Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Farakka Barrage

Transféré par

rezaaaron0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

348 vues13 pagesBangladesh is a small part of the hydrodynamic system that includes the countries of Bhutan, china, india, and Nepal. Ganges water and sediment have been diverted through a barrage (dam) at Farakka in India. This has adversely affected agriculture, navigation, irrigation, fisheries, forestry, industrial activities, salinity intrusion of coastal rivers.

Description originale:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentBangladesh is a small part of the hydrodynamic system that includes the countries of Bhutan, china, india, and Nepal. Ganges water and sediment have been diverted through a barrage (dam) at Farakka in India. This has adversely affected agriculture, navigation, irrigation, fisheries, forestry, industrial activities, salinity intrusion of coastal rivers.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

348 vues13 pagesFarakka Barrage

Transféré par

rezaaaronBangladesh is a small part of the hydrodynamic system that includes the countries of Bhutan, china, india, and Nepal. Ganges water and sediment have been diverted through a barrage (dam) at Farakka in India. This has adversely affected agriculture, navigation, irrigation, fisheries, forestry, industrial activities, salinity intrusion of coastal rivers.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme DOC, PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

Farakka Barrage: History, Impact and Solution**

M. Khalequzzaman

Department of Geology

University of Delaware

Newark, DE 19716

__________________________________________________________

________

**This article was written in November 1993

Present address: Dept. of Geology & Physics,

Lock Haven University, Lock Haven, PA 17745

Abstract:

Bangladesh is a small part of the hydrodynamic system that

includes the countries of Bhutan, China, India, and Nepal.

Bangladesh lies at the receiving end of this hydrodynamic

system. The Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, of which Bangladesh

is a part, has been created by deposition of river-borne

sediments. Ganges water and sediment have been diverted

through a barrage (dam) at Farakka in India. This has

adversely affected agriculture, navigation, irrigation,

fisheries, forestry, industrial activities, salinity

intrusion of coastal rivers, groundwater, riverbed

aggradation, sediment influx, coastal erosion and

submergence in Bangladesh.

An immediate long term solution to the water sharing

problembetween India and Bangladesh is imperative in order

to mitigate the environmental and economic problems caused

by India's diversion of the Ganges flow. Implementation

of the water rights prescribed by the Helsinki Rule of

1966 can help develop an integrated water resources

management plan for the common rivers of the Indian

subcontinent.

Key words: Bangladesh, Ganges, Farakka, consequences,

solution,

and Helsinki Rule.

Introduction:

Bangladesh lies at the receiving end of the tributaries of

the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers. Ninety percent of the

watershed of both rivers lies outside the territory of

Bangladesh, within the countries of India, Nepal, Bhutan,

and China (Er-rashid, 1978). Adequate flow of these

rivers during the summer months is vital for such basic

functions as irrigation and navigation as well as to

preserve fisheries and other components of Bangladesh's

ecosystem. The Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, of which

Bangladesh is a part, has been created by deposition of

river-borne sediments (Morgan and McIntire, 1959;

Stoddart and John, 1984; Bird and Schwartz, 1987; Singh,

1987a).

A delta can only grow seaward and upward against a rising

sea level when river-borne sediment influx is adequate

(Smith and Abdel-Kader, 1988). Two-thirds of the sediment

supply to Bangladesh is carried by the Ganges and its

tributaries (Holeman, 1968; Milliman and Meade, 1983).

The water and sediment carried by the Ganges is therefore

vital to the existence of the country.

The Farakka Barrage: Impact on Bangladesh:

In 1974 India built a barrage on the Ganges at Farakka in

order to divert water for its own use (Figure 1). The

water is diverted to the Hoogley River via a 26-mile long

feeder canal. During the last 19 years only between 1977

and 1982 has there been an agreement between Bangladesh

and India to address water sharing during the summer

months (Singh, 1987b). The unilateraland disproportionate

diversion of the Ganges since that time has caused a

dangerous reduction in the amount of sediment and water

flow of the Ganges in Bangladesh. Now Bangladesh's delta

receives less sediment and inadequate water flow for

navigation and irrigation during the summer months.

The lack of a workable management plan for water

allocation to Bangladesh has created a situation where

irrigation of crops and navigation are both impossible

during the summer months. The summer of 1993 was

characterized by almost completely dry riverbeds across

the country as reported by all major newspapers in

Bangladesh. Groundwater also dropped below the level of

existing pumping capacity. Such conditions lead to

significant decreases in food production and curtailment

of industrial activities. As a result of a lack of

adequate freshwater inflow, the coastal rivers experienced

saltwater intrusion 100 miles farther inland than normal

during the summer months, affecting drinking water in

these areas (Zaman, 1983).

The reduction in sediment supply to Bangladesh caused by

the dam at Farakka has curtailed delta growth and has led

to increased coastal erosion. At the present time the

rates of nsediment accumulation in the coastal areas are

not sufficient to keep pace with the rate of relative sea

level rise in the Bay of Bengal (Khalequzzaman, 1989).

While the average sedimentation rates range between 4 and

5mm/year, the rate of sea level rise is 7mm/year (Emery

and Aubrey, 1989). In addition, the reduced summer flows

allow sediment to be deposited on the riverbeds

downstream of the dam, resulting in decreased water

carrying capacity during the rainy seasons (Alexander,

1989). This reduction in carrying capacity due to river

bed aggradation has increased the frequency of severe

floods over the last decade, causing enormous property

damage and loss of life. If the amount of sediment influx

in the coastal areas is further reduced by damming the

rivers, then a relative sea level rise in the Bay of

Bengal by 1 meter will severely curtail the delta growth,

resulting submergence of about one-third of Bangladesh

(Broadus and others, 1986; Milliman and others, 1989).

According to the Helsinki Rule signed in 1966 regarding

water rights to international rivers, all basin states of

an international river have the right to access an

equitable and reasonable share of the water flow (Hayton,

1983). There have been many examples of integrated

management plans to address water resources of

international rivers around the world such as

for the Colorado, Rhine, Danube and the Amazon Rivers

(Abbas, 1983; Biswas, 1983). Over the last two decades,

Bangladesh has tried unsuccessfully to come to agreement

with India and the other co-riparian nations on a

acceptable plan for water allocation rights. Since

Bangladesh is a small part of a bigger hydrodynamic system

that comprises several countries in the region, mutual

understanding and cooperation among the co-riparian

countries will be necessary in order to formulate any

long-term and permanent solution to the problem. For

Bangladesh, a developing country, it is important to get

the assistance of the international community, without

whose support the negotiation of a viable agreement

appears impossible and continued loss of human life and

resources is expected in the future.

Solutions:

An immediate long term solution to the environmental and

economic problems caused by India's diversion of the

Ganges flow is imperative. India would prefer to keep the

negotiation of water sharing of the international rivers

bilateral with its neighbors, but to this date there have

over 80 meetings between Bangladesh and India at various

levels which have all been unsuccessful. India prefers to

negotiate water sharing of the international rivers with

its neighbors bilaterally. India has

signed separate treaties, agreements and memorandums with

Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan on water sharing of the

Ganges, Brahmaputra and Indus rivers respectively (Prasad,

1993; Singh, 1987a). Bangladesh would prefer the

involvement of all the co-riparian nations in the

designing of a regional water resources development plan

(Craw, 1981).

The governments of India and Bangladesh have put forward

different schemes to augment water flow in the Ganges

during the summer months. India has suggested the

excavation of a 209-mile link canal (Figure 1) through

which 100,000 cusec (cubic feet per second) of water would

be diverted from the Brahmaputra to the Ganges during the

summer months (Zaman, 1983). The proposed canal would be

about the width of the River Thames of England. Indian

engineers want to build three dams on the Brahmaputra in

Assam to regulate water flow of the river (Craw, 1981).

Bangladesh is reluctant to allow India to build more dams

on the common river for various reasons. Building of the

canal and dams on the Brahmaputra will make Bangladesh

more dependent on India for its share of water. Further

disruption of water flow will be devastating for the

economy of Bangladesh. Diversion of water from the

Brahmaputra will jeopardize irrigation, navigation, and

other components of ecosystem in the Brahmaputra valley.

Besides, about 20,000 acres of lands will be lost in

Bangladesh to the canal. Bangladesh being one of the most

populous countries in the world cannot afford to lose more

land that supports thousands of its people. The concept

of a link canal as proposed by the Indian government is

technically and economically not feasible for Bangladesh

(Zaman, 1983).

If the summer flow of the Ganges has to be augmented by

digging a link canal, then such a canal can be dug within

the territory of Bangladesh. An artificial canal

connecting the Ganges and Barhmaputra between Sirajganj

and Bheramara in Kushtia district would serve the same

purpose for Bangladesh as the 209- mile link canal

proposed by India. The length of the proposed

Sirajganj-Bheramara link canal would only be 60 miles

(Figure 1).

The city of Sirajganj and many other parts of Sirajganj

district are experiencing very high rates of riverbank

erosion (Hossain,1993; Haque, 1989). The diversion of

surplus flow of the Brahmaputra at Sirajganj will help

reduce the water flow velocity. This reduction in flow

velocity would reduce riverbank erosion downstream from

Sirajganj. Comparison between the proposed Indian Link

Canal and the canal proposed by this author is shown in

Table 1 below.

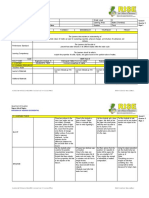

Table 1. Comparison of various parametrs that will have

to be taken into account should the Link Canal proposed by

the Indian Government or by this study has to be

implemented. This parametrs are calculated by this author

based on the available information.

Indian Link Canal Canal Proposed in This Study

Location: Jogigopa Sirajganj-Bheramara

Dimension: 209 mi*0.5 mi*30 ft60 mi*300 ft*20 ft

Volume: 87,398,784,000 ft^3 1,900,800,000 ft^3

Acres lost: 66,880 1454 (1/15 of Indian)

Acres in Bd: 22,293 1454

Discharge: 100,000 cusec 24,000 cusec

Velocity: 1.9 miles/hour 2.72 miles/hour

Distance travelled: 300 miles 60 miles

Brahmaputra flow: 25,000 cusec100,000 cusec in winter

Topography: Against slope Follow natural slope

Relocation: A large number Relatively small number

Navigation: Will be affected Will not be affected in Bd.

Brahmaputra basin env.: Affected Will not be affected

Earth work: 7 Suez Canals 1/6 of the Suez Canal

Sediment load: Will be removed Will stay within Bd. delta

Rivers intercepted: 14 rivers 3 rivers

The Government of Bangladesh proposes to augment the

Ganges flow by building of numerous storage reservoirs in

India, Bhutan, and Nepal to store water during rainy

seasons which can be released in summer months (Figure 1).

This proposal identifies 51 potential reservoir sites

(Craw, 1981; Chowdhury and Khan,1983). The technical and

environmental feasibility study of building reservoirs

have to be carried out before such a proposal can be

accepted for implementation. The potential for electric

power that can be generated from such project is more than

the electricity consumed by North America alone (Prasad,

1993). If Bangladesh's calculations are correct, the

Ganges flow can be augmented by 88,000 to 181,000 cusec

during the summer months. India's calculations show that

only an increase of 50,000 cusec would be possible (Craw,

1981; Chowdhury and Khan, 1983). Since neither India's

nor Bangladesh's proposals are acceptable to each

other, it will be hard to come to a consensus. India,

being the upstream country has yet to show its genuine

desire to solve the water sharing problem between itself

and Bangladesh. There are some alternatives to these two

government proposals.

Without regional cooperation between the co-riparian

nations any major interbasin development activity is

almost impossible (Ahmed et al., 1994). However, a better

physical control of the supply, accumulation, and

dispersal of sediment and water can ensure growth of the

delta. Annual dredging of rivers and

dispersion of the dredged sediments on the flood plains

and delta plains will increase the water carrying capacity

of the rivers, and reduce flooding propensity. The amount

of sediment presently available is still sufficient for

the delta growth if managed correctly. Dredging of the

sediment available on the riverbeds and dispersion of

dredged sediment on adjacent land can augment the delta

growth at a rate that will be enough to keep pace with

sea level rise. Calculations of sediment budget and

accumulation show that 30% of the present suspended

sediment influx of 1.6 billion tons/year in the coastal

areas is capable of aggrading an area of 30,000 sq. km

(the area of all coastal districts of Bangladesh) when sea

level rises at a rate of 1 cm/year. The same amount of

sediment dispersed over a 150,000 sq. km area (greater

than the size of Bangladesh) is capable of aggrading at

a vertical rate of 0.3 cm/year, which would be enough to

keep pace with the present rate of local relative sea

level rise(Khalequzzaman, in press).

Re-excavation and re-occupation of abandoned

distributariesof the major rivers would re-establish the

already disrupted

equilibrium of the hydrodynamic system due to upstream

diversion

of the Ganges. This approach is feasible both

economically and

logistically for Bangladesh. There is a large pool of

available

labor for such an ongoing project. The excavation of dry

channels is already a common practice in rural areas of

Bangladesh.

An integrated management plan for both surface and

groundwater is necessary for Bangladesh to reduce the

economic

hardship that is being caused by the diversion of the

Ganges

(Ahmed et al., 1994). Agriculture, irrigation, navigation,

and

the ecology of the region have all suffered. Many

measures can

be taken within the territory of Bangladesh to mitigate the

economic and environmental degradation that has resulted

from

India's unilateral diversion of the Ganges at Farakka: (a)

conjunctive (surface water-induced groundwater flow) and

planned

seasonal use of groundwater and surface water can enhance

the

supply of water needed for domestic use, irrigation, and

industrial activities (Bredehoeft and Young, 1983); (b)

recycling

of surface water and groundwater can reduce the water

scarcity

during the summer months; (c) forceful injection of

surface water

into the groundwater system during rainy seasons can

reduce the

overflow of rivers and can augment water supply for

irrigation

during the summer months. Such a forceful injection of

fresh

water in the coastal region can help prevent salt water

intrusion

into pumping wells (Brashears, 1946); (d) artificial

recharge of

the aquifers that are located along the major rivers and

their

tributaries in Bangladesh can be enhanced during rainy

seasons by

pumping the groundwater out of those aquifers during summer

months that preceed rainy seasons in Bangladesh (Revelle

and

Laksminarayana, 1975); (e) locating pumping wells along

riverbanks and on the riverbeds during summer months can

increase

the supply of grounwater to the wells. Since most of the

riverbeds are areas of ground water discharge, it will

guarentee

a relatively steady supply of water to the pumping wells

that are

located along the riverbanks; (f) use of sluice gates on

the

tributary rivers and channels during the rainy seasons can

store

water to use for irrigation in summer months; (g)

adaptation of

micro-irrigation can reduce the loss of water though

evaporation

(la Riviere, 1990). Micro-irrigation injects water

directly into

the soil where it is needed the most for the plants; and

(h)

changing the crop pattern can cut down on the need for

excessive

use of irrigation. For example, wheat cultivation

requires much

less water than rice crops.

Due to the decrease in water flow, riverbeds of the

tributaries of the Ganges, along with the main river have

aggradated substantially. Most of the tributaries of the

Ganges

now become dry during the summer months. The sand

deposited on

the riverbeds can be used as construction material to

develop the

infrastructure of the country. The large pool of

available labor

can be used to excavate and transport the sand deposits to

places

where they can be used as construction material for

developing

roads and buildings.

The facts clearly show that for Bangladesh, an agreement is

urgently needed. The international community including

such

organizations as the UNO, UNEP, UNDP, ESCAP, G-7, and

SAARC can

come forward to help solve the water sharing problem

between

Bangladesh and India by mediating negotiations (Abbas,

1983).

International involvement is needed to implement a

management

plan that will protect the water rights of Bangladesh on

the

Ganges and other common rivers prescribed by the Helsinki

Rule of

1966. This issue is of tremendous economic and

humanitarian

concern to Bangladesh.

Conclusions:

The unilateral diversion of the Ganges water by India at

Farakka Barrage has caused a series of adverse

environmental and

ecological problems in Bangladesh. A long-term solution

to water

sharing problems between Bangladesh and India is

imperative.

Without regional cooperation between the co-riparian

nations, any

major interbasin development activity is almost impossible.

However, a better physical control of the supply,

accumulation,

and dispersal of sediment and water can be applied to

mitigate

environmental and ecological degradation resulting from

this

unilateral diversion of the Ganges water. Increased use of

groundwater can reduce the scarcity of water available for

irrigation in Bangladesh as long as it is managed properly.

International involvement can help implement a management

plan

which will protect the water rights of Bangladesh to the

Ganges

and other common rivers prescribed by the Helsinki Rule of

1966.

REFERENCES

Abbas, B.M., 1983, River basin development. In Zaman, M.,

ed.,

River Basin Development: Dublin, Tycooly International

Publishing Ltd., p. 3-9.

Ahmed, Q.A., Verghese, B.G., Iyer, R.R. and Malla, S.K.,

1994.

Converting Water into Wealth - Regional Cooperation in

Harnessing the Eastern Himalayan Rivers: Dhaka, Academic

Publishers, 113 pp.

Alexander, D., 1989. The case of Bangladesh. University

of

Massachusetts, Amherst, 15 p.

Bird, E.F.C., and Schwartz, M.L., 1985. The World's

Coastlines.

New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., p. 761-765.

Biswas, A., 1983, Some major issues in river basin

management for

developing countries. In Zaman, M., ed., River Basin

Development: Dublin, Tycooly International Publishing Ltd.,

p. 18-26.

Brashears, Jr. M.L., 1946, Artificial recharge of

groundwater on

Long Island, New York. Economic Geology, v. 41, p. 503-

516.

Bredehoeft, J.D., and Young, R.A., 1983, Conjunctive use of

groundwater and surface water for irrigated agriculture:

Risk aversion. Water Resources Research, v. 19, no. 5, p.

1111-1121.

Broadus, J., Milliman, J., Edwards, S., Aubrey, D., and

Gable,

F., 1986. Rising Sea Level and Damming of Rivers: Possible

Effects in Egypt and Bangladesh: Proceedings of the

International Conference on the Health and Environmental

Effects of Ozone Modification and Climate Change. Titus,

J., ed., Effects of Change in Stratospheric Ozone and

Global

Climate, v. 4: Sea Level Rise, United Nations Environmental

Program, US EPA, October, 1986.

Chowdhury, G.R., and Khan, T.A., 1983, Developing the

Ganges

Basin. In Zaman, M., ed., River Basin Development: Dublin,

Tycooly International Publishing Ltd., p. 31- 40.

Craw, B., 1981, Why are the Ganges and Brahmaputra

undeveloped?:

politics and stagnation in the rivers of South Asia.

Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, v. 13(4), p. 35-48.

Emery, K.O., Aubrey, D.G., 1989. Tide Gauges of India:

Journal

of Coastal Research, v. 5, no. 3, p. 489-501.

Er-Rashid, H., 1978, Geography of Bangladesh, Dhaka:

University

press, Boulder, Westview Press, 576 pp.

Haque, C.E. and Zaman, M. Q., 1989. Coping with riverbank

erosion

hazards and displacement in Bangladesh: survival strategies

and adjustment. Disasters: 13: 300-314

Hayton, R.D., 1983, The law of international water

resources

system. In Zaman, M., ed., River Basin Development: Dublin,

Tycooly International Publishing Ltd., p. 195-239.

Holeman, J.N., 1968, The sediment yield of major rivers of

the

world. Water Resources Research, v. 4, p. 737-747.

Hossain, M.1993. Economic Effects of riverbank erosion:

some

evidence from Bangladesh. Disasters: 17(1): 25-32.

Khalequzzaman, Md., (in press), Recent floods in

Bangladesh:

possible causes and solutions. Natural Hazards, Kluwer

Publishers, The Netherlands, 16 pp.

Khalequzzaman, Md., 1989. Environmental hazards in the

coastal

areas of Bangladesh: a geologic approach: S. Ferarras and

G. Pararas-Carayannis (eds.), Natural and Man-Made Coastal

Hazards-the proceedings of the 3rd International Conference

on Natural and Man-Made Coastal Hazards, August 14-21,

1988,

Ensenada, Mexico, p. 37-42.

la Riviere, J.W.M., 1990, Threats to the World's Water. In

Managing Planet Earth - Reading from Scientific American:

New York, W.H. Freeman and Company, p. 37-48.

Milliman, J.D., Broadus, J.M., and Gable, F., 1989.

Environmental and economic implications of rising sea level

and subsiding deltas: the Nile and Bengal examples. Ambio,

v. 18(6), p. 340-345.

Milliman, J.D., Meade, R.H., 1983. World-wide delivery of

river

sediment to the oceans. Journal of Geology, v. 91(1):1-21.

Morgan, J.P., and McIntire, W.G., 1959, Quaternary geology

of the

Bengal basin, East Pakistan and India. Bulletin of

Geological Society of America, v. 70, p. 319-342.

Prasad, T., 1993, Developing Indo-Nepal Water Resources.

EOS,

Transect of American Geophysical Union, v. 74(12), p. 131.

Revelle, R. and Laksminarayana, 1975, The Ganges Water

Machine.

Science, v. 188, p. 611-616.

Singh, K., 1987a. India and Bangladesh: Delhi, India,

Anmol

Publications, 187 p.

Singh, I.B., 1987b, Sedimentological history of Quaternary

deposition in Gangetic plain. Indian Journal of Earth

Sciences, v. 14, no. 3-4, p. 272-282.

Smith, S.E., and Abdel-Kader, A., 1988. Coastal erosion

along

the Egyptian delta. Journal of Coastal Research, v. 4, no.

2, p. 245-255.

Stoddart, D.R. and John, S.P., 1984. Environmental

hazards and

coastal reclamation: problems and property in Bangladesh.

In Bayliss, T.P., and Wanmali, S., eds., Understanding the

Green revolutions: London, Cambridge University Press,

p. 339-361

Zaman, M., 1983, The Ganges Basin Development. In Zaman,

M., ed.,

River Basin Development: Dublin, Tycooly International

Publishing Ltd., p. 99-109.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Boroibari, Raumari Day and Today's PerspectiveDocument2 pagesBoroibari, Raumari Day and Today's PerspectiverezaaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- Reunion of Hamas and FatahDocument1 pageReunion of Hamas and FatahrezaaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- Formation of National Identity in Bangladesh and Rabindranath TagoreDocument2 pagesFormation of National Identity in Bangladesh and Rabindranath TagorerezaaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- Making of Laden, Root Cause of Resentment and What NextDocument3 pagesMaking of Laden, Root Cause of Resentment and What NextrezaaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- A History of American WarsDocument5 pagesA History of American WarsrezaaaronPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Red Category Consent & Authorization Orders PDFDocument5 pagesRed Category Consent & Authorization Orders PDFap26n1389Pas encore d'évaluation

- In Memoriam Ivo KolinDocument5 pagesIn Memoriam Ivo KolinTimuçin KarabulutlarPas encore d'évaluation

- Q3 LAW Science 9 WEEKS 5 6Document6 pagesQ3 LAW Science 9 WEEKS 5 6Ace AntonioPas encore d'évaluation

- More Water For Arid Lands PDFDocument164 pagesMore Water For Arid Lands PDFoscardaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Kurinja KeeraiDocument6 pagesKurinja Keeraimmarikar27Pas encore d'évaluation

- Science 4 Week 5 Pivot 4a Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesScience 4 Week 5 Pivot 4a Lesson PlanPia PrenrosePas encore d'évaluation

- Clinoptilolite (Natural Zeolite)Document4 pagesClinoptilolite (Natural Zeolite)Hamed HpPas encore d'évaluation

- CLEXTRAL Preconditioner Plus EN PDFDocument2 pagesCLEXTRAL Preconditioner Plus EN PDFÁrpád OrbánPas encore d'évaluation

- Science COT DLP 4th QuarterDocument5 pagesScience COT DLP 4th QuarterClaudinePas encore d'évaluation

- Tubingal HwsDocument3 pagesTubingal Hwsasebaei95Pas encore d'évaluation

- Problem Chapter 9Document48 pagesProblem Chapter 9Syahid ZamaniPas encore d'évaluation

- PURELAB Chorus Range Brochure LITR40040-04Document16 pagesPURELAB Chorus Range Brochure LITR40040-04Luis Luna CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S0007681316300192 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0007681316300192 Main罗准恩 Loh Chun EnPas encore d'évaluation

- Irrigation Engineering Alwar PDFDocument30 pagesIrrigation Engineering Alwar PDFMahesh MalavPas encore d'évaluation

- Đề Cương Ôn Tập Giữa Kì 2-Anh 8-23-24Document8 pagesĐề Cương Ôn Tập Giữa Kì 2-Anh 8-23-24đâyyy Ngân (Ngân đayyyy)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Technical Guidance Document Quality MonitoringDocument27 pagesTechnical Guidance Document Quality MonitoringtalhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Boilers BasicsDocument19 pagesBoilers BasicsShayan Hasan KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Practice and Minimum Standards For The Welfare of PigsDocument23 pagesCode of Practice and Minimum Standards For The Welfare of Pigskiel macatangayPas encore d'évaluation

- The Life Cycle of Plants MST UnitDocument26 pagesThe Life Cycle of Plants MST UnitNancy CárdenasPas encore d'évaluation

- T155Document4 pagesT155Katerin HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- PDS Poweroil RP DW 100Document2 pagesPDS Poweroil RP DW 100Nitant MahindruPas encore d'évaluation

- Catch Basin Detail: Property LineDocument1 pageCatch Basin Detail: Property LineB R PAUL FORTINPas encore d'évaluation

- Transformer Fire ProtectionDocument43 pagesTransformer Fire ProtectionJairo WilchesPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal Pollution: Victor S. KennedyDocument11 pagesThermal Pollution: Victor S. Kennedy110017 LAURA MARIA RODRIGUEZ TARAZONAPas encore d'évaluation

- VALVITALIA-cat. SAN Desuperheater - Rev1.1Document8 pagesVALVITALIA-cat. SAN Desuperheater - Rev1.1lydia.wasprimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Division of Negros Occidental: The Learners Demonstrate An Understanding ofDocument39 pagesDivision of Negros Occidental: The Learners Demonstrate An Understanding ofRAMIR BECOYPas encore d'évaluation

- GEOGRAPHY Yousuf MEMON Water CHAPTERDocument28 pagesGEOGRAPHY Yousuf MEMON Water CHAPTERHey wasupPas encore d'évaluation

- Design of Canal Distributary With Hydraulic FallDocument19 pagesDesign of Canal Distributary With Hydraulic FallRajeev Ranjan100% (1)

- Models - Heat.potato Drying PDFDocument26 pagesModels - Heat.potato Drying PDFsaleigzer abayPas encore d'évaluation

- OSD UndergroundDocument14 pagesOSD UndergroundMohamad Zahir RazakPas encore d'évaluation