Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Peron's Nazi Ties - Foreign and Defense Policy - AEI

Transféré par

cdcrotaerDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Peron's Nazi Ties - Foreign and Defense Policy - AEI

Transféré par

cdcrotaerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Peron's Nazi Ties - Foreign and Defense Policy - AEI

http://www.aei.org/article/foreign-and-defense-policy/regional/latin-am...

Peron's Nazi Ties

Mark Falcoff | Time (Latin American Edition) November 09, 1998

Since the 1930s, the political culture of Argentina has been afflicted by periodic spasms of covert violence, secrecy and denial. As in the case of Vichy France, memory can be an inconvenience or an embarrassment; faced with incidents that require explanation, too many Argentines instinctively reach for the words borron y cuenta nueva (Let's forget it all and start over with a clean slate). As a result, even today nobody knows exactly how many people disappeared during the "dirty war" against subversion (1976-83), nor the number of victims in the left-wing guerrilla violence that preceded it. The 1992 and 1994 bombings of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires and the city's Jewish center, causing the loss of 115 lives, remain unsolved. Even events far more remote have had to wait decades for elucidation. One of the most important of those events is Argentina's vaunted neutrality in World War II, a posture it maintained long after other American republics broke off relations with the Axis. Only since the country's return to democracy in 1983 has the real story of Argentina's covert alignment with the Axis finally begun to emerge. A commission to investigate the activities of Nazism in Argentina, appointed by President Carlos Menem and assisted by an international team of scholars, started work last July. A preliminary report is expected in mid-November, when the scholars meet in Buenos Aires, and a final report a year later. At issue here is not merely a matter of diplomatic taste. Throughout the war, Argentina was regarded by U.S. diplomats and the U.S. media as the regional headquarters for Nazi espionage. After 1945, reports kept cropping up in the U.S. press that Argentina was the final redoubt of important Nazis and their European collaborators, a point dramatically brought home as late as 1960 by the capture and forcible removal to Israeli justice of Adolf Eichmann, principal director of the "final solution." Over the years, these allegations seemed at least superficially credible in light of the emergence in 1946 of Colonel Juan Peron as the leader of a defiant, nationalist Argentina. Though in practice the Peron regime resembled hardly at all the defeated European fascist dictatorships, Peron made no secret of his sympathy for the defeated Axis powers. Argentina's and Peron's apparent preference for the Axis, and particularly for Nazi Germany, has muddied the country's relations with the Anglo-Saxon powers and poisoned its domestic politics. Anti-Peronists have often used the term Nazi (or Pero-Nazi) a bit too freely in attempting to discredit their opponents--not just Peron but also the administration of President Ramon S. Castillo (1940-43), who preceded him. Indeed, Argentina's 1946 elections, the first of three in which Peron was elected to the presidency, were, as much as anything else, a plebiscite on the credibility of such accusations. In recent years, the Canadian scholar Ronald Newton, in his masterly The "Nazi Menace" in Argentina, 1931-47 (Stanford), has suggested that much of the Nazi-fascist menace in Argentina was an invention of British intelligence, fearful of the loss of historic markets in that country to the U.S. after the war, and therefore desirous of straining relations between Buenos Aires and Washington. Far in advance of the final report of President Menem's commission (of which Newton is a member), that theory has now been refuted in an extraordinary piece of investigative reporting--also a major breakthrough in historical scholarship--by Uki Goni, whose Peron and the Germans has just been published in Buenos Aires. In this book the author, who also works as a local correspondent for TIME, establishes that, for all the hyperbole, Washington's darkest suspicions were if anything greatly understated. For one thing, Goni demonstrates that the Castillo administration, and particularly the Argentine Foreign Ministry, was honeycombed with Nazi sympathizers as early as 1942--so much so

1 sur 2

24/08/2013 11:44

Peron's Nazi Ties - Foreign and Defense Policy - AEI

http://www.aei.org/article/foreign-and-defense-policy/regional/latin-am...

that it is difficult to see why any of the most anxious partisans of neutrality, such as found in the secret lodges of the Argentine army, felt the need to overthrow the government at all! For another, Goni establishes without doubt that there was an Argentine-German conspiracy to detach neighboring countries from their sympathetic posture toward the Allied cause. This conspiracy reached its maximum point of success in Bolivia, where a regime friendly to the U.S. was ousted by a military coup in 1943. Argentina was also active (if less successfully) in Brazil, Paraguay and Chile. Goni demonstrates that operatives of Heinrich Himmler's Sicherheitdienst, or SD, the political-espionage service of the Nazi Party, moved without difficulty throughout Argentina for the entire war. In spite of an Argentine parliamentary commission on un-Argentine activities and a special office of the Federal Police deputed to prosecute such agents of espionage, Himmler's operatives were rarely disturbed, and after they were finally jailed at the end of the war, they were released as soon as possible. As late as 1944, the Argentine military thought the Nazis were going to win the war, and during the first months of 1945 tried to act as if they had. Having bet on the wrong horse, Peron and his associates--far from reproaching themselves for their bad judgment, or at least striving to correct it--closed ranks and came to the rescue of some of the most unsavory figures to escape Allied justice in liberated Europe. After 1945, the Argentine consulate in Barcelona became a distribution point for false passports, which enabled literally hundreds if not thousands of Nazi functionaries to escape to Argentina, including the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele. Eventually Argentina provided safe haven for such sinister personalities as Belgian Nazi collaborator Pierre Daye; Reinhard Spitzy, the Austrian representative of Skoda in Spain; Charles Lescat, former Vichy functionary and onetime editor of the scurrilous magazine Je Suis Partout; SS functionary Ludwig Lienhardt; German industrialist Ludwig Freude; SS functionary (for a time) Klaus Barbie, "the Butcher of Lyons"; Eichmann; and Eichmann's adjutant Franz Stangl. Argentina also became home to dozens of Croats, veterans of the bloodthirsty Ustashe, as well as the wartime Prime Minister of occupied Yugoslavia, Milan Stojadinovich. Some of these people had an important afterlife in Peron's Argentina. Vichyite Frenchman Jacques de Mahieu drafted the doctrinal texts of Peron's movement and became an important ideological mentor to Roman Catholic nationalist youth groups in the 1960s. Daye became the editor of one of the official Peronist magazines; Freude's business ventures prospered, and his son Rodolfo was the chief of presidential intelligence during Peron's first presidency. In 1951 Stojadinovich founded one of Argentina's main business dailies, El Economista, which still carries his name on its masthead. Many of these people also benefited from the clandestine assistance of the Vatican in making their escape from Europe to Argentina. The one question Goni's book cannot answer is why either the Catholic Church or the Peron regime felt so strongly about the need to provide succor and assistance to partisans of a lost (and, one would have thought, thoroughly discredited) cause. Money did have something to do with it. Argentine officials in Europe were known to sell passports for large sums. But there appears to have been a vague, confusing and still unexplained overlap between defeated Central European fascism, preconciliar Catholicism and nascent Peronism. A case in point is the career of a Croatian priest based in Rome, the Rev. Krunoslav Draganovic, who was deputed by Peron to facilitate the escape of hundreds of Nazis and their collaborators to South America, including the infamous Barbie. When the Butcher of Lyons asked the clergyman why he was going out of his way to help him, Draganovic merely replied, "We have to maintain a sort of moral reserve on which we can draw in the future." Thus the European fascist sensibility, if not precisely the fascist system, found new roots and new life in the South Atlantic region. Mark Falcoff is resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. His books include Prologue to Peron: Argentina in Depression and War, 1930-43.

2 sur 2

24/08/2013 11:44

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Real Odessa: How Perón Brought the Nazi War Criminals to ArgentinaD'EverandThe Real Odessa: How Perón Brought the Nazi War Criminals to ArgentinaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (17)

- Carlos BarralDocument32 pagesCarlos Barralmanusod1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Newton, The German Argentines Between Nazism and NationalismDocument40 pagesNewton, The German Argentines Between Nazism and NationalismLada LaikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Spanish Holocaust Review RevisedDocument6 pagesSpanish Holocaust Review RevisedSathyaRajan Rajendren0% (1)

- Final Judgment; The Story Of NurembergD'EverandFinal Judgment; The Story Of NurembergÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- American War Correspondents in SpainDocument63 pagesAmerican War Correspondents in SpainEric DoylePas encore d'évaluation

- On the Edge of the Holocaust: The Shoah in Latin American Literature and CultureD'EverandOn the Edge of the Holocaust: The Shoah in Latin American Literature and CulturePas encore d'évaluation

- Henri Pozzi Black Hand Over EuropeDocument81 pagesHenri Pozzi Black Hand Over Europeandrej08100% (6)

- Hitler's Shadow Empire: Nazi Economics and the Spanish Civil WarD'EverandHitler's Shadow Empire: Nazi Economics and the Spanish Civil WarÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- Fighting For Franco International Volunteers in Nationalist Spain During The Spanish Civil War (Judith Keene) (Z-Library)Document321 pagesFighting For Franco International Volunteers in Nationalist Spain During The Spanish Civil War (Judith Keene) (Z-Library)ic0gn1t4xPas encore d'évaluation

- Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945D'EverandEavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939-1945Évaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Comintern and The Spanish Civil War in SpainDocument10 pagesComintern and The Spanish Civil War in Spain강원조100% (1)

- Preston. El Mito de Hendaya.Document17 pagesPreston. El Mito de Hendaya.kopdezPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 EssayDocument26 pages1 EssayChengyu HuPas encore d'évaluation

- The myth of the Jewish menace in world affairs or, The truth about the forged protocols of the elders of ZionD'EverandThe myth of the Jewish menace in world affairs or, The truth about the forged protocols of the elders of ZionÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and CommemorationD'EverandThe Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and CommemorationPas encore d'évaluation

- Nazism, the Holocaust, and the Middle East: Arab and Turkish ResponsesD'EverandNazism, the Holocaust, and the Middle East: Arab and Turkish ResponsesPas encore d'évaluation

- Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold WarD'EverandFugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold WarPas encore d'évaluation

- 51 Documents - Zionist Collaboration With The NazisDocument3 pages51 Documents - Zionist Collaboration With The NazisOscar HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Life & Pontificate of Pope Pius XII: Between History & ControversyD'EverandThe Life & Pontificate of Pope Pius XII: Between History & ControversyPas encore d'évaluation

- Portugal, The Consuls, and The Jewish Refugees, 1938-1941 Avraham MilgramDocument31 pagesPortugal, The Consuls, and The Jewish Refugees, 1938-1941 Avraham MilgramMelissa CarcachePas encore d'évaluation

- A Chance to Fight Hitler: A Canadian Volunteer in the Spanish Civil WarD'EverandA Chance to Fight Hitler: A Canadian Volunteer in the Spanish Civil WarPas encore d'évaluation

- Zionist Collaboration With The NazisDocument3 pagesZionist Collaboration With The NazistarnawtPas encore d'évaluation

- Competing Germanies: Nazi, Antifascist, and Jewish Theater in German Argentina, 1933–1965D'EverandCompeting Germanies: Nazi, Antifascist, and Jewish Theater in German Argentina, 1933–1965Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Lexicon of TerrorDocument3 pagesA Lexicon of TerrorGabriela HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Denying The Holocaust: The West Michael MayDocument5 pagesDenying The Holocaust: The West Michael MayLasha ChakhvadzePas encore d'évaluation

- Season of Infamy: A Diary of War and Occupation, 1939-1945D'EverandSeason of Infamy: A Diary of War and Occupation, 1939-1945Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Nazi Paris: The History of an Occupation, 1940-1944D'EverandNazi Paris: The History of an Occupation, 1940-1944Évaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (5)

- Heroes or Villains?: The True Story of Saving Jews in Occupied France Where There Were Heroes and Villains and Sometimes, You Could Not Tell the DifferenceD'EverandHeroes or Villains?: The True Story of Saving Jews in Occupied France Where There Were Heroes and Villains and Sometimes, You Could Not Tell the DifferencePas encore d'évaluation

- José Antonio Primo de Rivera: The Reality and Myth of a Spanish Fascist LeaderD'EverandJosé Antonio Primo de Rivera: The Reality and Myth of a Spanish Fascist LeaderPas encore d'évaluation

- A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation - Updated EditionD'EverandA Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation - Updated EditionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- Ten Proofs Against Six Million Jews Murdered in 'Holocaust'Document11 pagesTen Proofs Against Six Million Jews Murdered in 'Holocaust'Warriorpoet100% (2)

- Nazi Occultism in Argentina Spectacle SyDocument18 pagesNazi Occultism in Argentina Spectacle Sygladyspereyra8150% (2)

- Webster, Nesta - Germany and EnglandDocument88 pagesWebster, Nesta - Germany and EnglandAndemanPas encore d'évaluation

- Pope Pius XII During The Second World War - Mary Ball MartinezDocument7 pagesPope Pius XII During The Second World War - Mary Ball MartinezAugusto TorchSonPas encore d'évaluation

- General Patton On Communism and The Khazar Jews General Patton's WarningDocument6 pagesGeneral Patton On Communism and The Khazar Jews General Patton's WarningNicolas Marion100% (1)

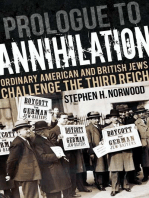

- Prologue to Annihilation: Ordinary American and British Jews Challenge the Third ReichD'EverandPrologue to Annihilation: Ordinary American and British Jews Challenge the Third ReichPas encore d'évaluation

- Historiography Paper Final VersionDocument12 pagesHistoriography Paper Final Versionapi-666652674Pas encore d'évaluation

- Secret Armies The New Technique of Nazi WarfareD'EverandSecret Armies The New Technique of Nazi WarfareÉvaluation : 2 sur 5 étoiles2/5 (1)

- H-Net - Harold Marcuse - Eric Lichtblau' S Book, The Nazis Next Door - How America Became A Safe Haven For Hitler' S Men - 2018-09-11Document3 pagesH-Net - Harold Marcuse - Eric Lichtblau' S Book, The Nazis Next Door - How America Became A Safe Haven For Hitler' S Men - 2018-09-11Adrian TatarPas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiryquestion2 UrsiniDocument4 pagesInquiryquestion2 Ursiniapi-312077969Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Johns Hopkins University Press American Jewish Historical QuarterlyDocument13 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press American Jewish Historical QuarterlyRuaa Al-AwadiPas encore d'évaluation

- Brenneis Holocaust MauthausenDocument38 pagesBrenneis Holocaust MauthausenEliza SmaPas encore d'évaluation

- FileDocument5 pagesFileMáté Bence TóthPas encore d'évaluation

- EU Military Force Intended To Reduce US Influence - GlobalResearchDocument4 pagesEU Military Force Intended To Reduce US Influence - GlobalResearchcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Brazil's Economy - The Deterioration - The EconomistDocument3 pagesBrazil's Economy - The Deterioration - The EconomistcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- EU-Mercosur Trade Talks - Strategic Patience Runs Out - The EconomistDocument3 pagesEU-Mercosur Trade Talks - Strategic Patience Runs Out - The EconomistcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- AI and Life in 2030 PDFDocument52 pagesAI and Life in 2030 PDFjeregonPas encore d'évaluation

- Milrem Robotics THeMIS UGVs Used in A Live-Fire Manned-Unmanned Teaming ExerciseDocument2 pagesMilrem Robotics THeMIS UGVs Used in A Live-Fire Manned-Unmanned Teaming ExercisecdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- ELEBDocument16 pagesELEBcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- General Purpose Bombs MK 80Document1 pageGeneral Purpose Bombs MK 80cdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Memoria Aernnova 11Document39 pagesMemoria Aernnova 11cdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Carta Comaf EngDocument8 pagesCarta Comaf EngcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Ema 40 BD BR: 70mm Air To Ground RocketDocument1 pageEma 40 BD BR: 70mm Air To Ground RocketcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Pratice Bomb BEX 11Document1 pagePratice Bomb BEX 11cdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Skws 022007Document8 pagesSkws 022007cdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- 4868 PBL Pylon Screen TYERMADocument2 pages4868 PBL Pylon Screen TYERMAcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogo OnlineDocument22 pagesCatalogo Onlinecdcrotaer100% (2)

- Financial Highlights 2011-2012Document1 pageFinancial Highlights 2011-2012cdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Composites Manufacture and Machining A4 PDFDocument2 pagesComposites Manufacture and Machining A4 PDFcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- AKAERDocument1 pageAKAERcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Pods Conformal Sensor Installations A4 PDFDocument2 pagesPods Conformal Sensor Installations A4 PDFcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Complex Aircraft Components Machining A4 PDFDocument2 pagesComplex Aircraft Components Machining A4 PDFcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- EQUIPAERDocument1 pageEQUIPAERcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Complex Aircraft Assemblies A4 PDFDocument2 pagesComplex Aircraft Assemblies A4 PDFcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- ÁKAERDocument45 pagesÁKAERcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- PUBCEXBrasil IDocument113 pagesPUBCEXBrasil IcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Development Prospects and Challenges For Brazil - BNDESDocument13 pagesDevelopment Prospects and Challenges For Brazil - BNDEScdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Pube Strange Iron o Brasil IDocument95 pagesPube Strange Iron o Brasil IcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Pub Guia Legal IDocument309 pagesPub Guia Legal IcdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation

- Exp brz-2501465Document86 pagesExp brz-2501465Lee GordonPas encore d'évaluation

- Économie Brésilienne - MantegaDocument25 pagesÉconomie Brésilienne - MantegacdcrotaerPas encore d'évaluation