Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Quality in Education

Transféré par

Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKATitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Quality in Education

Transféré par

Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKADroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Introduction: In all aspects of the school and its surrounding education community, the rights of the whole child,

and all children, to survival, protection, development and participation are at the centre. This means that the focus is on learning which strengthens the capacities of children to act progressively on their own behalf through the acquisition of relevant knowledge, useful skills and appropriate attitudes; and which creates for children, and helps them create for themselves and others, places of safety, security and healthy interaction. (Bernard, 1999) Quality Education Includes: Learners who are supported in learning by their families and communities, and are healthy, well-nourished and ready to participate and learn; Processes through which trained teachers use child-centred teaching approaches in well-managed classrooms and schools and skilful assessment to facilitate learning and reduce disparities. Environments that are healthy, safe, protective and gender-sensitive, and provide adequate resources and facilities; Content that is reflected in relevant curricula and materials for the acquisition of basic skills, especially in the areas of literacy, numeracy and skills for life, and knowledge in such areas as gender, health, nutrition, HIV/AIDS prevention and peace. Outcomes that encompass knowledge, skills and attitudes, and are linked to national goals for education and positive participation in society. This definition allows for an understanding of education as a complex system embedded in a political, cultural and economic context. Quality in Education: School systems work with the children who come into them. The quality of childrens lives before beginning formal education greatly influences the kind of learners they can be. There are many factors affecting quality in education, including health, early childhood experiences and home support. Education provides individual children with the knowledge and skills necessary to advance themselves and their nation economically. Socioeconomic factors, such as family income level, parents' level of education, race and gender, all influence the quality and availability of education as well as the ability of education to improve life circumstances.

Education is the process in which knowledge, skills and set of values are passed or imparted from a person to another. In the formal setting wherein learning is done in schools, the success of educators in imparting knowledge and skills depends on the quality of education they are providing to their students.

Generally, children who are fortunate in being born to educated parents or having caring, competent teachers do very well, and are able to find jobs demanding high productivity. However, the average is appallingly low. The results are low productivity, poor skills, and massive unemployment even after several years of schooling, or even college education. Various studies have shown that children coming from a deprived background do not have a supportive learning environment and feel alienated in schools. The government school teachers, even motivated ones, find it difficult to address their special needs. Therefore, increasingly it is being realized that only by improving the quality of education can the positive effects of growing enrolments be sustained. A childs exposure to curriculum his or her opportunity to learn significantly influences achievement, and exposure to curriculum comes from being in school (Fuller et al., 1999).

Good health and nutrition: Physically and psychosocially healthy children learn well. Healthy development in early childhood, especially during the first three years of life, plays an important role in providing the basis for a healthy life and a successful formal school experience (McCain & Mustard, 1999). Adequate nutrition is critical for normal brain development in the early years, and early detection and intervention for disabilities can give children the best chances for healthy development. Prevention of infection, disease and injury prior to school enrolment are also critical to the early development of a quality learner.

Family support for learning: Parents may not always have the tools and background to support their childrens cognitive and psychosocial development throughout their school years. Parents level of education, for example, has a multifaceted impact on childrens ability to learn in school. Parents' education level directly correlates to the importance and influence of education in their children's lives. Parents with little formal education may also be less familiar with the language used in the school, limiting their ability to support learning and participate in school-related activities. Educated parents can assess a son or daughter's academic strengths and weaknesses to help

that child improve overall academic performance. The educated parent also sets expectations of academic performance that propel students forward in their achievement levels. However, even if educated, parents who struggled academically and do not think highly of formalized education may have negative attitudes toward education that can still hinder the child academically.

Quality learning environment: Learning can occur anywhere, but the positive learning outcomes generally sought by educational systems happen in quality learning environments. Learning environments are made up of physical, psychosocial and service delivery elements. Physical learning environments or the places, in which formal learning occurs, range from relatively modern and well-equipped buildings to open-air gathering places. The quality of school facilities seems to have an indirect effect on learning, an effect that is hard to measure. Schools include but are not limited to primary schools, secondary schools, sixth form schools, vocational schools, colleges and universities. But for these educational institutions to function well so as to expedite the learning process, educational facilities are a necessity. These facilities refer to all the structures as well as equipment used to facilitate learning in schools. These facilities include buildings, classrooms, conference hall, libraries, gymnasiums, and other structures and equipment. Without these facilities, students have to endure holding classes under the scorching heat of the sun or risk getting wet by torrents of rain. Without these facilities, students would not have a decent place to learn the knowledge and skills they need. Many young people around the world especially the disadvantaged are leaving school without the skills they need to thrive in society and find decent jobs. As well as thwarting young peoples hopes, these education failures are jeopardizing equitable economic growth and social cohesion, and preventing many countries from reaping the potential benefits of their growing youth populations. The 2012 Education for All Global Monitoring Report examines how skills development programmes can be improved to boost young peoples opportunities for decent jobs and better lives.

Quality in Higher Education: A number of environmental forces are driving change within and across countries and their higher education. Higher education environments across the globe are frequently described as turbulent and dynamic. Both global and national forces are driving change within and across individual countries and their higher education institutions. These changes have served to put the issue of quality management firmly on the agendas of national governments, institutions, academic departments and individual programmes of study. Despite the progress that has been made through research and debate, there is still no universal consensus on how best to manage quality within Higher Education. One of the key reasons for this is the recognition that quality is a complex and multi-faceted construct, particularly in Higher Education environments (Harvey and Knight, 1996; Cheng and Tam, 1997; Becket and Brookes, 2006). As a result, the measurement and management of quality has created a number of challenges.

Poor Allocation of Funds: The need for increased expenditure on education has been talked about since the late sixties. Anil Sadgopalvi, Professor of Education, University of Delhi, says the allocation for education as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been steadily declining since the promulgation of the New Economic Policy. This investment has continued to decline during the United Progressive Alliance rule as well in spite of the levy of the 2 per cent Education Cess and a substantial portion of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) funds coming from international agencies. The present level of investment is as low as the level achieved 20 years ago 3.5 per cent of the GDP. The political will to mobilise adequate public resources for education has reached a low-ebb.

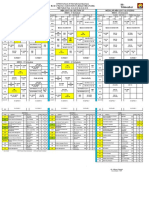

Statistics of literacy rate according to various states in India: Kerala is the most literate state in India, with almost 100% literacy, followed by Mizoram at 92.6%. Bihar is the least literate state in India. Though the literacy rate of Bihar is not up to the mark but the state shows a great improvement from 2001 to 2011 as the increase of literacy rate is highest in Bihar in the respect to others. Table 1 shows the statistics of literacy rate according to Census 2001, Provisional report of Census 2011 and NFHS 3 (National Family and Health Survey) reports and the present increase of literacy rate from 2001 to 2011 also reflects in this table.

Rank State

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Kerala Mizoram Tripura Goa Himachal Pradesh Nagaland Sikkim Tamil Nadu Maharashtra Manipur Uttarakhand Gujarat West Bengal Punjab Haryana Karnataka Meghalaya Odisha Assam Chattisgarh Madhya Pradesh Uttar Pradesh Jammu and Kashmir Andhra Pradesh Jharkhand Rajasthan Arunachal Pradesh Bihar India

Literacy rate (%) NFHS 3 100 75.9 74.2 83.3 100 77.6 73.6 74.2 63.7 60.9 73.7 74.1 71.6 74 71.4 69.3 72.1 68.8 70.3 63.6 70.5 61.6 66.7 72.5 58.6 68 62.8 75.82 67.6

Literacy rate (%) 2001 Census 92.19 88.8 73.19 87.4 76.48 76.88 68.81 73.45 66.59 63.74 71.62 69.14 68.84 69.65 67.91 66.64 62.56 55.08 63.25 64.66 60.53 56.27 55.52 60.47 53.56 60.41 54.34 47 64.84

Literacy rate (%) 2011 Census 93.9 91.6 87.8 87.4 83.8 82.9 82.2 80.3 80.1 79.8 79.6 79.3 77.1 76.7 76.6 75.6 75.5 73.45 73.2 71 70.6 71.7 68.7 67.7 67.6 67.1 67 63.8 74.04

Increase (%) 1.71 2.80 14.61 0.00 7.32 6.02 13.39 6.85 13.52 16.06 7.98 10.16 8.46 7.05 8.69 8.96 12.94 10.42 9.95 6.34 10.07 13.43 13.18 7.23 14.04 6.69 12.066 16.8 9.2%

Table 1: Ranking of Indian states according to literacy rate published in the provisional report of Census 2011.

Figure 1. The diagram showing an overview of literacy rate in India

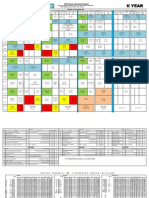

Crude literacy rate in India during 1901 to 2011: In censuses before 1991, children below the age 5 were treated as illiterates. But now the rule is changed to any one above age 7 who can read and write in any language with an ability to understand was considered a literate. The literacy rate taking the entire population into account is termed as "crude literacy rate" , and taking the population from age 7 and above into account is termed as "effective literacy rate". Effective literacy rate increased to a total of 74.04% with 82.14% of the males and 65.46% of the females being literate.

Census Year 1901 1911 1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011

Total (%) 5.35 5.92 7.16 9.50 16.10 16.67 24.02 29.45 36.23 42.84 64.83 74.04

Male (%) 9.83 10.56 12.21 15.59 24.90 24.95 34.4 39.45 46.89 52.74 75.26 82.14

Female (%) 0.60 1.05 1.81 2.93 7.30 9.45 12.95 18.69 24.82 32.17 53.67 65.46

Table 2. The table lists the "crude literacy rate" in India from 1901 to 2011

Figure 2. The diagram showing the uprising percentage of literacy rate from 1901 to 2011

Comparative study of literacy statistics: The table below shows the adult and youth literacy rates for India and some neighbouring countries in 2002. This shows that India is low enough in both adult and youth literacy rate from the neighbouring countries like China and Sri Lanka. Adult literacy rate is based on the 15+ years age group, while Youth literacy rate is for the 1524 years age group (i.e. youth is a subset of adults).

Country China Sri Lanka Burma Iran World Average India Nepal Pakistan Bangladesh

Adult Literacy Rate 95.9% (2009) 90.8 (2007) 89.9% (2007) 82.4% (2007) 84% (1998) 74.04% (2011) 56.5% (2007) 62.2% (2007) 53.5% (2007)

Youth Literacy Rate 99.4% (2009) 98.0 94.4% (2004) 95% (2002) 88% (2001) 82% (2001) 62.7% 73.9% (2010) 74%

Table 3. Comparative literacy statistics

References: 1. Census India. "Census Of India". Retrieved 2011-03-31. 2. Census Of India | url= http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-provresults/indiaatglance.html 3. Census Provional Population Totals. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 2013-02-14. 4. Census report 2001 and 2011 published by Govt. of India. 5. Crossette, Barbara (1998-12-09), "Unicef Study Predicts 16% World Illiteracy Rate Will Increase", New York Times, retrieved 2009-11-27 6. Economic Survey 2004-05, Economic Division, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, quoting UNDP Human Development Report 2004 7. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2009_EN_Complete.pdf 8. National Family Health Survey (NFHS) released NFHS - 3 report on 11 Oct 2007. 9. UNESCO (2004). "Myanmar: Youth literacy rate". Globalis. Retrieved 2009-11-27 10. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Stats.uis.unesco.org. Retrieved 2012-08-14. 11. UNICEF. "At a glance: Myanmar". Retrieved 2009-11-27. 12. UNICEF. "Islamic Republic of Iran Statistics". Retrieved 2009-11-27. 13. World Resources Institute. "Population, Health and Human Well-being: Country Profile of the Islamic Republic of Iran". WRI. Retrieved 2009-11-27. 14. Worldmapper: Youth Literacy. Worldmapper. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Perceived Stress ScaleDocument3 pagesPerceived Stress ScaleSorina NegrilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Life Depends on the Liver: A Guide to Liver HealthDocument4 pagesLife Depends on the Liver: A Guide to Liver HealthDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Life Depends on the Liver: A Guide to Liver HealthDocument4 pagesLife Depends on the Liver: A Guide to Liver HealthDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Table From 02.10.17 To 08.10.17Document4 pagesTime Table From 02.10.17 To 08.10.17Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure - Data Analysis Using SPSSDocument4 pagesBrochure - Data Analysis Using SPSSDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Coursera A5XJSAMU3QM7 PDFDocument1 pageCoursera A5XJSAMU3QM7 PDFDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Mendeley Work:: (Nayal Et Al., 2023) (Baral Et Al., 2023) (Ahmed & Maccarthy, 2022)Document1 pageMendeley Work:: (Nayal Et Al., 2023) (Baral Et Al., 2023) (Ahmed & Maccarthy, 2022)Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Summer Faculty PosterDocument1 pageSummer Faculty Postersaurabh kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- ABDC Journal Quality List 2013Document55 pagesABDC Journal Quality List 2013Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Table From 12.02.18 To 25.02.18Document4 pagesTime Table From 12.02.18 To 25.02.18Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Time Table From 07.08.17 To 20.08.17Document4 pagesTime Table From 07.08.17 To 20.08.17Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Personal quality checklist to improve habitsDocument1 pagePersonal quality checklist to improve habitsDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Coursera A5XJSAMU3QM7 PDFDocument1 pageCoursera A5XJSAMU3QM7 PDFDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- OM Area JournalsDocument4 pagesOM Area JournalsDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- CHV-Books Update (2019-20) International Business Books ListDocument3 pagesCHV-Books Update (2019-20) International Business Books ListDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Git, Gis, Gip, Gsa: Gitam University Academic Calendar For 2015-16Document3 pagesGit, Gis, Gip, Gsa: Gitam University Academic Calendar For 2015-16Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- NCLSCM - 2015 Conference BrochureDocument2 pagesNCLSCM - 2015 Conference BrochureDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- 406 Marketing Logistics (2014-2016) IV Trimester Course OutlineDocument2 pages406 Marketing Logistics (2014-2016) IV Trimester Course OutlineDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- TIME TABLE V (2012-14) TRIMESTER..25.11.13 To 07.12.13Document2 pagesTIME TABLE V (2012-14) TRIMESTER..25.11.13 To 07.12.13Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- I-Trimester Time TableDocument15 pagesI-Trimester Time TableDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- WEEK - I Schedule: GITAM School International BusinessDocument3 pagesWEEK - I Schedule: GITAM School International BusinessDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- 507 (6) Performance Management (2012-14)Document4 pages507 (6) Performance Management (2012-14)Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Entrepreneurial Attitude of Business Management Students-An Empirical InvestigationDocument2 pagesEntrepreneurial Attitude of Business Management Students-An Empirical InvestigationDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- ASCI-Application Format For Asst Librarian-VasubabuDocument3 pagesASCI-Application Format For Asst Librarian-VasubabuDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- WEEK - I Schedule: GITAM School International BusinessDocument3 pagesWEEK - I Schedule: GITAM School International BusinessDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- PHD M.phil Adm Ad 2013 Dec 06Document1 pagePHD M.phil Adm Ad 2013 Dec 06Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- A Study of Emotional Intelligence of The Employees at Workplace in Manufacturing Sector (With Special Reference To Pune District)Document2 pagesA Study of Emotional Intelligence of The Employees at Workplace in Manufacturing Sector (With Special Reference To Pune District)Dr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- PMDocument5 pagesPMDr. VENKATAIAH CHITTIPAKAPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Keyboard ShortcutsDocument5 pagesBest Keyboard Shortcutsapi-258362191Pas encore d'évaluation

- Experimental Research - Research DesignDocument15 pagesExperimental Research - Research Designvanilla_42kpPas encore d'évaluation

- For More Information: WWW - Kimiafarma.co - IdDocument2 pagesFor More Information: WWW - Kimiafarma.co - IdcucuPas encore d'évaluation

- Program Pandu Puteri KloverDocument33 pagesProgram Pandu Puteri KloverCy ArsenalPas encore d'évaluation

- Color Your InterestsDocument2 pagesColor Your InterestsMyrrh Tagurigan Train100% (1)

- 3 Schizophrenia AssessmentDocument36 pages3 Schizophrenia AssessmentArvindhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tensile Load Testing in COMSOLDocument15 pagesTensile Load Testing in COMSOLSyed TaimurPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentacin Intro Distribucin Por Variables A Taste of The MoonDocument8 pagesPresentacin Intro Distribucin Por Variables A Taste of The MoonClemente TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Magazines: Reading ComprehensionDocument8 pages1 Magazines: Reading ComprehensionKetevan KhokhiashviliPas encore d'évaluation

- Sloan - Brochur BBBDocument24 pagesSloan - Brochur BBBarunpdnPas encore d'évaluation

- SelfDocument2 pagesSelfglezamaePas encore d'évaluation

- Effect of Container Size on Candle BurningDocument4 pagesEffect of Container Size on Candle BurningAinul Zarina AzizPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment and Evaluation of Learning Part 3Document3 pagesAssessment and Evaluation of Learning Part 3jayson panaliganPas encore d'évaluation

- George ResumeDocument3 pagesGeorge Resumeapi-287298572Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Issues in Multicultural PopulationsDocument19 pagesEthical Issues in Multicultural Populationsapi-162851533Pas encore d'évaluation

- Are Women Better Leaders Than MenDocument5 pagesAre Women Better Leaders Than MenArijanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Zimbabwe School Examinations Council Physics 9188/4: T-1Ufakose HighDocument6 pagesZimbabwe School Examinations Council Physics 9188/4: T-1Ufakose HighLaura MkandlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Support Vector ClassificationDocument8 pagesSupport Vector Classificationapi-285777244Pas encore d'évaluation

- Genalyn Puno Cordez Resume for IT Administration PositionDocument4 pagesGenalyn Puno Cordez Resume for IT Administration PositionJay Mark Albis SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Multidimensional Locus of Control Attitude Scale Levenson Miller 1976 JPSPDocument10 pagesMultidimensional Locus of Control Attitude Scale Levenson Miller 1976 JPSPAnnaNedelcuPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebook PDF Theories of Personality 9th Edition by Jess Feist PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF Theories of Personality 9th Edition by Jess Feist PDFflossie.thompson26497% (29)

- The Lion Sleeps TonightDocument1 pageThe Lion Sleeps Tonightncguerreiro100% (1)

- Anuja Anil Vichare Resume 5-19-14Document3 pagesAnuja Anil Vichare Resume 5-19-14api-310188038Pas encore d'évaluation

- Improving Criminology Board PerformanceDocument14 pagesImproving Criminology Board PerformanceSharry CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- 1.4 Components of Ethology: InstinctDocument7 pages1.4 Components of Ethology: InstinctAndreea BradPas encore d'évaluation

- Standard Form of Quadratic EquationDocument2 pagesStandard Form of Quadratic EquationTheKnow04Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effectiveness of Modular Learning in Grade 12 HummsDocument28 pagesEffectiveness of Modular Learning in Grade 12 HummsSalvieMaria Adel DelosSantos100% (1)

- Pinto, Ambar Rosales, Omar - ILIN165-2023-Assignment 2 Peer-EditingDocument11 pagesPinto, Ambar Rosales, Omar - ILIN165-2023-Assignment 2 Peer-EditingAmbar AnaisPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Percentage RelationshipsDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Percentage RelationshipsFelmar Morales LamacPas encore d'évaluation

- UNC Charlotte Magazine, 2Q, 2009Document46 pagesUNC Charlotte Magazine, 2Q, 2009unccharlottePas encore d'évaluation

- Cold Calling 26 AugDocument4 pagesCold Calling 26 AugGajveer SinghPas encore d'évaluation