crimea)Document12 pagesUnderwater Archaeological Project at The Ancient City Akra in 2013 (Eastern Crimea)Mirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Test Eng. 6Document2 pagesTest Eng. 6Mirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Rules and advice for travel, safety, health and behaviorDocument2 pagesRules and advice for travel, safety, health and behaviorMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Useandcareguide Sve47500b UcDocument51 pagesUseandcareguide Sve47500b UcMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Encore 2550 - Install ManualDocument40 pagesEncore 2550 - Install ManualMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Vezbanja 6 RazredDocument6 pagesVezbanja 6 RazredMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Sava TestDocument2 pagesSava TestMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Cupid and Psyche enDocument7 pagesCupid and Psyche enMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Put The Verbs in Brackets Into The Past Continuous or The Past SimpleDocument2 pagesPut The Verbs in Brackets Into The Past Continuous or The Past SimpleMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Put The Verbs in Brackets Into The Past Continuous or The Past SimpleDocument2 pagesPut The Verbs in Brackets Into The Past Continuous or The Past SimpleMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- GagaDocument1 pageGagaMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Column of Constantine 3. The Valens Aqueduct. 4. The Hippodrome. 5. Walls of Constantinople. 6. Archaeological MuseumDocument12 pagesColumn of Constantine 3. The Valens Aqueduct. 4. The Hippodrome. 5. Walls of Constantinople. 6. Archaeological MuseumMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Vez BanjaDocument3 pagesVez BanjaMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Word FormationDocument15 pagesWord FormationnexkaPas encore d'évaluation

- EnargeiaDocument15 pagesEnargeiaMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Wibiose Conference ProceedingsDocument122 pagesWibiose Conference ProceedingsMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Word Formation - Noun and Adjective Suffixes PDFDocument6 pagesWord Formation - Noun and Adjective Suffixes PDFchronosvitaePas encore d'évaluation

- Cupid and Psyche enDocument7 pagesCupid and Psyche enMirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Verbs Mixed5Document2 pagesVerbs Mixed5Mirjana PrekovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Unlocking The Power of Ishta Devata/ Dharma Devata / Palana Devata/ Kul Devata/guru DevataDocument11 pagesUnlocking The Power of Ishta Devata/ Dharma Devata / Palana Devata/ Kul Devata/guru DevataSangeeta Khanna RastogiPas encore d'évaluation

- (1868) Sketch of The Life and Character of John Lacey: A Brigadier-General in The Revolutionary WarDocument134 pages(1868) Sketch of The Life and Character of John Lacey: A Brigadier-General in The Revolutionary WarHerbert Hillary Booker 2ndPas encore d'évaluation

- Medieval Philosophy SummaryDocument20 pagesMedieval Philosophy SummaryMilagrosa VillasPas encore d'évaluation

- Data Nomor Virtual Account Kelas 1 2019-2020 Pondok Pesantren "Wali Songo" Ngabar Ponorogo PutraDocument9 pagesData Nomor Virtual Account Kelas 1 2019-2020 Pondok Pesantren "Wali Songo" Ngabar Ponorogo PutragagoekPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidayatullah National Law University: Bill of Rights 1689Document16 pagesHidayatullah National Law University: Bill of Rights 1689bhavna khatwaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Word Origins and ClichesDocument86 pagesWord Origins and Clichessharique12kPas encore d'évaluation

- Tibetologie PDFDocument76 pagesTibetologie PDFDanielPunctPas encore d'évaluation

- 2015 - 14 Feb - Soul Sat - Meatfare - HymnsDocument12 pages2015 - 14 Feb - Soul Sat - Meatfare - HymnsMarguerite PaizisPas encore d'évaluation

- Epicenters of JusticeDocument39 pagesEpicenters of JusticeGeorge100% (1)

- 12 PDFDocument15 pages12 PDFYoussef SalimPas encore d'évaluation

- Review Hays The Faith of Jesus Christ PDFDocument10 pagesReview Hays The Faith of Jesus Christ PDFEnrique RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Theology 2Document3 pagesTheology 2Jacky ColsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Sujûd As-Sahw (Corrected)Document4 pagesSujûd As-Sahw (Corrected)DxxnishPas encore d'évaluation

- Confucianism VasariDocument28 pagesConfucianism VasariVince Rupert ChaconPas encore d'évaluation

- History NotesDocument68 pagesHistory NotesnagubPas encore d'évaluation

- MOOT Petitioner Final Draft 2Document32 pagesMOOT Petitioner Final Draft 2Kanishca ChikuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Divine Image ADivine ImageDocument12 pagesThe Divine Image ADivine ImageRani JeePas encore d'évaluation

- Special Puja Guidelines for NavaratriDocument11 pagesSpecial Puja Guidelines for Navaratrisairam_sairamPas encore d'évaluation

- Rekap Peserta Sumpah 2020Document6 pagesRekap Peserta Sumpah 2020Dewi RisnawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Josef Strzygowski - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesJosef Strzygowski - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaWolf MoonPas encore d'évaluation

- Insight into heritage tourism potential of Valapattanam TownDocument25 pagesInsight into heritage tourism potential of Valapattanam TownKIRANDAS NPas encore d'évaluation